Part 2 of 3

Tharchin stayed in Yatung for the next four months, assisting Mrs. Macdonald with her English and Hindi school for the children of British officers stationed there, before pressing on deeper into Tibet toward Gyantse, the first major city between the Tibetan border and Lhasa. No sooner had he arrived than word of his activities in Yatung reached the ears of British officials stationed in Gyantse, and they requested that he open a similar school there. Despite the lack of funds, Tharchin obliged and began instructing the children of British officers and Tibetan aristocrats -- as well as a few Tibetan officials21 -- in English and Hindustanti (Hindi). The school was initially a success, but Tharchin's construction of an unabasedly Christian curriculum -- including morning prayers, Christian hymns, and Bible readings -- would eventually doom it to closure when its thinly veiled proselytizing enterprise became apparent to the Tibetan government,22 which then opened a new school in Gyantse with British help (though similar charges would shortly doom it as well). Though not invested in the schools financially, the British authorities viewed these closures as a bad sign, with one officer remarking that the Tibetans "will regret this decision one day when they are Chinese slaves once more, as they assuredly will be."23 Nonetheless, Tharchin remained in Gyantse for two more years, teaching and assisting in the translation of Hindi and English military manuals into Tibetan for the newly formed Tibetan army.24

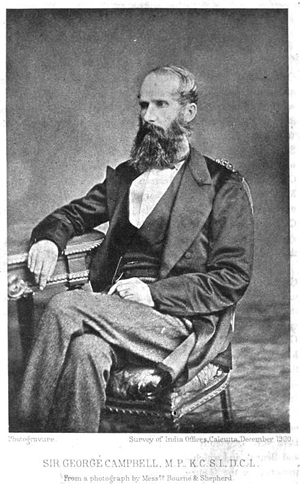

It was during this time as well that Tharchin began to forge friendships with many of the high-ranking Tibetan and British dignitaries who passed through Gyantse on a regular basis, including Sir Charles Bell; the renounced King of Sikkim, Taring Raja; and various current and future members of the Tibetan government, including members of the cabinet and national assembly,25 as well as relatives of the various aristocratic houses. Although this period would prove crucial to Tharchin's future, granting him access to all levels of government and rendering him famously influential, his proselytizing behavior was not always appreciated, least of all by the British, whose reactions ran the gamut from nervous tolerance to outright contempt.26

Satisfied with the level of language instruction they were receiving, the Tibetan officials under Tharchin's tutelage invited him to return to Lhasa with them, and in September 1923, Tharchin made his first trip to the capital city as their guest. It was there, while living across the street with Dorje Theiji, that Tharchin met his wife, Karma Dechen. Within a few months, Tharchin had secured her parents' permission to marry; shortly thereafter, they returned to India via Gangtok, where Tharchin served as translator for Dorje Theji while the latter attended military school. 27 Tharchin would later speak glowingly of this time; far more significant, however, was that in the midst of these activities he began work on what would be his greatest achievement and eventually earn him worldwide fame.

In August 1925, while working for Sutherland's successor at the Scottish Union Mission [Scottish Universities' Mission? [SUM?]], John Graham, Tharchin noticed "a Roneo Duplicator lying idle" and asked if he could take it, thinking to produce his own newspaper in Tibetan. Graham offered it to Tharchin, though with little encouragement, saying that his office staff had failed to get it working the entire time they had had it. Nonetheless, Tharchin began tinkering with the duplicator and after two months of effort in his spare time, finally got it to work. On October 10, 1925, Tharchin produced the first issue of his very own Tibetan language newspaper,

The Mirror -- News From Various Regions.28 After a brief hiatus, he commenced regular publication the following February with monthly issues. Although he received encouragement and advice from all around, his first real commendation came a year later, when he received a letter from His Holiness the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, accompanied by a gift of twenty rupees, stating that he was receiving Tharchin's newspaper, "was very glad and added to continue it and send more news which would be very useful to him."20

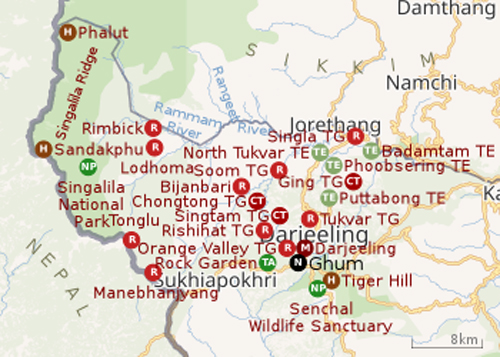

Encouraged by this, Tharchin began to think of himself more and more as a newspaperman, expanding beyond the simple relaying of news from other sources to the production of news content himself. He petitioned the Tibetan government for permission to visit Lhasa as a reporter, and on August 20, 1927, accompanied by his wife and two British civil servants, headed for Gyantse, and from there for Lhasa to conduct the first important interview of his career -- with the Thirteenth Dalai Lama. Arriving in Lhasa a month later, Tharchin remained self-conscious about his broken Tibetan -- the result of having grown up in the borderlands of Tibet -- and spent the better part of the next three months attempting to improve his speaking abilities before finally applying for an audience with His Holiness in mid-December.30 Tharchin and his wife returned to India the following February (1928), receiving 100 rupees along the way from the British Political Officer at Gyantse, Arthur Hopkinson, to support the continued publication of the newspaper. By June, the Scottish mission had received a new litho press, which Dr. Graham made available, sending Tharchin to Calcutta to receive training in its use and allowing him to use the press to produce his newspaper as part of his official duties at the mission.31 This clear links between the newspaper and missionary activities was not lost on some, and Tharchin's good fortune proved to be a mixed blessing, as many came to disregard and even dislike the newspaper.

