Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

Harry Johnston

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/3/20

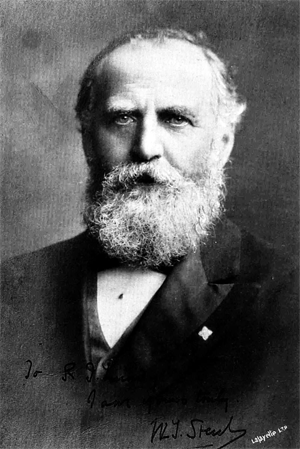

Harry Johnston, by Elliott & Fry.

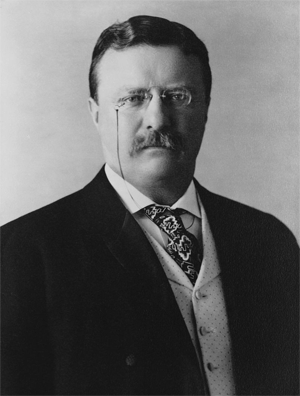

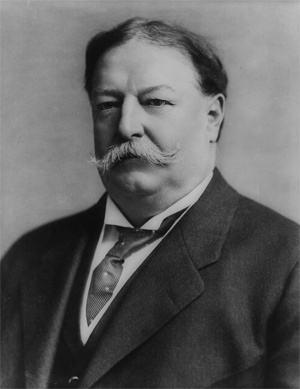

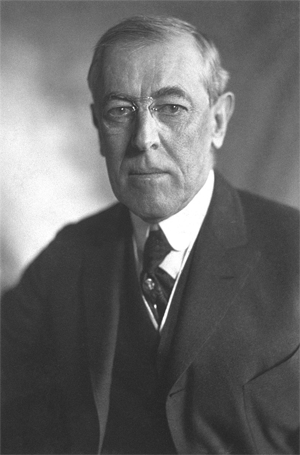

Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston GCMG KCB (12 June 1858 – 31 July 1927), frequently known as Harry Johnston, was a British explorer, botanist, artist, colonial administrator and linguist who traveled widely in Africa and spoke many African languages. He published 40 books on African subjects and was one of the key players in the Scramble for Africa that occurred at the end of the 19th century.

Early years

Born at Kennington Park, south London, the son of John Brookes Johnstone and Esther Laetitia Hamilton. He attended Stockwell grammar school and then King's College London, followed by four years studying painting at the Royal Academy. In connection with his study he travelled to Europe and North Africa, visiting the little-known (by Europeans) interior of Tunisia.[1]

Exploration in Africa

In 1882 he visited southern Angola with the Earl of Mayo, and in the following year met Henry Morton Stanley in the Congo, becoming one of the first Europeans after Stanley to see the river above the Stanley Pool. His developing reputation led the Royal Geographical Society and the British Association to appoint him leader of an 1884 scientific expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro. On this expedition he concluded treaties with local chiefs (which were then transferred to the British East Africa Company), in competition with German efforts to do likewise.[2]

British colonial service and the Cape to Cairo vision

In October 1886 the British government appointed him vice-consul in Cameroon and the Niger River delta area, where a protectorate had been declared in 1885, and he became acting consul in 1887,[3] deposing and banishing the local chief Jaja.

While in West Africa in 1886, Johnston sketched what has been termed a "fantasy map" of his ideas of how the African continent could be divided among the colonial powers. This envisaged two blocks of British colonies, one of continuous territory in West Africa, the Nile valley and much of East Africa as far south as Lake Tanganyika and Lake Nyasa, the other in southern Africa south of the Zambezi. This left a continuous band in Portuguese occupation from Angola to Mozambique and Germany in possession of much of the East African coast.[4]

The original proposal for a Cape to Cairo railway was made in 1874 by Edwin Arnold, the then editor of the Daily Telegraph, which was joint sponsor of the expedition by H.M. Stanley to Africa to discover the course of the Congo River.[5] The proposed route involved a mixture of railway and river transport between Elizabethville, now Lubumbashi in the Belgian Congo and Sennar in the Sudan rather than a completely rail one.[6] Johnston later acknowledged his debt to Stanley and Arnold and when on leave in England in 1888, he revived the Cape-to-Cairo concept of acquiring a continuous band of British territory down Africa in discussion with Lord Salisbury. Johnston then published an supporting the idea article in Times anonymously, as "by an African Explorer" and later in 1888 and 1889 published a number of articles in other newspapers and journals with Salisbury's tacit approval.[7]

Scramble for Katanga

The Berlin Conference had allocated Katanga to the sphere of influence of King Leopold of Belgium's Congo Free State, but under the Berlin Conference's Principle of Effectivity this was only provisional. In July 1890, Leopold protested to Lord Salisbury that Johnston, as agent for Cecil Rhodes, was circulating maps showing that the Congo Free State did not include Katanga, and in response to Salisbury's enquiries, in August 1890 Johnston presented Rhodes' claim, which included the false information that Msiri, King of Garanganze in Katanga had asked for British protection.[8]

In November 1890, to justify his claim, Johnston sent Alfred Sharpe (who would become his successor in Nyasaland) to act for Rhodes and the British South Africa Company (BSAC), to obtain a treaty with Msiri, a move which had the potential to precipitate an Anglo-Belgian crisis. Sharpe failed with Msiri, though he obtained treaties with Mwata Kazembe covering the eastern side of the Luapula River and Lake Mweru, and with other chiefs covering the southern end of Lake Tanganyika. When Leopold again protested to Salisbury in May 1891, the latter had to admit Msiri had not signed a treaty asking for British protection and left Katanga open to Belgian colonisation. In 1891 Leopold sent the Stairs Expedition to Katanga. Johnston dissuaded it from accessing Katanga through Nyasaland, but it went through German East Africa instead, and took Katanga after killing Msiri. The southern border of the Congo Free State was settled by an Anglo-Congo agreement of 1894.[9]

Nyasaland (British Central Africa Protectorate)

Portrait of Johnston by Theodore Blake Wirgman (1894)

