Part 2 of 2

Second marriage Ambedkar with wife Savita in 1948

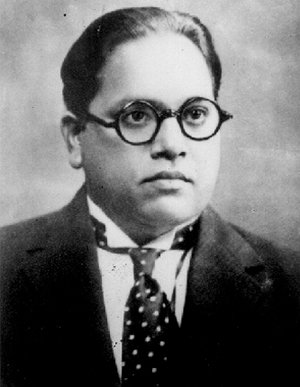

Ambedkar with wife Savita in 1948Ambedkar's first wife Ramabai died in 1935 after a long illness. After completing the draft of India's constitution in the late 1940s, he suffered from lack of sleep, had neuropathic pain in his legs, and was taking insulin and homoeopathic medicines. He went to Bombay for treatment, and there met Dr. Sharada Kabir, whom he married on 15 April 1948, at his home in New Delhi. Doctors recommended a companion who was a good cook and had medical knowledge to care for him.[99] She adopted the name Savita Ambedkar and cared for him the rest of his life.[100] Savita Ambedkar, who was called 'Mai', died on May 29, 2003, aged 93 at Mehrauli, New Delhi.[101]

Conversion to BuddhismMain article: Dalit Buddhism

Ambedkar delivering speech during mass conversion

Ambedkar delivering speech during mass conversionAmbedkar considered converting to Sikhism, which encouraged opposition to oppression and so appealed to leaders of scheduled castes. But after meeting with Sikh leaders, he concluded that he might get "second-rate" Sikh status.[102]

Instead, around 1950, he began devoting his attention to Buddhism and travelled to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) to attend a meeting of the World Fellowship of Buddhists.[103] While dedicating a new Buddhist vihara near Pune, Ambedkar announced he was writing a book on Buddhism, and that when it was finished, he would formally convert to Buddhism.[104] He twice visited Burma in 1954; the second time to attend the third conference of the World Fellowship of Buddhists in Rangoon.[105] In 1955, he founded the Bharatiya Bauddha Mahasabha, or the Buddhist Society of India.[106] He completed his final work, The Buddha and His Dhamma, in 1956 which was published posthumously.[106]

After meetings with the Sri Lankan Buddhist monk Hammalawa Saddhatissa,[107] Ambedkar organised a formal public ceremony for himself and his supporters in Nagpur on 14 October 1956. Accepting the Three Refuges and Five Precepts from a Buddhist monk in the traditional manner, Ambedkar completed his own conversion, along with his wife. He then proceeded to convert some 500,000 of his supporters who were gathered around him.[104][108] He prescribed the 22 Vows for these converts, after the Three Jewels and Five Precepts. He then travelled to Kathmandu, Nepal to attend the Fourth World Buddhist Conference.[105] His work on The Buddha or Karl Marx and "Revolution and counter-revolution in ancient India" remained incomplete.

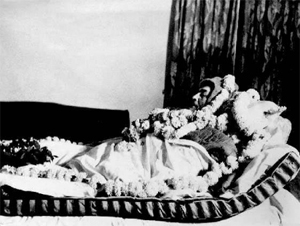

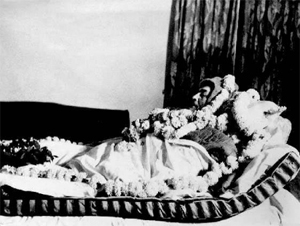

Death Mahaparinirvana of B. R. Ambedkar

Mahaparinirvana of B. R. AmbedkarSince 1948, Ambedkar suffered from diabetes. He was bed-ridden from June to October in 1954 due to medication side-effects and poor eyesight.[104] His health worsened during 1955. Three days after completing his final manuscript The Buddha and His Dhamma, Ambedkar died in his sleep on 6 December 1956 at his home in Delhi.

