The Communist Pure Land: The Legacy of Buddhist Reforms in the Early Chinese Revolutionary Periodby Kenneth J. Tymick

Illinois Wesleyan University,

ktymick@iwu.edu2014

© by Kenneth J. Tymick

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Abstract:

Prominent Buddhist Ju Zan, disciple of the venerable Taixu, saw an opportunity for Buddhism to thrive under the auspices of the Communist's period of New Democracy. However, as is usual in the retelling of history, many sides of a story are told.

In the eyes of many modern historians, the treatment of Buddhism during the 1950s seemed to be an antagonistic crackdown to subject and politicize religion. Historian Ernst Benz has compared Chinese Buddhism to that of a "religious museum under state supervision," but that was hardly the case in the immediate post-war period. In the very least, New Democracy supported religious freedom -- an aspect that Ju Zan and others hoped would legitimize their genuine efforts to reform. This paper will seek to understand how New Democracy affected Buddhism, or in reverse, how Buddhism responded to the New Democratic period in China. By examining Taixu's teachings and establishing the background for Buddhist reforms in pre-Communist China, one can perceive the myriad journal editions of Modern Buddhism (1950-1966) as a continuation of Taixu's vision to create a humanistic Buddhism. With this knowledge, it will be possible to understand that a congenial relationship existed between Buddhism and the Communist Party leading up to the late 1950s, which was due largely in part to the compatibility and joint ambition of a pure land on Earth.Keywords: China, communism, chan, buddhism, Ju Zan, Taixu, Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong, Modern Buddhism, Pure Land

Acknowledgements: Thank you to Professor Lutze, Professor Tao Jin, Siming Peng

Buddhism’s survival in the wake of the Communist Revolution in China is a peculiar instance, considering that most religion was seen then as symbolic of feudalism and imperialism—the two targets of the Communist Revolution in 1949. Even more striking was the shared view among Chinese Communists that religion was a “great hoax,” that its genesis was manufactured in a time of humanity’s immaturity, and that it was eventually “seized by the exploiting classes as an instrument of oppression.”1 Buddhism had been no stranger to oppressing the masses during its thousands of years of existence under old Confucian culture. Buddhism promoted subservience to social hierarchies through superstitions and ancient Buddhist scripture, and its monks lived like parasites, taxing the poor for religious services. But these issues were the targets that some Buddhists wished to reform. From the era surrounding the May Fourth Movement of 1919 to the start of Cultural Revolution in 1966, radical reformists sought to restore integrity to Buddhism. One such reformist was the venerable master Taixu, considered a “misguided and dangerous” influence by more conservative Dharma masters.2 Instead of encouraging Buddhism to continue its parasitic tendencies, Taixu was hopeful of a practical Buddhism that aimed at creating a heaven on earth, or, using numinous terminology, a pure land. These ideals became a dominant force throughout Communist China, and were picked up after Taixu’s death in 1947 by his converts and disciples.Ju Zan, one of Taixu’s most prominent students, saw an opportunity for Buddhism to thrive under the auspices of the Communist’s period of New Democracy. However, as is common in the retelling of history, many versions of the story have been told. In the eyes of many modern historians, the treatment of Buddhism during the 1950s seemed to be an antagonistic crackdown to subject and politicize religion. Historian Ernst Benz has compared Chinese Buddhism to that of a “religious museum under state supervision,”3 but that was hardly the case in the immediate post-war period. At the very least, New Democracy supported religious freedom—a platform that Ju Zan and others hoped would legitimize their genuine efforts to reform. This paper will seek to understand how New Democracy affected Buddhism and how Buddhism simultaneously responded to the New Democratic period in China. By examining Taixu’s teachings and establishing the background for Buddhist reforms in pre-Communist China, one can perceive the myriad journal editions of Modern Buddhism (1950-1966) as a continuation of Taixu’s vision to create a humanistic Buddhism. With this knowledge, it will be possible to understand that

a congenial relationship existed between Buddhism and the Communist Party leading up to the late 1950s, which was due largely to their ideological compatibility and the joint ambition of realizing a pure land on Earth.The overarching trend of historical retellings of the New Democratic period in China principally paint the Communist Party as a domineering overlord that viewed religious organizations, like the Chinese Buddhist Association, “as an instrument for remolding Buddhism to suit the needs of the government.”4 But one must refrain from blanketing this time period as simply an example of Communist suppression of religion.

While Communists did not think highly of religion, Chairman of the Communist Party Mao Zedong was certain to point out that religious freedom was necessary. It was not his intent to suppress it, but rather to have competing ideologies wage intellectual debates.5By examining the themes and methodologies of other historians, it can be understood that most of the secondary sources written about the Communist-Buddhist relationship during the New Democratic period are either lacking in detail or altogether inaccurate due either to ignorance of the Chinese political climate at the time or to prevailing anti-Communist sentiments that swept through the Western world after World War II. Drawing extensively on Holmes Welch’s works, there is a theme of the victimization of Buddhism under Maoism. Kenneth Chen’s article and Earl Benz’s book rebuke the Buddhist establishment for allowing Communism to control their faith. These similar themes can be attributed to the fact that they were written in the 1960s during the height of the Cold War rivalry between world communism and capitalist Western powers. Also occurring during the 1960s was the Cultural Revolution. Both internationally and domestically, this movement was deeply criticized, for it actually did suppress many facets of self-governing bodies in China, including Buddhism. But these authors mistakenly apply this time period of religious suppression to the whole existence of the People’s Government of China since its establishment in 1949, and fail to realize the freedoms that allowed and advanced many liberal reforms during the first decade of Communist power. Thus,

this paper aims to show that the Buddhist response to the New Democratic period in China featured optimism and independence, and surprisingly owed much of its preliminary success to the early guidance of the Communist Party.To prove this thesis, one must look at the primary sources of Buddhist reformers before and around this time to understand how they matched with the reforms that actually did occur under Communist authority, and also utilize more recent works by historians detached from that era of extreme bias toward China. The more objective accounts of Buddhism in Communist China, such as Pittman’s account of Taixu, and MacInnis’s impartial presentation of political documents relating to religion, give insight into what the relationship between the two parties was.