In 1879 the Portuguese government formally claimed the area south and east of the Ruo River (currently the southeastern border of Malawi) and then, in 1882, occupied the lower Shire River valley as far north as the Ruo. It attempted to gain British acceptance of this claim without success, and also failed in a claim that the Shire Highlands was part of Portuguese East Africa, as it was not under effective occupation[10] As late as 1888, the British Foreign Office would not accept responsibility for British missionaries and settlers in the Shire Highlands after the African Lakes Corporation had tried but failed to become a Chartered company with interests there and around the western shore of Lake Malawi.[11]

However, in 1885–86 Alexandre de Serpa Pinto had undertaken an expedition which reached Shire Highlands, which had failed make any treaties of protection with the Yao chiefs west of Lake Malawi.[12] To prevent possible Portuguese occupation, in November 1888, Johnston was appointed as Commissioner and Consul-general for the Mozambique and the Nyasa districts, and arrived in Blantyre in March 1889.[13] On his way to take up his appointment, Johnston spent six weeks in Lisbon attempting to negotiate an acceptable agreement on Portuguese and British spheres of influence in southeastern Africa. However, as the draft agreement did not expressly exclude the Shire Highlands from the Portuguese sphere, it was rejected by the Foreign Office.[14]

Among several pressing problems was the Karonga War, a dispute between and Swahili traders in slaves and ivory and their Henga allies on one side and the African Lakes Trading Company and elements of the Ngonde people on the other which had broken out in 1887[15]. As Johnston had no significant forces at that time, he agreed a truce with the Swahili leaders in October 1889[16]but the Swahili traders did not adhere to its terms.[17]

In late 1888 and early 1889, the Portuguese government sent two expeditions to make treaties of protection with local chiefs, one under Antonio Cardoso set off toward Lake Malawi, the other under Alexandre de Serpa Pinto moved up the Shire valley. Between them, they made over twenty treaties with chiefs in what is now Malawi[18] Johnston met Serpa Pinto in August 1889 east of the Ruo and advised him not to cross the river, but Serpa Pinto disregarded this and crossed the river to Chiromo, now in Malawi.[19] In September, following minor clashes between Serpa Pinto's force and local Africans, Johnston's deputy declared a Shire Highlands Protectorate, despite the contrary instructions.[20] Johnston's proclamation of a further protectorate, the Nyasaland Districts Protectorate, west of Lake Malawi was endorsed by the Foreign Office in May 1891.[21]

Johnston arrived in Chiromo, in the south of Nyasaland, on 16 July 1891.[22] By that time he had already selected a team of men who were to assist in forming the administration of the new protectorate. They included Alfred Sharpe (Johnston's Deputy Commissioner), Bertram L. Sclater (Surveyor, Roadmaker, and Commandant of the Constabulary), Alexander Whyte (a zoologist who was to discover several new species in Nyasaland), Cecil Montgomery Maguire (Military Commandant), Hugh Charlie Marshall (Customs Officer, Collector of Revenues and Postmaster for the Chiromo district), John Buchanan (an agriculturalist who had been in Nyasaland since 1876, and was appointed Vice Consul by Johnston), and others.

In 1891, Johnston only controlled a fraction of the Shire Highlands, itself a small part of the whole protectorate. He was provided with a small force of Indian troops in 1891, and began to train African soldiers and police. At first, Johnston used his small force in the south of the protectorate to suppress slave trading by Yao chiefs, who had established links with Swahili traders in ivory and slaves from the early 19th century. As the Yao people had no central authority, Johnston was able to defeat one group at a time, although this took until 1894, as he left the most powerful chief, Makanjira, until almost last, starting an amphibious operation against him in late 1893.[23]

Before the British Central Africa Protectorate was proclaimed in May 1891, a number of European companies and settlers had made, or claimed to have made, treaties with local chiefs under which the land owned by the African communities that occupied it was transferred to the Europeans in exchange for protection and some trade goods.[24] The African Lakes Company claimed over 2.75 million acres in the north of the protectorate, some under treaties that claimed to transfer sovereignty to the company[25], and three others individuals claimed to have purchased large areas of land in the south. Eugene Sharrer claimed 363,034 acres, Alexander Low Bruce claimed 176,000 acres, and John Buchanan and his brothers claimed a further 167,823 acres. These lands were purchased for trivial quantities of goods under agreements signed by chiefs with no understanding of English concepts of land tenure.[26][27]

Johnston had the task of reviewing these land claims, and began to do so in late 1892, as the proclamation of the protectorate had been followed by a wholesale land grab, with huge areas of land bought for trivial sums and some claims overlapping. He rejected any suggestion that treaties made before the protectorate was established could transfer sovereignty to individuals or companies, but accept that they could be evidence of land sales. Although Johnston accepted that the land belonged to its African communities, so their chiefs had no right to alienate it, he suggested that each community had given their chief this right. Despite having no legal training, he claimed that, as Commissioner, he was entitled to investigate these land sales and to issue Certificates of Claim registering freehold title to the European claimants. He rejected very few claims, despite the questionable evidence for several major ones. The existing African villages and farms were exempted from these sales, and the villagers were told that their homes and fields were not being alienated. Despite this, the concentration of much of the most fertile land in the Shire Highlands in the hands of European owners had profound economic consequences that lasted throughout the colonial period.[28][29]

In April 1894 Johnston returned to England and was away for a year. He had quarrelled with Cecil Rhodes who had so far provided most of his funds, and during the first three years the administration had run up a deficit of £20,000. During his leave he managed to persuade the British Government to agree to take over the financing of the country. On his way back he visited Egypt and India with a view to recruiting soldiers, and eventually arrived back in Nyasaland with a flotilla of boats, 202 Sikh soldiers, and over 400 other men. 4000 porters were recruited in the Shire Highlands to carry stores and equipment. Johnston reached Zomba on 3 May 1895.[30]

Johnston visited Karonga in June 1895 to try to make a settlement but the Swahili leaders refused either to meet him curtail their raiding activities, so Johnston decided on military action.[31] In November 1895, Johnston he embarked a force of over 400 Sikh and African riflemen, with artillery and machine guns on steamers to Karonga and surrounded the traders' main stockaded town, bombarding it for two days and finally assaulting it on 4 December. The Swahili leader, Mlozi was captured, given a cursory trial and hanged on 5 December and between 200 and 300 of fighters and several hundred non-combatants were killed, many while attempting to surrender. Other Swahili stockades did not resist and were destroyed.[32]

