by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/25/20

Mankind Quarterly

Discipline: Anthropology

Language: English

Edited by: Edward Dutton

Publication details

History: 1960–present

Publisher: Ulster Institute for Social Research

Frequency: Quarterly

Mankind Quarterly is a peer-reviewed academic journal that has been described as a "cornerstone of the scientific racism establishment", a "white supremacist journal",[1] an "infamous racist journal", and "scientific racism's keepers of the flame".[2][3][4] It covers physical and cultural anthropology, including human evolution, intelligence, ethnography, linguistics, mythology, and archaeology. It is published by the Ulster Institute for Social Research, which is presided over by Richard Lynn.[5]

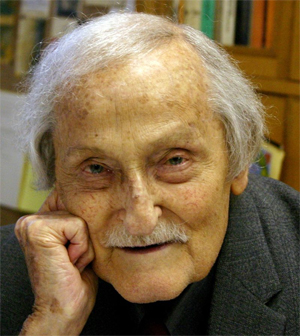

Richard Lynn (born 20 February 1930)[1] is a controversial English psychologist and author. He is a former professor emeritus of psychology at Ulster University, having had the title withdrawn by the university in 2018, and assistant editor of the journal Mankind Quarterly, which has been described as a "white supremacist journal". Lynn studies intelligence and is known for his belief in sex and racial differences in intelligence. Lynn was educated at King's College, Cambridge, in England. He has worked as lecturer in psychology at the University of Exeter and as professor of psychology at the Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin, and at the University of Ulster at Coleraine.

Many scientists have criticised Lynn's work on racial and national differences in intelligence for lacking scientific rigour, misrepresenting data, and for promoting a racialist political agenda. A number of scholars and intellectuals have said that Lynn is associated with a network of academics and organisations that promote scientific racism. In the late 1970s, Lynn wrote that he found that East Asians have a higher average intelligence quotient (IQ) than Europeans and Europeans have a higher average IQ than sub-Saharan Africans. In 1990, he proposed that the Flynn effect – the gradual increase in IQ scores observed around the world since the 1930s – could possibly be explained by improved nutrition. In two books co-written with Tatu Vanhanen, Lynn and Vanhanen argued that differences in developmental indexes among various nations are partially caused by the average IQ of their citizens. Earl Hunt and Werner Wittmann (2008) questioned the validity of their research methods and the highly inconsistent quality of the available data points that Lynn and Vanhanen used in their analysis. Lynn has also argued that the high fertility rate among individuals of low IQ constitutes a major threat to Western civilisation, as he believes people with low IQ scores will eventually outnumber high-IQ individuals. He has argued in favour of political measures to prevent this, including anti-immigration and eugenics policies, provoking heavy criticism internationally. Lynn's work was among the main sources cited in the book The Bell Curve, and he was one of 52 scientists who signed an opinion piece in the Wall Street Journal entitled "Mainstream Science on Intelligence", which endorsed a number of the views presented in the book.

Lynn sits on the editorial boards of the journals Personality and Individual Differences and Mankind Quarterly. Critics have called Mankind Quarterly a "cornerstone of the scientific racism establishment" and a "white supremacist journal". He is also on the board of the Pioneer Fund, which funds Mankind Quarterly and has also been described as racist in nature. Two of his recent books are on dysgenics and eugenics.

-- Richard Lynn, by Wikipedia

History

The journal was established in 1960 with funding from segregationists, who designed it to serve as a mouthpiece for their views. The costs of initially launching the journal were paid by the Pioneer Fund's Wickliffe Draper.[6]

Pioneer Fund is an American non-profit foundation established in 1937 "to advance the scientific study of heredity and human differences". The organization has been described as racist and white supremacist in nature, and as a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

From 2002 until his death in October 2012, the Pioneer Fund was headed by psychology professor J. Philippe Rushton. Rushton was succeeded by Richard Lynn.[5][6]

Two of the most notable studies funded by Pioneer Fund are the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart and the Texas Adoption Project, which studied the similarities and differences of identical twins and other children adopted into non-biological families.

Research backed by the fund on race and intelligence has generated controversy and criticism, such as the 1994 book The Bell Curve, which drew heavily from Pioneer-funded research. The fund also has ties to eugenics, and has both current and former links to white supremacist groups such as American Renaissance and Mankind Quarterly.