The primary sources coming from the written word of Buddhist scripture and the ideas of reform espoused by Taixu, Ju Zan, and from articles in Modern Buddhism (early 1950s), all support the changes that occurred in Buddhism during the New Democratic era. In 1955, Modern Buddhism declared, “In the not too distant future, we will completely wipe out exploitation and poverty and set up a happy, prosperous socialist society. This is the great enterprise of establishing ‘the Western Paradise on earth’ in order that all men may be released from suffering and win happiness.”6 This statement is one of many that tied together Taixu’s pre-war vision for reform with the real movements of reform in the early post-war period. Buddhists worked alongside the Communists congenially to create a new, pure China. It was their goal before the Communist Party even formed, and a look at these specific sources discredit the more biased works written by the historians in the 1960s.

To begin this study, a historical context must first be set that explains in detail the reasons why many Buddhists felt the need for reform. For generations, Chinese folklore had justified religious oppression. Typically Chinese children would learn the myths of the three most prominent religions—Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism—and thus sought during the after-life to get the benefit of all of them.7 From childhood on, the masses were instilled with notions of the importance of the after-life, indirectly implying the helplessness of their position in their current lives. It was typical in Chinese culture to pay for funeral rites so as to provide comfort for the soul of the deceased. These rites also served as a means to enable the soul to repay heavy, spiritually-concocted birth fines to the god of the dead that had allowed a soul to leave his realm and be born in the living world.8 For Buddhism, this was justified through the karmic cycle of rebirth that weighed immensely on the average mind of the peasant, and the expenses of the funeral rites would only further their ever-increasing worldly debt owed to landlords.9 Dating as far back as 819 CE, anti-Buddhist sentiment was present, and the practice of collecting birth fines was compared to atrocities committed by a group of barbarians that had ruined the peace and prosperity of China.10Death Ceremonies.As the rites in connection with a death include a considerable amount of devil worship, they may be noticed in this place.

On the occurrence of a death the body is not disturbed in any way until the Lama has extracted the soul in the orthodox manner. For it is believed that any movement of the corpse might eject the soul, which then would wander about in an irregular manner and get seized by some demon. On death, therefore, a white cloth is thrown over the face of the corpse, and the soul-extracting Lama ('p'o-bo) is sent for. On his arrival all weeping relatives are excluded from the death-chamber, so as to secure solemn silence, and the doors and windows closed, and the Lama sits down upon a mat near the head of the corpse, and commences to chant the service which contains directions for the soul to find its way to the western paradise of the mythical Buddha — Amitabha.

After advising the spirit to quit the body and its old associations and attachment to property, the Lama seizes with the fore-finger and thumb a few hairs of the crown of the corpse, and plucking these forcibly, he is supposed to give vent to the spirit of the deceased through the roots of these hairs; and it is generally believed that an actual but invisibly minute perforation of the skull is thus made, through which the liberated spirit passes.

The spirit is then directed how to avoid the dangers which beset the road to the western paradise, and it is then bid god-speed. This ceremony lasts about an hour...

Meanwhile the astrologer-Lama has been requisitioned for a death-horoscope, in order to ascertain the requisite ages and birth-years of those persons who may approach and touch the corpse, and the necessary particulars as to the date and mode of burial, as well as the worship which is to be done for the welfare of the surviving relatives.

The nature of such a horoscope will best be understood by an actual example, which I here give. It is the death-horoscope of a little girl of two years of age, who died at Darjiling in 1890...

Her Park'a being Dva in relation to her death, it is found that her spirit on quitting her body entered her loin girdle and a sword. [In this case the affected girdle was cast away and the sword was handed over to the Lama.] Her life was taken to the east by Tsan and king demons...

Her Mewa gives the "3rd Indigo blue." Thus it was the death-demon of the deceased's paternal grandfather and grandmother who caused her death; therefore take (1) a Sats-ts'a (a miniature earthern caitya), and (2) a sheep's head, and (3) earth from a variety of sites, and place these upon the body of the deceased, and this evil will be corrected.

The Day of her Death was Friday. Take to the north-west a leather bag or earthern pot in which have been placed four or five coloured articles, and throw it away as the death-demon goes there. The death having so happened, it is very bad for old men and women. On this account take a horse's skull, or a serpent's skull and place it upon the corpse.

Her Death Star is Gre. Her brother and sister who went near to her are harmed by the death-messenger (s'in-je). Therefore an ass's skull and a goat's skull must be placed on the corpse...

On obtaining this death-horoscope the body is tied up in a sitting posture by the auspicious person indicated by the horoscope, and placed in a corner of the room which is not already occupied by the house-demon.

Notice is sent to all relatives and friends within reach, and these collect within two or three days and are entertained with food of rice, vegetables, etc., and a copious supply of murwa beer and tea. This company of visitors remain loitering in and around the house, doing great execution with hand-prayer-wheels and muttering the "Om-mani" until the expulsion of the death-demon, which follows the removal of the body, and in which ceremony they all have to join.

The expense of the entertainment of so large a company is of course considerable.During this feasting, which is suggestive of an Irish "wake," the deceased is always, at every meal, offered his share of what is going, including tobacco, etc. His own bowl is kept filled with beer and tea and set down beside the corpse, and a portion of all the other eatables is always offered to him at meal times; and after the meal is over his portion is thrown away, as his spirit is supposed to have extracted all the essence of the food, which then no longer contains nutriment, and is fit only to be thrown away. And long after the corpse has been removed, his cup is regularly filled with tea or beer even up till the forty-ninth day from death, as his spirit is free to roam about for a maximum period of forty- nine days subsequent to death...