North-Eastern Rhodesia and Nyasaland

Johnston realised the strategic importance of Lake Tanganyika to the British, especially since the territory between the lake and the coast had become German East Africa forming a break of nearly 900 km in the chain of British colonies in the Cape to Cairo dream. However the north end of Lake Tanganyika was only 230 km from British-controlled Uganda, and so a British presence at the south end of the lake was a priority. Although the northern boundaries of North-Eastern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were eventually settled by negotiations between Britain, Germany. Portugal and the Congo Free State, Johnston ensured that British bomas were established (in addition to those in Nyasaland) east of Luapula-Mweru at Chiengi and the Kalungwishi River, at the south end of Lake Tanganyika at Abercorn, and at Fort Jameson between Mozambique and the Luangwa valley to demonstrate effective occupation.[33]

Until 1899, Johnson had administrative control the territory which became North-Eastern Rhodesia (the north-eastern half of today's Zambia), and he helped to set up and oversee the British South Africa Company's administration in that area. North-Eastern Rhodesia was little developed in this period, being regarded principally as a labour reserve, with only a handful of company administrators.[34]

Although he missed out in Katanga, altogether he helped to consolidate an area of nearly half a million square kilometres into the British Empire – nearly 200,000 square miles (520,000 km2), or twice the area of the United Kingdom in 2009 – lying between the lower Luangwa River valley and lakes Nyasa, Tanganyika, and Mweru.

Later years

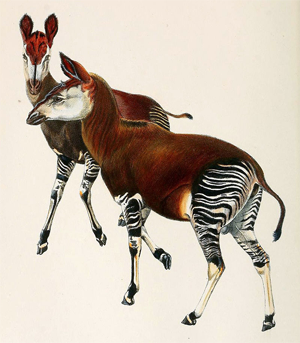

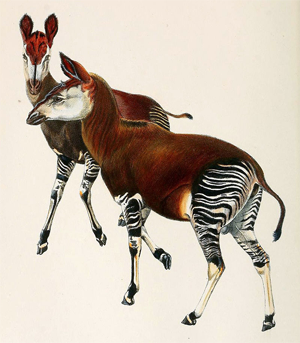

Okapi, from an original painting by Johnston, based on preserved skins (1901)

In 1896 in recognition of this achievement he was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB), but afflicted by tropical fevers, transferred to Tunis as consul-general. In the same year, he had married the Hon. Winifred Mary Irby, daughter of Florance George Henry Irby, fifth Baron Boston.[35]

In 1899 Sir Harry was sent to Uganda as special commissioner to end an ongoing war. He improved the colonial administration, and concluded the Buganda Agreement of 1900, dividing the land between the UK and the chiefs. For his services in Uganda, he received the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) in the King's Birthday Honours list in November 1901.[36] Also in 1901, Johnston was the first recipient of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society's Livingstone Medal,[37] and in the following year he was appointed a member of the council of the Zoological Society of London.[38] He received the honorary degree Doctor of Science (D.Sc.) from the University of Cambridge in May 1902.[39] The Royal Geographical Society awarded him their 1904 Founder's Gold Medal for his services to African exploration.[40]

In 1902 his wife gave birth to twin boys, but neither survived more than a few hours, and they had no more children. His sister, Mabel Johnston, married Arnold Dolmetsch, an instrument maker and member of the Bloomsbury set, in 1903.

In 1903 and in 1906 he stood for parliament for the Liberal Party, but was unsuccessful on both occasions. In 1906, the Johnstons moved to the hamlet of Poling, near Arundel in West Sussex, where Harry Johnston largely concentrated on his literary endeavours. He took to writing novels, which were frequently short-lived, while his accounts of his own voyages through central Africa were rather more enduring. Some have put forward the unlikely theory that he was the principal model for 'The Man who loved Dickens' in the novel A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh.

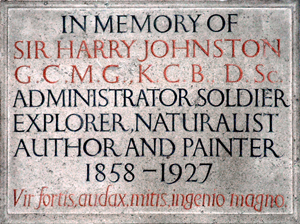

Wall plaque erected to the memory of Sir Harry Johnston in the church of St Nicholas, Poling, West Sussex. Designed and cut by Eric Gill

Harry Johnston suffered two strokes in 1925, from which he became partially paralysed and never recovered, dying two years later in 1927 at Woodsetts House near Worksop in Nottinghamshire. He was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Poling, West Sussex, where there is a commemorative wall plaque within the nave of the church designed and cut by the Arts and Crafts sculptor and typeface designer, Eric Gill who lived in nearby Ditchling. The main typeface used on the plaque appears to be Gill's Perpetua – designed in 1925, but not released until 1929 – while the lower-case typeface used for the Latin quotation below is not presently recognised.

Harry Johnston was the very model of the multi-talented African explorer; he exhibited paintings, the majority of his works, highly valued today, represent diverse aspects of wildlife, landscapes and people of Africa, collected flora and fauna (he was instrumental in bringing the okapi to the attention of science), climbed mountains, wrote books, signed treaties, and ruled colonial governments. Like his fellow imperialists he believed in British and European superiority over Africans, though he tended towards paternalistic governance rather than the use of brute force. These attitudes, which seem patronising today, were outlined in his book The Backward Peoples and Our Relations with Them (1920), but included his view that colonial rulers should try to understand the culture of the subjugated peoples. Consequently, he was considered (by white settlers) as being unusually favourable towards the native peoples (for instance his administration was one of the first in British African colonies to train and employ Africans in the colonial service as clerks and skilled staff), and he had eventually fallen out with Cecil Rhodes as a result.[citation needed]

Legacy

Harry Johnston is commemorated in the scientific names of the okapi, Okapia johnstoni and of two species of African lizards, Trioceros johnstoni and Latastia johnstoni.[41]

The falls at Mambidima on the Luapula River were named Johnston Falls by the British in his honour.

Sir Harry Johnston Primary school in Zomba, Malawi is also named after him.

