Part 2 of 2

Tamil language and writingMain article: Periyar E. V. Ramasamy and Tamil grammar

Periyar claimed that Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, and Kannada came from the same mother language of Old Tamil. He explained that the Tamil language is called by four different names since it is spoken in four different Dravidian states. Nevertheless, current understanding of Dravidian languages contradicts such claims. For example, the currently known classification of Dravidian languages provides the following distinct classes: Southern (including Tamil–Malayalam, Kannada and Tulu); Central (including Telugu–Kui and Kolami–Parji); and, Northern (including Kurukh–Malto and Brahui).

With relation to writing, Periyar stated that using the Tamil script about the arts, which are useful to the people in their life and foster knowledge, talent and courage, and propagating them among the masses, will enlighten the people. Further, he explained that it will enrich the language, and thus it can be regarded as a zeal for Tamil.[72] Periyar also stated that if words of North Indian origin (Sanskrit) are removed from Telugu, Kannada, and Malayalam, only Tamil will be left. On the Brahmin usage of Tamil, he stated that the Tamil spoken by the Andhras and the Malayali people was far better than the Tamil spoken by the Brahmins. Periyar believed that Tamil language will make the Dravidian people unite under the banner of Tamil culture, and that it will make the Kannadigas, Andhras and the Malayalees be vigilant. With regards to a Dravidian alliance under a common umbrella language, Periyar stated that "a time will come for unity. This will go on until there is an end to the North Indian domination. We shall reclaim an independent sovereign state for us".[73]

At the same time, Periyar was also known to have made controversial remarks on the Tamil language and people from time to time. On one occasion, he referred to the Tamil people as "barbarians"[74] and the Tamil language as the "language of barbarians".[75][74][76][77][78] However, Anita Diehl explains that Periyar made these remarks on Tamil because it had no respective feminine verbal forms.[33] But Anita Diehl's explanation doesn't match with Periyar's own explanation. Periyar himself explained reasons many times in his speeches and writings, for instance, an excerpt from his book Thamizhum, Thamizharum(Tamil and Tamil people) reads, "I say Tamil as barbarian language. Many get angry with me for saying so. But no one ponders over why I say so. They say Tamil is a 3,000 to 4,000 years-old language and they boast about this. Precisely that is what the reason why I call Tamil as barbarian language. People should understand the term primitive and barbarism. What was the status of people living 4,000 years ago and now? We are just blindly sticking to old glories. No one has come forward to reform Tamil language and work for its growth."[79]

Periyar's ideas on Tamil alphabet reforms included those such as the reasons for the vowel 'ஈ' (i) having a cursive and looped representation of the short form 'இ' (I).[clarification needed] In stone inscriptions from 400 or 500 years ago, many Tamil letters are found in other shapes. As a matter of necessity and advantage to cope with printing technology, Periyar thought that it was sensible to change a few letters, reduce the number of letters, and alter a few signs. He further explained that the older and more divine a language and its letters were said to be, the more they needed reform. Because of changes brought about by means of modern transport and international contact, and happenings that have attracted words and products from many countries, foreign words and their pronunciations have been assimilated into Tamil quite easily. Just as a few compound characters have separate signs to indicate their length as in ' கா ', ' கே ' (kA:, kE:), Periyar questioned why other compound characters like ' கி ', ' கீ ', 'கு ', ' கூ ' (kI, ki:, kU, ku:) (indicated integrally as of now), shouldn't also have separate signs. Further, changing the shape of letters, creating new symbols and adding new letters and similarly, dropping those that are redundant, were quite essential according to Periyar. Thus, the glory and excellence of a language and its script depend on how easily they can be understood or learned and on nothing else"[33]

Thoughts on ThirukkuralMain article: Thirukkural

Periyar hailed the Thirukkural as a valuable scripture which contained many scientific and philosophical truths. He also praised the secular nature of the work. Periyar praised Thiruvalluvar for his description of God as a formless entity with only positive attributes. He also suggested that one who reads the Thirukkural will become a Self-respecter, absorbing knowledge in politics, society, and economics. According to him, though certain items in this ancient book of ethics may not relate to today, it permitted such changes for modern society.[80]

On caste, he believed that the Kural illustrates how Vedic laws of Manu were against the Sudras and other communities of the Dravidian race. On the other hand, Periyar opined that the ethics from the Kural was comparable to the Christian Bible. The Dravidar Kazhagam adopted the Thirukkural and advocated that Thiruvalluvar's Kural alone was enough to educate the people of the country.[80] One of Periyar's quotes on the Thirukkural from Veeramani's Collected Works of Periyar was "when Dravida Nadu (Dravidistan) was a victim to Indo-Aryan deceit, Thirukkural was written by a great Dravidian Thiruvalluvar to free the Dravidians".[80]

Periyar also asserted that due to the secular nature of Thirukkural, it has the capacity to be the common book of faith for all humanity and can be kept on par or above the holy books of all religions.

