B. R. Ambedkar [Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar]

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/17/20

"Bhimrao Ambedkar" redirects here. For the Uttar Pradesh politician, see Bhimrao Ambedkar (Uttar Pradesh politician).

We must now turn to the evaluation of means. We must ask whose means are superior and lasting in the long run. There are, however some misunderstandings on both sides. It is necessary to clear them up. Take violence. As to violence, there are many people who seem to shiver at the very thought of it. But this is only a sentiment. Violence cannot be altogether dispensed with. Even in non-communist countries a murderer is hanged. Does not hanging amount to violence? Non-communist countries go to war with non-communist countries. Millions of people are killed. Is this no violence? If a murderer can be killed, because he has killed a citizen, if a soldier can be killed in war because he belongs to a hostile nation, why cannot a property owner be killed if his ownership leads to misery for the rest of humanity? There is no reason to make an exception in favour of the property owner, why one should regard private property as sacrosanct.

The Buddha was against violence. But he was also in favour of justice, and where justice required, he permitted the use of force...

"Does the Tathagata prohibit all war, even when it is in the interest of Truth and Justice?"

Buddha replied. You have wrongly understood what I have been preaching. An offender must be punished, and an innocent man must be freed. It is not a fault of the Magistrate if he punishes an offender. The cause of punishment is the fault of the offender. The Magistrate who inflicts the punishment is only carrying out the law. He does not become stained with Ahimsa. A man who fights for justice and safety cannot be accused of Ahimsa. If all the means of maintaining peace have failed, then the responsibility for Himsa falls on him who starts war. One must never surrender to evil powers. War there may be. But it must not be for selfish ends...."

There are of course other grounds against violence such as those urged by Prof. John Dewey. In dealing with those who contend that the end justifies the means is [a] morally perverted doctrine, Dewey has rightly asked what can justify the means if not the end? It is only the end that can justify the means.

Buddha would have probably admitted that it is only the end which would justify the means. What else could? And he would have said that if the end justified violence, violence was a legitimate means for the end in view. He certainly would not have exempted property owners from force if force were the only means for that end. As we shall see, his means for the end were different. As Prof. Dewey has pointed out that violence is only another name for the use of force and although force must be used for creative purposes a distinction between use of force as energy and use of force as violence needs to be made. The achievement of an end involves the destruction of many other ends, which are integral with the one that is sought to be destroyed. Use of force must be so regulated that it should save as many ends as possible in destroying the evil one. Buddha's Ahimsa was not as absolute as the Ahimsa preached by Mahavira the founder of Jainism. He would have allowed force only as energy. The communists preach Ahimsa as an absolute principle. To this the Buddha was deadly opposed...

As to Dictatorship, the Buddha would have none of it. He was born a democrat, and he died a democrat...

The Bhikshu Sangh had the most democratic constitution. He was only one of the Bhikkus. At the most he was like a Prime Minister among members of the Cabinet. He was never a dictator...

The Communists themselves admit that their theory of the State as a permanent dictatorship is a weakness in their political philosophy. They take shelter under the plea that the State will ultimately wither away. There are two questions, which they have to answer. When will it wither away? What will take the place of the State when it withers away? To the first question they can give no definite time. Dictatorship for a short period may be good, and a welcome thing even for making Democracy safe. Why should not Dictatorship liquidate itself after it has done its work, after it has removed all the obstacles and boulders in the way of democracy and has made the path of Democracy safe. Did not Asoka set an example? He practised violence against the Kalingas. But thereafter he renounced violence completely. If our victor’s to-day not only disarm their victims, but also disarm themselves, there would be peace all over the world...

The Communists have given no answer. At any rate no satisfactory answer to the question what would take the place of the State when it withers away, though this question is more important than the question when the State will wither away. Will it be succeeded by Anarchy? If so, the building up of the Communist State is an useless effort. If it cannot be sustained except by force, and if it results in anarchy when the force holding it together is withdrawn, what good is the Communist State? The only thing which could sustain it after force is withdrawn is Religion. But to the Communists Religion is anathema. Their hatred to Religion is so deep seated that they will not even discriminate between religions which are helpful to Communism and religions which are not. The Communists have carried their hatred of Christianity to Buddhism without waiting to examine the difference between the two. The charge against Christianity levelled by the Communists was two fold. Their first charge against Christianity was that they made people other worldliness and made them suffer poverty in this world. As can be seen from quotations from Buddhism in the earlier part of this tract, such a charge cannot be levelled against Buddhism.

The second charge levelled by the Communists against Christianity cannot be levelled against Buddhism. This charge is summed up in the statement that Religion is the opium of the people. This charge is based upon the Sermon on the Mount which is to be found in the Bible. The Sermon on the Mount sublimates poverty and weakness. It promises heaven to the poor and the weak. There is no Sermon on the Mount to be found in the Buddha's teachings. His teaching is to acquire wealth. I give below his Sermon on the subject to Anathapindika one of his disciples.

Once Anathapindika came to where the Exalted One was staying. Having come, he made obeisance to the Exalted One, and took a seat at one side, and asked, "Will the Enlightened One tell what things are welcome, pleasant, agreeable, to the householder but which are hard to gain."

