Part 2 of 2

Legacy

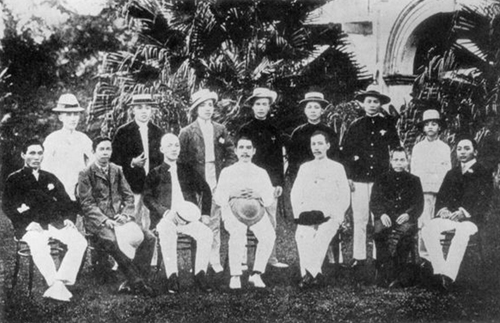

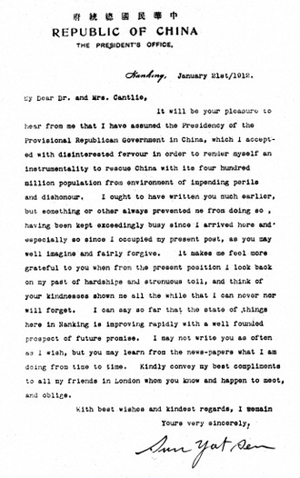

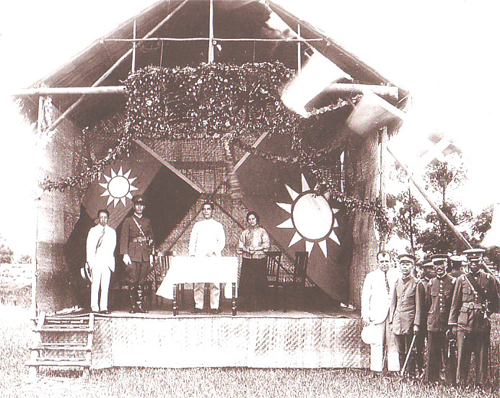

Power struggle Chinese generals at the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum in 1928 after the Northern Expedition. From right: Cheng Jin (何成浚), Zhang Zuobao (張作寶), Chen Diaoyuan (陳調元), Chiang Kai-shek, Woo Tsin-hang, Yan Xishan, Ma Fuxiang, Ma Sida (馬四達), and Bai Chongxi.

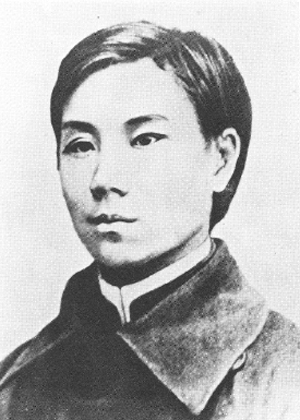

Chinese generals at the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum in 1928 after the Northern Expedition. From right: Cheng Jin (何成浚), Zhang Zuobao (張作寶), Chen Diaoyuan (陳調元), Chiang Kai-shek, Woo Tsin-hang, Yan Xishan, Ma Fuxiang, Ma Sida (馬四達), and Bai Chongxi.After Sun's death, a power struggle between his young protégé Chiang Kai-shek and his old revolutionary comrade Wang Jingwei split the KMT. At stake in this struggle was the right to lay claim to Sun's ambiguous legacy. In 1927 Chiang Kai-shek married Soong Mei-ling, a sister of Sun's widow Soong Ching-ling, and subsequently he could claim to be a brother-in-law of Sun. When the Communists and the Kuomintang split in 1927, marking the start of the Chinese Civil War, each group claimed to be his true heirs, a conflict that continued through World War II. Sun's widow, Soong Ching-ling, sided with the Communists during the Chinese Civil War and served from 1949 to 1981 as Vice-President (or Vice-Chairwoman) of the People's Republic of China and as Honorary President shortly before her death in 1981.

Cult of personalityA personality cult in the Republic of China was centered on Sun and his successor, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Chinese Muslim Generals and Imams participated in this cult of personality and one party state, with Muslim General Ma Bufang making people bow to Sun's portrait and listen to the national anthem during a Tibetan and Mongol religious ceremony for the Qinghai Lake God.[108] Quotes from the Quran and Hadith were used among Hui Muslims to justify Chiang Kai-shek's rule over China.[109]

The Kuomintang's constitution designated Sun as party president. After his death, the Kuomintang opted to keep that language in its constitution to honor his memory forever. The party has since been headed by a director-general (1927–1975) and a chairman (since 1975), which discharge the functions of the president.