-- Pioneer Fund, by Wikipedia

Wickliffe Draper (August 9, 1891 – 1972) was an American political activist and philanthropist. He was an ardent eugenicist and lifelong advocate of strict racial segregation. In 1937, he founded the Pioneer Fund, a registered charitable organisation established to provide scholarships for descendants of original white American settlers and to support research into heredity and eugenics; he later became its principal benefactor.

-- Wickliffe Draper, by Wikipedia

The founders were Robert Gayre, Henry Garrett, Roger Pearson,...

Roger Pearson (born 21 August 1927 in London) is a British anthropologist, soldier, businessman, eugenics advocate, political organiser for the extreme right, and publisher of political and academic journals. He has been on the faculty of the Queens College, Charlotte, the University of Southern Mississippi, and Montana Tech, and is now retired. It has been noted that Pearson has been surprisingly successful in combining a career in academia with political activities on the far right. He served in the British Army after World War II, and was a businessman in South Asia. In the late 1950s he founded the Northern League.The Northern League was a neo-Nazi organisation founded by Roger Pearson. It was active in the United Kingdom and in northern continental Europe in the latter half of the 20th century.

Roger Pearson formed the Northern League in collaboration with Peter Huxley-Blythe, who was active in a variety of neo-Nazi groups with connections in Germany and North America. The League published the periodical The Northlander.

The stated purpose was to save the "Nordic race" from "annihilation of our kind" and to "fight for survival against forces which would mongrelize our race and civilization". The Northern League merged newsletters with Britons Publishing Company, an anti-Semitic publisher and a major distributor of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

Leading members of the Northern League included the Nazi racial eugenicist Hans F. K. Günther, who continued his work in the post-war period under a pseudonym. Other active members included the founder of Mankind Quarterly, Robert Gayre, and its editors Robert E. Kuttner and Donald A. Swan; the American segregationist Earnest Sevier Cox, the ex–Waffen SS officer and post-war neo-Nazi leader Arthur Ehrhardt, and a number of post-war British fascists, though even among fascists, the Northern League was considered extremist. Among its co-founders and activists were Alastair Harper, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) parliamentary candidate in Dunfermline West in 2001.

Northern League literature was written in the style of scientific racism (e.g., the work of Pearson's collaborator Raymond B. Cattell) and its Statement of Aims reflects 19th century conceptions of Rasse and Volk. Andrew S. Winston of the University of Guelph writes in an analysis of this group:

"According to the 'Aims', Northern Europeans are the 'purest survival of the great Indo-European family of nations, sometimes described as the Caucasian race and at other times as the Aryan race'. Almost all the 'classic civilisations of the past were the product of these Indo-European peoples'. Intermarriage with conquered peoples was said to produce the decay of these civilizations, particularly through interbreeding with slaves. 'The rising tide of Color"' threatens to overwhelm European society, and would result in the 'biological annihilation of the subspecies', according to the Northern League."

-- Northern League (United Kingdom), by Wikipedia

In the 1960s he established himself in the United States for a while working together with Willis Carto publishing white supremacist and anti-Semitic literature.

Pearson's anthropological work is based in the eugenic belief that "favorable" genes can be identified and segregated from "unfavorable" ones. He advocates a belief in biological racialism, and claims that human races can be ranked. Pearson argues that the future of the human species depends on political and scientific steps to replace the "genetic formulae" and populations that he considers to be inferior with ones he considers to be superior.

Pearson also published two popular textbooks in anthropology, but his anthropological views on race have been widely rejected as unsupported by contemporary anthropology. In 1976 he found the Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies, which has been identified as one of two international journals which regularly publishes articles pertaining to race and intelligence with the goal of supporting the idea that white people are inherently superior (the other such journal being Mankind Quarterly). In 1978 he took over the editorship of Mankind Quarterly founded by Robert Gayre and Henry Garrett, widely considered a scientific racist journal. Most of Pearson's publishing ventures have been managed through the Institute for the Study of Man, and the Pioneer Fund, with which Pearson is closely associated, having received $568,000 in the period from 1981-1991.

Pearson's opposition to egalitarianism extends to Marxism and socialism. In the 1980s, he was a political organizer for the American far-right; he established the Council for American Affairs and was the American representative in the World Anti-Communist League. As World Chairman of the WACL he worked with the U.S. government during the cold war, and he collaborated with many anti-communist groups in the organisation, including the Unification Church and former German Nazis.

