Arthur Balfourby Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/2/20

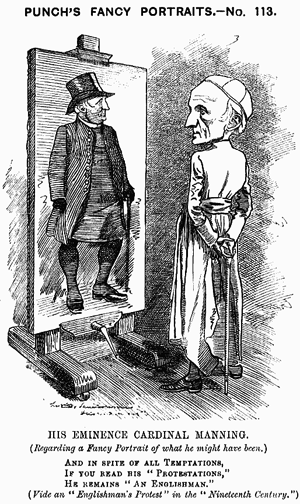

Continuing their discussion of the membership of "The Society of the Elect,"

Stead asked permission to bring in

Milner and

Brett.

Rhodes agreed, so they telegraphed at once to

Brett, who arrived in two hours. They then drew up the following "ideal arrangement' for the society:

1. General of the Society:

Rhodes2. Junta of Three: (1)

Stead, (2)

Brett, (3)

Milner3. Circle of Initiates: (1)

Cardinal Manning, (2)

General Booth, (3)

Bramwell Booth, (4)

"Little" [Harry] Johnston, (5)

Albert Grey, (6)

Arthur Balfour4. The Association of Helpers

5. A College, under Professor Seeley, to be established to train people in the English-speaking idea."

Within the next few weeks Stead had another talk with Rhodes and a talk with Milner, who was "filled with admiration" for the scheme, according to Stead's notes as published by Sir Frederick Whyte.

-- The Anglo-American Establishment: From Rhodes to Cliveden, by Carroll Quigley

The Right Honourable The Earl of Balfour KG OM PC FRS FBA DL

Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

In office: 12 July 1902 – 4 December 1905

Monarch: Edward VII

Preceded by: The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Succeeded by: Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman

Lord President of the Council

In office: 27 April 1925 – 4 June 1929

Prime Minister: Stanley Baldwin

Preceded by: The Marquess Curzon of Kedleston

Succeeded by: The Lord Parmoor

In office: 23 October 1919 – 19 October 1922

Prime Minister: David Lloyd George

Preceded by: The Earl Curzon of Kedleston

Succeeded by: The 4th Marquess of Salisbury

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

In office: 10 December 1916 – 23 October 1919

Prime Minister: David Lloyd George

Preceded by: The Viscount Grey of Fallodon

Succeeded by: The Earl Curzon of Kedleston

First Lord of the Admiralty

In office: 25 May 1915 – 10 December 1916

Prime Minister: H. H. Asquith; David Lloyd George

Preceded by: Winston Churchill

Succeeded by: Sir Edward Carson

Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal

In office: 11 July 1902 – 17 October 1903

Preceded by: The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Succeeded by: The 4th Marquess of Salisbury

Chief Secretary for Ireland

In office: 7 March 1887 – 9 November 1891

Prime Minister: The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Preceded by: Sir Michael Hicks Beach

Succeeded by: William Jackson

Secretary for Scotland

In office: 5 August 1886 – 11 March 1887

Prime Minister: The 3rd Marquess of Salisbury

Preceded by: The Earl of Dalhousie

Succeeded by: The Marquess of Lothian

Leadership positions: Parliamentary offices

Personal details

Born: Arthur James Balfour, 25 July 1848, Whittingehame House, East Lothian, Scotland

Died: 19 March 1930 (aged 81), Woking, Surrey, England

Resting place: Whittingehame Church, Whittingehame

Nationality: British

Political party: Conservative

Parents: James Maitland Balfour (father)

Alma mater: Trinity College, Cambridge

Occupation: Politician

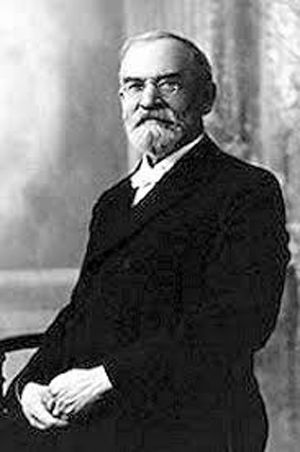

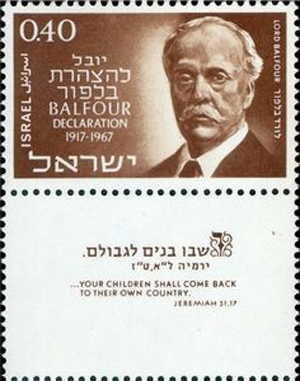

Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour, KG, OM, PC, FRS, FBA, DL (/ˈbælfər, -fɔːr/,[1] traditionally Scottish /bəlˈfʊər/;[2][3] 25 July 1848 – 19 March 1930) was a British Conservative statesman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1902 to 1905. As Foreign Secretary in the Lloyd George ministry, he issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917 on behalf of the cabinet.

Entering Parliament in 1874, Balfour achieved prominence as Chief Secretary for Ireland, in which position he suppressed agrarian unrest whilst taking measures against absentee landlords. He opposed Irish Home Rule, saying there could be no half-way house between Ireland remaining within the United Kingdom or becoming independent. From 1891 he led the Conservative Party in the House of Commons, serving under his uncle, Lord Salisbury, whose government won large majorities in 1895 and 1900. An esteemed debater, he was bored by the mundane tasks of party management.

In July 1902 he succeeded his uncle as Prime Minister. In domestic policy he passed the Irish Land Act 1903, which bought out most of the Anglo-Irish land owners. The Education Act 1902 had a major long-term impact in modernising the school system in England and Wales and provided financial support for schools operated by the Church of England and by the Catholic Church. Nonconformists were outraged and mobilized their voters, but were unable to reverse it. In foreign and defence policy, he oversaw reform of British defence policy and supported Jackie Fisher's naval innovations. He secured the Entente Cordiale with France, an alliance that isolated Germany. He cautiously embraced imperial preference as championed by Joseph Chamberlain, but resignations from the Cabinet over the abandonment of free trade left his party divided. He also suffered from public anger at the later stages of the Boer war (counter-insurgency warfare characterized as "methods of barbarism") and the importation of Chinese labour to South Africa ("Chinese slavery"). He resigned as Prime Minister in December 1905 and the following month the Conservatives suffered a landslide defeat at the 1906 election, in which he lost his own seat. He soon re-entered Parliament and continued to serve as Leader of the Opposition throughout the crisis over Lloyd George's 1909 budget, the narrow loss of two further General Elections in 1910, and the passage of the Parliament Act 1911. He resigned as party leader in 1911.

Balfour returned as First Lord of the Admiralty in Asquith's Coalition Government (1915–16). In December 1916 he became Foreign Secretary in David Lloyd George's coalition. He was frequently left out of the inner workings of foreign policy, although the Balfour Declaration on a Jewish homeland bore his name. He continued to serve in senior positions throughout the 1920s, and died on 19 March 1930 aged 81, having spent a vast inherited fortune. He never married. Balfour trained as a philosopher – he originated an argument against believing that human reason could determine truth – and was seen as having a detached attitude to life, epitomised by a remark attributed to him: "Nothing matters very much and few things matter at all".

