Alfred North Whitehead

by Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

First published Tue May 21, 1996; substantive revision Tue Sep 4, 2018

“There is only one subject matter for education, and that is Life in all its manifestations…You cannot shelter theology from science, or science from theology…we should aim at the integration of science and religion, and turn the impoverishing opposition between the two into an enriching contrast…[If the condition of mutual tolerance is satisfied, then] a clash of doctrines is not a disaster—it is an opportunity…The clash is a sign that there are wider truths and finer perspectives within which a reconciliation of a deeper religion and a more subtle science will be found…our existence is more than a succession of bare facts.”

-- Alfred North Whitehead, by Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) was a British mathematician and philosopher best known for his work in mathematical logic and the philosophy of science. In collaboration with Bertrand Russell, he co-authored the landmark three-volume Principia Mathematica (1910, 1912, 1913). Later, he was instrumental in pioneering the approach to metaphysics now known as process philosophy.

Although there are important continuities throughout his career, Whitehead’s intellectual life is often divided into three main periods. The first corresponds roughly to his time at Cambridge from 1884 to 1910. It was during these years that he worked primarily on issues in mathematics and logic. It was also during this time that he collaborated with Russell. The second main period, from 1910 to 1924, corresponds roughly to his time at London. During these years Whitehead concentrated mainly on issues in physics, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of education. The third main period corresponds roughly to his time at Harvard from 1924 onward. It was during this time that he worked primarily on issues in metaphysics.

1. Life and Works

The son of an Anglican clergyman, Whitehead graduated from Cambridge in 1884 and was elected a Fellow of Trinity College that same year. His marriage to Evelyn Wade six years later was largely a happy one and together they had a daughter (Jessie) and two sons (North and Eric). After moving to London, Whitehead served as president of the Aristotelian Society from 1922 to 1923. After moving to Harvard, he was elected to the British Academy in 1931. His moves to both London and Harvard were prompted in part by institutional regulations requiring mandatory retirement, although his resignation from Cambridge was also done partly in protest over how the University had chosen to discipline Andrew Forsyth, a friend and colleague whose affair with a married woman had become something of a local scandal.

In addition to Russell, Whitehead influenced many other students who became equally or more famous than their teacher, examiner or supervisor himself. For example: mathematicians G. H. Hardy and J. E. Littlewood; mathematical physicists Edmund Whittaker, Arthur Eddington, and James Jeans; economist J. M. Keynes; and philosophers Susanne Langer, Nelson Goodman, and Willard van Orman Quine. Whitehead did not, however, inspire any school of thought during his lifetime, and most of his students distanced themselves from parts of his teachings that they considered anachronistic. For example: Whitehead’s conviction that pure mathematics and applied mathematics should not be separated, but cross-fertilize each other, was not shared by Hardy, but seen as a remnant of the fading mixed mathematics tradition; after the birth of the theories of relativity and quantum physics, Whitehead’s method of abstracting some of the basic concepts of mathematical physics from common experiences seemed antiquated compared to Eddington’s method of world building, which aimed at constructing an experiment matching world from mathematical building blocks; when, due to Whitehead’s judgment as one of the examiners, Keynes had to rewrite his fellowship dissertation, Keynes raged against Whitehead, claiming that Whitehead had not bothered to try to understand Keynes’ novel approach to probability; and Whitehead’s main philosophical doctrine—that the world is composed of deeply interdependent processes and events, rather than mostly independent material things or objects—turned out to be largely the opposite of Russell’s doctrine of logical atomism, and his metaphysics was dispelled by the logical positivists from their dream land of pure scientific philosophy.

A short chronology of the major events in Whitehead’s life is below.

1861 Born February 15 in Ramsgate, Isle of Thanet, Kent, England.

1880 Enters Trinity College, Cambridge, with a scholarship in mathematics.

1884 Elected to the Apostles, the elite discussion club founded by Tennyson in the 1820s; graduates with a B.A. in Mathematics; elected a Fellow in Mathematics at Trinity.

1890 Meets Russell; marries Evelyn Wade.

1903 Elected a Fellow of the Royal Society as a result of his work on universal algebra, symbolic logic, and the foundations of mathematics.

1910 Resigns from Cambridge and moves to London.

1911 Appointed Lecturer at University College London.

1912 Elected President of both the South-Eastern Mathematical Association and the London branch of the Mathematical Association for the year 1913.

