Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Fosco Maraini

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/29/20

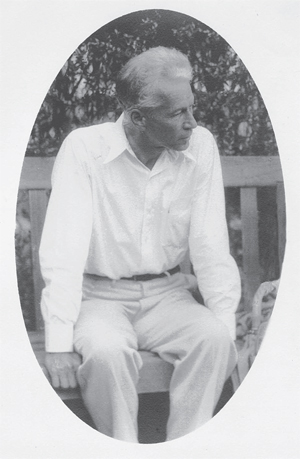

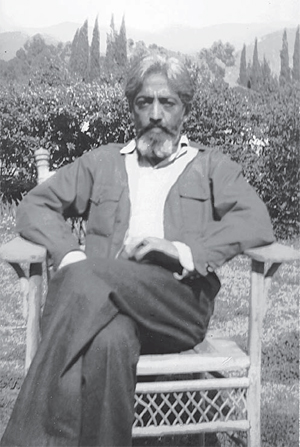

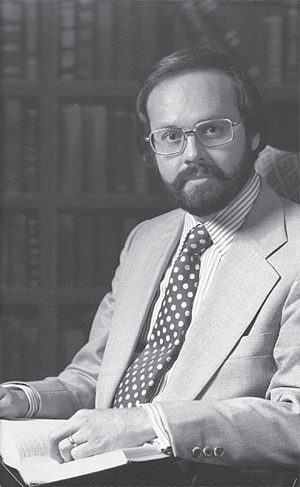

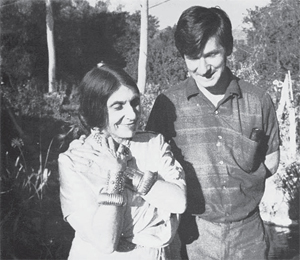

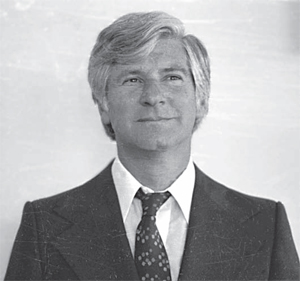

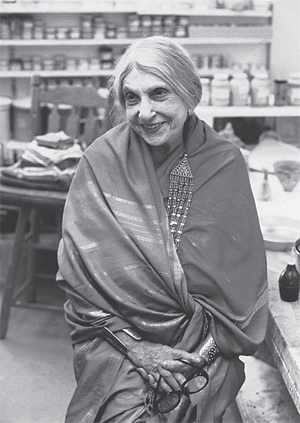

Fosco Maraini

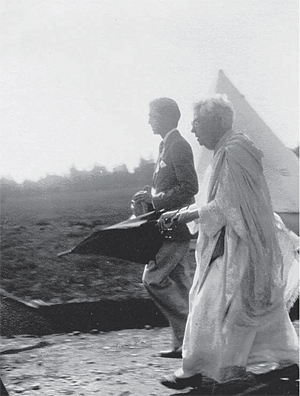

Fosco Maraini (on the left)

Born: 15 November 1912, Florence, Italy

Died: 8 June 2004 (aged 91), Florence, Italy

Nationality: Italian

Known for Metasemantic poetry

Spouse(s): Topazia Alliata (m. 1935; div. 1970); Mieko Namiki (m. 1970; his death 2004)

Children: Dacia Maraini; Toni Maraini; Yuki Maraini

Scientific career

Fields: Ethnology of Tibet and Japan

Influences: Giuseppe Tucci

Fosco Maraini (Italian: [ˈfosko maraˈiːni; ˈfɔs-]; 15 November 1912 – 8 June 2004) was an Italian photographer, anthropologist, ethnologist, writer, mountaineer and academic.