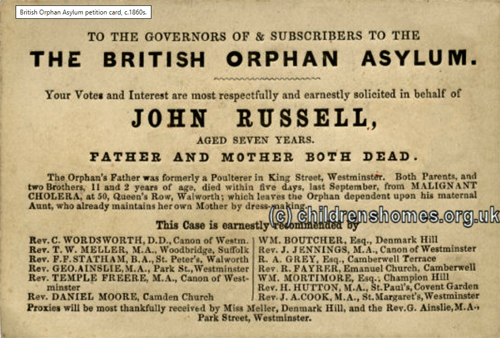

Tharchin had begun his newspaper with only fourteen subscriptions, and by the third year his subscriptions were close to fifty. But he was still sending more than a hundred free copies to officials in the Tibetan government, although more than half were usually "lost" along the way by the Tibetan post office. These, however, were the least of Tharchin's troubles. Greater difficulties during these years came from more hard-line missionaries who would soon appear in Kalimpong, in particular, Dr. Graham's replacement at the mission, the Australian Reverence Knox. Despite the often prominent "articles" on Christianity that regularly appeared in the pages of

The Mirror, Knox was not favorably disposed to Tharchin's activities as a newspaper editor, and shortly after arriving in Kalimpong brought an end to the subsidization of the paper in terms of both material resources and Tharchin's time.32 By the early 1930s, Tharchin had managed to stabilize the publication of his newspaper, although he was constantly in search of new subscribers and advertising to underwrite his costs.33 It was thus with a certain degree of trepidation that he rejoined the Scottish Union Mission [Scottish Universities' Mission] under Rev. Knox as "Tibetan Catechist,"34 agreeing to accept strict limits on his official activities in exchange for a salary. While there was little love lost between Tharchin and Knox, the position allowed Tharchin to continue publishing his newspaper. In the process -- though unintentionally -- he was building a community around him that would significantly alter the face of Tibetan politics, for better and worse. Just as Kalimpong was growing, his reputation seemed to grow along with it, and Tharchin finally began to benefit from this.

In 1931, the French Tibetologist Jacques Bacot arrived in Kalimpong, and making inquiries at David Macdonald's Himalayan Hotel, was directed to Tharchin as a potential assistant in his research. Bacot's interests, however, were very specialized: the recently recovered cache of eighth- to tenth-century manuscripts from the Silk Road town of Tun-huang. Having just recently edited and published Tse-ring-wang-gyel's Tibetan-Sanskrit Dictionary35 as a follow-up to his translation and study of a Tibetan grammar treatise,36 Bacot was eager to apply what he had learned to translating the early Tibetan documents now in his possession. To his disappointment, deciphering their contents was a far greater challenge than he'd thought, and without the help of a native Tibetan scholar he could proceed no further. Bacot enlisted Tharchin to help with his translations, paying him handsomely. Although together they made some additional progress, many of the passages were well beyond Tharchin's abilities too. Bacot had limited time in India and knew that it would be hopeless to attempt to finish the translations in isolation back in Paris. So although he would most likely never return to Kalimpong, he left his photographic reproductions of the texts with Tharchin, who promised to enlist the aid of others to complete their translation. Ironically, as Tharchin and Bacot struggled over the manuscripts that fall, several hundred miles north in Tibet, another would-be scholar of ancient Tibetan manuscripts was likewise in search of material and human resources to aid him in his research -- and his own work would affect Tharchin's dramatically.

Born in the late nineteenth century, Rahula Sakrtyayana had grown up in India, but was very much a product of the British educational system rather than anything indigenously Indian. Fixating on Tibet as a repository of untapped knowledge, in the summer of 1929, Sankrtyayana embarked on his first trip in search of Sanskrit manuscripts brought there close to a thousand years earlier and presumed to still be extant in the great monastic libraries. Sankrtyayana knew that prior to the rise of the “Three Great Seats”37 of learning in the early fifteenth century, the center of Buddhist knowledge and translation activities was Sakya, a small, secluded valley retreat located several hundred miles south and west of Lhasa. It was there that in the early thirteenth century the faculty of the great Buddhist university of India, Vikramalasila, had fled, seeking refuge from the Muslim invaders who had razed their university and put all its inhabitants to the sword, ending the Buddhist intellectual dominance of the Indian subcontinent. It was also at Sakya that the last abbot of Vikramalasila, Sakya Sribhadra, and his entourage began teaching and collaborating with Tibetan scholars on the next great wave of translations and oral transmissions on the Tibetan plateau. For Sankrtyayana, this was the logical place to look for Sanskrit manuscripts. But after many months, he came home disappointed, having found only Tibetan manuscripts.38 Sankrtyayana had begun attempting to “restore” the Sanskrit version of one text of interest from the Tibetan, Dharmakirti’s Pramanavarttika, when he learned that the Sanskrit original had recently been discovered in Nepal. Reinspired, he began planning a second trip.

By 1934, Sankrtyayana was better informed, and having identified Ngor and Shalu monasteries as likely places with Sanskrit manuscripts, he was ready to visit Tibet again.39 This time, however, he was searching not only for rare manuscripts but also, just as important, for a scholar or two who could assist him in his studies, so he went first to Lhasa. While staying there, he developed friendships with various members of the aristocratic families and ruling officials of Tibet. With the assistance of the sons of the house of Surkhang, Reting Rinpoche, and the Kalon Lama,40 Sankrtyayana’s second trip achieved success before even setting foot in a monastic library, as he was also able to acquire photographs of manuscripts from Kundeling Monastery right in Lhasa itself.