The Enlightened One having heard the question put to him said "Of such things the first is to acquire wealth lawfully."

"The second is to see that your relations also get their wealth lawfully."

"The third is to live long and reach great age."...

"Thus to acquire wealth legitimately and justly, earn by great industry, amassed by strength of the arm and gained by sweat of the brow is a great blessing. The householder makes himself happy and cheerful and preserves himself full of happiness; also makes his parents, wife, and children, servants, and labourers, friends and companions happy and cheerful, and preserves them full of happiness."...

The Russians are proud of their Communism. But they forget that the wonder of all wonders is that the Buddha established Communism so far as the Sangh was concerned without dictatorship. It may be that it was a communism on a very small scale, but it was communism without dictatorship, a miracle which Lenin failed to do...

It has been claimed that the Communist Dictatorship in Russia has wonderful achievements to its credit. There can be no denial of it. That is why I say that a Russian Dictatorship would be good for all backward countries. But this is no argument for permanent Dictatorship. Humanity does not only want economic values, it also wants spiritual values to be retained. Permanent Dictatorship has paid no attention to spiritual values, and does not seem to intend to. Carlyle called Political Economy a Pig Philosophy. Carlyle was of course wrong. For man needs material comforts. But the Communist Philosophy seems to be equally wrong, for the aim of their philosophy seems to be fatten pigs as though men are no better than pigs. Man must grow materially as well as spiritually. Society has been aiming to lay a new foundation was summarised by the French Revolution in three words: Fraternity, Liberty and Equality. The French Revolution was welcomed because of this slogan. It failed to produce equality. We welcome the Russian Revolution because it aims to produce equality. But it cannot be too much emphasised that in producing equality, society cannot afford to sacrifice fraternity or liberty. Equality will be of no value without fraternity or liberty. It seems that the three can coexist only if one follows the way of the Buddha. Communism can give one but not all.

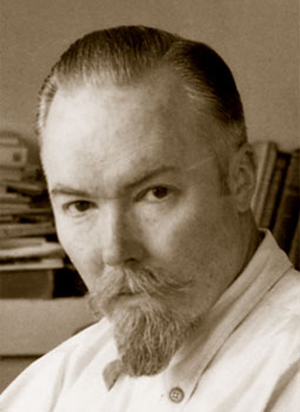

-- B. R. Ambedkar, Excerpt from "A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West", by Donald S. Lopez, Jr.

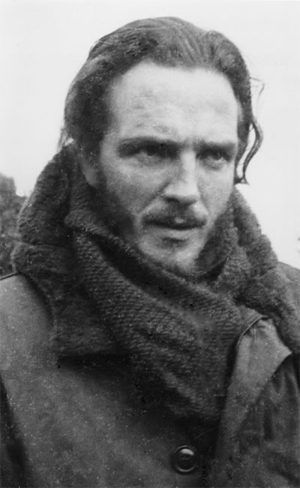

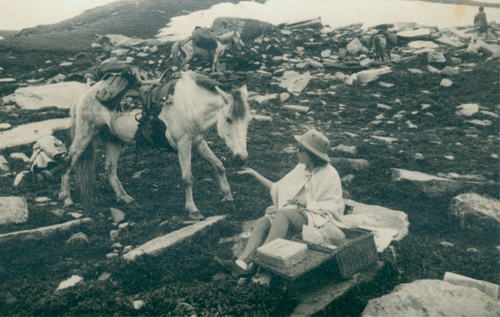

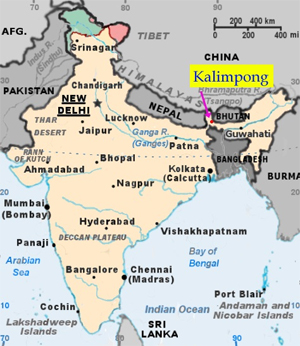

I stayed in Kalimpong for the next fourteen years, working for the good of Buddhism as best I could, getting to know the local people, both Buddhist and Hindu, and being uplifted and inspired by the sight of Mount Kanchenjunga, the third highest peak in the world, dazzlingly white against the blue sky. In the course of my first seven years in the town I founded a Young Men’s Buddhist Association; started a monthly journal of Himalayan religion, culture, and education called Stepping-Stones; was ordained as a bhikshu or full monk by an international sangha; organized a public reception for the relics of the Buddha’s two chief disciples, then touring India amid scenes of wild popular enthusiasm, found a kindred spirit in Lama Govinda, the German-born artist and scholar; re-established contact with the Maha Bodhi Society (conditions at its headquarters had recently changed for the better); and became well known as a lecturer not only in Kalimpong and the surrounding area but also in Calcutta, Bombay, and Bangalore.

But if I was not to work for the good of Buddhismat the expense of my own good, spiritually speaking, I needed to have a means of uniting the two. I found this in the Bodhisattva ideal, especially as presented in Šãntideva’s Šikëã-samuccaya or Collection of Teachings: the ideal of the one who strives for Enlightenment not just for his own sake but for the sake of all living beings. It was not that the Bodhisattva literally gave up the prospect of Nirvãna for himself in order to remain in the world and help others achieve Nirvãna, as in the popular version of the ideal, but rather that he saw no difference between striving for his own Enlightenment and striving for theirs. He saw no difference because he had transcended the dichotomy of ‘self’ and ‘others’; and it was this very dichotomy that was the real obstacle to Enlightenment. Some years later I affirmed my allegiance to the Bodhisattva ideal by taking the Bodhisattva ordination. I took it from Dhardo Rimpoche, a Tibetan incarnate lama who had arrived in Kalimpong shortly before I did, whom I gradually got to know, and whom I came to revere as a living embodiment of the Bodhisattva ideal.