At this stage it often happens, though it is scarcely considered orthodox, that some Lamas find, as did Maudgalayana by his second-sight, consulting their lottery-books, that the spirit has been sent to hell, and the exact compartment in hell is specified. Then must be done a most costly service by a very large number of Lamas. First of all is done "virtue" on behalf of the deceased; this consists in making offerings to the Three Collections, namely: To the Gods (sacred food, lamps, etc.); to the Lamas (food and presents); to the Poor (food, clothes, beer, etc.).

The virtue resulting from these charitable acts is supposed to tell in favour of the spirit in hell. Then many more expensive services must be performed, and especially the propitiation of "The Great Pitying One," for his intercession with the king of hell (a form of himself) for the release of this particular spirit. Avalokita is behind to terminate occasionally the torment of tortured souls by casting a lotus-flower at them. Even the most learned and orthodox Lamas believe that by celebrating these services the release of a few of the spirits actually in hell may be secured. But in practice every spirit in hell for whom its relatives pay sufficiently may be released by the aid of the Lamas. Sometimes a full course of the necessary service is declared insufficient, as the spirit has only got a short way out of hell, — very suggestive of the story of the priest and his client in Lever's story, — and then additional expense must be incurred to secure its complete extraction...The ceremony of guiding the deceased's spirit is only done for the laity — the spirits of deceased Lamas are credited with a knowledge of the proper path, and need no such instruction...

But the cremation or interment of the corpse does not terminate the death-rites. There needs still to be made a masked lay figure of the deceased, and the formal burning of the mask and the expulsion from the house of the death-demon and other rites...The Lay Figure of Deceased, and its Rites.

Next day the Lamas depart, to return once a week for the repetition of this service until the forty-nine days of the ghostly limbo have expired; but it is usual to intermit one day of the first week, and the same with the succeeding periods, so as to get the worship over within a shorter time. Thus the Lamas return after six, five, four, three, two, and one days respectively, and thus conclude this service in about three weeks instead of the full term of forty-nine days...

On the conclusion of the full series of services, the paper-mask is ceremoniously burned in the flame of a butter-lamp, and the spirit is thus given its final conge. And according to the colour and quality of the flame and mode of burning is determined the fate of the spirit of deceased, and this process usually discovers the necessity for further courses of worship...

To Exorcise Ghosts.

The manes of the departed often trouble the Tibetans as well as other peoples, and special rites are necessary to "lay" them and bar their return. A ghost is always malicious, and it returns and gives trouble either on account of its malevolence, or its desire to see how its former property is being disposed of. In either case its presence is noxious. It makes its presence felt in dreams or by making some individual delirious or temporarily insane. Such a ghost is disposed of by being burned...

For this purpose a very large gathering of Lamas is necessary, not less than eight, and a "burnt offering" (sbyin-sregs) is made. On a platform of mud and stone outside the house is made, with the usual rites, a magic-circle or "kyil-'khor," and inside this is drawn a triangle named "hun-hun." Small sticks are then laid along the outline of the triangle, one piled above the other, so as to make a hollow three-sided pyramid, and around this are piled up fragments of every available kind of food, stone, tree-twigs, leaves, poison, bits of dress, money, etc., to the number of over 100 sorts. Then oil is poured over the mass, and the pile set on fire. During the combustion additional fragments of the miscellaneous ingredients reserved for the purpose are thrown in, from time to time, by the Lamas, accompanied by a muttering of spells. And ultimately is thrown into the flames a piece of paper on which is written the name of the deceased person -- always a relative -- whose ghost is to be suppressed. When this paper is consumed the particular ghost has received its quietus, and never can give trouble again...

Expelling The Death-Demon...

After a long incantation the Lama concludes: "O death-demon do thou now leave this house and go and oppress our enemies. We have given you food, fine clothes and money. Now be off far from here! Begone to the country of our enemies!! Begone!!!"...

"Dispel from this family all the sorceric injury of Pandits and Bons!! etc. Turn all these to our enemy! Begone!"...

-- The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in its Relation to Indian Buddhism, by Laurence Austine Waddell, M.B., F.L.S., F.R.G.S., Member of the Royal Asiatic Society, Anthropological Institute, etc., Surgeon-Major H.M. Bengal Army

The verses of one poem, “Idle Droning,” displayed another complaint against Buddhism’s vices.

Since earnestly studying the Buddhist doctrine of emptiness,

I’ve learned to still all the common states of mind.

Only the devil of poetry I have yet to conquer—

let me come on a bit of scenery and I start my idle droning.11

Another Chinese intellectual succinctly listed the offenses of the Buddhist religion in T’ang Era China:

First, innumerable monasteries and temples were established with a view to propagating superstition. . . . Second, many sects were founded to spread poison . . . [all in favor of the ruling class]. Third, peasants were benumbed and uprisings obstructed. . . . Buddhism was preached precisely for the purpose of preventing the peasants from rising to oppose oppression.12

It is clear from poems and complaints like these that the Buddhist sangha, or community, was a corrupt, oppressive, and parasitic establishment. Yet its power remained indisputable in Chinese culture for centuries. It was only at the turn of the twentieth century that reform could be seriously implemented. The May Fourth Movement in 1919 made real the cries for change in all facets of Chinese society, and intellectuals led the charge for the realization of a new culture.

