Part 2 of 2

Philosophy of religion Excerpt

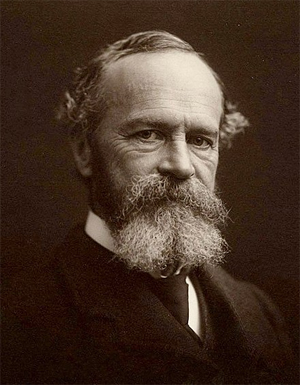

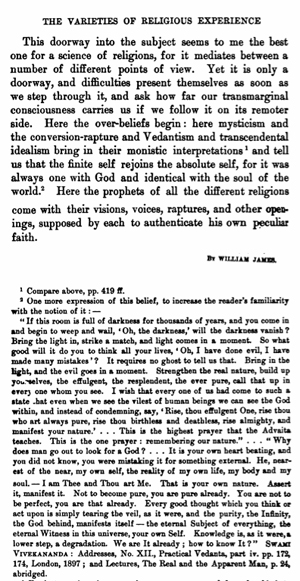

ExcerptJames did important work in philosophy of religion. In his Gifford Lectures at the University of Edinburgh he provided a wide-ranging account of The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) and interpreted them according to his pragmatic leanings. Some of the important claims he makes in this regard:

• Religious genius (experience) should be the primary topic in the study of religion, rather than religious institutions—since institutions are merely the social descendant of genius.

• The intense, even pathological varieties of experience (religious or otherwise) should be sought by psychologists, because they represent the closest thing to a microscope of the mind—that is, they show us in drastically enlarged form the normal processes of things.

• In order to usefully interpret the realm of common, shared experience and history, we must each make certain "over-beliefs" in things which, while they cannot be proven on the basis of experience, help us to live fuller and better lives.

• Religious Mysticism is only one half of mysticism, the other half is composed of the insane and both of these are co-located in the 'great subliminal or transmarginal region'.[54]

James investigated mystical experiences throughout his life, leading him to experiment with chloral hydrate (1870), amyl nitrite (1875), nitrous oxide (1882), and peyote (1896).[citation needed] James claimed that it was only when he was under the influence of nitrous oxide that he was able to understand Hegel.[55] He concluded that while the revelations of the mystic hold true, they hold true only for the mystic; for others, they are certainly ideas to be considered, but can hold no claim to truth without personal experience of such. American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia classes him as one of several figures who "took a more pantheist or pandeist approach by rejecting views of God as separate from the world."[56]

MysticismWilliam James provided a description of the mystical experience, in his famous collection of lectures published in 1902 as The Varieties of Religious Experience.[57] These criteria are as follows

• Passivity – a feeling of being grasped and held by a superior power not under your own control.

• Ineffability – no adequate way to use human language to describe the experience.

• Noetic – universal truths revealed that are unable to be acquired anywhere else.

• Transient – the mystical experience is only a temporary experience.

InstinctsSee also: Instinct

Like Sigmund Freud, James was influenced by Charles Darwin's theory of natural selection.[58] At the core of James' theory of psychology, as defined in The Principles of Psychology (1890), was a system of "instincts". James wrote that humans had many instincts, even more than other animals.[58] These instincts, he said, could be overridden by experience and by each other, as many of the instincts were actually in conflict with each other.[58] In the 1920s, however, psychology turned away from evolutionary theory and embraced radical behaviorism.[58]

Theory of emotionJames is one of the two namesakes of the James–Lange theory of emotion, which he formulated independently of Carl Lange in the 1880s. The theory holds that emotion is the mind's perception of physiological conditions that result from some stimulus. In James's oft-cited example, it is not that we see a bear, fear it, and run; we see a bear and run; consequently, we fear the bear. Our mind's perception of the higher adrenaline level, heartbeat, etc. is the emotion.

This way of thinking about emotion has great consequences for the philosophy of aesthetics as well as to the philosophy and practice of education.[59] Here is a passage from his work, The Principles of Psychology, that spells out those consequences:

[W]e must immediately insist that aesthetic emotion, pure and simple, the pleasure given us by certain lines and masses, and combinations of colors and sounds, is an absolutely sensational experience, an optical or auricular feeling that is primary, and not due to the repercussion backwards of other sensations elsewhere consecutively aroused. To this simple primary and immediate pleasure in certain pure sensations and harmonious combinations of them, there may, it is true, be added secondary pleasures; and in the practical enjoyment of works of art by the masses of mankind these secondary pleasures play a great part. The more classic one's taste is, however, the less relatively important are the secondary pleasures felt to be, in comparison with those of the primary sensation as it comes in. Classicism and romanticism have their battles over this point.

