by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/27/20

Emily?

In the 1970's, a major psi research effort began at the California think-tank, SRI International, in Menlo Park, California, USA (formerly called Stanford Research Institute). The program was established run by (The Cognitive Sciences Laboratory of a similar organization). (The Palo Alto based in the Cognitive Sciences Laboratory of Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC). link> Harold Puthoff, later Russell Targ joined the program, and then Edwin May. The SRI program concentrated on remote viewing research (and coined the term). May took over the program in 1985 when Puthoff left for another position. When May left SRI International in 1989, he reestablished a similar psi research program within the international science-for-hire organization called SAIC (Science Applications International Corporation), located in Palo Alto, California, USA. That program is still engaged in research and is best known for using sophisticated technologies, like magnetoencephalographs (MEG), to study brain functioning while individuals perform psi tasks, and theoretical models of micros-PK. The laboratory also develops theoretical models of __-PIC and approaches remote viewing research more than the "physicalist" perspective.

At about the same time that the SRI program began, another psi research program was established by Montague Ullman and Stanley Krippner at the Maimonides Hospital in Brooklyn, New York, USA. (No -- much earlier) This team, which later included Charles Honorton, is best known for their work in dream telepathy. Just as this program was winding down in 1979, Charles Honorton opened a new lab, called the Psychophysical Research Laboratories, in Princeton, New Jersey, USA. Honorton's lab, which continued operating until 1989, was best known for research on telepathy in the ganzfeld, micro-PK tests, and meta-analytic work.

Also in 1979, another psi research program began in Princeton, New Jersey, within the School of Engineering at Princeton University. This was founded by Robert Jahn, then the Dean of the School of Engineering. The Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research (PEAR) lab is still conducting research, and is best known for its massive databases on micro-PK tests, PK tests involving other physical systems, its "precognitive remote perception" experiments, and its theoretical work attempting to link metaphors of quantum mechanics to psi functioning.

Marilyn: please write a paragraph on the Mind Science Foundation, along with dates of operation. Could you write a similar paragraph about SURF too please?

Dick: please write about the University of Utrecht and now University of Amsterdam

Deborah: please write about Edinburgh University, unless I should steal this text from the Koestler Chair EU Web site?

I'll add something about my (Dean's) program at UNLV on the last wrap.

-- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) about Parapsychology, DRAFT 3, by cia.gov, 1991/1992?, Working notes -- Ed May 6/6/95, In "C2 May -- SAIC" folder, Box D, Approved For Release 2003/09/16: CIA-RDP96-00791R000200190055-7

Leidos Holdings, Inc.

Type

Public

Traded as

NYSE: LDOS

S&P 500 component

ISIN US5253271028 Edit this on Wikidata

Industry National security, defense, healthcare, engineering

Predecessor

Science Applications Incorporated (SAI)

Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC)

Founded June 1969; 51 years ago

La Jolla, San Diego, California, U.S.

McLean, Virginia, U.S.

Founder J. Robert "Bob" Beyster

Headquarters Reston, Virginia, U.S.

Key people

Roger Krone (CEO)

Revenue Increase US$10.17 billion[1] (2017)

Operating income

Increase US$559 million[1] (2017)

Net income

Increase US$364 million[1] (2017)

Number of employees

32,000[1] (2017)

Website leidos.com

Footnotes / references

[1][2][3][4][5]

Leidos, formerly known as Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC),[6] is an American defense, aviation, information technology, and biomedical research company headquartered in Reston, Virginia, that provides scientific, engineering, systems integration, and technical services. Leidos works extensively with the United States Department of Defense (4th largest DoD contractor FY2012), the United States Department of Homeland Security, and the United States Intelligence Community, including the NSA, as well as other U.S. government civil agencies and selected commercial markets.