Self-determination of Dravida NaduMain article: Dravida Nadu

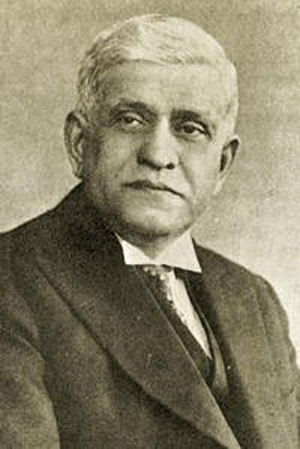

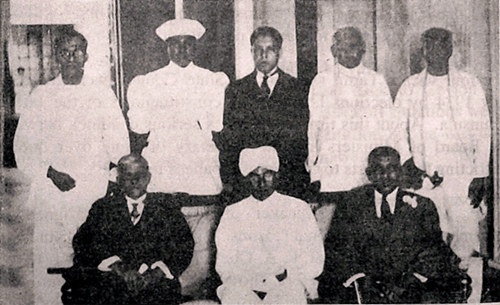

Periyar with Muhammad Ali Jinnah and B. R. Ambedkar

Periyar with Muhammad Ali Jinnah and B. R. AmbedkarThe Dravidian-Aryan conflict was believed to be a continuous historical phenomenon that started when the Aryans first set their foot in the Dravidian lands. Even a decade before the idea of separation appeared, Periyar stated that, "as long as Aryan religion, Indo-Aryan domination, propagation of Aryan Vedas and Aryan "Varnashrama" existed, there was need for a "Dravidian Progressive Movement" and a "Self-Respect Movement".[81] Periyar became very concerned about the growing North Indian domination over the south which appeared to him no different from foreign domination. He wanted to secure the fruits of labour of the Dravidians to the Dravidians, and lamented that fields such as political, economic, industrial, social, art, and spiritual were dominated by the north for the benefit of the North Indians. Thus, with the approach of independence from Britain, this fear that North India would take the place of Britain to dominate South India became more and more intense.[82]

Periyar was clear about the concept of a separate nation, comprising Tamil areas, that is part of the then existing Madras Presidency with adjoining areas into a federation guaranteeing protection of minorities, including religious, linguistic, and cultural freedom of the people. A separatist conference was held in June 1940 at Kanchipuram when Periyar released the map of the proposed Dravida Nadu, but failed to get British approval. On the contrary, Periyar received sympathy and support from people such as

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar and

Muhammad Ali Jinnah for his views on the Congress, and for his opposition to Hindi. They then decided to convene a movement to resist the Congress.[81][83]

The concept of Dravida Nadu was later modified down to Tamil Nadu.[84] This led to a proposal for a union of the Tamil people of not only South India but including those of Ceylon as well.[85] In 1953, Periyar helped to preserve Madras as the capital of Tamil Nadu, which later was the name he substituted for the more general Dravida Nadu.[86] In 1955 Periyar threatened to burn the national flag, but on Chief Minister Kamaraj's pledge that Hindi should not be made compulsory, he postponed the action.[33] In his speech of 1957 called Suthantara Tamil Nadu En? (Why an independent Tamil Nadu?), he criticised the Central Government of India, inducing thousands of Tamilians to burn the constitution of India. The reason for this action was that Periyar held the Government responsible for maintaining the caste system. After stating reasons for separation and turning down opinions against it, he closed his speech with a "war cry" to join and burn the map of India on 5 June. Periyar was sentenced to six months imprisonment for burning the Indian constitution.[87]

Advocacy of such a nation became illegal when separatist demands were banned by law in 1957. Regardless of these measures, a Dravida Nadu Separation Day was observed on 17 September 1960 resulting in numerous arrests.[88] However, Periyar resumed his campaign in 1968. He wrote an editorial on 'Tamil Nadu for Tamilians' in which he stated, that by nationalism only Brahmins had prospered and nationalism had been developed to abolish the rights of Tamils. He advocated that there was need to establish a Tamil Nadu Freedom Organization and that it was necessary to work towards it.[89]

Anti-Brahmanism vs. Anti-BrahminPeriyar was a radical advocate of anti-Brahmanism. Periyar's ideology of anti-Brahmanism is quite often confused as being anti-Brahmin. Even a non-Brahmin who supports inequality based on caste was seen as a supporter of brahmanism. Periyar called on both Brahmins and non-Brahmins to shun brahmanism.