A Buddhist cremation was organised at Dadar Chowpatty beach on 7 December,[109] attended by half a million grieving people.[110] A conversion program was organised on 16 December 1956,[111] so that cremation attendees were also converted to Buddhism at the same place.[111]

Ambedkar was survived by his second wife, who died in 2003,[112] and his son Yashwant (known as Bhaiyasaheb Ambedkar).[113] Ambedkar's grandson, Ambedkar Prakash Yashwant, is the chief-adviser of the Buddhist Society of India,[114] leads the Bharipa Bahujan Mahasangh[115] and has served in both houses of the Indian Parliament.[115]

A number of unfinished typescripts and handwritten drafts were found among Ambedkar's notes and papers and gradually made available. Among these were Waiting for a Visa, which probably dates from 1935–36 and is an autobiographical work, and the Untouchables, or the Children of India's Ghetto, which refers to the census of 1951.[104]

A memorial for Ambedkar was established in his Delhi house at 26 Alipur Road. His birthdate is celebrated as a public holiday known as Ambedkar Jayanti or Bhim Jayanti. He was posthumously awarded India's highest civilian honour, the Bharat Ratna, in 1990.[116]

On the anniversary of his birth and death, and on Dhamma Chakra Pravartan Din (14 October) at Nagpur, at least half a million people gather to pay homage to him at his memorial in Mumbai.[117] Thousands of bookshops are set up, and books are sold. His message to his followers was "educate, agitate, organise!".[118]

Legacy People paying tribute at the central statue of Ambedkar in Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University in Aurangabad.

People paying tribute at the central statue of Ambedkar in Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Marathwada University in Aurangabad.Ambedkar's legacy as a socio-political reformer, had a deep effect on modern India.[119][120] In post-Independence India, his socio-political thought is respected across the political spectrum. His initiatives have influenced various spheres of life and transformed the way India today looks at socio-economic policies, education and affirmative action through socio-economic and legal incentives. His reputation as a scholar led to his appointment as free India's first law minister, and chairman of the committee for drafting the constitution. He passionately believed in individual freedom and criticised caste society. His accusations of Hinduism as being the foundation of the caste system made him controversial and unpopular among Hindus.[121] His conversion to Buddhism sparked a revival in interest in Buddhist philosophy in India and abroad.[122]

Many public institutions are named in his honour, and the Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International Airport in Nagpur, otherwise known as Sonegaon Airport. Dr. B. R. Ambedkar National Institute of Technology, Jalandhar, Ambedkar University Delhi is also named in his honour.

The Maharashtra government has acquired a house in London where Ambedkar lived during his days as a student in the 1920s. The house is expected to be converted into a museum-cum-memorial to Ambedkar.[123]

Ambedkar was voted "the Greatest Indian" in 2012 by a poll which didn't include Mahatma Gandhi, citing it was not possible to beat him in the poll. The poll was organised by History TV18 and CNN IBN. Nearly 20 million votes were cast.[124] Due to his role in economics, Narendra Jadhav, a notable Indian economist,[125] has said that Ambedkar was "the highest educated Indian economist of all times."[126] Amartya Sen, said that Ambedkar is "father of my economics", and "he was highly controversial figure in his home country, though it was not the reality. His contribution in the field of economics is marvelous and will be remembered forever."[127][128]

Ambedkar's legacy was not without criticism. Ambedkar has been criticised for his one-sided views on the issue of caste at the expense of cooperation with the larger nationalist movement.[129] Ambedkar has been also criticised by some of his biographers over his neglect of organization-building.[130]

Ambedkar's political philosophy has given rise to a large number of political parties, publications and workers' unions that remain active across India, especially in Maharashtra. His promotion of Buddhism has rejuvenated interest in Buddhist philosophy among sections of population in India. Mass conversion ceremonies have been organised by human rights activists in modern times, emulating Ambedkar's Nagpur ceremony of 1956.[131] Some Indian Buddhists regard him as a Bodhisattva, although he never claimed it himself.[132] Outside India, during the late 1990s, some Hungarian Romani people drew parallels between their own situation and that of the downtrodden people in India. Inspired by Ambedkar, they started to convert to Buddhism.[133]

In popular cultureSeveral movies, plays, and other works have been based on the life and thoughts of Ambedkar. Jabbar Patel directed the English-language film Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar in 2000 with Mammootty in the lead role.[134] This biopic was sponsored by the National Film Development Corporation of India and the government's Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment. The film was released after a long and controversial gestation.[135] David Blundell, professor of anthropology at UCLA and historical ethnographer, has established Arising Light – a series of films and events that are intended to stimulate interest and knowledge about the social conditions in India and the life of Ambedkar.[136] In Samvidhaan,[137] a TV mini-series on the making of the Constitution of India directed by Shyam Benegal, the pivotal role of B. R. Ambedkar was played by Sachin Khedekar. The play Ambedkar Aur Gandhi, directed by Arvind Gaur and written by Rajesh Kumar, tracks the two prominent personalities of its title.[138]