History

As SAIC

SAIC company logo (2010)

The company was founded by J. Robert "Bob" Beyster in 1969 in the La Jolla neighborhood of San Diego, California, as Science Applications Incorporated (SAI).[7][8] Beyster, a former scientist for the Westinghouse Atomic Power Division,[9] and Los Alamos National Laboratory[10] who became the chairman of the Accelerator Physics Department of General Atomics in 1957,[11] raised the money to start SAI by selling stock he had received from General Atomics, combined with funds raised from the early employees who bought stock in the young enterprise.[12]

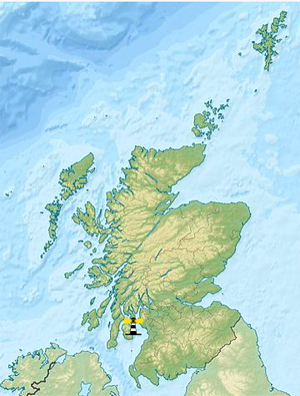

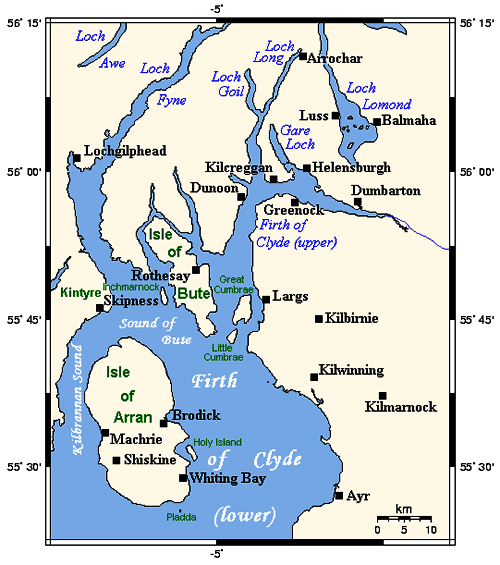

Initially the company's focus was on projects for the U.S. government related to nuclear power and weapons effects study programs. The company was renamed Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) as it expanded its operations. Major projects during Beyster's tenure included work on radiation therapy for the Los Alamos National Laboratory; technical support and management assistance to the development of the cruise missile in the 1970s; the cleanups of the Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station after its major accident, and of the contaminated community of Love Canal; design and performance evaluation of the Stars & Stripes 87, the winning ship for the 1987 America's Cup; and the design of the first luggage inspection machine to pass new Federal Aviation Administration tests following the terrorist bombing of Pan American flight 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland.[13]

Contrary to traditional business models, Beyster originally designed SAIC as an employee-owned company.[7][8] This shared ownership was accompanied by shared responsibility and freedom in business development, and allowed SAIC to attract and retain highly educated and motivated employees that helped the company to grow and diversify. After Beyster's retirement in 2003, SAIC conducted an initial public offering of common stock on October 17, 2006.[14] The offering of 86,250,000 shares of common stock was priced at $15.00 per share. The underwriters, Bear Stearns and Morgan Stanley, exercised overallotment options, resulting in 11.25 million shares. The IPO raised US$1.245B.[14] Even then, employee shares retained a privileged status, having ten times the voting power per share over common stock.[15]

In September 2009 SAIC relocated its corporate headquarters to their existing facilities in Tysons Corner in unincorporated Fairfax County, Virginia, near McLean.[16]

In 2012 SAIC was ordered to pay $550 million to the City of New York for overbilling the city over a period of seven years on the CityTime contract.[17] In 2014 Gerard Denault, SAIC's CityTime program manager, and his government contact were sentenced to 20 years in prison for fraud and bribery related to that contract.[18]

As Leidos

Leidos employees in 2017 Capital Pride in Washington, D.C.

In August 2012, SAIC announced its plans to split into two publicly traded companies.[19][20] The company spun off about a third of its business, forming an approximately $4 billion-per-year service company focused on government services, including systems engineering, technical assistance, financial analysis, and program office support. The remaining part became a $7 billion-per-year IT company specializing in technology for the national security, health, and engineering sectors. The smaller company was led by Tony Moraco, who beforehand was leading SAIC's Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance group, and the bigger one was led by John P. Jumper.[21] The split has allowed both companies to pursue more business, which it could not pursue as a single company which would have resulted in conflicts of interest.[22] In February 2013, it was announced that the smaller spin-off company would get the name "Science Applications International Corporation" and stay in the current headquarters, while the larger company would change its name to Leidos,[23] (created by clipping the word kaleidoscope) and would move its headquarters to Reston.[24] The split was structured in a way that SAIC changed its name to Leidos, then spun off the new SAIC as a separate publicly traded company. However, Leidos is the legal successor of the original SAIC and retains SAIC's pre-2013 stock price and corporate filing history.[25]