In 1920, when the Justice Party came to power, Brahmins occupied about 70 percent[24][90] of the high level posts in the government. After reservation was introduced by the Justice Party, it reversed this trend, allowing non-Brahmins to rise in the government of the Madras Presidency.[90] Periyar, through the Justice Party, advocated against the imbalance of the domination of Brahmins who constituted only 3 percent[24][91] of the population, over government jobs, judiciary and the Madras University.[91] His Self-Respect Movement espoused rationalism and atheism and the movement had currents of anti-Brahminism.[92] Furthermore, Periyar stated that:

"Our Dravidian movement does not exist against the Brahmins or the Banias (a North Indian merchant caste). If anyone thinks so, I would only pity him. But we will not tolerate the ways in which Brahminism and the Bandiaism[clarification needed] is degrading Dravidanadu. Whatever support they may have from the government, neither myself nor my movement will be of cowardice".[93][94]

Periyar also criticised Subramanya Bharathi in the journal Ticutar for portraying Mother Tamil as a sister of Sanskrit in his poems:

"They say Bharati is an immortal poet.…Even if a rat dies in an akrakāram, they would declare it to be immortal. … of Tamilnadu praises him. Why should this be so? Supposedly because he sang fulsome praises of Tamil and Tamilnadu. What else could he sing? His own mother tongue, Sanskrit, has been dead for years. What other language did he know? He cannot sing in Sanskrit. … He says Tamilnadu is the land of Aryas."[95]

Comparisons with GandhiIn the Vaikom Satyagraha of 1924, Periyar and Gandhi ji both cooperated and confronted each other in socio-political action. Periyar and his followers emphasised the difference in point of view between Gandhi and himself on the social issues, such as fighting the Untouchability Laws and eradication of the caste system.

According to the booklet "Gandhi and Periyar", Periyar wrote in his paper Kudi Arasu in 1925, reporting on the fact that Gandhi was ousted from the Mahasabha because he opposed resolutions for the maintaining of caste and Untouchability Laws which would spoil his efforts to bring about Hindu-Muslim unity. From this, Gandhi learned the need for pleasing the Brahmins if anything was to be achieved.[96]

Peiryar in his references to Gandhi used opportunities to present Gandhi as, on principle, serving the interests of the Brahmins. In 1927, Periyar and Gandhi met at Bangalore to discuss this matter. The main difference between them came out when Periyar stood for the total eradication of Hinduism to which Gandhi objected saying that Hinduism is not fixed in doctrines but can be changed. In the Kudi Arasu, Periyar explained that:

"With all his good qualities, Gandhi did not bring the people forward from foolish and evil ways. His murderer was an educated man. Therefore nobody can say this is a time of high culture. If you eat poison, you will die. If electricity hits the body, you will die. If you oppose the Brahmin, you will die. Gandhi did not advocate the eradication of Varnasrama Dharma structure, but sees in it a task for the humanisation of society and social change possible within its structure. The consequence of this would be continued high-caste leadership. Gandhi adapted Brahmins to social change without depriving them of their leadership".[96]

Gandhi accepted karma in the sense that "the Untouchables reap the reward of their karma,[96] but was against discrimination against them using the revaluing term Harijans. As shown in the negotiations at Vaikom his methods for abolishing discrimination were: to stress on the orthodox, inhumane treatment of Untouchables; to secure voluntary lifting of the ban by changing the hearts of caste Hindus; and to work within a Hindu framework of ideas.[96]

On the Temple Entry issue, Gandhi never advocated the opening of Garbha Griha to Harijans in consequence of his Hindu belief. These sources which can be labelled "pro-Periyar" with the exception of M. Mahar and D.S. Sharma, clearly show that Periyar and his followers emphasised that Periyar was the real fighter for the removal of Untouchability and the true upliftment of Hairjans, whereas Gandhi was not. This did not prevent Periyar from having faith in Gandhi on certain matters.[96]

Religion and atheismMain article: Religious views of Periyar E. V. Ramasamy

Periyar was generally regarded[by whom?] as a pragmatic propagandist who attacked the evils of religious influence on society, mainly what he regarded as Brahmin domination. At a young age, he felt that some people used religion only as a mask to deceive innocent people and regarded it as his life's mission to warn people against superstitions and priests.[32] Anita Diehl explains that Periyar cannot be called an atheist philosopher. Periyar, however, qualified what the term "atheist" implies in his address on philosophy. He repudiated the term as without real sense: "…the talk of the atheist should be considered thoughtless and erroneous. The thing I call god... that makes all people equal and free, the god that does not stop free thinking and research, the god that does not ask for money, flattery and temples can certainly be an object of worship. For saying this much I have been called an atheist, a term that has no meaning".

