by Gabriella Borter

March 20, 2019

American Physical Anthropology

A brief survey of American anthropology at the end of World War I shows that little mattered outside the East Coast. Although there were departments of anthropology in other parts of the country such as Chicago and San Francisco, and though the anatomist Wingate Todd at Case Western Reserve worked on physical anthropology, the undisputed center was in the East. Distance prevented anthropologists outside of Boston, New York and Washington from participating in professional activity. Committee membership particularly illustrates this phenomenon. In the capital, an active local anthropological society together with the Smithsonian Institution partially compensated for the lack of a major university center. Washington’s prime was before World War I, but it remained active during the interwar years. Harvard’s anthropology department together with its affiliated Peabody Museum was second only to New York in significance for the profession. During most of this period, Ronald Dixon, Alfred Tozzer, and Earnest Hooton were Harvard’s leading anthropologists. While certainly very different from each other, they maintained the façade of a team. The distance from New York meant that the Harvard anthropologists could profess partial unity based upon geography, at the same time it was not too far for Harvard to be secluded from the centers of power.

As the intellectual center of the country, New York attracted several active anthropological institutions, with close contacts to major philanthropic sources. The Galton Society and Cold Spring Harbor were the centers for the eugenicists and racists, while the New School for Social Research provided a liberal outlet for the Columbia faculty. Both the American Museum of Natural History and Columbia University were the core of anthropological activity and employed anthropologists of liberal and conservative commitments. Despite the ideological diversity, there was contact, at times close, between the opposing camps. The interaction resulted partly from institutional constraints, and partly from association with a larger anthropological community that included many neutrals. Surrounded by, and being part of, the intellectual activity of the city, New York anthropologists were, generally speaking, much more involved in public debates and retreated far less into the ivory tower. Columbia’s anthropology was synonymous with Boas, but he was the exception and many faculty members kept close contacts with eugenics circles. A comparable situation existed in the American Museum where the liberal and conservative groups worked together, though not in cooperation. Henry Fairfield Osborn, the President of the Museum was a close associate of Madison Grant and an adamant Anglo-Saxon supremacist. Nevertheless Boas worked in the Museum for several years, as did Robert Lowie, and later Harry Shapiro and Margaret Mead. The tension and rivalry made a non-partisan approach difficult, and therefore neutrality was not as much a determining force in New York, as it was in Washington and Cambridge.

-- The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concepts of Race in Britain and the United States Between the World Wars, by Elazar Barkan

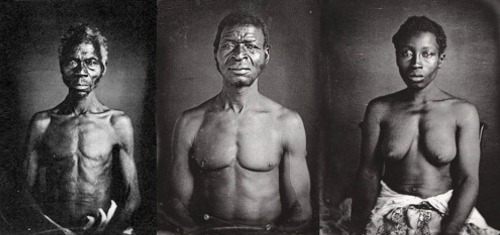

From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried is a series of 34 "found" photographs that Weems has re-photographed and significantly altered -- tinting, cropping, framing, and inscribing with verbal text. Some of the photographs in this series, the ones upon which I will focus my reading, were long housed in the archives of Harvard's Peabody Museum (Figures 2.2 and 2.3).

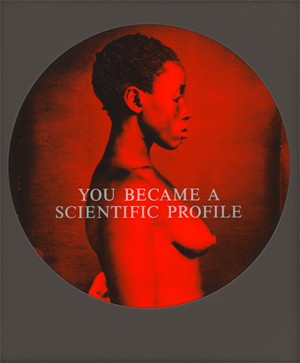

2.2 Carrie Mae Weems (American born 1953). "You Became A Scientific Profile." 1995. From the series, From Here I Saw What Happened And I Cried. Chromogenic color print with sand-blasted text on glass. 26-1/2 x 22-3/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Carrie Mae Weems, and the Jack Shainman Gallery, NY.