On September 27, 2013, SAIC changed its name to Leidos and spun off a new and independent $4 billion government services and information technology company which retained the Science Applications International Corporation name; Leidos is the direct successor to the original SAIC.[2][3] Before the split, Leidos employed 39,600 employees and reported $11.17 billion in revenue and $525 million net income for its fiscal year ended January 31, 2013,[6] making it number 240[26] on the Fortune 500 list. In 2014, Leidos reported US$5.06 billion in revenue.[3]

In August 2016, the deal to merge with the entirety of Lockheed Martin's Information Systems & Global Solutions (IS&GS) business came to a close, more than doubling the size of Leidos and its portfolio, and positioning the company as the global defense industry's largest enterprise in the federal technology sector.[27] As of February 2019, the company has 32,000 employees.[1] In 2018, Leidos reported US$10.19 billion in revenue. It ranked 311 on the 2019 Fortune 500 list.[28]

In January 2020, Leidos purchased defense contractor Dynetics for approximately $1.65 billion.[29][30][31]

Structure

Leidos has four central divisions: Civil, Health, Advanced Solutions, and Defense & Intelligence. The Civil Division focuses on integrating aviation systems, securing transportation measures, modernizing IT infrastructure, and engineering energy efficiently. The Health Division focuses on optimizing medical enterprises, securing private medical data, and improving collection and data entry methods. The Advanced Solutions Division is centered around data analysis, integrating advanced defense and intelligence systems, and increasing surveillance and reconnaissance efficiency. The Defense & Intelligence Division focuses on providing air service systems, geospatial analysis, cybersecurity, intelligence analysis, and supporting operations efforts.[32]

Management

CEO: Roger Krone[33][34]

After more than 30 years of Beyster's leadership, Kenneth C. Dahlberg was named the CEO of SAIC in November 2003.[35] In May 2005, the company changed its external tagline from An Employee-Owned Company to From Science to Solutions.

The third CEO was Walt Havenstein, who pushed for tighter integration of the company's historically autonomous divisions, which led to lower profit and revenue. The strategy was reversed by the fourth CEO, retired Air Force general John P. Jumper, appointed in 2012.[36] On July 1, 2014, Leidos announced that Roger Krone would become its CEO on July 14, 2014.[33] As of 2019, Krone is the Chairman and CEO of Leidos.[34]

Headquarters

In January 2018, Leidos announced it would move within Reston, VA, a quarter mile from 11951 Freedom Drive to 1750 Presidents Street. The new building was completed in early 2020.[37][38][39]

Operations

The Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) transitioned a Remote Viewing Program to SAIC in 1991 which was renamed Stargate Project.

Who is Edwin May?

Edwin C. May, Ph.D. is internationally known for his work in parapsychology. Having spent the first part of his research career in his chosen Ph.D.-degreed discipline, Low Energy, Experimental Nuclear Physics, he became interested in serious parapsychology in 1971. At that time, he was peripherally involved in a psychokinesis (i.e. putative mind over matter) experiment that was being conducted informally in the physics department at the University of California at Davis. Starting in August 1974, Dr. May spent nearly a year in India researching so-called psychic phenomena with Yogis and other Masters. In 1975, he returned to the States and worked for eight months with Charles Honorton at Maimonides Medical Center in Brooklyn, NY. It was there where he was introduced to formal research parapsychology. Beginning in 1976, Dr. May joined the on-going, U.S. Government-sponsored work at SRI International (formerly called Stanford Research Institute). In 1985, he inherited the program directorship of what was now called the Cognitive Sciences Program. Dr. May shifted that program to Science Applications International Corporation in 1991. Dr. May’s association with government-sponsored parapsychology research ended in 1995, when the program, now called STAR GATE, was closed.