Not without justification, Sankrtyayana thought of himself as a scholar of the heyday of Buddhist India, the “Buddhist millennium” spanning from the time of Nagarjuna in the second century C.E. to the destruction of the great centers of learning in the early thirteenth century. Although many of the oral traditions from this time still survived in Tibet – a difficult source to access – the literary legacy of Buddhist India was encapsulated in the second half of the Tibetan Buddhist canon, the Tengyur.41 In the early twentieth century in Tibet, one man stood out as the foremost authority on the canon, having earlier been deputized by the Thirteenth Dalai Lama to redact the first half, the Kangyur,42 for publication in Lhasa: Dobi Geshe Sherap Gyatso.43 Before even meeting him, Sankrtyayana thought that Geshe Sherap Gyatso would be the ideal collaborator in his research. A scholar at Drepund Monastic University west of Lhasa, Geshe Sherap Gyatso was not only one of the greatest scholars of the twentieth century produced by that institution but also a key political figure of the day. Although Geshe Sherap Gyatso was unable to help Sankrtyayana personally in the way he wished, he recommended instead that Sankrtyayana consider working with his most promising – and at times, most troublesome44 – student, a young man from northeastern Tibet (Amdo) named Gedun Chope.45 Just how confident Sankrtyayana was in Geshe Sherap Gyatso’s recommendation is unclear, since he also south out the help of another recommended scholar, the tutor to the house of Tsarong, the Mongolian Geshe Chodrak46 from the great monastic university of Sera, just north of Lhasa. Geshe Chodrak also declined Sankrtyayana’s offer to come to India, but Gedun Chopel accepted, and together the two men traveled south and west toward Nepal with formal letters of authorization, stopping at various monasteries and temples along the way, such as Ngor and Shalu, in search of Sanskrit manuscripts.

By the time they reached Nepal in November 1934, Sankrtyayana and Gedun Chopel had amassed a considerable collection of Sanskrit palm-leaf manuscripts47 that they could study. Settling in Kathmandu, for the next five months they worked on cataloging and examining their finds, then left for India the following March. Abandoned by Sankrtyayana, who embarked on a trip across Southeast Asia to Japan, Gedun Chopel was left to fend for himself for more than a year in Darjeeling and greater Sikkim. Only when Gedun Chopel met Tharchin, who was still looking for someone with scholastic training to help him decipher Bacot’s Tun-huang manuscripts, did his fortunes take a turn for the better. Seeing an opportunity to secure a more stable environment, Gedun Chopel agreed to help Tharchin and moved in, living and working with him on and off for the next eighteen months, translating the early Tibetan histories from Tun-huang for Jacques Bacot.48

Despite his reliance on Tharchin, however, Gedun Chopel did not suffer for company in Kalimpong. As the economic fortunes of the Sikkimese-Tibetan border towns fluctuated, Kalimpong was slowly taking over Darjeeling as the wool-trading capital of northeast India. More than 50 percent of the wool traffic of central Tibet passed through the small town, and the economy of Lhasa became linked to the price of wool in Kalimpong. As a result, Kalimpong was quickly becoming home to a growing merchant and expatriate Tibetan population. This fact hadn’t escaped the notice of Jacques Bacot; nor did it escape the notice of another would-be Tibetan scholar, the British researcher Marco Pallis. Arriving in Kalimpong, Pallis had sought out his own Tibetan scholar to aid him in his research and found the Mongolian lama Ngawang Wangyal, whose own goals and interests had led him south as well, via Peking and Lhasa in the company of the British representative Charles Bell, for whom he had served as translator for several months.

When Theos Bernard stepped out into the streets of Kalimpong in early January 1937 with his father, this was the world he walked into. A town that in many respects marked the northernmost limit of success in the Christian missionary assault on Tibet, Kalimpong was also the staging ground from which Tibetan scholars and their Western disciples were beginning to launch their own assaults on the countries of Europe and the Americas, bringing the insights of a Buddhist worldview to the Western world, and Theos Bernard was determined to be one of them.

That January, Theos settled into a routine of studying Tibetan with Tharchin. While this was a fine arrangement for Theos (and a financial boon to Tharchin49), Glen saw it as a waste of time, and his annoyance began to wear on Theos’s nerves even more than before. Within a week, Glen decided that it was time for him to leave. “It would be absolutely wrong for him to remain,” Theos explained to Viola, for

he is about at the point where he is going to kill every Hindu in India, not saying anything about the rest of the lives he is going to terminate. If he met one in his dreams he would throw himself completely out of bed trying to get at him. When you saw him he was an angry child; so multiply that by ten and double the total each day for every day since you have been away and you will have some idea of his present state.