On his website, Pearson disputes specific accusations of race-hate, of anti-semitism, of arguing in favor of genocide, involuntary eugenics, forced repatriation of legal immigrants, subjugation or exploitation by one group of another, extreme or fascist politics—including National Socialism or any totalitarian system—as well as denying accusations of impropriety.

-- Roger Pearson (anthropologist), by Wikipedia

Corrado Gini, Luigi Gedda (Honorary Advisory Board),[7] Otmar von Verschuer and Reginald Ruggles Gates. Another early editor was Herbert Charles Sanborn,[8] formerly the chair of the department of Philosophy and Psychology at Vanderbilt University from 1921 to 1942. It was originally published in Edinburgh, Scotland, by the International Association for the Advancement of Ethnology and Eugenics, an organization founded by Draper to promote eugenics and scientific racism.[6][/b]

Its foundation may in part have been a response to the declaration by UNESCO, which dismissed the validity of race as a biological concept, and to attempts to end racial segregation in the American South.[9][10]

In 1961, physical anthropologist Juan Comas published a series of scathing critiques of the journal arguing that the journal was reproducing discredited racial ideologies, such as Nordicism and anti-Semitism, under the guise of science.[11][12] In 1963, after the journal's first issue, contributors U. R. Ehrenfels, T. N. Madan, and Juan Comas said that the journal's editorial practice was biased and misleading.[13] In response, the journal published a series of rebuttals and attacks on Comas.[14] Comas argued in Current Anthropology that the journal's publication of A. James Gregor's review of Comas' book Racial Myths was politically motivated. Comas claimed the journal misrepresented the field of physical anthropology by adhering to outdated racial ideologies, for example by claiming that Jews were considered a "biological race" by the racial biologists of the time. Other anthropologists complained that paragraphs that did not agree with the racial ideology of the editorial board were deleted from published articles without the authors' agreement.[13][15][16][17]

Few academic anthropologists would publish in the journal or serve on its board; when Gates died, Carleton S. Coon, an anthropologist sympathetic to the hereditarian and racialistic view of the journal, was asked to replace him, but he rejected the offer stating that "I fear that for a professional anthropologist to accept membership on your board would be the kiss of death". The journal continued to be published supported by grant money.[16] Publisher Roger Pearson received over a million dollars in grants from the Pioneer Fund in the 1980s and 1990s.[18][19][20]

During the "Bell Curve wars" of the 1990s, the journal received attention when opponents of The Bell Curve publicised the fact that some of the works cited by Bell Curve authors Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray had first been published in Mankind Quarterly.[18] In The New York Review of Books, Charles Lane referred to The Bell Curve's "tainted sources", that seventeen researchers cited in the book's bibliography had contributed articles to, and ten of these seventeen had also been editors of, Mankind Quarterly, "a notorious journal of 'racial history' founded, and funded, by men who believe in the genetic superiority of the white race."[21]

The journal has been published by the Ulster Institute for Social Research since January 2015, when publication duties were transferred from Pearson's Council for Social and Economic Studies (which had published the journal since 1979).[22]

Editors

The editor-in-chief is Richard Lynn.[22] Previous editors include Roger Pearson, Gerhard Meisenberg and Edward Dutton.

Hereditarianism and politics

Many of those involved with the journal are connected to academic hereditarianism. The journal has been criticised as being political and strongly right-leaning,[23] supporting eugenics,[24] racist or fascist.[25][26]

Abstracting and indexing

• ATLA Religion Database[27]

• International Bibliography of the Social Sciences[28]

• Linguistics & Language Behavior Abstracts[28]

• Modern Language Association Database[28]

• Scopus[29]

See also

• Intelligence (journal)

• Journal of Social, Political, and Economic Studies

• Neue Anthropologie

• The Occidental Quarterly

• OpenPsych

• Journal of Historical Review

References

1. Gresson, Aaron; Kincheloe, Joe L.; Steinberg, Shirley R. (eds.). Measured Lies: The Bell Curve Examined (1st St. Martin's Griffin ed.). St. Martin's Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-312-17228-2.

2. Ibrahim G. Aoudé, The ethnic studies story: politics and social movements in Hawaiʻi, University of Hawaii Press, 1999, pg. 111

3. Kenneth Leech, Race, Church Publishing, Inc., 2005, pg. 14

4. William H. Tucker, The funding of scientific racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund, University of Illinois Press, 2002, pg. 2

5. "Home Page". Ulster Institute for Social Research. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

6. Schaffer, G. (2 September 2008). Racial Science and British Society, 1930-62. Springer. pp. 142–3. ISBN 9780230582446.