Prominent Bengali author Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay mentioned the influence of Sir H. H. Johnston's works, one of many, in helping him portray scenes convincingly in his famous Bengali adventure novel Chander Pahar.

Books

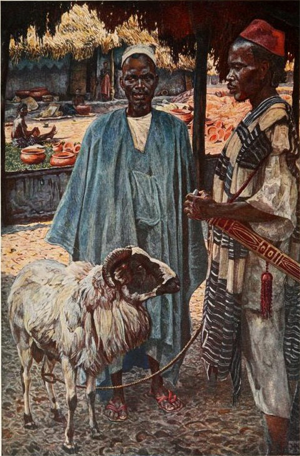

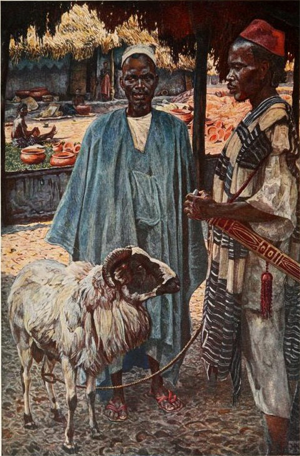

Frontispiece painting "The Negro in West Africa – Liberian Hinterland" painted by Johnston and published in his book The Negro in the New World (1910)

• The River Congo (1884)

• The Kilema-Njaro Expedition (1886)

• The History of a Slave (1889)

• British Central Africa (1897)

• The Colonization of Africa (1899)

• The Uganda Protectorate (1902)

• The Nile Quest: The Story of Exploration (1903)

• Liberia (1906)

• George Grenfell and the Congo (1908)

• The Negro in the New World (1910)

• The Opening Up of Africa (1911)

• Phonetic Spelling (1913) (online)

• A Comparative Study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu Languages (1919, 1922) (online)

• The Gay-Dombeys (1919) – a sequel to Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens

• Mrs. Warren's Daughter—a sequel to Mrs. Warren's Profession by George Bernard Shaw

• The Backward Peoples and Our Relations with Them (1920)

• The Man Who Did the Right Thing (1921) – novel

• The Story of my Life (1923) – autobiography

• The Veneerings – a sequel to Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens

The standard author abbreviation H.H.Johnst. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[42]

• Manuscripts of collected vocabularies of Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston are held by SOAS Archives

References

1. Obituary, (1927). Henry Hamilton Johnston, Ibis, Vol. XLIV, No. 1, p. 735.

2. Obituary, (1927). Henry Hamilton Johnston, Ibis, Vol. XLIV, No. 1, pp. 735–6.

3. Obituary, (1927). Henry Hamilton Johnston, Ibis, Vol. XLIV, No. 1, p. 736.

4. National Archives. "Mr Johnston's Imagination", 21 September 2017

5. K J Panton, (2015). "A Historical Dictionary of the British Empire", Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 113. ISBN 978-0-81087-801-3.

6. L Weintal, (1923). "The story of the Cape to Cairo Railway and River Route from 1887 to 1922 (Volume 4)", London, Pioneer Publishing, p. 4

7. G Harper, (2002). "Comedy, Fantasy and Colonialism", London, Bloomsbury Publications, pp. 142–3. ISBN 978-0-82644-919-1.

8. N. Ascherson, (1999). The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo p. 161, London, Granta Books

9. N. Ascherson, (1999). The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo pp. 162–3

10. F Axelson, (1967). Portugal and the Scramble for Africa, pp. 182–3, 198–200. Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press.

11. J McCracken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966", Woodbridge, James Currey, p. 51. ISBN 978-1-84701-050-6.

12. M Newitt, (1995). "A History of Mozambique", London, Hurst & Co, pp 276–7, 325–6. ISBN 1-85065-172-8

13. P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887–1895 Part II, The Nyasaland Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2, p. 39

14. Sir Harry Johnston, (1897). "British Central Africa", New York, Edward Arnold p. 81

15. O. J. M. Kalinga (1980). The Karonga War: Commercial Rivalry and Politics of Survival, Journal of African History, Vol. 21, p. 209

16. J McCraken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859-1966 pp. 57-8

17. P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887-1895 Part II, pp. 41-3

18. J McCracken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966", pp. 52–3

19. J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 53, 55

20. M Newitt, (1995). "A History of Mozambique", p 346.

21. R I Rotberg, (1965). "The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa: The Making of Malawi and Zambia", 1873–1964, Cambridge (Mass), Harvard University Press, p.15

22. Baker, C.A. (1970). Johnston's Administration: 1891–1897. Malawi Government Ministry of Local Government, Department of Antiquities, p. 21.

23. J McCraken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966" pp. 58–62

24. B Pachai, (1973). Land Policies in Malawi: An Examination of the Colonial Legacy, The Journal of African History Vol. 14 p. 685

25. Owen J. M. Kalinga, (1984). European Settlers, African Apprehensions, and Colonial Economic Policy: The North Nyasa Native Reserves Commission of 1929, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 17, No. 4, p.642

26. J McCraken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966", pp. 77–8.

27. Sir Harry Johnston, (1897). "British Central Africa", p. 85.

28. Sir Harry Johnston, (1897). "British Central Africa", pp. 112–13

29. B. Pachai, (1973). Land Policies in Malawi, pp. 682–3, 685

30. Baker, C.A. (1970). Johnston's Administration: 1891–1897. Malawi Government Ministry of Local Government, Department of Antiquities, pp. 42–4.

31. P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887–1895 Part II, pp. 43–4

32. J McCraken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966" pp. 61–3

33. A. Keppel-Jones, (1983). Rhodes and Rhodesia, 1884–1902, pp. 549–50, Kingston, McGill-Queen's University Press

34. E. A. Walker, (1963). The Cambridge History of the British Empire, Volume 1 pp. 696–7, Cambridge University Press

35. Obituary, (1927). Sir Harry H. Johnston, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 70, No. 4, pp. 415–16.

36. "No. 27377". The London Gazette. 15 November 1901. p. 7393.

37. RSGS memorial to recipients of the Livingstone Medal

38. "Zoological Society of London". The Times (36755). London. 30 April 1902. p. 6.

39. "University intelligence". The Times (36779). London. 28 May 1902. p. 12.