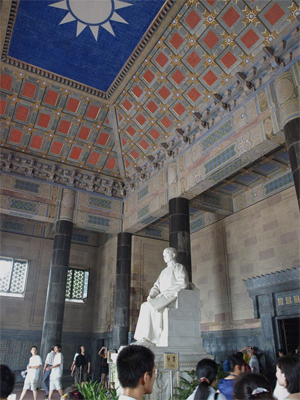

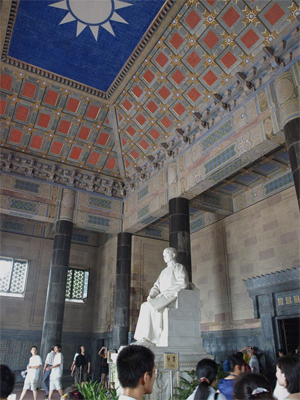

Father of the Nation Statue in the Mausoleum, Kuomintang flag on the ceiling

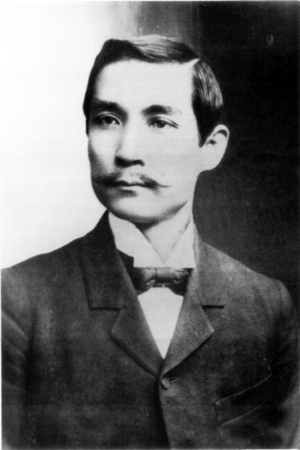

Statue in the Mausoleum, Kuomintang flag on the ceilingSun Yat-sen remains unique among 20th-century Chinese leaders for having a high reputation both in mainland China and in Taiwan. In Taiwan, he is seen as the Father of the Republic of China, and is known by the posthumous name Father of the Nation, Mr. Sun Zhongshan (Chinese: 國父 孫中山先生, where the one-character space is a traditional homage symbol).[8] His likeness is still almost always found in ceremonial locations such as in front of legislatures and classrooms of public schools, from elementary to senior high school, and he continues to appear in new coinage and currency.

"Forerunner of the revolution"On the mainland, Sun is seen as a Chinese nationalist, proto-socialist, first president of a Republican China and is highly regarded as the Forerunner of the Revolution (革命先行者).[3] He is even mentioned by name in the preamble to the Constitution of the People's Republic of China. In recent years, the leadership of the Communist Party of China has increasingly invoked Sun, partly as a way of bolstering Chinese nationalism in light of Chinese economic reform and partly to increase connections with supporters of the Kuomintang on Taiwan which the PRC sees as allies against Taiwan independence. Sun's tomb was one of the first stops made by the leaders of both the Kuomintang and the People First Party on their pan-blue visit to mainland China in 2005.[110] A massive portrait of Sun continues to appear in Tiananmen Square for May Day and National Day.

Economic developmentSun Yat-sen spent years in Hawaii as a student in the late 1870s and early 1880s, and was highly impressed with the economic development he saw there. He used the independent Kingdom of Hawaii as a model to develop his vision of a technologically modern and politically independent and actively anti-imperialist China.[111] Sun Yat-sen was an important pioneer of international development, proposing in the 1920s international institutions of the sort that appeared after World War II. He focused on China, with its vast potential and weak base of mostly local entrepreneurs.[112] His key proposal was socialism. He proposed:

The State will take over all the large enterprises; we shall encourage and protect enterprises which may reasonably be entrusted to the people; the nation will possess equality with other nations; every Chinese will be equal to every other Chinese both politically and in his opportunities of economic advancement.[113]

FamilyMain article: Family tree of Sun Yat-sen

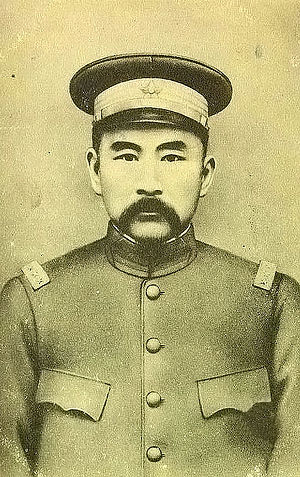

Lu Muzhen (1867–1952), Sun's first wife from 1885 to 1915

Lu Muzhen (1867–1952), Sun's first wife from 1885 to 1915Sun Yat-sen was born to Sun Dacheng (孫達成) and his wife, Lady Yang (楊氏) on 12 November 1866.[114] At the time his father was age 53, while his mother was 38 years old. He had an older brother, Sun Dezhang (孫德彰), and an older sister, Sun Jinxing (孫金星), who died at the early age of 4. Another older brother, Sun Deyou (孫德祐), died at the age of 6. He also had an older sister, Sun Miaoqian (孫妙茜), and a younger sister, Sun Qiuqi (孫秋綺).[24]

At age 20, Sun had an arranged marriage with fellow villager Lu Muzhen. She bore a son, Sun Fo, and two daughters, Sun Jinyuan (孫金媛) and Sun Jinwan (孫金婉).[24] Sun Fo was the grandfather of Leland Sun, who spent 37 years working in Hollywood as an actor and stuntman.[115] Sun Yat-sen was also the godfather of Paul Myron Anthony Linebarger, American author and poet who wrote under the name Cordwainer Smith.[116]

Sun's first concubine, the Hong Kong-born Chen Cuifen, lived in Taiping, Perak, Malaysia for 17 years. The couple adopted a local girl as their daughter. Cuifen subsequently relocated to China, where she died.[117]

On 25 October 1915 in Japan, Sun married Soong Ching-ling, one of the Soong sisters,[24][118] Soong Ching-Ling's father was the American-educated Methodist minister Charles Soong, who made a fortune in banking and in printing of Bibles. Although Charles Soong had been a personal friend of Sun's, he was enraged when Sun announced his intention to marry Ching-ling because while Sun was a Christian he kept two wives, Lu Muzhen and Kaoru Otsuki; Soong viewed Sun's actions as running directly against their shared religion.

Soong Ching-Ling's sister, Soong Mei-ling, later married Chiang Kai-shek.

Cultural references

Memorials and structures in Asia Aerial perspective of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall in central Singapore. Taken in 2016

Aerial perspective of Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall in central Singapore. Taken in 2016In most major Chinese cities one of the main streets is named Zhongshan Lu (中山路) to celebrate his memory. There are also numerous parks, schools, and geographical features named after him. Xiangshan, Sun's hometown in Guangdong, was renamed Zhongshan in his honor, and there is a hall dedicated to his memory at the Temple of Azure Clouds in Beijing. There are also a series of Sun Yat-sen stamps.

Other references to Sun include the Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou and National Sun Yat-sen University in Kaohsiung. Other structures include Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall subway station, Sun Yat-sen house in Nanjing, Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum in Hong Kong, Chung-Shan Building, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Guangzhou, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall in Taipei and Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall in Singapore. Zhongshan Memorial Middle School has also been a name used by many schools. Zhongshan Park is also a common name used for a number of places named after him. The first highway in Taiwan is called the Sun Yat-sen expressway. Two ships are also named after him, the Chinese gunboat Chung Shan and Chinese cruiser Yat Sen. The old Chinatown in Calcutta (now known as Kolkata), India has a prominent street by the name of Sun Yat-sen street. There are also two streets named after Sun Yat-sen, located in the cities of Astrakhan and Ufa, Russia.

In George Town, Penang, Malaysia, the Penang Philomatic Union had its premises at 120 Armenian Street in 1910, during the time when Sun spent more than four months in Penang, convened the historic "Penang Conference" to launch the fundraising campaign for the Huanghuagang Uprising and founded the Kwong Wah Yit Poh; this house, which has been preserved as the Sun Yat-sen Museum (formerly called the Sun Yat Sen Penang Base), was visited by President designate Hu Jintao in 2002. The Penang Philomatic Union subsequently moved to a bungalow at 65 Macalister Road which has been preserved as the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Centre Penang.

As dedication, the 1966 Chinese Cultural Renaissance was launched on Sun's birthday on 12 November.[119]

The Nanyang Wan Qing Yuan in Singapore have since been preserved and renamed as the Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall.[65] A Sun Yat-sen heritage trail was also launched on 20 November 2010 in Penang.[120]

Sun's US citizen Hawaii birth certificate that show he was not born in the ROC, but instead born in the US was on public display at the American Institute in Taiwan on US Independence day 4 July 2011.[121]

A street in Medan, Indonesia is named "Jalan Sun Yat-Sen" in honour of him.[122]

A street named "Tôn Dật Tiên" (Sino-Vietnamese name for Sun Yat-Sen) is located in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Memorials and structures outside of Asia Sun Yat-Sen monument in Chinatown area of Los Angeles, California

Sun Yat-Sen monument in Chinatown area of Los Angeles, CaliforniaSt. John's University in New York City has a facility built in 1973, the Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hall, built to resemble a traditional Chinese building in honor of Sun.[123] Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden is located in Vancouver, the largest classical Chinese gardens outside of Asia. There is the Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park in Chinatown, Honolulu.[124] On the island of Maui, there is the little Sun Yat-sen Park at Kamaole. It is located near to where his older brother had a ranch on the slopes of Haleakala in the Kula region.[15][16][17][44]

In Chinatown, Los Angeles, there is a seated statue of him in Central Plaza.[125] In Sacramento, California there is a bronze statue of Sun in front of the Chinese Benevolent Association of Sacramento. Another statue of Sun Yat-sen by Joe Rosenthal can be found at Riverdale Park in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. There is also the Moscow Sun Yat-sen University. In Chinatown, San Francisco, there is a 12-foot statue of him on Saint Mary's Square.[126]

In late 2011, the Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne, in celebration of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of China, unveiled, in a Lion Dance Blessing ceremony, a memorial statue of Sun outside the Chinese Museum in Melbourne's Chinatown, on the spot where their traditional Chinese New Year Lion Dance always ends.[127]

Sun Yat-Sen plaza in the Chinese Quarter of Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Sun Yat-Sen plaza in the Chinese Quarter of Montreal, Quebec, CanadaIn 1993 Lily Sun, one of Sun Yat-sen's granddaughters, donated books, photographs, artwork and other memorabilia to the Kapi'olani Community College library as part of the "Sun Yat-sen Asian collection".[128] During October and November every year the entire collection is shown.[128] In 1997 the "Dr Sun Yat-sen Hawaii foundation" was formed online as a virtual library.[128] In 2006 the NASA Mars Exploration Rover Spirit labeled one of the hills explored "Zhongshan".[129]

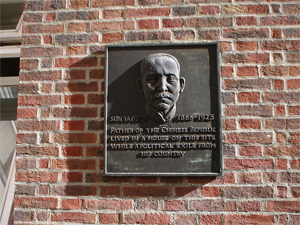

The plaque shown earlier in this article is by Dora Gordine, and is situated on the site of Sun's lodgings in London in 1896, 8 Grays Inn Place. There is also a blue plaque commemorating Sun at The Kennels, Cottered, Hertfordshire, the country home of the Cantlies where Sun came to recuperate after his rescue from the legation in 1896.[citation needed]

A street named Sun Yat-Sen Avenue is located in Markham, Ontario. This is the first such street name outside of Asia.

In popular culture

Opera Sun Yat-sen tribute in Tiananmen Square, 2010

Sun Yat-sen tribute in Tiananmen Square, 2010Dr. Sun Yat-sen[130] (中山逸仙; ZhōngShān yì xiān) is a 2011 Chinese-language western-style opera in three acts by the New York-based American composer Huang Ruo who was born in China and is a graduate of Oberlin College's Conservatory as well as the Juilliard School. The libretto was written by Candace Mui-ngam Chong, a recent collaborator with playwright David Henry Hwang.[131] It was performed in Hong Kong in October 2011 and was given its North American premiere on 26 July 2014 at The Santa Fe Opera.

TV series and filmsThe life of Sun is portrayed in various films, mainly The Soong Sisters and Road to Dawn. A fictionalized assassination attempt on his life was featured in Bodyguards and Assassins. He is also portrayed during his struggle to overthrow the Qing dynasty in Once Upon a Time in China II. The TV series Towards the Republic features Ma Shaohua as Sun Yat-sen. In the 100th anniversary tribute of the film 1911, Winston Chao played Sun.[132] In Space: Above and Beyond, one of the starships of the China Navy is named the Sun Yat-sen.[133]

PerformancesIn 2010, a theatrical play Yellow Flower on Slopes (斜路黃花) was created and performed.[134] In 2011, there is also a Mandopop group called "Zhongsan Road 100" (中山路100號) known for singing the song "Our Father of the Nation" (我們國父).[135]

Controversy

New Three Principles of the PeopleAt one time CPC general secretary and PRC president Jiang Zemin claimed that Sun Yat-sen advocated a movement known as the "New Three Principles of the People" (新三民主義) which consisted of "working with the soviets, working with the communists and helping the farmers" (聯俄, 聯共, 扶助工農).[136][137] In 2001 Lily Sun said that the CPC was distorting Sun's legacy. She then voiced her displeasure in 2002 in a private letter to Jiang about the distortion of history.[136] In 2008 Jiang Zemin was willing to offer US$10 million to sponsor a Xinhai Revolution anniversary celebration event. According to Ming Pao she could not take the money because she would no longer have the freedom to communicate about the revolution.[136] This concept is still currently available on Baike Baidu.

KMT emblem removal caseIn 1981, Lily Sun took a trip to Sun Yat-sen mausoleum in Nanjing, People's Republic of China. The emblem of the KMT had been removed from the top of his sacrificial hall at the time of her visit, but was later restored. On another visit in May 2011, she was surprised to find the four characters "General Rules of Meetings" (會議通則), a document that Sun wrote in reference to Robert's Rules of Order had been removed from a stone carving.[136]

Father of Independent Taiwan issueFurther information: North South divide in Taiwan

In November 2004, the ROC Ministry of Education proposed that Sun Yat-sen was not the father of Taiwan. Instead, Sun was a foreigner from mainland China.[138] Taiwanese Education minister Tu Cheng-sheng and Examination Yuan member Lin Yu-ti [zh], both of whom supported the proposal, had their portraits pelted with eggs in protest.[139] At a Sun Yat-sen statue in Kaohsiung, a 70-year-old ROC retired soldier committed suicide as a way to protest the ministry proposal on the anniversary of Sun's birthday 12 November.[138][139]

Works• The Outline of National Reconstruction/Chien Kuo Ta Kang (1918)

• The Fundamentals of National Reconstruction/Jianguo fanglue (1924)

• The Principle of Nationalism (1953)

See also• China portal

• Taiwan portal

• Biography portal

• Chiang Kai-shek

• Chinese Anarchism

• History of the Republic of China

• Politics of the Republic of China

• Sun Yat-sen Museum Penang

• United States Constitution and worldwide influence

• Zhongshan suit

Notes1. Contrary to popular legends, Sun entered the Legation voluntarily, but was prevented from leaving. The Legation planned to execute him, before returning his body to Beijing for ritual beheading. Cantlie, his former teacher, was refused a writ of habeas corpus because of the Legation's diplomatic immunity, but he began a campaign through The Times. The Foreign Office persuaded the Legation to release Sun through diplomatic channels.[53]

References1. Singtao daily. Saturday edition. 23 October 2010. 特別策劃 section A18. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition 民國之父.

2. "Chronology of Dr. Sun Yat-sen". National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

3. Tung, William L. [1968] (1968). The political institutions of modern China. Springer publishing. ISBN 9789024705528. p 92. P106.

4. Barth, Rolf F.; Chen, Jie (2 September 2016). "What did Sun Yat-sen really die of? A re-assessment of his illness and the cause of his death". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 35 (1): 81. doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0144-9. PMC 5009495. PMID 27586157.

5. "Three Principles of the People". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

6. Schoppa, Keith R. [2000] (2000). The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. Columbia university press. ISBN 0231500378, ISBN 9780231500371. p 73, 165, 186.

7. Sun Yat-sen (3 August 1924). "三民主義:民生主義 第一講 [Three Principles of the People : People's living]". 國父全集 [Father of the nation's scripts]. 中山學術資料庫系統 (in Chinese). pp. 0129–0145. Retrieved 30 December 2019. 我們國民黨提倡民生主義,已經有了二十多年,不講社會主義,祇講民生主義。社會主義和民生主義的範圍是甚麼關係呢?近來美國有一位馬克思的信徒威廉氏,深究馬克思的主義,見得自己同門互相紛爭,一定是馬克思學說還有不充分的地方,所以他便發表意見,說馬克思以物質為歷史的重心是不對的,社會問題才是歷史的重心;而社會問題中又以生存為重心,那才是合理。民生問題就是生存問題......

8. Wang, Ermin (王爾敏) (April 2011). 思想創造時代:孫中山與中華民國. Showwe Information Co., Ltd. p. 274. ISBN 978-986-221-707-8.

9. Wang, Shounan (王壽南) (2007). Sun Zhong-san. Commercial Press Taiwan. p. 23. ISBN 978-957-05-2156-6.

10. 游梓翔 (2006). 領袖的聲音: 兩岸領導人政治語藝批評, 1906–2006. Wu-Nan Book Inc. p. 82. ISBN 978-957-11-4268-5.

11. 门杰丹 (4 December 2003). 浓浓乡情系中原—访孙中山先生孙女孙穗芳博士 [Central Plains Nostalgia-Interview with Dr. Sun Suifang, granddaughter of Sun Yat-sen]. China News (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Translate this Chinese article to English

12. Bohr, P. Richard (2009). "Did the Hakka Save China? Ethnicity, Identity, and Minority Status in China's Modern Transformation". Headwaters. 26 (3): 16.

13. Sun Yat-sen. Stanford University Press. 1998. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8047-4011-1.

14. Kubota, Gary (20 August 2017). "Students from China study Sun Yat-sen on Maui". Star-Advertiser. Honolulu. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

15. KHON web staff (3 June 2013). "Chinese government officials attend Sun Mei statue unveiling on Maui". KHON2. Honolulu. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

16. "Sun Yat-sen Memorial Park". Hawaii Guide. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

17. "Sun Yet Sen Park". County of Maui. Retrieved 21 August 2017.[permanent dead link]

18. "Dr. Sun Yat-Sen (class of 1882)". ʻIolani School website. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

19. Brannon, John (16 August 2007). "Chinatown park, statue honor Sun Yat-sen". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. Retrieved 17 August2007. Sun graduated from Iolani School in 1882, then attended Oahu College—now known as Punahou School—for one semester.

20. 基督教與近代中國革命起源:以孫中山為例. Big5.chinanews.com:89. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

21. 歷史與空間:基督教與近代中國革命的起源──以孫中山為例 – 香港文匯報. Paper.wenweipo.com. 2 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

22. 中山史蹟徑一日遊. Lcsd.gov.hk. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

23. HK university. [2002] (2002). Growing with Hong Kong: the University and its graduates: the first 90 years. ISBN 962-209-613-1, ISBN 978-962-209-613-4.

24. Singtao daily. 28 February 2011. 特別策劃 section A10. Sun Yat-sen Xinhai revolution 100th anniversary edition.

25. South China morning post. Birth of Sun heralds dawn of revolutionary era for China. 11 November 1999.

26. [1], Sun Yat-sen and Christianity.

27. "...At present there are some seven members in the interior belonging to our mission, and two here, one I baptized last Sabbath,a young man who is attending the Government Central School. We had a very pleasant communion service yesterday..." – Hager to Clark, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.17, p.3

28. "...We had a pleasant communion yesterday and received one Chinaman into the church..." – Hager to Pond, 5 May 1884, ABC 16.3.8: South China v.4, no.18, p.3 postscript

29. Rev. C. R. Hager, 'The First Citizen of the Chinese Republic', The Medical Missionary v.22 1913, p.184

30. Bergère: 26

31. Soong, (1997) p. 151-178

32. 中西區區議會 [Central & Western District Council] (November 2006), 孫中山先生史蹟徑 [Dr Sun Yat-sen Historical Trail] (PDF), Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum (in Chinese and English), Hong Kong, China: Dr. Sun Yat-sen Museum, p. 30, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2012, retrieved 15 September 2012

33. Bard, Solomon. Voices from the past: Hong Kong, 1842–1918. [2002] (2002). HK university press. ISBN 962-209-574-7, ISBN 978-962-209-574-8. p. 183.

34. Curthoys, Ann. Lake, Marilyn. [2005] (2005). Connected worlds: history in transnational perspective. ANU publishing. ISBN 1-920942-44-0, ISBN 978-1-920942-44-1. pg 101.

35. Wei, Julie Lee. Myers Ramon Hawley. Gillin, Donald G. [1994] (1994). Prescriptions for saving China: selected writings of Sun Yat-sen. Hoover press. ISBN 0-8179-9281-2, ISBN 978-0-8179-9281-1.

36. 王恆偉 (2006). #5 清 [Chapter 5. Qing dynasty]. 中國歷史講堂. 中華書局. p. 146. ISBN 962-8885-28-6.

37. Bergère: 39–40

38. Bergère: 40–41

39. (Chinese) Yang, Bayun; Yang, Xing'an (November 2010). Yeung Ku-wan – A Biography Written by a Family Member. Bookoola. p. 17. ISBN 978-988-18-0416-7

40. Faure, David (1997). Society. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622093935., founder Tse Tsan-tai's account

41. 孫中山第一次辭讓總統並非給袁世凱 – 文匯資訊. Info.wenweipo.com. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

42. Bevir, Mark. [2010] (2010). Encyclopedia of Political Theory. Sage publishing. ISBN 1-4129-5865-2, ISBN 978-1-4129-5865-3. pg 168.

43. Lin, Xiaoqing Diana. [2006] (2006). Peking University: Chinese Scholarship And Intellectuals, 1898–1937. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-6322-2, ISBN 978-0-7914-6322-2. pg 27.

44. Paul Wood (November–December 2011). "The Other Maui Sun". Wailuku, Hawaii: Maui Nō Ka ʻOi Magazine. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

45. "JapanFocus". Old.japanfocus.org. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

46. Thornber, Karen Laura. [2009] (2009). Empire of Texts in Motion: Chinese, Korean, and Taiwanese Transculturations of Japanese Literature. Harvard university press. pg 404.

47. Ocampo, Ambeth (2010). Looking Back 2. Pasig City: Anvil Publishing. pp. 8–11.

48. Gao, James Zheng. [2009] (2009). Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949). Scarecrow press. ISBN 0-8108-4930-5, ISBN 978-0-8108-4930-3. Chronology section.

49. Bergère: 86

50. 劉崇稜 (2004). 日本近代文學精讀. p. 71. ISBN 978-957-11-3675-2.

51. Frédéric, Louis. [2005] (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Harvard university press. ISBN 0-674-01753-6, ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5. pg 651.

52. "Sun Yat-sen | Chinese leader". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

53. Wong, J.Y. (1986). The Origins of a Heroic Image: SunYat Sen in London, 1896–1987. Hong Kong: Oxford University Press.

as summarized in

Clark, David J.; Gerald McCoy (2000). The Most Fundamental Legal Right: Habeas Corpus in the Commonwealth. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 162. ISBN 9780198265849.

54. Cantlie, James (1913). Sun Yat Sen and the Awakening of China. London: Jarrold & Sons.

55. João de Pina-Cabral. [2002] (2002). Between China and Europe: person, culture and emotion in Macao. Berg publishing. ISBN 0-8264-5749-5, ISBN 978-0-8264-5749-3. pg 209.

56. England, Vaudine (17 September 2007). "Hong Kong rediscovers Sun Yat-sen". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

57. 孫中山思想 3學者演說精采. World journal. 4 March 2011. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

58. "Sun Yat-sen: Certification of Live Birth in Hawaii". San Francisco, CA, USA: Scribd. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

59. Smyser, A.A. (2000). Sun Yat-sen's strong links to Hawaii. Honolulu Star Bulletin. "Sun renounced it in due course. It did, however, help him circumvent the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which became applicable when Hawaii was annexed to the United States in 1898."

60. Department of Justice. Immigration and Naturalization Service. San Francisco District Office. "Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925" (PDF). Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787–2004 ]. Washington, DC, USA: National Archives and Records Administration. pp. 92–152. Immigration Arrival Investigation case file for SunYat Sen, 1904–1925 at the National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2012. Note that one immigration official recorded that Sun Yat-sen was born in Kula, a district of Maui, Hawaii.

61. 計秋楓, 朱慶葆. [2001] (2001). 中國近代史, Volume 1. Chinese university press. ISBN 962-201-987-0, ISBN 978-962-201-987-4. pg 468.

62. "Internal Threats – The Manchu Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) – Imperial China – History – China – Asia". Countriesquest.com. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

63. Streets of George Town, Penang. Areca Books. 2007. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-983-9886-00-9.

64. Yan, Qinghuang. [2008] (2008). The Chinese in Southeast Asia and beyond: socioeconomic and political dimensions. World Scientific publishing. ISBN 981-279-047-0, ISBN 978-981-279-047-7. pg 182–187.

65. "Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall". Wanqingyuan.org.sg. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

66. "United Chinese Library". Roots. National Heritage Board.

67. Eiji Murashima. "The Origins of Chinese Nationalism in Thailand" (PDF). Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies (Waseda University). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 March 2017. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

68. Eric Lim. "Soi Sun Yat Sen the legacy of a revolutionary". Tour Bangkok Legacies. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

69. Khoo, Salma Nasution. [2008] (2008). Sun Yat Sen in Penang. Areca publishing. ISBN 983-42834-8-2, ISBN 978-983-42834-8-3.

70. Tang Jiaxuan. [2011] (2011). Heavy Storm and Gentle Breeze: A Memoir of China's Diplomacy. HarperCollins publishing. ISBN 0-06-206725-7, ISBN 978-0-06-206725-8.

71. Nanyang Zonghui bao. The Union Times paper. 11 November 1909 p2.

72. Bergère: 188

73. 王恆偉. (2005) (2006) 中國歷史講堂 No. 5 清. 中華書局. ISBN 962-8885-28-6. p 195-198.

74. Bergère: 210

75. Carol, Steven. [2009] (2009). Encyclopedia of Days: Start the Day with History. iUniverse publishing. ISBN 0-595-48236-8, ISBN 978-0-595-48236-8.

76. Lane, Roger deWardt. [2008] (2008). Encyclopedia Small Silver Coins. ISBN 0-615-24479-3, ISBN 978-0-615-24479-2.

77. Welland, Sasah Su-ling. [2007] (2007). A Thousand miles of dreams: The journeys of two Chinese sisters. Rowman littlefield publishing. ISBN 0-7425-5314-0, ISBN 978-0-7425-5314-9. pg 87.

78. Fu, Zhengyuan. (1993). Autocratic tradition and Chinese politics(Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44228-1, ISBN 978-0-521-44228-2). pp. 153–154.

79. Bergère: 226

80. Ch'ien Tuan-sheng. The Government and Politics of China 1912–1949. Harvard University Press, 1950; rpr. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-0551-8, ISBN 978-0-8047-0551-6. pp. 83–91.

81. Ernest Young, "Politics in the Aftermath of Revolution," in John King Fairbank, ed., The Cambridge History of China: Republican China 1912–1949, Part 1 (Cambridge University Press, 1983; ISBN 0-521-23541-3, ISBN 978-0-521-23541-9), p. 228.

82. Altman, Albert A., and Harold Z. Schiffrin. “Sun Yat-Sen and the Japanese: 1914–16.” Modern Asian Studies, vol. 6, no. 4, 1972, pp. 385–400. JSTOR,

http://www.jstor.org/stable/31153983. South China morning post. Sun Yat-sen's durable and malleable legacy. 26 April 2011.

84. South China morning post. 1913–1922. 9 November 2003.

85. Bergère & Lloyd: 273

86. Kirby, William C. [2000] (2000). State and economy in republican China: a handbook for scholars, volume 1. Harvard publishing. ISBN 0-674-00368-3, ISBN 978-0-674-00368-2. pg 59.

87. Robert Payne (2008). Mao Tse-tung: Ruler of Red China. READ BOOKS. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4437-2521-7. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

88. Great Soviet Encyclopedia. 1980. p. 237. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

89. Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov (1982). Great Soviet encyclopedia, Volume 25. Macmillan. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

90. Bernice A Verbyla (2010). Aunt Mae's China. Xulon Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-60957-456-7. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

91. Gao. James Zheng. [2009] (2009). Historical dictionary of modern China (1800–1949). Scarecrow press. ISBN 0-8108-4930-5, ISBN 978-0-8108-4930-3. pg 251.

92. Spence, Jonathan D. [1990] (1990). The search for modern China. WW Norton & company publishing. ISBN 0-393-30780-8, ISBN 978-0-393-30780-1. Pg 345.

93. Ji, Zhaojin. [2003] (2003). A history of modern Shanghai banking: the rise and decline of China's finance capitalism. M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 0-7656-1003-5, ISBN 978-0-7656-1003-4. pg 165.

94. Ho, Virgil K.Y. [2005] (2005). Understanding Canton: Rethinking Popular Culture in the Republican Period. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-928271-4

95. Carroll, John Mark. Edge of Empires:Chinese Elites and British Colonials in Hong Kong. Harvard university press. ISBN 0-674-01701-3

96. Ma Yuxin [2010] (2010). Women journalists and feminism in China, 1898–1937. Cambria Press. ISBN 1-60497-660-8, ISBN 978-1-60497-660-1. p. 156.

97. 马福祥,临夏回族自治州马福祥,马福祥介绍---走遍中国.

http://www.elycn.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

98. Calder, Kent; Ye, Min [2010] (2010). The Making of Northeast Asia. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-6922-2, ISBN 978-0-8047-6922-8.

99. Barth, Rolf F.; Chen, Jie (1 January 2016). "What did Sun Yat-sen really die of? A re-assessment of his illness and the cause of his death". Chinese Journal of Cancer. 35 (1): 81. doi:10.1186/s40880-016-0144-9. ISSN 1944-446X. PMC 5009495. PMID 27586157.

100. "Dr. Sun Yat-sen Dies in Peking". The New York Times. 12 March 1925. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

101. "Lost Leader". Time. 23 March 1925. Retrieved 3 August 2008. A year ago his death was prematurely announced; but it was not until last January that he was taken to the Rockefeller Hospital at Peking and declared to be in the advanced stages of cancer of the liver.

102. Sharman, L. (1968) [1934]. Sun Yat-sen: His life and times. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 305–306, 310.

103. Bullock, M.B. (2011). The oil prince's legacy: Rockefeller philanthropy in China. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8047-7688-2.

104. Leinwand, Gerald (9 September 2002). 1927: High Tide of the 1920s. Basic Books. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-56858-245-0. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

105. 國父遺囑 [Founding Father's Will]. Vincent's Calligraphy. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

106. "Cancer Communications". Retrieved 10 July 2018.

107. "Clinical record copies from the Peking Union Medical College Hospital decrypt the real cause of death of Sun Yat-sen". Nanfang Daily (in Chinese). 11 November 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

108. Uradyn Erden Bulag (2002). Dilemmas The Mongols at China's edge: history and the politics of national unity. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 51. ISBN 0-7425-1144-8. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

109. Stéphane A. Dudoignon; Hisao Komatsu; Yasushi Kosugi (2006). Intellectuals in the modern Islamic world: transmission, transformation, communication. Taylor & Francis. p. 134; 375. ISBN 978-0-415-36835-3. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

110. Rosecrance, Richard N. Stein, Arthur A. [2006] (2006). No more states?: globalization, national self-determination, and terrorism.Rowman & Littlefield publishing. ISBN 0-7425-3944-X, 9780742539440. pg 269.

111. Lorenz Gonschor, "Revisiting the Hawaiian Influence on the Political Thought of Sun Yat-sen." Journal of Pacific History 52.1 (2017): 52–67.

112. Eric Helleiner, "Sun Yat-sen as a Pioneer of International Development." History of Political Economy 50.S1 (2018): 76–93.

113. Stephen Shen, and Robert Payne, Sun Yat-Sen: A Portrait (1946) p 182

114. 孫中山學術研究資訊網 – 國父的家世與求學 [Dr. Sun Yat-sen's family background and schooling]. [sun.yatsen.gov.tw/ sun.yatsen.gov.tw (in Chinese). 16 November 2005. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 2 October2011.

115. "Sun Yat-sen's descendant wants to see unified China". News.xinhuanet.com. 11 September 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

116. "Tripping Cyborgs and Organ Farms: The Fictions of Cordwainer Smith | NeuroTribes". NeuroTribes. 21 September 2010. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

117. "Antong Cafe, The Oldest Coffee Mill in Malaysia". Archived from the original on 12 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January2018.

118. Isaac F. Marcosson, Turbulent Years (1938), p.249

119. Guy, Nancy. [2005] (2005). Peking Opera and Politics in Taiwan. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02973-9. pg 67.

120. "Sun Yet Sen Penang Base – News 17". Sunyatsenpenang.com. 19 November 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2011.[dead link]

121. "Sun Yat-sen's US birth certificate to be shown". Taipei Times. 2 October 2011. p. 3. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

122. "Google Maps". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

123. "Queens Campus".

http://www.youvisit.com. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

124. "City to Dedicate Statue and Rename Park to Honor Dr. Sun Yat-Sen". The City and County of Honolulu. 12 November 2007. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

125. "Sun Yat-sen". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

126. "St. Mary's Square in San Francisco Chinatown – The largest chinatown outside of Asia". Retrieved 6 December 2015.

127. "Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne".

http://www.cysm.org. Chinese Youth Society of Melbourne. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

128. "Char Asian-Pacific Study Room". Library.kcc.hawaii.edu. 23 June 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

129. "Mars Exploration Rover Mission: Press Release Images: Spirit". Marsrover.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

130. "Opera Dr Sun Yat-sen to stage in Hong Kong". News.xinhuanet.com. 7 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

131. Gerard Raymond, "Between East and West: An Interview with David Henry Hwang" on slantmagazine.com, 28 October 2011

132. "Commemoration of 1911 Revolution mounting in China". News.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

133. "Space: Above and Beyond s01e22 Episode Script SS".

http://www.springfieldspringfield.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

134. 《斜路黃花》向革命者致意 (in Chinese). Takungpao.com. Retrieved 12 October 2011.[dead link]

135. 元智大學管理學院 (in Chinese). Cm.yzu.edu.tw. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

136. Kenneth Tan (3 October 2011). "Granddaughter of Sun Yat-Sen accuses China of distorting his legacy". Shanghaiist. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

137. 国父孙女轰中共扭曲三民主义愚民_多维新闻网 (in Chinese). China.dwnews.com. 1 October 2011. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

138. "Archived copy" 人民网—孙中山遭辱骂 "台独"想搞"台湾国父". People's Daily. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

139. Chiu Hei-yuan (5 October 2011). "History should be based on facts". Taipei Times. p. 8.

Further reading• Bergère, Marie-Claire (2000). Sun Yat-sen. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4011-9. online free to borrow

• Pearl S. Buck, The Man Who Changed China: The Story of Sun Yat-sen (1953)

• D'Elia, Paschal M. Sun Yat-sen. His Life and Its Meaning, a Critical Biography (1936)

• Du, Yue. "Sun Yat-sen as Guofu: Competition over Nationalist Party Orthodoxy in the Second Sino-Japanese War." Modern China 45.2 (2019): 201–235.

• Kayloe, Tjio. The Unfinished Revolution: Sun Yat-Sen and the Struggle for Modern China (2017). excerpt

• Khoo, Salma Nasution. Sun Yat Sen in Penang (Areca Books, 2008).

• Lee, Lai To, and Hock Guan Lee, eds. (2011). Sun Yat-Sen, Nanyang and the 1911 Revolution. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789814345460.

• Linebarger, Paul M.A. Sun Yat Sen And The Chinese Republic (1925) online free

• Linebarger, Paul M.A. Political Doctrines Of Sun Yat-sen (1937) online free

• Martin, Bernard. Sun Yat-sen's vision for China (1966)

• Restarick, Henry B., Sun Yat-sen, Liberator of China. (Yale UP, 1931)

• Schiffrin, Harold Z. Sun Yat-sen: Reluctant Revolutionary (1980)

• Schiffrin, Harold Z. Sun Yat-sen and the origins of the Chinese revolution (1968).

• Shen, Stephen and Robert Payne. Sun Yat-Sen: A Portrait (1946) online free

• Soong, Irma Tam. "Sun Yat-sen's Christian Schooling in Hawai'i." The Hawaiian Journal of History, vol. 31 (1997) online

• Wilbur, Clarence Martin. Sun Yat-sen, frustrated patriot (Columbia University Press, 1976), a major scholarly biography

• Yu, George T. "The 1911 Revolution: Past, Present, and Future," Asian Survey, 31#10 (1991), pp. 895–904, online historiography

External links• "Sun Yat Sen Nanyang memorial hall". Retrieved 7 May 2015.

• "Doctor Sun Yat Sen memorial hall". Archived from the original on 29 August 2005. Retrieved 1 July 2005.

• ROC Government Biography (in English and Chinese)

• Sun Yat-sen in Hong Kong University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives

• Contemporary views of Sun among overseas Chinese

• Yokohama Overseas Chinese School established by Dr. Sun Yat-sen

• National Dr. Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall Official Website (in English and Chinese)

• Homer Lea Research Center

• Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Foundation of Hawaii A virtual library on Dr. Sun in Hawaii including sources for six visits

• Who is Homer Lea? Sun's best friend. He trained Chinese soldiers and prepared the frame work for the 1911 Chinese Revolution.

• Works by Sun Yat-sen at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Sun Yat-sen at Internet Archive

• Funeral procession for Sun Yat-sen in Chinatown, Los Angeles at the Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.