Anita Diehl explains that Periyar saw faith as compatible with social equality and did not oppose religion itself.[97] In a book on revolution published in 1961, Periyar stated: "be of help to people. Do not use treachery or deceit. Speak the truth and do not cheat. That indeed is service to God."[98]

On Hinduism, Periyar believed that it was a religion with no distinctive sacred book (bhagawad gita) or origins, but an imaginary faith preaching the "superiority" of the Brahmins, the inferiority of the Shudras, and the untouchability of the Dalits (Panchamas).[43] Maria Misra, a lecturer at Oxford University, compares him to the philosophes, stating: "his contemptuous attitude to the baleful influence of Hinduism in Indian public life is strikingly akin to the anti-Catholic diatribes of the enlightenment philosophes".[99] In 1955 Periyar was arrested for his public action of burning pictures of Rama in public places as a symbolic protest against the Indo-Aryan domination and degradation of the Dravidian leadership according to the Ramayana epic.[100] Periyar also shoed images of Krishna and Rama, stating that they were Aryan gods that considered the Dravidian Shudras to be "sons of prostitutes".[101]

Periyar openly suggested to those who were marginalised within the Hindu communities to consider converting to other faiths such as Islam, Christianity, or Buddhism. On Islam, he stated how it was good for abolishing the disgrace in human relationship, based on one of his speeches to railway employees at Tiruchirapalli in 1947. Periyar also commended Islam for its belief in one invisible and formless God; for proclaiming equal rights for men and women; and for advocating social unity.[102]

At the rally in Tiruchi, Periyar said:

"Muslims are following the ancient philosophies of the Dravidians. The Arabic word for Dravidian religion is Islam. When Brahmanism was imposed in this country, it was Mohammad Nabi who opposed it, by instilling the Dravidian religion's policies as Islam in the minds of the people"[103]

Periyar viewed Christianity as similar to the monotheistic faith of Islam. He explained that the Christian faith says that there can be only one God which has no name or shape. Periyar took an interest in Martin Luther - both he and his followers wanted to liken him and his role to that of the European reformer. Thus Christian views, as expressed for example in The Precepts of Jesus (1820) by Ram Mohan Roy, had at least an indirect influence on Periyar.[104]

Apart from Islam and Christianity, Periyar also found in Buddhism a basis for his philosophy, though he did not accept that religion. It was again an alternative in the search for self-respect and the object was to get liberation from the discrimination of Hinduism.[105] Through Periyar's movement, Temple Entry Acts of 1924, 1931, and up to 1950 were created for non-Brahmins. Another accomplishment took place during the 1970s when Tamil replaced Sanskrit as the temple language in Tamil Nadu, while Dalits finally became eligible for priesthood.[33]

Controversies

Factionism in the Justice PartySee also: Justice Party (India)

When B. Munuswamy Naidu became the Chief Minister of Madras Presidency in 1930, he endorsed the inclusion of Brahmins in the Justice Party, saying:

So long as we exclude one community, we cannot as a political speak on behalf of, or claim to represent all the people of our presidency. If, as we hope, provincial autonomy is given to the provinces as a result of the reforms that may be granted, it should be essential that our Federation should be in a position to claim to be a truly representative body of all communities. What objection can there be to admit such Brahmins as are willing to subscribe to the aims and objects of our Federation? It may be that the Brahmins may not join even if the ban is removed. But surely our Federation will not thereafter be open to objection on the ground that it is an exclusive organisation.[106]

Though certain members supported the resolution, a faction in the Justice Party known as the "Ginger Group" opposed the resolution and eventually voted it down. Periyar, who was then an observer in the Justice Party, criticised Munuswamy Naidu, saying:

At a time when non-Brahmins in other parties were gradually coming over to the Justice Party, being fed up with the Brahmin's methods and ways of dealing with political questions, it was nothing short of folly to think of admitting him into the ranks of the Justice Party.[107]

This factionism continued until 1932 when Munuswamy Naidu stepped down as the Chief Minister of Madras and the Raja of Bobbili became the chief minister.[107]

Followers and influenceAfter the death of Periyar in 1973, conferences were held throughout Tamil Nadu for a week in January 1974. The same year Periyar's wife, Maniyammai, the new head of the Dravidar Kazhagam, set fire to the effigies of 'Rama', 'Sita' and 'Lakshmana' at Periyar Thidal, Madras. This was in retaliation to the Ramaleela celebrations where effigies of 'Ravana', 'Kumbakarna' and 'Indrajit' were burnt in New Delhi. For this act she was imprisoned. During the 1974 May Day meetings held at different places in Tamil Nadu, a resolution urging the Government to preserve 80 percent[24] of jobs for Tamils was passed. Soon after this, a camp was held at Periyar Mansion in Tiruchirapalli to train young men and women to spread the ideals of the Dravidar Kazhagam in rural areas.[24]