Dr. May has managed complex, interdisciplinary research projects for the US federal government since 1985. He presided over 70% of the funding ($20M+) and 85% of the data collection for the government’s 22-year involvement in parapsychological research. His responsibilities included fund raising, personnel management, project administration and planning, and he was the guiding force for the technical research effort. Currently, Dr. May is the Executive Director of the Cognitive Sciences Laboratory, which now resides within the Laboratories for Fundamental Research.

He accumulated over 12 years experience in experimental nuclear physics research, which included the study of nuclear reaction mechanism and nuclear structure. Dr. May’s accelerator experience includes a variety of tandem Van de Graaff generators and cyclotrons operating under 50 million electron volts. Other specialize experience includes four years of ?-ray spectroscopy, one year of trace-element analysis (x-ray, and a-particle techniques), numerical analysis, Monte Carlo techniques, digital signal processing, and cardiac blood flow research. In addition, he has conducted physiology research through the careful investigation of the efficacy of biofeedback in a clinical setting.

Dr. May is fluent in a variety of 3-GL and 4-GL computer languages including C, FORTRAN, IDL, Visual Basic, various machine codes, and SQL.

Dr. May’s eclectic background has provided him with significant expertise in a variety of seemingly unrelated disciplines; thus, he is ideally suited and experienced to direct interdisciplinary research. His Dissertation was “Nuclear Reaction Studies via the (p,pn) Reaction on Light Nuclei and the (d,pn) Reaction on Medium to Heavy Nuclei.” B. L. Cohen, advisor. University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA (1968). He is the author or co-author of a total of 130 reports: 16 papers in experimental nuclear physics: 30 papers presented at technical conferences on anomalous cognition; 19 abstracts presented at professional conferences on physics; 79 technical or administrative reports to various clients; and 14 miscellaneous reports and proposals. The Parapsychological Association, an affiliate member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, granted him the Outstanding Achievement Award for his contribution for research excellence. He was President, The Parapsychological Association for 1997.

For more detailed information on Stargate, go to Cognitive Sciences Laboratory website.

Further Reading:

The American Institutes for Research Review of the Department of Defense's STAR GATE Program: A Commentary by Edwin May

May, E. C., Utts, J. M., Humphrey, B. S., Luke, W. L. W., Frivold, T. J., and Trask, V. V. (1990). Advances in Remote-Viewing Analysis. Journal of Parapsychology, 54, 193-228.

May, E. C. and Vilenskaya, L. (1992). Overview of Current Parapsychology Research in the Former Soviet Union. Subtle Energies, 3, No. 3, 45-67.

May, E. C., Spottiswoode, S. J. P., and James, C. L. (1994). Managing the Target-Pool Bandwidth: Possible Noise Reduction for Anomalous Cognition Experiments. Journal of Parapsychology, 58, 303-313.

May, E. C., Spottiswoode, S. J. P. and James, C. L. (1994). Shannon Entropy: A Possible Intrinsic Target Property. Journal of Parapsychology, 58, 384-401.

-- History of the PA Presidency, by parapsych.org

In March 2001 SAIC defined the concept for the NSA Trailblazer Project. In 2002, NSA contracted SAIC for $280 million to produce a "technology demonstration platform" for the agency's project, a "Digital Network Intelligence" system to analyze data carried on computer networks. Other project participants included Boeing, Computer Sciences Corporation, and Booz Allen Hamilton.[40] According to science news site PhysOrg.com, Trailblazer was a continuation of the earlier ThinThread program.[41] In 2005, NSA director Michael Hayden told a Senate hearing that the Trailblazer program was several hundred million dollars over budget and years behind schedule.[42]

In fiscal year 2003, SAIC did more than $2.6 billion in business with the United States Department of Defense, making it the ninth-largest defense contractor in the United States. Other large contracts included a bid for information technology for the 2004 Olympics in Greece.[43]

From 2001 to 2005, SAIC was the primary contractor for the FBI's unsuccessful Virtual Case File project.[44]