The theory of emotion was also independently developed in Italy by the anthropologist Giuseppe Sergi.[60][61]

William James' bearFrom Joseph LeDoux's description of William James's Emotion:[62]

Why do we run away if we notice that we are in danger? Because we are afraid of what will happen if we don't. This obvious answer to a seemingly trivial question has been the central concern of a century-old debate about the nature of our emotions.

It all began in 1884 when William James published an article titled "What Is an Emotion?"[63] The article appeared in a philosophy journal called Mind, as there were no psychology journals yet. It was important, not because it definitively answered the question it raised, but because of the way in which James phrased his response. He conceived of an emotion in terms of a sequence of events that starts with the occurrence of an arousing stimulus (the sympathetic nervous system or the parasympathetic nervous system); and ends with a passionate feeling, a conscious emotional experience. A major goal of emotion research is still to elucidate this stimulus-to-feeling sequence—to figure out what processes come between the stimulus and the feeling.

James set out to answer his question by asking another: do we run from a bear because we are afraid or are we afraid because we run? He proposed that the obvious answer, that we run because we are afraid, was wrong, and instead argued that we are afraid because we run:

Our natural way of thinking about…emotions is that the mental perception of some fact excites the mental affection called emotion, and that this latter state of mind gives rise to the bodily expression. My theory, on the contrary, is that the bodily changes follow directly the perception of the exciting fact, and that our feeling of the same changes as they occur IS the emotion (called 'feeling' by Damasio).

The essence of James's proposal was simple. It was premised on the fact that emotions are often accompanied by bodily responses (racing heart, tight stomach, sweaty palms, tense muscles, and so on; sympathetic nervous system) and that we can sense what is going on inside our body much the same as we can sense what is going on in the outside world. According to James, emotions feel different from other states of mind because they have these bodily responses that give rise to internal sensations, and different emotions feel different from one another because they are accompanied by different bodily responses and sensations. For example, when we see James's bear, we run away. During this act of escape, the body goes through a physiological upheaval: blood pressure rises, heart rate increases, pupils dilate, palms sweat, muscles contract in certain ways (evolutionary, innate defense mechanisms). Other kinds of emotional situations will result in different bodily upheavals. In each case, the physiological responses return to the brain in the form of bodily sensations, and the unique pattern of sensory feedback gives each emotion its unique quality. Fear feels different from anger or love because it has a different physiological signature (the parasympathetic nervous system for love). The mental aspect of emotion, the feeling, is a slave to its physiology, not vice versa: we do not tremble because we are afraid or cry because we feel sad; we are afraid because we tremble and are sad because we cry.

Philosophy of historyOne of the long-standing schisms in the philosophy of history concerns the role of individuals in social change.

One faction sees individuals (as seen in Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities and Thomas Carlyle's The French Revolution, A History) as the motive power of history, and the broader society as the page on which they write their acts. The other sees society as moving according to holistic principles or laws, and sees individuals as its more-or-less willing pawns. In 1880, James waded into this controversy with "Great Men, Great Thoughts, and the Environment", an essay published in the Atlantic Monthly. He took Carlyle's side, but without Carlyle's one-sided emphasis on the political/military sphere, upon heroes as the founders or overthrowers of states and empires.

A philosopher, according to James, must accept geniuses as a given entity the same way as a biologist accepts as an entity Darwin's "spontaneous variations". The role of an individual will depend on the degree of its conformity with the social environment, epoch, moment, etc.[64]

James introduces a notion of receptivities of the moment. The societal mutations from generation to generation are determined (directly or indirectly) mainly by the acts or examples of individuals whose genius was so adapted to the receptivities of the moment or whose accidental position of authority was so critical that they became ferments, initiators of movements, setters of precedent or fashion, centers of corruption, or destroyers of other persons, whose gifts, had they had free play, would have led society in another direction.[65]

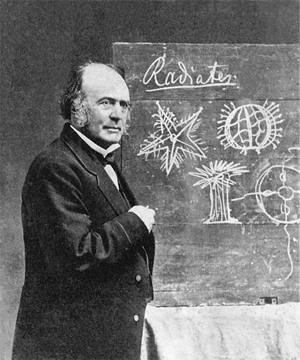

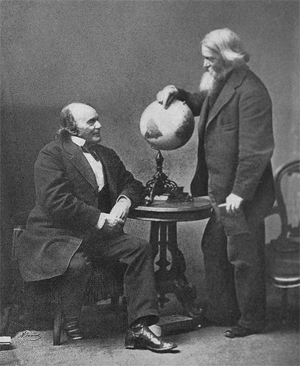

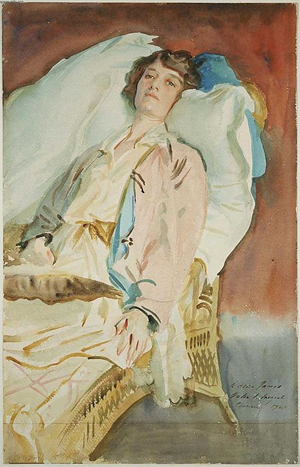

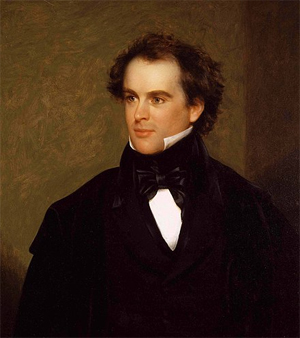

View on spiritualism and associationism James in a séance with a spiritualist medium