Biography

He was born in Florence from the Italian sculptor Antonio Maraini (1886-1963) and Cornelia Edith "Yoï" Crosse also known as Yoï Crosse-Pawlowska (1877-1944), a model and writer of English and Polish descent who was born in Tállya, Hungary. As a photographer, Fosco Maraini is perhaps best known for his work in Tibet and Japan. The visual record Maraini captured in images of Tibet and on the Ainu people of Hokkaidō has gained significance as historical documentation of two disappearing cultures. His work was recognized with a 2002 award from the Photographic Society of Japan, citing his fine-art photos—and especially his impressions of Hokkaido's Ainu. The society also acknowledged his efforts to strengthen ties between Japan and Italy over 60 years. Maraini also photographed extensively in the Karakoram and Hindu Kush mountain ranges of Central Asia, in Southeast Asia and in the southern regions of his native Italy.

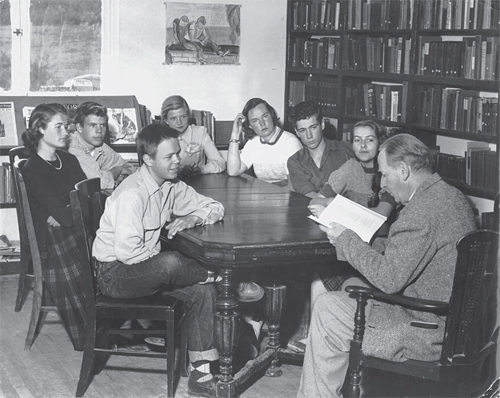

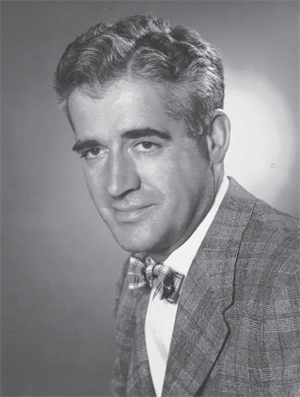

Members of the Italian Gasherbrum IV expedition 1958, Maraini is standing, second from right

As an anthropologist and ethnographer, he is known especially for his published observations and accounts of his travels with Tibetologist Giuseppe Tucci during two expeditions to Tibet, first in 1937 and again in 1948.[1]

As a mountaineer, he is perhaps best known for the 1959 ascent of Saraghrar[2] and for his published accounts of this and other Himalayan climbs.[3] As a climber in the Himalayas, he was moved to describe it as "the greatest museum of shape and form on earth."[4]

From 1938 to 1943, Maraini's academic career progressed in Japan, teaching first in Hokkaido (1938–1941) and then in Kyoto (1941–1943); but what he himself observed and learned during those years may be more important than what he may have taught. Dacia, his eldest daughter, would decades later recall that "the first trip I took was on the sea from Brindisi to Kobe."[5] Two of his three daughters were born in Japan: Yuki (registered as Luisa in Italy) was born in Sapporo in 1939, Antonella (Toni) in Tokyo in 1941. After the Italians signed an armistice with the allies in World War II, the Japanese authorities asked Maraini and his wife Topazia Alliata to sign an act of allegiance to Mussolini's puppet Republic of Salò. They were both asked separately and separately they refused, and were interned with their three daughters of six, four and two years old in a concentration camp at Nagoya for two years.[6] Those memories of 1943 through 1946 evolved into some chapters of the book "Meeting with Japan" by Fosco Maraini. Dacia Maraini's collection of poetry drawn from those difficult years, Mangiami pure, was published in 1978.[7]