Bhimayana: Experiences of Untouchability is a graphic biography of Ambedkar created by Pardhan-Gond artists Durgabai Vyam and Subhash Vyam, and writers Srividya Natarajan and S. Anand. The book depicts the experiences of untouchability faced by Ambedkar from childhood to adulthood. CNN named it one of the top 5 political comic books.[139]

The Ambedkar Memorial at Lucknow is dedicated in his memory. The chaitya consists of monuments showing his biography.[140][141]

Jai Bhim slogan was given by the dalit community in Delhi in his honour on 1946.

Google commemorated Ambedkar's 124th birthday through a homepage doodle[142] on 14 April 2015.[143] The doodle was featured in India, Argentina, Chile, Ireland, Peru, Poland, Sweden and the United Kingdom.[144][145][146]

A television show named Ek Mahanayak: Dr. B. R. Ambedkar portraying his life aired on &TV in 2019.[147]

WorksThe Education Department, Government of Maharashtra (Mumbai) published the collection of Ambedkar's writings and speeches in different volumes.[148]

· Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development and 11 Other Essays

· Ambedkar in the Bombay Legislature, with the Simon Commission and at the Round Table Conferences, 1927–1939

· Philosophy of Hinduism; India and the Pre-requisites of Communism; Revolution and Counter-revolution; Buddha or Karl Marx

· Riddles in Hinduism

· Essays on Untouchables and Untouchability

· The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India

· The Untouchables Who Were They And Why They Became Untouchables ?

· The Annihilation of Caste (1936)

· Pakistan or the Partition of India

· What Congress and Gandhi have done to the Untouchables; Mr. Gandhi and the Emancipation of the Untouchables

· Ambedkar as member of the Governor General's Executive Council, 1942–46

· The Buddha and his Dhamma

· Unpublished Writings; Ancient Indian Commerce; Notes on laws; Waiting for a Visa ; Miscellaneous notes, etc.

· Ambedkar as the principal architect of the Constitution of India

· (2 parts) Dr. Ambedkar and The Hindu Code Bill

· Ambedkar as Free India's First Law Minister and Member of Opposition in Indian Parliament (1947–1956)

· The Pali Grammar

· Ambedkar and his Egalitarian Revolution – Struggle for Human Rights. Events starting from March 1927 to 17 November 1956 in the chronological order; Ambedkar and his Egalitarian Revolution – Socio-political and religious activities. Events starting from November 1929 to 8 May 1956 in the chronological order; Ambedkar and his Egalitarian Revolution – Speeches. (Events starting from 1 January to 20 November 1956 in the chronological order.)

See also· Chaitya Bhoomi

· Deekshabhoomi

· Statue of Equality

References1. Sabha, Rajya. "Alphabetical List of All Members of Rajya Sabha Since 1952". Rajya Sabha Secretariat. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Serial Number 69 in the list

2. "Attention BJP: When the Muslim League rescued Ambedkar from the 'dustbin of history'". Firstpost. 15 April 2015. Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015. Cite error: The named reference "Firstpost 2015" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

3.

https://rajyasabhahindi.nic.in/rshindi/ ... y_main.asp4. Sadangi, Himansu Charan (13 August 2008). "Emancipation of Dalits and Freedom Struggle". Gyan Publishing House – via Google Books.

5. Keer, Dhananjay (13 August 1971). "Dr. Ambedkar: Life and Mission". Popular Prakashan – via Google Books.

6. Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 5. ISBN 1850654492. Cite error: The named reference "autogenerated2" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

7. Khairmode, Changdev Bhawanrao (1985). Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (Vol. 7) (in Marathi). Mumbai: Maharashtra Rajya Sahilya Sanskruti Mandal, Matralaya. p. 245.

8. Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1850654490.

9. Khairmode, Changdev Bhawanrao (1985). Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (Vol. 7) (in Marathi). Mumbai: Maharashtra Rajya Sahilya Sanskruti Mandal, Matralaya. p. 245.

10. Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 76–77. ISBN 978-1850654490.