James in a séance with a spiritualist mediumJames studied closely the schools of thought known as associationism and spiritualism. The view of an associationist is that each experience that one has leads to another, creating a chain of events. The association does not tie together two ideas, but rather physical objects.[66] This association occurs on an atomic level. Small physical changes occur in the brain which eventually form complex ideas or associations. Thoughts are formed as these complex ideas work together and lead to new experiences. Isaac Newton and David Hartley both were precursors to this school of thought, proposing such ideas as "physical vibrations in the brain, spinal cord, and nerves are the basis of all sensations, all ideas, and all motions…"[67] James disagreed with associationism in that he believed it to be too simple. He referred to associationism as "psychology without a soul"[68] because there is nothing from within creating ideas; they just arise by associating objects with one another.

On the other hand, a spiritualist believes that mental events are attributed to the soul. Whereas in associationism, ideas and behaviors are separate, in spiritualism, they are connected. Spiritualism encompasses the term innatism, which suggests that ideas cause behavior. Ideas of past behavior influence the way a person will act in the future; these ideas are all tied together by the soul. Therefore, an inner soul causes one to have a thought, which leads them to perform a behavior, and memory of past behaviors determine how one will act in the future.[68]

James had a strong opinion about these schools of thought. He was, by nature, a pragmatist and thus took the view that one should use whatever parts of theories make the most sense and can be proven.[67] Therefore, he recommended breaking apart spiritualism and associationism and using the parts of them that make the most sense. James believed that each person has a soul, which exists in a spiritual universe, and leads a person to perform the behaviors they do in the physical world.[67] James was influenced by Emanuel Swedenborg, who first introduced him to this idea. James stated that, although it does appear that humans use associations to move from one event to the next, this cannot be done without this soul tying everything together. For, after an association has been made, it is the person who decides which part of it to focus on, and therefore determines in which direction following associations will lead.[66] Associationism is too simple in that it does not account for decision-making of future behaviors, and memory of what worked well and what did not. Spiritualism, however, does not demonstrate actual physical representations for how associations occur. James combined the views of spiritualism and associationism to create his own way of thinking.

James was a founding member and vice president of the American Society for Psychical Research.[69] The lending of his name made Leonora Piper a famous medium. In 1885, the year after the death of his young son, James had his first sitting with Piper at the suggestion of his mother-in-law.[70] He was soon convinced that Piper knew things she could only have discovered by supernatural means. He expressed his belief in Piper by saying, "If you wish to upset the law that all crows are black, it is enough if you prove that one crow is white. My white crow is Mrs. Piper."[71] However, James did not believe that Piper was in contact with spirits. After evaluating sixty-nine reports of Piper's mediumship he considered the hypothesis of telepathy as well as Piper obtaining information about her sitters by natural means such as her memory recalling information. According to James the "spirit-control" hypothesis of her mediumship was incoherent, irrelevant and in cases demonstrably false.[72]

James held séances with Piper and was impressed by some of the details he was given; however, according to Massimo Polidoro a maid in the household of James was friendly with a maid in Piper's house and this may have been a source of information that Piper used for private details about James.[73] Bibliographers Frederick Burkhardt and Fredson Bowers who compiled the works of James wrote "It is thus possible that Mrs. Piper's knowledge of the James family was acquired from the gossip of servants and that the whole mystery rests on the failure of the people upstairs to realize that servants [downstairs] also have ears."[74]

James was convinced that the "future will corroborate" the existence of telepathy.[75] Psychologists such as James McKeen Cattell and Edward B. Titchener took issue with James's support for psychical research and considered his statements unscientific.[76][77] Cattell in a letter to James wrote that the "Society for Psychical Research is doing much to injure psychology".[78]

