Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#2)

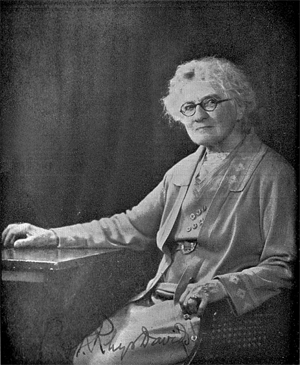

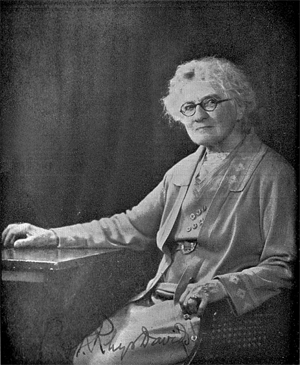

Caroline Rhys Davids

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/14/20

Caroline Augusta Foley Rhys Davids

Born: 27 September 1857, Wadhurst, England

Died: 26 June 1942, Chipstead, England

Nationality: British

Alma mater: University College London

Scientific career

Fields: Buddhist Studies

Institutions: School of Oriental and African Studies, Victoria University of Manchester (today University of Manchester)

Caroline Augusta Foley Rhys Davids (1857–1942) was a British writer and translator. She made a contribution to economics before becoming widely known as an editor, translator, and interpreter of Buddhist texts in the Pāli language. She was honorary secretary of the Pāli Text Society from 1907, and its president from 1923 to 1942.[1]

Early life and education

Caroline Augusta Foley was born on 27 September 1857 in Wadhurst, East Sussex, England to John Foley and Caroline Elizabeth Foley (née Windham). She was born into a family with a long ecclesiastic history: her father, John Foley, served as the vicar of Wadhurst from 1847–88; her grandfather and great grandfather had served as rector of Holt, Worcestershire and vicar of Mordiford, Herefordshire, respectively. Two years before her birth, five of her siblings died within one month in December 1855/January 1856 from diphtheria and are commemorated in the church of St Peter and St Paul, Wadhurst.[2][3] One surviving brother, John Windham Foley (1848–1926), became a missionary in India and another, Charles Windham Foley (1856–1933), played in three FA Cup Finals for Old Etonians, being on the winning side in 1852; he later had a career as a solicitor.[4]

Rhys Davids was home schooled by her father and then attended University College, London studying philosophy, psychology, and economics (PPE). She completed her BA in 1886 and an MA in philosophy in 1889. During her time at University College, she won both the John Stuart Mill Scholarship ...

and the Joseph Hume Scholarship. It was her psychology tutor George Croom Robertson who "sent her to Professor Rhys Davids",[5] her future husband, to further her interest in Indian philosophy. She also studied Sanskrit and Indian Philosophy with Reinhold Rost.

Thomas Rhys Davids was elected a fellow of University College in 1896. Caroline Rhys Davids was awarded an honorary D.Litt. degree by the Victoria University of Manchester (today University of Manchester) in 1919.[6]

Career

As a student, she was already a prolific writer and a vocal campaigner in the movements for poverty relief, children's rights, and women's suffrage.

Before moving into Buddhist studies, Rhys Davids made a contribution to Economics. She wrote seventeen entries for Palgrave Dictionary of Political Economy (1894-99/1910), including "Rent of ability," "Science, Economic, as distinguished from art," "Statics, Social, and social dynamics," as well as twelve biographical entries. Her entry, "Fashion, economic influence of," was related to her 1893 Economic Journal article, "Fashion," and reflects an unusual economic interest (see Fullbrook 1998). She also translated articles for the Economic journal from the German, French and Italian, including Carl Menger's influential 1892 article "On the Origin of Money".[7] In 1896 Rhys Davids published two sets of lecture notes by her former teacher and mentor George Croom Robertson: one on psychology[8] and one on philosophy.[9]

Rhys Davids was on the editorial board of the Economic Journal from 1891 to 1895.

T. W. Rhys Davids encouraged, his then pupil, Caroline to pursue Buddhist studies and do research about Buddhist psychology and the place of women in Buddhism. Thus, among her first works were a translation of the Dhamma Sangani, a text from the Theravāda Abhidhamma Piṭaka, which she published under the title A Buddhist manual of psychological ethics: Being a translation, now made for the first time, from the original Pāli, of the first book in the Abhidhamma Piṭaka, entitled: Dhamma-sangaṇi (Compendium of States or Phenomena) (1900); a second early translation was that of the Therīgāthā, a canonical work of verses traditionally ascribed to early Buddhist nuns (under the title Psalms of the Sisters [1909]).

Rhys Davids held two academic positions: Lecturer in Indian Philosophy at Victoria University of Manchester (today University of Manchester) (1910-1913); and Lecturer in the History of Buddhism at the School of Oriental Studies, later renamed the School of Oriental and African Studies (1918-1933). While teaching, she simultaneously acted as the Honorary Secretary of the Pāli Text Society which had been started by T. W. Rhys Davids to transcribe and translate Pāli Buddhist texts in 1881. She held that position from 1907 until her husband's death in 1922; the following year, she took his place as President of the Society.[10]

Her translations of Pāli texts were at times idiosyncratic, but her contribution as editor, translator, and interpreter of Buddhist texts was considerable. She was one of the first scholars to translate Abhidhamma texts, known for their complexity and difficult use of technical language. She also translated large portions of the Sutta Piṭaka, or edited and supervised the translations of other PTS scholars. Beyond this, she also wrote numerous articles and popular books on Buddhism; it is in these manuals and journal articles where her controversial volte-face towards several key points of Theravāda doctrine can first be seen.