7. Cassata F (2008). "Against UNESCO: Gedda, Gini and American scientific racism". Med Secoli. 20(3): 907–35. PMID 19848223.

8. "History and Philosophy". Mankind Quarterly. Retrieved 22 September 2015 – via Internet Archive.

9. Schaffer, Gavin (2007). ""'Scientific' Racism Again?": Reginald Gates, the "Mankind Quarterly" and the Question of "Race" in Science after the Second World War". Journal of American Studies. 41 (2): 253–278. JSTOR 27557994. The Mankind Quarterly was designed as an objective foil to the folly of UNESCO and "post-racial" science.

10. Jackson, John P. (2005). Science for Segregation: Race, Law, and the Case against Brown v. Board of Education. NYU Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-8147-4271-6. Lay summary (30 August 2010). While the IAAEE scientists were deep into the fight to preserve racial segregation in the American South, they were also involved in a battle on a different front. They had launched their own journal, Mankind Quarterly, which purported to be dedicated to an open discussion of the scientific study of racial issues.

11. Comas Juan (1961). ""Scientific" Racism Again?". Current Anthropology. 2 (4): 303–340. doi:10.1086/200208.

12. Comas Juan (1962). "More on "Scientific" Racism". Current Anthropology. 3 (3): 284–302. doi:10.1086/200293.

13. Ehrenfels, U. R.; Madan, T. N.; Comas, J. (1962). "Mankind Quarterly Under Heavy Criticism: 3 Comments on Editorial Practices". Current Anthropology. 3 (2): 154–158. doi:10.1086/200265. JSTOR 2739528.

14. Gates, R. R. & Gregor, A. J. (1963). "Mankind Quarterly: Gates and Gregor Reply to Critics". Current Anthropology. 4 (1): 119–121. doi:10.1086/200345. JSTOR 2739826.

15. John P. Jackson. 2005. Science for Segregation: Race, Law, and the Case Against Brown V. Board of Education. NYU Press 151–154

16. Paul A. Erickson, Liam Donat Murphy. 2013. Readings for A History of Anthropological Theory. University of Toronto Press, p. 534

17. Harrison G. Ainsworth (1961). "The Mankind Quarterly". Man. 61: 163–164. doi:10.2307/2796948. JSTOR 2796948.

18. Tucker, William H. (2007). The funding of scientific racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07463-9. Lay summary (4 September 2010).

19. Mehler, Barry (7 July 1998). Race Science and the Pioneer Fund Originally published as "The Funding of the Science" in Searchlight, No. 277.

20. Genoves, Santiago (8 December 1961). "Racism and "The Mankind Quarterly"". Science. 134 (3493): 1928–1932. doi:10.1126/science.134.3493.1928. ISSN 1095-9203. PMID 17831127.

21. Weyher, Harry F.; Lane, Charles (2 February 1995). "'The Bell Curve' and Its Sources". The New York Review of Books.

22. Editorial Panel, Mankind Quarterly, retrieved 1 March 2020

23. e.g., Arvidsson, Stefan (2006), Aryan Idols: Indo-European Mythology as Ideology and Science, translated by Sonia Wichmann, Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press.

24. Mehler, Barry (December 1989). "Foundation for fascism: The new eugenics movement in the United States". Patterns of Prejudice. 23 (4): 17–25. doi:10.1080/0031322X.1989.9970026.

25. Schaffer, Gavin (2008). Racial science and British society, 1930–62. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

26. Gelb, Steven A. (1997). "Heart of Darkness: The Discreet Charm of the Hereditarian Psychologist". The Review of Education/Pedagogy/Cultural Studies. 19 (1): 129–139. doi:10.1080/1071441970190110.

27. "Title and Product Update Lists". ATLA Religion Database. American Theological Library Association. Retr"Mankind Quarterly". MIAR: Information Matrix for the Analysis of Journals. University of Barcelona. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

29. "Source details: Mankind Quarterly". Scopus preview. Elsevier. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

Further reading

• Anderson, Scott; Anderson, Jon Lee (1986). Inside the League. Dodd, Mead. ISBN 978-0-396-08517-1.

• Tucker, William H. (1996). The Science and Politics of Racial Research. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-06560-6. Lay summary (7 November 2010).

• Tucker, William H. (2009). The Cattell Controversy: Race, Science, and Ideology. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03400-8. Lay summary (30 August 2010).

External links

• Official website