Jiddu Krishnamurtiby Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/3/20

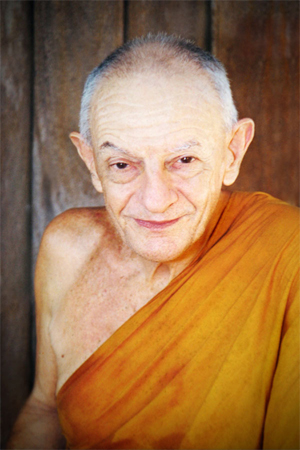

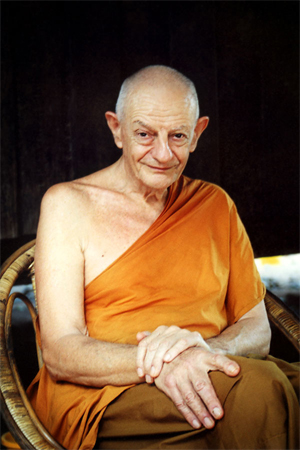

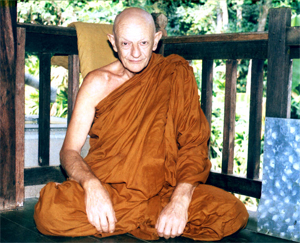

Jiddu Krishnamurti

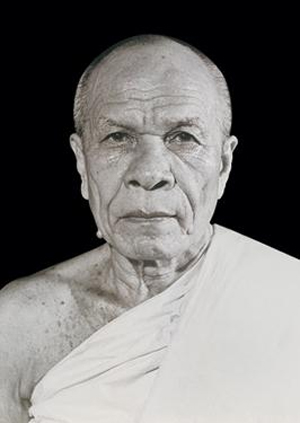

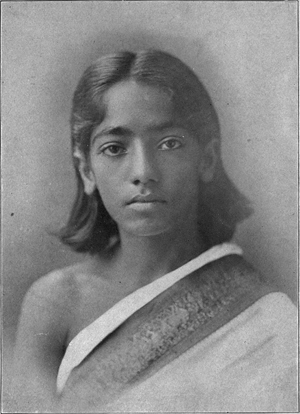

J. Krishnamurti c. 1920s

Born: 11 May 1895, Madanapalle (now Andhra Pradesh State), Madras Presidency, British India

Died: 17 February 1986 (aged 90), Ojai, California, U.S.

Occupation: Philosopher author public speaker

Parent(s): Jiddu Narayaniah and Sanjeevamma. Annie Besant and Charles Webster Leadbeater (adopted).

Jiddu Krishnamurti (/ˈdʒɪduːkrɪʃnəˈmuːrti/; 11 May 1895 – 17 February 1986) was an Indian philosopher, speaker and writer. In his early life he was groomed to be the new World Teacher but later rejected this mantle and withdrew from the Theosophy organization behind it.[1] His interests included psychological revolution, the nature of mind, meditation, inquiry, human relationships, and bringing about radical change in society. He stressed the need for a revolution in the psyche of every human being and emphasised that such revolution cannot be brought about by any external entity, be it religious, political, or social.

Krishnamurti was born in south India in what is now the modern day Madanapalle of Andhra Pradesh. In early adolescence he met occultist and theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater on the grounds of the Theosophical Society headquarters at Adyar in Madras. He was subsequently raised under the tutelage of Annie Besant and Leadbeater, leaders of the Society at the time, who believed him to be a 'vehicle' for an expected World Teacher. As a young man, he disavowed this idea and dissolved the Order of the Star in the East, an organisation that had been established to support it.

Krishnamurti said he had no allegiance to any nationality, caste, religion, or philosophy, and spent the rest of his life travelling the world, speaking to large and small groups, as well as individuals. He wrote many books, among them The First and Last Freedom, The Only Revolution, and Krishnamurti's Notebook. Many of his talks and discussions have been published. His last public talk was in Madras, India, in January 1986, a month before his death at his home in Ojai, California. His supporters — working through non-profit foundations in India, Great Britain and the United States — oversee several independent schools based on his views on education. They continue to transcribe and distribute his thousands of talks, group and individual discussions, and writings by use of a variety of media formats and languages.

Krishnamurti was unrelated to his contemporary U. G. Krishnamurti (1918–2007), although the two men had a number of meetings.[2]

Biography

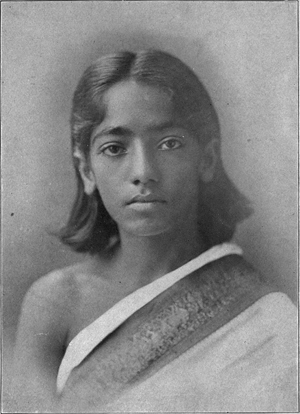

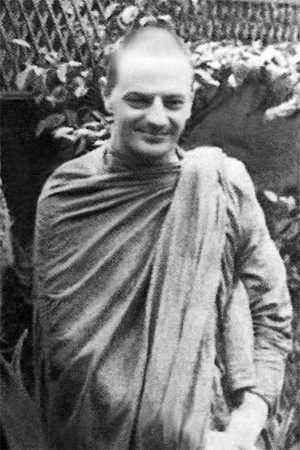

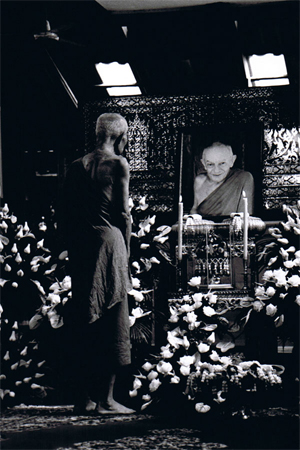

Family background and childhood Krishnamurti in 1910

Krishnamurti in 1910The date of birth of Krishnamurti is a matter of dispute. Mary Lutyens determines it to be 12 May 1895[3] but Christine Williams notes the unreliability of birth registrations in that period and that statements claiming dates ranging from 4 May 1895 to 25 May 1896 exist. He used calculations based on a published horoscope to derive a date of 11 May 1895 but "retains a measure of scepticism" about it.[4] His birthplace was the small town of Madanapalle in Madras Presidency (modern-day Chittoor District in Andhra Pradesh). He was born in a Telugu-speaking Brahmin family.[5] His father, Jiddu Narayaniah, was employed as an official of the British colonial administration. Krishnamurti was fond of his mother Sanjeevamma, who died when he was ten.[6] His parents had a total of eleven children, of whom six survived childhood.[7]