During fiscal year 2012 (latest figure available), SAIC had more than doubled its business with the DoD to $5,988,489,000, and was the 4th-largest defense contractor on the annual list of the top 100.[45] Leidos ranked 292 on the 2017 Fortune 500 list.[28]

Subsidiaries

• Dynetics, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of Leidos since Jan 2020.[46]

• Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., formerly SAIC - Frederick, a wholly owned subsidiary of Leidos manages Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research.[47]

• MEDPROTECT, LLC supports US government health-payer organizations[47]

• Reveal, develops dual-energy X-ray computed tomography systems for explosives-detection at airports and similar facilities[48]

• CloudShield Technologies a wholly owned subsidiary, specializing in cyber-security

• Varec, Inc., liquid petroleum asset management company

• Leidos Health

• Leidos Canada, formerly SAIC Canada, wholly owned subsidiary, works with Canadian government.[47]

• Leidos Australia (Leidos Pty Ltd), wholly owned subsidiary, specializing in document technologies and cyber-security.[47] Produces TeraText software.

• Leidos UK (Leidos Innovations UK Ltd, Leidos Europe Ltd, Leidos Supply Ltd & Leidos Ltd), wholly owned subsidiary, specializing in managed IT Services, developing of bespoke products. Produces, supports & maintains the Chroma Airport Suite, also responsible for the MOD's Supply Chain.

• Leidos Engineering, LLC, formerly SAIC Energy, Environment & Infrastructure LLC, assembles the legacy of engineering capabilities of Benham Investment Holdings, LLC, R. W. Beck Group, Inc.,[49] and Patrick Energy Services.

• QTC Management, Inc., acquired by merging with Lockheed Martin IS&GS.

• Systems Made Simple (SMS), acquired by merging with Lockheed Martin IS&GS.

Former subsidiaries

AMSEC LLC, a business partnership between SAIC and Northrop Grumman subsidiary Newport News Shipbuilding divested on July 13, 2007. Network Solutions was acquired by SAIC in 1995,[50] and subsequently was acquired by VeriSign, Inc. for $21 billion.[51]Leidos Cyber, Inc., formerly Lockheed Martin Industrial Defender, acquired by merging with Lockheed Martin IS&GS, was sold to Capgemini in 2018.[52]

Controversies

As SAIC

Then-SAIC had as part of its management and on its board of directors, many well-known ex-government personnel including Melvin Laird, Secretary of Defense in the Nixon administration; William Perry, Secretary of Defense for Bill Clinton; John M. Deutch, President Clinton's CIA Director; Admiral Bobby Ray Inman who served in various capacities in the NSA and CIA for the Ford, Carter and Reagan administrations; and David Kay who led the search for weapons of mass destruction after the 1991 Gulf War and served under the Bush Administration after the 2003 Iraq invasion. In 2012, 26 out of 35 SAIC Inc. lobbyists previously held government jobs.[53][54]

In June 2001 the FBI paid SAIC $122 million to create a Virtual Case File (VCF) software system to speed up the sharing of information among agents. But the FBI abandoned VCF when it failed to function adequately. Robert Mueller, FBI Director, testified to a congressional committee, "When SAIC delivered the first product in December 2003 we immediately identified a number of deficiencies – 17 at the outset. That soon cascaded to 50 or more and ultimately to 400 problems with that software ... We were indeed disappointed."[55]

In 2005, then-SAIC executive vice president Arnold L. Punaro claimed that the company had "fully conformed to the contract we have and gave the taxpayers real value for their money." He blamed the FBI for the initial problems, saying the agency had a parade of program managers and demanded too many design changes. He stated that during 15 months that SAIC worked on the program, 19 different government managers were involved and 36 contract modifications were ordered.[56] "There were an average of 1.3 changes every day from the FBI, for a total of 399 changes during the period," Punaro said.[57]

In 2011–2012, then-SAIC was among the 8 top contributors to federal candidates, parties, and outside groups with $1,209,611 during the 2011–2012 election cycle according to information from the Federal Election Commission. The top candidate recipient was Barack Obama.[58]

As Leidos

In a heavily redacted report dated January 3, 2018, the Inspector General for the Department of Defense determined that a supervisor at Leidos made “inappropriate sexual and racial comments to” a female contractor, and that when she complained of a hostile work environment, Leidos retaliated by excluding her from further work on an additional contract.[59] The report found that Leidos's claim that the contract employee “exhibited poor performance throughout her employment" lacked supporting evidence. It recommended that U.S. Secretary of Defense Jim Mattis “consider appropriate action against Leidos” such as “compensatory damages, including back pay, employee benefits and other terms and conditions of employment” that the contractor would have received under the additional contract.

See also

· CIA

· Top 100 US Federal Contractors

References

1. "Leidos Holdings, Inc. Reports Fourth Quarter and Fiscal Year 2017 Results" (PDF). February 28, 2018.

2. Aitoro, Jill R. (September 27, 2013). "What to expect from Leidos and SAIC when they start trading Sept. 30". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

3. Aitoro, Jill R. (September 27, 2013). "Exclusive: John Jumper explains why the Leidos-SAIC split had to happen". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved September 26, 2013.

4. "www.leidos.com". Retrieved September 29, 2013.

5. "SAIC, Inc.'s Board of Directors Approves Spin-Off of its Services Business". September 9, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

6. Science Applications International Corporation. "Fiscal Year 2013 annual report on Form 10-K"(PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 2, 2013. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

7. Dr. J. Robert Beyster with Peter Economy, The SAIC Solution: How We Built an $8 Billion Employee-Owned Technology Company, John Wiley & Sons (2007) p.xiii

8. Glass, Jon W. (April 3, 2007). "SAIC creator's book touts employee ownership". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved November 27, 2014. Beyster, 82, retired as SAIC's chairman in July 2004. A nuclear physicist by training and a self-described "evangelist" for employee-owned companies, Beyster said he wrote the book to provide entrepreneurs and business executives a model. He wrote it with Peter Economy, an author or co-author of several business books.

9. "SAIC, Leidos founder dead at 90". Federal News Network. December 23, 2014.

10. report, Daily Transcript staff (December 23, 2014). "SAIC founder J. Robert Beyster dies at age 90". The Daily Transcript.

11. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 23, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

12. "SAIC founder J. Robert Beyster dies". San Diego Union-Tribune. December 23, 2014.

13. "Our History". Leidos. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

14. SAIC - News & Media - "SAIC, Inc. Announces Closing of Initial Public Offering" ArchivedOctober 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Investors.saic.com. Retrieved on August 17, 2013.

15. Bigelow, Bruce V (September 2, 2005). "Long owned by employees, SAIC says it's going public". San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved June 16, 2018.

16. "SAIC Moves Corporate Headquarters to McLean, Virginia" Archived October 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

17. Paul McDougall (March 15, 2012). "SAIC Pays $500 Million In Record Settlement With NYC". InformationWeek. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

18. Calder, Rich (April 29, 2014). "CityTime head, accomplices sentenced to 20 years in prison". New York Post. Retrieved May 14, 2014.

19. Censer, Marjorie (August 30, 2012). "SAIC to split into two public companies". Washington Post. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

20. "SAIC, Inc. (SAI) to Spin Off Services Business". streetinsider.com. September 9, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

21. Censer, Marjorie (November 5, 2012). "When SAIC splits, Jumper and Moraco will head companies". Washington Post. Retrieved April 15, 2014.

22. Censer, Marjorie (March 3, 2013). "SAIC to name technology business Leidos". Washington Post. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

23. Censer, Marjorie (February 25, 2013). "SAIC to name solutions business Leidos". Washington Post. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

24. SAIC (August 12, 2013). "Leidos Headquarters To Be In Reston, VA" (Press release). PR Newswire. Retrieved August 15, 2013.

25. SEC Edgar database

26. SAIC. "Industry Rankings". Archived from the original on August 2, 2013. Retrieved August 9,2013.

27. "Leidos Deal Closes, Spawning Vast Solutions Enterprise". Retrieved August 23, 2016.

28. "Leidos Holdings". Fortune.