On Periyar's birthday on 17 September 1974, Periyar's Rationalist Library and Research Library and Research Institute was opened by the then Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi. This library contained Periyar's rationalist works, the manuscripts of Periyar and his recorded speeches.[68] Also during the same year Periyar's ancestral home in Erode, was dedicated as a commemoration building. On 20 February 1977, the opening function of Periyar Building in Madras was held. At the meeting which the Managing Committee of the Dravidar Kazhagam held, there on that day, it was decided to support the candidates belonging to the Janata Party, the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), and the Marxist Party during the General Elections.[24]

On 16 March 1978, Maniyammai died. The Managing Committee of the Dravidar Kazhagam elected K. Veeramani as General Secretary of the Dravidar Kazhagam on 17 March 1978. From then on, the Periyar-Maniyammai Educational and Charitable Society started the Periyar Centenary Women's Polytechnic at Thanjavur on 21 September 1980. On 8 May 1982, the College for Correspondence Education was started under the auspices of the Periyar Rationalist Propaganda Organization.[24]

Over the years, Periyar influenced Tamil Nadu's political party heads such as C.N. Annadurai[23] and M. Karunanidhi[108] of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam' (DMK), V. Gopalswamy[109][110] founder of the Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (MDMK), S. Ramadoss[111] founder of the Pattali Makkal Katchi (PMK), Thol. Thirumavalavan, founder of the Dalit Panthers of India (DPI), and Dravidar Kazhagam's K. Veeramani.[112] Nationally, Periyar is main ideological icon for India's third largest voted party, Bahujan Samaj Party[113][114] and its founder Kanshi Ram.[115] Other political figures influenced by Periyar were former Congress minister K. Kamaraj,[23] former Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh Mayawati.[116] Periyar's life and teachings have also influenced writers and poets such as Kavignar Inkulab, and Bharathidasan[117] including actors such as Kamal Haasan[118] and Sathyaraj.[119] Noted Tamil Comedian N. S. Krishnan was a close friend and follower of Periyar.[120][121]W. P. A. Soundarapandian Nadar was a close confidant of Periyar and encouraged Nadars to be a part of the Self-Respect Movement.[122][123] A writer from Uttar Pradesh, Lalai Singh Yadav translated Periyar's notable works into Hindi.[124][125][126]

In popular cultureMain article: Periyar (2007 film)

Sathyaraj and Khushboo Sundar starred in a government-sponsored film Periyar released in 2007. Directed by Gnana Rajasekaran, the film was screened in Malaysia on 1 May 2007 and was screened at the Goa International Film Festival in November that year.[127][128] Sathyaraj reprised his role as Periyar in the film Kalavadiya Pozhudugal directed by Thangar Bachan which released in 2017.[129]

References1. "About Periyar: A Biographical Sketch from 1879 to 1909". Dravidar Kazhagam. Archived from the original on 10 July 2005. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

2. "Statue wars: Who was Periyar and why does he trigger sentiment in Tamil Nadu?". The Economic Times. 7 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

3. Mehta, Vrajendra Raj; Thomas Pantham (2006). Political Ideas in Modern India: thematic explorations. Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7619-3420-2.

4. Arora, N.D.; S.S. Awasthy (2007). Political Theory and Political Thought. Har-Anand Publications: New Delhi. p. 425. ISBN 978-81-241-1164-2.

5. Thakurta, Paranjoy Guha; Shankar Raghuraman (2004). A Time of Coalitions: Divided We Stand. Sage Publications. New Delhi. p. 230. ISBN 0-7619-3237-2.

6. "Biography of Periyar E.V. Ramasami (1879–1973)". Barathidasan University. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

7. Kandasamy, W.B. Vansantha; Florentin Smarandache; K. Kandasamy (2005). Fuzzy and Neutrosophic Analysis of E.V. Ramasamy's Views on Untouchability. HEXIS: Phoenix. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-931233-00-2.

8. Saraswathi, p. 54.

9. Kandasamy (2005). NFuzzy and Neutrosophic Analysis of E.V. Ramasamy's Views on Untouchability. American Research Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-931233-00-2.

10. Pandian, J., (1987). Caste, Nationalism, and Ethnicity. Popular Prakashan Private Ltd.: Bombay. pp. 62, 64. ISBN 0861321367.

11. Chatterjee, Debi [1981] (2004) Up Against Caste: Comparative study of Ambedkar and Periyar. Rawat Publications: Chennai. pp. 40-42. ISBN 978-81-7033-860-4

12. "10 Reasons Why Ambedkar Would Not Get Along Very Well With 'Periyar'". Archivedfrom the original on 7 May 2016.

