by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/21/20

[Caroline Rhys Davis] studied Sanskrit and Indian Philosophy with Reinhold Rost.

-- Caroline Rhys Davids, by Wikipedia

I have to thank Dr. [Reinhold] Rost, the Librarian of the India Office, at whose suggestion I undertook this work, for his kindness and courtesy in facilitating some references which I found it necessary to make to the India Office Library.

-- Buddha: His Life, His Doctrine, His Order, by Dr. Hermann Oldenberg, Professor at the University of Berlin, Editor of the Vinaya Pitakam and the Dipavamsa in Pali, Translated from the German by William Hoey, M.A., D.Lit., Member of the Royal Asiatic Society, Asiatic Society of Bengal, etc., of Her Majesty's Bengal Civil Service

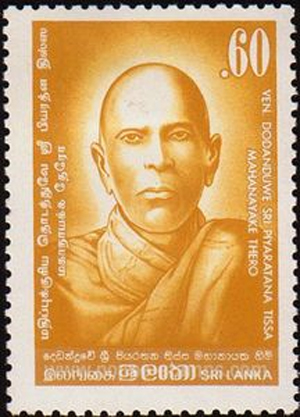

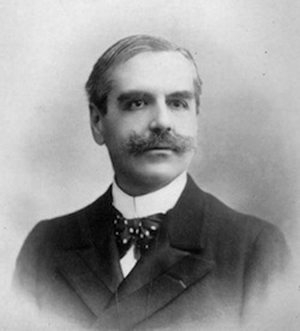

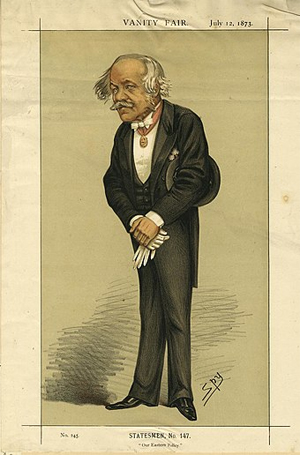

Orientalist Reinhold Rost (1822-1896), headlibrarian to the India Office Library, about 1890

Reinhold Rost (1822–1896) was a German orientalist, who worked for most of his life at St Augustine's Missionary College, Canterbury in England ...

St Augustine’s College in Canterbury, Kent, United Kingdom, was located within the precincts of St Augustine's Abbey about 0.2 miles (335 metres) ESE of Canterbury Cathedral. It served first as a missionary college of the Church of England (1848-1947) and later as the Central College of the Anglican Communion (1952-1967).

The mid-19th century witnessed a "mass-migration" from England to its colonies. In response, the Church of England sent clergy, but the demand for them to serve overseas exceeded supply. Colonial bishoprics were established, but the bishops were without clergy. The training of missionary clergy for the colonies was “notoriously difficult” because they were required to have not only “piety and desire”, they were required to have an education “equivalent to that of a university degree”. The founding of the missionary college of St Augustine’s provided a solution to this problem.

The Revd Edward Coleridge, a teacher at Eton College, envisioned establishing a college for the purpose of training clergy for service in the colonies: both as ministers for the colonists and as missionaries to the native populations...

-- St Augustine's College, Canterbury, by Wikipedia

and as head librarian at the India Office Library, London.

Life

He was the son of Christian Friedrich Rost, a Lutheran minister, and his wife Eleonore Glasewald, born at Eisenberg in Saxen-Altenburg on 2 February 1822. He was educated at the Eisenberg gymnasium school, and, after studying under Johann Gustav Stickel and Johann Gildemeister, graduated Ph.D. at the University of Jena in 1847. In the same year he came to England, to act as a teacher in German at the King's School, Canterbury. After four years, on 7 February 1851, he was appointed oriental lecturer at St. Augustine's Missionary College, Canterbury, founded to educate young men for mission work. This post he held for the rest of his life.[1]

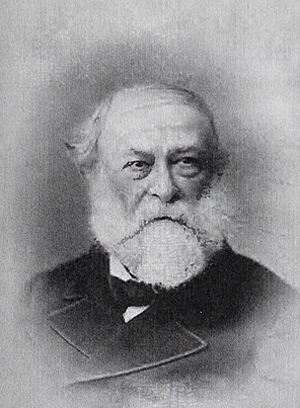

In London, Rost met Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, and was elected, in December 1863, secretary to the Royal Asiatic Society, a post he held for six years.

Sir Henry Creswicke Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, GCB FRS (5 April 1810 – 5 March 1895) was a British East India Company army officer, politician and Orientalist, sometimes described as the Father of Assyriology. His son, also Henry, was to become a senior commander in the British Army during World War I...