As glad as Glen was to leave, Theos was even more happy to get away from his father. In addition to the trip having taken a toll on his health, Glen had a problem, however -- beyond the usual financial one. Although he had a return ticket for a ship in the Dollar Line, there was a strike on and ships were only leaving India every four months. As usual, Theos had to ask Viola to bail his father out, in addition to maintaining their "continued arrangement" for his support. Even though Glen was preparing to leave Kalimpong, Theos assured Viola that their research together would not end. Indeed, with Viola's support, Glen would be hard at work upon his return spending "all of his time wiping [sic] together some literary data that I want in order by the time I return." Just as important, Theos told Viola, with her support Glen "will also be able to continue on with the laboratory experiments which are necessary to finish up this work on Mercury which is needed for our future practice." 50

"Practice" was indeed on his mind, and all other concerns were quickly falling behind, barely worth a casual remark to Viola, Theos believed they were moving into a phase of their lives together that was centered around their work and that "life is always going to be a pace like this and there will never be enough time to find that home and have children." Having renounced that possibility, he reiterated to Viola his feeling that they should dedicate their lives to finding "some way so that others may better help themselves, and so forget that as an entity we exist," and along those lines had some recommendations for her career. Although this was only a passing comment for Theos, it was an unexpected shock to Viola.51

oblivious to the deep impact those statements would have on Viola as a reversal of his earlier promises, Theos was caught up in his world of studies, having settled into a stable routine at the hotel:

5 am: Awake; practice yoga/pranayama

7 am: Tibetan lesson with Tharchin; followed by mile walk, a light breakfast of oatmeal and milk, and studies

Noon: Lunch and errands, followed by studies

4 pm: Tea time and review

5 pm: Tibetan lesson with Tharchin again

6:30 pm: Washing, more yoga exercises, and study

9 pm: Reading, or writing to Viola

11 pm: Sleep

With Glen finally gone, there was little to distract Theos, and he remained confident that he could master Tibetan with ease, and since it was "only a matter of time and routine;' he soon "would have a working knowledge of it." This was important, because beyond gaining the ability to access the content of Tibetan texts himself, the ability to claim knowledge of Tibetan would be crucial in gaining admittance to Oxford University. William McGovern's observation that learning Tibetan meant learning three different "languages" because "there is not only an ordinary and an honorific language, but also a high honorific language used in addressing high dignitaries"52 was, in fact, quite true, and Theos feared that he would have little time for letter writing to anyone besides Viola.

Although he thought that he could easily lose himself "here for the next fifty years in work and never know there was an outside world," nonetheless, she shouldn't worry too much about him losing his perspective:

Do not take it that I feel that the purpose of life is to learn a language or become versed in the Tibetan literature -- those two things are just as worthless as a million other things that man is playing with so far as his real purpose is concerned. I only dabble with this form because I believe that behind it there is some information that I can use to better enable me to continue on with my other work.

This was the real reason, he told her, that he never had done "a great deal of talking about the real inner development to be derived from Yoga" because he "did not want to talk without having had first hand personal experience with it." But in the absence of direct guidance and authentic commentaries, getting that experience would prove difficult. Nonetheless, Theos took encouragement when and where he could, even being allowed to photograph a Tibetan text belonging to Tharchin, with figures illustrating different yogic exercises.53

But many of these issues, Theos recognized, were long-term concerns. In the short term, he had received most of the knowledge that he needed from his father, and the rest was clearly explained in the pamphlets they had gotten from Kuvalavananda. Solidly engaged in those exercises. he was pleased to tell Viola that in addition to his language studies, his practice of the yogic exercises was progressing; working on his breathing exercises (pranayama), he had gotten to the point where his uddiyana bandha54 was "up to its highest form of perfect" -- something Viola had yet to see -- and he promised he would demonstrate it for her on his return, While all these developments provided positive reinforcement to Theos,

one of the thrills of the entire adventure has been the following of the footsteps of those that I have read about for so long -- David-Neel, McGovern, Sir Charles Bell, David Macdonald who I have come to know as a real friend, and all the members of the Everest Expeditions .... The field is so vast and those who have been combing it are of such a variety and interest that there is yet an unlimited quantity of material for me whose background is so entirely different. They have all told what there is to find, but no one has revealed what lies behind that which exists, and here is my task.

His challenge, as he saw it, was to "prove to others the real concrete aspects of this philosophy which is nothing but an explanation of the functioning of nature." But Theos thought all of this was exciting because he found it a stark contrast to his life in America and the obligations imposed on him by American society. It was an inner conflict that was causing him to waffle between excitement and frustration:

I am out for a Ph.D. and for some God for known reason I have chosen the most remote thing that we know of for its subject; so now that I have started, I must see it thru to the bitter end regardless of how much it hurts ... that is why I am here -- to work and find out how much of what I believe really exist[s] ... [but] if I did not have to have a degree, I have my doubts as to how long I would stay here. I do not care as much about the degree, but the public does, and I care about the public to a certain extent, therefore it is essential that I come up to what they call a standard, before 1 tell all to go to hell and do as 1 please about anything and everything. All I want to do is meet their requirements. Mine are much higher, but they do not understand them; so again, I must do the adjusting. And then to top off the distrust of the public, [ have its nest in my home, for Viola doesn't give a dam [sic] about it, just as I don't give a dam about medicine.55

For Theos, this was a wonderful thing -- the fact that they were "separate individuals" and yet had a love that couldn't be found elsewhere, with only "minor differences" between them. But when Theos's letter arrived, Viola was not amused by his comments. Minor differences? "Like hell they are!" she thought, and as fast as the mail could travel, Theos had Viola's response and once again had to work to repair the damage to their relationship. ''There is nothing that hurts me worse to feel that I have in some unknown way brought you a hurt," he wrote back. Trying to convince her that she had taken his statements "all wrong," he reassured her that "if you only knew all the love there is for you in me, you would never misinterpret things." Just the same, Theos couldn't hid his anger:

I suppose you think that I get a kick out of living away from you-what in the hell did I change the course of my life and marry you for if I wanted to get away from you. You also indicate that you feel that my whole choice of action is a bit queer -- well, I have to do something in this world, we all cannot be doctors.