13. "Ramasamy Periyar | Tamil Nadu: Statue wars - Who was Periyar and why does he trigger sentiment in Tamil Nadu?" – via The Economic Times.

14. Sarkar, Sumit; Sarkar, Tanika (2008). Women and Social Reform in Modern India: A Reader. Indiana University Press. p. 401. ISBN 9780253352699.

15. Subramanian, Ajantha (2019). The Caste of Merit: Engineering Education in India. Harvard University Press. p. 100. ISBN 9780674987883.

16. Mahapatra, Subhasini (2001). Women and Politics. Rajat Publications. p. 211. ISBN 9788178800233.

17. Journal of Indian history, Volume 54, University of Allahabad, p. 175

18. Muthukumar, R. (2008). Periyar. Tamilnadu: Kizhaku Pathipakam. p. 15. ISBN 9788184930337.

19. Arooran, K. Nambi (1980). Tamil renaissance and Dravidian nationalism, 1905–1944. p. 152.

20. Vicuvanātan, Ī. Ca (1983). The political career of E.V. Ramasami: a study in the politics of Tamil Nadu, 1920–1949. p. 23.

21. Merchant Caste of Telugu Ancestry who descended from the migrant commanders of Vijayanagar Empire

22. Gopalakrishnan, p. 3.

23. "One Hundred Tamils of the 20th Century – Periyar E. V. Ramaswamy". TamilNation.org. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

24. Gopalakrishnan, pp. 50, 52.

25. Saraswathi, p. 6.

26. "E V Ramasamy Naickarin Marupakkam - M Venkatesan". tamilnation.co. Archivedfrom the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

27. "Periyar.org". periyar.org. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

28. Jeyaraman, B. (2013). Periyar: A Political Biography of E.V. Ramaswamy. Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788129132260. Retrieved 4 January2015.

29. "Tamil pride: What?s that? - Hindustan Times". hindustantimes.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

30. "FABO UK + About Dr Ambedkar". ambedkar.nspire.in. Archived from the original on 12 March 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

31. "About Periyar: Revolutionary Sayings". Dravidar Kazhagam. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

32. Veeramani 1992, Introduction – xi.

33. Diehl

34. Gopalakrishnan, pp. 14–17.

35. Diehl, pp. 22–24

36. Kent, David. "Periyar". ACA. Archived from the original on 15 June 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

37. Ravikumar (2 March 2006). "Re-reading Periyar". Countercurrents. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009.

38. Diehl, pp. 77-78

39. Saraswathi, p. 4.

40. Saraswathi, p. 19.

41. Diehl, p. 69.

42. Nalankilli, Thanjai (1 January 2003). "History: A Chronology of Anti-Hindi Agitations in Tamil Nadu and What the Future Holds". Tamil Tribune. Archived from the original on 30 July 2010. Retrieved 13 January 2003.

43. Saraswathi, pp. 118-119.

44. Saraswathi, pp. 88-89.

45. Diehl, p. 79.

46. International Tamil Language Foundation, (2000).Tirukkural/ The Handbok of Tamil Culture and Heritage. ITLF: Chicago, p. 1346. ISBN 978-0-9676212-0-3.

47. Diehl, p. 29.

48. Geetha, V.; S.V. Rajadurai, (1987). Towards a Non-Brahmin Millennium: From Iyothee Thass to Periyar. M. Sen for SAMYA: Calcutta, p. 481. ISBN 978-81-85604-37-4.

49. Richman, Paula (1991). The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia, Chapter 9: E. V. Ramasami's Reading of the Ramayana. University of California.

50. Gopalakrishnan, pp. 59-60.

51. Gopalakrishnan, pp. 45–49.

52. Veeramani 2005, p. 511.

53. Veeramani 2005, p. 504.

54. Saraswathi, p. 2.

55. Gopalakrishnan, p. 70.

56. Veeramani 1992, p. 22.

57. Veeramani 1992, p. 37.

58. Veeramani 1992, p. 65.

59. Veeramani 1992, p. 50.

60. Veeramani 2005, p. 570.

61. Veeramani 1992, p. 41

62. Gopalakrishnan, p. 32.

63. Veeramani 1992, p. 45.

64. Gopalakrishnan, p. 66.

65. Saraswathi, pp. 164-165.

66. Diehl, p. 68.

67. Saraswathi, p. 193.

68. Gopalakrishnan, pp. 60-61.

69. Diehl, p. 61.

70. Veeramani 2005, pp. 72-73.

71. Muthiah, S. (2008). Madras, Chennai: A 400-year Record of the First City of Modern India. Palaniappa Brothers. p. 357. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8.