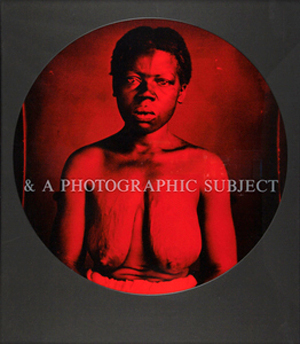

2.3 Carrie Mae Weems (American, born 1953). "& A Photographic Subject." 1995. From the series, From Here I Saw What Happened And I Cried. Chromogenic color print with sand-blasted text on glass. 26-1/2 x 22-3/4 inches. Courtesy of the artist, Carrie Mae Weems, and the Jack Shainman Gallery, NY.

These photographs were originally taken as part of a mid-nineteenth-century anthropological study in which enslaved father-daughter pairs were photographed (by daguerreotype) in a grievous effort to "document" their supposedly subhuman physiognomy. Anthropologist Louis Agassiz and photographer Joseph T. Zealy together were responsible for the mid-nineteenth-century production of these photographs that were intended as tools of scientific enquiry. Herein surfaces already an aspect of the complex ideological underpinnings of photographic documentation, a problematic that Weems's series for Hidden Witness magisterially invokes. Weems's re-photographing of the daguerreotypes of enslaved Americans raises the following question: what, exactly, did Zealy and Agassiz 's daguerreotypes, before Weems's altering of the images, document? With the mid-nineteenth-century anthropological lens that drove Agassiz removed, we surely no longer interpret the photographs, preserved in Harvard's Peabody Museum, as documenting the brutal claims of racism to lodge in physiognomy. That is, in Weems's retake of these daguerreotypes, the photographs' original documentary intent is now obviated. But there are traces that remain: a history of racism, linkages between early anthropology and racism, and also the forceful residue of insisted-upon personhood that yet gleams in the eyes of the humiliated objects of study, whom Weems witnesses by re-photographing.

The haunting gesture of Weems's re-presentation of the Peabody Museum photographs in From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried -- photographs that do not make up the bulk of her series, but, for me, form the ethical crux of the series -- has not escaped criticism. Some prominent scholars have raised questions focusing on the ethics of Weems reprinting these disturbing images at all. In a conference paper at Duke University, Cherise Smith raised the question of whether by re-presenting these photographs of slaves at their moment of debasement -- the moment at which the human being is forced to appear as an object of study for the anthropologist (the scientist who, in the case of these photographs, was conducting his study specifically to prove his subjects subhuman) -- Weems does not in fact violate certain ethical codes, codes that would urge us to protect the dead from humiliation.

Smith's conference paper effectively recants her glowing interpretation, in "Fragmented Documents." At the conference at Duke, Smith critiqued Weems's gesture of exposing these humiliated photographic subjects. Likewise, Andrea Liss, in an early and overall positive review of the original Getty exhibition, raises the question with regard to Weems's From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried concerning "how to represent the victim without re-victimizing the victim." But surely the problem here is more complex than re-victimization. For the difficulty inheres in the ethical knot of how representation, particularly in the case of Weems's installation re-presenting images of the dead, may be said to revictimize the dead.

Weems herself has voiced ambivalence about the series, which was so admired by the First Lady, Michelle Obama, as to elicit for Weems an invitation to the White House. Weems states that the series makes her cry, a striking fusion of her role as artist and as witness, a statement that comes close to answering the question of who is the "I" in the sentence, "And I Cried" that closes the series. Weems states further that the series made her painfully aware of the power difference between the photographer, who has photo-power, and the photographic subject, vulnerable in her/his embodiment. This series, of all her work, is the only one of which Weems claims "I cannot live with it," a statement that could be interpreted to mean she feels guilt over having produced the series, though Weems goes on to explain that she means she cannot have images from the series in her house, where she lives. This series is also Weems's signal use of the technique of rephotographing.

The Peabody Museum daguerreotypes, the re-photographs of which constitute part of Weems's installation, were taken some 150 years before Weems's installation was created, and the enslaved Americans whose images the Peabody Museum kept in its files are no longer alive to be re-victimized in a straightforward sense. In a strictly physical sense, those who suffered the humiliation of Agassiz's "study" are now beyond further harm. It seems imperative, then, that we re-explore, adjust, and tighten our notion of how re-victimization can be enacted against the dead through reproduction of the images of the dead. Can re-victimization be spectral, purely performative, strictly textual? For example, the young woman across whose chest Weems places the text "You Became a Scientific Profile" cannot now walk in and see the image of herself in the Getty or MoMA (where the series is owned in the museum's permanent collection). This nineteenth-century woman cannot confront her own image and feel rage, shame, grief, or desire for vengeance -- whatever we might imagine ourselves feeling were we her.