In 1903 the family settled in Cudappah, where Krishnamurti had contracted malaria during a previous stay. He would suffer recurrent bouts of the disease over many years.[8] A sensitive and sickly child, "vague and dreamy", he was often taken to be intellectually disabled, and was beaten regularly at school by his teachers and at home by his father.[9] In memoirs written when he was eighteen years old Krishnamurti described psychic experiences, such as seeing his sister, who had died in 1904, and his late mother.[10] During his childhood he developed a bond with nature that was to stay with him for the rest of his life.[11]

Krishnamurti's father retired at the end of 1907. Being of limited means he sought employment at the headquarters of the Theosophical Society at Adyar. Narayaniah had been a Theosophist since 1882. He was eventually hired by the Society as a clerk, moving there with his family in January 1909.[12] Narayaniah and his sons were at first assigned to live in a small cottage which was located just outside the society's compound.[13]

DiscoveredIn April 1909, Krishnamurti first met Charles Webster Leadbeater, who claimed clairvoyance. Leadbeater had noticed Krishnamurti on the Society's beach on the Adyar river, and was amazed by the "most wonderful aura he had ever seen, without a particle of selfishness in it."[a] Ernest Wood, an adjutant of Leadbeater's at the time, who helped Krishnamurti with his homework, considered him to be "particularly dim-witted".[15] Leadbeater was convinced that the boy would become a spiritual teacher and a great orator; the likely "vehicle for the Lord Maitreya" in Theosophical doctrine, an advanced spiritual entity periodically appearing on Earth as a World Teacher to guide the evolution of humankind.[15]

In her biography of Krishnamurti, Pupul Jayakar quotes him speaking of that period in his life some 75 years later: "The boy had always said "I will do whatever you want". There was an element of subservience, obedience. The boy was vague, uncertain, woolly; he didn't seem to care what was happening. He was like a vessel with a large hole in it, whatever was put in, went through, nothing remained."[16]

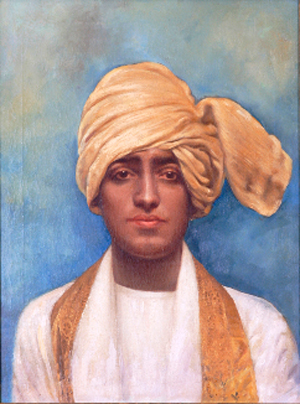

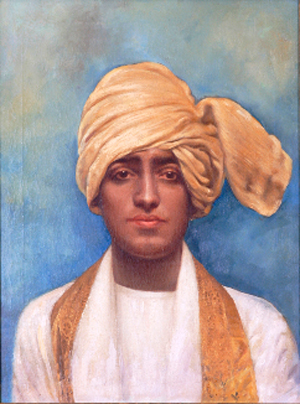

Krishnamurti by Tomás Povedano

Krishnamurti by Tomás PovedanoFollowing his discovery by Leadbeater, Krishnamurti was nurtured by the Theosophical Society in Adyar. Leadbeater and a small number of trusted associates undertook the task of educating, protecting, and generally preparing Krishnamurti as the "vehicle" of the expected World Teacher. Krishnamurti (often later called Krishnaji)[17] and his younger brother Nityananda (Nitya) were privately tutored at the Theosophical compound in Madras, and later exposed to a comparatively opulent life among a segment of European high society as they continued their education abroad. Despite his history of problems with schoolwork and concerns about his capacities and physical condition, the 14-year-old Krishnamurti was able to speak and write competently in English within six months.[18] Lutyens says that later in life Krishnamurti came to view his "discovery" as a life-saving event. When he was asked in later life what he thought would have happened to him if he had not been 'discovered' by Leadbeater he would unhesitatingly reply "I would have died".[19]

During this time Krishnamurti had developed a strong bond with Annie Besant and came to view her as a surrogate mother. His father, who had initially assented to Besant's legal guardianship of Krishnamurti,[20] was pushed into the background by the swirl of attention around his son. In 1912 he sued Besant to annul the guardianship agreement. After a protracted legal battle Besant took custody of Krishnamurti and Nitya.[21] As a result of this separation from family and home Krishnamurti and his brother (whose relationship had always been very close) became more dependent on each other, and in the following years often travelled together.[22]

In 1911 the Theosophical Society established the Order of the Star in the East (OSE) to prepare the world for the expected appearance of the World Teacher. Krishnamurti was named as its head, with senior Theosophists assigned various other positions. Membership was open to anybody who accepted the doctrine of the Coming of the World Teacher. Controversy soon erupted, both within the Theosophical Society and outside it, in Hindu circles and the Indian press.[ b]

Growing upMary Lutyens, a biographer and friend of Krishnamurti, says that there was a time when he believed that he was to become the World Teacher after correct spiritual and secular guidance and education.[23] Another biographer describes the daily program imposed on him by Leadbeater and his associates, which included rigorous exercise and sports, tutoring in a variety of school subjects, Theosophical and religious lessons, yoga and meditation, as well as instruction in proper hygiene and in the ways of British society and culture.[24] At the same time Leadbeater assumed the role of guide in a parallel mystical instruction of Krishnamurti; the existence and progress of this instruction was at the time known only to a select few.[25]

While he showed a natural aptitude in sports, Krishnamurti always had problems with formal schooling and was not academically inclined. He eventually gave up university education after several attempts at admission. He did take to foreign languages, in time speaking several with some fluency.[26]

His public image, cultivated by the Theosophists, "was to be characterized by a well-polished exterior, a sobriety of purpose, a cosmopolitan outlook and an otherworldly, almost beatific detachment in his demeanor."[27] Demonstrably, "all of these can be said to have characterized Krishnamurti's public image to the end of his life."[27] It was apparently clear early on that he "possessed an innate personal magnetism, not of a warm physical variety, but nonetheless emotive in its austerity, and inclined to inspire veneration."[28] However, as he was growing up, Krishnamurti showed signs of adolescent rebellion and emotional instability, chafing at the regimen imposed on him, visibly uncomfortable with the publicity surrounding him, and occasionally expressing doubts about the future prescribed for him.[c]