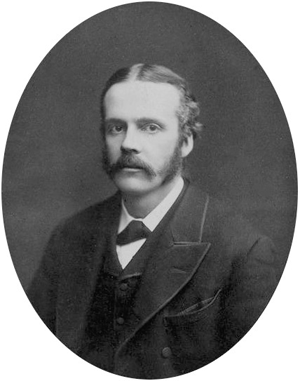

Background and early life Whittingehame House

Whittingehame HouseArthur Balfour was born at Whittingehame House, East Lothian, Scotland, the eldest son of James Maitland Balfour (1820–1856) and Lady Blanche Gascoyne-Cecil (1825–1872). His father was a Scottish MP, as was his grandfather James; his mother, a member of the Cecil family descended from Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, was the daughter of the 2nd Marquess of Salisbury and a sister to the 3rd Marquess, the future Prime Minister.[4] His godfather was the Duke of Wellington, after whom he was named.[5] He was the eldest son, third of eight children, and had four brothers and three sisters. Arthur Balfour was educated at Grange Preparatory School at Hoddesdon, Hertfordshire (1859–1861), and Eton College (1861–1866), where he studied with the influential master, William Johnson Cory. He then went up to the University of Cambridge, where he read moral sciences at Trinity College (1866–1869),[6] graduating with a second-class honours degree. His younger brother was the Cambridge embryologist Francis Maitland Balfour (1851–1882).[7]

Personal lifeBalfour met his cousin May Lyttelton in 1870 when she was 19. After her two previous serious suitors had died, Balfour is said to have declared his love for her in December 1874. She died of typhus on Palm Sunday, March 1875; Balfour arranged for an emerald ring to be buried in her coffin. Lavinia Talbot, May's older sister, believed that an engagement had been imminent, but her recollections of Balfour's distress (he was "staggered") were not written down until thirty years later. The historian R. J. Q. Adams points out that May's letters discuss her love life in detail, but contain no evidence that she was in love with Balfour, nor that he had spoken to her of marriage. He visited her only once during her serious three-month illness, and was soon accepting social invitations again within a month of her death. Adams suggests that, although he may simply have been too shy to express his feelings fully, Balfour may also have encouraged tales of his youthful tragedy as a convenient cover for his disinclination to marry; the matter cannot be conclusively proven.[8]:29–33 In later years mediums claimed to pass on messages from her – see the "Palm Sunday Case".[9][10]

Balfour remained a lifelong bachelor. Margot Tennant (later Margot Asquith) wished to marry him, but Balfour said: "No, that is not so. I rather think of having a career of my own."[5] His household was maintained by his unmarried sister, Alice. In middle age, Balfour had a 40-year friendship with Mary Charteris (née Wyndham), Lady Elcho, later Countess of Wemyss and March.[11] Although one biographer writes that "it is difficult to say how far the relationship went", her letters suggest they may have become lovers in 1887 and may have engaged in sado-masochism,[8]:47 a claim echoed by A. N. Wilson.[10] Another biographer believes they had "no direct physical relationship", although he dismisses as unlikely suggestions that Balfour was homosexual, or, in view of a time during the Boer War when he was seen as he replied to a message while drying himself after his bath, Lord Beaverbrook's claim that he was "a hermaphrodite" whom no-one saw naked.[12]

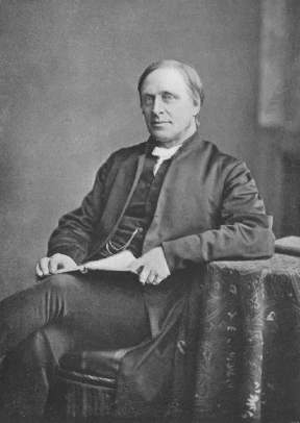

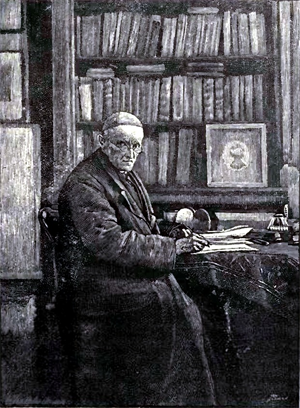

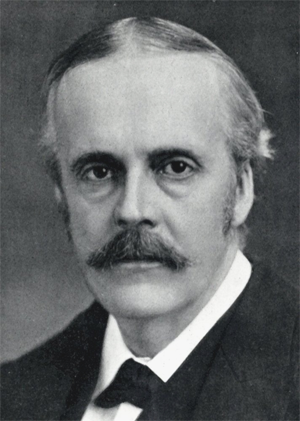

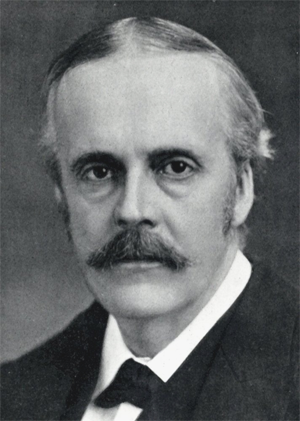

Early career Balfour early in his career

Balfour early in his careerIn 1874 Balfour was elected Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Hertford until 1885. In spring 1878, he became Private Secretary to his uncle, Lord Salisbury. He accompanied Salisbury (then Foreign Secretary) to the Congress of Berlin and gained his first experience in international politics in connection with the settlement of the Russo-Turkish conflict. At the same time he became known in the world of letters; the academic subtlety and literary achievement of his Defence of Philosophic Doubt (1879) suggested he might make a reputation as a philosopher.[13]

Balfour divided his time between politics and academic pursuits. Biographer Sydney Zebel suggested that Belfour continued to appear an amateur or dabbler in public affairs, devoid of ambition and indifferent to policy issues. However, in fact he actually made a dramatic transition to a deeply involved politician. His assets, according to Zebel, included a strong ambition that he kept hidden, shrewd political judgment, a knack for negotiation, a taste for intrigue, and care to avoid factionalism. Most importantly, he deepened his close ties with his uncle Lord Salisbury. He also maintained cordial relationships with Disraeli, Gladstone and other national leaders.[14]:27

Released from his duties as private secretary by the 1880 general election, he began to take more part in parliamentary affairs. He was for a time politically associated with Lord Randolph Churchill, Sir Henry Drummond Wolff and John Gorst. This quartet became known as the "Fourth Party" and gained notoriety for leader Lord Randolph Churchill's free criticism of Sir Stafford Northcote, Lord Cross and other prominent members of the Conservative "old gang".[14]:28–44[15]

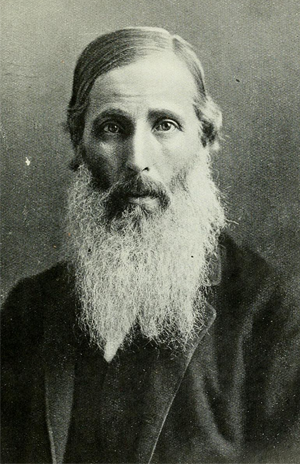

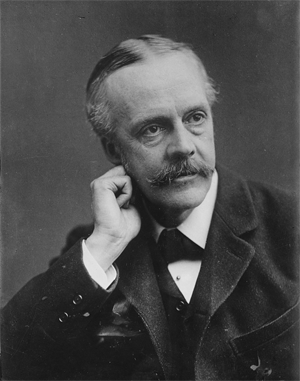

Service in Lord Salisbury's governments Balfour c. 1890

Balfour c. 1890In 1885, Lord Salisbury appointed Balfour President of the Local Government Board; the following year he became Secretary for Scotland with a seat in the cabinet. These offices, while offering few opportunities for distinction, were an apprenticeship. In early 1887, Sir Michael Hicks Beach, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, resigned because of illness and Salisbury appointed his nephew in his place.[16] That surprised the political world and possibly led to the British phrase "Bob's your uncle!"[17] The selection took the political world by surprise, and was much criticized. It was received with contemptuous ridicule by the Irish Nationalists, for none suspected Balfour's immense strength of will, his debating power, his ability in attack and his still greater capacity to disregard criticism.[16] Balfour surprised critics by ruthless enforcement of the Crimes Act, earning the nickname "Bloody Balfour". His steady administration did much to dispel his reputation as a political lightweight.[18]