James' theory of the selfJames' theory of the self divided a person's mental picture of self into two categories: the "Me" and the "I". The "Me" can be thought of as a separate object or individual a person refers to when describing their personal experiences; while the "I" is the self that knows who they are and what they have done in their life.[37] Both concepts are depicted in the statement; "I know it was me who ate the cookie." He called the "Me" part of self the "empirical me" and the "I" part "the pure Ego".[79] For James, the "I" part of self was the thinking self, which could not be further divided. He linked this part of the self to the soul of a person, or what is now thought of as the mind.[80] Educational theorists have been inspired in various ways by James's theory of self, and have developed various applications to curricular and pedagogical theory and practice.[59]

James further divided the "Me" part of self into: a material, a social, and a spiritual self, as below.[79]

Material selfThe material self consists of things that belong to a person or entities that a person belongs to. Thus, things like the body, family, clothes, money, and such make up the material self. For James, the core of the material self was the body.[80] Second to the body, James felt a person's clothes were important to the material self. He believed a person's clothes were one way they expressed who they felt they were; or clothes were a way to show status, thus contributing to forming and maintaining one's self-image.[80] Money and family are critical parts of the material self. James felt that if one lost a family member, a part of who they are was lost also. Money figured in one's material self in a similar way. If a person had significant money then lost it, who they were as a person changed as well.[80]

Social selfOur social selves are who we are in a given social situation. For James, people change how they act depending on the social situation that they are in. James believed that people had as many social selves as they did social situations they participated in.[80] For example, a person may act in a different way at work when compared to how that same person may act when they are out with a group of friends. James also believed that in a given social group, an individual's social self may be divided even further.[80] An example of this would be, in the social context of an individual's work environment, the difference in behavior when that individual is interacting with their boss versus their behavior when interacting with a co-worker.

Spiritual selfFor James, the spiritual self was who we are at our core. It is more concrete or permanent than the other two selves. The spiritual self is our subjective and most intimate self. Aspects of a spiritual self include things like personality, core values, and conscience that do not typically change throughout an individual's lifetime. The spiritual self involves introspection, or looking inward to deeper spiritual, moral, or intellectual questions without the influence of objective thoughts.[80] For James, achieving a high level of understanding of who we are at our core, or understanding our spiritual selves is more rewarding than satisfying the needs of the social and material selves.

Pure egoWhat James refers to as the "I" self. For James, the pure ego is what provides the thread of continuity between our past, present, and future selves. The pure ego's perception of consistent individual identity arises from a continual stream of consciousness.[81] James believed that the pure ego was similar to what we think of as the soul, or the mind. The pure ego was not a substance and therefore could not be examined by science.[37]

Notable works• The Principles of Psychology, 2 vols. (1890), Dover Publications 1950, vol. 1: ISBN 0-486-20381-6, vol. 2: ISBN 0-486-20382-4

• Psychology (Briefer Course) (1892), University of Notre Dame Press 1985: ISBN 0-268-01557-0, Dover Publications 2001: ISBN 0-486-41604-6

• Is Life Worth Living? (1895), the seminal lecture delivered at Harvard on April 15, 1895

• The Will to Believe, and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy (1897)

• Human Immortality: Two Supposed Objections to the Doctrine (the Ingersoll Lecture, 1897)

o The Will to Believe, Human Immortality (1956) Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-20291-7

• Talks to Teachers on Psychology: and to Students on Some of Life's Ideals (1899), Dover Publications 2001: ISBN 0-486-41964-9, IndyPublish.com 2005: ISBN 1-4219-5806-6

• The Varieties of Religious Experience: A Study in Human Nature (1902), ISBN 0-14-039034-0

• Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking (1907), Hackett Publishing 1981: ISBN 0-915145-05-7, Dover 1995: ISBN 0-486-28270-8

• A Pluralistic Universe (1909), Hibbert Lectures, University of Nebraska Press 1996: ISBN 0-8032-7591-9

• The Meaning of Truth: A Sequel to "Pragmatism" (1909), Prometheus Books, 1997: ISBN 1-57392-138-6

• Some Problems of Philosophy: A Beginning of an Introduction to Philosophy (1911), University of Nebraska Press 1996: ISBN 0-8032-7587-0

• Memories and Studies (1911), Reprint Services Corp: 1992: ISBN 0-7812-3481-6

• Essays in Radical Empiricism (1912), Dover Publications 2003, ISBN 0-486-43094-4

o critical edition, Frederick Burkhardt and Fredson Bowers, editors. Harvard University Press 1976: ISBN 0-674-26717-6 (includes commentary, notes, enumerated emendations, appendices with English translation of "La Notion de Conscience")

• Letters of William James, 2 vols. (1920)

• Collected Essays and Reviews (1920)

• Ralph Barton Perry, The Thought and Character of William James, 2 vols. (1935), Vanderbilt University Press 1996 reprint: ISBN 0-8265-1279-8 (contains some 500 letters by William James not found in the earlier edition of the Letters of William James)

• William James on Psychical Research (1960)