Krishnamurti in England in 1911 with his brother Nitya and the Theosophists Annie Besant and George Arundale

Krishnamurti in England in 1911 with his brother Nitya and the Theosophists Annie Besant and George ArundaleKrishnamurti and Nitya were taken to England in April 1911.[29] During this trip Krishnamurti gave his first public speech to members of the OSE in London.[30] His first writings had also started to appear, published in booklets by the Theosophical Society and in Theosophical and OSE-affiliated magazines.[31] Between 1911 and the start of World War I in 1914, the brothers visited several other European countries, always accompanied by Theosophist chaperones.[32] Meanwhile, Krishnamurti had for the first time acquired a measure of personal financial independence, thanks to a wealthy benefactress, American Mary Melissa Hoadley Dodge, who was domiciled in England.[33]

After the war, Krishnamurti embarked on a series of lectures, meetings and discussions around the world, related to his duties as the Head of the OSE, accompanied by Nitya, by then the Organizing Secretary of the Order.[34] Krishnamurti also continued writing.[35] The content of his talks and writings revolved around the work of the Order and of its members in preparation for the Coming. He was initially described as a halting, hesitant, and repetitive speaker, but his delivery and confidence improved, and he gradually took command of the meetings.[36]

In 1921 Krishnamurti fell in love with Helen Knothe, a 17-year-old American whose family associated with the Theosophists. The experience was tempered by the realisation that his work and expected life-mission precluded what would otherwise be considered normal relationships and by the mid-1920s the two of them had drifted apart.[37]

Life-altering experiencesIn 1922 Krishnamurti and Nitya travelled from Sydney to California. In California they stayed at a cottage in the Ojai Valley. It was thought that the area's climate would be beneficial to Nitya, who had been diagnosed with tuberculosis. Nitya's failing health became a concern for Krishnamurti.[38][39] At Ojai they met Rosalind Williams, a young American who became close to them both, and who was later to play a significant role in Krishnamurti's life.[40] For the first time the brothers were without immediate supervision by their Theosophical Society minders.[41] They found the Valley to be very agreeable. Eventually a trust, formed by supporters, bought a cottage and surrounding property there for them. This became Krishnamurti's official residence.[42]

At Ojai in August and September 1922 Krishnamurti went through an intense 'life-changing' experience.[43] This has been variously characterised as a spiritual awakening, a psychological transformation, and a physical reconditioning. The initial events happened in two distinct phases: first a three-day spiritual experience, and two weeks later, a longer-lasting condition that Krishnamurti and those around him referred to as the process. This condition recurred, at frequent intervals and with varying intensity, until his death.[44]

According to witnesses it started on 17 August 1922 when Krishnamurti complained of a sharp pain at the nape of his neck. Over the next two days the symptoms worsened, with increasing pain and sensitivity, loss of appetite, and occasional delirious ramblings. He seemed to lapse into unconsciousness, but later recounted that he was very much aware of his surroundings, and that while in that state he had an experience of "mystical union". The following day the symptoms and the experience intensified, climaxing with a sense of "immense peace".[45] Following — and apparently related to — these events[46] the condition that came to be known as the process started to affect him, in September and October that year, as a regular, almost nightly occurrence. Later the process resumed intermittently, with varying degrees of pain, physical discomfort and sensitivity, occasionally a lapse into a childlike state, and sometimes an apparent fading out of consciousness, explained as either his body giving in to pain or his mind "going off".[d]

These experiences were accompanied or followed by what was interchangeably described as, "the benediction," "the immensity," "the sacredness," "the vastness" and, most often, "the otherness" or "the other."[48] It was a state distinct from the process.[49] According to Lutyens it is evident from his notebook that this experience of otherness was "with him almost continuously" during his life, and gave him "a sense of being protected."[48] Krishnamurti describes it in his notebook as typically following an acute experience of the process, for example, on awakening the next day:

... woke up early with that strong feeling of otherness, of another world that is beyond all thought ... there is a heightening of sensitivity. Sensitivity, not only to beauty but also to all other things. The blade of grass was astonishingly green; that one blade of grass contained the whole spectrum of colour; it was intense, dazzling and such a small thing, so easy to destroy ...[50]

This experience of the otherness would be present with him in daily events:

It is strange how during one or two interviews that strength, that power filled the room. It seemed to be in one's eyes and breath. It comes into being, suddenly and most unexpectedly, with a force and intensity that is quite overpowering and at other times it's there, quietly and serenely. But it's there, whether one wants it or not. There is no possibility of getting used to it for it has never been nor will it ever be ..."[50]

Since the initial occurrences of 1922, several explanations have been proposed for this experience of Krishnamurti's.[e] Leadbeater and other Theosophists expected the "vehicle" to have certain paranormal experiences, but were nevertheless mystified by these developments.[51] During Krishnamurti's later years, the nature and provenance of the continuing process often came up as a subject in private discussions between himself and associates; these discussions shed some light on the subject, but were ultimately inconclusive.[52] Whatever the case, the process, and the inability of Leadbeater to explain it satisfactorily, if at all, had other consequences according to biographer Roland Vernon:

The process at Ojai, whatever its cause or validity, was a cataclysmic milestone for Krishna. Up until this time his spiritual progress, chequered though it might have been, had been planned with solemn deliberation by Theosophy's grandees. ... Something new had now occurred for which Krishna's training had not entirely prepared him. ... A burden was lifted from his conscience and he took his first step towards becoming an individual. ... In terms of his future role as a teacher, the process was his bedrock. ... It had come to him alone and had not been planted in him by his mentors ... it provided Krishna with the soil in which his newfound spirit of confidence and independence could take root.[53]

As news of these mystical experiences spread, rumours concerning the messianic status of Krishnamurti reached fever pitch as the 1925 Theosophical Society Convention was planned, on the 50th anniversary of its founding. There were expectations of significant happenings.[54] Paralleling the increasing adulation was Krishnamurti's growing discomfort with it. In related developments, prominent Theosophists and their factions within the Society were trying to position themselves favourably relative to the Coming, which was widely rumoured to be approaching. He stated that "Too much of everything is bad"."Extraordinary" pronouncements of spiritual advancement were made by various parties, disputed by others, and the internal Theosophical politics further alienated Krishnamurti.[55]