During those first seven years in Kalimpong I operated from a succession of borrowed or rented premises. In March 1957 the generosity of friends enabled me to buy a small hillside property on the outskirts of the town and there establish the Triyana Vardhana Vihara, the Monastery Where the Three Yanas Flourish. It was the year of the Buddha Jayanti or 2,500th anniversary of Buddhism, a year that was important for me on a number of counts. Besides establishing the Triyana Vardhana Vihara, I toured the Buddhist holy places as a guest of the Government of India together with Dhardo Rimpoche and fifty-odd other ‘Eminent Buddhists from the Border Areas’; took part in the official Buddha Jayanti celebrations in Delhi; met the Dalai and Panchen Lamas; and had the satisfaction of seeing my book A Survey of Buddhism published to widespread acclaim. Most important of all, perhaps, I became involved with the movement of mass conversion of so-called ‘ex-Untouchable’ Hindus to Buddhism.

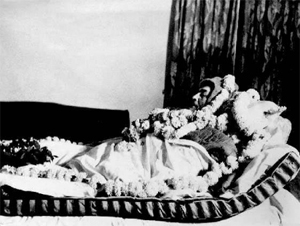

This historic movement had begun in Nagpur, where Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the leader of the ex-Untouchables, had embraced Buddhism with 400,000 of his followers. Six weeks later he died suddenly in Delhi. I happened to arrive in Nagpur less than an hour before the news of his death was received there, and that night I addressed a condolence meeting attended by 100,000 grief-stricken and demoralized new Buddhists.

Ambedkar was not dead, I assured my audience. He lived on in them, and his work –- especially the work of conversion -– had to continue. In the next four days I visited practically all the ex-Untouchable ghettoes in the city, made more than forty speeches, and initiated 30,000 persons into Buddhism. By the time I left for Calcutta I had addressed altogether 200,000 people, and given them renewed confidence in their future as Buddhists. Leading members of the community declared that I had saved Nagpur for Buddhism. That may or may not have been true. I had certainly forged with the Buddhists of Nagpur, and indeed with all Ambedkar’s followers, a link that was destined to endure.

In the course of my second seven years in Kalimpong I developed the Triyana Vardhana Vihara as a centre of interdenominational Buddhism. Thai, Vietnamese, and Tibetan monks came to stay with me, and there was even the occasional Western Buddhist. Much of my time when I was actually in Kalimpong was spent at my desk, and my literary output during this period included the books later published as The Three Jewels and The Eternal Legacy. At the suggestion of a friend I also started writing my memoirs. When not in Kalimpong I was usually to be found either in Calcutta, editing the Maha Bodhi Society’s monthly journal, or touring central and western India preaching to the followers of Dr Ambedkar. The fourth and longest of my preaching tours lasted from October 1961 to May 1962. In those eight months I visited more than half the states of India, gave nearly 200 lectures, and received 25,000 men and women into the Buddhist community.

But there was another thread running through the fabric of my life, during that second seven-year period: the colourful thread of the Vajrayãna. Since the invasion of Tibet by the Chinese in 1950, there had been a steady trickle of refugees into Kalimpong, and in 1959, when the Dalai Lama himself fled to India, the trickle became a flood. A number of the refugees were incarnate lamas. Naturally I got to know these, and between 1957 and 1964 received from some of the most distinguished of them various Vajrayãna initiations. Among my Vajrayãna gurus were Dilgo Khyentse Rimpoche and Dudjom Rimpoche, both of whom subsequently became well known in the West. The Vajrayãna being nothing if not practical, I naturally came to devote more and more of the time I spent in Kalimpong to deity yoga and to the Four Foundation Yogas, especially to the Going for Refuge and Prostration Practice centred upon the figure of Padmasambhava, to whom I had felt strongly drawn ever since my arrival in the Himalayan region. As though in recognition of my connection with him, in the course of one of my initiations I was given the name Urgyen, Padmasambhava being known as the Guru from Urgyen or Uddiyãna.

In 1963 the English Sangha Trust invited me to spend a few months in England. Prior to that I had not thought even of visiting the West: my life and my work lay in India. Two considerations induced me, eventually, to accept the invitation. The first was that my presence might help resolve the differences that had arisen between the two principal Buddhist organizations in London; the second, that my parents were growing old and I ought to see them. After several delays and postponements, and one more visit to western India, in August 1964 I therefore returned to England after an absence of twenty years.