11. Khairmode, Changdev Bhawanrao (1985). Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (Vol. 7) (in Marathi). Mumbai: Maharashtra Rajya Sahilya Sanskruti Mandal, Matralaya. p. 273.

12. "13A. Dr. Ambedkar in the Bombay Legislature PART I". Archivedfrom the original on 2 March 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

13. Kumar, Raj (9 August 2008). "Ambedkar and His Writings: A Look for the New Generation". Gyan Publishing House – via Google Books.

14.

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/prit ... 1920s.html Archived 17 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine>

15. https://thewire.in/culture/ambedkar-national-memorial-delhi-informal-guide

16. http://daic.gov.in/

17. "Archives released by LSE reveal BR Ambedkar's time as a scholar". 9 February 2016. Archived from the original on 9 February 2016.

18. Buswell, Robert Jr; Lopez, Donald S. Jr., eds. (2013). Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 34. ISBN 9780691157863.

19. Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). Ambedkar and Untouchability: Fighting the Indian Caste System. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-231-13602-1.

20. Pritchett, Frances. "In the 1890s" (PHP). Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

21. "Mahar". Encyclopædia Britannica. britannica.com. Archived from the original on 30 November 2011. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

22. Ahuja, M. L. (2007). "Babasaheb Ambedkar". Eminent Indians : administrators and political thinkers. New Delhi: Rupa. pp. 1922–1923. ISBN 978-8129111074. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

23. Ambedkar, B. R. "Waiting for a Visa". Frances Pritchett, translator. Columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

24. Kurian, Sangeeth. "Human rights education in schools". The Hindu.

25. "आंबडवे नाव योग्यच – खासदार अमर साबळे". 14 April 2016.

26. "डॉ. बाबासाहेब आंबेडकर यांचे मूळ गाव आंबवडे येथे आंतरराष्ट्रीय दर्जाचे शैक्षणिक संकुल". 18 April 2014.

27. "आंबेडकर गुरुजींचं कुटुंब जपतंय सामाजिक वसा, कुटुंबानं सांभाळल्या 'त्या' आठवणी".

28. "Bhim, Eklavya". outlookindia.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

29. S. N. Mishra (2010). Socio-economic and Political Vision of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. Concept Publishing Company. p. 96. ISBN 978-8180696749.

30. "ऐसे हुआ डॉ आंबेडकर का नाम परिवर्तन... तकनीक से सशक्तीकरण का सपना होगा साकार". NDTV. 14 April 2017.

31. Pritchett, Frances. "In the 1900s" (PHP). Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

32. Pritchett, Frances. "In the 1890s" (PHP). Archived from the original on 7 September 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

33. Pritchett, Frances. "In the 1910s" (PHP). Archived from the original on 23 November 2011. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

34. "Ambedkar teacher". 31 March 2016. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016.

35. "Bhimrao Ambedkar". columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 10 February 2014.

36. "Rescuing Ambedkar from pure Dalitism: He would've been India's best Prime Minister". Archived from the original on 6 November 2015.

37. Kshīrasāgara, Rāmacandra (1 January 1994). Dalit Movement in India and Its Leaders, 1857-1956. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788185880433. Retrieved 2 November 2016 – via Google Books.

38. Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture, Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780195169478

39. Bryant, Edwin. The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. pp. 50.

40. Sharma, Arvind (2005), "Dr. B. R. Ambedkar on the Aryan Invasion and the Emergence of the Caste System in India", J Am Acad Relig (September 2005) 73 (3): 849.

41. Sharma, Arvind (2005), "Dr. B. R. Ambedkar on the Aryan Invasion and the Emergence of the Caste System in India", J Am Acad Relig (September 2005) 73 (3): 851.

42. Sharma, Arvind (2005), "Dr. B. R. Ambedkar on the Aryan Invasion and the Emergence of the Caste System in India", J Am Acad Relig (September 2005) 73 (3): 854-5, 863.

43. Ambedkar, Dr. B.R. "Waiting for a Visa". columbia.edu. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 24 June 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

44. Keer, Dhananjay (1971) [1954]. Dr. Ambedkar: Life and Mission. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. pp. 37–38. ISBN 8171542379. OCLC 123913369.