Nitya's persistent health problems had periodically resurfaced throughout this time. On 13 November 1925, at age 27, he died in Ojai from complications of influenza and tuberculosis.[56] Despite Nitya's poor health, his death was unexpected, and it fundamentally shook Krishnamurti's belief in Theosophy and in the leaders of the Theosophical Society. He had received their assurances regarding Nitya's health, and had come to believe that "Nitya was essential for [his] life-mission and therefore he would not be allowed to die," a belief shared by Annie Besant and Krishnamurti's circle.[57] Jayakar wrote that "his belief in the Masters and the hierarchy had undergone a total revolution."[58] Moreover, Nitya had been the "last surviving link to his family and childhood. ... The only person to whom he could talk openly, his best friend and companion."[59] According to eyewitness accounts, the news "broke him completely."[60] but 12 days after Nitya's death he was "immensely quiet, radiant, and free of all sentiment and emotion";[58] "there was not a shadow ... to show what he had been through."[61]

Break with the pastOver the next few years, Krishnamurti's new vision and consciousness continued to develop. New concepts appeared in his talks, discussions, and correspondence, together with an evolving vocabulary that was progressively free of Theosophical terminology.[62] His new direction reached a climax in 1929, when he rebuffed attempts by Leadbeater and Besant to continue with the Order of the Star.

Krishnamurti dissolved the Order during the annual Star Camp at Ommen, the Netherlands, on 3 August 1929.[63] He stated that he had made his decision after "careful consideration" during the previous two years, and that:

I maintain that truth is a pathless land, and you cannot approach it by any path whatsoever, by any religion, by any sect. That is my point of view, and I adhere to that absolutely and unconditionally. Truth, being limitless, unconditioned, unapproachable by any path whatsoever, cannot be organized; nor should any organization be formed to lead or coerce people along a particular path. ... This is no magnificent deed, because I do not want followers, and I mean this. The moment you follow someone you cease to follow Truth. I am not concerned whether you pay attention to what I say or not. I want to do a certain thing in the world and I am going to do it with unwavering concentration. I am concerning myself with only one essential thing: to set man free. I desire to free him from all cages, from all fears, and not to found religions, new sects, nor to establish new theories and new philosophies.[64]

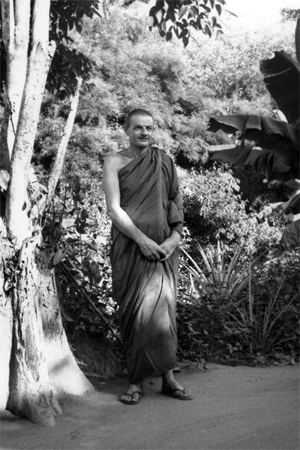

Krishnamurti in the early 1920s.

Krishnamurti in the early 1920s.Following the dissolution, prominent Theosophists turned against Krishnamurti, including Leadbeater who is said to have stated, "the Coming had gone wrong."[65] Krishnamurti had denounced all organised belief, the notion of gurus, and the whole teacher-follower relationship, vowing instead to work on setting people "absolutely, unconditionally free."[64] There is no record of his explicitly denying he was the World Teacher;[66] whenever he was asked to clarify his position he either asserted that the matter was irrelevant[67] or gave answers that, as he stated, were "purposely vague."[68]

In hind-sight it can be seen that the ongoing changes in his outlook had begun before the dissolution of the Order of the Star.[69] The subtlety of the new distinctions on the World Teacher issue was lost on many of his admirers, who were already bewildered or distraught because of the changes in Krishnamurti's outlook, vocabulary and pronouncements–among them Besant and Mary Lutyens' mother Emily, who had a very close relationship with him.[70][71] He soon disassociated himself from the Theosophical Society and its teachings and practices,[f] yet he remained on cordial terms with some of its members and ex-members throughout his life.[citation needed]

Krishnamurti would often refer to the totality of his work as the teachings and not as my teachings.[72]

Krishnamurti resigned from the various trusts and other organisations that were affiliated with the defunct Order of the Star, including the Theosophical Society. He returned the money and properties donated to the Order, among them a castle in the Netherlands and 5,000 acres (2,023 ha) of land, to their donors.[73]

Middle yearsFrom 1930 through 1944 Krishnamurti engaged in speaking tours and in the issue of publications under the auspice of the "Star Publishing Trust" (SPT), which he had founded with Desikacharya Rajagopal, a close associate and friend from the Order of the Star.[g] Ojai was the base of operations for the new enterprise, where Krishnamurti, Rajagopal, and Rosalind Williams (who had married Rajagopal in 1927) resided in the house known as Arya Vihara (meaning Realm of the Aryas i.e. those noble by righteousness in Sanskrit). The business and organizational aspects of the SPT were administered chiefly by D. Rajagopal, as Krishnamurti devoted his time to speaking and meditation. The Rajagopals' marriage was not a happy one, and the two became physically estranged after the 1931 birth of their daughter, Radha.[74] In the relative seclusion of Arya Vihara Krishnamurti's close friendship with Rosalind deepened into a love affair which was not made public until 1991. According to Radha Rajagopal Sloss, the long affair between Krishnamurti and Rosalind began in 1932 and it endured for about twenty-five years. [h][ i]

During the 1930s Krishnamurti spoke in Europe, Latin America, India, Australia and the United States. In 1938 he met Aldous Huxley.[75] The two began a close friendship which endured for many years. They held common concerns about the imminent conflict in Europe which they viewed as the outcome of the pernicious influence of nationalism.[76] Krishnamurti's stance on World War II was often construed as pacifism and even subversion during a time of patriotic fervor in the United States and for a time he came under the surveillance of the FBI.[77] He did not speak publicly for a period of about four years (between 1940 and 1944). During this time he lived and worked at Arya Vihara, which during the war operated as a largely self-sustaining farm, with its surplus goods donated for relief efforts in Europe.[78] Of the years spent in Ojai during the war he later said: "I think it was a period of no challenge, no demand, no outgoing. I think it was a kind of everything held in; and when I left Ojai it all burst."[79]

