by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/26/20

Henri de Saint-Simon

Born: 17 October 1760, Paris, France

Died: 19 May 1825 (aged 64), Paris, France

Era: 19th-century philosophy

Region: Western philosophy

School: Utopian socialism; Saint-Simonianism

Main interests: Political philosophy

Notable ideas: The industrial class/idling class distinction

Influences: Francis Bacon,[1] René Descartes,[1] John Locke,[1] Isaac Newton,[1] Adam Smith,[2] Augustin Thierry, Anne Robert Jacques Turgot,[3] Emmanuel Sieyès,[3] Joseph de Maistre,[4] Charles Dunoyer, Marquis de Condorcet,[3] Jean-Baptiste Say, Nicolas-Edme Rétif[5]

Influenced: Auguste Comte, Prosper Enfantin, John Stuart Mill,[6] Pierre-Joseph Proudhon,[7] Karl Marx, Pierre Leroux, Michel Chevalier, Péreire brothers, Lorenz von Stein,[8] Thorstein Veblen[9]

Claude Henri de Rouvroy, comte de Saint-Simon, often referred to as Henri de Saint-Simon (French: [ɑ̃ʁi də sɛ̃ simɔ̃]; 17 October 1760 – 19 May 1825), was a French political and economic theorist and businessman whose thought had a substantial influence on politics, economics, sociology and the philosophy of science.

He created a political and economic ideology known as Saint-Simonianism that claimed that the needs of an industrial class, which he also referred to as the working class, needed to be recognized and fulfilled to have an effective society and an efficient economy.[10] Unlike conceptions within industrializing societies of a working class being manual labourers alone, Saint-Simon's late-18th century conception of this class included all people engaged in productive work that contributed to society, that included businesspeople, managers, scientists, bankers, along with manual labourers amongst others.[11] He said the primary threat to the needs of the industrial class was another class he referred to as the idling class, that included able people who preferred to be parasitic and benefit from the work of others while seeking to avoid doing work.[10] Saint-Simon stressed the need for recognition of the merit of the individual and the need for hierarchy of merit in society and in the economy, such as society having hierarchical merit-based organizations of managers and scientists to be the decision-makers in government.[11] He strongly criticized any expansion of government intervention into the economy beyond ensuring no hindrances to productive work and reducing idleness in society, regarding intervention beyond these as too intrusive.[10]

Saint Simon's conceptual recognition of broad socio-economic contribution, and his Enlightenment valorization of scientific knowledge, soon inspired and influenced utopian socialism,[11] liberal political theorist John Stuart Mill,[6] anarchism through its founder Pierre-Joseph Proudhon who was inspired by Saint-Simon's thought[7] and Marxism with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels identifying Saint-Simon as an inspiration to their ideas and classifying him among the utopian socialists.[11]

Utopian socialism is the first current of modern socialism and socialist thought as exemplified by the work of Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier, Étienne Cabet, Robert Owen and Henry George.[1][2] Utopian socialism is often described as the presentation of visions and outlines for imaginary or futuristic ideal societies, with positive ideals being the main reason for moving society in such a direction. Later socialists and critics of utopian socialism viewed utopian socialism as not being grounded in actual material conditions of existing society and in some cases as reactionary. These visions of ideal societies competed with Marxist-inspired revolutionary social democratic movements.

As a term or label, utopian socialism is most often applied to, or used to define, those socialists who lived in the first quarter of the 19th century who were ascribed the label utopian by later socialists as a pejorative in order to imply naiveté and to dismiss their ideas as fanciful and unrealistic. A similar school of thought that emerged in the early 20th century which makes the case for socialism on moral grounds is ethical socialism.

One key difference between utopian socialists and other socialists such as most anarchists and Marxists is that utopian socialists generally do not believe any form of class struggle or social revolution is necessary for socialism to emerge. Utopian socialists believe that people of all classes can voluntarily adopt their plan for society if it is presented convincingly. They feel their form of cooperative socialism can be established among like-minded people within the existing society and that their small communities can demonstrate the feasibility of their plan for society.