After the death of her son in 1917 and her husband in 1922, Rhys Davids turned to Spiritualism. She became particularly involved in various forms of psychic communication with the dead, first attempting to reach her dead son through seances and then through automatic writing. She later claimed to have developed clairaudience, as well as the ability to pass into the next world when dreaming. She kept extensive notebooks of automatic writing, along with notes on the afterlife and diaries detailing her experiences. These notes form part of her archive jointly held by the University of Cambridge[11] and the University of London.[12]

Although earlier in her career she accepted more mainstream beliefs about Buddhist teachings, later in life she rejected the concept of anatta as an "original" Buddhist teaching. She appears to have influenced several of her students in this direction, including A. K. Coomaraswamy, F. L. Woodward, and I. B. Horner.

Family

The fighter ace Arthur Rhys Davids. He died in action on 23 October 1917, aged just twenty.

Caroline Augusta Foley married Thomas William Rhys Davids in 1894. They had three children: Vivien Brynhild Caroline Foley Rhys Davids (1895-1978), Arthur Rhys Davids (1897-1917), and Nesta Enid (1900-1973).

Vivien won the Clara Evelyn Mordan Scholarship to St Hugh's College, Oxford in 1915,[13] later serving as a Surrey County Councillor, and receiving an MBE in 1973.[14] Arthur was a gifted scholar and a decorated World War I fighter ace, but was killed in action in 1917. Neither Vivien nor Nesta married or had children.

Rhys Davids died suddenly in Chipstead, Surrey on 26 June 1942. She was 84.

Works and translations

Books

• Buddhism: A Study of the Buddhist Norm (1912)

• Buddhist Psychology: An Inquiry into the Analysis and Theory of Mind in Pāli Literature (1914)

• Old Creeds and New Needs (1923)

• The Will to Peace (1923)

• Will & Willer (1926)

• Gotama the Man (1928)

• Sakya: or, Buddhist Origins (1928)

• Stories of the Buddha : Being Selections from the Jataka (1929)

• Kindred Sayings on Buddhism (1930)

• The Milinda-questions : An Inquiry into its Place in the History of Buddhism with a Theory as to its Author (1930)

• A Manual of Buddhism for Advanced Students (1932)

• Outlines of Buddhism: A Historical Sketch (1934)

• Buddhism: Its Birth and Dispersal (1934) - A completely rewritten work to replace Buddhism: A Study of the Buddhist Norm (1912)

• Indian Religion and Survival: A Study (1934)

• The Birth of Indian Psychology and its Development in Buddhism (1936)

• To Become or not to Become (That is the Question!): Episodes in the History of an Indian Word (1937)

• What is your Will (1937) - A rewrite of Will & Willer

• What was the original gospel in 'Buddhism'? (1938)

• More about the Hereafter (1939)

• Wayfarer's Words, V. I-III - A compilation of most of C. A. F. Rhys Davids articles and lectures, mostly from the latter part of her career. V. I (1940), V. II (1941), V. III (1942 - posthumously)

Translations

• A Buddhist manual of psychological ethics or Buddhist Psychology, of the Fourth Century B.C., being a translation, now made for the first time, from the Original Pāli of the First Book in the Abhidhamma-Piţaka, entitled Dhamma-Sangaṇi (Compendium of States or Phenomena) (1900). (Includes an original 80-page introduction.) Reprint currently available from Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-4702-9.

• Psalms of the Early Buddhists: Volume I. Psalms of the Sisters. By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. London: Pāli Text Society, 1909, at A Celebration of Women Writers

• Points of controversy; or, Subjects of discourse; being a translation of the Kathā-vatthu from the Abhidhamma-piṭaka, Co-authored with Shwe Zan Aung (1915)

Articles

• On the Will in Buddhism By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (1898) pp. 47–59

• Notes on Early Economic Conditions in Northern India By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (1901) pp. 859–888

• The Soul-Theory in Buddhism By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1903) pp. 587–591

• Buddhism and Ethics By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Buddhist Review Vol. 1 No. 1. (1909) pp. 13–23

• Intellect and the Khandha Doctrine By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Buddhist Review. Vol. 2. No. 1 (1910) pp. 99–115

• Pāli Text Society By Shwe Zan Aung and C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. (1917) pp. 403–406

• The Patna Congress and the "Man" By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (1929) pp. 27–36

• Original Buddhism and Amṛta By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. Melanges chinois et bouddhiques. July 1939. pp. 371–382

See also

• Buddhism and psychology

• Indian psychology

Notes

1. 'DAVIDS, Caroline A. F. Rhys', Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014. accessed 28 Sept 2017[permanent dead link]

2. "Church Guide" (PDF). Wadhurst Parish Church. p. 13. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

3. Payne, Russell (21 May 2012). "The Foley Family. A tragedy from the past (The Secrets of Wadhurst Church)". YouTube. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