Krishnamurti broke the hiatus from public speaking in May 1944 with a series of talks in Ojai. These talks, and subsequent material, were published by "Krishnamurti Writings Inc" (KWINC), the successor organisation to the "Star Publishing Trust." This was to be the new central Krishnamurti-related entity worldwide, whose sole purpose was the dissemination of the teaching.[80] He had remained in contact with associates from India, and in the autumn of 1947 embarked on a speaking tour there, attracting a new following of young intellectuals.[j] On this trip he encountered the Mehta sisters, Pupul and Nandini, who became lifelong associates and confidants. The sisters also attended to Krishnamurti throughout a 1948 recurrence of the "process" in Ootacamund.[81] In Poona in 1948, Krishnamurti met Iyengar, who taught him Yoga practices every morning for the next three months, then on and off for twenty years.[82]

When Krishnamurti was in India after World War II many prominent personalities came to meet him, including Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru. In his meetings with Nehru Krishnamurti elaborated at length on the teachings, saying in one instance, "Understanding of the self only arises in relationship, in watching yourself in relationship to people, ideas, and things; to trees, the earth, and the world around you and within you. Relationship is the mirror in which the self is revealed. Without self-knowledge there is no basis for right thought and action." Nehru asked, "How does one start?" to which Krishnamurti replied, "Begin where you are. Read every word, every phrase, every paragraph of the mind, as it operates through thought."[83]

Later yearsKrishnamurti continued speaking in public lectures, group discussions and with concerned individuals around the world. In the early 1960s, he made the acquaintance of physicist David Bohm, whose philosophical and scientific concerns regarding the essence of the physical world, and the psychological and sociological state of mankind, found parallels in Krishnamurti's philosophy. The two men soon became close friends and started a common inquiry, in the form of personal dialogues–and occasionally in group discussions with other participants–that continued, periodically, over nearly two decades.[k] Several of these discussions were published in the form of books or as parts of books, and introduced a wider audience (among scientists) to Krishnamurti's ideas.[84] Although Krishnamurti's philosophy delved into fields as diverse as religious studies, education, psychology, physics, and consciousness studies, he was not then, nor since, well known in academic circles. Nevertheless, Krishnamurti met and held discussions with physicists Fritjof Capra and E. C. George Sudarshan, biologist Rupert Sheldrake, psychiatrist David Shainberg, as well as psychotherapists representing various theoretical orientations.[85] The long friendship with Bohm went through a rocky interval in later years, and although they overcame their differences and remained friends until Krishnamurti's death, the relationship did not regain its previous intensity.[citation needed][l][m]

In the 1970s, Krishnamurti met several times with then Indian prime minister Indira Gandhi, with whom he had far ranging, and in some cases, very serious discussions. Jayakar considers his message in meetings with Indira Gandhi as a possible influence in the lifting of certain emergency measures Gandhi had imposed during periods of political turmoil.[86]

Meanwhile, Krishnamurti's once close relationship with the Rajagopals had deteriorated to the point where he took D. Rajagopal to court to recover donated property and funds as well as publication rights for his works, manuscripts, and personal correspondence, that were in Rajagopal's possession.[n] The litigation and ensuing cross complaints, which formally began in 1971, continued for many years. Much property and materials were returned to Krishnamurti during his lifetime; the parties to this case finally settled all other matters in 1986, shortly after his death.[o]

In 1984 and 1985, Krishnamurti spoke to an invited audience at the United Nations in New York, under the auspices of the Pacem in Terris Society chapter at the United Nations.[87] In October 1985, he visited India for the last time, holding a number of what came to be known as "farewell" talks and discussions between then and January 1986. These last talks included the fundamental questions he had been asking through the years, as well as newer concerns about advances in science and technology, and their effect on humankind. Krishnamurti had commented to friends that he did not wish to invite death, but was not sure how long his body would last (he had already lost considerable weight), and once he could no longer talk, he would have "no further purpose". In his final talk, on 4 January 1986, in Madras, he again invited the audience to examine with him the nature of inquiry, the effect of technology, the nature of life and meditation, and the nature of creation.[citation needed]

Krishnamurti was also concerned about his legacy, about being unwittingly turned into some personage whose teachings had been handed down to special individuals, rather than the world at large. He did not want anybody to pose as an interpreter of the teaching.[88] He warned his associates on several occasions that they were not to present themselves as spokesmen on his behalf, or as his successors after his death.[89]

A few days before his death, in a final statement, he declared that nobody among either his associates or the general public had understood what had happened to him (as the conduit of the teaching). He added that the "supreme intelligence" operating in his body would be gone with his death, again implying the impossibility of successors. However, he stated that people could perhaps get into touch with that somewhat "if they live the teachings".[90] In prior discussions, he had compared himself with Thomas Edison, implying that he did the hard work, and now all that was needed by others was a flick of the switch.[91]

DeathKrishnamurti died of pancreatic cancer on 17 February 1986, at the age of 90. His remains were cremated. The announcement of KFT (Krishnamurti Foundation Trust) refers to the course of his health condition until the moment of death. The first signs came almost nine months before his death, when he felt very tired. In October 1985 he went from England (Brockwood Park School) to India and after that he suffered from exhaustion, fevers, and lost weight. Krishnamurti decided to go back to Ojai (10 January 1986) after his last talks in Madras, which necessitated a 24-hour flight. Once he arrived at Ojai he underwent medical tests that revealed he was suffering from pancreatic cancer. The cancer was untreatable, either surgically or otherwise, so Krishnamurti decided to go back to his home at Ojai, where he spent his last days. Friends and professionals nursed him. His mind was clear until the very last. Krishnamurti died on 17 February 1986, at ten minutes past midnight, California time.