40. "List of Past Gold Medal Winners" (PDF). Royal Geographical Society. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

41. Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Johnston", pp. 135–136).

42. IPNI. H.H.Johnst.

Other Sources

• Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa

• Roland Oliver, "Sir Harry Johnston and the Scramble for Africa". 1958.

• James A. Casada, "Sir Harry H. Johnston: A Bio-Bibliographical Study. 1977.

External links

• Works by Harry Johnston at Project Gutenberg

• Full text of Johnston's book British Central Africa (1897). (text only)

• Full text of Johnston's book British Central Africa (1897). (facsimile)

• Works by or about Harry Johnston at Internet Archive

• Works by Harry Johnston at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• Works by Harry Johnston at Open Library

• The International Primary School which bears Sir Harry Johnston's name was founded in the early 1950s in Zomba, Malawi

• Newspaper clippings about Harry Johnston in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/3/20

Continuing their discussion of the membership of "The Society of the Elect," Stead asked permission to bring in Milner and Brett. Rhodes agreed, so they telegraphed at once to Brett, who arrived in two hours. They then drew up the following "ideal arrangement' for the society:

1. General of the Society: Rhodes

2. Junta of Three: (1) Stead, (2) Brett, (3) Milner

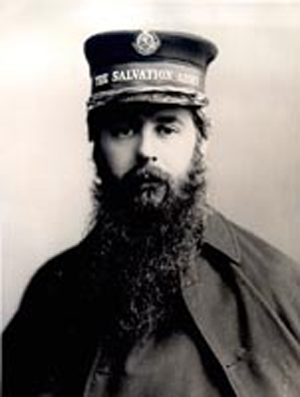

3. Circle of Initiates: (1) Cardinal Manning, (2) General Booth, (3) Bramwell Booth, (4) "Little" [Harry] Johnston, (5) Albert Grey, (6) Arthur Balfour

4. The Association of Helpers

5. A College, under Professor Seeley, to be established to train people in the English-speaking idea."

Within the next few weeks Stead had another talk with Rhodes and a talk with Milner, who was "filled with admiration" for the scheme, according to Stead's notes as published by Sir Frederick Whyte.

-- The Anglo-American Establishment: From Rhodes to Cliveden, by Carroll Quigley

Harry Johnston, by Elliott & Fry.

Sir Henry Hamilton Johnston GCMG KCB (12 June 1858 – 31 July 1927), frequently known as Harry Johnston, was a British explorer, botanist, artist, colonial administrator and linguist who traveled widely in Africa and spoke many African languages. He published 40 books on African subjects and was one of the key players in the Scramble for Africa that occurred at the end of the 19th century.

Early years

Born at Kennington Park, south London, the son of John Brookes Johnstone and Esther Laetitia Hamilton. He attended Stockwell grammar school and then King's College London, followed by four years studying painting at the Royal Academy. In connection with his study he travelled to Europe and North Africa, visiting the little-known (by Europeans) interior of Tunisia.[1]

Exploration in Africa

In 1882 he visited southern Angola with the Earl of Mayo, and in the following year met Henry Morton Stanley in the Congo, becoming one of the first Europeans after Stanley to see the river above the Stanley Pool. His developing reputation led the Royal Geographical Society and the British Association to appoint him leader of an 1884 scientific expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro. On this expedition he concluded treaties with local chiefs (which were then transferred to the British East Africa Company), in competition with German efforts to do likewise.[2]

British colonial service and the Cape to Cairo vision

In October 1886 the British government appointed him vice-consul in Cameroon and the Niger River delta area, where a protectorate had been declared in 1885, and he became acting consul in 1887,[3] deposing and banishing the local chief Jaja.

While in West Africa in 1886, Johnston sketched what has been termed a "fantasy map" of his ideas of how the African continent could be divided among the colonial powers. This envisaged two blocks of British colonies, one of continuous territory in West Africa, the Nile valley and much of East Africa as far south as Lake Tanganyika and Lake Nyasa, the other in southern Africa south of the Zambezi. This left a continuous band in Portuguese occupation from Angola to Mozambique and Germany in possession of much of the East African coast.[4]

The original proposal for a Cape to Cairo railway was made in 1874 by Edwin Arnold, the then editor of the Daily Telegraph, which was joint sponsor of the expedition by H.M. Stanley to Africa to discover the course of the Congo River.[5] The proposed route involved a mixture of railway and river transport between Elizabethville, now Lubumbashi in the Belgian Congo and Sennar in the Sudan rather than a completely rail one.[6] Johnston later acknowledged his debt to Stanley and Arnold and when on leave in England in 1888, he revived the Cape-to-Cairo concept of acquiring a continuous band of British territory down Africa in discussion with Lord Salisbury. Johnston then published an supporting the idea article in Times anonymously, as "by an African Explorer" and later in 1888 and 1889 published a number of articles in other newspapers and journals with Salisbury's tacit approval.[7]

Scramble for Katanga

The Berlin Conference had allocated Katanga to the sphere of influence of King Leopold of Belgium's Congo Free State, but under the Berlin Conference's Principle of Effectivity this was only provisional. In July 1890, Leopold protested to Lord Salisbury that Johnston, as agent for Cecil Rhodes, was circulating maps showing that the Congo Free State did not include Katanga, and in response to Salisbury's enquiries, in August 1890 Johnston presented Rhodes' claim, which included the false information that Msiri, King of Garanganze in Katanga had asked for British protection.[8]

In November 1890, to justify his claim, Johnston sent Alfred Sharpe (who would become his successor in Nyasaland) to act for Rhodes and the British South Africa Company (BSAC), to obtain a treaty with Msiri, a move which had the potential to precipitate an Anglo-Belgian crisis. Sharpe failed with Msiri, though he obtained treaties with Mwata Kazembe covering the eastern side of the Luapula River and Lake Mweru, and with other chiefs covering the southern end of Lake Tanganyika. When Leopold again protested to Salisbury in May 1891, the latter had to admit Msiri had not signed a treaty asking for British protection and left Katanga open to Belgian colonisation. In 1891 Leopold sent the Stairs Expedition to Katanga. Johnston dissuaded it from accessing Katanga through Nyasaland, but it went through German East Africa instead, and took Katanga after killing Msiri. The southern border of the Congo Free State was settled by an Anglo-Congo agreement of 1894.[9]