-- Moving Against the Stream: The Birth of a new Buddhist Movement, by Sangharakshita [Dennis Lingwood]

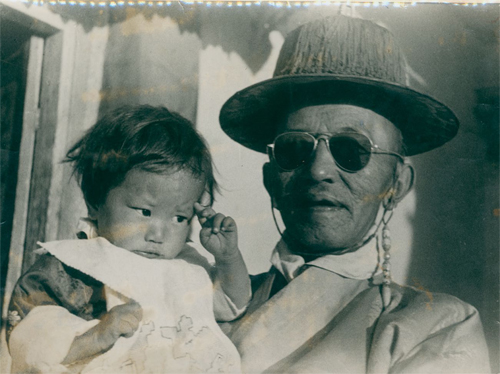

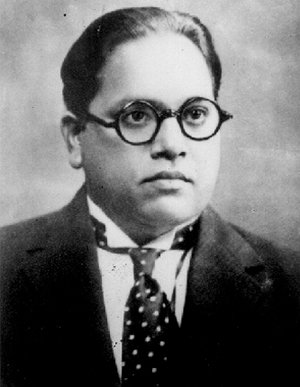

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar as a young man

Member of Parliament of Rajya Sabha for Bombay State[1]

In office: 3 April 1952 – 6 December 1956

President: Rajendra Prasad

Prime Minister: Jawaharlal Nehru

1st Minister of Law and Justice

In office: 15 August 1947 – 6 October 1951

President: Rajendra Prasad

Governor General: Louis Mountbatten; C. Rajagopalachari

Prime Minister: Jawaharlal Nehru

Preceded by: Position established

Succeeded by: Charu Chandra Biswas

Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee

In office: 29 August 1947 – 24 January 1950

Member of the Constituent Assembly of India[2][3]

In office: 9 December 1946 – 24 January 1950

Constituency: Bengal Province (1946-47); Bombay Province (1947-50)

Labour Member, Viceroy's Executive Council[4][5][6]

In office: 22 July 1942 – 20 October 1946

Governor General: The Marquess of Linlithgow; The Viscount Wavell

Preceded by: Feroz Khan Noon

Leader of the Opposition in the Bombay Legislative Assembly[7][8]

In office: 1937–1942

Member of the Bombay Legislative Assembly[9][10]

In office: 1937–1942

Constituency: Bombay City (Byculla and Parel) General Urban

Member of the Bombay Legislative Council[11][12][13][14]

In office: 1926–1937

Personal details

Pronunciation: Bhīmrāo Rāmjī Āmbēḍkar

Born: Bhiva Ramji Sakpal, 14 April 1891, Mhow, Central Provinces, British India (present-day Bhim Janmabhoomi, Dr. Ambedkar Nagar, Indore district, Madhya Pradesh, India)

Died: 6 December 1956 (aged 65); Dr. Ambedkar National Memorial[15][16] (Dr. Ambedkar Parinirvan Bhoomi), Delhi, New Delhi, India

Resting place: Chaitya Bhoomi, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Political party: Independent Labour Party; Scheduled Castes Federation

Other political affiliations: Republican Party of India

Spouse(s): Ramabai Ambedkar (m. 1906; died 1935); Savita Ambedkar (m. 1948)

Children: Yashwant Ambedkar

Mother: Bhimabai Ramji Sakpal

Father: Ramji Maloji Sakpal

Relatives: See Ambedkar family

Residence: Rajgruha, Mumbai, Maharashtra; 26 Alipur road, Dr. Ambedkar National Memorial, New Delhi

Alma mater: University of Mumbai (B.A., M.A.); Columbia University (M.A., PhD); London School of Economics (M.Sc., D.Sc.); Gray's Inn (Barrister-at-Law)

Profession: Jurist economist academic politician social reformer anthropologist writer

Known for: Dalit rights movement; Drafting Constitution of India; Dalit Buddhist movement

Awards: Bharat Ratna (posthumously in 1990)

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (14 April 1891 – 6 December 1956), also known as Babasaheb Ambedkar, was an Indian jurist, economist, politician and social reformer, who inspired the Dalit Buddhist movement and campaigned against social discrimination towards the untouchables (Dalits). He was independent India's first Minister of Law and Justice, and the chief architect of the Constitution of India.

Ambedkar was a prolific student, earning doctorates in economics from both Columbia University and the London School of Economics, and gaining reputation as a scholar for his research in law, economics and political science.[17] In his early career, he was an economist, professor, and lawyer. His later life was marked by his political activities; he became involved in campaigning and negotiations for India's independence, publishing journals, advocating political rights and social freedom for Dalits, and contributing significantly to the establishment of the state of India. In 1956, he converted to Buddhism, initiating mass conversions of Dalits.[18]

In 1990, the Bharat Ratna, India's highest civilian award, was posthumously conferred upon Ambedkar. Ambedkar's legacy includes numerous memorials and depictions in popular culture.