• The Correspondence of William James, 12 vols. (1992–2004) University of Virginia Press, ISBN 0-8139-2318-2

• "The Dilemma of Determinism"

• William James on Habit, Will, Truth, and the Meaning of Life, James Sloan Allen, ed. Frederic C. Beil, Publisher, ISBN 978-1-929490-45-5

Collections• William James: Writings 1878–1899 (1992). Library of America, 1212 p., ISBN 978-0-940450-72-1

Psychology: Briefer Course (rev. and condensed Principles of Psychology), The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy, Talks to Teachers and Students, Essays (nine others)

• William James: Writings 1902–1910 (1987). Library of America, 1379 p., ISBN 978-0-940450-38-7

The Varieties of Religious Experience, Pragmatism, A Pluralistic Universe, The Meaning of Truth, Some Problems of Philosophy, Essays

• The Writings of William James: A Comprehensive Edition (1978). University of Chicago Press, 912 pp., ISBN 0-226-39188-4

Pragmatism, Essays in Radical Empiricism, and A Pluralistic Universe complete; plus selections from other works

• In 1975, Harvard University Press began publication of a standard edition of The Works of William James.

See also• Biography portal

• Philosophy portal

• Psychology portal

• "The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life"

• Psychology of religion

• American philosophy

• List of American philosophers

• William James Lectures

• William James Society

References

Notes1. See his Defense of a Pragmatic Notion of Truth, written to counter criticisms of his Pragmatism's Conception of Truth (1907) lecture.

Citations 1. Goodman, Russell (2 June 2019). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2 June 2019 – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

2. Krey, Peter (2004), "The Ethics of Belief: William Clifford versus William", p. 1.

3. "Bill James, of Harvard, was among the first foreigners to take cognizance of Thought and Reality, already in 1873...", Lettres inédites de African Spir au professeur Penjon (Unpublished Letters of African Spir to professor Penjon), Neuchâtel, 1948, p. 231, n. 7.

4. Hoffman, Michael J. “Gertrude Stein in the Psychology Laboratory.” American Quarterly, vol. 17, no. 1, 1965, pp. 127–132. JSTOR,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/2711342. Accessed 2 Mar. 2020.

5. T.L. Brink (2008) Psychology: A Student Friendly Approach. "Unit One: The Definition and History of Psychology". p. 10

6. "William James: Writings 1878–1899". The Library of America. 1992-06-01. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

7. "William James: Writings 1902–1910". The Library of America. 1987-02-01. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

8. Dr. Megan E. Bradley. "William James". PSYography. Faculty.frostburg.edu. Archived from the original on 2014-11-24. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

9. Haggbloom, Steven J.; Warnick, Renee; Warnick, Jason E.; Jones, Vinessa K.; Yarbrough, Gary L.; Russell, Tenea M.; Borecky, Chris M.; McGahhey, Reagan; Powell III, John L.; Beavers, Jamie; Monte, Emmanuelle (2002). "The 100 most eminent psychologists of the 20th century". Review of General Psychology. 6 (2): 139–152. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139.

10. J. H. Korn, R. Davis, S. F. Davis: "Historians' and chairpersons' judgements of eminence among psychologists". American Psychologist, 1991, Volume 46, pp. 789–792.

11. "Wilhelm Maximilian Wundt" in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

12. Tom Butler-Bowdon: 50 Psychology Classics. Nicholas Brealey Publishing 2007. ISBN 1857884736. p. 2.

13. "William James". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University. Retrieved 2013-09-21.

14. James, William (2009). The Varieties of Religious Experience. The Library of America. pp. 74–120. ISBN 978-1598530629.

15. Sachs, Oliver (2008). Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain, Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Vintage Books. pp. xiii. ISBN 978-1-4000-3353-9.

16. Antony Lysy, "William James, Theosophist", The Quest Volume 88, number 6, November–December 2000.

17. Ralph Barton Perry, The Thought and Character of William James, vol. 1, (1935), 1996 edition: ISBN 0-8265-1279-8, p. 228.

18. "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original (Searchable database) on 2015-07-01. Retrieved 2016-02-01. Note: This includes Rachel D. Carley (January 2012). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Putnam Camp" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-02-01. and Accompanying photographs

19. Duane P. Schultz; Sydney Ellen Schultz (22 March 2007). A History of Modern Psychology. Cengage Learning. pp. 185–. ISBN 978-0-495-09799-0. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

20. Schmidt, Barbara. "A History of and Guide to Uniform Editions of Mark Twain's Works". twainquotes.com. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

21. Capps, Donald (October 23, 2015). The Religious Life: The Insights of William James. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781498219945 – via Google Books.