45. Harris, Ian, ed. (22 August 2001). Buddhism and politics in twentieth-century Asia. Continuum International Group. ISBN 9780826451781.

46. Tejani, Shabnum (2008). "From Untouchable to Hindu Gandhi, Ambedkar and Depressed class question 1932". Indian secularism : a social and intellectual history, 1890-1950. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. pp. 205–210. ISBN 978-0253220448. Retrieved 17 July2013.

47. Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 4. ISBN 1850654492.

48. "Dr. Ambedkar". National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights. Archived from the original on 8 October 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

49. Benjamin, Joseph (June 2009). "B. R. Ambedkar: An Indefatigable Defender of Human Rights". Focus. Japan: Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center (HURIGHTS OSAKA). 56.

50. Thorat, Sukhadeo; Kumar, Narender (2008). B. R. Ambedkar:perspectives on social exclusion and inclusive policies. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

51. Ambedkar, B. R. (1979). Writings and Speeches. 1. Education Dept., Govt. of Maharashtra.

52. "Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar". Maharashtra Navanirman Sena. Archived from the original on 10 May 2011. Retrieved 26 December2010.

53. Kumar, Aishwary. "The Lies Of Manu". outlookindia.com. Archivedfrom the original on 18 October 2015.

54. "Annihilating caste". frontline.in. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014.

55. Menon, Nivedita (25 December 2014). "Meanwhile, for Dalits and Ambedkarites in India, December 25th is Manusmriti Dahan Din, the day on which B R Ambedkar publicly and ceremoniously in 1927". Kafila. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

56. "11. Manusmriti Dahan Day celebrated as Indian Women's Liberation Day" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 November 2015.

57. Keer, Dhananjay (1990). Dr. Ambedkar : life and mission (3rd ed.). Bombay: Popular Prakashan Private Limited. pp. 136–140. ISBN 8171542379.

58. "Poona Pact - 1932". Britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

59. "Ambekar vs Gandhi: A Part That Parted". Outlook. 20 August 2012. Archived from the original on 27 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

60. "Museum to showcase Poona Pact". The Times of India. 25 September 2007. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015. Read 8th Paragraph

61. Omvedt, Gail (2012). "A Part That Parted". Outlook India. The Outlook Group. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

62. Sharma; Sharma, B. K. (August 2007). Introduction to the Constitution of India. ISBN 9788120332461. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

63. "Gandhi's Epic Fast". Archived from the original on 12 November 2011.

64. Ravinder Kumar, "Gandhi, Ambedkar and the Poona pact, 1932." South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 8.1-2 (1985): 87-101.

65. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

66. Pritchett, Frances. "In the 1930s" (PHP). Archived from the original on 6 September 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

67. Jaffrelot, Christophe (2005). Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste. London: C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 76–77. ISBN 1850654492.

68. "May 15: It was 79 years ago today that Ambedkar's 'Annihilation Of Caste' was published". Archived from the original on 29 May 2016.

69. Mungekar, Bhalchandra (16–29 July 2011). "Annihilating caste". Frontline. 28 (11). Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2013.

70. Deb, Siddhartha, "Arundhati Roy, the Not-So-Reluctant Renegade"Archived 6 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times Magazine, 5 March 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

71. "A for Ambedkar: As Gujarat's freedom march nears tryst, an assertive Dalit culture spreads". Archived from the original on 16 September 2016.

72. Sialkoti, Zulfiqar Ali (2014), "An Analytical Study of the Punjab Boundary Line Issue during the Last Two Decades of the British Raj until the Declaration of 3 June 1947" (PDF), Pakistan Journal of History and Culture, XXXV (2), p. 73–76

73. Dhulipala, Venkat (2015), Creating a New Medina, Cambridge University Press, pp. 124, 134, 142–144, 149, ISBN 978-1-107-05212-3

74. Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji (1946). "Chapter X: Social Stagnation". Pakistan or the Partition of India. Bombay: Thackers Publishers. pp. 215–219. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

75. "Some Facts of Constituent Assembly". Parliament of India. National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011. On 29 August 1947, the Constituent Assembly set up an Drafting Committee under the Chairmanship of B. R. Ambedkar to prepare a Draft Constitution for India

76. Austin, Granville (1999), The Indian Constitution: Cornerstone of a Nation, Oxford University Press

77. Sheth, D. L. (November 1987). "Reservations Policy Revisited". Economic and Political Weekly. 22 (46): 1957–1962. JSTOR 4377730.