But venting at Viola would solve little, he knew -- even if that realization didn't stop him -- so he suggested, "I feel that it is best for us to dispense with the writing and know that we have a complete understand[ing] over all of these things," while attempting to assuage her anger by saying that if they persisted in their long-distance argument it would be "likely to cause us a little trouble which is quite unnecessary, for our adjustment is perfect and will more than carry us on thru a life of continual happiness." Turning philosophical, as he usually did at such times, he reminded her that "our whole society is pretty rotten and that civilization on the whole is man's most highly perfected machine for his own destruction."

Theos sent his letter immediately, but by the next day had decided that a further apology was probably necessary, telling her, "I have been having my mood." More important, Theos tried to convince Viola that not only was it bad for their relationship in the long term for her to misunderstand him, but also it had an adverse effect on him in the present: "you always read or listen to my words and never hear what my heart is crying out," and "it is a hell of a feeling to have everything shot to hell and then realize that the only place that can be called home is the ground that you stand on for the moment." For without her, he told Viola, he was lost, but even with her, the future remained uncertain. "I wonder if there is any way of telling what on earth I will be doing five years from now," he wrote. "Hell, I bet that I do not even die regularly -- probably alone someplace, mad as hell at myself for being there." But, having run the gamut of his all too typical range of emotions, in the end, as always, he reaffirmed his undying love for her -- as Theos always chose to expressed it, "I lub OO OOoo."

How, precisely, all of these concerns would play out, Viola could not tell, so she chose to respond to all of Theos's conflicting signals, the expressions of his "dammed good for-nothing emotional nature," by putting such discussions on hold -- at Theos's request -- for the benefit of his state of mind until such time as they were reunited. After and despite it all, Viola reminded herself that she did love him, and he did seem lonely and very miserable.

As the weeks passed, Theos's spirits slowly recovered and his mood began to improve as the Tibetan New Year approached. When he met Tharchin for his daily morning Tibetan lesson, the comings and goings of various people for the holiday meant that Theos was introduced to many new faces. One man who stopped by to convey his greetings to Tharchin was a young Kalmyk Mongolian lama, Ngawang Wangyal. Wearing a traditional Mongolian monk's robes and a somewhat incongruous homburg hat,56 Wangyal made an immediate impression, He was, as Theos would find out, a brilliant scholar who had already played many roles over the course of his life.

Born to Mongolian parents in the Kalmyk region of Russia57 at the turn of the century, Wangyal had entered his local monastery at the age of six, joining his older brother, Kunsang, who began tutoring him. By the time he was sixteen, his interests had turned to medicine and he relocated to a medical college in Outer Mongolia, where he began studying the Tibetan medical tradition. After a year, however, his teacher suddenly passed away, and he was left stranded and directionless, for in the absence of his teacher, his interest in medicine quickly faded. To his good fortune, the Bolshevik revolution had just taken place in Russia, sending a group of Buryat Mongolian Buddhists south to attempt to secure sovereignty for the Mongolian peoples. Among them were the abbot of the Petrograd temple, Sodnom zhigzhitov; the notable Buryat intellectual Badzar Baradinevich Baradin; and the foremost Buddhist in all of Russia, onetime tutor to the Thirteenth Dalai Lama, and advisor to Tzar Nicholas II, Agwan Dorjiev -- whose presence in Lhasa at the turn of the century had made the British Raj so nervous. Although he hailed from Mongolian Buryatia in Siberia, Dorjiev had maintained a commitment to the Kalmyk Mongolians and was famous among them, often visiting Kalmykia and even establishing two colleges there for the study of Buddhism. Hearing of Wangyal's abilities as a student, Dorjiev took him on as a disciple and eventually decided to bring him along to Lhasa to ensure that his studies continued.

Thus accompanied by Buryat Russian political spies and secret emissaries, 58 Wangyal arrived in Tibet and settled into Drepung Monastic University, home to many Mongolian monks in Lhasa, and, like Dorjiev and so many other Mongolians before him, entered its Gomang College. Trained well by his teachers, the young Ngawang Wangyal completed his studies in half the time of his fellow Tibetan students by doubling his lessons. When his studies were finished, feeling homesick for Mongolia, by the late 1920s Wangyal was ready to return home for a while. Making his way to Peiping (Beijing), he had the good fortune to meet some Buryat monks who advised him to proceed no further. The Bolsheviks had begun to exert their complete authority over Russia and his Mongolian homeland and in every area under their control Buddhists -- and monks in particular -- were being persecuted. He was advised not even to contact his family, since doing so could put them at risk, Although he had no way of knowing, such difficulties had already touched his family, Kunsang, his older brother who had been such a formative influence on him as a young boy, had risen to the post of abbot of his monastery, only to be arrested by the Bolsheviks. Already in prison before Wangyal had even completed his studies. Kunsang would die there without the brothers ever seeing each other again.