22. Haggbloom, S. J.; et al. (2002). "The 100 Most Eminent Psychologists of the 20th Century". Review of General Psychology. 6 (2): 139–152. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.6.2.139. Archived from the originalon 2006-04-29.. Haggbloom et al. combined 3 quantitative variables: citations in professional journals, citations in textbooks, and nominations in a survey given to members of the Association for Psychological Science, with 3 qualitative variables (converted to quantitative scores): National Academy of Science (NAS) membership, American Psychological Association (APA) President and/or recipient of the APA Distinguished Scientific Contributions Award, and surname used as an eponym. Then the list was rank ordered.

23. Kelly, Howard A.; Burrage, Walter L., eds. (1920). "James, William" . American Medical Biographies . Baltimore: The Norman, Remington Company.

24. John J. McDermott, The Writings of William James: A Comprehensive Edition, University of Chicago Press, 1977 revised edition, ISBN 0-226-39188-4, pp. 812–58.

25. William James' The Moral Equivalent of War Introduction by John Roland. Constitution.org. Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

26. William James' The Moral Equivalent of War – 1906. Constitution.org. Retrieved on 2011-08-28.

27. Harrison Ross Steeves; Frank Humphrey Ristine (1913). Representative essays in modern thought: a basis for composition. American Book Company. pp. 519–. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

28. ""The Moral Equivalent of War" by William James, McClure's Magazine, August 1910". UNZ.org. Retrieved 2016-11-25.

29. James, William. 1907. "Pragmatism's Conception of Truth" (lecture 6). Pp. 76–91 in Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking. New York: Longman Green and Co. Archived from the original 15 July 2006.

30. "Pragmatic Theory of Truth." Pp. 427–28 in Encyclopedia of Philosophy 6. London: Macmillan. 1969.

31. William James. 1907 [1906]. "What Pragmatism Means" (lecture 2). Pp. 17–32 in Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking. New York: Longman Green and Co. via The Mead Project, Brock University (2007). Available via Marxist Internet Archive (2005).

32. H. O. Mounce (1997). The two pragmatisms: from Peirce to Rorty. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-15283-9. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

33. James, William. 1909. The Meaning of Truth. New York: Longmans, Green, & Co. p. 177.

34. Gunn, Giles (2000). William James: Pragmatism and Other Writings. Penguin Group. pp. 24–40.

35. Burch, Robert (June 22, 2001). "Charles Sanders Peirce". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

36. Gunn, Giles (2000). William James: Pragmatism and Other Writings. Penguin Group. pp. 119–132.

37. Pomerleau, Wayne. "William James (1842–1910)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. IEP. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

38. James, William. 1897 [1882] “The Sentiment of Rationality.” The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. New York: Longmans, Green & Co.

39. James, William (2000) [1842-1910]. Pragmatism and other writings. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-043735-5. OCLC 943305535.

40. Legg, Catherine (14 March 2019). "Pragmatism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

41. Atkin, Albert. "Charles Sanders Peirce: Pragmatism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

42. Peirce, Charles S. 1878. "'How to Make Our Ideas Clear." Popular Science Monthly. — (excerpt). Pp. 212–218 in An Anthology of Nineteenth-Century American Science Writing, edited by C. R. Resetarits. Anthem Press. 2012. ISBN 978-0-85728-651-2. doi:10.7135/upo9780857286512.037

43. James, William (1 May 2002). "Pragmatism". The Project Gutenberg EBook of Pragmatism. Retrieved 12 November 2019.

44. Doyle, Bob. 2011. Free Will: the Scandal in Philosophy. I-Phi Press. The Information Philosopher.

45. James, William. 2009 [1887]. “The Will to Believe”, The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. New York: Longmans, Green & Co. at Project Gutenberg, produced by A. Haines.

46. James, William. 2018 [1918]. The Principles of Psychology, vol. 2, New York: Henry Holt and Company at Project Gutenberg, produced by C. Graham and M. D'Hooghe .

47. Viney, Donald Wayne (1986). "William James on Free Will and Determinism". The Journal of Mind and Behavior. 7 (4): 555–565. JSTOR 43853234.

48. Shouler, Kenneth A. 2008. The Everything Guide to Understanding Philosophy: the Basic Concepts of the Greatest Thinkers of All Time – Made Easy!. Adams Media.

49. Perry, Ralph Barton. The Thought and Character of William James 1. p. 323. — Letters of William James 1. p. 147.

50. James, William. 2009 [c. 1884]. “The Dilemma of Determinism”, The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. New York: Longmans, Green & Co. at Project Gutenberg, produced by A. Haines.

51. James, William. 1956 [1884]. “The Dilemma of Determinism.” In The Will to Believe and Other Essays in Popular Philosophy. New York: Dover.

52. Pomerleau, Wayne P. “William James (1842-1910).” Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "William James" Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Article.

53. Doyle, BOB (2010). "Jamesian Free Will, the Two-Stage Model of William James". William James Studies. 5: 1–28. JSTOR 26203733.

54. James, William (1985). The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Penguin Classics. p. 426.

55. William James, "Subjective Effects of Nitrous Oxide"

56. John Lachs and Robert Talisse (2007). American Philosophy: An Encyclopedia. p. 310. ISBN 978-0415939263.

57. "Mysticism Defined by William James".

http://www.bodysoulandspirit.net.[dead link]

58. Buss, David M. 2008. "Chapter 1." Pp. 2–35 in Evolutionary psychology: the new science of the mind. Pearson.

59. Ergas, Oren (2017). Reconstructing 'education' through mindful attention. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-58781-7.

60. Sergi, Giuseppe. 1858. L'origine dei fenomeni psichici e loro significazione biologica. Milano: Fratelli Dumolard. ISBN 1271529408.

61. Sergi, Giuseppe. 1894. "Storia Naturale dei Sentimenti." Principi di Psicologie: Dolore e Piacere. Milano: Fratelli Dumolard. ISBN 1147667462.

62. LeDoux, Joseph E. 1996. The Emotional Brain: the Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life. ISBN 0-684-83659-9. p. 43.

63. James, William. 1884. "What is an Emotion?" Mind 9:188–205.

64. Grinin L. E. 2010. "The Role of an Individual in History: A Reconsideration." Social Evolution & History 9(2):95–136. p. 103.

65. William James. 2007 [1880]. "Great Men, Great Thoughts and the Environment." Atlantic Monthly46:441–59.

66. James, William. 1985 [1892]. Psychology (Briefer Course). University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-01557-0.

67. Richardson, Robert D. 2006. William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-43325-2.

68. James, William. 1890. The Principles of Psychology.

69. Eugene Taylor. (2009). The Mystery of Personality: A History of Psychodynamic Theories. Springer. p. 30. ISBN 978-0387981031

70. Deborah Blum. (2007). Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life. Penguin Group. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-14-303895-5.

71. Gardner Murphy, Robert O. Ballou. (1960). William James on Psychical Research. Viking Press. p. 41

72. Francesca Bordogna. (2008). William James at the Boundaries: Philosophy, Science, and the Geography of Knowledge. University Of Chicago Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0226066523

73. Massimo Polidoro. (2001). Final Séance: The Strange Friendship Between Houdini and Conan Doyle. Prometheus Books. p. 36. ISBN 978-1573928960

74. Frederick Burkhardt and Fredson Bowers. (1986). Essays in Psychical Research. Harvard University Press. p. 397 in William James. The Works of William James. Edited by Frederick H. Burkhardt, Fredson Bowers, and Ignas K. Skrupskelis. 19 vols. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press. 1975–1988.

75. About the Shadow World. Everybody's Magazine. v. 20 (1909).

76. Lamont, Peter. (2013). Extraordinary Beliefs: A Historical Approach to a Psychological Problem. Cambridge University Press. pp. 184–188.

77. Kimble, Gregory A; Wertheimer, Michael; White, Charlotte. (2013). Portraits of Pioneers in Psychology. Psychology Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-8058-0620-2

78. Goodwin, C. James. (2015). A History of Modern Psychology. Wiley. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-118-83375-9

79. Cooper, W. E. (1992). "William James's theory of the self". Monist 75(4), 504.

80. "Classics in the History of Psychology (archived copy)". Archived from the original on 2013-12-06. Retrieved 2013-12-03.

81. "Introduction to William James".

http://www.uky.edu.

Sources• Essays Philosophical and Psychological in Honor of William James, by his Colleagues at Columbia University (London, 1908)

Further reading• James Sloan Allen,ed., William James on Habit, Will, Truth, and the Meaning of Life (2014). Frederic C. Beil, Publisher, ISBN 978-1-929490-45-5

• Margo Bistis, "Remnant of the Future: William James' Automated Utopia", in Norman M. Klein and Margo Bistis, The Imaginary 20th Century (Karlsruhe: ZKM, 2016).