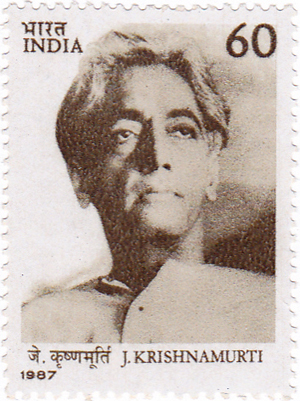

Schools Krishnamurti on a 1987 stamp of India

Krishnamurti on a 1987 stamp of IndiaKrishnamurti founded several schools around the world, including Brockwood Park School, an international educational center. When asked, he enumerated the following as his educational aims:

1. Global outlook: A vision of the whole as distinct from the part; there should never be a sectarian outlook, but always a holistic outlook free from all prejudice.

2. Concern for man and the environment: Humanity is part of nature, and if nature is not cared for, it will boomerang on man. Only the right education, and deep affection between people everywhere, will resolve many problems including the environmental challenges.

3. Religious spirit, which includes the scientific temper: The religious mind is alone, not lonely. It is in communion with people and nature.[92]

The Krishnamurti Foundation, established in 1928 by him and Annie Besant, runs many schools in India and abroad.[93]

InfluenceKrishnamurti attracted the interest of the mainstream religious establishment in India. He engaged in discussions with several well known Hindu and Buddhist scholars and leaders, including the Dalai Lama.[p] Several of these discussions were later published as chapters in various Krishnamurti books. Those influenced by Krishnamurti include Toni Packer,[citation needed] Achyut Patwardhan,[94] and Dada Dharmadhikari.[95]

Interest in Krishnamurti and his work has persisted in the years since his death. Many books, audio, video, and computer materials, remain in print and are carried by major online and traditional retailers. The four official Foundations continue to maintain archives, disseminate the teachings in an increasing number of languages, convert print to digital and other media, develop websites, sponsor television programs, and organise meetings and dialogues of interested persons around the world.[96]

WorksMain article: Jiddu Krishnamurti bibliography

See also: List of works about Jiddu Krishnamurti

• At the Feet of the Master (1910)

• The First and Last Freedom (1954)

• Commentaries on Living (1956–1960)

• Freedom from the Known (1969)

• Krishnamurti's Notebook (1976)

• Krishnamurti's Journal (1982)

• Krishnamurti to Himself (1987)

References

Notes1. According to occult and Theosophical lore, auras are invisible emanations related to each individual's so-called subtler planes of existence, as well as her or his normal plane. The ability to discern a person's aura is considered one of the possible effects of clairvoyance. Leadbeater's occult knowledge and abilities were highly respected within the Society.[14]

2. Lutyens (1975), pp. 40–63 [cumulative]. The news regarding Krishnamurti and the World Teacher were not universally welcomed by Theosophists and led to upheavals in the Society; Lutyens (1983a), pp. 15–19, 40, 56. Part of the controversy was Leadbeater's role. He had a history of being in the company of young boys–pupils under his spiritual and Theosophical instruction, and there was gossip about child abuse — although no accusations were ever proven.

3. Lutyens (1975), "Chapter 10: Doubts and Difficulties" through "Chapter 15: In Love" pp. 80–132 [cumulative].

4. Lutyens (1975), "Chapter 18: The Turning Point" through "Chapter 21: Climax of the Process" pp. 152–188 [cumulative]. The use of the term "going off" in the accounts of the early occurrences of the process apparently signified so-called out-of-body experiences.[47] In later usage the meaning of "going off" was more nuanced.

5. Jayakar (1986), p. 46n. and Lutyens (1975), p. 166 provide a frequently given explanation, that it represented the so-called awakening of kundalini, a process that according to Hindu mysticism culminates in transcendent consciousness. Others view it in Freudian terms. Aberbach (1993) contends that the experiences were a projection of Krishnamurti's accumulated grief over the death of his mother. Sloss (1993), p. 61 considers the process to be a purely physical event centred on sickness or trauma, and suggest the possibility of epilepsy, a possibility that Lutyens (1990) rejects. According to Lutyens (1990), pp. 45–46., Krishnamurti believed the process was necessary for his spiritual development and not a medical matter or condition. As far as he was concerned, he had encountered Truth; he thought the process was in some way related to this encounter, and to later experiences.

6. Lutyens considers the last remaining tie with Theosophy to have been severed in 1933, with the death of Besant. He had resigned from the Society in 1930 (Lutyens, 1975; pp. 276, 285).

7. Born in India in 1900 and of Brahmin descent, Rajagopal had moved in Krishnamurti's circle since early youth. Although regarded as an excellent editor and organizer, he was also known for his difficult personality and high-handed manner. Upon Nitya's death, he had promised Besant that he would look after Krishnamurti. See Henri Methorst, Krishnamurti A Spiritual Revolutionary, Edwin Publishing House, 2003, ch 12.

8. The two also shared an interest in education: Krishnamurti helped to raise Radha, and the need to provide her with a suitable educational environment led to the founding of the Happy Valley School in 1946. The school has since re-established itself as an independent institution operating as the Besant Hill School Of Happy Valley. See Sloss, "Lives in the Shadow," ch 19.

9. Radha's account of the relationship, Lives in the Shadow With J. Krishnamurti, was first published in England by Bloomsbury Publishing Ltd. in 1991, and was soon followed by a rebuttal volume written by Mary Lutyens, Krishnamurti and the Rajagopals, Krishnamurti Foundation of America, 1996, in which she acknowledges the relationship.

10. These included former freedom campaigners from the Indian Independence Movement, See Vernon, "Star in the East," p 219.

11. Bohm would eventually serve as a Krishnamurti Foundationtrustee.

12. Their falling out was partly due to questions about Krishnamurti's private behaviour, especially his long and secret love affair with Rosalind Williams-Rajagopal, then unknown to the general public.[citation needed]

13. After their falling out, Bohm criticised certain aspects of the teaching on philosophical, methodological, and psychological grounds. He also criticised what he described as Krishnamurti's occasional "verbal manipulations" when deflecting challenges. Eventually, he questioned some of the reasoning about the nature of thought and self, although he never abandoned his belief that "Krishnamurti was onto something". See Infinite Potential: The Life and times of David Bohm, by F. David Peat, Addison Wesley, 1997.

14. D. Rajagopal was the head or co-head of a number of successive corporations and trusts, set up after the dissolution of the Order of the Star and chartered to publish Krishnamurti's talks, discussions and other writings.