-- Utopian socialism, by Wikipedia

Saint-Simon's views also influenced 20th century sociologist and economist Thorstein Veblen, including Veblen's creation of institutional economics that has included prominent economists as adherents.[12]

Biography

Early years

Henri de Saint-Simon was born in Paris as a French aristocrat. His grandfather's cousin had been the Duke of Saint-Simon.[13] "When he was a young man, being of a restless disposition ... he went to America where he entered into American service and took part in the siege of Yorktown under General Washington."[14]

From his youth, Saint-Simon was highly ambitious. He ordered his valet to wake him every morning with, "Remember, monsieur le comte, that you have great things to do."[15] Among his early schemes was one to connect the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans by a canal, and another to construct a canal from Madrid to the sea.[16]

During the American Revolution, Saint-Simon joined the Americans, and believed that their revolution signaled the beginning of a new era.[17] He fought alongside the Marquis de Lafayette between 1779 and 1783, and was imprisoned by British forces. After his release, he returned to France to study engineering and hydraulics at the Ecole de Mézières.[18]

At the beginning of the French Revolution in 1789, Saint-Simon quickly endorsed the revolutionary ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity. In the early years of the revolution, Saint-Simon devoted himself to organizing a large industrial structure in order to found a scientific school of improvement. He needed to raise some funds to achieve his objectives, which he did by land speculation. This was only possible in the first few years of the revolution because of the growing instability of the political situation in France, which prevented him from continuing his financial activities and indeed put his life at risk. Saint-Simon and Talleyrand planned to profiteer during the Terror by buying the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, stripping its roof of metal, and selling the metal for scrap. Saint-Simon was imprisoned on suspicion of engaging in counter-revolutionary activities. He was released in 1794 at the end of the Terror.[17] After he recovered his freedom, Saint-Simon found himself immensely rich due to currency depreciation, but his fortune was subsequently stolen by his business partner. Thenceforth he decided to devote himself to political studies and research. After the establishment of the Ecole Polytechnique in 1794, a school established to train young men in the arts of sciences and industry and funded by the state, Saint-Simon became involved with the new school.[19]

Life as a working adult

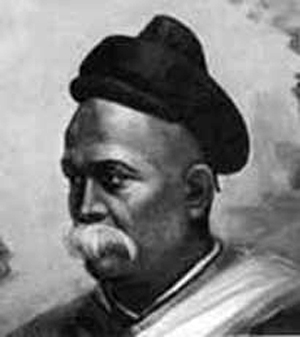

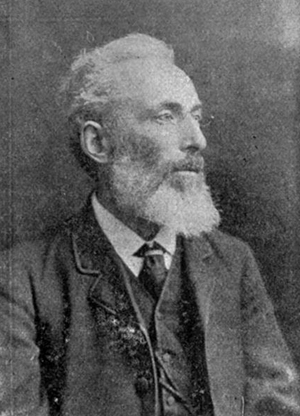

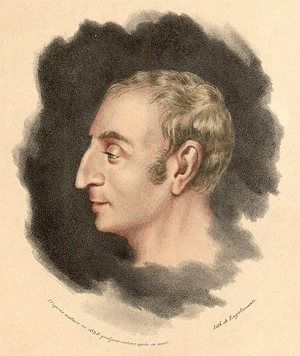

Henri de Saint-Simon, portrait from the first quarter of the 19th century

When he was nearly 40 he went through a varied course of study and experiment to enlarge and clarify his view of things. One of these experiments was an unhappy marriage in 1801 to Alexandrine-Sophie Goury de Champgrand, undertaken so that he might have a literary salon. After a year, the marriage was dissolved by mutual consent. The result of his experiments was that he found himself completely impoverished, and lived in penury for the remainder of his life. The first of his numerous writings, mostly scientific and political, was Lettres d'un habitant de Genève, which appeared in 1802. In this first work, he called for the creation of a religion of science with Isaac Newton as a saint.[19] Around 1814 he wrote the essay "On Reconstruction of the European Community" and sent it to the Congress of Vienna. He proposed a European kingdom, building on France and the United Kingdom.[20]

In 1817, in a treatise entitled L'Industrie, he began to propound his socialist views, which he developed further in L'Organisateur (1819), a periodical on which Augustin Thierry and Auguste Comte collaborated. One of Saint-Simon's major beliefs was that the world should be linked with canals.[19]

L'Industrie caused a sensation, but brought few converts. A couple of years later in his writing career, Saint-Simon found himself ruined, and was forced to work for a living. After a few attempts to recover his money from his former partner, he received financial support from Diard, a former employee, and was able to publish in 1807 his second book, Introduction aux travaux scientifiques du XIX siècle. Diard died in 1810 and Saint-Simon found himself poor again, and this time also in poor health. He was sent to a sanatorium in 1813, but with financial help from relatives he had time to recover his health and gain some intellectual recognition in Europe. In February 1821 Du système industriel appeared, and in 1823–1824 Catéchisme des industriels.[21]

Death and legacy

Saint-Simon's grave in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris

On March 9, 1823, disappointed by the lack of results of his writing (he had hoped they would guide society towards social improvement), he attempted suicide in despair.[22] Remarkably, he shot himself in the head six times without succeeding, losing his sight in one eye.[23]

Finally, very late in his career, he did link up with a few ardent disciples. The last and most important expression of his views is Nouveau Christianisme (1825), which he left unfinished.