Heeding the advice of his fellow monks, Wangyal decided to stay in China. Finding work as a translator for Russian scholars and as a teacher among his fellow Mongolians, he learned English in the process, and was sufficiently fluent in so short a time that he was able to serve as translator for the British Political Officer, Charles Bell, when he visited Mongolia, China, and Manchuria. Although Wangyal's studies in Tibet were completed, one of the requirements for the geshe degree was the obligation to feed one's home monastery for a day. As Drepung had a population of over 7,000 monks, this was no small feat, especially for a Mongolian far from home. With the money he earned in China during those years, Wangyal was eventually able to return to Lhasa, but initially did not want to fulfill the final obligations to his monastery in order to obtain his degree, even if he'd had the money, which he didn't, Feeling that the system had become corrupt, he, like his teacher Agwan DoIjiev, thought than too many monks and geshes weren't really studying. Worse yet, men he considered to be the really great teachers -- like Geshe She rap Gyatso, who had been driven out of Lhasa for daring to edit the canon, or his own teacher, Geshe Jinpa, who, poverty stricken, was living in the basement of Gomang College-were not receiving the respect and support that they deserved. Consequently, Wangyal felt that a geshe degree was no longer a hallmark of knowledge and attainment, but rather proof of having bought a lot of tea and made good aristocratic connections. The Pha-la family, however, who had been his friends, insisted that he go through with the process, going so far as to cover the cost of feeding his monastery. Even so, Geshe Wangyal eventually left Lhasa and made his way to India. At thirty-five, he was only a few years older than Theos when they met in Kalimpong. Having mastered Tibetan and Russian over his native Mongolian, Wangyal had English fluency that, though limited, was more than good enough for most conversations.

Theos and Geshe Wangyal immediately struck up a friendship, which Theos's interest in Tibetan literature only strengthened. Relaxing in Tharchin's home, they had a long conversation about the Tibetan canon and the educational system in the great monastic universities. Geshe Wangyal explained that he had agreed to work with Marco Pallis and would return to England with him at the end of his visit in a few months. Eager to learn about potential research partners for when he returned home, Theos quizzed Geshe Wangyal at length about where and in what texts he could find the answers to many of his research questions, and was duly impressed by the answers. "He is a fine chap," Theos wrote to Viola, "but now he is pretty naive so far as the world is concerned but he has covered a vast amount of literature in his own field and I have found him extremely helpful in telling me where certain kinds of information can be found."

Although Geshe Wangyal had only agreed to go to England with the tentative possibility of guiding Marco Pallis back to Tibet, he would rather return to China, he told Theos. "His favorite stop is Peking and he wishes to eventually get back there to do more studying." Since such a journey from England would be more easily accomplished by traveling via America, without hesitation Theos invited him to visit him (or Viola, at least) should he actually reach the United States. "I have given him your address;' he told Viola, "and told him by all means that he is to call you once he arrives and that you will do whatever is possible for him .... He may never turn up, or I may be there before he is. This is just all in the way of a warning that someday a Lama might come into your life."

At the end of Tharchin's impromptu tea party, thoroughly warmed up to Theos, Geshe Wangyal insisted that he accompany him to his home to attend his New Year's party, where a number of Tibetans were gathering. Far from the sort of restrained event that British decorum imposed in Tharchin's household. Geshe Wangyal's party was host to a contingent of guests freshly arrived from Tibet -- a group of dignitaries traveling en route to China via Calcutta, along with many local well-wishers.

No less prominent than the Three Great Seats of Learning that were homes to the scholars of the Lhasa valley, the great monastic university of Tashilhunpo in Shigatse, some hundred miles southwest of Lhasa, boasted many brilliant minds and political figures as well. Not the least of these was the Panchen Lama, whose political machinations had proven too much for the central government and who as a result had spent many years in self-imposed exile in China. Political instability seemed to be the theme in Europe and the rest of Asia in the 1930s, and Tibet was no exception. While the Bolsheviks to the north, the Chinese communists to the east, and the British to the south fought their opponents in both the physical and political arenas, all eyed Tibet as the key to controlling central Asia. Seeing the potential for the downfall of his beloved country, the Thirteenth Dalai Lama -- the "Great Thirteenth," as he came to be called -- had tried to modernize Tibet while maintaining its independence from the three surrounding empires.

With different factions in the monastic and aristocratic ranks all clamoring for influence, there was a constant power struggle among pro-British, pro-Chinese, and isolationist groups in Tibet throughout the first few decades of the twentieth century. The Panchen Lama and Tashilhunpo Monastery, always having had strong ties to China -- from which they benefited financially -- had supported the brief Chinese occupation of Tibet and seizure of the Lhasa government from 1909 to 1912. As the situation continued to heat up, ten years later the Ninth Panchen Lama would have to flee for his life. But the sudden death of the Great Thirteenth in December 1934 left a power vacuum at the highest levels in Tibet, and with a contingent of three hundred Chinese soldiers and the backing of the Chinese Republican government, the Panchen Lama was trying to return to Tibet and in particular, it was feared, to Lhasa to take control of the government. Having thrown out a failed Chinese invasion of Tibet twenty-five years earlier, Tibetans talked of renewed Chinese aspirations to take Eastern Tibet (Kham) and convert it into a Chinese province.59 There were rumors that the Panchen Lama had his own candidate for the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, whom he had identified himself and had traveling with him in his entourage. Even if all these things were untrue, fearing the leverage that any of them would give the Chinese government over Tibet, the Tibetan government chose active opposition, and by 1937 the Panchen Lama and his party had been stalled on the other side of an active skirmish line on the Tibetan-Chinese border. For several years he had been biding his time, awaiting resolution of the dispute.