15. Formation of the Krishnamurti Foundation of America and the Lawsuits Which Took Place Between 1968 and 1986 to Recover Assets for Krishnamurti's Work, by Erna Lilliefelt, Krishnamurti Foundation of America, 1995. The complicated settlement dissolved the K & R Foundation (a previous entity), and transferred assets to the Krishnamurti Foundation of America(KFA). However certain disputed documents remained in the possession of Rajagopal, and he received partial repayment for his attorney's fees.

16. The Dalai Lama characterised Krishnamurti as a "great soul"(Jayakar, "Krishnamurti" p 203). Krishnamurti very much enjoyed the Lama's company and by his own admission could not bring up his anti-guru views, mindful of the Lama's feelings.

Citations1. "Jiddu Krishnamurti". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

2. Mind is a Myth

3. Lutyens (1995), footnotes 1, 2.

4. Williams (2004), p. 465.

5. Lutyens (1975). p. 7.

6. Lutyens (1975). p. 5.

7. Williams (2004), pp. 471–472.

8. Lutyens (1975), pp.2–4.

9. Lutyens (1975), pp. 3–4, 22, 25.

10. Lutyens (1983a), pp. 5, 309

11. J. Krishnamurti (2004), p. 16.

12. Lutyens (1983a), pp. 7–8.

13. Star In The East: The Invention of A Messiah, by Roland Vernon, Palgrave 2001, p 41.

14. Lutyens (1975), pp. 15, 20–21

15. Jump up to:a b Lutyens (1975), p. 21.

16. Pupul (1986), p. 28.

17. Jayakar (1986), p. xi. The suffix –ji in Hindu names is a sign of affection or respect.

18. Vernon (2001), pp. 51–72.

19. Lutyens (1995)

20. Lutyens (1975), p. 40.

21. Lutyens (1975), pp. 54–63, 64–71, 82, 84.

22. Lutyens (1975), pp. 3, 32.

23. Lutyens (1975), p. 10-11, 93.

24. Vernon (2001), p. 57.

25. Lutyens (1975), "Chapter 4: First Initiation" and "Chapter 5: First Teaching" pp. 29–46 [cumulative].

26. Lutyens (1997), pp. 83, 120, 149.

27. Jump up to:a b Vernon (2001), p. 53.

28. Vernon (2001), p. 52.

29. Lutyens (1975), pp. 50–51.

30. Lutyens (1975), pp. 51–52.

31. Lutyens (1997), pp. 46, 74–75, 126. Krishnamurti was named Editor of the Herald of the Star, the official bulletin of the OSE. His position was mainly as a figurehead, yet he often wrote editorial notes, which along with his other contributions helped the magazine's circulation.

32. Vernon (2001), p. 65.

33. Lutyens (1975), pp. 4, 75, 77.

34. Lutyens (1975), p. 125.

35. See Jiddu Krishnamurti bibliography.

36. Lutyens (1975), pp. 134–35, 171–17.

37. Lutyens (1975), pp. 114, 118, 131–132, 258.

38. Vernon (2001), p. 97.

39. Lutyens (1975), pp. 149, 199, 209, 216–217.

40. Lutyens (1991), p. 35.

41. Vernon (2001), p. 113.

42. Lutyens (1983b), p. 6.

43. Jayakar (1986), pp. 46–57.

44. Vernon (2001), p. 282.

45. Lutyens (1975), pp. 158–160.

46. Lutyens (1975), p. 165.

47. Lutyens (1990), pp. 134–135.

48. Jump up to:a b Lutyens, M. (1988). J. Krishnamurti: The Open Door.Volume 3 of Biography, p. 12. ISBN 0-900506-21-0. Retrieved on: 19 November 2011.

49. "J. Krishnamurti, Krishnamurti's Notebook, Foreword by Mary Lutyens". jkrishnamurti.org. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

50. Jump up to:a b Krishnamurti, J. (1976). Krishnamurti's Notebook, Part 3 Gstaad, Switzerland 13th July to 3rd September 1961. J. Krishnamurti online. ISBN 1-888004-63-0, ISBN 978-1-888004-63-2.

51. Lutyens (1975), pp. 163–4, 188–9.

52. Jayakar (1986), p. 133.

53. Vernon (2001), pp. 131–132.

54. Lutyens (1975), p. 223.

55. Lutyens (1990), pp. 57–60.

56. Lutyens (1975), p. 219.

57. Lutyens (1975), pp. 219, 221.

58. Jump up to:a b Jayakar (1986), p. 69.

59. Vernon (2001), p. 152.

60. Lutyens (1975), pp. 220, 313 (note to p. 220).

61. Lutyens (1975), p. 221.

62. Lutyens (1983c), p. 234.

63. Lutyens (1975), p. 272.

64. Jump up to:a b J. Krishnamurti (1929).

65. Lutyens (1997), pp. 277–279.

66. Vernon (2001), pp. 166–167.

67. J. Krishnamurti (1972), p. 9. "I think we shall have incessant wrangles over the corpse of Krishnamurti if we discuss this or that, wondering who is now speaking. Someone asked me: 'Do tell me if it is you speaking or someone else'. I said: 'I really do not know and it does not matter'." From the 1927 "Question and answer session" at Ommen. [Note weblink in reference is not at official Krishnamurti-related or Theosophical Society website].

68. J. Krishnamurti (1928a), p. 43. "I am going to be purposely vague, because although I could quite easily make it definite, it is not my intention to do so. Because once you define a thing it becomes dead." Krishnamurti on the World Teacher, from "Who brings the truth," an address delivered at Ommen 2 August 1927. Note weblink in reference is not at official Krishnamurti-related or Theosophical Society website. Link-specific content verified against original at New York Public Library Main Branch, "YAM p.v. 519" [call no..

69. Lutyens (1975), p. 262.

70. Vernon (2001), p. 189.

71. Lutyens (1975), p. 236.

72. Lutyens (1990), p. 210. Emphasis in source.

73. Lutyens (1975), pp. 276–284.

74. Lives in the Shadow with J. Krishnamurti by Radha Rajagopal Sloss, Bloomsbury Publishing, 1991, ch 12.

75. Vernon, "Star in the East," p 205.

76. "Journal of the Krishnamurti Schools". Retrieved 4 June2018.