He was buried in Le Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, France.

Ideas

Industrialism

In 1817 Saint-Simon published a manifesto called the "Declaration of Principles" in his work titled L'Industrie ("Industry").[10] The Declaration was about the principles of an ideology called industrialism that called for the creation of an industrial society led by people within what he defined as the industrial class.[10] The industrial class, also referred to as the working class, was defined as including all people engaged in productive work that contributed to society, emphasizing scientists and industrialists, but including engineers, businesspeople, managers, bankers, manual workers, and others.[11]

Saint-Simon said the primary threat to the needs of the industrial class was another class he referred to as the idling class, that included able people who preferred to be parasitic and benefit from the work of others while seeking to avoid doing work.[10] He saw the origins of this parasitic activity by idlers in what he regarded as the natural laziness of humanity.[10] He believed the principal economic roles of government were to insure that productive activity in the economy is unhindered and to reduce idleness in society.[10]

In the Declaration Saint-Simon strongly criticized any expansion of government intervention into the economy beyond these two principal economic roles, saying that when the government goes beyond these roles, it becomes a "tyrannical enemy of industry" and that the industrial economy will decline as a consequence of such excessive government intervention.[10] Saint-Simon stressed the need for recognition of the merit of the individual and the need for hierarchy of merit in society and in the economy, such as society having hierarchical merit-based organizations of managers and scientists to be the decision-makers in government.[11] His views were radical for his time. He built on Enlightenment ideas which challenged church doctrine and the older regime with the idea of progress from industry and science[19]

Heavily influenced by the absence of social privilege he saw in the early United States, Saint-Simon renounced his aristocratic title and came to favor a form of meritocracy, becoming convinced that science was the key to progress and that it would be possible to develop a society based on objective scientific principles.[24] He claimed that feudal society in France and elsewhere needed to be dissolved and transformed into an industrial society.[25] As such, he invented the conception of the industrial society.[25]

Saint-Simon's economic views and ideas were influenced by Adam Smith whom Saint-Simon deeply admired, and referred to him in praise as "the immortal Adam Smith".[2] He shared with Smith the belief that taxes needed to be much reduced from what they were then in order to have a more just industrial system.[2] Saint-Simon desired the minimization of government intervention into the economy to prevent disruption of productive work.[2] He emphasized more emphatically than Smith that state administration of the economy was generally parasitic and hostile to the needs of production.[25] Like Adam Smith, Saint-Simon's model of society emulated the scientific methods of astronomy, and said "The astronomers only accepted those facts which were verified by observation; they chose the system which linked them best, and since that time, they have never led science astray."[26]

Saint-Simon reviewed the French Revolution and regarded it as an upheaval driven by economic change and class conflict. In his analysis he believed that the solution to the problems that led to the French Revolution would be the creation of an industrial society where hierarchy of merit and respect for productive work would be the basis of society, while ranks of hereditary and military hierarchy would lessen in importance in society because they were not capable to lead a productive society.[11]

Karl Marx identified Saint-Simon as being among whom he called the "utopian socialists", though historian Alan Ryan regards certain followers of Saint-Simon, rather than Saint-Simon himself, as being responsible for the rise of utopian socialism that based itself upon Saint-Simon's ideas.[11] Ryan also distinguishes between Saint-Simon's conceptions and Marxism's, as Saint-Simon did not promote independent working-class organization and leadership as a solution to capitalist societal problems, nor did he adhere to the Marxist definition of the working class as excluded by fundamental private property law from control over the means of production.[11] Unlike Marx, Saint-Simon did not regard class relations, vis the means of production, to be an engine of socio-economic dynamics but rather the form of management.[11] Furthermore, Saint-Simon was not critical of capitalists as exclusive owners, collaborators, controllers, and decision-makers. Rather, he regarded capitalists as an important component of the "industrial class."[27] Ryan further suggests that by the 1950s it was clear that Saint-Simon had presaged the "modern" understanding of industrial society.[11]

Feudalism and aristocracy

In opposition to the feudal and military system—the former aspect of which had been strengthened by the restoration—he advocated a form of technocratic socialism, an arrangement whereby industrial chiefs should control society - similar to Plato's philosopher kings. In place of the medieval church, spiritual direction of society should fall to the men of science. Men who are fitted to organize society for productive labour are entitled to rule it. The conflict between labour and capital emphasized by later socialism is not present in Saint-Simon's work, but it is assumed that the industrial chiefs, to whom the control of production is to fall, shall rule in the interest of society. [SOURCE] Later on, the cause of the poor receives greater attention until, in his greatest work, Nouveau Christianisme (The New Christianity), it takes on the form of a religion. This development of his ideas occasioned his final quarrel with Comte.