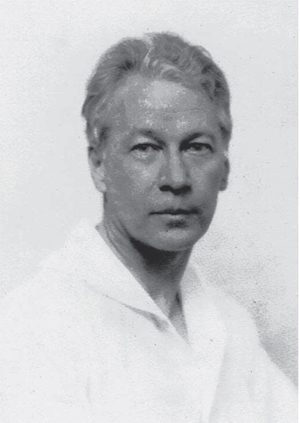

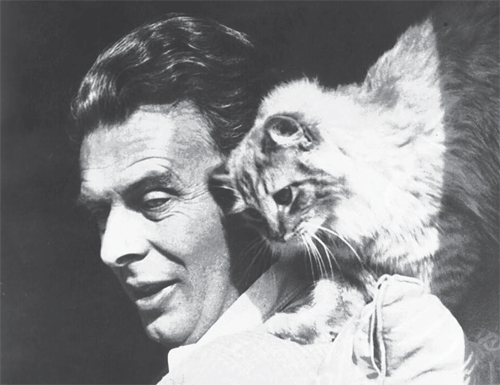

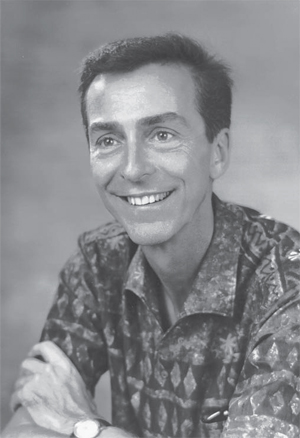

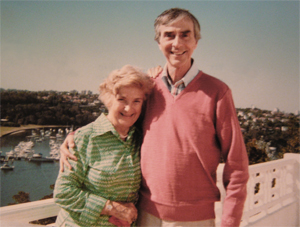

Fosco Maraini, his wife Mieko Namiki and Kurt Diemberger

The Maraini family retreated to Italy after the Allies occupied Japan. This period became the core of another book by Dacia Maraini who remembers that they left Asia "without either money or possessions, stripped bare, with nothing on our backs except the clothes handed out by the American military."[8] The years in Italy are described in the book, Bagheria, named after the Sicilian town not far from Palermo where the family lived.[8]

In time, Maraini did return to his "adopted homeland" of Japan; and in 1955, this journey of rediscovery became the basis for his book, Meeting with Japan.[9]

In an interview, one of his daughters explained that one of her earliest memories of her father speaking is when he claimed:

The head of the Tuscany regional government publicly explained that Maraini had "honored Florence and the Tuscany by teaching us to be tolerant of other cultures."[10]

Fosco Maraini was, with Giuliana Stramigioli among others, a founding member of the AISTUGIA – the Italian Association for the Japanese Studies.

The 1963 film Violated Paradise, directed by Marion Gering was based on Maraini's work L' Isola Delle Pescatrici (1960).[11] A few images shot by Maraini's crew were used in the production.[12]

Selected works

Maraini has had numerous photographic exhibitions in Europe and Japan; and he wrote over twenty books, many of which have been translated into several languages.

This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

Books

• Secret Tibet (1952)

• Ore Giapponesi (1959)

• G4-Karakorum (1959)

• Meeting with Japan (1960)

• L'Isola delle Pescatrici (1960)

• Paropàmiso (1963). English version: Where Four Worlds Meet: Hindu Kush 1959 (1964)

• Tokyo (1976), Photography by Harald Sund; The Great Cities Time Life Books Amsterdam.[13]

• The Island of the Fisherwomen (1962)

• Jerusalem: Rock of Ages (1969), Photography by Alfred Bernheim and Ricarda Schwerin; Translated by Judith Landry; New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc.

• Patterns of Continuity (1971)

• Gnosi delle Fànfole (1994)

• Nuvolario (1995)

• Case, amori, universi (2000)

Articles

• "Tradition and Innovation in Japanese Films," Geographical Magazine. Oct. 1954: 294–305.

Honors

• Photographic Society of Japan, International Award—2002.[14]

• Japan Foundation Award—1986,[15]

• Order of the Rising Sun, 3rd class—1982.[16]

• International Society to Save Kyoto's Historic Environment, (ISSK) – First Honorary President.

See also

• Saraghrar

• Topazia Alliata

• Dacia Maraini

• Marilyn Silverstone

Notes:

1. Maraini, Fosco. (1994). "Tibet in 1937 and 1948," Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Government of Tibet in Exile web site.