Early life

Ambedkar was born on 14 April 1891 in the town and military cantonment of Mhow in the Central Provinces (now in Madhya Pradesh).[19] He was the 14th and last child of Ramji Maloji Sakpal, an army officer who held the rank of Subedar, and Bhimabai Sakpal, daughter of Laxman Murbadkar.[20] His family was of Marathi background from the town of Ambadawe (Mandangad taluka) in Ratnagiri district of modern-day Maharashtra. Ambedkar was born into a poor low Mahar (dalit) caste, who were treated as untouchables and subjected to socio-economic discrimination.[21] Ambedkar's ancestors had long worked for the army of the British East India Company, and his father served in the British Indian Army at the Mhow cantonment.[22] Although they attended school, Ambedkar and other untouchable children were segregated and given little attention or help by teachers. They were not allowed to sit inside the class. When they needed to drink water, someone from a higher caste had to pour that water from a height as they were not allowed to touch either the water or the vessel that contained it. This task was usually performed for the young Ambedkar by the school peon, and if the peon was not available then he had to go without water; he described the situation later in his writings as "No peon, No Water".[23] He was required to sit on a gunny sack which he had to take home with him.[24]

Ramji Sakpal retired in 1894 and the family moved to Satara two years later. Shortly after their move, Ambedkar's mother died. The children were cared for by their paternal aunt and lived in difficult circumstances. Three sons – Balaram, Anandrao and Bhimrao – and two daughters – Manjula and Tulasa – of the Ambedkars survived them. Of his brothers and sisters, only Ambedkar passed his examinations and went to high school. His original surname was Sakpal but his father registered his name as Ambadawekar in school, meaning he comes from his native village 'Ambadawe' in Ratnagiri district.[25][25][26][27][28] His Deshastha Brahmin teacher, Krishna Mahadev Ambedkar, changed his surname from 'Ambadawekar' to his own surname 'Ambedkar' in school records.[29][30]

Education

Post-secondary education

In 1897, Ambedkar's family moved to Mumbai where Ambedkar became the only untouchable enrolled at Elphinstone High School. In 1906, when he was about 15 years old, his marriage to a nine-year-old girl, Ramabai, was arranged.[31]

Undergraduate studies at the University of Bombay

Ambedkar as a student

In 1907, he passed his matriculation examination and in the following year he entered Elphinstone College, which was affiliated to the University of Bombay, becoming, according to him, the first from his Mahar caste to do so. When he passed his English fourth standard examinations, the people of his community wanted to celebrate because they considered that he had reached "great heights" which he says was "hardly an occasion compared to the state of education in other communities". A public ceremony was evoked, to celebrate his success, by the community, and it was at this occasion that he was presented with a biography of the Buddha by Dada Keluskar, the author and a family friend.[32]

By 1912, he obtained his degree in economics and political science from Bombay University, and prepared to take up employment with the Baroda state government. His wife had just moved his young family and started work when he had to quickly return to Mumbai to see his ailing father, who died on 2 February 1913.[33]

Postgraduate studies at Columbia University

In 1913, Ambedkar moved to the United States at the age of 22. He had been awarded a Baroda State Scholarship of £11.50 (Sterling) per month for three years under a scheme established by Sayajirao Gaekwad III (Gaekwad of Baroda) that was designed to provide opportunities for postgraduate education at Columbia University in New York City. Soon after arriving there he settled in rooms at Livingston Hall with Naval Bhathena, a Parsi who was to be a lifelong friend. He passed his M.A. exam in June 1915, majoring in Economics, and other subjects of Sociology, History, Philosophy and Anthropology. He presented a thesis, Ancient Indian Commerce. Ambedkar was influenced by John Dewey and his work on democracy.[34]

In 1916 he completed his second thesis, National Dividend of India - A Historic and Analytical Study, for another M.A.[35] On 9 May, he presented the paper Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development before a seminar conducted by the anthropologist Alexander Goldenweiser.

Postgraduate studies at the London School of Economics

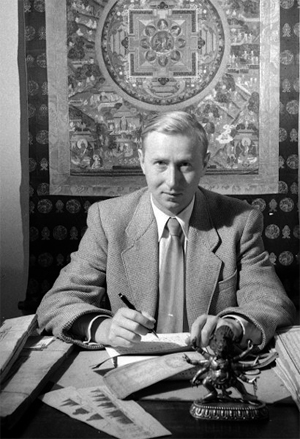

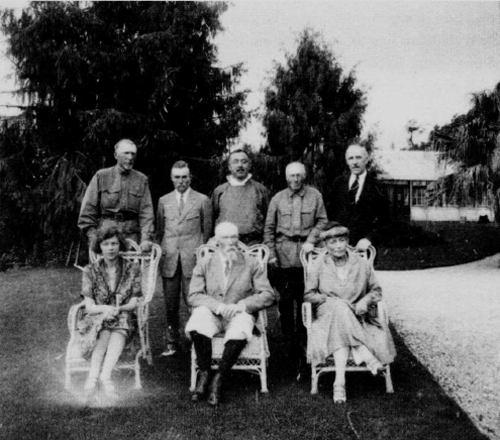

Ambedkar (In center line, first from right) with his professors and friends from the London School of Economics (1916-17)

In October 1916, he enrolled for the Bar course at Gray's Inn, and at the same time enrolled at the London School of Economics where he started working on a doctoral thesis. In June 1917, he returned to India because his scholarship from Baroda ended. His book collection was dispatched on different ship from the one he was on, and that ship was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine.[33] He got permission to return to London to submit his thesis within four years. He returned at the first opportunity, and completed a master's degree in 1921. His thesis was on "The problem of the rupee: Its origin and its solution".[36] In 1923, he completed a D.Sc. in Economics, and the same year he was called to the Bar by Gray's Inn. His third and fourth Doctorates (LL.D, Columbia, 1952 and D.Litt., Osmania, 1953) were conferred honoris causa.[37]