Rawlinson was appointed political agent at Kandahar in 1840. In that capacity he served for three years, his political labours being considered as meritorious as was his gallantry during various engagements in the course of the Afghan War; for these he was rewarded by the distinction of Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1844.

Serendipitously, he became known personally to the governor-general, which resulted in his appointment as political agent in Ottoman Arabia. Thus he settled in Baghdad, where he devoted himself to cuneiform studies. He was now able, with considerable difficulty and at no small personal risk, to make a complete transcript of the Behistun inscription, which he was also successful in deciphering and interpreting. Having collected a large amount of invaluable information on this and kindred topics, in addition to much geographical knowledge gained in the prosecution of various explorations (including visits with Sir Austen Henry Layard to the ruins of Nineveh), he returned to England on leave of absence in 1849.

He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in February 1850 on account of being "The Discoverer of the key to the Ancient Persian, Babylonian, and Assyrian Inscriptions in the Cuneiform character. The Author of various papers on the philology, antiquities, and Geography of Mesopotamia and Central Asia. Eminent as a Scholar".

Rawlinson remained at home for two years, published in 1851 his memoir on the Behistun inscription, and was promoted to the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He disposed of his valuable collection of Babylonian, Sabaean, and Sassanian antiquities to the trustees of the British Museum, who also made him a considerable grant to enable him to carry on the Assyrian and Babylonian excavations initiated by Layard. During 1851 he returned to Baghdad. The excavations were performed by his direction with valuable results, among the most important being the discovery of material that contributed greatly to the final decipherment and interpretation of the cuneiform character. Rawlinson's greatest contribution to the deciphering of the cuneiform scripts was the discovery that individual signs had multiple readings depending on their context. While at the British Museum, Rawlinson worked with the younger George Smith.

An equestrian accident in 1855 hastened his determination to return to England, and in that year he resigned his post in the East India Company. On his return to England the distinction of Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath was conferred upon him, and he was appointed a crown director of the East India Company.

The remaining forty years of his life were full of activity—political, diplomatic, and scientific—and were spent mainly in London. In 1858 he was appointed a member of the first India Council, but resigned during 1859 on being sent to Persia as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary. The latter post he held for only a year, owing to his dissatisfaction with circumstances concerning his official position there. Previously he had sat in Parliament as Member of Parliament (MP) for Reigate from February to September 1858; he was again MP for Frome, from 1865 to 1868. He was appointed to the Council of India again in 1868, and continued to serve upon it until his death. He was a strong advocate of the forward policy in Afghanistan, and counselled the retention of Kandahar.

Rawlinson was one of the most important figures arguing that Britain must check Russian ambitions in South Asia. He was a strong advocate of the forward policy in Afghanistan, and counselled the retention of Kandahar. He argued that Tsarist Russia would attack and absorb Khokand, Bokhara and Khiva (which they did – they are now parts of Uzbekistan) and warned they would invade Persia (present-day Iran) and Afghanistan as springboards to British India.

He was a trustee of the British Museum from 1876 till his death. He was created Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath in 1889, and a Baronet in 1891; was president of the Royal Geographical Society from 1874 to 1875, and of the Royal Asiatic Society from 1869 to 1871 and 1878 to 1881; and received honorary degrees at Oxford, Cambridge, and Edinburgh.

-- Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, by Wikipedia

Through Rawlinson he became on 1 July 1869 librarian at the India Office, on the retirement of FitzEdward Hall, and imposed order on its manuscripts.

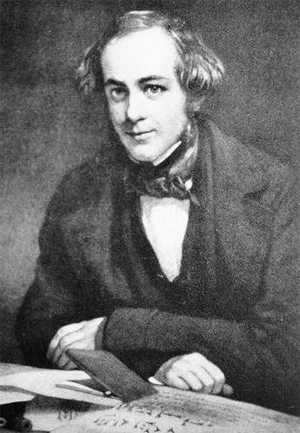

Fitzedward Hall (March 21, 1825 - February 1, 1901) was an American Orientalist, and philologist. He was the first American to edit a Sanskrit text, and was an early collaborator in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) project...