2. Carlo Pinelli, fellow climber in 1959. Mountain Wilderness web site.

3. Karakorum, K-2 climb Archived 17 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

4. trekker web page Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, just one example of the oft-repeated Maraini quote.

5. Centovalli, Benedetta. (2005). "Interview, Dacia Maraini", Words without Borders web site.

6. Maraini bio note. Life in Legacy web site.

7. Dacia Maraini (1936), bio. Italia Donna web site (in Italian).

8. Marcus, James. " Broken Promises," New York Times. 9 April 1995.

9. "From Sukiyaki to Storippu," Time. 4 January 1960.

10. "Il gonfalone della Toscana a Dacia Maraini in memoria del padre scomparso," Servizi radiofonici Regione Toscana. 8 June 2004.

11. Goble, Alan (1999). The Complete Index to Literary Sources in Film. Walter de Gruyter. p. 306. ISBN 978-3-11-095194-3.

12. "l isola delle pescatrici" [The Island of the Fisherwomen] (in Italian). Asiatica Film Mediale. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

13. Maraini, Fosco. (1976). "The Great Cities: Tokyo" Time-Life: The Great Cities.

14. PhotoHistory 2002.

15. Japan Foundation Awards (1986) Archived 11 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

16. Rogala, Jozef. A Collector's Guide to Books on Japan in English: A Select List of Over 2500 Titles with Subject Index, p. 144.

References

• Lane, John Francis. Obituary, "Fosco Maraini, Italian Explorer and Travel Writer Who Brought His Understanding of the East to the West," The Guardian (Manchester). 15 June 2004.

• Obituary, "Fosco Maraini, Writer and Traveller Who Photographed 'Secret Tibet'," The Independent (London). 19 June 2004.

• Obituary, "Fosco Maraini: Dauntless Italian travel writer who devoted himself to exploring Asian civilisations, and once lopped off a finger to prove his courage," Times (London). 29 June 2004.

• Rogala, Jozef. (2001). A Collector's Guide to Books on Japan in English: A Select List of Over 2500 Titles with Subject Index. London: Routledge. ISBN 1-873410-80-8

External links

• Official website

• Dacia Mariani website (in Italian)

o Dacia Maraini's bio (in Italian)—referencing father

o Dacia Maraini's bio (in English)—referencing father

• Toni Maraini's bio (in Italian)—daughter's bio, referencing father

• Marilyn Silverstone—photographer influenced by Maraini

• Japan Mint: 2004 International Coin Design Competition – see competitor design, "Homage to Fosco Maraini, famous Italian anthropologist, orientalist, writer and photographer"... also see "Excellent Work" plaster model, Maurizio Sacchetti (designer)

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/29/20

Fosco Maraini

Fosco Maraini (on the left)

Born: 15 November 1912, Florence, Italy

Died: 8 June 2004 (aged 91), Florence, Italy

Nationality: Italian

Known for Metasemantic poetry

Metasemantic poetry (from the Greek μετά "after" and σημαντικός "significant") is a literary technique theorized and used by Fosco Maraini in his collection of poems "Gnòsi delle fànfole" of 1978.

While semantics is that part of linguistics that studies the meaning of words (lexical semantics), of the sets of words, of phrases (phrasal semantics), and of texts, metasemantics, in the sense given by the Maraini, goes beyond the meaning of words and consists of the use, within the text, of words without meaning, but having a familiar sound to the language to which the text itself belongs, and which must still follow the syntactical and grammatical rules (in the case of Fosco Maraini, the Italian language). One can attribute more or less arbitrary meanings to these words by their sound and their position within the text.

A language similar to this technique, mostly defined as nonsense, was also used by Lewis Carroll in his poem Jabberwocky published in 1871.

Other examples of proto-metasemantic expressions in the English language date back to the beginning of 16th century with the onomatopoeic sounds typical of gibberish.