In Parliament he resisted overtures to the Irish Parliamentary Party on Home Rule, and, allied with Joseph Chamberlain's Liberal Unionists, encouraged Unionist activism in Ireland. Balfour also helped the poor by creating the Congested Districts Board for Ireland in 1890. In 1886–1892 he became one of the most effective public speakers of the age. Impressive in matter rather than delivery, his speeches were logical and convincing, and delighted an ever-wider audience.[16]

On the death of W. H. Smith in 1891, Balfour became First Lord of the Treasury – the last in British history not to have been concurrently Prime Minister as well – and Leader of the House of Commons. After the fall of the government in 1892 he spent three years in opposition. When the Conservatives returned to power, in coalition with the Liberal Unionists, in 1895, Balfour again became Leader of the House and First Lord of the Treasury. His management of the abortive education proposals of 1896 showed a disinclination for the drudgery of parliamentary management, yet he saw the passage of a bill providing Ireland with improved local government under the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 and joined in debates on foreign and domestic questions between 1895 and 1900.[16]

During the illness of Lord Salisbury in 1898, and again in Salisbury's absence abroad, Balfour was in charge of the Foreign Office, and he conducted negotiations with Russia on the question of railways in North China. As a member of the cabinet responsible for the Transvaal negotiations in 1899, he bore his share of controversy and, when the war began disastrously, he was first to realise the need to use the country's full military strength. His leadership of the House was marked by firmness in the suppression of obstruction, yet there was a slight revival of the criticisms of 1896.[16]

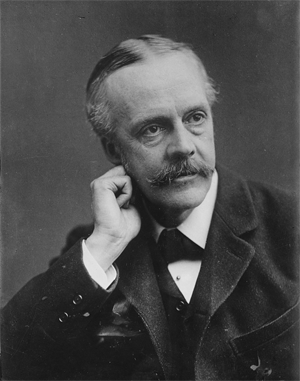

Prime MinisterFurther information: Balfour ministry

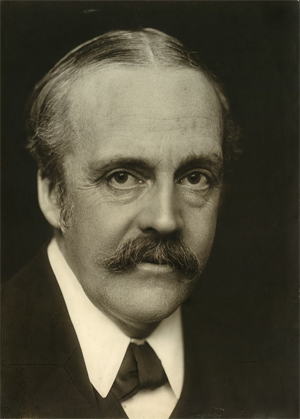

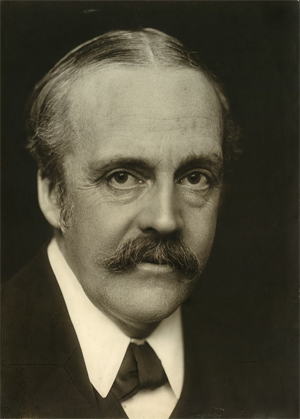

Portrait by George Charles Beresford, 1902

Portrait by George Charles Beresford, 1902With Lord Salisbury's resignation on 11 July 1902, Balfour succeeded him as Prime Minister, with the approval of all the Unionist party. The new Prime Minister came into power practically at the same moment as the coronation of King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra and the end of the South African War. The Liberal party was still disorganised over the Boers.[19]

In foreign affairs, Balfour and his Foreign Secretary, Lord Lansdowne, improved relations with France, culminating in the Entente Cordiale of 1904. The period also saw the Russo-Japanese War, when Britain, an ally of the Japanese, came close to war with Russia after the Dogger Bank incident. On the whole, Balfour left the conduct of foreign policy to Lansdowne, being busy himself with domestic problems.[14]

Balfour, who had known Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann since 1906, opposed Russian mistreatment of Jews and increasingly supported Zionism as a programme for European Jews to settle in Palestine.[20] However, in 1905 he supported the Aliens Act 1905, one of whose main objectives was to control and restrict Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe.[21][22]

The budget was certain to show a surplus and taxation could be remitted. Yet as events proved, it was the budget that would sow dissension, override other legislative concerns and signal a new political movement. Charles Thomson Ritchie's remission of the shilling import-duty on corn led to Joseph Chamberlain's crusade in favour of tariff reform. These were taxes on imported goods with trade preference given to the Empire, to protect British industry from competition, strengthen the Empire in the face of growing German and American economic power, and provide revenue, other than raising taxes, for the social welfare legislation. As the session proceeded, the rift grew in the Unionist ranks.[19] Tariff reform was popular with Unionist supporters, but the threat of higher prices for food imports made the policy an electoral albatross. Hoping to split the difference between the free traders and tariff reformers in his cabinet and party, Balfour favoured retaliatory tariffs to punish others who had tariffs against the British, in the hope of encouraging global free trade. This was not sufficient for either the free traders or the extreme tariff reformers in government. With Balfour's agreement, Chamberlain resigned from the Cabinet in late 1903 to campaign for tariff reform. At the same time, Balfour tried to balance the two factions by accepting the resignation of three free-trading ministers, including Chancellor Ritchie, but the almost simultaneous resignation of the free-trader Duke of Devonshire (who as Lord Hartington had been the Liberal Unionist leader of the 1880s) left Balfour's Cabinet weak. By 1905 few Unionist MPs were still free traders (Winston Churchill crossed to the Liberals in 1904 when threatened with deselection at Oldham), but Balfour's act had drained his authority within the government.[14]

Balfour resigned as Prime Minister in December 1905, hoping the Liberal leader Campbell-Bannerman would be unable to form a strong government. This was dashed when Campbell-Bannerman faced down an attempt ("The Relugas Compact") to "kick him upstairs" to the House of Lords. The Conservatives were defeated by the Liberals at the general election the following January (in terms of MPs, a Liberal landslide), with Balfour losing his seat at Manchester East to Thomas Gardner Horridge, a solicitor and king's counsel. Only 157 Conservatives were returned to the Commons, at least two-thirds followers of Chamberlain, who chaired the Conservative MPs until Balfour won a safe seat in the City of London.[23]

Achievements and mistakesAccording to historian Robert Ensor, writing in 1936, Balfour can be credited with achievement in five major areas:[24]:355

1. The Education Act 1902 (and a similar measure for London in 1903);[25]

2. The Irish Land Purchase Act, 1903 which bought out the Anglo-English land owners;[26][27]

3. The Licensing Act 1904;[28]

4. In military policy, the creation of the Committee of Imperial Defence (1904) and support for Sir John Fisher's naval reforms.