He graduated with the degree of civil engineer from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute at Troy in 1842, and entered Harvard in the class of 1846. His Harvard classmates included Charles Eliot Norton, who later visited him in India in 1849, and Francis James Child. Just before his class graduated but after completing the work for his degree he abruptly left college and took ship out of Boston to India, allegedly in search of a runaway brother. His ship foundered and was wrecked on its approach to the harbor of Calcutta, where he found himself stranded. Although it was not his intention, he was never to return to the United States. At this time, he began his study of Indian languages, and in January 1850 he was appointed tutor in the Government Sanskrit College at Benares. In 1852, he became the first American to edit a Sanskrit text, namely the Vedanta treatises Ātmabodha and Tattvabodha. In 1853, he became professor of Sanskrit and English at the Government Sanskrit College; and in 1855 was appointed to the post of Inspector of Public Instruction in Ajmere-Merwara and in 1856 in the Central Provinces.

In 1857, Hall was caught up in the Sepoy Mutiny. The Manchester Guardian later gave this account:[2] "When the Mutiny broke out he was Inspector of Public Instruction for Central India, and was beleaguered in the Saugor Fort. He had become an expert tiger shooter, and turned this proficiency to account during the siege of the fort, and afterwards as a volunteer in the struggle for the re-establishment of the British power in India."

In 1859, he published at Calcutta his discursive and informative A Contribution Towards an Index to the Bibliography of the Indian Philosophical Systems, based on the holdings of the Benares College and his own collection of Sanskrit manuscripts, as well as numerous other private collections he had examined. In the introduction, he regrets that this production was in press in Allahabad and would have been put before the public in 1857, "had it not been impressed to feed a rebel bonfire."

He settled in England and in 1862 received the appointment to the Chair of Sanskrit, Hindustani and Indian jurisprudence in King's College London, and to the librarianship of the India Office. An unsuccessful attempt was made by his friends to lure him back to Harvard by endowing a Chair of Sanskrit for him there, but this project came to nothing. His collection of a thousand Oriental manuscripts he gave to Harvard...

In 1869 Hall was dismissed by the India Office, which accused him (by his own account) of being a drunk and a foreign spy, and expelled from the Philological Society after a series of acrimonious exchanges in the letters columns of various journals.

-- Fitzedward Hall, by Wikipedia

He secured for students free admission to the library. He retired in 1893 after 24 years of service at the age of 70.[1] His successor as head librarian of the India Office Library became the Orientalist and Sanskritist Charles Henry Tawney (1837-1922).

Rost gained many distinctions and awards. He was created Hon. LL.D. of Edinburgh in 1877, and a Companion of the Indian Empire in 1888. He died at Canterbury on 7 February 1896.[1]

Works

Rost was familiar with some twenty or thirty languages in all. His own works were:[1]

• Treatise on the Indian Sources of the Ancient Burmese Laws, 1850.

• A Descriptive Catalogue of the Palm Leaf MSS. belonging to the Imperial Public Library of St. Petersburg, 1852.

• Revision of Specimens of Sanscrit MSS. published by the Paleographical Society, 1875.

Rost's India Office Library catalogue of Sanskrit works was a significant bibliographic advance.[2] He edited:[1]

• Horace Hayman Wilson, Essays on the Religions of the Hindus and on Sanscrit Literature, 5 vols. 1861–5;

• Brian Houghton Hodgson, Essays on Indian Subjects, 2 vols. 1880;

• Miscellaneous papers relating to Indo-China and the Indian Archipelago (Trübner's "Oriental Series", 4 vols. 1886–8);

• The last three volumes of Trübner's Oriental Record; and

• Trübner's series of Simplified Grammars.

He contributed notices of books to Luzac's Oriental List, articles on "Malay Language and Literature", "Pali", "Rajah", and "Thugs" to the ninth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, and published in The Athenæum and The Academy.[1]

Family

Rost married, in 1863, Minna, daughter of late Chief-justice J. F. Laue, of Magdeburg; they had seven children, two of whom died in childhood.[3] Son Ernst (Ernest) Reinhold Rost (born 1872) became Major of the Indian Medical Service (IMS), led newly founded Yangon General Hospital in Rangoon (Burma) and was active in the propagation of Buddhism in England.[4]

Biography

• Oskar Weise: Der Orientalist Dr. Reinhold Rost, sein Leben,und sein Streben. Leipzig : Teubner 1897. 71 p. (Mitteilungen des Geschichts- und Altertumsforschenden Vereins zu Eisenberg).

Notes

1. Lee, Sidney, ed. (1897). "Rost, Reinhold" . Dictionary of National Biography. 49. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

2. Katz, J. B. "Rost, Reinhold". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24144. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

3. Weise 1897, p.55

4. Weise 1897, 55

External links

Attribution

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Lee, Sidney, ed. (1897). "Rost, Reinhold". Dictionary of National Biography. 49. London: Smith, Elder & Co.