78. "Constitution of India". Ministry of Law and Justice of India. Archived from the original on 22 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October2013.

79. Sehgal, Narender (1994). "Chapter 26: Article 370". Converted Kashmir: Memorial of Mistakes. Delhi: Utpal Publications. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

80. Tilak. "Why Ambedkar refused to draft Article 370". Indymedia India. Archived from the original on 7 February 2004. Retrieved 17 September 2013.

81. "Ambedkar with UCC". Outlook India. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

82. "Ambedkar And The Uniform Civil Code". Archived from the original on 14 April 2016.

83. Pathak, Vikas (December 2015). "Ambedkar favoured common civil code". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016.

84. Chandrababu, B. S; Thilagavathi, L (2009). Woman, Her History and Her Struggle for Emancipation. Chennai: Bharathi Puthakalayam. pp. 297–298. ISBN 978-8189909970.

85. Dalmia, Vasudha; Sadana, Rashmi, eds. (2012). "The Politics of Caste Identity". The Cambridge Companion to Modern Indian Culture. Cambridge Companions to Culture (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0521516259.

86. Guha, Ramachandra (2008). India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-06-095858-9.

87. "Statistical Report On General Elections, 1951 to The First Lok Sabha: List of Successful Candidates" (PDF). Election Commission of India. pp. 83, 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014.

88. Sabha, Rajya. "Alphabetical List of All Members of Rajya Sabha Since 1952". Rajya Sabha Secretariat. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Serial Number 69 in the list

89. IEA. "Dr. B.R. Ambedkar's Economic and Social Thoughts and Their Contemporary Relevance" (PDF). IEA Newsletter – The Indian Economic Association(IEA). India: IEA publications. p. 10. Archived(PDF) from the original on 16 October 2013.

90. Mishra, S.N., ed. (2010). Socio-economic and political vision of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company. pp. 173–174. ISBN 978-8180696749.

91. TNN (15 October 2013). "Ambedkar had a vision for food self-sufficiency". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

92. Zelliot, Eleanor (1991). "Dr. Ambedkar and America". A talk at the Columbia University Ambedkar Centenary. Archived from the original on 3 November 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

93. Ingle, M R (September 2010). "Relevance of Dr. Ambedkar's Economic Philosophy in the Current Scenario" (PDF). International Research Journal. I (12). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

94. "अभिगमन तिथि" (PDF). Retrieved 28 November 2012.[dead link]

95. "B.R. Ambedkar and his philosophy of Land Reform: An evaluation"(PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

96. "Dr. B. R. AMBEDKAR" (PDF). Archived from the original(PDF) on 28 February 2013. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

97. "Round Table India - The Problem of the Rupee: Its Origin and Its Solution (History of Indian Currency & Banking)". Round Table India. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013.

98. "Ambedkar Lecture Series to Explore Influences on Indian Society". columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 21 December 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

99. Keer, Dhananjay (2005) [1954]. Dr. Ambedkar: life and mission. Mumbai: Popular Prakashan. pp. 403–404. ISBN 81-7154-237-9. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

100. Pritchett, Frances. "In the 1940s". Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

101. "Ambedkar's wife passes away". Archived from the original on 10 December 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

102. Cohen, Stephen P. (May 1969). "The Untouchable Soldier: Caste, Politics, and the Indian Army". The Journal of Asian Studies. 28 (3): 460. doi:10.2307/2943173. JSTOR 2943173. (subscription required)

103. Sangharakshita (2006). "Milestone on the Road to conversion". Ambedkar and Buddhism (1st South Asian ed.). New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. p. 72. ISBN 8120830237. Retrieved 17 July2013.

104. Pritchett, Frances. "In the 1950s" (PHP). Archived from the original on 20 June 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

105. Ganguly, Debjani; Docker, John, eds. (2007). Rethinking Gandhi and Nonviolent Relationality: Global Perspectives. Routledge studies in the modern history of Asia. 46. London: Routledge. p. 257. ISBN 978-0415437400. OCLC 123912708.

106. Quack, Johannes (2011). Disenchanting India: Organized Rationalism and Criticism of Religion in India. Oxford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0199812608. OCLC 704120510.