Opposition to Aryan invasion theory

Ambedkar viewed the Shudras as Aryan and adamantly rejected the Aryan invasion theory, describing it as "so absurd that it ought to have been dead long ago" in his 1946 book Who Were the Shudras?.[38]

Ambedkar viewed Shudras as originally being "part of the Kshatriya Varna in the Indo-Aryan society", but became socially degraded after they inflicted many tyrannies on Brahmins.[39]

According to Arvind Sharma, Ambedkar noticed certain flaws in the Aryan invasion theory that were later acknowledged by western scholarship. For example, scholars now acknowledge anās in Rig Veda 5.29.10 refers to speech rather than the shape of the nose.[40] Ambedkar anticipated this modern view by stating:

The term Anasa occurs in Rig Veda V.29.10. What does the word mean? There are two interpretations. One is by Prof. Max Muller. The other is by Sayanacharya. According to Prof. Max Muller, it means 'one without nose' or 'one with a flat nose' and has as such been relied upon as a piece of evidence in support of the view that the Aryans were a separate race from the Dasyus. Sayanacharya says that it means 'mouthless,' i.e., devoid of good speech. This difference of meaning is due to difference in the correct reading of the word Anasa. Sayanacharya reads it as an-asa while Prof. Max Muller reads it as a-nasa. As read by Prof. Max Muller, it means 'without nose.' Question is : which of the two readings is the correct one? There is no reason to hold that Sayana's reading is wrong. On the other hand there is everything to suggest that it is right. In the first place, it does not make non-sense of the word. Secondly, as there is no other place where the Dasyus are described as noseless, there is no reason why the word should be read in such a manner as to give it an altogether new sense. It is only fair to read it as a synonym of Mridhravak. There is therefore no evidence in support of the conclusion that the Dasyus belonged to a different race.[40]

Ambedkar disputed various hypotheses of the Aryan homeland being outside India, and concluded the Aryan homeland was India itself.[41] According to Ambedkar, the Rig Veda says Aryans, Dāsa and Dasyus were competing religious groups, not different peoples.[42]

Opposition to untouchability

Ambedkar as a barrister in 1922

As Ambedkar was educated by the Princely State of Baroda, he was bound to serve it. He was appointed Military Secretary to the Gaikwad but had to quit in a short time. He described the incident in his autobiography, Waiting for a Visa.[43] Thereafter, he tried to find ways to make a living for his growing family. He worked as a private tutor, as an accountant, and established an investment consulting business, but it failed when his clients learned that he was an untouchable.[44] In 1918, he became Professor of Political Economy in the Sydenham College of Commerce and Economics in Mumbai. Although he was successful with the students, other professors objected to his sharing a drinking-water jug with them.[45]

Ambedkar had been invited to testify before the Southborough Committee, which was preparing the Government of India Act 1919. At this hearing, Ambedkar argued for creating separate electorates and reservations for untouchables and other religious communities.[46] In 1920, he began the publication of the weekly Mooknayak (Leader of the Silent) in Mumbai with the help of Shahu of Kolhapur i.e. Shahu IV (1874–1922).[47]

Ambedkar went on to work as a legal professional. In 1926, he successfully defended three non-Brahmin leaders who had accused the Brahmin community of ruining India and were then subsequently sued for libel. Dhananjay Keer notes that "The victory was resounding, both socially and individually, for the clients and the doctor".

While practising law in the Bombay High Court, he tried to promote education to untouchables and uplift them. His first organised attempt was his establishment of the central institution Bahishkrit Hitakarini Sabha, intended to promote education and socio-economic improvement, as well as the welfare of "outcastes", at the time referred to as depressed classes.[48] For the defence of Dalit rights, he started many periodicals like Mook Nayak, Bahishkrit Bharat, and Equality Janta.[49]

He was appointed to the Bombay Presidency Committee to work with the all-European Simon Commission in 1925.[50] This commission had sparked great protests across India, and while its report was ignored by most Indians, Ambedkar himself wrote a separate set of recommendations for the future Constitution of India.[51]

By 1927, Ambedkar had decided to launch active movements against untouchability. He began with public movements and marches to open up public drinking water resources. He also began a struggle for the right to enter Hindu temples. He led a satyagraha in Mahad to fight for the right of the untouchable community to draw water from the main water tank of the town.[52] In a conference in late 1927, Ambedkar publicly condemned the classic Hindu text, the Manusmriti (Laws of Manu), for ideologically justifying caste discrimination and "untouchability", and he ceremonially burned copies of the ancient text. On 25 December 1927, he led thousands of followers to burn copies of Manusmrti.[53][54] Thus annually 25 December is celebrated as Manusmriti Dahan Din (Manusmriti Burning Day) by Ambedkarites and Dalits.[55][56]

In 1930, Ambedkar launched Kalaram Temple movement after three months of preparation. About 15,000 volunteers assembled at Kalaram Temple satygraha making one of the greatest processions of Nashik. The procession was headed by a military band, a batch of scouts, women and men walked in discipline, order and determination to see the god for the first time. When they reached to gate, the gates were closed by Brahmin authorities.[57]