Religious views

Prior to the publication of the Nouveau Christianisme, Saint-Simon had not concerned himself with theology. In this work he starts from a belief in God, and his object in the treatise is to reduce Christianity to its simple and essential elements. He does this by clearing it of the dogmas and other excrescences and defects that he says gathered round the Catholic and Protestant forms of it. He propounds as the comprehensive formula of the new Christianity this precept: "The whole of society ought to strive towards the amelioration of the moral and physical existence of the poorest class; society ought to organize itself in the way best adapted for attaining this end."[28] This principle became the watchword of the entire Saint-Simon school of thought.

Influence

See also: Saint-Simonianism

During his lifetime the views of Saint-Simon had very little influence; he left only a few devoted disciples who continued to advocate the doctrines of their master, whom they revered as a prophet. The most acclaimed disciple of Saint-Simon was Auguste Comte.[29] Others included Olinde Rodrigues, the favoured disciple of Saint-Simon, and Barthélemy Prosper Enfantin who together had received Saint-Simon's last instructions. Their first step was to establish a journal, Le Producteur, but it was discontinued in 1826. The sect had begun to grow, and before the end of 1828 had meetings not only in Paris but in many provincial towns.

An important departure was made in 1828 by Amand Bazard, who gave a "complete exposition of the Saint-Simonian faith" in a long course of lectures in Paris, which was well attended. His Exposition de la doctrine de St Simon (2 vols., 1828–1830), which is by far the best account of it, won more adherents. The second volume was chiefly by Enfantin, who along with Bazard stood at the head of the society, but who was superior in philosophical acumen and was prone to push his deductions to extremities. The revolution of July (1830) brought a new freedom to the socialist reformers. A proclamation was issued demanding community of goods, abolition of the right of inheritance and enfranchisement of women.

Early next year the school obtained possession of Le Globe through Pierre Leroux, who had joined the school. The school now counted among its number some of the ablest and most promising young men in France, many of the pupils of the École Polytechnique having caught its enthusiasm. The members formed themselves into an association arranged in three grades, and constituting a society or family, which lived out of a common purse in the Rue Monsigny. Before long dissensions began to arise in the sect. Bazard, a man of stolid temperament, could no longer work in harmony with Enfantin, who desired to establish an arrogant and fantastic sacerdotalism with lax notions as to marriage and the relations between the sexes. In the name of progress, Enfantin announced that the gulf between the sexes was too wide and this social inequality would impede rapid growth of society. Enfantin called for the abolition of prostitution and for the ability for women to divorce and obtain legal rights. This was considered radical for the time.[30]

After a time Bazard seceded and many of the strongest supporters of the school followed his example. A series of extravagant entertainments given by the society during the winter of 1832 reduced its financial resources and greatly discredited it in character. They moved to Ménilmontant, to a property of Enfantin, where they lived in a communalistic society, distinguished by a peculiar dress. Although the monks of Enfantin's school were required to be celibate, rumors were spread that they engaged in orgies.[31] Shortly after, the chiefs were tried and condemned for proceedings prejudicial to the social order and the sect was entirely broken up in 1832. Many of its members became famous as engineers, economists and men of business. Enfantin would go on to organize an expedition of the disciples to Constantinople, and then to Egypt, where he influenced the creation of the Suez Canal.[32]

French feminist and socialist writer Flora Tristan (1803–1844) claimed that Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, anticipated Saint-Simon's ideas by a generation.[33][dubious – discuss]

In Fyodor Dostoyevsky's novel The Possessed, 'Saint-Simonist' and 'Fourierist' are used as derogatory insults of others by many of the politically active characters.

Works

Saint-Simon wrote various accounts of his views:

• Lettres d'un habitant de Genève à ses contemporains (1803),

• L'Industrie (1816-1817),

• Le Politique (1819),

• L'Organisateur (1819-1820),

• Du système industriel, 1822

• Catéchisme des industriels (1823-1824),

• Nouveau Christianisme (1825).

• An edition of the works of Saint-Simon and Enfantin was published by the survivors of the sect (47 vols., Paris, 1865–1878).