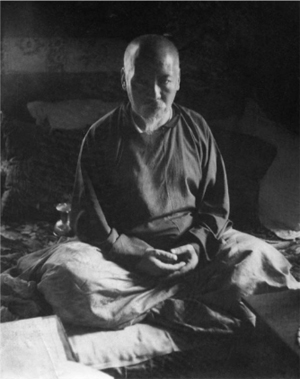

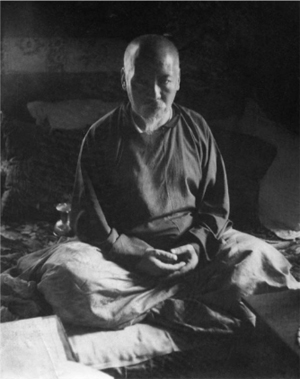

Eager to see the situation resolved, the British Mission in Lhasa had been advising negotiations between the Lhasa government and the Panchen Lama, the latter choosing as his intermediary his associate in self-imposed exile, the Ta Lama, Ngak-chen Rinpoche. Quite a few notables had joined him on his circuitous trip to rendezvous with the Panchen Lama in Kye-gudo, including the semiofficial Republican envoy to Tibet in Lhasa, Madame Liu Manqing.60 Sitting in that small room with Theos in Kalimpong were Ngak-chen Rinpoche, Geshe Sherap Gyatso, and various members of Ngakchen Rinpoche's entourage -- a formidable party.

Ta Lama Ngak-chen Rinpoche, Losang Tenzin Jigme Wangchuk,61 was a descendant of the family of the Tenth Dalai Lama, educated at Tashilhunpo Monastery. When the Ninth Panchen Lama had fled Tibet in 1923, Ngak-chen Rinpoche had accompanied him, and they traveled throughout China giving teachings and empowerments. He had returned to Lhasa in 1931 and again in 1933, but by 1937 little progress had been made in resolving the stand-off between the factions, and so Ngak-chen Rinpoche had left Lhasa -- some say he was dismissed and recalled -- in the company of the Chinese representative, to rejoin the Panchen Lama on the Tibetan-Chinese border.

Traveling with him was a close friend of the late Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Geshe Sherap Gyatso, the scholar from Drepung who had been the editor of the most recent redaction of the Buddhist canon. Following the death of the Great Thirteenth, his political enemies had moved against him and he had decided to abandon his life in Tibet and go to China, ostensibly to translate his redaction of the Tibetan Buddhist canon into Chinese.62

Finally, Theos thought, he was making real progress; finally, he was beginning to interact in real Tibetan circles. For although the Tibetan expatriates and traders who populated Kalimpong were a pleasant enough group, the relentless proselytizing by the local missionaries had reduced many of them to a less than respectable state. Writing to a friend who had recently professed his belief in Christianity, Theos informed him that the faith "had reduced itself here to a handful of Devil Chasers preaching in elegant stone houses of superstition to a congregation of Money Christians," for that was about what it amounted to in Kalimpong in Theos's eyes. "The Tibetans are good Christians as long as there is a chance to make a little money or have something nice given to them," he continued, "but they all have their Buddha at home." Here now, however, were Tibetans with no such pretenses.

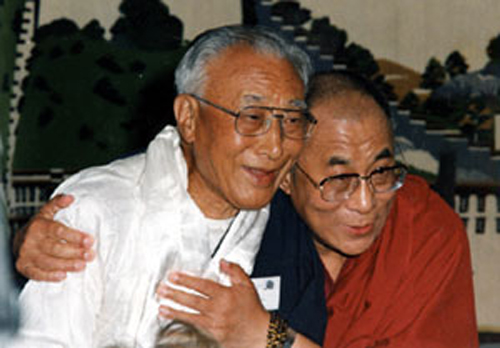

Figure 7.1. Ngak-chen Rinpoche (PAHM)

Figure 7.1. Ngak-chen Rinpoche (PAHM)From the positive impression he made on the assembled notables, a few days later Theos received an invitation to dinner from one of the aristocratic families that maintained a house in Kalimpong. Tsarong Lhacham -- Lady Tsarong -- the wife of the famous Tibetan general and former cabinet minister Tsarong shape, was in Kalimpong, and hearing about Theos, she invited him over for a meal. Although Theos thought little of it at the time -- beyond the details of the food itself and how it "played havoc" with his diet regimen -- this meeting would prove his most important connection within Tibet.

A couple of weeks later, the entourage of Ngak-chen Rinpoche was on the move again, south to Calcutta to board a ship for China. Though he did not plan on doing so, Theos would soon be reunited with them in Calcutta, for one morning a passing report in the morning newspaper sparked his imagination: a conference was scheduled to take place there soon. But this was no ordinary conference.

"To keep count of thousands of paces," the semifictional Hurree Babu explained to his pupil, there was "nothing more valuable than a rosary of eighty-one or a hundred and eight beads, for it was divisible and sub-divisible into many multiples and sub-multiples."63 When it was first published at the opening of the twentieth century, Rudyard Kipling's Kim was both hailed as a wonderful piece of literature and derided as the ultimate testament to the colonial fantasy, an idealized representation of life in "the Great Game." To those in the know, however, Kim was little more than a lightly fictionalized account of the actual sort of intrigues afoot in British India, such as those of Sarat Chandra Das ("Hurree Chunder Mookherjee"), Tibetan scholar and British spy.64 Das, a slightly rotund Bengali like Kipling's Mookerjee, had employed the very techniques described in Kipling's work in the early 1880s, traveling with a Tibetan lama65 from an outlying monastery as part of his disguise while laying the groundwork for a military invasion being planned by the more ambitious elements within the British Raj. "We had given ourselves out to be pilgrims," wrote Sarat Chandra Das,66 and though published within years of each of his trips, his works were not widely available, their circulation having been restricted by the Indian British authorities as a security risk.

Only slightly more than twenty years after Das's initial surveys of the southern passes and valleys, India's Viceroy, Lord Curzon, sent an army into Tibet, ostensibly to secure the release of two British Sikkimese spies captured there. As a result, in December 1903, the recently promoted Colonel Younghusband led his small army -- 2,000 infantry, 10,000 coolies, 7,000 mules, 4,000 yaks, and five newspaper correspondents67 -- up over the Jelapla Pass from Sikkim into Tibet, and after fighting a series of embarrassing and regrettably bloody battles,68 proceeded north toward Lhasa. Though aimed at stabilizing relations with the nation of Tibet, ironically, this confluence of events -- Agvan Dorjiev's emissary to the court of the Dalai Lama, British fears of Russian penetration into that Himalayan kingdom, and the obvious irrelevance and ineffectualness of Chinese representation in Lhasa -- produced levels of colonialist paranoia that served to mark independent Tibet as doomed, a prize destined to be swallowed by one of her aggressive imperialist neighbors.

Younghusband himself viewed his activities at the time entirely within the scope of his duties to the empire, remarking shortly after his return that he and his comrades "may have nasty jobs to do but it is the game and they will play it through."69 In February 1937, the Younghusband who was about to arrive in Calcutta was a very different man from who he had been in those days, for the years had transformed him -- like the occasional few who saw too closely the toll of death their campaigns had taken -- from unrepentant man of war to unrepentant man of peace. Younghusband himself attributed this change to the influence of a Tibetan lama he had met while in Tibet, the eighty-sixth Regent of Ganden Monastery (the Ganden Tri-pa), Tsang-pa Lo-sang-gyal-tsen,70 who had assumed the Regency of Tibet when the Thirteenth Dalai Lama fled the advancing British army and had served as the Tibetan government's chief negotiator. Comparing the Regent to the Tibetan lama in Kipling's Kim, Younghusband remarked that he was "an old and much respected Lama ... a cultured, pleasant-mannered, amiable old gentleman, with a kindly, benevolent expression." On his last full day in Lhasa, Younghusband was visited one last time by the Ganden Tri-pa, who presented him with a small bronze statue of the Buddha, telling him, "when we Buddhists look on this figure we think only of peace, and I want you, when you look at it, to think kindly of Tibet." Recounting his time in Tibet, Younghusband later wrote that he took some time for himself just before leaving and "went alone up onto the mountain side and in the holy calm of eventide I chewed the cud of all I had just experienced."

I was naturally elated at the successful ending of a critical mission. But suddenly, as I sat there among the mountains, bathed in the glow of sunset, there came upon me what was far more than elation or exhilaration ... I was beside myself with an intensity of joy, such as even the joy of first love can only give a faint foreshadowing of. And with this indescribable and almost unbearable joy came a revelation of the essential goodness of the world. I was convinced past all refutation that men at heart were good, that the evil in them was superficial, that the main impulse in them was to the good -- in short, that men at heart were divine.71

Rising early the next morning, he carefully placed the statue of the Buddha in his saddlebag, and looking out over the early morning skies and distant peaks of the Himalayas, headed out calm and contented in the wake of his deep religious epiphany.

By the spring of 1937, while most of Europe braced for another war, it was this Younghusband, a religious man of peace, who was organizing a "World Congress of Faiths" in Calcutta. Following the 1893 World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, the theme of religious ecumenicalism spurred a number of gatherings and conferences over the subsequent decades, and now Younghusband himself had taken up the challenge of promoting world peace and interreligious dialogue. "The aim and purpose of this Congress," it was declared,

is to promote a spirit of fellowship among mankind through religion and develop a world-loyalty while allowing full play for the diversity of men, nations and faiths. The Congress does not emphasise that all religions are alike, nor does it wish to formulate a synthetic faith out of the various elements contributed by the different religions, but seeks to engender a spirit of fellowship between the religions as they are, in their common attempt to solve the problems of humanity.72

Having hosted a similar meeting in England the year before, Younghusband set his sights on India, hoping to return to those lands for the first time in decades.

Excited by the prospect of meeting Younghusband, Theos prevailed upon David Macdonald to accompany him to Calcutta to attend the conference, offering to cover any and all expenses if he would introduce him to the esteemed knight,73 Not having seen Younghusband in many years and with little likelihood of any future opportunity to do so, Macdonald accepted and the two men headed south for Calcutta. After they checked into rooms at his favorite abode, the Great Eastern Hotel, Theos began strategizing for the days ahead. Just as they arrived in Calcutta, the newspapers were announcing even more exciting news concerning the conference: not only was Sir Francis Younghusband returning to India, but he was also being transported and accompanied by his friend and neighbor, Charles Lindbergh. Seizing the opportunity before him, Theos suggested to David Macdonald that they invite their old and new friends for lunch just prior to the start of the conference. Eager for a reunion, Younghusband accepted the invitation. and Ngak-chen Rinpoche, having shaken Younghusband's hand as a young man in Lhasa in 1904, looked forward to meeting the man again. So one evening in late February there assembled in a restaurant in Calcutta an impressive gathering of men and women of power, influence, and intelligence -- Sir Francis Younghusband, Charles and Anne Lindbergh, Madame Liu Manqing and the Chinese representative accompanying the party to china, David Macdonald, Ngak-chen Rinpoche, Geshe Sherap Gyatso, and Gedun Chopel -- and in the middle of them all was Theos Bernard,14 He was beside himself, overjoyed at having met Younghusband and having struck up a friendship with Lindbergh on top of it all:

How and why did I ever have Lindbergh dining with me in Calcutta with a Lama from Tibet is just as much a mystery to me as it is to you and even he -- for he expressed the same thoughts -- why should I from Arizona, meet him in India. As it turns out he is much interested in some of these things. He expresses the desire to have a longer chat so that we should go into many of the details -- this may come to pass -- hard to say -- for we are both anxious to leave Calcutta.