72. Veeramani 2005, pp. 550–552.

73. Veeramani 2005, p. 503.

74. Raghavan, B. S. (9 October 2000). "Thanthai Periyar". The Hindu Business Line. Archived from the original on 23 November 2001. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

75. Ramaswamy, Cho. "E.V. Ramaswami Naicker and C.N. Annadurai". India Today: 100 people of the millennium. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

76. Sundaram, V. (6 March 2006). "The boy who gives a truer picture of 'Periyar'". News Today. Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

77. Dasgupta, Shankar (1975). Periyar E. V. Ramaswamy: A Proper Perspective D.G.S. ; [with an Introd. by Avvai. Sambandan]. Vairam Pathippagam. p. 24.

78. "Periyar's Otherside". thanthaiperiyar.org. Archived from the original on 21 January 2009. Retrieved 21 February 2009.

79. "Periyar: Both sides of the same coin". The New Indian Express.

80. Veeramani 2005, pp. 505–508.

81. Saraswathi, pp. 89-90.

82. Saraswathi, p. 95.

83. Dirks, Nicholas B. (2001). Castes of Mind: Colonialism and the Making of Modern India. Princeton University Press. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-691-08895-2.

84. Saraswathi, p. 98.

85. Ghurye, G.S. (1961). Caste, Class, and Occupation. Popular Book Depot: Bombay, p. 318.

86. Diehl, p. 76.

87. Diehl, p. 30

88. Bhaskaran, R. (1967). Sociology of Politics: Tradition of politics in India. Asia Publishing House: New York. p. 48.

89. Saraswathi, p. 9.

90. "Superiority in Numbers". Tehelka – The People's Paper. 2006. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2008.

91. "India and the Tamils" (PDF). Columbia University. 2006. Archived from the original(PDF) on 18 December 2008. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

92. Omvedt, Gail (2006). Dalit Visions: The Anti-caste Movement and the Construction on an Indian Identity. Orient Longman. p. 95. ISBN 978-81-250-2895-6.

93. Veeramani 2005, p. 495.

94. Rajasekharan, Gnana (30 April 2007). "Periyar was against Brahminism, not Brahmins". Rediff News. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

95. Ramaswamy, Sumathi (1997). Passions of the Tongue:Language Devotion in Tamil Nadu, 1891–1970. University of California.

96. Diehl, pp. 86–88

97. Diehl, p. 16

98. Diehl, p. 58

99. Misra, Maria (2008). Vishnu's Crowded Temple: India since the great rebellion. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-300-13721-7.

100. "About Periyar: A Biographical Sketch From 1950 to 1972". Dravidar Kazhagam. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

101. Veeramani 2005, pp. 218-219.

102. Diehl, p. 52

103. More, J. B. Prashant (2004). Muslim Identity, Print Culture, and the Dravidian Factor in Tamil Nadu. Orient Blackswan. p. 164. ISBN 978-81-250-2632-7.

104. Diehl, p. 92.

105. Saraswathi, p. 125.

106. Ralhan, p. 166

107. Ralhan, p. 197

108. "Periyar's philosophy relevant even today: Karunanidhi". The Hindu. 9 August 2007. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

109. "Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam". Marumalarchi Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam. Archived from the original on 24 May 2004. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

110. "POTA misuse will be main poll issue: Vaiko". The Hindu. 8 February 2004. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

111. "Busts of Marx, Periyar, Ambedkar opened". The Hindu. 19 September 2007. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

112. Veeramani, K. (1997). "International Convention for Solidarity with Eelam Tamils of Sri Lanka, 1997 – Nothing but, Genocide". TamilNation.org. Retrieved 17 December2008.[dead link]

113. "No law stops me from installing statues: Mayawati". Rediff. 16 March 2010.

114. "Ties between Mayawati and BJP hit new low as Kalyan Singh attacks her government". India Today. Retrieved 11 July2018.

115. "Kanshi Ram retains his fire despite 'Periyar' Mela's failure". India Today. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

116. IANS (28 July 2007). "Mayawati pursuing another dream – Periyar statue in Lucknow". DNA India. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2008.

117. Diehl, p. 81.

118. "'Periyar' Audio Launch". indiaglitz. 25 December 2006. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December2008.

119. "Sathyaraj gets Periyar Award". Cine South. 30 December 2006. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2008.

120. "Kalaivanar and his Contemporaries".

http://www.kalaivanar.com. 2009. Archived from the original on 23 August 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

121. Ravindran, Gopalan. "Remembering Theena Muna Kana, N.S.Krishnan and the Camouflaged Narrative Devices of Tamil Political Cinema". Wide Screen Journal. Archived from the original on 5 July 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

122. The Modernity of Tradition: Political Development in India. University of Chicago. 1984. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-226-73137-7.

123. Jaffrelot, Christophe (1984). India's Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in North India. Hurst & Co. p. 167. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8.