1914 Appointed Professor of Applied Mathematics at the Imperial College of Science and Technology.

1915 Elected President of the Mathematical Association for the two-year period 1915–1917.

1921 Meets Albert Einstein.

1922 Elected President of the Aristotelian Society for the one-year period 1922–1923.

1924 Appointed Professor of Philosophy at Harvard University.

1931 Elected a Fellow of the British Academy.

1937 Retires from Harvard.

1945 Awarded Order of Merit.

1947 Dies December 30 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

More detailed information about Whitehead’s life can be found in the comprehensive two-volume biography A.N. Whitehead: The Man and His Work (1985, 1990) by Victor Lowe and J.B. Schneewind. Paul Schilpp’s The Philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (1941) also includes a short autobiographical essay, in addition to providing a comprehensive critical overview of Whitehead’s thought and a detailed bibliography of his writings.

Other helpful introductions to Whitehead’s work include Victor Lowe’s Understanding Whitehead (1962), Stephen Franklin’s Speaking from the Depths (1990), Thomas Hosinski’s Stubborn Fact and Creative Advance (1993), Elizabeth Kraus’ The Metaphysics of Experience (1998), Robert Mesle’s Process-Relational Philosophy (2008), and John Cobb’s Whitehead Word Book (2015). Recommendable for the more advanced Whitehead student are Ivor Leclerc’s Whitehead’s Metaphysics (1958), Wolfe Mays’ The Philosophy of Whitehead (1959), Donald Sherburne’s A Whiteheadian Aesthetics (1961), Charles Hartshorne’s Whitehead’s Philosophy (1972), George Lucas’ The Rehabilitation of Whitehead (1989), David Griffin’s Whitehead’s Radically Different Postmodern Philosophy (2007), and Steven Shaviro’s Without Criteria (2009). For a chronology of Whitehead’s major publications, readers are encouraged to consult the Primary Literature section of the Bibliography below.

Attempts to sum up Whitehead’s life and influence are complicated by the fact that in accordance with his instructions, all his papers were destroyed following his death. As a result, there is no nachlass, except for papers retained by his colleagues and correspondents. Even so, it is instructive to recall the words of the late Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Felix Frankfurter:

From knowledge gained through the years of the personalities who in our day have affected American university life, I have for some time been convinced that no single figure has had such a pervasive influence as the late Professor Alfred North Whitehead. (New York Times, January 8, 1948)

Today Whitehead’s ideas continue to be felt and are revalued in varying degrees in all of the main areas in which he worked. A critical edition of his work is currently in the process of being prepared. A first volume, containing student notes of lectures given by Whitehead at Harvard in the academic year 1924–1925, has already been published by Edinburgh University Press in 2017, and more volumes are on their way.

2. Mathematics and Logic

Whitehead began his academic career at Trinity College, Cambridge where, starting in 1884, he taught for a quarter of a century. In 1890, Russell arrived as a student and during the 1890s the two men came into regular contact with one another. According to Russell,

Whitehead was extraordinarily perfect as a teacher. He took a personal interest in those with whom he had to deal and knew both their strong and their weak points. He would elicit from a pupil the best of which a pupil was capable. He was never repressive, or sarcastic, or superior, or any of the things that inferior teachers like to be. I think that in all the abler young men with whom he came in contact he inspired, as he did in me, a very real and lasting affection. (1956: 104)

By the early 1900s, both Whitehead and Russell had completed books on the foundations of mathematics. Whitehead’s 1898 A Treatise on Universal Algebra had resulted in his election to the Royal Society. Russell’s 1903 The Principles of Mathematics had expanded on several themes initially developed by Whitehead. Russell’s book also represented a decisive break from the neo-Kantian approach to mathematics Russell had developed six years earlier in his Essay on the Foundations of Geometry. Since the research for a proposed second volume of Russell’s Principles overlapped considerably with Whitehead’s own research for a planned second volume of his Universal Algebra, the two men began collaboration on what eventually would become Principia Mathematica (1910, 1912, 1913). According to Whitehead, they initially expected the research to take about a year to complete. In the end, they worked together on the project for a decade.

According to Whitehead—inspired by Hermann Grassmann—mathematics is the study of pattern:

mathematics is concerned with the investigation of patterns of connectedness, in abstraction from the particular relata and the particular modes of connection. (1933 [1967: 153])

In his Treatise on Universal Algebra, Whitehead took a generalized algebra—called ‘universal algebra’—to be the most appropriate tool for this study or investigation, but after meeting Giuseppe Peano during the section devoted to logic at the First International Congress of Philosophy in 1900, Whitehead and Russell became aware of the potential of symbolic logic to become the most appropriate tool to rigorously study mathematical patterns.