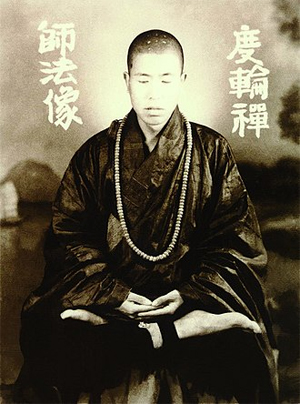

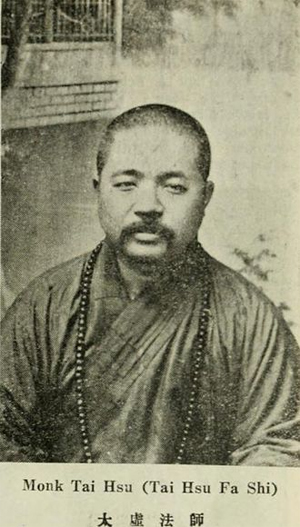

The New Culture Movement of the mid-1910s and 1920s was characterized by a sweeping call to arms to break the bonds of feudalism and imperialism oppressing the people. Under the guidance of literary elites such as Lu Xun and Chen Duxiu13 and the proliferation of Western liberal values that were expounded by such magazines as New Youth, the cultural climate became compliant to the will of the people. This genuine effort to restore the societal integrity of China was accompanied by a serious concern for the state of the Buddhist sangha. A scholar in the early Chinese Republic period, Liang Qichao, acknowledged that “the Chinese had been quite badly tainted with the poison of superstition,” and this superstition was a contributing factor to that same backwardness the New Culture Movement sought to combat.14 He continued by affirming that Buddhism “will always be an important factor in our social thinking; whether this is beneficial or baneful to our society depends solely on whether the new Buddhists appear.”15 A new Buddhism was necessary, or else it would conflict with the ideas present in a rapidly liberalizing society. Liang’s comment on social thinking sparked a new direction for Buddhism to develop toward a new moral culture.Born Lǚ Pèilín and ordained with the Dharma name, Taixu composed vast numbers of tracts and speeches detailing his desire for Buddhism to work toward a new moral culture. At the age of eighteen, four years after being ordained in a local sangha, Taixu had the opportunity to meet with a progressive Buddhist monk. Impressed by this monk,

Taixu began to broaden his learning, researching and traveling to other monasteries to develop his thoughts on modernizing the sangha. In the summer of 1910, he had the chance to begin publishing his ideas. It was at this time that he wrote, “The good student of Buddhism relies on his heart and mind, not on ancient tradition, relies on the essential meaning of words, not on the words themselves. The good student is constantly adapting to circumstances and cleverly provoking people to think.”16 Through his description of a good student, Taixu justified his developing progressive viewpoints. Taixu had realized the defects that were plaguing Buddhism and averred that

“Buddhism’s failure to remain a vital force in modern China was due to the otherworldliness of the sangha and the tendency of Buddhists to hold onto the externals of their religion without understanding its essence.”17 Buddhists strive to transcend from the samsāra, a term roughly translating to our world, or the realm in which most souls are reborn into; however, in Taixu’s opinion, that does not permit Buddhists to detach themselves from it. In fact, Taixu believed that the worldly, mundane samsāra could be transformed through a conscious moral reformation, led by Buddhism, into an idealized perfection of the western paradise on Earth. This would do away with the “Idle Droning” and parasitic funeral rites, for which Buddhism had so long been scorned.

Taixu’s ideas fully materialized during New Culture period of China, and his radical interpretation of scripture paved the way for a new Buddhism to continue to live alongside the people, rather than living off the people. His most fundamental view asserted that “[t]o achieve a lasting peace, what the world needed most fundamentally was a sweeping spiritual transformation, a universal change within the human heart that would alter the very fabric of social interaction and political engagement.”18 Once Taixu became well known in China, he traveled abroad to solicit support for a worldwide Buddhist movement toward moral transformation. The “sweeping spiritual transformation” would abide by two very simple provisions: “First, if a person harms another, both persons are harmed. Second, if a person benefits from another, both persons benefit.”19 For Taixu, these two principles were of supreme importance. Only by following this definition of morality could the world become a pure land.However, there were additional elements necessary for the sincerity of religious reform to become a reality.

Taixu believed that for reform to be successful and lasting, Buddhism needed to exhibit “genuine religious conversion...great vows to engage in compassionate service within the world...practical knowledge of how to accomplish things in the everyday world... [and] courageous moral actions that were appropriate to the uniquely dangerous circumstances of the age.”20 To provide humankind with a new moral behavior, funeral rites, superstitions, and other old, repressive ways of the sangha had to be discarded for a more dialectical, scientific approach. In this respect, practical knowledge was stressed over otherworldly meditation. Without reform, Buddhism could not survive in an increasingly secular and liberal China. As Taixu preached his revolutionary thoughts, China began to ready itself for a revolution of its own. Two major parties, the Communist Party and the Nationalist Party, would join forces in a united front to attain national unification and independence for all of China.

To prove that Buddhists could no longer divorce themselves from the physical world,

Taixu spoke extensively about revolution and was actually something of a political activist himself. As a result of being exposed to the political writings of Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao, Tan Sitong and Zhang Taiyan, Taixu turned his mind to the reformation of Buddhism. In 1911 while in Guangzhou, he made contact with the revolutionaries plotting to overthrow the Qing dynasty and participated in some secret revolutionary activities. Taixu would later describe the formation of his political thinking during this time in his Autobiography (自傳 zìzhuàn):

My social and political thought was based upon 'Mr. Constitution', the Republican Revolution, Socialism, and Anarchism. As I read works such as Zhang Taiyan's "On Establishing Religion", "On the Five Negatives", and "On Evolution", I came to see Anarchism and Buddhism as close companions, and as a possible advancement from Democratic Socialism.[6]

-- Taixu, by Wikipedia

For a pure land to exist, first peace must exist. Thus, he supported the idea of revolution, remarking once,

“Even the idea of revolution growing out of love for the people . . . is in harmony with Buddhism. . . . In the process of revolution there is always a phase of destruction preceding reconstruction.”21 Mao spoke this sentiment near verbatim in “On New Democracy,” where he said “There is no construction without destruction.”22 Despite the similarities his teachings shared with Communist ideals, Taixu distanced himself from the Party. His view that individual development and social progress were dialectically related was indeed more or less in line with socialist or communist ideology, but Taixu idolized a certain harmony between Buddhism and Nationalist Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People (sanmin zhuyi), [Nationalism (independence from foreign imperialist domination; Rights of the People (Democracy); and People's Livelihood (Socialism/Welfare] stating once that “Buddhism is the ultimate goal of Sanminism and Sanminism is Buddhism put into practice.”23 Sun Yat-sen’s Sanminism had the ultimate goal of creating a unified country with a democratic government and promoting a “land to the tiller” economic aspect to narrow the tremendous wealth gap between the peasants and the elite. In his work entitled, “Using Buddhist Dharma to Criticize Socialism,” Taixu expressed his belief that socialists strictly focus on property and neglect morality. He also noted that an outline for a period of political tutelage to teach the people democracy, like the one outlined in Sun’s Principles, was absent in socialist ideology.24 Yet in his “On New Democracy,” published in 1940, Mao introduced a platform for tutelage nearly identical to the one found in Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles, which had so absorbed Taixu.