107. Online edition of Sunday Observer – Features Archived 3 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Sundayobserver.lk. Retrieved on 12 August 2012.

108. Sinha, Arunav. "Monk who witnessed Ambedkar's conversion to Buddhism". Archived from the original on 17 April 2015.

109. Sangharakshita (2006) [1986]. "After Ambedkar". Ambedkar and Buddhism (First South Asian ed.). New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 162–163. ISBN 81-208-3023-7.

110. Smith, Bardwell L., ed. (1976). Religion and social conflict in South Asia. Leiden: Brill. p. 16. ISBN 9004045104.

111. Kantowsky, Detlef (2003). Buddhists in India today:descriptions, pictures, and documents. Manohar Publishers & Distributors.

112. "President, PM condole Savita Ambedkar's death". The Hindu. 30 May 2003. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012.

113. Kshīrasāgara, Rāmacandra (1994). Dalit movement in India and its leaders, 1857–1956. New Delhi: M D Publications pvt Ltd. ISBN 9788185880433.

114. "maharashtrapoliticalparties". Archived from the original on 18 August 2012.

115. "Biographical Sketch, Member of Parliament, 13th Lok Sabha". parliamentofindia.nic.in. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011.

116. "Baba Saheb". Archived from the original on 5 May 2006.

117. "Homage to Dr Ambedkar: When all roads led to Chaityabhoomi". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012.

118. Ganguly, Debanji (2005). "Buddha, bhakti and 'superstition': a post-secular reading of dalit conversion". Caste, Colonialism and Counter-Modernity: : notes on a postcolonial hermeneutics of caste. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 172–173. ISBN 0-415-34294-5.

119. Joshi, Barbara R. (1986). Untouchable!: Voices of the Dalit Liberation Movement. Zed Books. pp. 11–14. ISBN 9780862324605. Archivedfrom the original on 29 July 2016.

120. Keer, D. (1990). Dr. Ambedkar: Life and Mission. Popular Prakashan. p. 61. ISBN 9788171542376. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016.

121. Bayly, Susan (2001). Caste, Society and Politics in India from the Eighteenth Century to the Modern Age. Cambridge University Press. p. 259. ISBN 9780521798426. Archived from the original on 1 August 2016.

122. Naik, C.D (2003). "Buddhist Developments in East and West Since 1950: An Outline of World Buddhism and Ambedkarism Today in Nutshell". Thoughts and philosophy of Doctor B.R. Ambedkar (First ed.). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. p. 12. ISBN 81-7625-418-5. OCLC 53950941.

123. "PM inaugurates Ambedkar memorial in London". The Hindy. 22 January 2018. Archived from the original on 17 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

124. "The Greatest Indian after Independence: BR Ambedkar". IBNlive. 15 August 2012. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012.

125. Planning Commission. "Member's Profile : Dr. Narendra Jadhav". Government of India. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

126. Pisharoty, Sangeeta Barooah (26 May 2013). "Words that were". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

127. Face the People - FTP: Nobel laureate Amartya Sen on economic growth, Indian politics. YouTube. 22 July 2013. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016.

128. "Ambedkar my father in Economics: Dr Amartya Sen « Atrocity News". atrocitynews.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012.

129. Menski, W. F. "The role of the judiciary in plural societies". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. Cambridge University. 52 (1): 172–174. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00023600.

130. Omvedt, Gail (1994). Dalits and the Democratic Revolution: Dr Ambedkar and the Dalit Movement in Colonial India. SAGE publications. p. 185. ISBN 9788132119838.

131. "One lakh people convert to Buddhism". The Hindu. 28 May 2007. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010.

132. Michael (1999), p. 65, notes that "The concept of Ambedkar as a Bodhisattva or enlightened being who brings liberation to all backward classes is widespread among Buddhists." He also notes how Ambedkar's pictures are enshrined side-to-side in Buddhist Vihars and households in India|office = Labour Member in Viceroy's Executive Counciln Buddhist homes.

133. "Magazine / Land & People: Ambedkar in Hungary". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 22 November 2009. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

134. "Resurgence of an icon Babasaheb Ambedkar".

135. Viswanathan, S (24 May 2010). "Ambedkar film: better late than never". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011.