With the help of Whitehead, Russell extended Peano’s symbolic logic in order to be able to deal with all types of relations and, consequently, with all the patterns of relatedness that mathematicians study. In his Principles of Mathematics, Russell gave an account of the resulting new symbolic logic of classes and relations—called ‘mathematical logic’—as well as an outline of how to reconstruct all existing mathematics by means of this logic. After that, instead of only being a driving force behind the scenes, Whitehead became the public co-author of Russell of the actual and rigorous reconstruction of mathematics from logic. Russell often presented this reconstruction—giving rise to the publication of the three Principia Mathematica volumes—as the reduction of mathematics to logic, both qua definitions and qua proofs. And since the 1920s, following Rudolf Carnap, Whitehead and Russell’s project as well as similar reduction-to-logic projects, including the earlier project of Gottlob Frege, are classified under the header of ‘logicism’.

However, Sébastian Gandon has highlighted in his 2012 study Russell’s Unknown Logicism that Russell and Whitehead’s logicism project differed in at least one important respect from Frege’s logicism project. Frege adhered to a radical universalism, and wanted the mathematical content to be entirely determined from within the logical system. Russell and Whitehead, however, took into account the consensus, or took a stance in the ongoing discussions among mathematicians, with respect to the constitutive features of the already existing, ‘pre-logicized’ branches of mathematics, and then evaluated for each branch which of several possible types of relations were best suited to logically reconstruct it, while safeguarding its topic-specific features. Contrary to Frege, Whitehead and Russell tempered their urge for universalism to take into account the topic-specificity of the various mathematical branches, and as a working mathematician, Whitehead was well positioned to compare the pre-logicized mathematics with its reconstruction in the logical system.

For Russell, the logicism project originated from the dream of a rock-solid mathematics, no longer governed by Kantian intuition, but by logical rigor. Hence, the discovery of a devastating paradox—later called ‘Russell’s paradox’—at the heart of mathematical logic was a serious blow for Russell, and kicked off his search for a theory to prevent paradox. He actually came up with several theories, but retained the ramified theory of types in Principia Mathematica. Moreover, the ‘logicizing’ of arithmetic required extra-logical patchwork: the axioms of reducibility, infinity, and choice. None of this patchwork could ultimately satisfy Russell. His original dream evaporated and, looking back later in life, he wrote: “The splendid certainty which I had always hoped to find in mathematics was lost in a bewildering maze” (1959: 157).

Whitehead originally conceived of the logicism project as an improvement upon his algebraic project. Indeed, Whitehead’s transition from the solitary Universal Algebra project to the joint Principia Mathematica project was a transition from universal algebra to mathematical logic as the most appropriate symbolic language to embody mathematical patterns. It entailed a generalization from the embodiment of absolutely abstract patterns by means of algebraic forms of variables to their embodiment by means of propositional functions of real variables. Hardy was quite right in his review of the first volume of Principia Mathematica when he wrote: “mathematics, one may say, is the science of propositional functions” (quoted by Grattan-Guinness 1991: 173).

Whitehead saw mathematical logic as a tool to guide the mathematician’s essential activities of intuiting, articulating, and applying patterns, and he did not aim at replacing mathematical intuition (pattern recognition) with logical rigor. In the latter respect, Whitehead, from the start, was more like Henri Poincaré than Russell (cf. Desmet 2016a). Consequently, the discovery of paradox at the heart of mathematical logic was less of a blow to Whitehead than to Russell and, later in life, now and again, Whitehead simply reversed the Russellian order of generality and importance, writing that “symbolic logic” only represents “a minute fragment” of the possibilities of “the algebraic method” (1947 [1968: 129]).

For a more detailed account of the genesis of Principia Mathematica and Whitehead’s place in the philosophy of mathematics, cf. Smith 1953, Code 1985, Grattan-Guinness 2000 and 2002, Irvine 2009, Bostock 2010, Desmet 2010, N. Griffin et al. 2011, N. Griffin & Linsky 2013.

Following the completion of Principia, Whitehead and Russell began to go their separate ways (cf. Ramsden Eames 1989, Desmet & Weber 2010, Desmet & Rusu 2012). Perhaps inevitably, Russell’s anti-war activities and Whitehead’s loss of his youngest son during World War I led to something of a split between the two men. Nevertheless, the two remained on relatively good terms for the rest of their lives. To his credit, Russell comments in his Autobiography that when it came to their political differences, Whitehead

was more tolerant than I was, and it was much more my fault than his that these differences caused a diminution in the closeness of our friendship. (1956: 100)

3. Physics

Even with the publication of its three volumes, Principia Mathematica was incomplete. For example, the logical reconstruction of the various branches of geometry still needed to be completed and published. In fact, it was Whitehead’s task to do so by producing a fourth Principia Mathematica volume. However, this volume never saw the light of day. What Whitehead did publish were his repeated attempts to logically reconstruct the geometry of space and time, hence extending the logicism project from pure mathematics to applied mathematics or, put differently, from mathematics to physics—an extension which Russell greeted with enthusiasm and saw as an important step in the deployment of his new philosophical method of logical analysis.

At first, Whitehead focused on the geometry of space.

When Whitehead and Russell logicized the concept of number, their starting point was our intuition of equinumerous classes of individuals—for example, our recognition that the class of dwarfs in the fairy tale of Snow White (Doc, Grumpy, Happy, Sleepy, Bashful, Sneezy, Dopey) and the class of days in a week (from Monday to Sunday) have ‘something’ in common, namely, the something we call ‘seven.’ Then they logically defined (i) classes C and C′ to be equinumerous when there is a one-to-one relation that correlates each of the members of C with one member of C′, and (ii) the number of a class C as the class of all the classes that are equinumerous with C.

When Whitehead logicized the space of physics, his starting point was our intuition of spatial volumes and of how one volume may contain (or extend over) another, giving rise to the (mereo)logical relation of containment (or extension) in the class of volumes, and to the concept of converging series of volumes—think, for example, of a series of Russian dolls, one contained in the other, but idealized to ever smaller dolls. Whitehead made all this rigorous and then, crudely put, defined the points from which to further construct the geometry of space.

There is a striking resemblance between Whitehead’s construction of points and the construction of real numbers by Georg Cantor, who had been one of Whitehead and Russell’s main sources of inspiration next to Peano. Indeed, Whitehead defined points as equivalence classes of converging series of volumes, and Cantor defined real numbers as equivalence classes of converging series of rational numbers. Moreover, because Whitehead’s basic geometrical entities of geometry are not (as in Euclid) extensionless points but volumes, Whitehead can be seen as one of the fathers of point-free geometry; and because Whitehead’s basic geometrical relation is the mereological (or part-whole) relation of extension, he can also be seen as one of the founders of mereology (and even, when we take into account his later work on this topic in part IV of Process and Reality, of mereotopology).

“Last night”, Whitehead wrote to Russell on 3 September 1911,

the idea suddenly flashed on me that time could be treated in exactly the same way as I have now got space (which is a picture of beauty, by the bye). (Unpublished letter kept in The Bertrand Russell Archives at McMaster University)

Shortly after, Whitehead must have learned about Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity (STR) because in a letter to Wildon Carr on 10 July 1912, Russell suggested to the Honorary Secretary of the Aristotelian Society that Whitehead possibly might deliver a paper on the principle of relativity, and added: “I know he has been going into the subject”. Anyhow, in the early years of the second decade of the twentieth century, Whitehead’s interest shifted from the logical reconstruction of the Euclidean space of classical physics to the logical reconstruction of the Minkowskian space-time of the STR.

A first step to go from space to space-time was the replacement of (our intuition of) spatial volumes with (our intuition of) spatio-temporal regions (or events) as the basis of the construction (so that, for example, a point of space-time could be defined as an equivalence class of converging spatio-temporal regions). However, whereas Whitehead had constructed the Euclidean distance based on our intuition of cases of spatial congruence (for example, of two parallel straight line segments being equally long), he now struggled to construct the Minkowskian metric in terms of a concept of spatio-temporal congruence, based on a kind of merger of our intuition of cases of spatial congruence and our intuition of cases of temporal congruence (for example, of two candles taking equally long to burn out).

So, as a second step, Whitehead introduced a second relation in the class of spatio-temporal regions next to the relation of extension, namely, the relation of cogredience, based on our intuition of rest or motion. Whitehead’s use of this relation gave rise to a constant k, which allowed him to merge spatial and temporal congruence, and which appeared in his formula for the metric of space-time. When Whitehead equated k with c2 (the square of the speed of light) his metric became equal to the Minkowskian metric.

Whitehead’s most detailed account of this reconstruction of the Minkowskian space-time of the STR was given in his 1919 book, An Enquiry concerning the Principles of Natural Knowledge, but he also offered a less technical account in his 1920 book, The Concept of Nature.

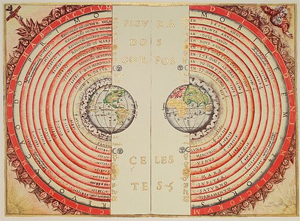

Whitehead first learned about Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity (GTR) in 1916. He admired Einstein’s new mathematical theory of gravitation, but rejected Einstein’s explanation of gravitation for not being coherent with some of our basic intuitions. Einstein explained the gravitational motion of a free mass-particle in the neighborhood of a heavy mass as due to the curvature of space-time caused by this mass. According to Whitehead, the theoretical concept of a contingently curved space-time does not cohere with our measurement practices; they are based on the essential uniformity of the texture of our spatial and temporal intuition.

In general, Whitehead opposed the modern scientist’s attitude of dropping the requirement of coherence with our basic intuitions, and he revolted against the issuing bifurcation of nature into the world of science and that of intuition. In particular, as Einstein’s critic, he set out to give an alternative rendering of the GTR—an alternative that passed not only what Whitehead called “the narrow gauge”, which tests a theory’s empirical adequacy, but also what he called “the broad gauge”, which tests its coherence with our basic intuitions.

In 1920, first in a newspaper article (reprinted in Essays in Science and Philosophy), and then in a lecture (published as Chapter VIII of Concept of Nature), Whitehead made public an outline of his alternative to Einstein’s GTR. In 1921, Whitehead had the opportunity to discuss matters with Einstein himself. And finally, in 1922, Whitehead published a book with a more detailed account of his alternative theory of gravitation (ATG)—The Principle of Relativity.

According to Whitehead, the Maxwell-Lorentz theory of electrodynamics (unlike Einstein’s GTR) could be conceived as coherent with our basic intuitions—even in its four-dimensional format, namely, by elaborating Minkowski’s electromagnetic worldview. Hence, Whitehead developed his ATG in close analogy with the theory of electrodynamics. He replaced Einstein’s geometric explanation with an electrodynamics-like explanation. Whitehead explained the gravitational motion of a free mass-particle as due to a field action determined by retarded wave-potentials propagating in a uniform space-time from the source masses to the free mass-particle.

It is important to stress that Whitehead had no intention of improving the predictive content of Einstein’s GTR, only the explanatory content. However, Whitehead’s replacement of Einstein’s explanation with an alternative explanation entailed a replacement of Einstein’s formulae with alternative formulae; and these different formulae implied different predictions. So it would be incorrect to say that Whitehead’s ATG is empirically equivalent to Einstein’s GTR. What can be claimed, however, is that for a long time Whitehead’s theory was experimentally indistinguishable from Einstein’s theory.

In fact, like Einstein’s GTR, Whitehead’s ATG leads to Newton’s theory of gravitation as a first approximation. Also (as shown by Eddington in 1924 and J. L. Synge in 1952) Einstein’s and Whitehead’s theories of gravitation lead to an identical solution for the problem of determining the gravitational field of a single, static, and spherically symmetric body—the Schwarzschild solution. This implies, for example, that Einstein’s GTR and Whitehead’s ATG lead to the exact same predictions not only with respect to the precession of the perihelion of Mercury and the bending of starlight in the gravitational field of the sun (as already shown by Whitehead in 1922 and William Temple in 1924) but also with respect to the red-shift of the spectral lines of light emitted by atoms in the gravitational field of the sun (contrary to Whitehead’s own conclusion in 1922, which was based on a highly schematized and soon outdated model of the molecule). Moreover (as shown by R. J. Russell and Christoph Wassermann in 1986 and published in 2004) Einstein’s and Whitehead’s theories of gravitation also lead to an identical solution for the problem of determining the gravitational field of a single, rotating, and axially symmetric body—the Kerr solution.