5. In foreign policy, the Anglo-French Convention (1904), which formed the basis of the Entente with France.

The Education Act lasted four decades and eventually was highly praised. Eugene Rasor states, "Balfour was credited and much praised from many perspectives with the success [of the 1902 education act]. His commitment to education was fundamental and strong."[29]:20 At the time it hurt Balfour because the Liberal party used it to rally their Noncomformist supporters. Ensor said the Act ranked:

among the two or three greatest constructive measures of the twentieth century....[He did not write it] but no statesman less dominated than Balfour was by the concept of national efficiency would have taken it up and carried it through, since its cost on the side of votes was obvious and deterrent....Public money was thus made available for the first time to ensure properly paid teachers and a standardized level of efficiency for all children alike [including the Anglican and Catholic schools].[24]:355–56

For most of the 19th century, the very powerful political and economic position of the Church of Ireland (Anglican) landowners blocked the political aspirations of Irish nationalists, who by 1900 included both Catholic and Presbyterian elements. Balfour's solution was to buy them out, not by compulsion, but by offering the owners a full immediate payment and a 12% bonus on the sales price. The British government purchased 13 million acres (53,000 km2) by 1920, and sold farms to the tenants at low payments spread over seven decades. It would cost money, but all sides proved amenable.[24]:358–60 Starting in 1923 the Irish government bought out most of the remaining landowners, and in 1933 diverted payments being made to the British treasury and used them for local improvements.[30]

Balfour's introduction of Chinese coolie labour in South Africa enabled the Liberals to counterattack, charging that his measures amounted to "Chinese slavery".[24]:355, 376–78[31] Likerwise Liberals energized the Nonconformists when they attacked Balfour's Licensing Act 1904 which paid pub owners to close down. In the long-run it did reduce the great oversupply of pubs, while in the short run Balfour's party was hurt.[24]:360–61

Balfour failed to solve his greatest political challenge - the debate over tariffs that ripped his party apart. Chamberlain proposed to turn the Empire into a closed trade bloc protected by high tariffs against imports from Germany and the United States. He argued that tariff reform would revive a flagging British economy, strengthen imperial ties with the dominions and the colonies, and produce a positive programme that would facilitate reelection. He was vehemently opposed by Conservative free traders who denounced the proposal as economically fallacious, and open to the charge of raising food prices in Britain. Balfour tried to forestall disruption by removing key ministers on each side, and offering a much narrower tariff programme. It was ingenious, but both sides rejected any compromise, and his party's chances for reelection were ruined.[32][33]:4–6

Balfour may have been personally sympathetic to extending suffrage, with his brother Gerald, Conservative MP for Leeds Central married to women's suffrage activist Constance Lytton's sister Betty.[34] But he accepted the strength of the political opposition to women's suffrage, as shown in correspondence with Christabel Pankhurst, a leader of the WSPU. Balfour argued that he was 'not convinced the majority of women actually wanted the vote', in 1907. A rebuttal which meant extending the activist campaign for women's rights.[34] He was reminded by Lytton of a speech he made in 1892, namely that this question 'will arise again, menacing and ripe for resolution', she asked him to meet WSPU leader, Christabel Pankhurst, after a series of hunger strikes and suffering by imprisoned suffragettes in 1907. Balfour refused on the grounds of her militancy.[34] Christabel pleaded direct to meet Balfour as Conservative party leader, on their policy manifesto for the General Election of 1909, but he refused again as women's suffrage was 'not a party question and his colleagues were divided on the matter'.[34] She tried and failed again to get his open support in parliament for women's cause in the 1910 private member's Conciliation Bill.[34] He voted for the bill in the end but not for its progress to the Grand Committee, preventing it becoming law, and extending the activist campaigns as a result again.[34] The following year Lytton and Annie Kenney in person after another reading of the Bill, but again it was not prioritised as government business.[34] His sister-in-law Lady Betty Balfour spoke to Churchill that her brother was to speak for this policy, and also met the Prime Minister in a 2011 delegation of the women's movements respresenting the Conservative and Unionist Women's Franchise Association.[34] But it was not until 1918 that (some) women were given the right to vote in elections in the United Kingdom, despite a forty year campaign.[34]

Historians generally praised Balfour's achievements in military and foreign policy. Cannon & Crowcroft 2015 stress the importance of the Anglo‐French Entente of 1904, and the establishment of the Committee of Imperial Defence.[35] Rasor points to twelve historians who have examined his key role in naval and military reforms.[29]:39–40[24]:361–71 However there was little political payback at the time. The local Conservative campaigns in 1906 focused mostly on a few domestic issues.[36] Balfour gave strong support for Jackie Fisher's naval reforms.[37]

Balfour created and chaired the Committee of Imperial Defence, which provided better long-term coordinated planning between the Army and Navy.[38] Austen Chamberlain said Britain would have been unprepared for the World War without his Committee of Imperial Defence. He wrote, "It is impossible to overrate the services thus rendered by Balfour to the Country and Empire....[Without the CID] victory would have been impossible."[39] Historians also praised the Anglo-French Convention (1904), which formed the basis of the Entente Cordiale with France that proved decisive in 1914.[40]

Cabinet of Arthur BalfourThis section is transcluded from Unionist government, 1895–1905. (edit | history)

Balfour was appointed Prime Minister on 12 July 1902 while the King was recovering from his recent appendicitis operation. Changes to the Cabinet were thus not announced until 9 August, when the King was back in London.[41] The new ministers were received in audience and took their oaths on 11 August.

Portfolio / Minister / Took office / Left office / Party

First Lord of the Treasury; Lord Privy Seal; Leader of the House of Commons / Arthur Balfour* / 12 July 1902 / 4 December 1905 / Conservative

Lord Chancellor / The Earl of Halsbury / 29 June 1895 4/ December 1905 / Conservative

Lord President of the Council; Leader of the House of Lords / The Duke of Devonshire / 29 June 1895 / 19 October 1903 / Liberal Unionist

Lord President of the Council / The Marquess of Londonderry / 19 October 1903 / 11 December 1905 / Conservative

Leader of the House of Lords / The Marquess of Lansdowne / 13 October 1903 / 4 December 1905 / Liberal Unionist

Secretary of State for the Home Department / Aretas Akers-Douglas / 12 July 1902 / 5 December 1905 / Conservative

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs / The Marquess of Lansdowne / 12 November 1900 / 4 December 1905 / Liberal Unionist

Secretary of State for the Colonies / Joseph Chamberlain / 29 June 1895 / 16 September 1903 / Liberal Unionist

Secretary of State for the Colonies / Alfred Lyttelton / 11 October 1903 / 4 December 1905 / Liberal Unionist

Secretary of State for War / St John Brodrick / 12 November 1900 / 6 October 1903 / Conservative

Secretary of State for War / H. O. Arnold-Forster / 6 October 1903 / 4 December 1905 / Liberal Unionist

Secretary of State for India / Lord George Hamilton / 4 July 1895 / 9 October 1903 / Conservative

Secretary of State for India / St John Brodrick / 9 October 1903 / 4 December 1905 / Conservative

First Lord of the Admiralty / The Earl of Selborne / 1900 / 1905 / Liberal Unionist

Chancellor of the Exchequer / Charles Ritchie / 11 August 1902 / 9 October 1903 / Conservative

Chancellor of the Exchequer / Austen Chamberlain / 9 October 1903 / 4 December 1905 / Liberal Unionist

President of the Board of Trade / Gerald Balfour / 12 November 1900 / 12 March 1905 / Conservative

President of the Board of Trade / The 4th Marquess of Salisbury / 12 March 1905 / 4 December 1905 / Conservative

Secretary for Scotland / The Lord Balfour of Burleigh / 29 June 1895 / 9 October 1903 / Conservative

Secretary for Scotland / Andrew Murray / 9 October 1903 / 2 February 1905 / Conservative

Secretary for Scotland / The Marquess of Linlithgow / 2 February 1905 / 4 December 1905 / Conservative

Chief Secretary for Ireland / George Wyndham / 9 November 1900 / 12 March 1905 / Conservative

Chief Secretary for Ireland / Walter Long / 12 March 1905 / 4 December 1905 / Conservative

President of the Local Government Board / Walter Long / 1900 / 1905 / Conservative

President of the Local Government Board / Gerald Balfour / 1905 / 11 December 1905 / Conservative

President of the Board of Agriculture / Robert William Hanbury / 16 November 1900 / 28 April 1903 / Conservative