29. "Leidos completes acquisition of Dynetics, expanding company's portfolio with new offerings and technical capabilities" (Press release). Leidos. January 31, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

30. Thompson, Loren. "Leidos Discovers Its Business Model Adapts Surprisingly Well To Coronavirus". Forbes. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

31. Pound, Jesse (March 7, 2020). "Analysts say the coronavirus outbreak won't hurt the stock that Stifel calls 'The Terminator'". CNBC. Retrieved April 24, 2020.

32. "Defense & Intelligence". Leidos. Retrieved June 24, 2017.

33. "Leidos Announces Roger A. Krone As CEO". wspa.com. July 1, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

34. "Leadership Leidos.com". Retrieved February 13, 2019.

35. "SAIC Names Dahlberg New CEO". Wall Street Journal. October 7, 2003. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

36. Censer, Marjorie (August 30, 2012). "SAIC to split into two public companies". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 8, 2013.

37. "Leidos Announces Move to New Headquarters Facility in Reston Town Center". Leidos Holdings, Inc. January 30, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

38. Sernovitz, Daniel J. (January 30, 2018). "Leidos to merge workforces into new headquarters space". Washington Business Journal. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

39. Waseem, Fatimah (April 30, 2020). "Boston Properties Reports Strong Leasing Activity Despite COVID-19". Reston Now. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

40. Patience Wait (October 21, 2002). "SAIC team gets demonstration phase of Trailblazer". Washington Technology. Archived from the original on March 2, 2008.

41. "NSA datamining pushes tech envelope". PhysOrg.com. May 25, 2006.

42. Martin Sieff (August 18, 2005). "NSA's New Boss Puts Faith In Hi Tech Fixes". Space War.

43. "After Olympics contractors leave behind IT legacy". Washington Technology. Archived from the original on May 6, 2006. Retrieved August 13, 2006.

44. Eggen, Dan; Witte, Griff (August 18, 2006). "The FBI's Upgrade That Wasn't". Washington Post. Retrieved February 8, 2007.

45. "top-100-lists 2013". Washington Technology, info business for government contractors. June 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

46. "Leidos Subsidiaries". Leidos. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

47. "Companies". Leidos. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

48. "Reveal CT-800 Baggage Inspection System". Retrieved December 19, 2013.

49. "R. W. Beck Is Now SAIC Energy, Environment & Infrastructure, LLC". Archived from the originalon April 4, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

50. "Science Applications International Corporation vs. Comptroller of the Treasury" (PDF). txcrt.state.md.us. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 28, 2008. Retrieved April 17, 2008.

51. "Company History". networksolutions.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved March 29, 2008.

52. Wilkers, Ross. "Leidos closes sale of commercial cyber business -". Washington Technology. Retrieved February 20, 2020.

53. The Center for Responsive Politics. http://www.opensecrets.org/orgs/summary.php?id=D000000369a. Accessed 6/9/13.

54. "Lobbyists representing Leidos Inc, 2013". Open secrets.org. Retrieved February 27, 2014.

55. "FEDERAL BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION'S INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY MODERNIZATION PROGRAM, TRILOGY". Retrieved February 14, 2019.

56. "Robert S. Mueller, III, Director of FBI Appropriations Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, State and the Judicial". FBI. February 3, 2005. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

57. "SAIC Says FBI Should Deploy its Software". SignOnSanDiego.com. Retrieved September 18,2008.

58. The Center for Responsive politics. http://www.opensecrets.org/orgs/summary.php?id=D000000369a. Accessed 6/9/13.

59. Capaccio, Anthony (May 2, 2018). "Leidos's Treatment of Female Whistle-Blower Gets Pentagon Review". Bloomberg News. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

Further reading

· The SAIC Solution: How We Built an $8 Billion Employee-Owned Technology Company 1st Edition by Dr. J. Robert Beyster

· Official website

· Coverage of SAIC Iraq Single-source contracts

· Washington's $8 Billion Shadow (Vanity Fair Magazine, March 2007)

· Exposé: America's Investigative Reports episode on SAIC from 10/07/2007

External links

Official website

· Business data for Leidos:

o Google Finance

o Yahoo! Finance

o Bloomberg

o Reuters

o SEC filings