Nyasaland (British Central Africa Protectorate)

Portrait of Johnston by Theodore Blake Wirgman (1894)

In 1879 the Portuguese government formally claimed the area south and east of the Ruo River (currently the southeastern border of Malawi) and then, in 1882, occupied the lower Shire River valley as far north as the Ruo. It attempted to gain British acceptance of this claim without success, and also failed in a claim that the Shire Highlands was part of Portuguese East Africa, as it was not under effective occupation[10] As late as 1888, the British Foreign Office would not accept responsibility for British missionaries and settlers in the Shire Highlands after the African Lakes Corporation had tried but failed to become a Chartered company with interests there and around the western shore of Lake Malawi.[11]

However, in 1885–86 Alexandre de Serpa Pinto had undertaken an expedition which reached Shire Highlands, which had failed make any treaties of protection with the Yao chiefs west of Lake Malawi.[12] To prevent possible Portuguese occupation, in November 1888, Johnston was appointed as Commissioner and Consul-general for the Mozambique and the Nyasa districts, and arrived in Blantyre in March 1889.[13] On his way to take up his appointment, Johnston spent six weeks in Lisbon attempting to negotiate an acceptable agreement on Portuguese and British spheres of influence in southeastern Africa. However, as the draft agreement did not expressly exclude the Shire Highlands from the Portuguese sphere, it was rejected by the Foreign Office.[14]

Among several pressing problems was the Karonga War, a dispute between and Swahili traders in slaves and ivory and their Henga allies on one side and the African Lakes Trading Company and elements of the Ngonde people on the other which had broken out in 1887[15]. As Johnston had no significant forces at that time, he agreed a truce with the Swahili leaders in October 1889[16]but the Swahili traders did not adhere to its terms.[17]

In late 1888 and early 1889, the Portuguese government sent two expeditions to make treaties of protection with local chiefs, one under Antonio Cardoso set off toward Lake Malawi, the other under Alexandre de Serpa Pinto moved up the Shire valley. Between them, they made over twenty treaties with chiefs in what is now Malawi[18] Johnston met Serpa Pinto in August 1889 east of the Ruo and advised him not to cross the river, but Serpa Pinto disregarded this and crossed the river to Chiromo, now in Malawi.[19] In September, following minor clashes between Serpa Pinto's force and local Africans, Johnston's deputy declared a Shire Highlands Protectorate, despite the contrary instructions.[20] Johnston's proclamation of a further protectorate, the Nyasaland Districts Protectorate, west of Lake Malawi was endorsed by the Foreign Office in May 1891.[21]

Johnston arrived in Chiromo, in the south of Nyasaland, on 16 July 1891.[22] By that time he had already selected a team of men who were to assist in forming the administration of the new protectorate. They included Alfred Sharpe (Johnston's Deputy Commissioner), Bertram L. Sclater (Surveyor, Roadmaker, and Commandant of the Constabulary), Alexander Whyte (a zoologist who was to discover several new species in Nyasaland), Cecil Montgomery Maguire (Military Commandant), Hugh Charlie Marshall (Customs Officer, Collector of Revenues and Postmaster for the Chiromo district), John Buchanan (an agriculturalist who had been in Nyasaland since 1876, and was appointed Vice Consul by Johnston), and others.

In 1891, Johnston only controlled a fraction of the Shire Highlands, itself a small part of the whole protectorate. He was provided with a small force of Indian troops in 1891, and began to train African soldiers and police. At first, Johnston used his small force in the south of the protectorate to suppress slave trading by Yao chiefs, who had established links with Swahili traders in ivory and slaves from the early 19th century. As the Yao people had no central authority, Johnston was able to defeat one group at a time, although this took until 1894, as he left the most powerful chief, Makanjira, until almost last, starting an amphibious operation against him in late 1893.[23]

Before the British Central Africa Protectorate was proclaimed in May 1891, a number of European companies and settlers had made, or claimed to have made, treaties with local chiefs under which the land owned by the African communities that occupied it was transferred to the Europeans in exchange for protection and some trade goods.[24] The African Lakes Company claimed over 2.75 million acres in the north of the protectorate, some under treaties that claimed to transfer sovereignty to the company[25], and three others individuals claimed to have purchased large areas of land in the south. Eugene Sharrer claimed 363,034 acres, Alexander Low Bruce claimed 176,000 acres, and John Buchanan and his brothers claimed a further 167,823 acres. These lands were purchased for trivial quantities of goods under agreements signed by chiefs with no understanding of English concepts of land tenure.[26][27]

Johnston had the task of reviewing these land claims, and began to do so in late 1892, as the proclamation of the protectorate had been followed by a wholesale land grab, with huge areas of land bought for trivial sums and some claims overlapping. He rejected any suggestion that treaties made before the protectorate was established could transfer sovereignty to individuals or companies, but accept that they could be evidence of land sales. Although Johnston accepted that the land belonged to its African communities, so their chiefs had no right to alienate it, he suggested that each community had given their chief this right. Despite having no legal training, he claimed that, as Commissioner, he was entitled to investigate these land sales and to issue Certificates of Claim registering freehold title to the European claimants. He rejected very few claims, despite the questionable evidence for several major ones. The existing African villages and farms were exempted from these sales, and the villagers were told that their homes and fields were not being alienated. Despite this, the concentration of much of the most fertile land in the Shire Highlands in the hands of European owners had profound economic consequences that lasted throughout the colonial period.[28][29]

In April 1894 Johnston returned to England and was away for a year. He had quarrelled with Cecil Rhodes who had so far provided most of his funds, and during the first three years the administration had run up a deficit of £20,000. During his leave he managed to persuade the British Government to agree to take over the financing of the country. On his way back he visited Egypt and India with a view to recruiting soldiers, and eventually arrived back in Nyasaland with a flotilla of boats, 202 Sikh soldiers, and over 400 other men. 4000 porters were recruited in the Shire Highlands to carry stores and equipment. Johnston reached Zomba on 3 May 1895.[30]