After the Great Chinese Revolution of 1924-1927 ended abruptly with the brutal repression of Communists, Taixu continued to participate in politics until his death in 1947. The monk would find more faults with the Communist Party, arguing that while they were fighting for the benefit of the people, the poor peasant should not follow those revolutionaries who could not establish good after removing evil.25 His comment came in 1935, five years before Mao would write his plans in “On New Democracy.” Taixu’s aversion to the Communists would later be rejected by the majority of China, including his own disciples, who viewed the program of New Democracy as a resolution to the civil war that had began to be perceived as Nationalist-provoked.26 It is important to note that toward the end of his life, Taixu expressed much despair over the state of politics, suggesting his disapproval of both parties in China.27

One final note to mention was Taixu’s desire for Buddhism to be seen as more of a science than a religion because it was based on reason, not faith. In Justin R. Ritzinger’s, Taixu: To Renew Buddhism and Save the Modern World, he wrote that Taixu believed Buddhism to be “completely compatible with science since it is based not upon an untenable belief in a creator god, but upon an ‘eternal, unlimited, and absolute conception of the spiritual and material phenomena of the Universe.’”28 Unlike other religions, science and Buddhism could coexist because there are no inherent contradictions between the two; that is, so long as Buddhists interpreted sutras containing superstitions and mysticism as prescriptive rather than descriptive. More striking than his attempt to distance Buddhism from its role of religion was the idea that true religion would prepare humankind for an atheistic future.29 Taixu’s reforms were characteristic of Mahāyāna Buddhism, which perceived its teachings as a “great vehicle” serving to reach the ultimate truth, the absolute, or enlightenment. For Taixu, this nirvāṇic experience was equivalent to the pure, moral culture he wished to achieve on a worldwide scale. He wrote, “After the world honors the Dharma for a long time, the truth will be spoken, the gates of all expediencies open, the true nature of reality manifest, and atheism will still be considered the final teaching.”30 Buddhism was, perhaps unbeknownst to Taixu, advancing the goal of Mao’s Communist Party. As progressive as the monk was, the final years of Taixu’s life were marked by his impression that Communists were “simply a devil mob of wild beasts and poisonous snakes,” even though much of Taixu’s plan for a new moral culture was, ironically, in harmony with Maoist vision for a future China.31 But Taixu’s death did not end Buddhism’s reform. Many disciples of Taixu began to see what he could not—an opportunity to advance progressive reforms to the sangha under joint ambitions of the Communist Party, with the ultimate goal of a worldwide pure land. The Party could serve as a similar great vehicle, helping to educate the masses on Taixu’s lifelong endeavor of creating a universal change within the human heart. Regardless of his efforts, Taixu felt he failed in his mission given the intense polarization in the political climate of China, and was disheartened by the dire circumstances of the nation as well as the dim prospects of reform in the sangha.

The reforms Taixu fought for had been largely ignored before the Communist victory in 1949, due in part to the fact that China had been in a state of chaos for twenty years. With a new beginning, Mao and the Communist Party began to develop their vision for a united, independent, and socialized China. Returning to Mao’s concept of New Democracy, the practicality and willingness to cooperate and include all non-hostile groups in China’s future government is an issue of great significance.

The idea of a coalition government was conceived and immediately enacted when the Communists took power, and certainly went a long way in garnering widespread support for their overarching acceptance from all peoples in China. Moreover, the coalition government also protected freedom of religious belief and held that “neither compulsion nor discrimination is permitted” toward religion.33 In the actual document, “On New Democracy,” Mao did not mention religion, even under his attack on the “four olds” of old habits, ideas, customs, and culture.34 His failure to acknowledge religion signified, at the very least, that it was not a primary enemy of the new government. Under these conditions it seemed that Buddhism could be given the opportunity to thrive.

The “New China” that the Communist Party strove to create was much the same as the “pure land” that reformists in the Taixu school of Buddhism desired to achieve. For example, the Chan school of Buddhism averred that the Buddhanature, the ability to become enlightened, was inherent in all of humankind. In accordance with the Communist’s emphasis on dispelling the feudal myth that those who worked with their mind should rule over those who worked with their hands, Chan Buddhism “did not insist on intellectual efforts and prolonged periods of study in scripture...It was, therefore, egalitarian and progressive.” 35 The Communist effort to equalize land distribution among the poor and create improved living conditions both in the urban and rural areas was not contradictory to the ultimate goal of Buddhism. Social reforms put in place had, for instance, replaced patriarchal marriage laws with ones based on love and equality. Under Communist supervision, China had also managed within two years to make prostitution in the most debauched of cities vanish, and within four years, drug addiction had been wiped out.36

The Chinese journal, Modern Buddhism, ran an article propounding,[U]nder the leadership of the People’s Government . . . Everyone will cherish peace and treasure freedom. From now on there will be no wars, no disasters. From now on all the sufferings of human life will be eliminated forever. Does not this mean transforming our world into a peaceful, happy, free and beautiful Pure Land? . . . The Vimalakirti-nirdesa Sutra says: ‘If you want to get the Pure Land, you must make your mind pure. Once the mind is pure, then the land becomes pure of its own accord.’ This tells us that if we want to turn our land into the Pure Land, the first step is for the masses of the people to purify their minds. . . Fellow Buddhists, rise up with your hearts set on the Western Paradise here in the world.37

Written in 1951, these words serve as a more reliable indication of Buddhist cooperation and compatibility with the Communist Party. Based on this article’s reasoning, as the condition of human life improves, China comes closer to achieving the status of a pure land. Societal China was finally shedding its feudal and oppressive layers of the Confucian past and was working toward the general welfare of the common people.