Poona Pact

M.R. Jayakar, Tej Bahadur Sapru and Ambedkar at Yerwada jail, in Poona, on 24 September 1932, the day the Poona Pact was signed

In 1932, British announced the formation of a separate electorate for "Depressed Classes" in the Communal Award. Gandhi fiercely opposed a separate electorate for untouchables, saying he feared that such an arrangement would divide the Hindu community.[58][59][60] Gandhi protested by fasting while imprisoned in the Yerwada Central Jail of Poona. Following the fast, Congress politicians and activists such as Madan Mohan Malaviya and Palwankar Baloo organised joint meetings with Ambedkar and his supporters at Yerwada.[61] On 25 September 1932, the agreement known as Poona Pact was signed between Ambedkar (on behalf of the depressed classes among Hindus) and Madan Mohan Malaviya (on behalf of the other Hindus). The agreement gave reserved seats for the depressed classes in the Provisional legislatures, within the general electorate. Due to the pact, the depressed class received 148 seats in the legislature, instead of the 71 as allocated in the Communal Award earlier proposed by British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. The text uses the term "Depressed Classes" to denote Untouchables among Hindus who were later called Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes under India Act 1935, and the later Indian Constitution of 1950.[62][63] In the Poona Pact, a unified electorate was in principle formed, but primary and secondary elections allowed Untouchables in practice to choose their own candidates.[64]

Political career

Ambedkar with his family members at Rajgraha in February 1934. From left – Yashwant (son), Ambedkar, Ramabai (wife), Laxmibai (wife of his elder brother, Balaram), Mukund (nephew) and Ambedkar’s favourite dog, Tobby

In 1935, Ambedkar was appointed principal of the Government Law College, Bombay, a position he held for two years. He also served as the chairman of Governing body of Ramjas College, University of Delhi, after the death of its Founder Shri Rai Kedarnath.[65] Settling in Bombay (today called Mumbai), Ambedkar oversaw the construction of a house, and stocked his personal library with more than 50,000 books.[66] His wife Ramabai died after a long illness the same year. It had been her long-standing wish to go on a pilgrimage to Pandharpur, but Ambedkar had refused to let her go, telling her that he would create a new Pandharpur for her instead of Hinduism's Pandharpur which treated them as untouchables. At the Yeola Conversion Conference on 13 October in Nasik, Ambedkar announced his intention to convert to a different religion and exhorted his followers to leave Hinduism.[66] He would repeat his message at many public meetings across India.

In 1936, Ambedkar founded the Independent Labour Party, which contested the 1937 Bombay election to the Central Legislative Assembly for the 13 reserved and 4 general seats, and secured 11 and 3 seats respectively.[67]

Ambedkar published his book Annihilation of Caste on 15 May 1936.[68] It strongly criticised Hindu orthodox religious leaders and the caste system in general,[69] and included "a rebuke of Gandhi" on the subject.[70] Later, in a 1955 BBC interview, he accused Gandhi of writing in opposition of the caste system in English language papers while writing in support of it in Gujarati language papers.[71]

Ambedkar served on the Defence Advisory Committee[6] and the Viceroy's Executive Council as minister for labour.[6]

After the Lahore resolution (1940) of the Muslim League demanding Pakistan, Ambedkar wrote a 400 page tract titled Thoughts on Pakistan, which analysed the concept of "Pakistan" in all its aspects. Ambedkar argued that the Hindus should concede Pakistan to the Muslims. He proposed that the provincial boundaries of Punjab and Bengal should be redrawn to separate the Muslim and non-Muslim majority parts. He thought the Muslims could have no objection to redrawing provincial boundaries. If they did, they did not quite "understand the nature of their own demand". Scholar Venkat Dhulipala states that Thoughts on Pakistan "rocked Indian politics for a decade". It determined the course of dialogue between the Muslim League and the Indian Naitonal Congress, paving the way for the Partition of India.[72][73]

In his work Who Were the Shudras?, Ambedkar tried to explain the formation of untouchables. He saw Shudras and Ati Shudras who form the lowest caste in the ritual hierarchy of the caste system, as separate from Untouchables. Ambedkar oversaw the transformation of his political party into the Scheduled Castes Federation, although it performed poorly in the 1946 elections for Constituent Assembly of India. Later he was elected into the constituent assembly of Bengal where Muslim League was in power.[2]

Ambedkar contested in the Bombay North first Indian General Election of 1952, but lost to his former assistant and Congress Party candidate Narayan Kajrolkar. Ambedkar became a member of Rajya Sabha, probably an appointed member. He tried to enter Lok Sabha again in the by-election of 1954 from Bhandara, but he placed third (the Congress Party won). By the time of the second general election in 1957, Ambedkar had died.

Ambedkar also criticised Islamic practice in South Asia. While justifying the Partition of India, he condemned child marriage and the mistreatment of women in Muslim society.

No words can adequately express the great and many evils of polygamy and concubinage, and especially as a source of misery to a Muslim woman. Take the caste system. Everybody infers that Islam must be free from slavery and caste. [...] [While slavery existed], much of its support was derived from Islam and Islamic countries. While the prescriptions by the Prophet regarding the just and humane treatment of slaves contained in the Koran are praiseworthy, there is nothing whatever in Islam that lends support to the abolition of this curse. But if slavery has gone, caste among Musalmans [Muslims] has remained.[74]

Drafting India's Constitution

Ambedkar, chairman of the Drafting Committee, presenting the final draft of the Indian Constitution to Rajendra Prasad on 25 November 1949.