President of the Board of Education / The Marquess of Londonderry / 11 August 1902 / 4 December 1905 / Conservative

Lord Chancellor of Ireland / The Lord Ashbourne / 29 June 1895 / 1905 / Conservative

First Commissioner of Works / The Lord Windsor /11 August 1902 / 4 December 1905 / Conservative

Postmaster General / Austen Chamberlain / 11 August 1902 / 9 October 1903 / Liberal Unionist

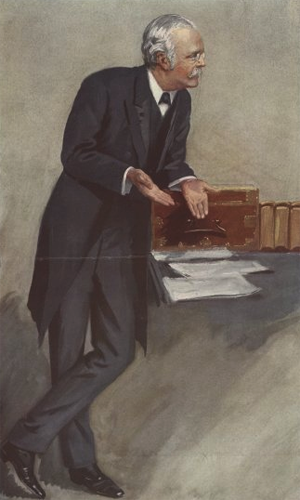

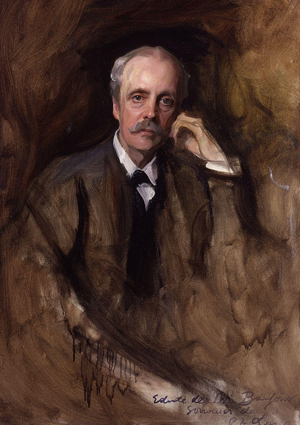

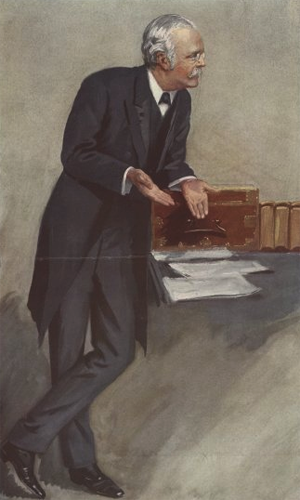

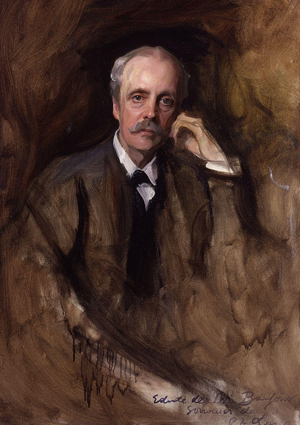

Later career Painting by John Singer Sargent, 1908

Painting by John Singer Sargent, 1908 Balfour caricatured by Vanity Fair, 1910

Balfour caricatured by Vanity Fair, 1910After the general election of 1906 Balfour remained party leader, his position strengthened by Joseph Chamberlain's absence from the House of Commons after his stroke in July 1906, but he was unable to make much headway against the huge Liberal majority in the Commons. An early attempt to score a debating triumph over the government, made in Balfour's usual abstruse, theoretical style, saw Campbell-Bannerman respond with: "Enough of this foolery," to the delight of his supporters. Balfour made the controversial decision, with Lord Lansdowne, to use the heavily Unionist House of Lords as a check on the political programme and legislation of the Liberal party in the Commons. Legislation was vetoed or altered by amendments between 1906 and 1909, leading David Lloyd George to remark that the Lords was "the right hon. Gentleman's poodle. It fetches and carries for him. It barks for him. It bites anybody that he sets it on to. And we are told that this is a great revising Chamber, the safeguard of liberty in the country."[42] The issue was forced by the Liberals with Lloyd George's People's Budget, provoking the constitutional crisis that led to the Parliament Act 1911, which limited the Lords to delaying bills for up to two years. After the Unionists lost the general elections of 1910 (despite softening the tariff reform policy with Balfour's promise of a referendum on food taxes), the Unionist peers split to allow the Parliament Act to pass the House of Lords, to prevent mass creation of Liberal peers by the new King, George V. The exhausted Balfour resigned as party leader after the crisis, and was succeeded in late 1911 by Bonar Law.[14]

Balfour remained important in the party, however, and when the Unionists joined Asquith's coalition government in May 1915, Balfour succeeded Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. When Asquith's government collapsed in December 1916, Balfour, who seemed a potential successor to the premiership, became Foreign Secretary in Lloyd George's new administration, but not in the small War Cabinet, and was frequently left out of inner workings of government. Balfour's service as Foreign Secretary was notable for the Balfour Mission, a crucial alliance-building visit to the US in April 1917, and the Balfour Declaration of 1917, a letter to Lord Rothschild affirming the government's support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then part of the Ottoman Empire.[43]

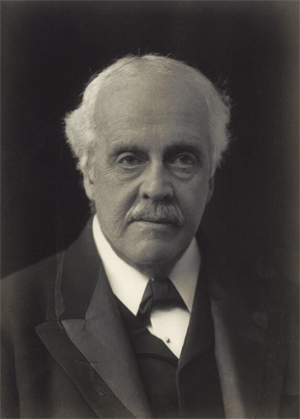

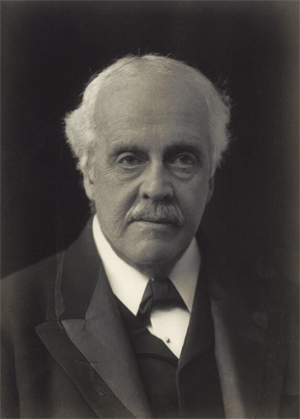

Portrait by Walter Stoneman, 1921

Portrait by Walter Stoneman, 1921Balfour resigned as Foreign Secretary following the Versailles Conference in 1919, but continued in the government (and the Cabinet after normal peacetime political arrangements resumed) as Lord President of the Council. In 1921–22 he represented the British Empire at the Washington Naval Conference and during summer 1922 stood in for the Foreign Secretary, Lord Curzon, who was ill. He put forward a proposal for the international settlement of war debts and reparations (the Balfour Note), but it was not accepted.[14]

On 5 May 1922, Balfour was created Earl of Balfour and Viscount Traprain, of Whittingehame, in the county of Haddington.[44] In October 1922 he, with most of the Conservative leadership, resigned with Lloyd George's government following the Carlton Club meeting, a Conservative back-bench revolt against continuance of the coalition. Bonar Law became Prime Minister. Like many Coalition leaders, he did not hold office in the Conservative governments of 1922–1924, but as an elder statesman, he was consulted by the King in the choice of Stanley Baldwin as Bonar Law's successor as Conservative leader in May 1923. When asked whether "dear George" (the much more experienced Lord Curzon) would be chosen, he replied, referring to Curzon's wealthy wife Grace, "No, dear, George will not but while he may have lost the hope of glory he still possesses the means of Grace."

Balfour was not initially included in Baldwin's second government in 1924, but in 1925, he returned to the Cabinet, in place of the late Lord Curzon as Lord President of the Council, until the government ended in 1929. With 28 years of government service, Balfour had one of the longest ministerial careers in modern British politics, second only to Winston Churchill .[45]

Last yearsBalfour had generally good health until 1928 and remained until then a regular tennis player. Four years previously he had been the first president of the International Lawn Tennis Club of Great Britain. At the end of 1928, most of his teeth were removed and he suffered the unremitting circulatory trouble which ended his life. Before that, he had suffered occasional phlebitis and, by late 1929, he was immobilised by it. Balfour died at his brother Gerald's home, Fishers Hill House in Hook Heath, Woking, on 19 March 1930. At his request a public funeral was declined, and he was buried on 22 March beside members of his family at Whittingehame in a Church of Scotland service although he also belonged to the Church of England. By special remainder, his title passed to his brother Gerald.