Johnston visited Karonga in June 1895 to try to make a settlement but the Swahili leaders refused either to meet him curtail their raiding activities, so Johnston decided on military action.[31] In November 1895, Johnston he embarked a force of over 400 Sikh and African riflemen, with artillery and machine guns on steamers to Karonga and surrounded the traders' main stockaded town, bombarding it for two days and finally assaulting it on 4 December. The Swahili leader, Mlozi was captured, given a cursory trial and hanged on 5 December and between 200 and 300 of fighters and several hundred non-combatants were killed, many while attempting to surrender. Other Swahili stockades did not resist and were destroyed.[32]

North-Eastern Rhodesia and Nyasaland

Johnston realised the strategic importance of Lake Tanganyika to the British, especially since the territory between the lake and the coast had become German East Africa forming a break of nearly 900 km in the chain of British colonies in the Cape to Cairo dream. However the north end of Lake Tanganyika was only 230 km from British-controlled Uganda, and so a British presence at the south end of the lake was a priority. Although the northern boundaries of North-Eastern Rhodesia and Nyasaland were eventually settled by negotiations between Britain, Germany. Portugal and the Congo Free State, Johnston ensured that British bomas were established (in addition to those in Nyasaland) east of Luapula-Mweru at Chiengi and the Kalungwishi River, at the south end of Lake Tanganyika at Abercorn, and at Fort Jameson between Mozambique and the Luangwa valley to demonstrate effective occupation.[33]

Until 1899, Johnson had administrative control the territory which became North-Eastern Rhodesia (the north-eastern half of today's Zambia), and he helped to set up and oversee the British South Africa Company's administration in that area. North-Eastern Rhodesia was little developed in this period, being regarded principally as a labour reserve, with only a handful of company administrators.[34]

Although he missed out in Katanga, altogether he helped to consolidate an area of nearly half a million square kilometres into the British Empire – nearly 200,000 square miles (520,000 km2), or twice the area of the United Kingdom in 2009 – lying between the lower Luangwa River valley and lakes Nyasa, Tanganyika, and Mweru.

Later years

Okapi, from an original painting by Johnston, based on preserved skins (1901)

In 1896 in recognition of this achievement he was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB), but afflicted by tropical fevers, transferred to Tunis as consul-general. In the same year, he had married the Hon. Winifred Mary Irby, daughter of Florance George Henry Irby, fifth Baron Boston.[35]

In 1899 Sir Harry was sent to Uganda as special commissioner to end an ongoing war. He improved the colonial administration, and concluded the Buganda Agreement of 1900, dividing the land between the UK and the chiefs. For his services in Uganda, he received the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (GCMG) in the King's Birthday Honours list in November 1901.[36] Also in 1901, Johnston was the first recipient of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society's Livingstone Medal,[37] and in the following year he was appointed a member of the council of the Zoological Society of London.[38] He received the honorary degree Doctor of Science (D.Sc.) from the University of Cambridge in May 1902.[39] The Royal Geographical Society awarded him their 1904 Founder's Gold Medal for his services to African exploration.[40]

In 1902 his wife gave birth to twin boys, but neither survived more than a few hours, and they had no more children. His sister, Mabel Johnston, married Arnold Dolmetsch, an instrument maker and member of the Bloomsbury set, in 1903.

In 1903 and in 1906 he stood for parliament for the Liberal Party, but was unsuccessful on both occasions. In 1906, the Johnstons moved to the hamlet of Poling, near Arundel in West Sussex, where Harry Johnston largely concentrated on his literary endeavours. He took to writing novels, which were frequently short-lived, while his accounts of his own voyages through central Africa were rather more enduring. Some have put forward the unlikely theory that he was the principal model for 'The Man who loved Dickens' in the novel A Handful of Dust by Evelyn Waugh.

Wall plaque erected to the memory of Sir Harry Johnston in the church of St Nicholas, Poling, West Sussex. Designed and cut by Eric Gill

Harry Johnston suffered two strokes in 1925, from which he became partially paralysed and never recovered, dying two years later in 1927 at Woodsetts House near Worksop in Nottinghamshire. He was buried in the churchyard of St Nicholas, Poling, West Sussex, where there is a commemorative wall plaque within the nave of the church designed and cut by the Arts and Crafts sculptor and typeface designer, Eric Gill who lived in nearby Ditchling. The main typeface used on the plaque appears to be Gill's Perpetua – designed in 1925, but not released until 1929 – while the lower-case typeface used for the Latin quotation below is not presently recognised.

Harry Johnston was the very model of the multi-talented African explorer; he exhibited paintings, the majority of his works, highly valued today, represent diverse aspects of wildlife, landscapes and people of Africa, collected flora and fauna (he was instrumental in bringing the okapi to the attention of science), climbed mountains, wrote books, signed treaties, and ruled colonial governments. Like his fellow imperialists he believed in British and European superiority over Africans, though he tended towards paternalistic governance rather than the use of brute force. These attitudes, which seem patronising today, were outlined in his book The Backward Peoples and Our Relations with Them (1920), but included his view that colonial rulers should try to understand the culture of the subjugated peoples. Consequently, he was considered (by white settlers) as being unusually favourable towards the native peoples (for instance his administration was one of the first in British African colonies to train and employ Africans in the colonial service as clerks and skilled staff), and he had eventually fallen out with Cecil Rhodes as a result.[citation needed]

Legacy

Harry Johnston is commemorated in the scientific names of the okapi, Okapia johnstoni and of two species of African lizards, Trioceros johnstoni and Latastia johnstoni.[41]

The falls at Mambidima on the Luapula River were named Johnston Falls by the British in his honour.

Sir Harry Johnston Primary school in Zomba, Malawi is also named after him.

Prominent Bengali author Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay mentioned the influence of Sir H. H. Johnston's works, one of many, in helping him portray scenes convincingly in his famous Bengali adventure novel Chander Pahar.