The most famous example of metasemantic poetry, in the original meaning of the term as given by Maraini, is his poem Il Lonfo, also known for the recitation made by Gigi Proietti in 2005 (in the transmission of Renzo Arbore Speciale per me - meno siamo meglio stiamo / Special for me - the less we are, the better we are), as well as for its recitation in the episode on February 7, 2007 the program Parla con me (Talk to Me), conducted on Rai 3 by Serena Dandin

-- Metasemantic poetry, by Wikipedia

Spouse(s): Topazia Alliata (m. 1935; div. 1970); Mieko Namiki (m. 1970; his death 2004)

Children: Dacia Maraini; Toni Maraini; Yuki Maraini

Scientific career

Fields: Ethnology of Tibet and Japan

Influences: Giuseppe Tucci

Fosco Maraini (Italian: [ˈfosko maraˈiːni; ˈfɔs-]; 15 November 1912 – 8 June 2004) was an Italian photographer, anthropologist, ethnologist, writer, mountaineer and academic.

Biography

He was born in Florence from the Italian sculptor Antonio Maraini (1886-1963) and Cornelia Edith "Yoï" Crosse also known as Yoï Crosse-Pawlowska (1877-1944), a model and writer of English and Polish descent who was born in Tállya, Hungary. As a photographer, Fosco Maraini is perhaps best known for his work in Tibet and Japan. The visual record Maraini captured in images of Tibet and on the Ainu people of Hokkaidō has gained significance as historical documentation of two disappearing cultures. His work was recognized with a 2002 award from the Photographic Society of Japan, citing his fine-art photos—and especially his impressions of Hokkaido's Ainu. The society also acknowledged his efforts to strengthen ties between Japan and Italy over 60 years. Maraini also photographed extensively in the Karakoram and Hindu Kush mountain ranges of Central Asia, in Southeast Asia and in the southern regions of his native Italy.

Members of the Italian Gasherbrum IV expedition 1958, Maraini is standing, second from right

As an anthropologist and ethnographer, he is known especially for his published observations and accounts of his travels with Tibetologist Giuseppe Tucci during two expeditions to Tibet, first in 1937 and again in 1948.[1]

It was not just the ideologists and theoreticians of national socialism who were closely concerned with Tibet, but also high-ranking intellectuals and scholars closely linked to Italian fascism. First of all, Giuseppe Tucci, who attempted to combine Eastern and fascist ideas with one another, must be mentioned (Benavides 1995).

-- The Shadow of the Dalai Lama: Sexuality, Magic and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism, by Victor and Victoria Trimondi

In 1933 he promoted the foundation the Italian Institute for the Middle and Far East [it] - IsMEO (Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente), based in Rome. The IsMEO was established as a "Moral body directly depending on Mussolini"...

Tucci officially visited Japan for the first time in November 1936, and remained there for over two months until January 1937, when he attended at the opening of the Italian-Japanese Institute (Istituto Italo-nipponico) in Tokyo. Tucci traveled all over Japan giving lectures on Tibet and "racial purity"....

Tucci was a supporter of Italian Fascism and Benito Mussolini. His activity under Il Duce started with Giovanni Gentile, at the time Professor of the History of Philosophy at the University of Rome and already close friend and collaborator of Mussolini, when Tucci was studying at the university of Rome, and went on until the Gentile killing, and the compulsory administration of IsMEO for over two years until 1947.Gentile became a member of the Fascist Grand Council in 1925, and remained loyal to Mussolini even after the fall of the Fascist government in 1943. He supported Mussolini's establishment of the "Republic of Salò", a puppet state of Nazi Germany, despite having criticized its anti-Jewish laws, and accepted an appointment in its government. Gentile was the last president of the Royal Academy of Italy (1943–1944).