• Émile Boutroux, William James (New York, 1912)

• Werner Bloch, Der Pragmatismus von James und Schiller nebst Exkursen über Weltanschauung und über die Hypothese (Leipzig, 1913)

• K. A. Busch, William James als Religionsphilosoph (Göttingen, 1911)

• Jacques Barzun. A Stroll with William James (1983). Harper and Row: ISBN 0-226-03869-6

• Deborah Blum. Ghost Hunters: William James and the Search for Scientific Proof of Life After Death (2006). Penguin Press, ISBN 1-59420-090-4

• Wesley Cooper. The Unity of William James's Thought (2002). Vanderbilt University Press, ISBN 0-8265-1387-5

• Howard M. Feinstein. Becoming William James (1984). Cornell University Press, ISBN 978-0-8014-8642-5

• Théodore Flournoy, La Philosophie de William James (Saint-Blaise, 1911)

• Sergio Franzese, The Ethics of Energy. William James's Moral Philosophy in Focus, Ontos Verlag, 2008

• Sergio Franzese & Felicitas Krämer (eds.), Fringes of Religious Experience. Cross-perspectives on William James's Varieties of Religious Experience, Frankfurt / Lancaster, ontos verlag, Process Thought XII, 2007

• Peter Hare, Michel Weber, James K. Swindler, Oana-Maria Pastae, Cerasel Cuteanu (eds.), International Perspectives on Pragmatism, Newcastle upon Tyne, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009

• James Huneker, "A Philosophy for Philistines" in his The Pathos of Distance (New York, 1913)

• Henry James's A Small Boy and Others (1913) and Notes of a Son and Brother (1914)

• Amy Kittelstrom, The Religion of Democracy: Seven Liberals and the American Moral Tradition. New York: Penguin, 2015.

• H. V. Knox, Philosophy of William James (London, 1914)

• R, W. B. Lewis The Jameses: A Family Narrative (1991) Farrar, Straus & Giroux

• Louis Menand. The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America (2001). Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, ISBN 0-374-52849-7.

• Ménard, Analyse et critique des principes de la psychologie de W. James (Paris, 1911) analyzes the lives and relationship between James, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Charles Sanders Peirce, and John Dewey.

• Gerald E. Myers. William James: His Life and Thought (1986). Yale University Press, 2001, paperback: ISBN 0-300-08917-1. Focuses on his psychology; includes 230 pages of notes.

• Giuseppe Sergi L'origine dei fenomeni psichici e loro significazione biologica, Milano, Fratelli Dumolard, 1885.

• Giuseppe Sergi Principi di Psicologie: Dolore e Piacere; Storia Naturale dei Sentimenti, Milano, Fratelli Dumolard, 1894.

• James Pawelski. The Dynamic Individualism of William James (2007). SUNY press, ISBN 0-7914-7239-6.

• R. B. Perry, Present Philosophical Tendencies (New York, 1912)

• Robert D. Richardson. William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism (2006). Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-618-43325-2

• Robert D. Richardson, ed. The Heart of William James (2010). Harvard U. Press, ISBN 978-0-674-05561-2

• Jane Roberts. The Afterdeath Journal of an American Philosopher: The View of William James (1978. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-018515-9.)

• Josiah Royce, William James and Other Essays on the Philosophy of Life (New York, 1911)

• J. Michael Tilley, "William James: Living Forward and the Development of Radical Empiricism," In Kierkegaard's Influence on Philosophy: Anglophone Philosophy, edited by Jon Stewart, 2012, Ashgate Publishing, 87–98.

• Linda Simon. Genuine Reality: A Life of William James (1998). Harcourt Brace & Company, ISBN 0-226-75859-1

• Michel Weber. Whitehead’s Pancreativism. Jamesian Applications. Ontos Verlag, 2011, ISBN 978-386838-103-0

• Michel Weber, "On Religiousness and Religion. Huxley’s Reading of Whitehead’s Religion in the Making in the Light of James’ Varieties of Religious Experience", Jerome Meckier and Bernfried Nugel (eds.), Aldous Huxley Annual. A Journal of Twentieth-Century Thought and Beyond, Volume 5, Münster, LIT Verlag, March 2005, pp. 117–32.

• Michel Weber, "James’s Mystical Body in the Light of the Transmarginal Field of Consciousness", in Sergio Franzese & Felicitas Krämer (eds.), Fringes of Religious Experience. Cross-perspectives on William James's Varieties of Religious Experience, Frankfurt / Lancaster, Ontos Verlag, Process Thought XII, 2007, pp. 7–37.

• Wiseman, R. (2012). Rip it up: The radically new approach to changing your life. London, UK: Macmillan

External links• Media from Wikimedia Commons

• Quotations from Wikiquote

• Texts from Wikisource

• Data from Wikidata

• William James Society

• Emory University: William James – major collection of essays and works online

• William James correspondence from the Historic Psychiatry Collection, Menninger Archives, Kansas Historical Society

• Harvard University: Life is in the Transitions: William James, 1842–1910 – online exhibition from Houghton Library

• Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: William James

• William James on Information Philosopher

• Booknotes interview with Linda Simon on Genuine Reality: A Life of William James, June 7, 1998

• William James: Looking for a Way Out

• New York Times obituary

• Works by William James at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about William James at Internet Archive

• Works by William James at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• William James at Find a Grave