Upon India's independence on 15 August 1947, the new Congress-led government invited Ambedkar to serve as the nation's first Law Minister, which he accepted. On 29 August, he was appointed Chairman of the Constitution Drafting Committee, and was appointed by the Assembly to write India's new Constitution.[75]

Granville Austin described the Indian Constitution drafted by Ambedkar as 'first and foremost a social document'. 'The majority of India's constitutional provisions are either directly arrived at furthering the aim of social revolution or attempt to foster this revolution by establishing conditions necessary for its achievement.'[76]

The text prepared by Ambedkar provided constitutional guarantees and protections for a wide range of civil liberties for individual citizens, including freedom of religion, the abolition of untouchability, and the outlawing of all forms of discrimination. Ambedkar argued for extensive economic and social rights for women, and won the Assembly's support for introducing a system of reservations of jobs in the civil services, schools and colleges for members of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes and Other Backward Class, a system akin to affirmative action. India's lawmakers hoped to eradicate the socio-economic inequalities and lack of opportunities for India's depressed classes through these measures.[77] The Constitution was adopted on 26 November 1949 by the Constituent Assembly.[78]

Opposition to Article 370

Ambedkar opposed Article 370 of the Constitution of India, which granted a special status to the State of Jammu and Kashmir, and which was included against his wishes. Balraj Madhok reportedly said, Ambedkar had clearly told the Kashmiri leader, Sheikh Abdullah: "You wish India should protect your borders, she should build roads in your area, she should supply you food grains, and Kashmir should get equal status as India. But Government of India should have only limited powers and Indian people should have no rights in Kashmir. To give consent to this proposal, would be a treacherous thing against the interests of India and I, as the Law Minister of India, will never do it." Then Sk. Abdullah approached Nehru, who directed him to Gopal Swami Ayyangar, who in turn approached Sardar Patel, saying Nehru had promised Sk. Abdullah the special status. Patel got the Article passed while Nehru was on a foreign tour. On the day the article came up for discussion, Ambedkar did not reply to questions on it but did participate on other articles. All arguments were done by Krishna Swami Ayyangar.[79][80]

Support to Uniform Civil Code

I personally do not understand why religion should be given this vast, expansive jurisdiction, so as to cover the whole of life and to prevent the legislature from encroaching upon that field. After all, what are we having this liberty for? We are having this liberty in order to reform our social system, which is so full of inequities, discriminations and other things, which conflict with our fundamental rights.[81]

During the debates in the Constituent Assembly, Ambedkar demonstrated his will to reform Indian society by recommending the adoption of a Uniform Civil Code.[82][83] Ambedkar resigned from the cabinet in 1951, when parliament stalled his draft of the Hindu Code Bill, which sought to enshrine gender equality in the laws of inheritance and marriage.[84] Ambedkar independently contested an election in 1952 to the lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha, but was defeated in the Bombay (North Central) constituency by a little-known Narayan Sadoba Kajrolkar, who polled 138,137 votes compared to Ambedkar's 123,576.[85][86][87] He was appointed to the upper house, of parliament, the Rajya Sabha in March 1952 and would remain as member till death.[88]

Economic planning

Ambedkar was the first Indian to pursue a doctorate in economics abroad.[89] He argued that industrialisation and agricultural growth could enhance the Indian economy.[90] He stressed investment in agriculture as the primary industry of India.[citation needed] According to Sharad Pawar, Ambedkar’s vision helped the government to achieve its food security goal.[91] Ambedkar advocated national economic and social development, stressing education, public hygiene, community health, residential facilities as the basic amenities.[90] His DSc thesis "The problem of the Rupee: Its origin and solution" (1923) examines the causes for the Rupee's fall in value.[citation needed] He proved the importance of price stability over exchange stability. He analysed the silver and gold exchange rates and their effect on the economy, and found the reasons for the failure of British India's public treasury.[citation needed] He calculated the loss of development caused by British rule.[92]

In 1951, Ambedkar established the Finance Commission of India. He opposed income tax for low-income groups. He contributed in Land Revenue Tax and excise duty policies to stabilise the economy.[citation needed] He played an important role in land reform and the state economic development.[93] According to him, the caste system divided labourors and impeded economic progress. He emphasised a free economy with a stable Rupee which India has adopted recently.[citation needed] He advocated birth control to develop the Indian economy, and this has been adopted by Indian government as national policy for family planning. He emphasised equal rights for women for economic development.[citation needed] He laid the foundation of industrial relations after Indian independence.[93]

Reserve Bank of India

Ambedkar was trained as an economist, and was a professional economist until 1921, when he became a political leader. He wrote three scholarly books on economics:

• Administration and Finance of the East India Company

• The Evolution of Provincial Finance in British India

• The Problem of the Rupee: Its Origin and Its Solution[94][95][96]

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI), was based on the ideas that Ambedkar presented to the Hilton Young Commission.[94][96][97][98]