His obituaries in The Times, The Guardian and the Daily Herald did not mention the declaration for which he is most famous outside Britain.[46]

Personality Portrait by Philip de László, c. 1931

Portrait by Philip de László, c. 1931Early in Balfour's career he was thought to be merely amusing himself with politics, and it was regarded as doubtful whether his health could withstand the severity of English winters. He was considered a dilettante by his colleagues; regardless, Lord Salisbury gave increasingly powerful posts in his government to his nephew.[16]

Beatrice Webb wrote in her diary:

A man of extraordinary grace of mind and body, delighting in all that is beautiful and distinguished––music, literature, philosophy, religious feeling and moral disinterestedness, aloof from all the greed and crying of common human nature. But a strange paradox as Prime Minister of a great empire! I doubt whether even foreign affairs interest him. For all economic and social questions I gather he has an utter loathing, while the machinery of government and administration would seem to him a disagreeable irrelevance.[47]

Balfour developed a manner known to friends as the Balfourian manner. Edward Harold Begbie, a journalist, attacked him for his self-obsession:

This Balfourian manner...an attitude of mind—an attitude of convinced superiority which insists in the first place on complete detachment from the enthusiasms of the human race, and in the second place on keeping the vulgar world at arm's length....To Mr. Arthur Balfour this studied attitude of aloofness has been fatal, both to his character and to his career. He has said nothing, written nothing, done nothing, which lives in the heart of his countrymen....the charming, gracious, and cultured Mr. Balfour is the most egotistical of men, and a man who would make almost any sacrifice to remain in office.[48]

However, Graham Goodlad argued to the contrary:

Balfour's air of detachment was a pose. He was sincere in his conservatism, mistrusting radical political and social change and believing deeply in the Union with Ireland, the Empire and the superiority of the British race....Those who dismissed him as a languid dilettante were wide of the mark. As Chief Secretary for Ireland from 1887 to 1891 he manifested an unflinching commitment to the maintenance of British authority in the face of popular protest. He combined a strong emphasis on law and order with measures aimed at reforming the landowning system and developing Ireland's backward rural economy.[32]

Churchill compared Balfour to H. H. Asquith: "The difference between Balfour and Asquith is that Arthur is wicked and moral, while Asquith is good and immoral." Balfour said of himself, "I am more or less happy when being praised, not very comfortable when being abused, but I have moments of uneasiness when being explained."[49]

Balfour was interested in the study of dialects and donated money to Joseph Wright's work on the English Dialect Dictionary. Wright wrote in the preface to the first volume that the project would have been "in vain" had he not received the donation from Balfour.[50]

Arthur Balfour was a fan of football and supported Manchester City F.C.[51]

Writings and academic achievementsAs a philosopher, Balfour formulated the basis for the evolutionary argument against naturalism. Balfour argued the Darwinian premise of selection for reproductive fitness cast doubt on scientific naturalism, because human cognitive facilities that would accurately perceive truth could be less advantageous than adaptation for evolutionarily useful illusions.[52]

As he says:

[There is] no distinction to be drawn between the development of reason and that of any other faculty, physiological or psychical, by which the interests of the individual or the race are promoted. From the humblest form of nervous irritation at the one end of the scale, to the reasoning capacity of the most advanced races at the other, everything without exception (sensation, instinct, desire, volition) has been produced directly or indirectly, by natural causes acting for the most part on strictly utilitarian principles. Convenience, not knowledge, therefore, has been the main end to which this process has tended.

— Arthur Balfour[53]

He was a member of the Society for Psychical Research, a society studying psychic and paranormal phenomena, and was its president from 1892 to 1894.[54] In 1914, he delivered the Gifford Lectures at the University of Glasgow,[55] which formed the basis for his book Theism and Humanism (1915).[56]

ArtisticAfter the First World War, when there was controversy over the style of headstone proposed for use on British war graves being taken on by the Imperial War Graves Commission, Balfour submitted a design for a cruciform headstone.[57] At an exhibition in August 1919, it drew many criticisms; the Commission's principal architect, Sir John Burnet, said Balfour's cross would create a criss-cross effect destroying any sense of "restful diginity", Edwin Lutyens called it "extraordinarily ugly", and its shape was variously described as resembling a shooting target or bottle.[57] His design was not accepted but the Commission offered him a second chance to submit another design which he did not take up, having been refused once.[57]:49 After a further exhibition in the House of Commons, the "Balfour cross" was ultimately rejected in favour of the standard headstone the Commission permanently adopted because the latter offered more space for inscriptions and service emblems.[57]:50

Popular cultureBalfour occasionally appears in popular culture.[29]

• Balfour was the subject of two parody novels based on Alice in Wonderland, Clara in Blunderland (1902) and Lost in Blunderland (1903), which appeared under the pseudonym Caroline Lewis; one of the co-authors was Harold Begbie.[58][59]

• The character Arthur Balfour plays a supporting, off-screen role in Upstairs, Downstairs, promoting the family patriarch, Richard Bellamy, to the position of Civil Lord of the Admiralty.

• Balfour was portrayed by Adrian Ropes in the 1974 Thames TV production Jennie: Lady Randolph Churchill.

• Balfour was portrayed by Lyndon Brook in the 1975 ATV production Edward the Seventh.

• A fictionalised version of Arthur Balfour (identified as "Mr. Balfour") appears as British Prime Minister in the science fiction romance The Angel of the Revolution by George Griffith, published in 1893 (when Balfour was still in opposition) but set in an imagined near future of 1903–1905.

• The indecisive Balfour (identified as "Halfan Halfour") appears in "Ministers of Grace", a satirical short story by Saki in which he, and other leading politicians including Quinston, are changed into animals appropriate to their characters.

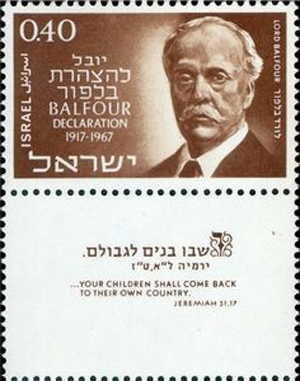

Legacy 1967 Israel stamp commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration

1967 Israel stamp commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Balfour DeclarationA portrait of Balfour by Philip de Laszlo is in the collection of Trinity College, Cambridge.[60]

Balfouria, a moshav in Israel and many streets in Israel are named after him. The town of Balfour, Mpumalanga in South Africa was named after him.[61]

The Lord Balfour Hotel, an Art Deco hotel on Ocean Drive in the South Beach neighborhood of Miami Beach, Florida, is named after him.

Honours and decorations Coat of arms of the Lord Balfour KG, as displayed on his Garter stall plate at St. George's Chapel, Windsor, viz.' Argent on a chevron engrailed between three mullets sable, three otters' heads erased of the field.

Coat of arms of the Lord Balfour KG, as displayed on his Garter stall plate at St. George's Chapel, Windsor, viz.' Argent on a chevron engrailed between three mullets sable, three otters' heads erased of the field.• He was appointed as a Deputy Lieutenant of Ross-shire on 10 September 1880, giving him the post-nominal letters "DL".[62]

• He was sworn of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom in 1885, giving him the style "The Right Honourable" and after ennoblement the post-nominal letters "PC" for life.[63]

• On 3 June 1916 he was appointed to the Order of Merit, giving him the post-nominal letters "OM" for life.[63]

• In 1919, he was elected Chancellor of his old university, Cambridge, in succession to his brother-in-law, Lord Rayleigh.