77. Vernon, "Star in the East," p 209.

78. Vernon, "Star in the East," p 210.

79. Jayakar, "Krishnamurti" p 98.

80. Lutyens, "Fulfillment," Farrar, Straus hardcover, p 59-60. Initially, Krishnamurti (along with Rajagopal and others) was a trustee of KWINC. Eventually he ceased being a trustee, leaving Rajagopal as President–a turn of events that according to Lutyens, constituted "... a circumstance that was to have most unhappy consequences."

81. See Jayakar, "Krishnamurti," ch 11 for Pupul Mehta's (later Jayakar) eyewitness account.

82. Elliot Goldberg, The Path of Modern Yoga (Rochester VT: Inner Traditions 2016), p. 380.

83. Jayakar, "Krishnamurti," p 142.

84. See Selected Publications/List of Books subsection.

85. See On Krishnamurti, by Raymond Martin, Wadsworth, 2003, for a discussion on Krishnamurti and the academic world.

86. See Jayakar, "Krishnamurti" pages 340–343.

87. Lutyens, "The Open Door," p 84-85. Also Lutyens, "The Life and Death of Krishnamurti," p. 185.

88. Lutyens, "Fulfilment," Farrar, Straus hardcover, p 171, statement of Krishnamurti published in the Foundation Bulletin, 1970.

89. Lutyens, "Fulfilment," Farrar, Straus hardcover, p 233.

90. See Lutyens, "The Life and Death of Krishnamurti," London: John Murray, p 206. Quoting Krishnamurti from tape-recording made on 7 February 1986.

91. Lutyens, "Fulfilment" Farrar, Straus hardcover, p 119.

92. See As The River Joins The Ocean: Reflections about J. Krishnamurti, by Giddu Narayan, Edwin House Publishing 1999, p 64.

93. Evangelos Grammenos. Krishnamurti and the Fourth Way. p. 200. ISBN 9788178990057.

94. "Obituary: Achyut Patwardhan". The Independent. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

95. "Dada Dharmadhikari Biography". mkgandhi-sarvodaya.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

96. See also The Complete Teachings Project Archived 2 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, an ambitious effort to collect the entire body of Krishnamurti's work into a coherently edited master reference.

Bibliography• Aberbach, David (1 July 1993). "Mystical Union and Grief: the Ba'al Shem Tov and Krishnamurti". Harvard Theological Review. Cambridge, Massachusetts. 86 (3): 309–321. doi:10.1017/s0017816000031254. ISSN 0017-8160. JSTOR 1510013.(subscription required)

• Jayakar, Pupul (1986). Krishnamurti: a biography (1st ed.). San Francisco: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-250401-2.

• Jiddu, Krishnamurti (1 January 1926). "Editorial Notes". The Herald of the Star. London: Theosophical Publishing House. XV (1): 3. OCLC 225662044.

• Jiddu, Krishnamurti (1928a). "Who brings the truth?". The pool of wisdom, Who brings the truth, By what authority, and three poems. Eerde, Ommen: Star Publishing Trust. pp. 43–53. OCLC 4894479. Saaremaa, Estonia: jiddu-krishnamurti.net [web publisher]. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

• Jiddu, Krishnamurti (September 1929). "The dissolution of the Order of the Star: a statement by J. Krishnamurti". International Star Bulletin. Eerde, Ommen: Star Publishing Trust. 3 (2 [issues renumbered starting August 1929]): 28–34. OCLC 34693176. J.Krishnamurti Online [web publisher]. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

• Jiddu, Krishnamurti (1 August 1965). "Tenth public talk at Saanen". J.Krishnamurti Online. Krishnamurti Foundations. JKO 650801. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

• Jiddu, Krishnamurti (1972). "Eerde Gathering 1927, Questions and Answers". Early Writings of J. Krishnamurti. Early Writings. II [Offprints from Chetana 1970]. Bombay: Chetana. pp. 6–14. OCLC 312923125. Saaremaa, Estonia: jiddu-krishnamurti.net [web publisher]. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

• Jiddu, Krishnamurti (1975b) [1969]. Lutyens, Mary (ed.). Freedom from the Known (reprint, 1st Harper paperback ed.). San Francisco: Harper San Francisco. ISBN 978-0-06-064808-4. JKO 237.

• Jiddu, Krishnamurti (2004) [originally published 1982. San Francisco: Harper & Row]. Krishnamurti's Journal. Bramdean: Krishnamurti Foundation Trust. ISBN 978-0-900506-23-9.

• Lutyens, Mary (1975). Krishnamurti: The Years of Awakening (1st US ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-18222-9.

• Lutyens, Mary (1983b). Krishnamurti: The Years of Fulfilment (1st US ed.). New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-0-374-18224-3.

• Lutyens, Mary (1990). The life and death of Krishnamurti (1st UK ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-4749-2.

• Lutyens, Mary (1995). The boy Krishna: the first fourteen years in the life of J. Krishnamurti (pamphlet). Bramdean: Krishnamurti Foundation Trust. ISBN 978-0-900506-13-0.

• Sloss, Radha Rajagopal (1991). Lives in the Shadow with J. Krishnamurti (1st ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-0720-8.

• Vernon, Roland (2001). Star in the east: Krishnamurti: the invention of a messiah. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-23825-4.

• Williams, Christine V. (2004). Jiddu Krishnamurti: world philosopher (1895–1986): his life and thoughts. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2032-6. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

External links• Works by Jiddu Krishnamurti at Project Gutenberg

• J. Krishnamurti Online Official website — making available thousands of transcripts as well as many audio and video recordings. An international joint venture of the four Krishnamurti Foundations.

• Krishnamurti Foundation Trust – Established in 1968 as an educational charitable trust, the Foundation exists to preserve and make available the teachings of J. Krishnamurti.

• Krishnamurti and the Ojai Valley

• The Bohm-Krishnamurti Project: Exploring the Legacy of the David Bohm and Jiddu Krishnamurti Relationship

• The Krishnamurti Study Centre A retreat centre in England

• J Krishnamurti Study Centre in Hyderabad, India

• The Levin Interviews - Bernard Levin's interviews with Jiddu Krishnamurti

• Newspaper clippings about Jiddu Krishnamurti in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW