Ouyang Jingwu: a Biography, Excerpt from "Differentiating the Pearl From the Fish Eye: Ouyang Jingwu (1871-1943) and the Revival of Scholastic Buddhism"

A dissertation presented by Eyal Aviv

to The Committee on the Study of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of The Study of Religion Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts

July, 2008

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

2.2 Ouyang Jingwu: a Biography

2.2.1 Phases in Ouyang’s career

Below is an outline of the major phases in Ouyang’s career, which are described in greater detail in the rest of this chapter. Drawing on the analysis of Cheng Gongrang, 26 I have divided the career of Ouyang into three main phases, which are further divided into subphases:

1. Early phase – Confucian education. 1877-1901

a. Traditional Education [between 1877 and 1894] -- Ouyang focused mainly on Chengzhu School of thought and still aspired to an official career.

b. The Discovery of the Luwang School [1894-1901] -- During the Sino-Japanese war of 1894 Ouyang decided that Chengzhu thought, which was the state ideology in China would neither help his personal quest “for the meaning of life and death” nor to save China. He turned then to the competing Luwang School of thought. This phase ended in 1901, when he was introduced to Buddhism.

2. Adulthood – The Buddhist phase subdivided into three stages [1901-1931]

a. First Steps into Buddhism [1901-1904] -– in 1901 Ouyang was introduced to Buddhism by Gui Bohua, a friend who studied under Ouyang’s future teacher Yang Wenhui. Gui introduced Ouyang to the Buddhist thought of Yang Wenhui’s circles, which Ouyang characterized later as “[a group that] study Huayan and venerate the Awakening of Faith.”

b. Yang Wenhui’s protégé [1904-1911] -- In 1904 Ouyang traveled to Nanjing to meet Yang Wenhui for the first time. In the period between their first meeting and Yang’s death Ouyang studied under Yang Wenhui and thoroughly investigated the different schools of Chinese Buddhism. At this stage, although he still found the Huayan-Awakening of Faith position to be the core of Buddhism, he gradually made further research into the teaching of the Weishi School and became known in Yang Wenhui’s circle as the Weishi specialist.

c. The Yogacara/Weishi phase and failed institutional reforms [1911-1923] -– after Yang Wenhui’s death in 1911, Ouyang turned his attention to reforms within Buddhism. In a few provocative and bold steps he tried to undermine monastic authority and establish an overarching association, which would oversee all Buddhist institutions. This radical move met a vehement monastic response, which led to the establishment of a new institution, “The Buddhist Association of China” led by monks. This new institution along with the failure of his own association shifted Ouyang’s focus to the realm of ideas and Buddhist education, where he was destined to make his most important contribution.

d. Harmonizing Yogacara with Prajñaparamita thought [1923-1931] -- In 1923 Ouyang lost his second son and two of his favorite students, Xu Yiming and Huang Shuyuan. Grieving over his multiple tragedies he made a vow to propagate Prajnaparamita thought. This vow was the beginning of his attempts to synthesize Prajnaparamita and Yogacara thought. At a conference that year Ouyang remarked: “For a long while now we who studied together exchanged views over the Faxiang teaching and we can say that we have already kindled some light of understanding. I wish now that you will explore the secrets of the Prajnaparamita and turn [this light] into a torch of wisdom.” He instructed his students that in addition to a thorough learning of Yogacara they must probe into the true characteristics of “Nagarjuna studies” as well. In 1928 Ouyang wrote a preface to the MahaPrajnaparamita Sutra in which he brought to completion his attempts to harmonize Yogacara with Madhyamaka thought.

3. Returning home, Ouyang’s late thought [1931-1943]

a. In the later stages his of his life Ouyang rediscovered Huayan thought and studied the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, texts and approaches, which he repudiated in his early career. In this final phase of his career he tried to harmonize his earlier thought with these new emphases. This led to the creation of his own panjiao system (a doxographical method which he had criticized in the past but found useful toward the end of his life.)

b. In his later years he also made a surprising return to Confucianism. Using the same syncretic approach, Ouyang tried to synthesize Buddhism and Confucianism, arguing that they are essentially the same and that they “return to the same source” (78). Around 1931, when Ouyang turned 60, he attempted a systematization of the Confucian canon and teachings modeled after his experience with Buddhist teachings. This attempt was intensified after he moved to Sichuan in 1937 and continued up until his death in 1943. Ouyang thought that, since they share the same principles, the current strength of Buddhism could help restore Confucianism. He remarked then, “Alas, Confucianism is dying. If we will get down to the essence of the Buddhist canon and refined prajna we will be able to revive the state of Jin by means of the State of Qin27 [and] the Dao of King Wen and King Wu will not crumble.”

2.3 Ouyang’s biography in detail

2.3.1 Early Years

2.3.1.1 Family Background

In 1936, when Ouyang was sixty-six he wrote to his uncle:

My study of Buddhism is different from others; you, my uncle, are familiar with the hardships that my mother experienced. Confucianism offered no answers to my inquiries into matters of sickness and life and death. As to the end-point, where [cultivation] and the ultimate converges, and as to the starting-point, where one takes up cultivation, I still felt as perplexed and remained uncertain. Hence, after my mother passed away, I cut off reputation, wealth, and attachment to food and sex. I set foot on the sramana path and turned to teachers and friends to ask about that path, and yet my wish was difficult to fulfill. After thirty years of study, and searching for answers among all the ancient sages from the West (i.e. Indian Buddhist teachers), [Buddhism] touched my heart and enlightened me. [Meanwhile] tragedies [haunted] my family. My daughter, Ouaygn Lan, studied with me in Nanjing. When I returned from Gansu, where I had gone on printery business, I learned that she had passed away. I howled and lamented deep into the nights, but there was nothing I could do about [her death]. Then, I made a determined effort to read [Buddhist] scriptures, often until dawn. As a consequence, I understood the meaning of the Yogacarabhumi and was enlightened to the meaning of consciousness-only (weishi, Chinese). This was why I made the trip to Yunnan, where scholars gathered daily from all directions [to study with me]. [At that time], my son Zhanyuan, an exceptional talent with high ideals, drowned while taking a swim. I was determined then to study the Prajnaparamita literature, the Huayan sutra, and the Nirvana Sutra. I then understood them one after the other. Gradually, I arrived to my current mastery of the material, where for the first time, everything is clear. [On this basis], I have come up with the definitive understanding [of the Buddhist doctrines] (Chinese) 28

This passage summarized major events that shaped Ouyang’s intellectual trajectory. As can be seen from the quote, Ouyang’s biography is closely connected to developments and changes in his thought. These vicissitudes serve as a reminder that as intellectual historians we have to be sensitive to changes and continuations in the thought of the individuals we study. In Ouyang’s thought we see that although Ouyang was mostly famous for his study of the Yogacara tradition (the phase on which this dissertation focuses) it would be a mistake to reduce him to merely a Yogacarin. In many ways, each phase has its own, slightly different, “Ouyang Jingwu.”

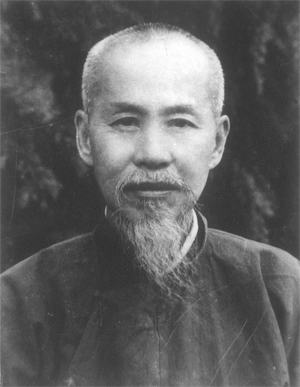

Ouyang Jingwu was born as Ouyang Jian (Chinese), courtesy name Ouyang Jinghu (Chinese), on October 8th 1871, in Yihuang County (Chinese), Jiangxi province. He changed his name to Ouyang Jingwu when he was in his early 50’s.

Ouyang’s ancestors were peasants. The family became known only with Ouyang Jingwu’s paternal great-grandfather, Ouyang Wenkai (Chinese, ??-1855). Wenkai did not achieve success through the imperial exams but he was a man of letters, whose poems, painting and calligraphy were known to his contemporaries. 29 The real breakthrough in the family fortune happened in the time of Wenkai’s son, Ouyang Dingxun, who passed the imperial exams at the provincial level (Chinese). After his success in the provincial examination, Ouyang Dingxun passed the imperial exams in the capital and received a teaching position at the Jingshan Imperial School. He was the first from Yihuang County to enter this path of civil service. Dingxun’s promising career was brought to an abrupt end when his father died. Upon hearing the news, Dingxun started his journey back home but it is said that he died of sorrow during the journey.

Dingxun had three children (one of them was in fact his nephew who was raised as part of the family). His oldest son, Ouyang Hui (Chinese, 1822-1876), was Ouyang Jingwu’s father. Ouyang Hui had passed the provincial exam (Chinese), lived in the capital for 20 years and, like his father and grandfather, made a name for himself as a calligrapher and as a man of letters. Despite his relative success he continuously failed to pass the national imperial exam.

The mid-nineteenth century in China was turbulent, and rebellions broke out in several places, many of which were violent and damaged the effective rule of the Qing Imperial house. But none was as devastating and bloody as the Taiping rebellion (1851-1864) The Taiping armies exposed the ineffectiveness of the Qing banners armies. The Qing rulers had to support a new form of armed forces, which helped save the dynasty, the local militias, which helped save the dynasty. Ouyang Hui, who by that time had given up the ideal of passing the national exam, returned to Jiangxi and helped build the local militia there.

2.3.1.2 Death of his father and its aftermath

Despite Ouyang Hui’s reputation and his achievement as a juren, life in the Ouyang’s household was never free of economic strain. Since Dingxun could not make ends meet, Ouyang Hui had to support his parents in addition to his own household. He found a job at the local government in Jiangsu but died shortly after in 1876.