• He was made a Knight Companion of the Order of the Garter on 24 February 1922, becoming Sir Arthur Balfour and giving him the post-nominal letters "KG" for life.[63]

• On 5 May 1922, Balfour was raised to the peerage as Earl of Balfour and Viscount Thaprain, of Whittingehame, in the county of Haddington. This allowed him to sit in the House of Lords.[63]

• He was awarded the Estonian Cross of Liberty (conferred between 1919–25), third grade, first class, for Civilian Service.

He was given the Freedom of the City/Freedom of the Borough of

• 28 September 1899: Dundee

• 20 September 1902: Haddington, East Lothian[64]

• 19 October 1905: Edinburgh

Honorary degreesCountry / Date / School / Degree

England / 1909 / University of Liverpool / Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[65]

England / 1912 / University of Sheffield / Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[66]

Ontario / 1917 / University of Toronto / Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[67]

Wales / 1921 / University of Wales / Doctor of Letters (D. Litt)

England / 1924 / University of Leeds / Doctor of Laws (LL.D)[68]

This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

See also• Biography portal

• Balfour Declaration

• Balfour Declaration of 1926

• Palm Sunday Case

Notes1. Oxford Dictionaries Oxford Dictionaries Online

2. Taylor, Simon; Márkus, Gilbert (2008). The Place-Names of Fife. Volume Two: Central Fife between the Rivers Leven and Eden. Donington. p. 408.

3. "Balfour". Fife Place-name Data. Glasgow University. n.d. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

4. Chisholm 1911, p. 250.

5. Tuchman, Barbara (1966). The Proud Tower. Macmillan. p. 46.

6. "Balfour, Arthur (BLFR866AJ)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

7.

http://www.burkespeerage.com8. Adams, Ralph James Q. (2007). Balfour: The Last Grandee. John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5424-7.

9. Oppenheim, Janet (1988). The Other World: Spiritualism and Psychical Research in England, 1850–1914. Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-521-34767-9.

10. Wilson, A. N. (2011). The Victorians. Random House. p. 530. ISBN 978-1-4464-9320-5.

11. Sargent, John Singer (February 2010) [1899]. "The Wyndham Sisters: Lady Elcho, Mrs. Adeane, and Mrs. Tennant". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

12. Mackay, Ruddock F. (1985). Balfour, Intellectual Statesman. Oxford University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-19-212245-2.

13. Chisholm 1911, pp. 250–251.

14. Zebel, Sydney Henry (1973). Balfour: A Political Biography. Cambridge: University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-08536-6.

15. Green, Ewen (2006). Balfour. Haus Publishing. pp. 22–. ISBN 978-1-912208-37-1.

16. Chisholm 1911, p. 251.

17. Langguth, A. J. (1981). Saki, a life of Hector Hugh Munro : with six short stories never before collected. Saki, 1870–1916. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 65. ISBN 9780671247157. OCLC 7554446.

18. Massie, Robert (1991). Dreadnought. New York: Random House. pp. 318–319..

19. Chisholm 1911, p. 252.

20. Viorst, Milton (2016). Zionism: The Birth and Transformation of an Ideal. p. 80. ISBN 9781466890329.

21. Sand, Shlomo (2012). The Invention of the Land of Israel: From Holy Land to Homeland. London: Verso. pp. 14–15.

22. Sabbagh, Karl (2006). Palestine : a personal history. London: Atlantic. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-84354-344-2. Balfour warned the House of Commons in his speech of 'the undoubted evils that had fallen upon the country from an immigration which was largely Jewish'

23. Chisholm 1911, p. 254.

24. Ensor, R. C. K. (1936). England, 1870–1914. Oxford: Clarendon.

25. Robinson, Wendy (2002). "Historiographical reflections on the 1902 Education Act". Oxford Review of Education. 28 (2–3): 159–172. doi:10.1080/03054980220143342. JSTOR 1050905.

26. Bull, Philip (2016). "The significance of the nationalist response to the Irish land act of 1903". Irish Historical Studies. 28 (111): 283–305. doi:10.1017/S0021121400011056. ISSN 0021-1214.

27. Bastable, Charles F. (1903). "The Irish Land Purchase Act of 1903". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 18 (1): 1–21. doi:10.2307/1882773. JSTOR 1882773.

28. Jennings, Paul (2009). "Liquor licensing and the local historian: the 1904 Licensing Act and its administration" (PDF). The Local Historian. 9 (1): 24–37.

29. Rasor, Eugene L. (1998). Arthur James Balfour, 1848-1930: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Greenwood. ISBN 9780313288777.

30. Lee, J. J. (1989). Ireland 1912-1985: politics and society. p. 71.

31. Spencer, Scott C. (2014). "'British Liberty Stained:' Chinese Slavery, Imperial Rhetoric, and the 1906 British General Election". Madison Historical Review. 7 (1): 3–.

32. Goodlad, Graham (2010). "Balfour: Graham Goodlad Reviews the Career of AJ Balfour, an Unsuccessful Prime Minister and Party Leader but an Important and Long-Serving Figure on the British Political Scene". History Review. 68: 22–24.

33. Pearce, Robert; Goodlad, Graham (2013). British Prime Ministers From Balfour to Brown.

34. Atkinson, Diane (2018). Rise up, women! : the remarkable lives of the suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 8, 76–77, 137, 169, 184, 201, 209, 253, 267. ISBN 9781408844045. OCLC 1016848621.

35. Adams 2002, p. 199.

36. Russell, A.K. (1973). Liberal landslide: the general election of 1906. p. 92.

37. French, David (1994). "Defending the Empire: The Conservative Party and British Defense Policy, 1899-1915". English Historical Review. 109 (434): 1324–1326.

38. Mackintosh, John P. (1962). "The role of the Committee of Imperial Defence before 1914". English Historical Review. 77 (304): 490–503. JSTOR 561324.

39. Young, Kenneth (1975). "Arthur James Balfour". In Van Thal, Herbert (ed.). The Prime Ministers: From Sir Robert Walpole to Edward Heath. 2. Stein and Day. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-04-942131-8.

40. MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War that Ended Peace: How Europe abandoned peace for the First World War. Profile. pp. 169–171. ISBN 978-1-84765-416-8.

41. "Mr Balfour´s Ministry – full list of appointments". The Times (36842). London. 9 August 1902. p. 5.

42. "HC Deb 26 June 1907 vol 176 cc1408-523". Hansard. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

43. Schneer, Jonathan (2010). The Balfour Declaration: the origins of the Arab-Israeli conflict. Bond Street Books.

44. "No. 32691". The London Gazette. 5 May 1922. p. 3512.

45. Parkinson, Justin (13 June 2013). "Chasing Churchill: Ken Clarke climbs ministerial long-service chart". BBC News.

46. Teveth, Shabtai (1985). Ben-Gurion and the Palestinian Arabs. From Peace to War. p. 106.

47. MacKenzie, Jeanne, ed. (1983). The Diary of Beatrice Webb. Virago. p. 288. ISBN 9780860682103.

48. Begbie, Harold (1920). Mirrors of Downing Street. pp. 76–79.

49. Anon (n.d.). "History of Arthur James Balfour". gov.uk. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

50. Wright, Joseph (1898). The English Dialect Dictionary, Volume 1 A-C. London: Henry Frowde. p. viii.

51. Sanders, Richard (2010). Beastly Fury: The Strange Birth of British Football. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-55381-935-9. p219

52. Gray, John (2011). The Immortalization Commission.

53. Balfour 1915, p. 68.

54. Lycett, Andrew (2008). The Man Who Created Sherlock Holmes. New York: Simon and Schuster. p. 427. ISBN 9780743275255.