And yet, confronted specifically with this image, we are caught by the possible repetition of debasement of the, now public, mistreated feminine figure (Figure 2.2). I am interested, in particular, in Liss's response to this young woman's image, as well as to another image in the series of a young woman offering her sex, across which Weems has inscribed the text "You Became Playmate to the Patriarch," insofar as Liss instinctively brings these women back to life -- invoking their former inarguable status as victims and verbally moving to protect them from revictimization.

And Eddie Chambers, in his review of Weems's work exhibited at Cafe Gallery Projects in London, states that "a significant number of the more racist images ought really to be set to one side and not given periodic kisses of life even if such resuscitation takes place by an African American artist under the guise of a knowing and artistic deconstruction and engagement with the U.S.A.'s racist past." The spectacle dimensions of sadism -- not only enacted on the vulnerable body, but also enacted through the gaze -- carry a unique ethical freight (again, I am here using the term sadism to indicate cruelty inflicted in a context of absolute relational vulnerability). The ethical problematic of how representation inscribes violence is raised not only by Weems's From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, but also by the complex critical responses to Weems's work. Cherise Smith's objection to this series is made solely on ethical grounds. What Smith, Liss, and Chambers uncannily share, despite their diverse sophistication as critics of visual objects and culture, is a slide into interpreting these representations -- photographs retaken, cropped, framed, tinted, and inscribed, objects functioning on the representational axis par excellence -- as not only vivid but somehow alive, available to be re-victimized, given a bad kiss of life: revenants of representation.

Weems's work is vulnerable to such hypothetical accusations of sadism not only as history and documentary, but also as aesthetic mark. For implicit in the complaints of Smith, Liss, and Chambers against From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried is a critical gesture of holding Weems responsible for the production of revenants: as if, vampire-like, Weems drew the lifeblood of her art from these wounded innocents (the enslaved Americans represented in Agassiz and Zealy's daguerreotypes), and in so doing, made them revenants, gave them an unhallowed, unasked-for second life. Chambers states that Weems has worked under a "guise," as if Weems should not be trusted -- a masked woman, a sadist, a dominatrix wearing a guise herself. This image of Weems as a masked dominatrix presiding over the victimized images of the enslaved fathers and daughters who were already victims of Zealy and Agassiz is profoundly troubling. Weems's gaze, for these critics, comes in to unholy alliance with the gaze of those who first documented the "photographic subject" whom she reprints.

In other words, Chambers interprets Weems the artist as having a responsibility not, as he explicitly states, in her role of presenting images from the Peabody Museum to the public, but rather more, as he intimates, for looking at the photographs of enslaved Americans and not turning away, and also not allowing her audience to turn away. In the view of Chambers, the most ethical stance would be not to look at all at these images, images that unquestionably humiliate their subjects. In looking, Chambers implies, Weems becomes a sadist: a guise or mask crosses her face as she holds her gaze on these sadistically produced images. Indeed, in revealing, by reproducing, what might be seen as the origins of documentary photography (i.e., "scientific" documentation through photography), Weems bears down on the ethical problematic of the gaze at the heart of the conceit of documentary photography.

Cherise Smith has beautifully traced the originary complexity of documentary photography, with regards to the African American community, writing on Weems's indebtedness to and departures from DeCarava. Crucially, one must interpret Weems's From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried as already itself posing a critique and simultaneous intensification of the claims of documentary photography. The series critiques the very notion that what Zealy and Agassiz set out to "document" was ever in any sense real -- in fact, it was utterly ideological. The problematic of documentary photography -- that it presumes a reality when that very subtext may always already in fact be ideological -- is revealed in Weems's installation. To be sure, the series documents the savagery of an earlier ideology, even as the photographs that Weems represents were also thought, in their day, to be "documents."