124. Ghosh, Avijit (31 October 2016). "These unsung Dalit writers fuelled BSP's culture politics". The Economic Times. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

125. "Lalai Singh Yadav: Fiery hero of rebel consciousness". Forward Press. 24 September 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2018.

126. "PERIYAR REMEMBERED IN PATNA".

http://www.modernrationalist.com. Retrieved 11 July2018.

127. "Periyar premiere in Malaysia". IndiaGlitz.com. 30 April 2007. Archived from the original on 28 February 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

128. "Periyar and Ammuvagiya Naan at the International Film Festival". Chennai365.com. 19 October 2007. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

129. "Kalavadiya Pozhudugal". Archived from the original on 22 July 2009. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

Cited sources• Diehl, Anita (1977). E. V. Ramaswami Naicker-Periar: A study of the influence of a personality in contemporary South India. Sweden: Scandinavian University Books. ISBN 978-91-24-27645-4.

• Gopalakrishnan, G.P. (1991). Periyar: Father of the Tamil race. Chennai: Emerald Publishers.

• Ralhan, O. P. (2002). Encyclopaedia of Political Parties. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. ISBN 81-7488-865-9.

• Saraswathi, S. (2004). Towards Self-Respect. Madras: Institute of South Indian Studies.

• Veeramani, K. (1992). Periyar on Women's Rights. Chennai: Emerald Publishers.

• Veeramani, K. (2005). Collected Works of Periyar E.V.R. Chennai: The Periyar Self-Respect Propaganda Institution.

Further reading• Bandistse, D.D., (2008). Humanist Thought in Contemporary India. B.R. Pub: New Delhi.

• Bandyopadhyaya, Sekhara, (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A history of modern India. Orient Longman: New Delhi. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2

• Biswas, S.K., (1996). Pathos of Marxism in India. Orion Books: New Delhi.

• Chand, Mool, (1992). Bahujan and their Movement. Bahujan Publication Trust: New Delhi.

• Dirks, Nicholas B., (2001). Castes of mind : colonialism and the making of modern India. Princeton University Press: Princeton, New Jersey.

• Kothandaraman, Ponnusamy, (1995). Tamil Varalarril Tantai Periyar (Tamil). Pumpolil Veliyitu: Chennai.

• Mani, Braj Ranjan, (2005). Debrahmanising History: Dominance and Resistance in Indian Society. Manohar: New Delhi.

• Mission Prakashan, (2003). Second Freedom Struggle: Chandapuri’s Call to Overthrow Brahmin Rule. Mission Prakashan Patna: Bihar.

• Omvedt, Gail, (2006). Dalit Visions. Oscar Publications: New Delhi.

• Ram, Dadasaheb Kanshi, (2001). How to Revive the Phule-Ambedkar-Periyar Movement in South India. Bahujan Samaj Publications: Bangalore.

• Ramasami, Periyar, [3rd edition] (1998). Declaration of War on Brahminism. Chennai.

• Ramasami, Periyar E.V., [ new ed] (1994). Periyana. Chintakara Chavadi: Bangalore.

• Ramasami, Periyar, [new ed] (1994). Religion and Society:: Selections from Periyar’s Speeches and Writings. Emerald Publishers: Madras.

• Richman, Paula, (1991). Many Ramayanas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press: Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-07281-2.

• Sen, Amiya P., (2003). Social and Religious Reform: The Hindus of British India. Oxford University Press: New Delhi; New York.

• Srilata, K., (2006). Other Half of the Coconut: Women Writing Self-Respect History – an anthology of self-respect literature, 1928–1936. Oscar Publications: Delhi.

• Thirumavalavan, Thol; Meena Kandasamy (2003). Talisman, Extreme Emotions of Dalit Liberation: Extreme emotions of Dalit Liberation. Popular Prakashan: Mumbai.

• Thirumavalavan, Thol; Meena Kandasamy (2004). Uproot Hindutva: The Fiery Voice of the Liberation Panthers. Popular Prakashan.

• Venugopal, P., (1990). Social Justice and Reservation. Emerald Publishers: Madras.

• Yadav, Bibhuti, (2002). Dalits in India (A set of 2 Volumes). Anmol Publications. New Delhi.

• Gawthaman.Pasu, (2009). "E.V.Ramasamy enginra naan". Bhaathi Puthakalayam. Chennai.

External links• Periyar (official website) (in English)

• Thanthai Periyar (in English)

• Periyar Kural (online radio in Tamil)

• Rationalist/Social Reformer (article) (in English)

• The Revolutionary Sayings of Periyar (in English)

• `The economic interest... that was the contradiction' (article) (in English)

• Thanthai Periyar (in English)