Ouyang Jingwu’s mother was one of Ouyang Hui’s three wives. Her surname was Wang (Chinese) and she came from a village in the vicinity of Guiyang in Guizhou province. She gave birth to one son and two daughters, one of whom died young. When Ouyang Hui died in 1876, Ouyang Jingwu was only 5; suddenly the household of 8 people had no support. As a result Ouyang’s family sank deeper into poverty. Shortly after the passing of his father, his uncle Ouyang Xuan died too. Left with no other choice, the whole extended family had to rely on Ouyang Yu (Chinese, 1837- 1904), the cousin of Ouyang Hui. It was Ouyang Yu who was responsible for most of Ouyang’s early education.

Ouyang Yu passed the bagong exams (Chinese) 30 and later also the imperial exams and earned a second rank in the court exams. But, being dissatisfied with the job he was assigned to, he was not interested serving in the imperial bureaucracy and instead he devoted himself to studying. Since he gave up his official career, his family economic situation continued to be dire. In addition to his family, Ouyang Yu had to support the families of his two cousins who died prematurely (i.e. Ouyang Dingxun’s sons). His income came from tutoring children of the nobility.

2.3.1.3 Early Education

Ouyang Yu, who was responsible for Ouyang Jingwu’s early education, was a traditional thinker, and was hostile to the modern trends in his intellectual environment, resulting from the encounter with the West. Specifically, Ouyang Yu was very critical of the New Text movement and their interest in the Gongyang commentary.31 Politically, He opposed the 100 days reform movement of Kang Youwei and Liang Qichao.

After the death of Ouyang Yu, Ouyang Jingwu wrote about how he first set his mind on education, “My brother Huang gave up his studies at a very young age. My uncle shed tears and tried to talk him out of it. He beat him with a stick and cried about my father. Once he gave me a book and said, ‘Your father taught me this book, and today I give it to you’. I opened it and looked at it. Despite not understanding a word of it I was deeply moved.”32 In the following years Ouyang stayed close to his uncle throughout his journey to find new jobs, and despite the constant economic pressure, he never gave up studying or contemplated returning to the peasantry.

For young Jingwu, Ouyang Yu was more than a teacher or a mentor; he was the father figure that he had lost when he was just a child. Ouyang’s affection and gratitude toward his uncle was felt throughout his life.33 His uncle remained his role model even when he later renounced Confucianism and moved away from his teachings.

The education Ouyang Jingwu received from his uncle was broad and encompassed most of the traditional branches of knowledge that were supposed to prepare a young scholar for a path of scholarship and service. According to Wang Enyang, who was Ouyang’s student, after basic writing and reading skills, Ouyang Yu taught Jingwu the art of writing poetry and prose. Later he introduced young Ouyang Jingwu to the philological method of scholarship of the Han Studies movement. After that Ouyang Yu turned to the traditional foci of classical education, the philosophy of the Chengzhu school of Confucianism.34

Indeed, according to Gong Jun, one way to understand Ouyang’s thought is as a result of this tension between the more metaphysical teaching of the Chengzhu branch and the more scholastic methods of the evidential research movement.35 For Gong Jun, the tension between his scholastic tendencies and his normative search for the existence of moral order is also a reflection of the tension between the traditional and modern strands of thought in his lifetime.

Gong Jun’s point is valuable for our general understanding of Ouyang. Ouyang was not only the iconoclast thinker that he is remembered as. In his career and character he encompassed complexities that include both his genuine Buddhist beliefs and critical scholarship. This of course should not surprise anyone who understands Ouyang to be a scholastic Buddhist or as he might be called today a “Buddhist theologian” rather than a scholar of Buddhism in the Western academic sense of the word.

2.3.1.4 A full cup of duhkha: experiences of losses in early life

Ouyang experienced human transience early in his life. Those experiences, and his failure to find answers for the vulnerablility of human life in the Confucian tradition, were part of the reasons that led him eventually to Buddhism. His first encounter with death, as stated above, was the loss of his father when he was 5, but that was only the beginning. Ouyang outlived his entire family, and witnessed the death of his parents, siblings, wife and all of his children. Ouyang’s father had 3 wives; each gave birth to 3 children. Of his nine brothers and sisters, 4 died as children, among them Zhaodi who was his sister from of his mother. His children -- two sons, Ouyang Ge (1895-1940) and Ouyang Dong (1905-1923) and one daughter, Ouyang Lan (1899-1915) -- all died prematurely in tragic circumstances.

Intellectuals in the modern period China were in constant search for answers for the national crisis that had swept China since the nineteenth century, and Ouyang was no exception. But at the same time we must not forget the personal despair and tragic circumstances of Ouyang life, for many of the reasons for his intellectual choices were impacted by personal events of his biography as much as they were influenced by large events on a national scale.

2.3.2 Embarking on an Independent Path

2.3.2.1 Jingshun Academy and the meeting with Gui Bohua

In 1890, when Ouyang was nineteen years old he was admitted into Jingxun Academy (Chinese) in Jiangxi’s capital, Nanchang. Jingxun academy was one of the three major institutions for higher learning in Nanchang in those days. While the major emphasis of the school was on traditional learning of the Confucian canon and the dynastic histories, the school also taught Western studies, the importance of which became more and more evident in late Qing China. Moving from a small town to the capital of the province was the first opportunity for Ouyang to expand his horizons beyond the boundaries of the traditional education of his uncle. It was here for the first time that he learned about indigenous unorthodox views and the novel ideas coming from the West.

Beyond the exposure to cutting edge innovations in academic studies of those days, 36 another contribution of the Jingxun Academy period was his meeting with Gui Bohua (Chinese, 1861-1915),37 who was destined to have a far reaching impact on Ouyang’s development. Ouyang and Gui Bohua developed a strong friendship. Gui Bohua, who was 10 years older than Ouyang, exposed the young student from Yihuang County to new intellectual horizons and eventually to Buddhism.

2.3.2.2 The Sino-Japanese war and Ouyang’s conversion to Luwang thought

While Ouyang studied in the Jingshu Academy, China suffered one of its most traumatic defeats in the history of the Qing, the 1895 Sino-Japanese War, with the humiliating Shimonoseki treaty38 that followed.39 Where was Ouyang during all those dramatic developments? Despite the fact that he sympathized with the reform movement and despite the fact that, like other young intellectuals, he was shocked by the defeat in the war and its outcome, Ouyang did not actively participate in the movement. In 1895, he left Nanchang and returned to Yihuang to get married, and then stayed there to support his mother.

Ouyang deeply sympathized with the cause of the reform, but nonetheless, his reaction to the defeat was different from that of his more politically active friends, and was more intellectual in nature. Lü Cheng recalled, “The war in the East has already been conducted and the affairs of the state deteriorated day by day. The master indignantly saw miscellaneous studies40 as unhelpful, and focused on the Luwang School’s teaching as a possible remedy to the social problem of the day.”41 During these years he diligently studied Wang Yangming thought before his gradual conversion to Buddhism. It took a few years of self-study and discussion with close friends to make this shift happen.

2.3.2.3 Gradual Embracing of Buddhism – Gui Bohua’s impact

On September 21, 1898, the conservative faction of the imperial house, led by Cixi forced the emperor Guangxu into house arrest and crushed the reform movement. The failure of the reform movement had a devastating impact on Gui Bohua. Ouyang, in his biographical account of Gui Bohua writes, “After the death of the six martyrs42 and the arrests made among the ‘Kang [Youwei] Party’ Bohua hid in his village. Because of the cold winter he was sick with malaria and was lying in his bed in the middle of the night with one candle. He received a copy of the Diamond sutra, which he constantly read and which awakened him suddenly to the illusory nature of human life. Upon his recovery he went to Jinling [printery] and studied Buddhism under Yang Renshan (i.e. Yang Wenhui). It was another turn in [Bohua’s] studies.”43

Despite the fact that Ouyang did not follow Gui Bohua right away he could not stay detached from the changes his close friend went through. One time, Ouyang invited Gui Bohua to visit him at his hometown. When Gui Bohua arrived, they debated Buddhism and Wang Yangming thought, but Ouyang was not an easy convert. Despite Gui Bohua’s skills in argument, Ouyang had an excellent background in philosophical and textual studies that he had received from his uncle and in the academy. After a long and heated debate he was not persuaded. Before Gui Bohua left he made a last attempt. Ouyang relates, “He gave me copies of the Awakening of Faith and the Suramgama sutra, and said, ‘How about that for the time being, you take these and put them next to your bed? Make them your bedtime reading?’ I did not feel like taking them.”44

However, despite his reluctance, perhaps out of respect to his friend, Ouyang took the books. These two texts, which were the foci of study in Wang Wenhui’s circle, were the gateway through which Ouyang encountered Buddhism for the first time.

In addition to his commitment to and interest in the teachings of the Luwang School of Neo-Confucianism, Ouyang had another reason for which he was reluctant to embrace Buddhism. In 1897, his brother, Ouyang Huang died, and he was left the only remaining support for his family. In order to be able to earn money as a scholar, he had to tread in the path of his ancestors and take the imperial examinations. Like many other young intellectuals in the end of the Qing dynasty, Ouyang was not interested in taking the imperial exams, but the death of his elder brother and family responsibility changed his plans.

In 1904, Ouyang passed the prefecture exam but achieved only the second rank (Chinese). While those who achieve the first rank went to elite national schools (Chinese) those in the second rank often obtained minor official positions. Ouyang became an instructor in Guangchang, Jiangxi province. Since the examination system was abolished a year later. Ouyang never tried the juren exam.

Shortly after Gui Bohua’s visit to Ouyang’s hometown, Ouyang did read the two scriptures that Gui Bohua gave him. He was gradually influenced by the religiosity and the enthusiasm of Gui Bohua but at the same time he kept both feet in the Confucian world. It was a tradition in which he felt at home, a tradition that promised success and work, and one that would fulfill the destiny of his ancestors, who strove to serve the court through the official path.

2.3.2.4 Ouyang and Yang Wenhui

In addition to the two scriptures given to him, Gui Bohua also told Ouyang about his teacher, Yang Wenhui (Chinese 1837-1911). Yang Wenhui is considered to be “the father of the [Buddhist] revival,”45 and taught Buddhism to many prominent intellectuals of Ouyang’s day.46 Toward the end of the nineteenth century, Yang Wenhui established himself as an authoritative figure on Buddhism. Monks and lay people came to study under him. He is well known for his contribution to the spread of the dharma, especially through printing and teaching. In 1866, the destruction Buddhism suffered after the Taiping Rebellion (1851-1864) prompted Yang Wenhui, with a help of likeminded friends, to open the Jinling Sutra Printery (Chinese). The Jinling printery was located in Nanjing (and still is today), where many intellectuals came to study Buddhism under Yang’s guidance. Despite the fact that Ouyang knew of Yang Wenhui and developed an interest in Buddhism, it took him a few more years before he met him for the first time in 1904.

Lü Cheng recounts that after passing the imperial exams, Ouyang, on the way back from Beijing to his native Yihuang, stopped in Nanjing to visit his friend, Gui Bohua, who studied with Yang Wenhui at that time. Gui Bohua introduced Ouyang to Yang Wenhui, and the latter preached to Ouyang. After the meeting, Ouyang’s faith in Buddhism “was increased and solidified.”47 But Ouyang still was not entirely persuaded. In addition, as a loyal son, as long as his mother was still alive, he could not turn his back on his father’s heritage and embrace Buddhism. Cheng Gongrang notes that there are no concrete details about the actual content of the meeting, but he plausibly speculates that part of the conversation revolved around the different teachings of the Awakening of Faith and Wang Yangming thought, and that this question was resolved to Ouyang’s satisfaction.48 In 1905, Gui Bohua left to study in Japan, and Ouyang took on an instructor position. During this time he devoted himself to the study Buddhism, with a critical approach, but now more sympathetic.

Toward the end of his life, especially after his years in London, Yang Wenhui promoted a “return to ancient Buddhism” which for him meant, among other things, the Yogacara tradition. In their 1904 meeting, Yang urged Ouyang to study the vijnaptimatra49 tradition. For Ouyang this was to be the gateway through which he was able to fully convert to Buddhism. Yogacara eventually gave him the answers that he was looking for and which he failed to find in the Awakening of Faith. Despite the fact that he overcame his intellectual doubts, the commitment to the family’s heritage still prevented him from fully embracing Buddhism.

This last condition changed in the following year, and the event dramatically altered Ouyang’s life. In February 13, 1906, Ouyang’s mother passed away. Ouyang, who was very close to her, grieved deeply, and Lü Cheng tells us that as a result Ouyang decided to “refrain from meat and sex, stop his official career, put his trust in the Buddhadharma and strive for unsurpassed awakening.”50 After their mother’s death, Ouyang’s beloved sister who lived with his mother and served as a tutor to Ouyang’s children moved to live in a Buddhist monastery as well.

In 1907, Ouyang visited Yang Wenhui in Nanjing for the second time and spent some months there. Later in the same year, he left together with his cousin Ouyang Yi to study in Japan. Ouyang lived together with Gui Bohua in Tokyo. In Tokyo he met Kuai Ruomu (Chinese) who was one of Yang Wenhui’s disciples, and later became a government official; Kwai was to donated money to help Ouyang establish his Inner Studies Institute. Beyond these details we know little about Ouyang’s time in Japan.

In the autumn of 1908, Ouyang returned to China. Initially, he taught at Guangdong and Guangxi but he had to resign due to sickness and returned home. After his recovery, Ouyang decided to become a scholar recluse living as a peasant off the land. He moved with his Jingxuan academy classmate Li Zhengang to Jiufeng Mountain in the vicinity of Yihuang. This happy phase in Ouyang’s life did not last long. Soon the cold weather on the mountain took its toll on Ouyang’s health and he had to give this life up. Upon his recovery Ouyang decided to concentrate instead on Buddhism, and to do so in the most effective way he had to return to Yang Wenhui in Nanjing.

In 1908, Yang Wenhui was busy establishing a higher learning Buddhist Studies institute, which he called the Jetavana Vihara Academy (Chinese). 51 The institution was short lived and was closed in 1909 because of financial difficulties. Instead, In 1910 Yang Wenhui established a Buddhist Research Association with some like-minded intellectuals. Their intention was to promote a new style of lay Buddhism, which was critical of the Chan Buddhists dismissive approach toward the Buddhist scriptures. Sharing Yang’s criticism of Chan, Ouyang joined Yang Wenhui and participated in the Research Association’s activities. The Research Association later became the model for his own Inner Studies Institute.

Ouyang’s determination to turn his back on his former life and stay with Yang Wenhui came a little too late. Yang Wenhui died a year later in 1911, and his death marks the beginning of arguably the most important stage of Ouyang’s life; the phase of establishing himself as a Buddhist thinker, an educator of a new generation of intellectuals and of a promoter of Buddhist teaching that he helped to revive in China - the Yogacara teaching.

2.3.2.5 The Death of Yang Wenhui

Yang Wenhui died on August 17, 1911 surrounded by his family and his close disciples Kuai Ruomu, Mei Guangxi and Ouyang Jingwu. It was just two days before the revolution began in Wuhan, a revolution that would bring the Imperial era to an end. In his will, Yang Wenhui left the business of publishing sutras, which was his most salient contribution to Modern Buddhism, to Ouyang Jingwu. Ouyang recounted the incident, “When the master left for the West52 he entrusted the [publishing business] to me and said ‘You will come to my assembly and I will go to yours,53 [for now] I am entrusting in your hands the continuation of the engraving of the scriptures’, humbled, I bowed my head and respectfully accepted his will.”54

It is interesting to ask why it was Ouyang Jingwu who received this honor. After all, Yang Wenhui had so many disciples, many of whom studied with him longer than Ouyang. One plausible answer is that Ouyang came to Yang after he decided to dedicate his life to the study Buddhism. Based on their previous encounters Yang was already familiar with Ouyang’s philological and philosophical skills, and his critical and careful research method. He therefore probably saw Ouyang as a suitable candidate to continue the propagation of Buddhism in this new era.55

Yang Wenhui’s will was an attempt to balance Jinling printery’s needs with those of his family. The Jinling printery’s money and buildings were to be designated as a public domain, and would not go to the family. In addition, to ensure the continuation of the Jinling printery’s work, Yang divided his responsibilities among three of his disciples, Chen Xian, who was responsible for the management; Chen Yifu who was responsible for public relations and Ouyang Jingwu who was responsible for publishing and academic matters. Yang Wenhui also left clear instructions for Ouyang. First and foremost, Ouyang was to finish and publish the remaining 50 fascicles of the Yogacarabhumi-sastra, a task which Yang did not finish in his lifetime,56 he was also to publish Yang Wenhui’s Commentary on the Explanation of Mahayana-sastra [Chinese] and his Miscellaneous Records of Contemplations on the Equality and Non-Equality of Things [Chinese]. Finally, Yang asked Ouyang to publish an Outline of the Buddhist canon, which would make accessible the whole range of texts that existed in the canon and that they were being engraved in the printery.

2.3.3 Carving his own path

After the death of Yang Wenhui, Ouyang felt that he and his friends shared a great responsibility for continuing the revival of Buddhism in China. However, Chen Xian passed away in 1918, and Chen Yifu resigned shortly after. These new developments left the way open for Ouyang to take over the lead of the Jinling printery, and run the place according to his own vision. Like Yang Wenhui before him, Ouyang had to establish his own reputation in order to secure funds to sustain the Jinling printery and its activities. In the following years, Ouyang dedicated himself to achieving these difficult tasks.

The laity in China has always supported Buddhist activities, but funds went only to monastic institutions. The idea that the laity might support another layperson’s institute, which would be dedicated to learning, was hard to promote among traditional Buddhist supporters.57 Since Ouyang came from a scholarly background, and since he despised “superstitious” laypeople and “ignorant” monks, his natural course of action was to turn to influential and educated people, who appreciated learning and saw merit in advancing Buddhist studies in China. But in order to convince anyone to donate money to his cause, he had to establish himself as an authoritative figure. His first attempt was in the public arena.

2.3.3.1 The failure of the first Buddhist Association

In the March of 1912, Ouyang made his first attempt to build his reputation among fellow Buddhists. He and some of his friends petitioned to the newly established government in Beijing, which was headed by Sun Yat-sen, to unite the entire Buddhist institution under a Buddhist Association. This ambitious and controversial proposal came at a time of insecurity for the Sangha and its Buddhist property. While the Imperial regime traditionally protected and supported Buddhism, the new government was far less committed. As a result, Buddhists in the early ROC found themselves facing growing threats to their institution by progressive forces, greedy officials, bandits and warlords.

In order to face Buddhist adversaries’ criticism and effectively preserve their property, Buddhists responded in a few different ways: They turned to rich and powerful lay Buddhists to make up for the lack of patronage from the central regime. They made attempts to reform their education system and adapt it to the demands of the new “modern” age. In addition, they searched for ways to unify the different Buddhist institutions under one Buddhist association, which would be able to coordinate Buddhist actions and reforms.

Ouyang’s association,58 which was proposed in March 1912, was the pioneering institute. Later, throughout the Republican era, many associations were established only to be dismantled soon after. The decision to establish the Chinese Buddhist Association [Chinese] in Nanjing was followed by the petition to Sun Yat-sen mentioned above. Its bold charter, which Holes Welch dubbed “astonishing,”59 set forth the group’s hope to supervise the entire Buddhist Sangha, lay and monastic. Since it is instructive and gives a vivid picture of Ouyang’s ambitions at that stage, I will quote the charter in full.

The Association shall have the right to superintend all properties belonging to all Buddhist organizations.

The Association shall have the right to reorganize and promote all Buddhist business affairs.

The Association will have the right to arbitrate disputes that may arise between Buddhists and to maintain order among them.

The Association shall have the right to require the assistance of the National Government in carrying out all the social, missionary, and philanthropic works stated above.

All activities of the Association within the scope of the law shall not be interfered with by the Government.

The National Government is requested to insert a special article in the Constitution to protect the Association after it has been acknowledged as a lawful organization60

Welch commented, “Here was something far more dangerous than the invasion of Jinshan61 – a plan to place the whole Buddhist establishment in the hands of men who despised the Sangha.”62

Initially, the charter was approved by the Sun Yat-sen’s government but it immediately provoked the anger of many other Buddhists, among them the most venerable monks of the age, such as Jichan (Chinese, 1852-1912) also known as the ”Eight Fingered Ascetic” [Chinese], Xuyun (Chinese?-1959) and Taixu. Their reaction was to found a new Buddhist Association in Shanghai headed by the charismatic Jichan, the abbot of Tiantong Temple. Most people in Buddhist circles accepted this association, and consequently Ouyang’s Association was dissolved by itself. According to Xu and Wang, Ouyang avoided discussing this unflattering incident, which brought him many enemies within the Buddhist world.63

Ouyang’s failure to establish himself as a public figure is not surprising, since he cut himself off from the more “popular religion” and tried to “correct flaws” in Chinese Buddhism that were dear to most of other Buddhists (e.g. ritual, meditative practices and mainstream doctrines). Ouyang was destined to leave his mark in another realm, that which he knew best, the realm of ideas and of intellectual engagement.

2.3.4 Studies in Yogacara, Financial Challenges and Growing Reputation

2.3.4.1 Yogacara (Weishi) Scholasticism

After the failure of Ouyang’s “Coup de Sangha,” he continued to devote most of his time and effort to the study of Yogacara Buddhism. As noted earlier, Ouyang had already been immersed in studies of Yogacara since his first meeting with Yang Wenhui in 1904. Eight years later, Ouyang had a much more comprehensive view of the Buddhist tradition, which encompassed a wide array of texts from different textual traditions. Ouyang did not learn Sanskrit but he was especially determined to explore the entire breadth of Indian Yogacara based on the Xuanzang corpus.64

The Xuanzang corpus had not been seriously examined since at least the Ming dynasty. The sixth and seventh centuries were the heyday of Yogacara studies in China. After the passing of Xuanzang in 664 CE, Yogacara declined for philosophical and political reasons, i.e. due to shifts in imperial patronage65 and an effective criticism of Xuanzang’s doctrinal positions.66 Many of the commentaries that elucidated the technical terminology of the Yogacara tradition were lost in the upheavals of the second half of the Tang Empire and the Yogacara teaching became “provisional” teaching.67

Yogacara study during the Ming-Qing period was scarce. Texts were only partially accessible and were considered only as a background reading to the more “perfect teachings.” When Yogacara was studied, it was done thorough textbooks such as the Eight Essential [Texts] of the Faxiang School68 [Chinese], written by Xuelang Hongen (Chinese,1545-1608), or The Essential teaching of the Mind Contemplation in the Cheng weishi lun69 (Chinese), by Ouyi Zhixu (Chinese 1599-1655). Ouyang Jingwu was very critical of the Yogacara studies that were conducted during the Ming and later. For him, while Ming Yogacarins did study important texts like the Trimsika or the Cheng weishi lun, they also left out many important texts, such as the entire Asanga corpus.70

Ouyang was more comprehensive, and studied the notable Yogacara treatises known collectively as the “One Root [text] and the 10 Branches” 71 (Chinese). The root text is the encyclopedic work traditionally attributed to Asanga, the Yogacarabhumi Sastra.72 The fact that that there was no living tradition of Yogacara studies in China and that Ouyang had to rely solely on his Chinese sources and philological training made his reading of this enormous corpus especially challenging.73

In 1915, Ouyang’s research into Yogacara deepened following a tragic event. When Ouyang Jingwu was appointed by Yang Wenhui to continue his work in the Jinling printery Ouyang Lan, his daughter, came to Nanjing from their hometown in Yihuang County. She studied there and took care of Ouyang Jingwu’s household. The relationship between Ouyang Jingwu and his daughter was close and he was very attached to her. In 1915, when Ouyang was in Gansu for fundraising purposes, Ouyang Lan fell ill, and died soon after. Ouyang learned of her death only upon his return from Gansu. In a letter to his disciple he recounted, “I wailed at night and felt utterly hopeless.”74 After her death his research of Yogacara became a therapeutic device and spiritual solace that helped him to mitigate the sadness over the loss of his daughter.

In 1917, Ouyang finished publishing the last fifty fascicles of the Yogacarabhumi as he had promised Yang Wenhui and also concluded an intensive five years of research focusing primarily on the Yogacarabhumi, which he prepared for publication. This period of focusing on Yogacara studies culminated in the publication of his influential preface to the Yogacarabhumi sastra (Chinese). Around the time of the Yogacarabhumi publication, Ouyang also published other important texts to which he added his commentaries. 75His commentaries were most often prefaces (Chinese), in which he outlined the different components of the treatise together with its philosophical content, and added his own analysis and gave the historical context of the sutra or sastra and its author. The analysis section was where he most often was more creative and innovative.

Ouyang’s commentaries were intellectually engaging and relevant for his contemporaries. He thus achieved in them both goals of keeping Yang Wenhui’s mission going, and of building his own status, which would enable him to carry on his academic and publication plans. Ouyang’s background in evidential scholarship and growing familiarity with Abhidharma and Yogacara texts brought Buddhist scholarship in China to a new level of thoroughness and precision. His depth of philosophical and philological analysis enabled him to clarify to his contemporaries the abstruse teaching and vocabulary of Buddhism philosophy, and convince leading intellectuals like Liang Qichao, Liang Shuming, and Xiong Shili of the importance of Buddhism. He also criticized the “flaws” he saw in Chinese Buddhism in a way that forced the more traditional forces in the Sangha to react with an equal level of sophistication. Some of the innovations and elucidations were so different from what Chinese Buddhists and intellectuals were used to that Lü Cheng tells us that his audience “was shocked.”76

2.3.4.2 Financial difficulties and growing reputation

Financial challenges had been a part of Ouyang’s life since early childhood and throughout his adulthood. Finances affected both his family’s situation, the Jinling printery, and later also, later, the Inner Studies Institute.

As noted above, before Yang Wenhui died he attempted to secure both the continuous operation of the Jinling printery and the well-being of his family. The solution that he found was awkward and gave rise to numerous misunderstandings. The Jinling printery was granted independence, but on the condition that the Yang family could live in two of the four main courtyards and that they, on their part, would support the Jinling printery when they are able to afford it.77 Conflicts between Ouyang and Yang family over the support of the family and real estate began right after Yang Wenhui’s death and lasted until 1936. 78

Dedicating all of his time and energy to the Jinling printery had an enormous impact on the well-being and economic situation of Ouyang’s own family. As we saw earlier, the most tragic instance was the death of his daughter while Ouyang was on a fundraising trip in 1915. Ouyang lamented his loss bitterly and the fact that he was not around when his daughter needed him the most must have caused him serious distress. Both as a child and later as an adult, Ouyang never lived a life of comfort, a price that he paid for dedicating himself to scholarship and education.

While economically Ouyang faced challenges and uncertainties, his fame and reputation as a scholar soared. His name was known already in 1912 after his failure in forming the Chinese Buddhist Association. Naturally, he was well known in Yang Wenhui’s circle, where he gradually became known as the Yogacara expert. In the years after Yang’s death, his reputation grew as an independent thinker and he was hailed by prominent intellectuals such as Zhang Taiyan and Shen Zengzhi79 for his unique contribution to the study of Buddhism.

In the following decade, Ouyang’s name was well established as a Buddhist authority. Young intellectuals came to study under him, and other prominent monks, like Taixu or Yinguang, criticized him and debated his views. His name appears in several national and international conferences and associations. For example, in 1920 the Yunnan military governor Tang Jiyao established a Dharma association and invited Ouyang to lecture on sutras. Tang invited the most important monks of his time, Yinguang, Taixu and Dixian, and none of them could (or would) come, but Ouyang agreed. Finding Ouyang on the same list as these respected monks suggests that his authority as a Buddhist teacher was already established by 1920. In addition, in 1924, Taixu tried to establish the World Buddhist Federation, and he enlisted Ouyang as one of the delegates.80 In 1925, Ouyang was invited for a conference on Buddhism in Japan.81 The quotes from the opening from James Bissett Pratt and Karl Ludvig Reichelt at the opening of my introduction above suggest that Ouyang’s name was well known enough that non-Chinese visitors to the ROC either knew about him or even visited the Inner Studies Institution and met him in person. Above all, the flock of adherents that came to his institute, together with the examples mentioned above, suggest that these were years when Ouyang emerged from anonymity to become an established authority on Buddhism, at least among intellectuals and members of the elite.