4. Warsop, Keith (2004). The Early F.A. Cup Finals and the Southern Amateurs. Soccer Data. p. 79. ISBN 1-899468-78-1.

5. Revell, Alex. (1984). Brief Glory: The Life of Arthur Rhys Davids. William Kimber, p.14.

6. University of Manchester, Register of Graduates And Holders of Diplomas And Certificates 1851–1958 [filed under Davids]

7. Robert W. Dimand. (1999) Women Economists in the 1890s: Journals, Books and the Old Palgrave. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 21 (3): 272

8. Robertson, George, Croom. (1896a). Elements of Psychology. Ed. by Davids, C. A. F. Rhys. 1896. https://archive.org/stream/elementsofps ... i/mode/2up

9. Robertson, George, Croom. (1896b) Elements of General Philosophy. Ed. by Davids, C. A. F. Rhys. https://archive.org/details/elementsofconstr00robeuoft

10. 'DAVIDS, Caroline A. F. Rhys', Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014. accessed 28 Sept 2017[permanent dead link]

11. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

12. https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/a ... 1f66355c86

13. https://issuu.com/sthughscollegeoxford/ ... 34-1935/41

14. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

References

• 'DAVIDS, Caroline A. F. Rhys', in Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014. (online edn, April 2014) accessed 28 Sept 2017[permanent dead link]

• Neal, Dawn. (2014) The Life and Contributions of CAF Rhys Davids. The Sati Journal, 2: 15–31. https://www.academia.edu/11805005/The_L ... hys_Davids

• Robert W. Dimand. (1999) Women Economists in the 1890s: Journals, Books and the Old Palgrave. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 21 (3): 269

• Snodgrass, Judith (2007). "Defining Modern Buddhism: Mr. and Mrs. Rhys Davids and the Pāli Text Society." Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 27:1, 186–202. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cst/summar ... grass.html.

• Wickremeratne, Ananda. The Genesis of an Orientalist: Thomas William Rhys Davids and Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1984. ISBN 0-8364-0867-5.

• Stede, W. (1942). "Caroline Augusta Foley Rhys Davids: (27th September, 1857 – 26th June, 1942)", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 3, 267-268

External links

• Mrs. Rhys Davids' Dialogue with Psychology (1893-1924) By Teresina Rowell Havens. Philosophy East & West. V. 14 (1964) pp. 51–58

• Records of Caroline Rhys Davids at Senate House Library, University of London

• "LC Online Catalog - Caroline Rhys Davids". catalog.loc.gov. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

• University of Cambridge Library Archive Collection - Rhys Davids Family

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/14/20

Caroline Augusta Foley Rhys Davids

Born: 27 September 1857, Wadhurst, England

Died: 26 June 1942, Chipstead, England

Nationality: British

Alma mater: University College London

Scientific career

Fields: Buddhist Studies

Institutions: School of Oriental and African Studies, Victoria University of Manchester (today University of Manchester)

Caroline Augusta Foley Rhys Davids (1857–1942) was a British writer and translator. She made a contribution to economics before becoming widely known as an editor, translator, and interpreter of Buddhist texts in the Pāli language. She was honorary secretary of the Pāli Text Society from 1907, and its president from 1923 to 1942.[1]

Early life and education

Caroline Augusta Foley was born on 27 September 1857 in Wadhurst, East Sussex, England to John Foley and Caroline Elizabeth Foley (née Windham). She was born into a family with a long ecclesiastic history: her father, John Foley, served as the vicar of Wadhurst from 1847–88; her grandfather and great grandfather had served as rector of Holt, Worcestershire and vicar of Mordiford, Herefordshire, respectively. Two years before her birth, five of her siblings died within one month in December 1855/January 1856 from diphtheria and are commemorated in the church of St Peter and St Paul, Wadhurst.[2][3] One surviving brother, John Windham Foley (1848–1926), became a missionary in India and another, Charles Windham Foley (1856–1933), played in three FA Cup Finals for Old Etonians, being on the winning side in 1852; he later had a career as a solicitor.[4]

Rhys Davids was home schooled by her father and then attended University College, London studying philosophy, psychology, and economics (PPE). She completed her BA in 1886 and an MA in philosophy in 1889. During her time at University College, she won both the John Stuart Mill Scholarship ...

In 1841 [John William Kaye] resigned from the army and began to write for newspapers such as the Bengal Harkaru. In 1844 he started the Calcutta Review while also writing a novel based in Afghanistan. In 1856 he entered the civil service of the East India Company, and when in 1858 the government of India was transferred to the British crown, he succeeded John Stuart Mill as secretary of the political and secret department of the India office.

-- John William Kaye, by Wikipedia

and the Joseph Hume Scholarship. It was her psychology tutor George Croom Robertson who "sent her to Professor Rhys Davids",[5] her future husband, to further her interest in Indian philosophy. She also studied Sanskrit and Indian Philosophy with Reinhold Rost.

Reinhold Rost (1822–1896) was a German orientalist, who worked for most of his life at St Augustine's Missionary College, Canterbury in EnglandSt Augustine’s College in Canterbury, Kent, United Kingdom, was located within the precincts of St Augustine's Abbey about 0.2 miles (335 metres) ESE of Canterbury Cathedral. It served first as a missionary college of the Church of England (1848-1947) and later as the Central College of the Anglican Communion (1952-1967).

The mid-19th century witnessed a "mass-migration" from England to its colonies. In response, the Church of England sent clergy, but the demand for them to serve overseas exceeded supply. Colonial bishoprics were established, but the bishops were without clergy. The training of missionary clergy for the colonies was “notoriously difficult” because they were required to have not only “piety and desire”, they were required to have an education “equivalent to that of a university degree”. The founding of the missionary college of St Augustine’s provided a solution to this problem.

The Revd Edward Coleridge, a teacher at Eton College, envisioned establishing a college for the purpose of training clergy for service in the colonies: both as ministers for the colonists and as missionaries to the native populations...

-- St Augustine's College, Canterbury, by Wikipedia

and as head librarian at the India Office Library, London.

He was the son of Christian Friedrich Rost, a Lutheran minister, and his wife Eleonore Glasewald, born at Eisenberg in Saxen-Altenburg on 2 February 1822. He was educated at the Eisenberg gymnasium school, and, after studying under Johann Gustav Stickel and Johann Gildemeister, graduated Ph.D. at the University of Jena in 1847. In the same year he came to England, to act as a teacher in German at the King's School, Canterbury. After four years, on 7 February 1851, he was appointed oriental lecturer at St. Augustine's Missionary College, Canterbury, founded to educate young men for mission work. This post he held for the rest of his life.

In London, Rost met Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, and was elected, in December 1863, secretary to the Royal Asiatic Society, a post he held for six years.Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, GCB FRS (5 April 1810 – 5 March 1895) was a British East India Company army officer, politician and Orientalist, sometimes described as the Father of Assyriology. His son, also Henry, was to become a senior commander in the British Army during World War I...

Rawlinson was appointed political agent at Kandahar in 1840. In that capacity he served for three years, his political labours being considered as meritorious as was his gallantry during various engagements in the course of the Afghan War; for these he was rewarded by the distinction of Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1844.

Serendipitously, he became known personally to the governor-general, which resulted in his appointment as political agent in Ottoman Arabia. Thus he settled in Baghdad, where he devoted himself to cuneiform studies. He was now able, with considerable difficulty and at no small personal risk, to make a complete transcript of the Behistun inscription, which he was also successful in deciphering and interpreting. Having collected a large amount of invaluable information on this and kindred topics, in addition to much geographical knowledge gained in the prosecution of various explorations (including visits with Sir Austen Henry Layard to the ruins of Nineveh), he returned to England on leave of absence in 1849.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in February 1850 on account of being "The Discoverer of the key to the Ancient Persian, Babylonian, and Assyrian Inscriptions in the Cuneiform character. The Author of various papers on the philology, antiquities, and Geography of Mesopotamia and Central Asia. Eminent as a Scholar".

Rawlinson remained at home for two years, published in 1851 his memoir on the Behistun inscription, and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He disposed of his valuable collection of Babylonian, Sabaean, and Sassanian antiquities to the trustees of the British Museum, who also made him a considerable grant to enable him to carry on the Assyrian and Babylonian excavations initiated by Layard. During 1851 he returned to Baghdad. The excavations were performed by his direction with valuable results, among the most important being the discovery of material that contributed greatly to the final decipherment and interpretation of the cuneiform character. Rawlinson's greatest contribution to the deciphering of the cuneiform scripts was the discovery that individual signs had multiple readings depending on their context. While at the British Museum, Rawlinson worked with the younger George Smith.

An equestrian accident in 1855 hastened his determination to return to England, and in that year he resigned his post in the East India Company. On his return to England the distinction of Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath was conferred upon him, and he was appointed a crown director of the East India Company.

The remaining forty years of his life were full of activity—political, diplomatic, and scientific—and were spent mainly in London. In 1858 he was appointed a member of the first India Council, but resigned during 1859 on being sent to Persia as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary. The latter post he held for only a year, owing to his dissatisfaction with circumstances concerning his official position there. Previously he had sat in Parliament as Member of Parliament (MP) for Reigate from February to September 1858; he was again MP for Frome, from 1865 to 1868. He was appointed to the Council of India again in 1868, and continued to serve upon it until his death. He was a strong advocate of the forward policy in Afghanistan, and counselled the retention of Kandahar.

Rawlinson was one of the most important figures arguing that Britain must check Russian ambitions in South Asia. He was a strong advocate of the forward policy in Afghanistan, and counselled the retention of Kandahar. He argued that Tsarist Russia would attack and absorb Khokand, Bokhara and Khiva (which they did – they are now parts of Uzbekistan) and warned they would invade Persia (present-day Iran) and Afghanistan as springboards to British India.

He was a trustee of the British Museum from 1876 till his death. He was created Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1889, and a Baronet in 1891; was president of the Royal Geographical Society from 1874 to 1875, and of the Royal Asiatic Society from 1869 to 1871 and 1878 to 1881; and received honorary degrees at Oxford, Cambridge, and Edinburgh.

-- Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, by Wikipedia

Through Rawlinson he became on 1 July 1869 librarian at the India Office, on the retirement of FitzEdward Hall, and imposed order on its manuscripts.Fitzedward Hall (March 21, 1825 - February 1, 1901) was an American Orientalist, and philologist. He was the first American to edit a Sanskrit text, and was an early collaborator in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) project...

He graduated with the degree of civil engineer from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute at Troy in 1842, and entered Harvard in the class of 1846. His Harvard classmates included Charles Eliot Norton, who later visited him in India in 1849, and Francis James Child. Just before his class graduated but after completing the work for his degree he abruptly left college and took ship out of Boston to India, allegedly in search of a runaway brother. His ship foundered and was wrecked on its approach to the harbor of Calcutta, where he found himself stranded. Although it was not his intention, he was never to return to the United States. At this time, he began his study of Indian languages, and in January 1850 he was appointed tutor in the Government Sanskrit College at Benares. In 1852, he became the first American to edit a Sanskrit text, namely the Vedanta treatises Ātmabodha and Tattvabodha. In 1853, he became professor of Sanskrit and English at the Government Sanskrit College; and in 1855 was appointed to the post of Inspector of Public Instruction in Ajmere-Merwara and in 1856 in the Central Provinces.

In 1857, Hall was caught up in the Sepoy Mutiny. The Manchester Guardian later gave this account:[2] "When the Mutiny broke out he was Inspector of Public Instruction for Central India, and was beleaguered in the Saugor Fort. He had become an expert tiger shooter, and turned this proficiency to account during the siege of the fort, and afterwards as a volunteer in the struggle for the re-establishment of the British power in India."

In 1859, he published at Calcutta his discursive and informative A Contribution Towards an Index to the Bibliography of the Indian Philosophical Systems, based on the holdings of the Benares College and his own collection of Sanskrit manuscripts, as well as numerous other private collections he had examined. In the introduction, he regrets that this production was in press in Allahabad and would have been put before the public in 1857, "had it not been impressed to feed a rebel bonfire."

He settled in England and in 1862 received the appointment to the Chair of Sanskrit, Hindustani and Indian jurisprudence in King's College London, and to the librarianship of the India Office. An unsuccessful attempt was made by his friends to lure him back to Harvard by endowing a Chair of Sanskrit for him there, but this project came to nothing. His collection of a thousand Oriental manuscripts he gave to Harvard...

In 1869 Hall was dismissed by the India Office, which accused him (by his own account) of being a drunk and a foreign spy, and expelled from the Philological Society after a series of acrimonious exchanges in the letters columns of various journals.

-- Fitzedward Hall, by Wikipedia

He secured for students free admission to the library. He retired in 1893 after 24 years of service at the age of 70. His successor as head librarian of the India Office Library became the Orientalist and Sanskritist Charles Henry Tawney (1837-1922).

Rost gained many distinctions and awards. He was created Hon. LL.D. of Edinburgh in 1877, and a Companion of the Indian Empire in 1888. He died at Canterbury on 7 February 1896.[1]

-- Reinhold Rost, by Wikiedia

Thomas Rhys Davids was elected a fellow of University College in 1896. Caroline Rhys Davids was awarded an honorary D.Litt. degree by the Victoria University of Manchester (today University of Manchester) in 1919.[6]

Career

As a student, she was already a prolific writer and a vocal campaigner in the movements for poverty relief, children's rights, and women's suffrage.

Before moving into Buddhist studies, Rhys Davids made a contribution to Economics. She wrote seventeen entries for Palgrave Dictionary of Political Economy (1894-99/1910), including "Rent of ability," "Science, Economic, as distinguished from art," "Statics, Social, and social dynamics," as well as twelve biographical entries. Her entry, "Fashion, economic influence of," was related to her 1893 Economic Journal article, "Fashion," and reflects an unusual economic interest (see Fullbrook 1998). She also translated articles for the Economic journal from the German, French and Italian, including Carl Menger's influential 1892 article "On the Origin of Money".[7] In 1896 Rhys Davids published two sets of lecture notes by her former teacher and mentor George Croom Robertson: one on psychology[8] and one on philosophy.[9]

George Croom Robertson (10 March 1842 – 20 September 1892) was a Scottish philosopher. He sat on the Committee of the National Society for Women's Suffrage and his wife, Caroline Anna Croom Robertson was a college administrator.

He was born in Aberdeen. In 1857 he gained a bursary at Marischal College, and graduated MA in 1861, with the highest honours in classics and philosophy. In the same year he won a Fergusson scholarship of £100 a year for two years, which enabled him to pursue his studies outside Scotland. He went first to University College, London; at the University of Heidelberg he worked on his German; at the Humboldt University in Berlin he studied psychology, metaphysics and also physiology under Emil du Bois-Reymond,...Emil Heinrich du Bois-Reymond (7 November 1818 – 26 December 1896) was a German physician and physiologist, the co-discoverer of nerve action potential, and the developer of experimental electrophysiology.

Du Bois-Reymond was born in Berlin and spent his working life there. One of his younger brothers was the mathematician Paul du Bois-Reymond (1831–1889). His father was from Neuchâtel, and his mother was a Berliner of Huguenot origin.[1][2]

Educated first at the French College in Berlin, du Bois-Reymond enrolled in the University of Berlin in 1838. He seems to have been uncertain at first as to the topic of his studies, for he was a student of the renowned ecclesiastical historian August Neander, and dallied with geology and physics, but eventually began to study medicine with such zeal and success as to attract the notice of Johannes Peter Müller (1801–1858), a well-known professor of anatomy and physiology...

During 1840 Müller made du Bois-Reymond his assistant in physiology, and as the beginning of an inquiry gave him a copy of the essay which the Italian Carlo Matteucci had just published on the electric phenomena of animals. This determined the work of du Bois-Reymond's life. He chose as the subject of his graduation thesis Electric fishes, and so commenced a long series of investigations on bioelectricity. The results of these inquiries were made known partly in papers communicated to scientific journals, but also and chiefly by his work Investigations of Animal Electricity, the first part of which was published in 1848, the last in 1884.

-- Emil du Bois-Reymond, by Wikipedia

and heard lectures on Hegel, Kant and the history of philosophy, ancient and modern. After two months at the University of Göttingen, he went to Paris in June 1863. In the same year he returned to Aberdeen and helped Alexander Bain with the revision of some of his books.

In 1864 he was appointed to help William Duguid Geddes with his Greek classes, but he devoted his vacations to working on philosophy. In 1866 he was appointed professor of philosophy of mind and logic at University College, London. He remained there until he was forced by ill-health to resign a few months before his death, lecturing on logic, deductive and inductive, systematic psychology and ethics...

Together with Bain, he edited George Grote's Aristotle, and was the editor of Mind from its foundation in 1876 till 1891.The society's annual conference, organised since 1918 in conjunction with the Mind Association, (publishers of the philosophical journal Mind), is known as the Joint Session of the Aristotelian Society and the Mind Association, and is hosted by different university departments in July each year.The Mind Association is a philosophical society whose purpose is to promote the study of philosophy. The association publishes the journal Mind quarterly.

Mind is a quarterly peer-reviewed academic journal published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Mind Association....

Early on, the journal was dedicated to the question of whether psychology could be a legitimate natural science. In the first issue, Robertson wrote:

Now, if there were a journal that set itself to record all advances in psychology, and gave encouragement to special researches by its readiness to publish them, the uncertainty hanging over the subject could hardly fail to be dispelled. Either psychology would in time pass with general consent into the company of the sciences, or the hollowness of its pretensions would be plainly revealed. Nothing less, in fact, is aimed at in the publication of Mind than to procure a decision of this question as to the scientific standing of psychology.

-- Mind (journal), by Wikipedia

It was established in 1900 on the death of Henry Sidgwick [one of the founders and first president of the Society for Psychical Research; a member of the Metaphysical Society, and the Cambridge Apostles, a lifelong homosexual, married to Eleanor Mildred Balfour, sister to Arthur Balfour], who had supported Mind financially since 1891 and had suggested that after his death the society should be formed to oversee the journal.

-- Mind Association, by Wikipedia

The first edition of the society's proceedings, the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society for the Systematic Study of Philosophy, now the Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, was issued in 1888.

-- Aristotelian Society, by Wikipedia

Robertson had a keen interest in German philosophy, and took every opportunity to make German works on English writers known in the United Kingdom. In philosophy he was a follower of Bain...Alexander Bain (11 June 1818 – 18 September 1903) was a Scottish philosopher and educationalist in the British school of empiricism and a prominent and innovative figure in the fields of psychology, linguistics, logic, moral philosophy and education reform. He founded Mind, the first ever journal of psychology and analytical philosophy, and was the leading figure in establishing and applying the scientific method to psychology. Bain was the inaugural Regius Chair in Logic and Professor of Logic at the University of Aberdeen, where he also held Professorships in Moral Philosophy and English Literature and was twice elected Lord Rector of the University of Aberdeen...

In 1836 he entered Marischal College where he came under the influence of Professor of Mathematics John Cruickshank, Professor of Chemistry Thomas Clark and Professor of Natural Philosophy William Knight. Towards the end of his undergraduate degree he became a contributor to the Westminster Review with his first article entitled "Electrotype and Daguerreotype," published in September 1840. This was the beginning of his connection with John Stuart Mill, which led to a lifelong friendship. He was awarded the Blue Ribbon and also the Gray Mathematical Bursary. His college career and studies was distinguished especially in mental philosophy, mathematics and physics and he graduated with a Master of Arts with Highest Honours.

In 1841, Bain substituted for Dr. Glennie the Professor of Moral Philosophy, who, due to ill-health, was unable to discharge his academic duties. He continued to do this three successive terms, during which he continued writing for the Westminster, and also helped John Stuart Mill with the revision of the manuscript of his System of Logic (1842). In 1843 he contributed the first review of the book to the London and Westminster...

Although his influence as a logician and linguist in grammar and rhetoric was considerable, his reputation rests on his works in psychology. At one with the German physiologist and comparative anatomist Johannes Peter Müller in the conviction psychologus nemo nisi physiologus (one is not a psychologist who is not also a physiologist), he was the first in Great Britain during the 19th century to apply physiology in a thoroughgoing fashion to the elucidation of mental states. In discussing the will, he favoured physiological over metaphysical explanations, pointing to reflexes as evidence that a form of will, independent of consciousness, inheres in a person's limbs. He sought to chart physiological correlates of mental states but refused to make any materialistic assumptions. He was the originator of the theory of psychophysical parallelism which is used widely as a working basis by modern psychologists. His idea of applying the scientific method of classification to psychical phenomena gave scientific character to his work, the value of which was enhanced by his methodical exposition and his command of illustration. In line with this, too, is his demand that psychology should be cleared of metaphysics; and to his lead is no doubt due in great measure the position that psychology has now acquired as a distinct positive science. Bain established psychology, as influenced by David Hume and Auguste Comte, as a more distinct discipline of science through application of the scientific method. Bain proposed that physiological and psychological processes were linked, and that traditional psychology could be explained in terms of this association. Moreover, he proposed that all knowledge and all mental processes had to be based on actual physical sensations, and not on spontaneous thoughts and ideas, and attempted to identify the link between the mind and the body and to discover the correlations between mental and behavioural phenomena.

William James calls his work the "last word" of the earlier stage of psychology.

-- Alexander Bain, by Wikipedia

and John Stuart Mill. He and his wife, the college administrator Caroline Anna Croom Robertson, were involved in social work; he sat on the Committee of the National Society for Women's Suffrage, and was actively associated with its president, John Stuart Mill. He also supported the admission of women students to University College.

-- George Croom Robertson, by Wikipedia

Rhys Davids was on the editorial board of the Economic Journal from 1891 to 1895.

T. W. Rhys Davids encouraged, his then pupil, Caroline to pursue Buddhist studies and do research about Buddhist psychology and the place of women in Buddhism. Thus, among her first works were a translation of the Dhamma Sangani, a text from the Theravāda Abhidhamma Piṭaka, which she published under the title A Buddhist manual of psychological ethics: Being a translation, now made for the first time, from the original Pāli, of the first book in the Abhidhamma Piṭaka, entitled: Dhamma-sangaṇi (Compendium of States or Phenomena) (1900); a second early translation was that of the Therīgāthā, a canonical work of verses traditionally ascribed to early Buddhist nuns (under the title Psalms of the Sisters [1909]).

Rhys Davids held two academic positions: Lecturer in Indian Philosophy at Victoria University of Manchester (today University of Manchester) (1910-1913); and Lecturer in the History of Buddhism at the School of Oriental Studies, later renamed the School of Oriental and African Studies (1918-1933). While teaching, she simultaneously acted as the Honorary Secretary of the Pāli Text Society which had been started by T. W. Rhys Davids to transcribe and translate Pāli Buddhist texts in 1881. She held that position from 1907 until her husband's death in 1922; the following year, she took his place as President of the Society.[10]

Her translations of Pāli texts were at times idiosyncratic, but her contribution as editor, translator, and interpreter of Buddhist texts was considerable. She was one of the first scholars to translate Abhidhamma texts, known for their complexity and difficult use of technical language. She also translated large portions of the Sutta Piṭaka, or edited and supervised the translations of other PTS scholars. Beyond this, she also wrote numerous articles and popular books on Buddhism; it is in these manuals and journal articles where her controversial volte-face towards several key points of Theravāda doctrine can first be seen.

After the death of her son in 1917 and her husband in 1922, Rhys Davids turned to Spiritualism. She became particularly involved in various forms of psychic communication with the dead, first attempting to reach her dead son through seances and then through automatic writing. She later claimed to have developed clairaudience, as well as the ability to pass into the next world when dreaming. She kept extensive notebooks of automatic writing, along with notes on the afterlife and diaries detailing her experiences. These notes form part of her archive jointly held by the University of Cambridge[11] and the University of London.[12]

Although earlier in her career she accepted more mainstream beliefs about Buddhist teachings, later in life she rejected the concept of anatta as an "original" Buddhist teaching. She appears to have influenced several of her students in this direction, including A. K. Coomaraswamy, F. L. Woodward, and I. B. Horner.

Family

The fighter ace Arthur Rhys Davids. He died in action on 23 October 1917, aged just twenty.

Caroline Augusta Foley married Thomas William Rhys Davids in 1894. They had three children: Vivien Brynhild Caroline Foley Rhys Davids (1895-1978), Arthur Rhys Davids (1897-1917), and Nesta Enid (1900-1973).

Vivien won the Clara Evelyn Mordan Scholarship to St Hugh's College, Oxford in 1915,[13] later serving as a Surrey County Councillor, and receiving an MBE in 1973.[14] Arthur was a gifted scholar and a decorated World War I fighter ace, but was killed in action in 1917. Neither Vivien nor Nesta married or had children.

Rhys Davids died suddenly in Chipstead, Surrey on 26 June 1942. She was 84.

Works and translations

Books

• Buddhism: A Study of the Buddhist Norm (1912)

• Buddhist Psychology: An Inquiry into the Analysis and Theory of Mind in Pāli Literature (1914)

• Old Creeds and New Needs (1923)

• The Will to Peace (1923)

• Will & Willer (1926)

• Gotama the Man (1928)

• Sakya: or, Buddhist Origins (1928)

• Stories of the Buddha : Being Selections from the Jataka (1929)

• Kindred Sayings on Buddhism (1930)

• The Milinda-questions : An Inquiry into its Place in the History of Buddhism with a Theory as to its Author (1930)

• A Manual of Buddhism for Advanced Students (1932)

• Outlines of Buddhism: A Historical Sketch (1934)

• Buddhism: Its Birth and Dispersal (1934) - A completely rewritten work to replace Buddhism: A Study of the Buddhist Norm (1912)

• Indian Religion and Survival: A Study (1934)

• The Birth of Indian Psychology and its Development in Buddhism (1936)

• To Become or not to Become (That is the Question!): Episodes in the History of an Indian Word (1937)

• What is your Will (1937) - A rewrite of Will & Willer

• What was the original gospel in 'Buddhism'? (1938)

• More about the Hereafter (1939)

• Wayfarer's Words, V. I-III - A compilation of most of C. A. F. Rhys Davids articles and lectures, mostly from the latter part of her career. V. I (1940), V. II (1941), V. III (1942 - posthumously)

Translations

• A Buddhist manual of psychological ethics or Buddhist Psychology, of the Fourth Century B.C., being a translation, now made for the first time, from the Original Pāli of the First Book in the Abhidhamma-Piţaka, entitled Dhamma-Sangaṇi (Compendium of States or Phenomena) (1900). (Includes an original 80-page introduction.) Reprint currently available from Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-4702-9.

• Psalms of the Early Buddhists: Volume I. Psalms of the Sisters. By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. London: Pāli Text Society, 1909, at A Celebration of Women Writers

• Points of controversy; or, Subjects of discourse; being a translation of the Kathā-vatthu from the Abhidhamma-piṭaka, Co-authored with Shwe Zan Aung (1915)

Articles

• On the Will in Buddhism By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (1898) pp. 47–59

• Notes on Early Economic Conditions in Northern India By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (1901) pp. 859–888

• The Soul-Theory in Buddhism By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1903) pp. 587–591

• Buddhism and Ethics By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Buddhist Review Vol. 1 No. 1. (1909) pp. 13–23

• Intellect and the Khandha Doctrine By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Buddhist Review. Vol. 2. No. 1 (1910) pp. 99–115

• Pāli Text Society By Shwe Zan Aung and C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. (1917) pp. 403–406

• The Patna Congress and the "Man" By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. (1929) pp. 27–36

• Original Buddhism and Amṛta By C. A. F. Rhys Davids. Melanges chinois et bouddhiques. July 1939. pp. 371–382

See also

• Buddhism and psychology

• Indian psychology

Notes

1. 'DAVIDS, Caroline A. F. Rhys', Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014. accessed 28 Sept 2017[permanent dead link]

2. "Church Guide" (PDF). Wadhurst Parish Church. p. 13. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

3. Payne, Russell (21 May 2012). "The Foley Family. A tragedy from the past (The Secrets of Wadhurst Church)". YouTube. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

4. Warsop, Keith (2004). The Early F.A. Cup Finals and the Southern Amateurs. Soccer Data. p. 79. ISBN 1-899468-78-1.

5. Revell, Alex. (1984). Brief Glory: The Life of Arthur Rhys Davids. William Kimber, p.14.

6. University of Manchester, Register of Graduates And Holders of Diplomas And Certificates 1851–1958 [filed under Davids]

7. Robert W. Dimand. (1999) Women Economists in the 1890s: Journals, Books and the Old Palgrave. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 21 (3): 272

8. Robertson, George, Croom. (1896a). Elements of Psychology. Ed. by Davids, C. A. F. Rhys. 1896. https://archive.org/stream/elementsofps ... i/mode/2up

9. Robertson, George, Croom. (1896b) Elements of General Philosophy. Ed. by Davids, C. A. F. Rhys. https://archive.org/details/elementsofconstr00robeuoft

10. 'DAVIDS, Caroline A. F. Rhys', Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014. accessed 28 Sept 2017[permanent dead link]

11. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 October 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

12. https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/a ... 1f66355c86

13. https://issuu.com/sthughscollegeoxford/ ... 34-1935/41

14. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

References

• 'DAVIDS, Caroline A. F. Rhys', in Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 2014. (online edn, April 2014) accessed 28 Sept 2017[permanent dead link]

• Neal, Dawn. (2014) The Life and Contributions of CAF Rhys Davids. The Sati Journal, 2: 15–31. https://www.academia.edu/11805005/The_L ... hys_Davids

• Robert W. Dimand. (1999) Women Economists in the 1890s: Journals, Books and the Old Palgrave. Journal of the History of Economic Thought, 21 (3): 269

• Snodgrass, Judith (2007). "Defining Modern Buddhism: Mr. and Mrs. Rhys Davids and the Pāli Text Society." Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 27:1, 186–202. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/cst/summar ... grass.html.

• Wickremeratne, Ananda. The Genesis of an Orientalist: Thomas William Rhys Davids and Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1984. ISBN 0-8364-0867-5.

• Stede, W. (1942). "Caroline Augusta Foley Rhys Davids: (27th September, 1857 – 26th June, 1942)", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 3, 267-268

External links

• Mrs. Rhys Davids' Dialogue with Psychology (1893-1924) By Teresina Rowell Havens. Philosophy East & West. V. 14 (1964) pp. 51–58

• Records of Caroline Rhys Davids at Senate House Library, University of London

• "LC Online Catalog - Caroline Rhys Davids". catalog.loc.gov. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

• University of Cambridge Library Archive Collection - Rhys Davids Family