55. Theism and Humanism: Being the Gifford Lectures Delivered at the University of Glasgow, 1914. Hodder and Stoughton, George H. Doran Company. 1915.

56. Madigan, Tim (2010). "The Paradoxes of Arthur Balfour". Philosophy Now.

57. Longworth, Philip (1985). The unending vigil: a history of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, 1917-1984. Leo Cooper in association with Secker & Warburg.

58. Sigler, Carolyn, ed. (1997). Alternative Alices: Visions and Revisions of Lewis Carroll's "Alice" Books. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 340–347.

59. Dickinson, Evelyn (20 June 1902). "Literary Note and Books of the Month". United Australia. II (12).

60. "Trinity College, University of Cambridge". BBC Your Paintings. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014.

61. Raper, P. E. (1989). Dictionary of Southern African Place Names. Jonathan Ball Publishers. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-947464-04-2 – via Internet Archive.

62. "The London Gazette". Retrieved 24 July 2016.

63. "Page 1643". The Peerage. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

64. "Mr. Balfour at Haddington". The Times (36879). London. 22 September 1902. p. 5.

65. "Honorary Graduates of the University" (PDF). University of Liverpool. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

66. "Honorary Graduates" (PDF). University of Sheffield. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

67. "University of Toronto Honorary Degree Recipients 1850 - 2016" (PDF). University of Toronto. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

68. "Honour for Earl of Balfour". The Scotsman (25, 446). 17 December 1924. p. 8 – via British Newspaper Archive.

69. Davies, Edward J. (2013). "The Balfours of Balbirnie and Whittingehame". The Scottish Genealogist(60): 84–90.

References• Adams, R.J.Q. (2002). Ramsden, John (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century British Politics.

• Cannon, John; Crowcroft, Robert, eds. (2015). A Dictionary of British History (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

• Torrance, David, The Scottish Secretaries (Birlinn Limited 2006)

• Chisholm, Hugh (1911). "Balfour, Arthur James" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 250–254. This article was written by Chisholm himself soon after Balfour's premiership, while he was still leader of the Opposition. It includes a significant amount of contemporaneous analysis, some of which is summarised here.

Further reading

Biographical• Adams, R. J. Q.: Balfour: The Last Grandee, John Murray, 2007

• Brendon, Piers: Eminent Edwardians (1980) ch 1

• Buckle, George Earle (1922). "Balfour, Arthur James" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 30 (12th ed.). London & New York. pp. 366–368.

• Dugdale, Blanche: Arthur James Balfour, First Earl of Balfour KG, OM, FRS- Volume 1, (1936); Arthur James Balfour, First Earl of Balfour KG, OM, FRS- Volume 2- 1906–1930, (1936), official life by his niece; vol 1 and 2 online free

• Egremont, Max: A life of Arthur James Balfour, William Collins and Company Ltd, 1980

• Green, E. H. H. Balfour (20 British Prime Ministers of the 20th Century); Haus, 2006. ISBN 1-904950-55-8

• Mackay, Ruddock F.: "Balfour, Intellectual Statesman", Oxford 1985 ISBN 0-19-212245-2

• Mackay, Ruddock F., and H. C. G. Matthew. "Balfour, Arthur James, first earl of Balfour (1848–1930)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 accessed 19 Nov 2016 18,000 word scholarly biography

• Pearce, Robert and Graham Goodlad. British Prime Ministers From Balfour to Brown (2013) pp 1–11.

• Raymond, E. T. (1920). A Life of Arthur James Balfour. Little, Brown. p. 1.

• Young, Kenneth: Arthur James Balfour: The happy life of the Politician, Prime Minister, Statesman and Philosopher- 1848–1930, G. Bell and Sons, 1963

• Zebel, Sydney Henry. Balfour: a political biography (ICON Group International, 1973

Specialty studies• Ellenberger, Nancy W. Balfour's World: Aristocracy and Political Culture at the Fin de Siècle (2015). excerpt

• Gollin, Alfred M. Balfour's burden: Arthur Balfour and imperial preference(1965).

• Halévy, Élie (1926) Imperialism And The Rise Of Labour (1926) online

• Halévy, Élie (1956) A History Of The English People: Epilogue vol 1: 1895-1905 ' (1929) online as prime minister pp 131ff,.

• Jacyna, Leon Stephen. "Science and social order in the thought of A.J. Balfour." Isis (1980): 11–34. in JSTOR

• Judd, Denis. Balfour and the British Empire: a study in Imperial evolution 1874–1932 (1968).

• Marriott, J. A. R. Modern England, 1885–1945 (1948), pp. 180–99, on Balfour as Prime Minister. online

• Massie, Robert K. Dreadnought: Britain, Germany, and the Coming of the Great War (1992) pp 310–519, a popular account of Balfour's foreign and naval policies as prime minister.

• Mathew, William M. "The Balfour Declaration and the Palestine Mandate, 1917–1923: British Imperialist Imperatives." British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies 40.3 (2013): 231–250.

• O'Callaghan, Margaret. British high politics and a nationalist Ireland: criminality, land and the law under Forster and Balfour (Cork Univ Pr, 1994).

• Ramsden, John. A History of the Conservative Party: The age of Balfour and Baldwin, 1902–1940 (1978); vol 3 of a scholarly history of the Conservative Party.

• Rempel, Richard A. Unionists Divided; Arthur Balfour, Joseph Chamberlain and the Unionist Free Traders (1972).

• Rofe, J. Simon, and Alan Tomlinson. "Strenuous competition on the field of play, diplomacy off it: the 1908 London Olympics, Theodore Roosevelt and Arthur Balfour, and transatlantic relations." Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 15.1 (2016): 60-79. online

• Shannon, Catherine B. "The Legacy of Arthur Balfour to Twentieth-Century Ireland." in Peter Collins, ed. Nationalism and Unionism (1994): 17–34.

• Shannon, Catherine B. Arthur J. Balfour and Ireland, 1874–1922 (Catholic Univ of America Press, 1988).

• Sugawara, Takeshi. "Arthur Balfour and the Japanese Military Assistance during the Great War." International Relations 2012.168 (2012): pp 44–57. online

• Taylor, Tony. "Arthur Balfour and educational change: The myth revisited." British Journal of Educational Studies 42#2 (1994): 133–149.

• Tomes, Jason. Balfour and foreign policy: the international thought of a conservative statesman (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

• Tuchman, Barbara W.: The Proud Tower – A Portrait of the World Before the War (1966)

Historiography• Loades David, ed. Reader's Guide to British History (2003) 1:122–24; cover major politicians and issues

• Rasor Eugene L. Arthur James Balfour, 1848–1930: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography (1998)

Primary sources• Balfour, Arthur James. Criticism and Beauty: A Lecture Rewritten, Being the Romanes Lecture for 1909 (Oxford, 1910) online

• Cecil, Robert, and Arthur J. Balfour. Salisbury-Balfour Correspondence: Letters Exchanged Between the 3. Marquess of Salisbury and His Nephew Arthur James Balfour; 1869-1892 (Hertfordshire Record Society, 1988).

• Ridley, Jane, and Clayre Percy, erds. The Letters of Arthur Balfour and Lady Elcho 1885–1917. (Hamish Hamilton, 1992).

• Short, Wilfrid M., ed. Arthur James Balfour as Philosopher and Thinker: A Collection of the More Important and Interesting Passages in His Non-political Writings, Speeches, and Addresses, 1879-1912 (1912). online