Ju Zan, former disciple of Taixu, led the charge for Buddhist cooperation with the Communist Party and helped foster a healthy relationship between the sangha and the state. Around 1950, Ju Zan organized a group of twenty-one individuals and drafted a letter to send to Mao Zedong calling for a nationwide reform of Buddhism. Its four main points were as follows: 1. Buddhists applauded the wiping out of feudalism and superstition, and anticipated Buddhism to abandon these corrosive elements in the sangha; 2. the Communist victory allowed for the ability for Buddhism to reform based on the assertion that society was now reformed; 3. Buddhism was “atheist” in nature and advocated the “realization of selflessness” that melded congenially with Communism; and 4. the “shift to production” and “shift to scholarship” would be advanced so as to do away with feudal organizations and superstitions within the sangha indefinitely.38 The leaders of the Party accepted these points, and as a result Ju Zan was appointed to the board for the Chinese Buddhist Association and placed as Editor-in-Chief of Modern Buddhism, giving him the most authority of any Buddhist monk in directing reforms.

Modern Buddhism was produced on June 18, 1950 as a way to publicize Buddhism’s new form under the authority of the Chinese Communist Party. The journal immediately began to produce articles that would promote three main reforms for Buddhists to consider. The first two dealt with aspects derived from Taixu’s ideas, that is, the switch to an emphasis on secularizing monks by involving them in practical labor and the strive towards creation of the Pure Land. The last major point had to do with scriptural justification for killing, so as to free the Communist Party from repudiation by Buddhists. The Buddhists writing for Modern Buddhism were not forced into sending out these messages; it was on their own accord that these ideas were promulgated to the public.

For Modern Buddhism, the secularization of monks promoted an active interest in the national construction of China, and peace and purity in the country was the first step towards worldwide nirvāṇa. As a means of generating an enlightened society, the Communist Party urged productive labor for all members of the country. Buddhists adopted this same belief, not because the Communist Party forced them to, but because it had been one of Taixu’s reforms back in 1927. He believed that monks should be engaged in some form of productive labor to ensure the self-sufficiency of the monasteries.39 The healthy relationship between Buddhists and Communists started off with mutually harmonious beliefs, so when Ju Zan’s 1952 article in Modern Buddhism claimed that labor should be treated as a religious practice, it should not be mistaken for political propaganda. In the same article,

Ju Zan also wrote, “To talk about religious practices isolated from the masses of living creatures is like catching the wind and grasping at shadows . . . we can know that absolutely no one becomes a buddha while enjoying leisure in an ivory tower . . . this is just another pastime and opiate of landlords, bureaucrats, and petit bourgeois . . .”40 This mentality was simply an update of Taixu’s 1927 ideology. The relationship between Ju Zan and the Communist Party was hardly discordant given the congenial spirit of their policies.Modern Buddhism also called attention to Taixu’s intended design to reeducate monks with more modern ideas.

Chinese Communist Party reforms of the feudal superstitions and traditions present in schools of Buddhist thought have been seen primarily as aggressive, suppressive Communist atheistic policy, but Buddhists had begun this campaign long before the Communist government was even fathomed. Ju Zan wrote that only after an inner-circle meeting of the most prominent Buddhist reformists on how to improve the cultural and religious education of monks, did the discussion turn to “how to help the People’s Government get rid of charlatans who practice exorcism, sorcery, and other harmful superstitions under the guise of religion.”41 The significance is two-fold. On the one hand, these Buddhists talked freely amongst themselves, separated from the pressure of Communist supervision. Their main concern was how Buddhists could reform Buddhism, not how Communists could control its reforms. Second, the fact that these monks felt comfortable enough involving the People’s Government revealed the apparent healthy relationship between the two parties. The word choice, “to help,” indicates a friendship, not antagonism.

The main moral imperative that Modern Buddhism espoused was, of course, the creation of a terrestrial Pure Land. The impetus behind the movement for a Western Paradise on Earth had to do with the fact that only by creating such a paradise in the mortal world could Buddhist hope to be reborn in one after they died. 42 Some Buddhists began to see Communist economic reforms as an indicator of pure land development. Zhao Buchu, a monk and member of the Chinese Buddhist Association, affirmed in 1953, “The first Five-Year Plan is the initial blueprint for the Western Paradise here on earth.”43 The Five-Year Plan allowed for a larger centralized industrial and agricultural sector, thus improving the living conditions of the average Chinese. Even though the Communist Party’s outward methods of reforming China contrasted with Buddhism’s focus on inner methods to provoke change, there was no reason for Buddhism not to work with the People’s Government to achieve the ambitions of reformer monks such as Taixu. Ju Zan realized that the two parties could coexist while still working towards the same goal of bettering China—and eventually the world—eventually creating a more pure, moral, egalitarian paradise.