See also

• French Revolution

• Meritocracy

• Positivism

• Scientism

• Society of the Friends of Truth

• Utopian socialism

Notes

1. Jeremy Jennings. Revolution and the Republic: A History of Political Thought in France Since the Eighteenth Century. Oxford University Press, 2011. p. 347.

2. Gregory Claeys. Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-century Thought. Oxon, UK: Routledge, 2005. p. 136.

3. Pilbeam, Pamela M. (2014). Saint-Simonians in Nineteenth-Century France: From Free Love to Algeria. Springer. p. 5.

4. John Powell, Derek W. Blakeley, Tessa Powell. Biographical Dictionary of Literary Influences: The Nineteenth Century, 1800-1914. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001. p. 267.

5. Jean-René Suratteau, "Restif (de la Bretonne) Nicolas Edme", in: Albert Soboul (ed.), Dictionnaire historique de la Révolution française, Paris, PUF, 1989, 2nd ed. Quadrige, 2005, pp. 897–898.

6. Nicholas Capaldi. John Stuart Mill: A Biography. Cambridge University Press, 2004. pp. 77–80.

7. Rob Knowles. Political Economy from Below: Economic Thought in Communitarian Anarchism 1840-1914: Economic Thought in Communitarian Anarchism, 1840-1914. Routledge, 2013. p. 342.

8. Koslowski, Stefan (2017). "Lorenz von Stein as a disciple of Saint-Simon and the French Utopians". Revista europea de historia de las ideas políticas y de las instituciones públicas. 11.

9. Horowitz, Irving Louis, Veblen's Century: A Collective Portrait (2002), p. 142

10. Keith Taylor (ed, tr.). Henri de Saint Simon, 1760-1825: Selected writings on science, industry and social organization. New York, USA: Holmes and Meier Publishers, Inc, 1975. pp. 158–161.

11. Alan Ryan. On Politics. Book II. 2012. pp. 647–651.

12. Vincent Mosco. The Political Economy of Communication. SAGE, 2009. p. 53.

13. "Britannica".

14. Isaiah Berlin, Freedom and Its Betrayal, Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 109

15. Busky, Donald F.: "Communism in History and Theory: From Utopian Socialism to the Fall of the Soviet Union"

16. Manuel, Frank E.: "The Prophets of Paris", Harper & Row 1962

17. Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 25. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

18. Hasan, Samiul; Crocker, Ruth; Rousseliere, Damien; Dumont, Georgette; Hale, Sharilyn; Srinivas, Hari; Hamilton, Mark; Kumar, Sunil; Maclean, Charles (2010), "Saint-Simon, Claude-Henri de Rouvroy (Comte de)", in Anheier, Helmut K.; Toepler, Stefan (eds.), International Encyclopedia of Civil Society, Springer US, pp. 1341–1342, doi:10.1007/978-0-387-93996-4_811, ISBN 9780387939940

19. Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 26. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

20. Dosenrode, Søren (1998). Danske EUropavisioner. Århus: Systime. p. 11. ISBN 87-7783-959-5.

21. Saint-Simon, Henri (2012-11-14). Œuvres complètes de Saint-Simon: 4 volumes (in French). Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-062090-7.

22. Pickering, Mary (2006-04-20). Auguste Comte: Volume 1: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-521-02574-4.

23. Trombley, Stephen (2012-11-01). Fifty Thinkers Who Shaped the Modern World. Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-78239-038-1.

24. Newman, Michael. (2005) Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280431-6

25. Murray E. G. Smith. Early Modern Social Theory: Selected Interpretive Readings. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press, Inc, 1998. p. 80.

26. Murray E. G. Smith. Early Modern Social Theory: Selected Interpretive Readings. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars Press, Inc, 1998. pp. 80–81.

27. Arthur Bernie. An Economic History of Europe 1760-1930. Routledge, 1930 (original), 2010. p. 113.

28. Saint-Simon (1825). Nouveau christianisme (New Christianity). Paris, France.

29. Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 27. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

30. Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 29. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

31. Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 30. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

32. * Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 28, 31–37. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

33. Promenades dans Londres, first published 1840. Page 276, Broché edition (2003) from La Découverte.

References

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Kirkup, Thomas; Shotwell, James (1911). "Saint-Simon, Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–47.

External links

• Saint-Simon and Saint-Simonism Catholic Encyclopedia article

• Saint-Simon and Saint-Simonism: A Chapter in the History of Socialism in France by Arthur John Booth

• 'Henri de Saint-Simon: The Great Synthesist by Caspar Hewett

• New Christianity, 1825, Henri de Saint-Simon