136. Blundell, David (2006). "Arising Light: Making a Documentary Life History Motion Picture on Dr B. R. Ambedkar in India". Hsi Lai Journal of Humanistic Buddhism. 7. Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

137. Ramnara (5 March 2014). "Samvidhaan: The Making of the Constitution of India (TV Mini-Series 2014)". IMDb. Archived from the original on 27 May 2015.

138. Anima, P. (17 July 2009). "A spirited adventure". The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 2 January 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2009.

139. Calvi, Nuala (23 May 2011). "The top five political comic books". CNN. Archived from the original on 9 January 2013. Retrieved 14 April2013.

140. "Dr. B.R. Ambedkar Samajik Parivartan Sthal". Department of Tourism, Government of UP, Uttar Pradesh. Archived from the originalon 19 July 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013. New Attractions

141. "Ambedkar Memorial, Lucknow/India" (PDF). Remmers India Pvt. Ltd. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 17 July 2013. Brief Description

142. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

143. Gibbs, Jonathan (14 April 2015). "B. R. Ambedkar's 124th Birthday: Indian social reformer and politician honoured with a Google Doodle". The Independent. Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

144. "B R Ambedkar 124th birth anniversary: Google doodle changes in 7 countries as tribute". The Indian Express. 14 April 2015. Archivedfrom the original on 7 July 2015.

145. "Google's BR Ambedkar birth anniversary doodle on 7 other countries apart from India". dna. 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 7 July 2015.

146. Nelson, Dean (14 April 2015). "B.R. Ambedkar, a hero of India's independence movement, honoured by Google Doodle". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016.

147. "A new TV show on B.R.Ambedkar raises questions of responsible representation".

148. Ambedkar, B. R. (1979), Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, writings and speeches, Mumbai: Education Dept., Government of Maharashtra, OL 4080132M

Further reading· Ahir, D. C. (September 1990). The Legacy of Dr. Ambedkar. Delhi: B. R. Publishing. ISBN 81-7018-603-X.

· Ajnat, Surendra (1986). Ambedkar on Islam. Jalandhar: Buddhist Publ.

· Beltz, Johannes; Jondhale, S. (eds.). Reconstructing the World: B.R. Ambedkar and Buddhism in India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

· Bholay, Bhaskar Laxman (2001). Dr Dr. Baba Saheb Ambedkar: Anubhav Ani Athavani. Nagpur: Sahitya Akademi.

· Fernando, W. J. Basil (2000). Demoralisation and Hope: Creating the Social Foundation for Sustaining Democracy—A comparative study of N. F. S. Grundtvig (1783–1872) Denmark and B. R. Ambedkar (1881–1956) India. Hong Kong: AHRC Publication. ISBN 962-8314-08-4.

· Chakrabarty, Bidyut. "B.R. Ambedkar" Indian Historical Review (Dec 2016) 43#2 pp 289–315. doi:10.1177/0376983616663417.

· Gautam, C. (2000). Life of Babasaheb Ambedkar (Second ed.). London: Ambedkar Memorial Trust.

· Jaffrelot, Christophe (2004). Ambedkar and Untouchability. Analysing and Fighting Caste. New York: Columbia University Press.

· Kasare, M. L. Economic Philosophy of Dr. B.R. Ambedkar. New Delhi: B. I. Publications.

· Kuber, W. N. Dr. Ambedkar: A Critical Study. New Delhi: People's Publishing House.

· Kumar, Aishwary. Radical Equality: Ambedkar, Gandhi, and the Risk of Democracy (2015).

· Kumar, Ravinder. "Gandhi, Ambedkar and the Poona pact, 1932." South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 8.1-2 (1985): 87-101.

· Michael, S.M. (1999). Untouchable, Dalits in Modern India. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-55587-697-5.

· Nugent, Helen M. (1979) "The communal award: The process of decision-making." South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 2#1-2 (1979): 112-129.

· Omvedt, Gail (January 2004). Ambedkar: Towards an Enlightened India. ISBN 0-670-04991-3.

· Sangharakshita, Urgyen (1986). Ambedkar and Buddhism. ISBN 0-904766-28-4. PDF

Primary sources· Ambedkar, Bhimrao Ramji. Annihilation of caste: The annotated critical edition (Verso Books, 2014).