Chinese historian Holmes Welch cited rather poignantly from the Buddhist Avatamsaka Sutra that “no bodhisattva can attain the supreme enlightenment without living creatures” and went on to draw from it the implication that enlightenment cannot be won in isolation from the toiling masses.44 To create a pure land, Buddhism could work alongside the Communist Party in aiding the people through outward means and through the inner persuasion and cleansing of the mind which Buddhist teachings try to instill.Most controversial, however, was the effort by Modern Buddhism to justify the killing, a concept that contradicts the pacifism of the Buddha in Buddhist scripture. Another member of the Chinese Buddhist Association, Shirob Jaltso, declared once that “Buddhists should seek to keep their behavior in tune with the time and place, but doctrine and religious cultivation (hsiu-yang), that is, the Buddhist religion as such, were absolutely not open to change and this point should be firmly maintained.”45 How did Buddhists reconcile this contradiction? First, it is important to note again the autonomy of this decision. Welch attests that at this time, “The reinterpretation of Buddhist doctrine, then, was largely voluntary...”46 When other Buddhists repudiated those contributors to Modern Buddhism for aligning with the Communists who had spent years fighting the Japanese and Chinese Nationalists despite the fundamental pacifism characteristic of the faith, Ju Zan and other reformers produced

scriptures that had actually condoned killing. In one example, the great Mahayana philosopher Asanga’s clause of “preventive killing” declared that to kill a sinner to prevent further sins would gain one merit.47 Another story told of a Buddhist traveling alongside a caravan when a brigand approached him. Recognizing the Buddhist as an old friend, he opted to warn the monk that the caravan was about to be attacked by five hundred other brigands. The monk’s dilemma, according to the story, was if he told his caravan what the brigand said, they would surely kill the brigand and all suffer in hell. If he did not tell the caravan, they would all die to the brigands. The monk solved his dilemma by cutting down his old friend, the brigand. Thus, not hearing back from their scout, the five hundred bandits fled, and the monk saved 999 lives from the death of one.48

By appealing to utilitarian themes, the Buddhists of the 1950s found the justification they needed to absolve themselves from working with the “killers” of the Communist Party.

Perhaps forgotten, too, is the long history of Buddhist martial arts. The Shaolin martial practice looked to a Buddhist staff-wielding deity, whose legend “could be read therefore as a Buddhist apology for the monastic exercise of violence: if an incarnated Buddhist deity could wage war in defense of a monastery, then, by implication, Buddhist monks could do so as well.”49 Pacifism may be part of Buddhist doctrines, but so is violence in defense of Buddhism. In this respect, Buddhism and the Communist Party were in one more way congenial with each other; Taixu’s pacifism should not be misinterpreted as dogmatic among his disciples.While Taixu may have been a pacifist, there should be no confusion as to the legacy of his vision amongst Buddhist reformers like Ju Zan. As briefly mentioned earlier,

many in China felt that the Communists were victims of a violent civil war that Chiang Kai-shek of the Nationalists had prompted. Ju Zan was in the majority opinion surrounding the justness of the Communist cause, but that does not make him any less a successor to Taixu’s teachings. The maturation of Ju Zan’s ideas came about during Nationalist suppression of nationalist opposition to Japanese aggression in China. Taixu’s ideology was formulated years before in the New Culture Movement, and as such, it is not surprising that such a generational gap could produce a difference of opinion toward the legitimacy of the Communist Party.Toward the end of the 1950s, the freedom of all Chinese was seriously encroached upon with the failure of the Hundred Flowers Campaign and later Anti-Rightists Movement. What started off as an effort by Mao to encourage criticism degenerated into hostile attacks and allegations that became reminiscent of a form of reverse McCarthyism. Buddhism was not exempt from prosecution, and much of Modern Buddhism and the Chinese Buddhist Association post 1958 became heavily politicized. With a forced arm, Shirob Jaltso made a speech in 1960 where he said, “In dealing with differences between political and religious matters, we should follow the Party, not the religion, in respect of those Buddhist teachings which run counter to the policies of the Party and which are not vital to Buddhism. . . “50 Already severely restricted and tamed, Buddhism began to resemble the analogy of a state-supervised religious museum, and by 1966 the transformation was complete. Buddhism was suppressed entirely under the New Culture Movement. In 1957, Mao’s intentions for religion were made clear when he wrote in his Hundred Flowers program, “We cannot abolish religion by administrative decree nor force people not to believe. . . . The only way to settle questions of an ideological nature . . . is by the democratic method, the method of discussion, criticism, persuasion, and education, and not by the method of coercion or repression.”51 The struggle between Maoist ideologues and the bureaucratic capitalists in the Communist Party affected all of China, Buddhism included. But for a few short years, Taixu’s vision had been acted upon, and if Maoists won the battle, perhaps Buddhism could have created a Communist pure land.Regardless, what can be proved is that through an examination of Taixu’s teachings and his disciples’ actions toward the realization of his vision of a pure land on Earth, one can understand that what was once previously thought of as Communist oppression of Buddhism can be interpreted instead as a continuation of Buddhist reforms that had existed during the New Culture Movement. Articles in Modern Buddhism during most of the 1950s exemplify the ideology of Taixu, and with this knowledge it will be possible to understand that a congenial relationship existed between the Communist Party and Buddhism because of the compatibility of the pure land with the creation of a socialist state.

_______________

Notes:1. Richard C. Bush, Religion in Communist China (Nashville: Abingdon, 1970), 28.

2. Don Alvin Pittman, Toward a Modern Chinese Buddhism: Taixu’s Reforms (Honolulu: University of Hawaii, 2001), 237.

3. Ernst Benz, Buddhism or Communism (London: Allen and Unwin, 1966), 183.

4. Holmes Welch, Buddhism under Mao (Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1972), 7.

5. Mao Zedong, “On the Correct Handling of Contradictions among the People,” People’s Daily, June 19, 1957.

6. Chao P’u-ch’u, “All the Country’s Buddhists Must Struggle to Fulfill the Five-Year Plan,” Modern Buddhism (July 1955): 2.

7. A. R. Wright, “Some Chinese Folklore,” Folklore Vol. 14, No. 3 (Sep. 29, 1903): 293.

8. Ibid., 297.

9. Buddhism’s “Cycle of Rebirth” is a theory that describes different levels of rebirth. The Buddha was the pinnacle, a literal transcendence out of the endlessness of the cycle. Purchasing funeral rites was a way to gain merit, or karma, to elevate one’s rebirth. With enough Karma, a poor peasant may be reborn as a rich peasant, a king, or even a form of Buddhist deity (arhats or bodhisattvas). The inability to purchase funeral rites put one’s soul in peril, as they risked being reborn as animals, inanimate objects, or, worst, a beastly or hellish ghost. Thus, peasants exhausted their finances to avoid such a fate.

10. Edwin O. Reischauer, Ennin’s Travels in T’ang China (New York: Ronald Press, 1955), 224; Ironically, the poet who made this comparison, Han Yu, was a Confucian intellectual and xenophobe. He was especially repulsed by the “barbarian origins” of the Buddha Sakyamuni.

11. Po Chü-I: Selected Poems, trans. Burton Watson (New York: Columbia University Press 2000), 88.

12. Fen Wen-lan, Hsin Chien-she (New Construction), (October, 1965): 16.

13. Lu Xun had written many short stories for Chen Duxiu’s New Youth Magazine. Specifically, Lu’s “A New Year’s Sacrifice” spoke on the topic of reforming feudal customs that had plagued China.

14. Pittman, Taixu’s Reforms, 29.

15. Ibid., 30.

16. Yinshun, Taixu dashi nianpu (Chronological Biography), 40.

17. Pittman, Taixu’s Reforms, 71.

18. Ibid., 195

19. Taixu, “The Contribution of Religion of Modern Human Beings,” in Complete Works, 280- 281.

20. Pittman, Taixu’s Reforms, 176.

21. Taixu, “The Meaning of Buddhism,” trans. Frank R. Millican, Chinese Recorder Vol. 65, No. 11 (November 1934): 690.

22. The full quote read, “Imperialist culture and semi-feudal culture are devoted brothers and have formed a reactionary cultural alliance against China’s new culture. This kind of reactionary culture serves the imperialists and the feudal class and must be swept away. Unless it is swept away, no new culture of any kind can be built up. There is no construction without destruction, no flowing without damming and no motion without rest; the two are locked in a life-and-death struggle.” Mao Zedong, “On New Democracy,” in the Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung 1945, http://

http://www.marxists.org/reference/archi ... wv3_25.htm (April 20, 2013).

23. Pittman, Taixu’s Reforms, 184-185.

24. Taixu, “Yi fofa piping shehui zhuyi” (Using the Buddhist Dharma to Criticize Socialism), in Complete Works, 1210-1211.

25. Taixu’s exact quote read, “So if they think that they can merely remove the consequences...without realizing the need to improve the root causes, then while their aim is certainly a good one, they can only get rid of evil results but they cannot sow good seeds.” Taixu, “Using Buddhist Dharma,” 1041.

26. Chiang Kai-shek launched what become known in China as the White Terror that exterminated millions of Chinese. When Japan formally declared war on China in 1937, after years of unrepressed Japanese advancements into northern China, Chiang focused on his own civil war with the Communists.

27. Pittman, Taixu’s Reforms, 138.

28. Justin R. Ritzinger, Taixu: To Renew Buddhism and Save the Modern World.

http://enlight.lib.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/ ... ledgements (April 13 2013).

29. Pittman, Taixu’s Reforms, 251; Pittman wrote that when the absolute truth of Buddhism’s Dharma was realized, Buddhism would have no need in the world. Another way to look at the idea would be to consider Buddhism as a vehicle leading toward enlightenment, and once one is enlightened, religion is unnecessary.

30. Taixu, “Wusen lun” (On Atheism), in Complete Works, 286.

31. Paul E. Callahan, T’ai-hsü and the New Buddhist Movement, Paper on China 6 (Harvard: 1952), 167.

32. Pittman, Taixu’s Reforms, 138.

33. Mao Zedong, “On Coalition Government,” in Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung

http://www.marxists.org/reference/archi ... wv3_25.htm (March 30, 2013).

34. Donald E. MacInnis, Religious Policy and Practice in Communist China: A Documentary History (New York: Macmillan, 1972), 4.

35. Kenneth Chen, “Chinese Communist Attitudes Towards Buddhism in Chinese History.” The China Quarterly 22 (April-June, 1965): 19.

36. Thomas Lutze, “The Chinese Revolution,” Lecture. Liberation: Continuing the Revolution (Illinois Wesleyan University, Bloomington, March 22, 2013). For more information on marriage laws in China, read Ono Kazuko’s “The Impact of the Marriage Law of 1950,” Chinese Women in a Century of Revolution: 1850-1950 (Stanford: Stanford UP, 1989), and for more on how drug addiction was handled, read Nancy Southwell, “Kicking the Habit: How China Cured its Drug Addicts,” in New China Vol. 1, No. 3 (Fall 1975).

37. Modern Buddhism (June 1951): 146.

38. Welch, Buddhism under Mao, 395-396.

39. Pittman, Taixu’s Reforms, 233. Taken from Taixu, “Sengzhi jinlun” (A Current Discussion of the Monastic System), in Complete Works, 195-199.

40. Modern Buddhism (April 1952): 145-146.

41. Ju Zan, “A Buddhist Monk’s Life,” China Reconstructs III (January-February, 1954), 42-44.

42. Welch, Buddhism under Mao, 596.

43. Bush, Religion in Communist China, 333.

44. Holmes Welch, “The Reinterpretation of Chinese Buddhism,” The Chinese Quarterly 22 (June, 1965): 148.

45. Modern Buddhism (Oct. 1959): 10-15

46. Welch, “Chinese Buddhism,” 152.

47. Welch, Buddhism under Mao, 282.

48. Ibid.

49. Meir Shahar, “Ming-Period Evidence of Shaolin Martial Practice,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies Vol. 61, No. 2 (Dec. 2001): 404-405.

50. Jen-min Jih-pao (People’s Daily), (April 15, 1960).

51. Mao Zedong, “Correct Handling.”