However, I am less interested in querying the difficulties and ambiguities of the status of documentary photography -- the question of just how deceptive the conceit of photography as documentation is -- and more concerned with questions around gender and the gaze raised by Weems's controversial series. In particular, I want to intervene in received notions of the passive, heteronormative, presumptively feminine gaze by reconsidering how the figure of a woman watching violence plays through both the conceptualization and the reception of Weems's offering for the Hidden Witness exhibition. That is, regardless of the complex reengagement of documentary that most certainly occurs in Weems's installation, the aspect of this contretemps to which I want to point is the fact that the series is framed within the visual field of a feminine watcher -- a fact ironically brought forward by critics instinctively interpreting Weems as a character in her own series, a masked dominatrix coldly surveying suffering "photographic subjects" (to borrow the phrase from Weems's own taunting inscription in the series). To rephrase with an emphasis on the nexus of gender and watching, the problematic figure of a woman watching sadism plays through Weems's From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried in ways that both surpass and support the series' interrogation of the documentary genre.

As I have suggested in quoting Liss and Chambers, part of the complex reception of this series seems to be viewer discomfort with images of others' humiliation -- not simply because those images are re-photographed by Weems, but more so because recorded in the images is the history of their being seen by Weems. The record of this moment, of Weems herself seeing the images, is recorded in the tinting, cropping, framing, inscribing, claiming with text that marks the representations. Weems's gender, in particular, seems to trouble Chambers, who envisions Weems erotically kissing the images she reprints -- when, in fact, the series is not in the least erotically titillating. By implication, in presenting these rephotographed photographs, Weems makes very clear that she saw them, was able to continue looking at them, and could look at them with an eye steely enough to allow her not only to re-photograph, but also to remake the images.

The gesture of locating the anthropological daguerreotypes in the Peabody Museum that inaugurates the completed installation articulates Weems in the role of the witness, responding quite directly to the charge of the Hidden Witness exhibition. One imagines Weems's first encounter with the images at the Peabody, their very residence in that bastion of scientific history itself a troubling allegory of the persistence of memory across generations. As witness to the images of sadism recorded in the photographs created by Zealy for Agassiz (the one whose gaze precedes that of her audience), Weems's burden is inflected by gender. Insofar as Weems selects, re-photographs, tints, blasts text across, and generally reclaims the images, she as a woman who looks -- an artist known socially and professionally as a woman -- centers the installation. Weems's earlier The Kitchen Table Series (1990), for example, articulated her apparent identification of a confluence of the claims of femininity and the possibility of representing gender by representing the gendered gaze. While not autobiographical, The Kitchen Table Series does unmistakably instate a feminine gaze -- an entity given a representational status of the real in the context of that powerful floating signifier, the kitchen table. To argue as I do that Weems, in the installation of From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, enacts a feminine gaze is not an argument that would seem at variance with the artist's practice and conceptualization of gendered ways of seeing.

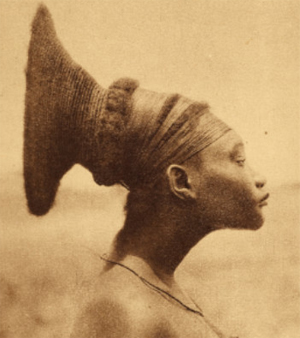

Indeed, a womanly watcher -- a feminine figure who witnesses and watches -- not only is implicit in the series' construction but also explicitly is placed in Weems's From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried series. The piece is framed by George Specht's colonialist 1925 photograph (for National Geographic) "Nobosodrou, Femme Mangetu."

Nobosodrou, by George Specht, 1924

This blue-tinted, reprinted, photographed, feminine profile is positioned by Weems to regard, as a witness, the red-tinted images within the series: to figuratively stand as the "I" who "Saw What Happened" and "Cried." At the inauguration of the series, this profile image looks towards the series of reprinted red-tinted photographs, and the same profile in mirror looks back across the series at its close. The Specht profile tinted blue is marked as the cool witness figure, the cool customer who claims to be crying (as a point of fact, for the words "And I Cried" are written across the second image) but looks anything but tearful. With the words "From Here I Saw What Happened" on the first image and "And I Cried" on the second image, in duplicate the Specht profile re-photographs gaze towards each other across the field of red-tinted debasement and grief contained in the other images of the series. These profile images bookend the series, enclosing the humiliated subjects contained in the photographs that are tinted red. This gesture of the witness, instantiated by the re-photograph of Specht's work, ethically anchors the series, mournfully recuperating the woman's elegant beauty.