Einstein’s and Whitehead’s predictions become different, however, when considering more than one body. Indeed, Einstein’s equation of gravitation is non-linear while Whitehead’s is linear; and this divergence qua mathematics implies a divergence qua predictions in the case of two or more bodies. For example (as shown by G. L. Clark in 1954) the two theories lead to different predictions with respect to the motion of double stars. The predictive divergence in the case of two bodies, however, is quite small, and until recently experimental techniques were not sufficiently refined to confirm either Einstein’s predictions or Whitehead’s, for example, with respect to double stars. In 2008, based on a precise timing of the pulsar B1913+16 in the Hulse-Taylor binary system, Einstein’s predictions with respect to the motion of double stars were confirmed, and Whitehead’s refuted (by Gary Gibbons and Clifford Will). The important fact from the viewpoint of the philosophy of science is not that, since the 1970s, now and again, a physicist rose to claim the experimental refutation of Whitehead’s ATG, but that for decades it was experimentally indistinguishable from Einstein’s GTR, hence refuting two modern dogmas. First, that theory choice is solely based on empirical facts. Clearly, next to facts, values—especially aesthetic values—are at play as well. Second, that the history of science is a succession of victories over the army of our misleading intuitions, each success of science must be interpreted as a defeat of intuition, and a truth cannot be scientific unless it hurts human intuition. Surely, we can be scientific without taming the authority of our intuition and without engaging in the disastrous race to disenchant nature and humankind.

For a more detailed account of Whitehead’s involvement with Einstein’s STR and GTR, cf. Palter 1960, Von Ranke 1997, Herstein 2006 and Desmet 2011, 2016b, and 2016c.

4. Philosophy of Science

Whitehead’s reconstruction of the space-time of the STR and his ATG make clear (i) that his main methodological requirement in the philosophy of science is that physical theories should cohere with our intuitions of the relatedness of nature (of the relations of extension, congruence, cogredience, causality, etc.), and (ii) that his paradigm of what a theory of physics should be like is the Maxwell-Lorentz theory of electrodynamics. And indeed, in his philosophy of science, Whitehead rejects David Hume’s “sensationalist empiricism” (1929c [1985: 57]) and Isaac Newton’s “scientific materialism” (1926a [1967: 17]). Instead Whitehead promotes (i) a radical empiricist methodology, which relies on our perception, not only of sense data (colors, sounds, smells, etc.) but also of a manifold of natural relations, and (ii) an electrodynamics-like worldview, in which the fundamental concepts are no longer simply located substances or bits of matter, but internally related processes and events.

“Modern physical science”, Whitehead wrote,

is the issue of a coordinated effort, sustained for more than three centuries, to understand those activities of Nature by reason of which the transitions of sense-perception occur. (1934 [2011: 65])

But according to Whitehead, Hume’s sensationalist empiricism has undermined the idea that our perception can reveal those activities, and Newton’s scientific materialism has failed to render his formulae of motion and gravitation intelligible.

Whitehead was dissatisfied with Hume’s reduction of perception to sense perception because, as Hume discovered, pure sense perception reveals a succession of spatial patterns of impressions of color, sound, smell, etc. (a procession of forms of sense data), but it does not reveal any causal relatedness to interpret it (any form of process to render it intelligible). In fact, all “relatedness of nature”, and not only its causal relatedness, was “demolished by Hume’s youthful skepticism” (1922 [2004: 13]) and conceived as the outcome of mere psychological association. Whitehead wrote:

Sense-perception, for all its practical importance, is very superficial in its disclosure of the nature of things. … My quarrel with [Hume] concerns [his] exclusive stress upon sense-perception for the provision of data respecting Nature. Sense-perception does not provide the data in terms of which we interpret it. (1934 [2011: 21])

Whitehead was also dissatisfied with Newton’s scientific materialism,

which presupposes the ultimate fact of an irreducible brute matter, or material, spread through space in a flux of configurations. In itself such a material is senseless, valueless, purposeless. It just does what it does do, following a fixed routine imposed by external relations which do not spring from the nature of its being. (1926a [1967: 17])

Whitehead rejected Newton’s conception of nature as the succession of instants of spatial distribution of bits of matter for two reasons. First: the concept of a “durationless” instant, “without reference to any other instant”, renders unintelligible the concepts of “velocity at an instant” and “momentum at an instant” as well as the equations of motion involving these concepts (1934 [2011: 47]). Second: the concept of self-sufficient and isolated bits of matter, having “the property of simple location in space and time” (1926a [1967: 49]), cannot “give the slightest warrant for the law of gravitation” that Newton postulated (1934 [2011: 34]). Whitehead wrote:

Newton’s methodology for physics was an overwhelming success. But the forces which he introduced left Nature still without meaning or value. In the essence of a material body—in its mass, motion, and shape—there was no reason for the law of gravitation. (1934 [2011: 23])

There is merely a formula for succession. But there is an absence of understandable causation for that formula for that succession. (1934 [2011: 53–54])