Books

Frontispiece painting "The Negro in West Africa – Liberian Hinterland" painted by Johnston and published in his book The Negro in the New World (1910)

• The River Congo (1884)

• The Kilema-Njaro Expedition (1886)

• The History of a Slave (1889)

• British Central Africa (1897)

• The Colonization of Africa (1899)

• The Uganda Protectorate (1902)

• The Nile Quest: The Story of Exploration (1903)

• Liberia (1906)

• George Grenfell and the Congo (1908)

• The Negro in the New World (1910)

• The Opening Up of Africa (1911)

• Phonetic Spelling (1913) (online)

• A Comparative Study of the Bantu and Semi-Bantu Languages (1919, 1922) (online)

• The Gay-Dombeys (1919) – a sequel to Dombey and Son by Charles Dickens

• Mrs. Warren's Daughter—a sequel to Mrs. Warren's Profession by George Bernard Shaw

• The Backward Peoples and Our Relations with Them (1920)

• The Man Who Did the Right Thing (1921) – novel

• The Story of my Life (1923) – autobiography

• The Veneerings – a sequel to Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens

The standard author abbreviation H.H.Johnst. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[42]

• Manuscripts of collected vocabularies of Sir Harry Hamilton Johnston are held by SOAS Archives

References

1. Obituary, (1927). Henry Hamilton Johnston, Ibis, Vol. XLIV, No. 1, p. 735.

2. Obituary, (1927). Henry Hamilton Johnston, Ibis, Vol. XLIV, No. 1, pp. 735–6.

3. Obituary, (1927). Henry Hamilton Johnston, Ibis, Vol. XLIV, No. 1, p. 736.

4. National Archives. "Mr Johnston's Imagination", 21 September 2017

5. K J Panton, (2015). "A Historical Dictionary of the British Empire", Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield, p. 113. ISBN 978-0-81087-801-3.

6. L Weintal, (1923). "The story of the Cape to Cairo Railway and River Route from 1887 to 1922 (Volume 4)", London, Pioneer Publishing, p. 4

7. G Harper, (2002). "Comedy, Fantasy and Colonialism", London, Bloomsbury Publications, pp. 142–3. ISBN 978-0-82644-919-1.

8. N. Ascherson, (1999). The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo p. 161, London, Granta Books

9. N. Ascherson, (1999). The King Incorporated: Leopold the Second and the Congo pp. 162–3

10. F Axelson, (1967). Portugal and the Scramble for Africa, pp. 182–3, 198–200. Johannesburg, Witwatersrand University Press.

11. J McCracken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966", Woodbridge, James Currey, p. 51. ISBN 978-1-84701-050-6.

12. M Newitt, (1995). "A History of Mozambique", London, Hurst & Co, pp 276–7, 325–6. ISBN 1-85065-172-8

13. P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887–1895 Part II, The Nyasaland Journal, Vol. 18, No. 2, p. 39

14. Sir Harry Johnston, (1897). "British Central Africa", New York, Edward Arnold p. 81

15. O. J. M. Kalinga (1980). The Karonga War: Commercial Rivalry and Politics of Survival, Journal of African History, Vol. 21, p. 209

16. J McCraken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859-1966 pp. 57-8

17. P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887-1895 Part II, pp. 41-3

18. J McCracken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966", pp. 52–3

19. J McCracken, (2012). A History of Malawi, 1859–1966, pp. 53, 55

20. M Newitt, (1995). "A History of Mozambique", p 346.

21. R I Rotberg, (1965). "The Rise of Nationalism in Central Africa: The Making of Malawi and Zambia", 1873–1964, Cambridge (Mass), Harvard University Press, p.15

22. Baker, C.A. (1970). Johnston's Administration: 1891–1897. Malawi Government Ministry of Local Government, Department of Antiquities, p. 21.

23. J McCraken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966" pp. 58–62

24. B Pachai, (1973). Land Policies in Malawi: An Examination of the Colonial Legacy, The Journal of African History Vol. 14 p. 685

25. Owen J. M. Kalinga, (1984). European Settlers, African Apprehensions, and Colonial Economic Policy: The North Nyasa Native Reserves Commission of 1929, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 17, No. 4, p.642

26. J McCraken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966", pp. 77–8.

27. Sir Harry Johnston, (1897). "British Central Africa", p. 85.

28. Sir Harry Johnston, (1897). "British Central Africa", pp. 112–13

29. B. Pachai, (1973). Land Policies in Malawi, pp. 682–3, 685

30. Baker, C.A. (1970). Johnston's Administration: 1891–1897. Malawi Government Ministry of Local Government, Department of Antiquities, pp. 42–4.

31. P. T. Terry, (1965). The Arab War on Lake Nyasa 1887–1895 Part II, pp. 43–4

32. J McCraken, (2012). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966" pp. 61–3

33. A. Keppel-Jones, (1983). Rhodes and Rhodesia, 1884–1902, pp. 549–50, Kingston, McGill-Queen's University Press

34. E. A. Walker, (1963). The Cambridge History of the British Empire, Volume 1 pp. 696–7, Cambridge University Press

35. Obituary, (1927). Sir Harry H. Johnston, The Geographical Journal, Vol. 70, No. 4, pp. 415–16.

36. "No. 27377". The London Gazette. 15 November 1901. p. 7393.

37. RSGS memorial to recipients of the Livingstone Medal

38. "Zoological Society of London". The Times (36755). London. 30 April 1902. p. 6.

39. "University intelligence". The Times (36779). London. 28 May 1902. p. 12.

40. "List of Past Gold Medal Winners" (PDF). Royal Geographical Society. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

41. Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. ("Johnston", pp. 135–136).

42. IPNI. H.H.Johnst.

Other Sources

• Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa

• Roland Oliver, "Sir Harry Johnston and the Scramble for Africa". 1958.

• James A. Casada, "Sir Harry H. Johnston: A Bio-Bibliographical Study. 1977.

External links

• Works by Harry Johnston at Project Gutenberg

• Full text of Johnston's book British Central Africa (1897). (text only)

• Full text of Johnston's book British Central Africa (1897). (facsimile)

• Works by or about Harry Johnston at Internet Archive

• Works by Harry Johnston at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• Works by Harry Johnston at Open Library

• The International Primary School which bears Sir Harry Johnston's name was founded in the early 1950s in Zomba, Malawi

• Newspaper clippings about Harry Johnston in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW