Progressive Era

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/3/20

The Progressive movement was comprised of white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPs) who often sought to reform minorities and people from other religious and cultural backgrounds, leaving the shift of power in the hands of the WASPs...

Racism often pervaded most Progressive reform efforts, as evidenced by the suffrage movement. Specifically, as women campaigned for the vote, most Progressives argued on behalf of female suffrage as a necessary reform to combat the influence of “corrupted” or “ignorant” black voters in the election booth. Civil rights and Progressive reforms were thus mostly exclusionary projects that had little real influence on each other in the early twentieth century...

Progressivism for Whites Only

African Americans, immigrants from Asia, and Native Americans were largely excluded from the focus of Progressive reform...

Key Points

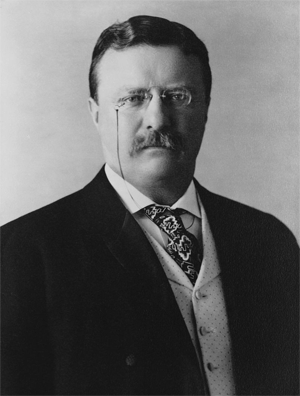

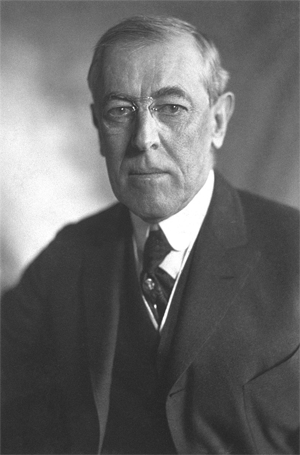

• Many major Progressive leaders, such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, held racist views that limited their reform efforts to white, middle-class Americans.

• Many Progressives favored disenfranchising black voters in South.

• The American Federation of Labor (AFL) expressed a significant amount of racism during the Progressive Era.

• This rise in AFL prominence allowed it to not only strictly regulate its own members, but also to influence the development of anti- immigration policy over the course of the early twentieth century.

• Generally the AFL viewed women and black workers as competition, as strikebreakers, or as an unskilled labor reserve that kept wages low.

• The AFL supported the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and then became avid in supporting further anti- immigrant labor legislation in 1921 and 1924.

-- The Limits of Progressivism, by lumne, Boundless US History

The Progressive Era was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States that spanned the 1890s to the 1920s.[1] The main objectives of the Progressive movement were addressing problems caused by industrialization, urbanization, immigration, and political corruption. The movement primarily targeted political machines and their bosses. By taking down these corrupt representatives in office, a further means of direct democracy would be established. They also sought regulation of monopolies (trustbusting) and corporations through antitrust laws, which were seen as a way to promote equal competition for the advantage of legitimate competitors. They also advocated for new government roles and regulations, and new agencies to carry out those roles, such as the FDA.

Many progressives supported prohibition of alcoholic beverages, ostensibly to destroy the political power of local bosses based in saloons, but others out of a religious motivation.[2] At the same time, women's suffrage was promoted to bring a "purer" female vote into the arena.[3] A third theme was building an Efficiency Movement in every sector that could identify old ways that needed modernizing, and bring to bear scientific, medical and engineering solutions; a key part of the efficiency movement was scientific management, or "Taylorism". In Michael McGerr's book A Fierce Discontent, Jane Addams stated that she believed in the necessity of "association" of stepping across the social boundaries of industrial America.[4]

Many activists joined efforts to reform local government, public education, medicine, finance, insurance, industry, railroads, churches, and many other areas. Progressives transformed, professionalized and made "scientific" the social sciences, especially history,[5] economics,[6] and political science.[7] In academic fields, the day of the amateur author gave way to the research professor who published in the new scholarly journals and presses. The national political leaders included Republicans Theodore Roosevelt, Robert M. La Follette Sr. and Charles Evans Hughes, and Democrats William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson and Al Smith. Leaders of the movement also existed far from presidential politics: Jane Addams, Grace Abbott, Edith Abbott and Sophonisba Breckinridge were among the most influential non-governmental Progressive Era reformers.

Initially the movement operated chiefly at the local level, but later it expanded to the state and national levels. Progressives drew support from the middle class, and supporters included many lawyers, teachers, physicians, ministers, and business people.[8] Some Progressives strongly supported scientific methods as applied to economics, government, industry, finance, medicine, schooling, theology, education, and even the family. They closely followed advances underway at the time in Western Europe[9] and adopted numerous policies, such as a major transformation of the banking system by creating the Federal Reserve System in 1913[10] and the arrival of cooperative banking in the US with the founding of the first credit union in 1908.[11] Reformers felt that old-fashioned ways meant waste and inefficiency, and eagerly sought out the "one best system".[12][13]

Originators of progressive ideals and efforts

Certain key groups of thinkers, writers, and activists played key roles in creating or building the movements and ideas that came to define the shape of the Progressive Era.

Muckraking: exposing corruption

Further information: Muckraker and Mass media and American politics

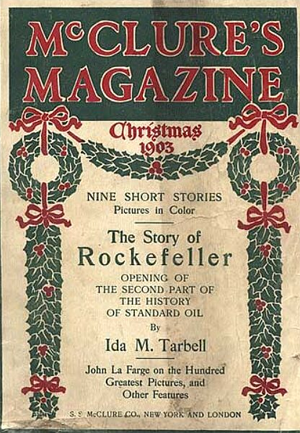

McClure's Christmas 1903 cover

Magazines experienced a boost in popularity in 1900, with some attaining circulations in the hundreds of thousands of subscribers. In the beginning of the age of Mass media, the rapid expansion of national advertising led the cover price of popular magazines to fall sharply to about 10 cents, lessening the financial barrier to consume them.[14] Another factor contributing to the dramatic upswing in magazine circulation was the prominent coverage of corruption in politics, local government and big business, particularly by journalists and writers who became known as muckrakers. They wrote for popular magazines to expose social and political sins and shortcomings. Relying on their own investigative journalism, muckrakers often worked to expose social ills and corporate and political corruption. Muckraking magazines, notably McClure's, took on corporate monopolies and crooked political machines while raising public awareness of chronic urban poverty, unsafe working conditions, and social issues like child labor.[15] Most of the muckrakers wrote nonfiction, but fictional exposés often had a major impact as well, such as those by Upton Sinclair.[16] In his 1906 novel The Jungle Sinclair exposed the unsanitary and inhumane practices of the meat packing industry. He quipped, "I aimed at the public's heart and by accident I hit it in the stomach," as readers demanded and got the Pure Food and Drug Act.[17]

The journalists who specialized in exposing waste, corruption, and scandal operated at the state and local level, like Ray Stannard Baker, George Creel, and Brand Whitlock. Others such as Lincoln Steffens exposed political corruption in many large cities; Ida Tarbell is famed for her criticisms of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company. In 1906, David Graham Phillips unleashed a blistering indictment of corruption in the U.S. Senate. Roosevelt gave these journalists their nickname when he complained they were not being helpful by raking up all the muck.[18][19]

Modernization

Further information: Efficiency Movement

The Progressives were avid modernizers, with a belief in science and technology as the grand solution to society's flaws. They looked to education as the key to bridging the gap between their present wasteful society and technologically enlightened future society. Characteristics of Progressivism included a favorable attitude toward urban-industrial society, belief in mankind's ability to improve the environment and conditions of life, belief in an obligation to intervene in economic and social affairs, a belief in the ability of experts and in the efficiency of government intervention.[20][21] Scientific management, as promulgated by Frederick Winslow Taylor, became a watchword for industrial efficiency and elimination of waste, with the stopwatch as its symbol.[22][23]

Philanthropy

The number of rich families climbed exponentially, from 100 or so millionaires in the 1870s, to 4000 in 1892 and 16,000 in 1916. Many subscribed to Andrew Carnegie's credo outlined in The Gospel of Wealth that said they owed a duty to society that called for philanthropic giving to colleges, hospitals, medical research, libraries, museums, religion and social betterment.[24]

In the early 20th century, American philanthropy matured, with the development of very large, highly visible private foundations created by Rockefeller, and Carnegie. The largest foundations fostered modern, efficient, business-oriented operations (as opposed to "charity") designed to better society rather than merely enhance the status of the giver. Close ties were built with the local business community, as in the "community chest" movement.[25] The American Red Cross was reorganized and professionalized.[26] Several major foundations aided the blacks in the South, and were typically advised by Booker T. Washington. By contrast, Europe and Asia had few foundations. This allowed both Carnegie and Rockefeller to operate internationally with powerful effect.[27]

The middle class theory

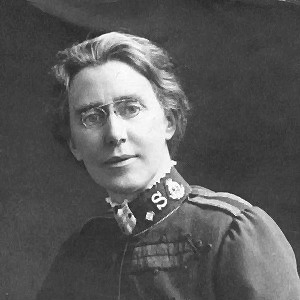

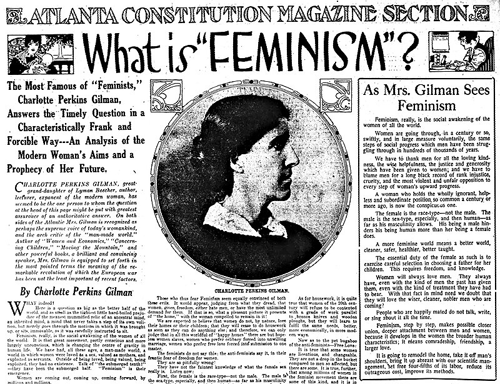

Charlotte Perkins Gilman (pictured) wrote these articles about feminism for the Atlanta Constitution, published on December 10, 1916.

A hallmark group of the Progressive Era, the middle class became the driving force behind much of the thought and reform that took place in this time. With an increasing disdain for the upper class and aristocracy of the time, the middle class is characterized by their rejection of the individualistic philosophy of the Upper ten.[28] They had a rapidly growing interest in the communication and role between classes, those of which are generally referred to as the upper class, working class, farmers, and themselves.[29] Along these lines, the founder of Hull-House, Jane Addams, coined the term "association" as a counter to Individualism, with association referring to the search for a relationship between the classes.[30] Additionally, the middle class (most notably women) began to move away from prior Victorian era domestic values. Divorce rates increased as women preferred to seek education and freedom from the home.[quantify] Victorianism was pushed aside in favor of the rise of the Progressives.[31]

Individual activists' efforts and works

Politicians and government officials

• President Theodore Roosevelt was a leader of the Progressive movement, and he championed his "Square Deal" domestic policies, promising the average citizen fairness, breaking of trusts, regulation of railroads, and pure food and drugs. He made conservation a top priority and established many new national parks, forests, and monuments intended to preserve the nation's natural resources. In foreign policy, he focused on Central America where he began construction of the Panama Canal. He expanded the army and sent the Great White Fleet on a world tour to project the United States' naval power around the globe. His successful efforts to broker the end of the Russo-Japanese War won him the 1906 Nobel Peace Prize. He avoided controversial tariff and money issues. He was elected to a full term in 1904 and continued to promote progressive policies, some of which were passed in Congress. By 1906 he was moving to the left, advocating for some social welfare programs, and criticizing various business practices such as trusts. The leadership of the GOP in Congress moved to the right, as did his protege President William Howard Taft. Roosevelt broke bitterly with Taft in 1910, and also with Wisconsin's progressive leader Robert M. La Follette. Taft defeated Roosevelt for the 1912 Republican nomination and Roosevelt set up an entirely new Progressive Party. It called for a “New Nationalism” with active supervision of corporations, higher taxes, and unemployment and old-age insurance. He supported voting rights for women, but was silent on civil rights for blacks, who remained in the regular Republican fold. He lost and his new party collapsed, as conservatism dominated the GOP for decades to come. Biographer William Harbaugh argues:

In foreign affairs, Theodore Roosevelt’s legacy is judicious support of the national interest and promotion of world stability through the maintenance of a balance of power; creation or strengthening of international agencies, and resort to their use when practicable; and implicit resolve to use military force, if feasible, to foster legitimate American interests. In domestic affairs, it is the use of government to advance the public interest. “If on this new continent,” he said, “we merely build another country of great but unjustly divided material prosperity, we shall have done nothing.”[32]

• President Woodrow Wilson introduced a comprehensive program of domestic legislation at the outset of his administration, something no president had ever done before.[33] He had four major domestic priorities: the conservation of natural resources, banking reform, tariff reduction, and equal access to raw materials, which would be accomplished in part through the regulation of trusts.[34] Though foreign affairs would increasingly dominate his presidency starting in 1915, Wilson's first two years in office largely focused on the implementation of his New Freedom domestic agenda.[35]

Wilson presided over the passage of his progressive New Freedom domestic agenda. His first major priority was the passage of the Revenue Act of 1913, which lowered tariffs and implemented a federal income tax. Later tax acts implemented a federal estate tax and raised the top income tax rate to 77 percent. Wilson also presided over the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, which created a central banking system in the form of the Federal Reserve System. Two major laws, the Federal Trade Commission Act and the Clayton Antitrust Act, were passed to regulate business and prevent monopolies. Wilson did not support civil rights and did not object to accelerating segregate of federal employees. In World War I he made internationalism a key element of the progressive outlook, as expressed in his Fourteen Points and the League of Nations--an ideal called Wilsonianism.[36][37]

• Charles Evans Hughes, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, played a key role in upholding many reforms, tending to align with Oliver Wendell Holmes. He voted to uphold state laws providing for minimum wages, workmen's compensation, and maximum work hours for women and children.[38] He also wrote several opinions upholding the power of Congress to regulate interstate commerce under the Commerce Clause. His majority opinion in Baltimore & Ohio Railroad vs. Interstate Commerce Commission upheld the right of the federal government to regulate the hours of railroad workers.[39] His majority opinion in the 1914 Shreveport Rate Case upheld the Interstate Commerce Commission's decision to void discriminatory railroad rates imposed by the Railroad Commission of Texas. The decision established that the federal government could regulate intrastate commerce when it affected interstate commerce, though Hughes avoided directly overruling the 1895 case of United States v. E. C. Knight Co..[40]

• Gifford Pinchot was an American forester and politician. Pinchot served as the first Chief of the United States Forest Service from 1905 until 1910, and was the 28th Governor of Pennsylvania, serving from 1923 to 1927, and again from 1931 to 1935. He was a member of the Republican Party for most of his life, though he also joined the Progressive Party for a brief period. Pinchot is known for reforming the management and development of forests in the United States and for advocating the conservation of the nation's reserves by planned use and renewal.[41] He called it "the art of producing from the forest whatever it can yield for the service of man." Pinchot coined the term conservation ethic as applied to natural resources. Pinchot's main contribution was his leadership in promoting scientific forestry and emphasizing the controlled, profitable use of forests and other natural resources so they would be of maximum benefit to mankind.[41] He was the first to demonstrate the practicality and profitability of managing forests for continuous cropping. His leadership put conservation of forests high on America's priority list.[42]

Authors and journalists

• Upton Sinclair was an American writer who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in several genres. Sinclair's work was well known and popular in the first half of the 20th century, and he won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1943. In 1906, Sinclair acquired particular fame for his classic muck-raking novel The Jungle, which exposed labor and sanitary conditions in the U.S. meatpacking industry, causing a public uproar that contributed in part to the passage a few months later of the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act.[43] In 1919, he published The Brass Check, a muck-raking exposé of American journalism that publicized the issue of yellow journalism and the limitations of the "free press" in the United States. Four years after publication of The Brass Check, the first code of ethics for journalists was created.[44]

He is well remembered for the line: "It is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends upon his not understanding it."[45] He used this line in speeches and the book about his campaign for governor as a way to explain why the editors and publishers of the major newspapers in California would not treat seriously his proposals for old age pensions and other progressive reforms.[46] Many of his novels can be read as historical works. Sinclair describes the world of industrialized America from both the working man's and the industrialist's points of view. Novels such as King Coal (1917), The Coal War (published posthumously), Oil! (1927), and The Flivver King (1937) describe the working conditions of the coal, oil, and auto industries at the time.

• Ida Tarbell, a writer and lecturer, was one of the leading muckrakers and pioneered investigative journalism.[47] Tarbell is best known for her 1904 book, The History of the Standard Oil Company. The book was published as a series of articles in McClure's Magazine from 1902 to 1904. It has been called a "masterpiece of investigative journalism", by historian J. North Conway,[48] as well as "the single most influential book on business ever published in the United States" by historian Daniel Yergin.[49] The work would contribute to the dissolution of the Standard Oil monopoly and helped usher in the Hepburn Act of 1906, the Mann-Elkins Act, the creation of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Clayton Antitrust Act.

• Lincoln Steffens was another investigative journalist and one of the leading muckrakers. He launched a series of articles in McClure's, called Tweed Days in St. Louis,[50] that would later be published together in a book titled The Shame of the Cities. He is remembered for investigating corruption in municipal government in American cities and leftist values.

Researchers and intellectual theorists

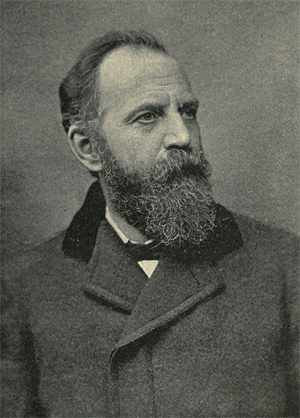

• Henry George was an American political economist and journalist. His writing was immensely popular in the 19th century, and sparked several reform movements. His writings also inspired the economic philosophy known as Georgism, based on the belief that people should own the value they produce themselves, but that the economic value derived from land (including natural resources) should belong equally to all members of society. His most famous work, Progress and Poverty (1879), sold millions of copies worldwide, probably more than any other American book before that time. The treatise investigates the paradox of increasing inequality and poverty amid economic and technological progress, the cyclic nature of industrialized economies, and the use of rent capture such as land value tax and other anti-monopoly reforms as a remedy for these and other social problems.

The mid-20th century labor economist and journalist George Soule wrote that George was "By far the most famous American economic writer," and "author of a book which probably had a larger world-wide circulation than any other work on economics ever written."[51]

• Herbert David Croly was an intellectual leader of the progressive movement as an editor, political philosopher and a co-founder of the magazine The New Republic in early twentieth-century America. His political philosophy influenced many leading progressives including Theodore Roosevelt, as well as his close friends Judge Learned Hand and Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter.[52] His 1909 book The Promise of American Life looked to the constitutional liberalism as espoused by Alexander Hamilton, combined with the radical democracy of Thomas Jefferson.[53] The book was one of the most influential in American political history, shaping the ideas of many intellectuals and political leaders. It also influenced the later New Deal. Calling themselves "The New Nationalists", Croly and Walter Weyl sought to remedy the relatively weak national institutions with a strong federal government. He promoted a strong army and navy and attacked pacifists who thought democracy at home and peace abroad was best served by keeping America weak.

Croly was one of the founders of modern liberalism in the United States, especially through his books, essays and a highly influential magazine founded in 1914, The New Republic. In his 1914 book Progressive Democracy, Croly rejected the thesis that the liberal tradition in the United States was inhospitable to anti-capitalist alternatives. He drew from the American past a history of resistance to capitalist wage relations that was fundamentally liberal, and he reclaimed an idea that progressives had allowed to lapse—that working for wages was a lesser form of liberty. Increasingly skeptical of the capacity of social welfare legislation to remedy social ills, Croly argued that America's liberal promise could be redeemed only by syndicalist reforms involving workplace democracy. His liberal goals were part of his commitment to American republicanism.[54]

• Thorstein Veblen was an American economist and sociologist, who during his lifetime emerged as a well-known critic of capitalism. In his best-known book, The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Veblen coined the concept of conspicuous consumption and conspicuous leisure. Historians of economics regard Veblen as the founding father of the institutional economics school. Contemporary economists still theorize Veblen's distinction between "institutions" and "technology", known as the Veblenian dichotomy. As a leading intellectual, Veblen attacked production for profit. His emphasis on conspicuous consumption greatly influenced economists who engaged in non-Marxist critiques of capitalism and of technological determinism.

Activists and organizers

• Mary G. Harris Jones,[55][56] known as Mother Jones, was an Irish-born American schoolteacher and dressmaker who became a prominent organized labor representative, community organizer, and activist. She helped coordinate major strikes and co-founded the Industrial Workers of the World. Jones worked as a teacher and dressmaker, but after her husband and four children all died of yellow fever in 1867 and her dress shop was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, she became an organizer for the Knights of Labor and the United Mine Workers union. From 1897 onwards, she was known as Mother Jones. In 1902, she was called "the most dangerous woman in America" for her success in organizing mine workers and their families against the mine owners. In 1903, to protest the lax enforcement of the child labor laws in the Pennsylvania mines and silk mills, she organized a children's march from Philadelphia to the home of President Theodore Roosevelt in New York.

Societal reformers and activists

• Jane Addams was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker,[57][58] sociologist,[59] public administrator[60][61] and author. She was a notable figure in the history of social work and women's suffrage in the United States and an advocate for world peace.[62] She co-founded Chicago's Hull House, one of America's most famous settlement houses. In 1920, she was a co-founder for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).[63] In 1931, she became the first American woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and is recognized as the founder of the social work profession in the United States.[64] Maurice Hamington considered her a radical pragmatist and the first woman "public philosopher" in the United States.[65] In the 1930s, she was the best-known female public figure in the United States. .[66]

Key ideas and issues

Government reform

Disturbed by the waste, inefficiency, stubbornness, corruption, and injustices of the Gilded Age, the Progressives were committed to changing and reforming every aspect of the state, society and economy. Significant changes enacted at the national levels included the imposition of an income tax with the Sixteenth Amendment, direct election of Senators with the Seventeenth Amendment, Prohibition with the Eighteenth Amendment, election reforms to stop corruption and fraud, and women's suffrage through the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[67]

A main objective of the Progressive Era movement was to eliminate corruption within the government. They made it a point to also focus on family, education, and many other important aspects that still are enforced today. The most important political leaders during this time were Theodore Roosevelt, Robert M. La Follette Sr., Charles Evans Hughes, and Herbert Hoover. Some democratic leaders included William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson, and Al Smith.[68]

This movement targeted the regulations of huge monopolies and corporations. This was done through antitrust laws to promote equal competition amongst every business. This was done through the Sherman Act of 1890, the Clayton Act of 1914, and the Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914.[68]

Family and food

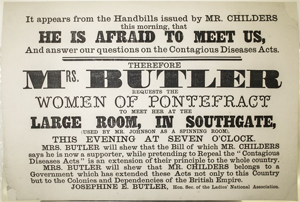

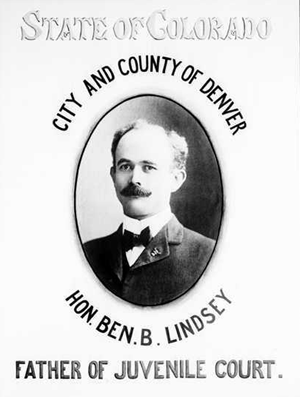

Colorado judge Ben Lindsey, a pioneer in the establishment of juvenile court systems

Progressives believed that the family was the foundation stone of American society, and the government, especially municipal government, must work to enhance the family.[69] Local public assistance programs were reformed to try to keep families together. Inspired by crusading Judge Ben Lindsey of Denver, cities established juvenile courts to deal with disruptive teenagers without sending them to adult prisons.[70][71]

During the progressive era more women took work outside the home. For the working class this work was often as a domestic servant. Yet working or not women were expected to perform all the cooking and cleaning. This "affected female domestics' experiences of their homes, workplaces, and possessions, While the male household members, comforted by the smells of home cooking, fresh laundry, and soaped floors, would have seen home as a refuge from work, women would have associated these same smells with the labor that they expended to maintain order."[72] With increases in technology some of this work became easier. The "introduction of gas, indoor plumbing, electricity and garbage pickup had a significant impact on the homes and the women who were responsible for maintaining them."[73] With the introduction of new methods of heating and lighting the home allowed for use of space once used for storage to become living spaces.[73] Women were targeted by advertisements for many different products once produced at home. These products were anything from mayonnaise, soda, or canned vegetables.[74]

The purity of food, milk and drinking water became a high priority in the cities. At the state and national levels new food and drug laws strengthened urban efforts to guarantee the safety of the food system. The 1906 federal Pure Food and Drug Act, which was pushed by drug companies and providers of medical services, removed from the market patent medicines that had never been scientifically tested.[75]

With the decrease in standard working hours, urban families had more leisure time. Many spent this leisure time at movie theaters. Progressives advocated for censorship of motion pictures as it was believed that patrons (especially children) viewing movies in dark, unclean, potentially unsafe theaters, might be negatively influenced in witnessing actors portraying crimes, violence, and sexually suggestive situations. Progressives across the country influenced municipal governments of large urban cities, to build numerous parks where it was believed that leisure time for children and families could be spent in a healthy, wholesome environment, thereby fostering good morals and citizenship.[76]

Labor policy and unions

Labor unions, especially the American Federation of Labor (AFL), grew rapidly in the early 20th century, and had a Progressive agenda as well. After experimenting in the early 20th century with cooperation with business in the National Civic Federation, the AFL turned after 1906 to a working political alliance with the Democratic party. The alliance was especially important in the larger industrial cities. The unions wanted restrictions on judges who intervened in labor disputes, usually on the side of the employer. They finally achieved that goal with the Norris–La Guardia Act of 1932.[77]

By the turn of the century, more and more small businesses were getting fed up with the way that they were treated compared to the bigger businesses. It seemed that the "Upper Ten" were turning a blind-eye to the smaller businesses, cutting corners wherever they could to make more profit. The big businesses would soon find out that the smaller businesses were starting to gain ground over them, so they became unsettled as described; "Constant pressure from the public, labor organizations, small business interests, and federal and state governments forced the corporate giants to engage in a balancing act."[78] Now that all of these new regulations and standards were being enacted, the big business would now have to stoop to everyone's level, including the small businesses. The big businesses would soon find out that in order to succeed they would have to band together with the smaller businesses to be successful, kind of a "Yin and Yang" effect.

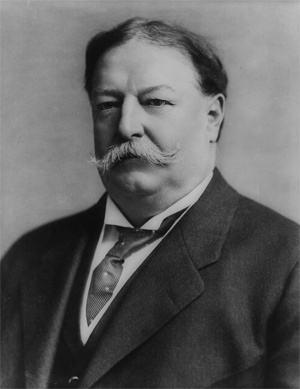

United States President William Howard Taft signed the March 4, 1913, bill (the last day of his presidency), establishing the Department of Labor as a Cabinet-level department, replacing the previous Department of Commerce and Labor. William B. Wilson was appointed as the first Secretary of Labor on March 5, 1913, by President Wilson.[79] In October 1919, Secretary Wilson chaired the first meeting of the International Labour Organization even though the U.S. was not yet a member.[80]

In September 1916, the Federal Employees' Compensation Act introduced benefits to workers who are injured or contract illnesses in the workplace. The act established an agency responsible for federal workers’ compensation, which was transferred to the Labor Department in the 1940s and has become known as the Office of Workers' Compensation Programs.[81]

Civil rights issues

Women

Main article: History of women in the United States § Progressive era: 1900–1940

Across the nation, middle-class women organized on behalf of social reforms during the Progressive Era. Using the language of municipal housekeeping women were able to push such reforms as prohibition, women's suffrage, child-saving, and public health.

Middle class women formed local clubs, which after 1890 were coordinated by the General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC). Historian Paige Meltzer puts the GFWC in the context of the Progressive Movement, arguing that its policies:

built on Progressive-era strategies of municipal housekeeping. During the Progressive era, female activists used traditional constructions of womanhood, which imagined all women as mothers and homemakers, to justify their entrance into community affairs: as "municipal housekeepers," they would clean up politics, cities, and see after the health and well being of their neighbors. Donning the mantle of motherhood, female activists methodically investigated their community's needs and used their "maternal" expertise to lobby, create, and secure a place for themselves in an emerging state welfare bureaucracy, best illustrated perhaps by clubwoman Julia Lathrop's leadership in the Children's Bureau. As part of this tradition of maternal activism, the Progressive-era General Federation supported a range of causes from the pure food and drug administration to public health care for mothers and children, to a ban on child labor, each of which looked to the state to help implement their vision of social justice.[82]

Women during the Progressive Era were often unhappy and faked enjoyment in their married heterosexual relationships.[83] Middle class women known for calling out change, specifically in cities like New York City, questioned the rethinking of marriage and sexuality. Women craved more sexual freedom following the sexually repressive and restrictive Victorian Era.[83] Dating in relationships became a new way of courting during the Progressive Era and moved the United States into a more romantic way of viewing marriage and relationships.[83] Within more engagements and marriages, both parties would exchange love notes as a way to express their sexual feelings. The divide between aggressive passionate love associated usually with men and a women's more spiritual romantic love became apparent in the middle-class as women were judged on how they should be respected based on how they expressed these feelings.[83] So, frequently women expressed passionless emotions towards love as a way to establish status among men in the middle class.[83]

Women's Suffrage

Main article: National American Woman Suffrage Association

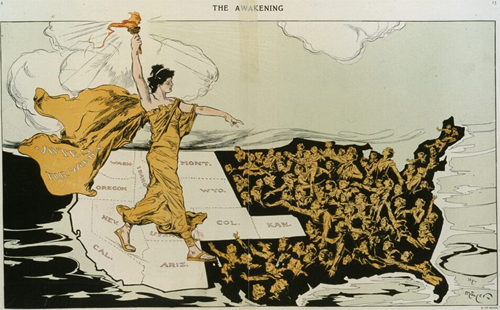

"The Awakening": Suffragists were successful in the West; their torch awakens the women struggling in the East and South in this cartoon by Hy Mayer in Puck Feb. 20, 1915.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an American women's rights organization formed in May 1890 as a unification of the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). The NAWSA set up hundreds of smaller local and state groups, with the goal of passing woman suffrage legislation at the state and local level. The NAWSA was the largest and most important suffrage organization in the United States, and was the primary promoter of women's right to vote. Carrie Chapman Catt was the key leader in the early 20th century. Like AWSA and NWSA before it, the NAWSA pushed for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women's voting rights, and was instrumental in winning the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1920.[84][85] A breakaway group, the National Woman's Party, tightly controlled by Alice Paul, used civil disobedience to gain publicity and force passage of suffrage. Paul's members chained themselves to the White House fence in order to get arrested, then went on hunger strikes to gain publicity. While the British suffragettes stopped their protests in 1914 and supported the British war effort, Paul began her campaign in 1917 and was widely criticized for ignoring the war and attracting radical anti-war elements.[86]

Race relations

Across the South, black communities developed their own Progressive reform projects.[87][88] Typical projects involved upgrading schools, modernizing church operations, expanding business opportunities, fighting for a larger share of state budgets, and engaging in legal action to secure equal rights.[89] Reform projects were especially notable in rural areas, where the great majority of Southern blacks lived.[90]

Rural blacks were heavily involved in environmental issues, in which they developed their own traditions and priorities.[91][92] George Washington Carver (1860–1943) was a leader in promoting environmentalism, and was well known for his research projects, particularly those involving agriculture.[93]

Although there were some achievements that improved conditions for African Americans and other non-white minorities, the Progressive Era was the nadir of American race relations. While white Progressives in principle believed in improving conditions for minority groups, there were wide differences in how this was to be achieved. Some, such as Lillian Wald, fought to alleviate the plight of poor African Americans. Many, though, were concerned with enforcing, not eradicating, racial segregation. In particular, the mixing of black and white pleasure-seekers in "black-and-tan" clubs troubled Progressive reformers.[94] The Progressive ideology espoused by many of the era attempted to correct societal problems created by racial integration following the Civil War by segregating the races and allowing each group to achieve its own potential. That is to say that most Progressives saw racial integration as a problem to be solved, rather than a goal to be achieved.[95][96][97] As white progressives sought to help the white working-class, clean-up politics, and improve the cities, the country instated the system of racial segregation known as Jim Crow.[98]

One of the most impacting issues African Americans had to face during the Progressive Era was the right to vote. By the beginning of the 20th century, African Americans were "disfranchised", while in the years prior to this, the right to vote was guaranteed to "freedmen" through the Civil Rights Act of 1870.[99] Southern whites wanted to rid of the political influence of the black vote, citing "that black voting meant only corruption of elections, incompetence of government, and the engendering of fierce racial antagonisms."[99] Progressive whites found a "loophole" to the 15th Amendment's prohibition of denying one the right to vote due to race through the Grandfather Clause.[99] This allowed for the creation of "tests" that would essentially be designed in a way that would allow for whites to pass them but not African Americans or any other persons of color.[99] Actions such as these from whites of the Progressive Era are some of the many that tied into the Progressive goal, as historian Michael McGerr states, "to segregate society."[100]

Legal historian Herbert Hovenkamp argues that while many early progressives inherited the racism of Jim Crow, as they begin to innovate their own ideas, they would embrace behaviorism, cultural relativism and marginalism which stress environmental influences on humans rather than biological inheritance. He states that ultimately progressives "were responsible for bringing scientific racism to an end".[101]