That this witness, figuratively performed by the Specht image, is a woman is not incidental to Weems's project. For much of the worst humiliation imaged in From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried is humiliation recorded visually on the body of a woman. Notably, A. M. Weaver argues that Weems "tells her stories from the perspective of a black woman, indeed she herself is invariably [my italics] the protagonist in her private/public dramas -- it is always her life, her voice, her body that represents the scope of human reality." Deborah Willis likewise observes that "For more than three decades, Weems has focused her lens on her own body and used her writings to extend the conversation." Willis, who has made clear the importance of the explicit witness figure of the artist in Weems's later work, goes on to claim that even when Weems is not pictured in her own work she is, almost mystically, evoked by the images she photographs or re-photographs.

How are we to interpret Weems's offering for the Hidden Witness exhibition in the context of such insistent, almost privative, gendering as is recorded, according to Weaver, in Weems's work? That is, how shall we interpret, in particular, Weems's depiction of the humiliation of enslaved women framed within the elegant and emphatically not enslaved gaze of the Specht photograph -- the woman titled "Nobosodrou," who is herself, it must be made clear, a photographic subject? Is Weems, as Weaver suggests, the real subject of this series? And, if so, which figure is she? The humiliated enslaved person in a photograph by whose caption she is called Delia? Or the elegant Nobosodrou? Weaver's claim seems to founder on this difficult series -- a series that breaks apart and reveals the violence implicit in the conceit of the witness, not to mention to more subtly and insidiously violent strictures of femininity. My suggestion, developing from Willis, is that although Weems is not present visibly in these re-photographed images in From Here I saw What Happened and I Cried, instead Weems invokes a provocatively feminine "I" who should see and should cry. Weems's gaze is the eye that contains the series and this eye is articulated in the act of re-photographing daguerrotypes originally taken by nineteenth-century white men. Her resistance to their gaze is in developing the trope of witnessing.

-- Witnessing Sadism in Texts of the American South: Women, Specularity, and the Poetics of Subjectivity, by Professor Claire Raymond

Earnest Albert Hooton (November 20, 1887 – May 3, 1954) was an American physical anthropologist known for his work on racial classification and his popular writings such as the book Up From The Ape. Hooton sat on the Committee on the Negro, a group that "focused on the anatomy of blacks and reflected the racism of the time."... During this time, he was also Curator of Somatology at the nearby Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

-- Earnest Hooton, by Wikipedia

***

Over a period of fourteen years (1948-1962) that followed his doctoral training at Harvard, [Lloyd Cabot] Briggs established a home in Algiers (at 7 rue Pierre Viala) and purchased a farm nearby -- these Briggs shared with Danus, who served as something of an assistant to her husband, occasionally accompanying him on his travels. All the while, Briggs was amassing an extraordinary private collection of Tuareg art, especially of the Algerian Sahara. Some of these objects he purchased from other collectors, including Reygasse and a number of French army officers, researchers, and colonial administrators; some he purchased on behalf of the Peabody Museum through the American School for Prehistoric Research, an Algiers-based institution affiliated with the Peabody. Following Briggs's wishes, his family would donate the bulk of his extraordinary collection to the Peabody after his death.

Even before Briggs journeyed to the Sahara with Reygasse, he was writing The Living Races of the Sahara Desert.

-- Saharan Jews and the Fate of French Algeria, by Sarah Abrevaya Stein

(Reuters) - A descendant of an American slave on Wednesday sued Harvard University to gain possession of photos of her great-great-great grandfather that the school commissioned in 1850 on behalf of a professor trying to prove the inferiority of black people.

Tamara Lanier listens as her lawyer speaks to the media about a lawsuit accusing Harvard University of the monetization of photographic images of her great-great-great grandfather, an enslaved African man named Renty, and his daughter Delia, outside of the Harvard Club in New York, U.S., March 20, 2019. REUTERS/Lucas Jackson

The photos, depicting a black man named Renty and his daughter Delia, were taken as part of a study by Harvard Professor Louis Agassiz and are among the earliest known photos of American slaves. They are currently kept at the Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnography at Harvard’s Cambridge, Massachusetts campus.

A representative for Harvard declined to comment and said the university had not yet been served with the complaint.

Tamara Lanier of Norwich, Connecticut, who claims to be the great-great-great-granddaughter of Renty, accused Harvard of celebrating its former professor who studied “racist pseudoscience” and profiting from photos that were taken without Renty and his daughter’s consent.

“What I hope we’re able to accomplish is to show the world who Renty is,” Lanier said at a news conference in New York. “I think this case is important because it will test the moral climate of this country and force this country to reckon with its long history of racism.”

Agassiz encountered Renty and Delia when he was touring plantations in South Carolina for a research project sanctioned by Harvard that sought to support his view that black people were a different species, according to the lawsuit.

Lanier, who filed the lawsuit in Middlesex County Superior Court in Massachusetts, established her relationship to the photographed slaves with family oral history and genealogical information, her lawyers said. She previously asked the university to give her the photos, but Harvard refused, she said.

“By denying Ms. Lanier’s superior claim to the daguerreotypes, Harvard is perpetuating the systematic subversion of black property rights that began during slavery and continued for a century thereafter,” the complaint said, referring to an early form of photography.

In addition to gaining possession of the photos, Lanier is seeking compensation for emotional distress and Harvard’s acknowledgement that it was “complicit in perpetuating and justifying the institution of slavery.”

Harvard is the latest elite academic institution criticized for its failure to reckon with a racist past. In 2016, a member of Yale University’s kitchen staff shattered a stained glass window depicting slaves in a field, drawing national attention and overwhelming support from students who took up his protest against what they said was Yale’s implicit endorsement of a racist history.

Reporting by Gabriella Borter; Editing by Frank McGurty and Cynthia Osterman

************************

Harvard Gets Slapped With A Lawsuit

by Nana

everyevery

2019

Harvard University is being sued over photographs of African slaves. The descendants of the man from the photograph are suing the university.

Tamara Lanier, a direct descendant is demanding that Harvard turn over the images, recognize her lineage and pay unspecified damages.

The enslaved African man named Renty and his daughter Delia were stripped and forced to pose for images commissioned by a Swiss-born Harvard professor who espoused a theory that Africans and African-Americans were inferior to whites.

170 years later, Renty and Delia “remain enslaved” by the Ivy League university which is being accused of the “wrongful seizure, possession and expropriation” of the photographs of his great-great-great-granddaughter, Tamara, who wants the photos back.

Lanier, who refers to her great-great-great grandfather as “Papa Renty,” said she learned from years of research and oral history from her family that he was born in Africa, kidnapped by slave merchants and enslaved on a South Carolina plantation. He taught himself and other slaves to read and led secret Bible readings and study on the plantation.

The images were long forgotten until an employee of Harvard’s Peabody Museum discovered them in the museum’s attic in 1976, the lawsuit said.

The employee, Ellie Reichlin, was concerned for the families of the men and women in the images but it was reported that Harvard made no effort to locate their descendants.

Lanier continued gathering evidence of her heritage and, in 2016, contacted the Harvard Crimson, the student newspaper, with her story.

She went to Cambridge for an interview but later learned that her story would not be told because of “concerns the Peabody Museum has raised,” the suit said.

The lawsuit claims the photos of Renty and Delia were taken a few years after Harvard had recruited Agassiz, whose field of study was a branch of zoology that grouped living things based on anatomical characteristics and hierarchical order.

The lawsuit said, “It was an act of both love and resistance that Renty and Delia’s kin kept their memories and stories alive for well over a century. It is unconscionable that Harvard will not allow Ms. Lanier to, at long last, bring Renty and Delia home.”