In 1944 a group of anti-fascist partisans, led by Bruno Fanciullacci, murdered the "philosopher of Fascism" as he returned from the prefecture in Florence, where he had been arguing for the release of anti-fascist intellectuals. Gentile was buried in the church of Santa Croce in Florence.

-- Giovanni Gentile, by Wikipedia

In November 1936 - January 1937 he was the representative of Mussolini in Japan, where he was sent to improve the diplomatic relations between Italy and Japan and to make Fascist propaganda. On 27 April 1937 he gave a speech on the radio in Japanese on Mussolini's behalf. In this country his strong and tireless action paved the way to the inclusion of Italy to the Anti-Comintern Pact (6 November 1937). He wrote popular articles for the Italian state that decried the rationalism of industrialized 1930s-1940s Europe and yearned for an authentic existence in touch with nature, that he claimed could be found in Asia. According to Tibetologist Donald S. Lopez, "For Tucci, Tibet was an ecological paradise and timeless utopia into which industrialized Europe figuratively could escape and find peace, a cure for western ills, and from which Europe could find its own pristine past to which to return."

-- Giuseppe Tucci, by Wikipedia

As a mountaineer, he is perhaps best known for the 1959 ascent of Saraghrar[2] and for his published accounts of this and other Himalayan climbs.[3] As a climber in the Himalayas, he was moved to describe it as "the greatest museum of shape and form on earth."[4]

From 1938 to 1943, Maraini's academic career progressed in Japan, teaching first in Hokkaido (1938–1941) and then in Kyoto (1941–1943); but what he himself observed and learned during those years may be more important than what he may have taught. Dacia, his eldest daughter, would decades later recall that "the first trip I took was on the sea from Brindisi to Kobe."[5] Two of his three daughters were born in Japan: Yuki (registered as Luisa in Italy) was born in Sapporo in 1939, Antonella (Toni) in Tokyo in 1941. After the Italians signed an armistice with the allies in World War II, the Japanese authorities asked Maraini and his wife Topazia Alliata to sign an act of allegiance to Mussolini's puppet Republic of Salò. They were both asked separately and separately they refused, and were interned with their three daughters of six, four and two years old in a concentration camp at Nagoya for two years.[6] Those memories of 1943 through 1946 evolved into some chapters of the book "Meeting with Japan" by Fosco Maraini. Dacia Maraini's collection of poetry drawn from those difficult years, Mangiami pure, was published in 1978.[7]

Fosco Maraini, his wife Mieko Namiki and Kurt Diemberger

The Maraini family retreated to Italy after the Allies occupied Japan. This period became the core of another book by Dacia Maraini who remembers that they left Asia "without either money or possessions, stripped bare, with nothing on our backs except the clothes handed out by the American military."[8] The years in Italy are described in the book, Bagheria, named after the Sicilian town not far from Palermo where the family lived.[8]

In time, Maraini did return to his "adopted homeland" of Japan; and in 1955, this journey of rediscovery became the basis for his book, Meeting with Japan.[9]

In an interview, one of his daughters explained that one of her earliest memories of her father speaking is when he claimed:

Remember that races don't exist, cultures exist.[5]

The head of the Tuscany regional government publicly explained that Maraini had "honored Florence and the Tuscany by teaching us to be tolerant of other cultures."[10]

Fosco Maraini was, with Giuliana Stramigioli among others, a founding member of the AISTUGIA – the Italian Association for the Japanese Studies.

The 1963 film Violated Paradise, directed by Marion Gering was based on Maraini's work L' Isola Delle Pescatrici (1960).[11] A few images shot by Maraini's crew were used in the production.[12]

Selected works

Maraini has had numerous photographic exhibitions in Europe and Japan; and he wrote over twenty books, many of which have been translated into several languages.

This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

Books

• Secret Tibet (1952)

• Ore Giapponesi (1959)

• G4-Karakorum (1959)

• Meeting with Japan (1960)

• L'Isola delle Pescatrici (1960)

• Paropàmiso (1963). English version: Where Four Worlds Meet: Hindu Kush 1959 (1964)

• Tokyo (1976), Photography by Harald Sund; The Great Cities Time Life Books Amsterdam.[13]

• The Island of the Fisherwomen (1962)

• Jerusalem: Rock of Ages (1969), Photography by Alfred Bernheim and Ricarda Schwerin; Translated by Judith Landry; New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, Inc.

• Patterns of Continuity (1971)

• Gnosi delle Fànfole (1994)

• Nuvolario (1995)

• Case, amori, universi (2000)

Articles

• "Tradition and Innovation in Japanese Films," Geographical Magazine. Oct. 1954: 294–305.

Honors

• Photographic Society of Japan, International Award—2002.[14]

• Japan Foundation Award—1986,[15]

• Order of the Rising Sun, 3rd class—1982.[16]

• International Society to Save Kyoto's Historic Environment, (ISSK) – First Honorary President.

See also

• Saraghrar

• Topazia Alliata

• Dacia Maraini

• Marilyn Silverstone

Notes:

1. Maraini, Fosco. (1994). "Tibet in 1937 and 1948," Archived 13 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine Government of Tibet in Exile web site.

2. Carlo Pinelli, fellow climber in 1959. Mountain Wilderness web site.

3. Karakorum, K-2 climb Archived 17 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

4. trekker web page Archived 13 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, just one example of the oft-repeated Maraini quote.

5. Centovalli, Benedetta. (2005). "Interview, Dacia Maraini", Words without Borders web site.

6. Maraini bio note. Life in Legacy web site.

7. Dacia Maraini (1936), bio. Italia Donna web site (in Italian).

8. Marcus, James. " Broken Promises," New York Times. 9 April 1995.

9. "From Sukiyaki to Storippu," Time. 4 January 1960.

10. "Il gonfalone della Toscana a Dacia Maraini in memoria del padre scomparso," Servizi radiofonici Regione Toscana. 8 June 2004.

11. Goble, Alan (1999). The Complete Index to Literary Sources in Film. Walter de Gruyter. p. 306. ISBN 978-3-11-095194-3.

12. "l isola delle pescatrici" [The Island of the Fisherwomen] (in Italian). Asiatica Film Mediale. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

13. Maraini, Fosco. (1976). "The Great Cities: Tokyo" Time-Life: The Great Cities.

14. PhotoHistory 2002.

15. Japan Foundation Awards (1986) Archived 11 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

16. Rogala, Jozef. A Collector's Guide to Books on Japan in English: A Select List of Over 2500 Titles with Subject Index, p. 144.

References

• Lane, John Francis. Obituary, "Fosco Maraini, Italian Explorer and Travel Writer Who Brought His Understanding of the East to the West," The Guardian (Manchester). 15 June 2004.

• Obituary, "Fosco Maraini, Writer and Traveller Who Photographed 'Secret Tibet'," The Independent (London). 19 June 2004.

• Obituary, "Fosco Maraini: Dauntless Italian travel writer who devoted himself to exploring Asian civilisations, and once lopped off a finger to prove his courage," Times (London). 29 June 2004.

• Rogala, Jozef. (2001). A Collector's Guide to Books on Japan in English: A Select List of Over 2500 Titles with Subject Index. London: Routledge. ISBN 1-873410-80-8

External links

• Official website

• Dacia Mariani website (in Italian)

o Dacia Maraini's bio (in Italian)—referencing father

o Dacia Maraini's bio (in English)—referencing father

• Toni Maraini's bio (in Italian)—daughter's bio, referencing father

• Marilyn Silverstone—photographer influenced by Maraini

• Japan Mint: 2004 International Coin Design Competition – see competitor design, "Homage to Fosco Maraini, famous Italian anthropologist, orientalist, writer and photographer"... also see "Excellent Work" plaster model, Maurizio Sacchetti (designer)