Part 1 of 2

Allan Octavian Hume [H. X.] [Aletheia]by Wikipedia

Accessed: 8/27/20

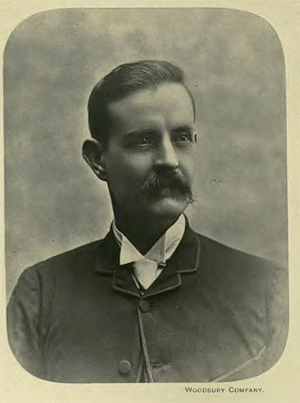

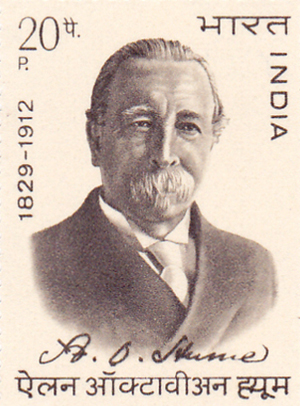

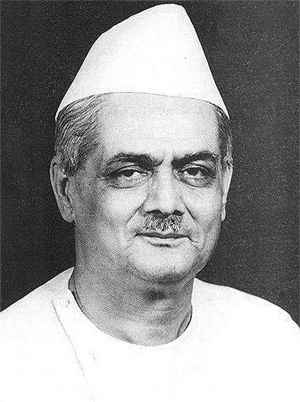

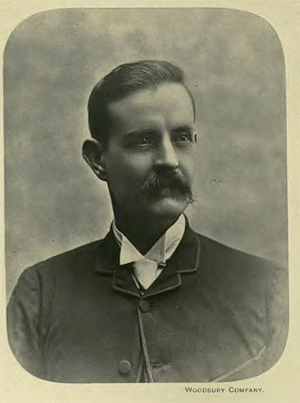

Allan Octavian Hume

Allan Octavian Hume (1829–1912) (scanned from a Woodburytype)

Born: 4 June 1829, St Mary Cray, Kent

Died: 31 July 1912 (aged 83), London, England

Nationality: British

Alma mater: University College Hospital;

East India Company CollegeOccupation: Political reformer ornithologist biologist administrator

Known for: Founder of Indian National Congress; Father of Indian Ornithology

Spouse(s): Mary Anne Grindall (m. 1853)

Children Maria Jane "Minnie" Burnley

Parent(s): Joseph Hume (father); Maria Burnley (mother)

Allan Octavian Hume, CB ICS (4 June 1829[1] – 31 July 1912[2]) was a British member of the Imperial Civil Service (later the Indian Civil Service), a political reformer, ornithologist and botanist who worked in British India. He was one of the founders of the Indian National Congress. A notable ornithologist, Hume has been called "the Father of Indian Ornithology" and, by those who found him dogmatic, "the Pope of Indian ornithology".[3]

As an administrator of Etawah, he saw the Indian Rebellion of 1857 as a result of misgovernance and made great efforts to improve the lives of the common people. The district of Etawah was among the first to be returned to normality and over the next few years Hume's reforms led to the district being considered a model of development. Hume rose in the ranks of the Indian Civil Service but like his father Joseph Hume, the radical MP, he was bold and outspoken in questioning British policies in India. He rose in 1871 to the position of secretary to the Department of Revenue, Agriculture, and Commerce under Lord Mayo. His criticism of Lord Lytton however led to his removal from the Secretariat in 1879.

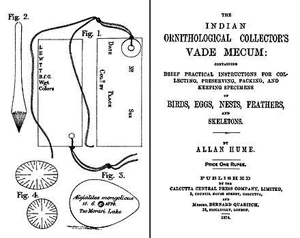

He founded the journal Stray Feathers in which he and his subscribers recorded notes on birds from across India. He built up a vast collection of bird specimens at his home in Shimla by making collection expeditions and obtaining specimens through his network of correspondents.

Following the loss of manuscripts that he had long been maintaining in the hope of producing a magnum opus on the birds of India, he abandoned ornithology and gifted his collection to the Natural History Museum in London, where it continues to be the single largest collection of Indian bird skins. He was briefly a follower of the theosophical movement founded by Madame Blavatsky. He left India in 1894 to live in London from where he continued to take an interest in the Indian National Congress, apart from taking an interest in botany and founding the South London Botanical Institute towards the end of his life.

Life and career

Early lifeHume was born at St Mary Cray, Kent,[4] a younger son (and the eighth child in a family of nine)[5] of Joseph Hume, the Radical member of parliament, by his marriage to Maria Burnley.[2]

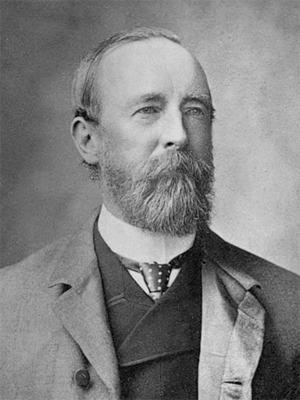

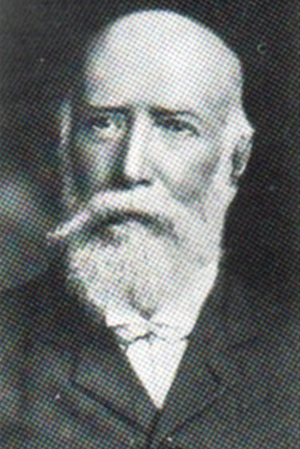

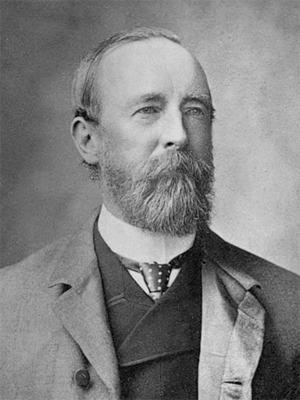

Joseph Hume FRS (22 January 1777 – 20 February 1855) was a Scottish surgeon and Radical MP...

He studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and moved to India in 1797. There, he was commissioned as a surgeon to an Army regiment, and was able to take up work as an interpreter and commissary-general due to his knowledge of Indian languages.

His knowledge of chemistry helped him provide the administration with a method to recover damp gunpowder in 1802, on the eve of Lord Lake's Maratha war. In 1808, he resigned and returned home with a fortune of about £40,000.Between 1808 and 1811, he travelled around England and Europe and, in 1812, published a blank verse translation of The Inferno.

In 1818 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society by virtue of being, according to his nomination citation, "well versed in various branches of Useful knowledge and particularly in Chimistry, in various branches of oriental literature and Antiquities".[2]

Political careerIn 1812, he purchased a seat in Parliament for Weymouth, Dorset, England, and voted as a Tory. When the parliament was dissolved the patron refused to return his money, and Hume brought an action to recover part of it. Six years later, Hume again entered the House, and made acquaintance with James Mill and the philosophical reformers of the school of Jeremy Bentham. He joined with Francis Place, of Westminster, and other philanthropists, to help improve the condition of the working classes, labouring especially to establish schools for them on the Lancastrian system, and forming savings banks.

In 1818, soon after getting married, he was returned to Parliament as member for the Aberdeen Burghs, Borders, Scotland. He was afterwards successively elected for Middlesex, England (1830), Kilkenny, Ireland (1837) and for the Montrose Burghs, Montrose, Scotland (1842), in the service of which constituency he died.

Political campaignsFrom the date of his re-entering Parliament, Hume became the self-appointed guardian of the public purse, by challenging and bringing to a direct vote every single item of public expenditure. In 1820, he secured the appointment of a committee to report on the expense of collecting tax revenue. He was very active and became known as someone who gave Chancellors of the Exchequer no peace. He exercised a check on extravagance, and helped to abolish the sinking fund. It was he who caused the word "retrenchment" to be added to the Radical programme "peace and reform." He carried on a successful warfare against the old anti-trade union combination laws that hampered workmen and favoured masters. He brought about the repeal of the laws prohibiting the export of machinery, and of the act preventing workmen from going abroad. He constantly protested against flogging in the army, the impressment of sailors and imprisonment for debt...

Personal lifeHume married Maria Burnley, the daughter of an East India Company director, and had nine children, the eighth of which was Allan Octavian Hume, the notable ornithologist and founder of the Indian National Congress.-- Joseph Hume, by Wikipedia

Until the age of eleven he was privately tutored growing up at the town house at 6 Bryanston Square in London and at their country estate, Burnley Hall in Norfolk.[1] He was educated at University College Hospital,[6] where he studied medicine and surgery and was then nominated to the Indian Civil Services which led him to study at the East India Company College, Haileybury. Early influences included his friend John Stuart Mill and Herbert Spencer.[2] He briefly served as a junior midshipman aboard a navy vessel in the Mediterranean in 1842.[1]

Etawah (1849–1867)Hume sailed to India in 1849 and the following year, joined the Bengal Civil Service at Etawah in the North-Western Provinces, in what is now Uttar Pradesh. His career in India included service as a district officer from 1849 to 1867, head of a central department from 1867 to 1870, and secretary to the Government from 1870 to 1879.[7] He married Mary Anne Grindall (26 May 1824, Meerut – March 1890, Simla) in 1853.[8]

It was only nine years after his entry to India that Hume faced the Indian Rebellion of 1857 during which time he was involved in several military actions[9][10] for which he was created a Companion of the Bath in 1860. Initially it appeared that he was safe in Etawah, not far from Meerut where the rebellion began but this changed and Hume had to take refuge in Agra fort for six months.[11] Nonetheless, all but one Indian official remained loyal and Hume resumed his position in Etawah in January 1858. He built up an irregular force of 650 loyal Indian troops and took part in engagements with them. Hume blamed British ineptitude for the uprising and pursued a policy of "mercy and forbearance".[2] Only seven persons were executed at the gallows on his orders.[12] The district of Etawah was restored to peace and order in a year, something that was not possible in most other parts.[13]

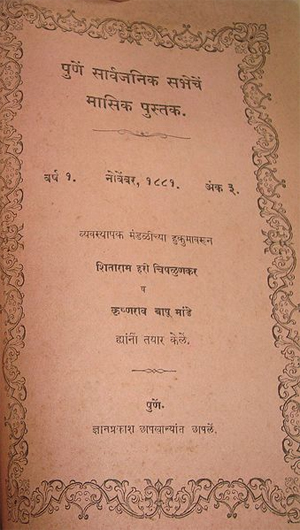

Shortly after 1857, he set about in a range of reforms. As a District Officer in the Indian Civil Service, he began introducing free primary education and held public meetings for their support. He made changes in the functioning of the police department and the separation of the judicial role. Noting that there was very little reading material with educational content, he started, along with Koour Lutchman Singh, a Hindi language periodical, Lokmitra (The People's Friend) in 1859. Originally meant only for Etawah, its fame spread.[14] Hume also organized and managed an Urdu journal Muhib-i-riaya.[15]

The system of departmental examinations introduced soon after (Hume joined the civil services) enabled Hume so to outdistance his seniors that when the rebellion broke out he was officiating Collector of Etawah, which lies between Agra and Cawnpur. Rebel troops were constantly passing through the district, and for a time it was necessary to abandon headquarters ; but both before and after the removal of the women and children to Agra, Hume acted with vigour and judgment. The steadfast loyalty of many native officials and landowners, and the people generally, was largely due to his influence, and enabled him to raise a local brigade of horse. In a daring attack on a body of rebels at Jaswantnagar he carried away the wounded joint magistrate, Mr. Clearmont Daniel,[16] under a heavy fire, and many months later he engaged in a desperate action against Firoz Shah and his Oudh freebooters at Hurchandpur. Company rule had come to an end before the ravines of the Jumna and the Chambul in the district had been cleared of fugitive rebels. Hume richly merited the C.B. (Civil division) awarded him in 1860. He remained in charge of the district for ten years or so and did good work.

— Obituary The Times of August 1st, 1912

He took up the cause of education and founded scholarships for higher education. He wrote, in 1859, that education played a key role in avoiding revolts like the one in 1857:

... assert its supremacy as it may at the bayonet's point, a free and civilized government must look for its stability and permanence to the enlightenment of the people and their moral and intellectual capacity to appreciate its blessings.[8]

In 1863 he moved for separate schools for juvenile delinquents rather than flogging and imprisonment which he saw as producing hardened criminals. His efforts led to a juvenile reformatory not far from Etawah. He also started free schools in Etawah and by 1857 he established 181 schools with 5186 students including two girls.[17] The high school that he helped build with his own money is still in operation, now as a junior college, and it was said to have a floor plan resembling the letter "H". This, according to some was an indication of Hume's imperial ego.[18] Hume found the idea of earning revenue earned through liquor traffic repulsive and described it as "The wages of sin". With his progressive ideas on social reform, he advocated women's education, was against infanticide and enforced widowhood. Hume laid out in Etawah, a neatly gridded commercial district that is now known as Humeganj but often pronounced Homeganj.[8]

Commissioner of Customs (1867–1870)In 1867 Hume became Commissioner of Customs for the North West Province, and in 1870 he became attached to the central government as Director-General of Agriculture. In 1879 he returned to provincial government at Allahabad.[8][13]

Hume's appointment, in 1867, to be Commissioner of Customs in Upper India gave him charge of the huge physical barrier[19] which stretched across the country for 2,500 miles from Attock, on the Indus, to the confines of the Madras Presidency. He carried out the first negotiations with Rajputana Chiefs, leading to the abolition of this barrier, and Lord Mayo rewarded him with the Secretaryship to Government in the Home, and afterwards, from 1871, in the Revenue and Agricultural Departments.[20]

Secretary to the Department of Revenue, Agriculture and Commerce (1871–1879)Hume was very interested in the development of agriculture. He believed that there was too much focus on obtaining revenue and no effort had been spent on improving the efficiency of agriculture. He found an ally in Lord Mayo who supported the idea of developing a complete department of agriculture. Hume noted in his Agricultural reform in India that Lord Mayo had been the only Viceroy who had any experience of working in the fields.

Hume made a number of suggestions for the improvement of agriculture placing carefully gathered evidence for his ideas. He noted the poor yields of wheat, comparing them with estimates from the records of Emperor Akbar and yields of farms in Norfolk. Lord Mayo supported his ideas but was unable to establish a dedicated agricultural bureau as the scheme did not find support from the Secretary of State for India, but they negotiated the setting up of a Department of Revenue, Agriculture and Commerce despite Hume's insistence that Agriculture be the first and foremost aim. Hume was made a secretary of this department in July 1871 leading to his move to Shimla.[8]

With the murder of Lord Mayo in the Andamans in 1872, Hume lost patronage and support for his work. He however went about reforming the department of agriculture, streamlining the collection of meteorological data (the meteorological department was set up by order number 56 on 27 September 1875 signed by Hume[21]) and statistics on cultivation and yield.[22]

Hume proposed the idea of having experimental farms to demonstrate best practices to be set up in every district. He proposed to develop fuelwood plantations "in every village in the drier portions of the country" and thereby provide a substitute heating and cooking fuel so that manure (dried cattle dung was used as fuel by the poor) could be returned to the land. Such plantations, he wrote, were "a thing that is entirely in accord with the traditions of the country – a thing that the people would understand, appreciate, and, with a little judicious pressure, cooperate in." He wanted model farms to be established in every district. He noted that rural indebtedness was caused mainly by the use of land as security, a practice that had been introduced by the British. Hume denounced it as another of "the cruel blunders into which our narrow-minded, though wholly benevolent, desire to reproduce England in India has led us." Hume also wanted government-run banks, at least until cooperative banks could be established.[8][23]

The department also supported the publication of several manuals on aspects of cultivation, a list of which Hume included as an appendix to his Agricultural Reform in India. Hume supported the introduction of cinchona and the project managed by George King to produce quinine locally at low cost.[24]

Hume was very outspoken and never feared to criticise when he thought the Government was in the wrong. Even in 1861, he objected to the concentration of police and judicial functions in the hands of police superintendents. In March 1861, he took a medical leave due to a breakdown from overwork and departed for Britain. Before leaving, he condemned the flogging and punitive measures initiated by the provincial government as 'barbarous ... torture'. He was allowed to return to Etawah only after apologising for the tone of his criticism.[2] He criticised the administration of Lord Lytton before 1879 which according to him, had cared little for the welfare and aspiration of the people of India.

Lord Lytton's foreign policy according to Hume had led to the waste of "millions and millions of Indian money".[8] Hume was critical of the land revenue policy and suggested that it was the cause of poverty in India. His superiors were irritated and attempted to restrict his powers and this led him to publish a book on Agricultural Reform in India in 1879.[2][25]

Hume noted that the free and honest expression was not only permitted but encouraged under Lord Mayo and that this freedom was curtailed under Lord Northbrook who succeeded Lord Mayo. When Lord Lytton succeeded Lord Northbrook, the situation worsened for Hume.[26] In 1879 Hume went against the authorities.[7] The Government of Lord Lytton dismissed him from his position in the Secretariat. No clear reason was given except that it "was based entirely on the consideration of what was most desirable in the interests of the public service". The press declared that his main wrongdoing was that he was too honest and too independent. The Pioneer wrote that it was "the grossest jobbery ever perpetrated" ; the Indian Daily News wrote that it was a "great wrong" while The Statesman said that "undoubtedly he has been treated shamefully and cruelly." The Englishman in an article dated 27 June 1879, commenting on the event stated, "There is no security or safety now for officers in Government employment."[27] Demoted, he left Simla and returned to the North-West Provinces in October 1879, as a member of the Board of Revenue.[28] It has pointed out that he was victimised as he was out of step with the policies of the Government, often intruding into aspects of administration with critical opinions.[28]

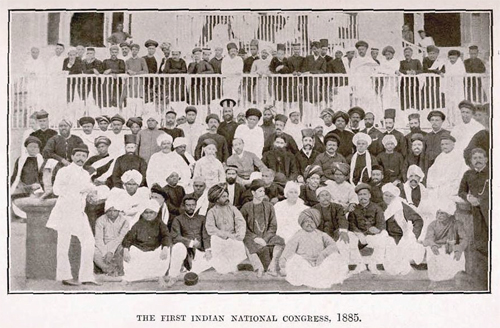

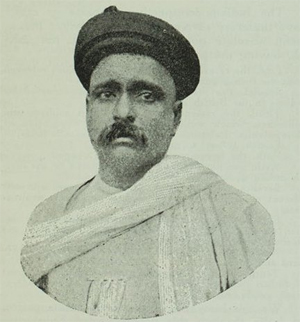

Demotion and resignation (1879–1882)In spite of the humiliation of demotion, he did not resign immediately from service and it has been suggested that this was because he needed his salary to support the publication of The Game Birds of India that he was working on.[28] Hume retired from the civil service only in 1882. In 1883 he wrote an open letter to the graduates of Calcutta University, calling upon them to form their own national political movement. This led in 1885 to the first session of the Indian National Congress held in Bombay.[29] In 1887 writing to the Public Commission of India he made what was then a statement unexpected from a civil servant — I look upon myself as a Native of India.[28]

Return to England 1894 Hume's grave in Brookwood Cemetery

Hume's grave in Brookwood CemeteryHume's wife Mary died on 30 March 1890 and news of her death reached him just as he reached London on 1 April 1890.[30] Their only daughter Maria Jane Burnley ("Minnie") (1854–1927) had married Ross Scott at Shimla on 28 December 1881.[31] Maria became a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, another occult movement, after moving to England.[32] Ross Scott was the founding secretary of the Simla Eclectic Theosophical Society, who was sometime Judicial Commissioner of Oudh and died in 1908.[33] Hume's grandson Allan Hume Scott served with the Royal Engineers in India.

Hume left India in 1894 and settled at The Chalet, 4 Kingswood Road, Upper Norwood in south London. He died at the age of eighty-three on 31 July 1912. His ashes were buried in Brookwood Cemetery.[5] The bazaar in Etawah was closed on hearing of his death and the Collector, H. R. Neville, presided over a memorial meeting.[34]

The Indian postal department issued a commemorative stamp with his portrait in 1973 and a special cover depicting Rothney Castle, his home in Shimla, was released in 2013.

Contribution to ornithology and natural historyFrom early days, Hume had a special interest in science. Science, he wrote:

...teaches men to take an interest in things outside and beyond… The gratification of the animal instinct and the sordid and selfish cares of worldly advancement; it teaches a love of truth for its own sake and leads to a purely disinterested exercise of intellectual faculties

and of natural history he wrote in 1867:[8]

... alike to young and old, the study of Natural History in all its branches offers, next to religion, the most powerful safeguard against those worldly temptations to which all ages are exposed. There is no department of natural science the faithful study of which does not leave us with juster and loftier views of the greatness, goodness, and wisdom of the Creator, that does not leave us less selfish and less worldly, less spiritually choked up with those devil's thorns, the love of dissipation, wealth, power, and place, that does not, in a word, leave us wiser, better and more useful to our fellow-men.

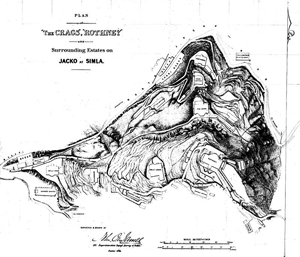

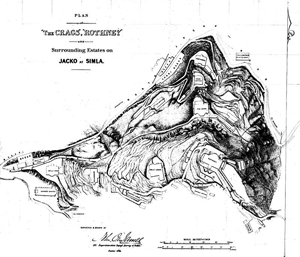

Map of the Crags and Rothney Castle, Shimla (1872)

Map of the Crags and Rothney Castle, Shimla (1872)During his career in Etawah, he built up a personal collection of bird specimens, however the first collection that he made was destroyed during the 1857 rebellion. After 1857 Hume made several expeditions to collect birds both on health leave and where work took him but his most systematic work began after he moved to Shimla. He was Collector and Magistrate of Etawah from 1856 to 1867 during which time he studied the birds of that area. He later became Commissioner of Inland Customs which made him responsible for the control of 2,500 miles (4,000 km) of coast from near Peshawar in the northwest to Cuttack on the Bay of Bengal. He travelled on horseback and camel in areas of Rajasthan to negotiate treaties with various local maharajas to control the export of salt and during these travels he took note of the birdlife:

The nests are placed indifferently on all kinds of trees (I have notes of finding them on mango, plum, orange, tamarind, toon, etc.), never at any great elevation from the ground, and usually in small trees, be the kind chosen what it may. Sometimes a high hedgerow, such as our great Customs hedge, is chosen, and occasionally a solitary caper or stunted acacia-bush.

— On the nesting of the Bay-backed Shrike (Lanius vittatus) in The Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds.

Hume appears to have planned a comprehensive work on the birds of India around 1870 and a "forthcoming comprehensive work" finds mention in the second edition of The Cyclopaedia of India (1871) by his cousin Edward Balfour.[35] His systematic plan to survey and document the birds of the Indian Subcontinent began in earnest after he started accumulating the largest collection of Asiatic birds in his personal museum and library at home in Rothney Castle on Jakko Hill, Simla. Rothney Castle, originally Rothney House was built by Colonel Octavius Edward Rothney and later belonged to P. Mitchell, C.I.E from whom Hume bought it and converted it into a palatial house with some hope that it might be bought by the Government as a Viceregal residence since the Governor-General then occupied Peterhoff, a building too small for large parties. Hume spent over two hundred thousand pounds on the grounds and buildings. He added enormous reception rooms suitable for large dinner parties and balls, as well as a magnificent conservatory and spacious hall with walls displaying his superb collection of Indian horns. He used a large room for his bird museum. He hired a European gardener, and made the grounds and conservatory a perpetual horticultural exhibition, to which he courteously admitted all visitors. Rothney Castle could only be reached by a steep road, and was never purchased by the British Government.[8][36]

Hume made several expeditions almost solely to study ornithology the largest being an expedition to the Indus area in late November 1871 and continued until the end of February 1872. In March 1873, he visited the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in the Bay of Bengal along with geologists Dr. Ferdinand Stoliczka and Dr. Dougall of the Geological Survey of India and James Wood-Mason of the Indian Museum in Calcutta. In 1875, he made an expedition to the Laccadive Islands aboard the marine survey vessel IGS Clyde under the command of Staff-Commander Ellis. The official purpose of the visit being to examine proposed sites for lighthouses. During this expedition Hume collected many bird specimens, apart from conducting a bathymetric survey to determine whether the island chain was separated from India by a deep canyon.[37][38] And in 1881 he made his last ornithological expedition to Manipur, a visit in which he collected and described the Manipur bush quail (Perdicula manipurensis), a bird that has remained obscure with few reliable reports since. Hume spent an extra day with his assistants cutting down a large tract of grass so that he could obtain specimens of this species.[39] This expedition was made on special leave following his demotion from the Central Government to a junior position on the Board of Revenue of the North Western Provinces.[8] Apart from personal travel, he also sent out a trained bird-skinner to accompany officers travelling in areas of ornithological interest such as Afghanistan.[40] Around 1878 he was spending about ₤ 1500 a year on his ornithological surveys.[28]

Hume was a member of the Asiatic Society of Bengal from January 1870 to 1891[41][42] and admitted Fellow of the Linnean Society on 3 November 1904.[43] After returning to England in 1890 he also became president of the Dulwich Liberal and Radical Association.[44]

Collection Rothney Castle, conservatory and facade (2016).

Rothney Castle, conservatory and facade (2016).Hume used his vast bird collection to good use as editor of his journal Stray Feathers. He also intended to produce a comprehensive publication on the birds of India. Hume employed William Ruxton Davison, who was brought to notice by Dr. George King, as a curator for his personal bird collection. Hume trained Davison and sent him out annually on collection trips to various parts of India as he himself was held up with official responsibilities.[8] In 1883 Hume returned from a trip to find that many pages of the manuscripts that he had maintained over the years had been stolen and sold off as waste paper by a servant. Hume was completely devastated and he began to lose interest in ornithology due to this theft and a landslip, caused by heavy rains in Simla, which had damaged his museum and many of the specimens. He wrote to the British Museum wishing to donate his collection on certain conditions. One of the conditions was that the collection was to be examined by Dr. R. Bowdler Sharpe and personally packed by him, apart from raising Dr. Sharpe's rank and salary due to the additional burden on his work caused by his collection. The British Museum was unable to heed his many conditions. It was only in 1885 after the destruction of nearly 20000 specimens, that alarm bells were raised by Dr. Sharpe and the museum authorities let him visit India to supervise the transfer of the specimens to the British Museum.[8]

Sharpe wrote of Hume's impressive private ornithological museum:[8][45]

I arrived at Rothney Castle about 10 am on the 19th of May, and was warmly welcomed by Mr Hume, who lives in a most picturesque situation high up on Jakko…From my bedroom window, I had a fine view of the snowy range. Although somewhat tired by my jolt in the Tonga from Solun, I gladly accompanied Mr. Hume at once into the museum…I had heard so much from my friends, who knew the collection intimately,…that I was not so much surprised when at last I stood in the celebrated museum and gazed at the dozens upon dozens of tin cases which filled the room. Before the landslip occurred, which carried away one end of the museum, It must have been an admirably arranged building, quite three times as large as our meeting-room at the Zoological Society, and…much more lofty. Throughout this large room went three rows of table cases with glass tops, in which were arranged a series of the birds of India sufficient for the identification of each species, while underneath these table- cases where enormous cabinets made of tin, with trays inside, containing species of birds in the table cases above. All of the rooms were racks reaching up to the ceiling, and containing immense cases full of birds… On the western side of the museum was the library, reached by a descent of three steps, a cheerful room, furnished with large tables, and containing besides the egg-cabinets, a well-chosen set of working-volumes. One ceases to wonder at the amount of work its owner got through when the excellent plan of his museum is considered. In a few minutes an immense series of specimens could be spread out on the tables, while all the books were at hand for immediate reference…After explaining to me the contents of the museum, we went below into the basement, which consisted of eight great rooms, six of them full, from floor to ceiling, of cases of birds, while at the back of the house two large verandahs were piled high with cases full of large birds, such as Pelicans, Cranes, Vultures, &c. An inspection of a great cabinet containing a further series of about 5000 eggs completed our survey. Mr. Hume gave me the keys of the museum, and I was free to commence my task at once.

Sharpe also noted:[8][45]

Mr. Hume was a naturalist of no ordinary calibre, and this great collection will remain a monument of his genius and energy of its founder long after he who formed it has passed away...Such a private collection as Mr. Hume's is not likely to be formed again; for it is doubtful if such a combination of genius for organisation with energy for the completion of so great a scheme, and the scientific knowledge requisite for its proper development will again be combined in a single individual.

The Hume collection of birds was packed into 47 cases made of deodar wood constructed on site without nails that could potentially damage specimens and each case weighing about half a ton was transported down the hill to a bullock cart to Kalka and finally the port in Bombay. The material that went to the British Museum in 1885 consisted of 82,000 specimens of which 75,577 were finally placed in the museum. A breakup of that collection is as follows (old names retained).[8] Hume had destroyed 20,000 specimens prior to this as they had been damaged by dermestid beetles.[45]

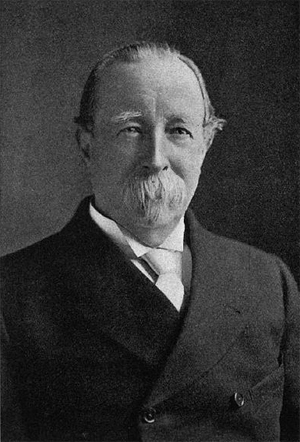

Portrait of A.O. Hume, C.B.

Portrait of A.O. Hume, C.B.• 2830 birds of prey (Accipitriformes)... 8 types

• 1155 owls (Strigiformes)...9 types

• 2819 crows, jays, orioles etc....5 types

• 4493 cuckoo-shrikes and flycatchers... 21 types

• 4670 thrushes and warblers...28 types

• 3100 bulbuls and wrens, dippers, etc....16 types

• 7304 timaliine birds...30 types

• 2119 tits and shrikes...9 types

• 1789 sun-birds (Nectarinidae) and white-eyes (Zosteropidae)...8 types

• 3724 swallows (Hirundiniidae), wagtails and pipits (Motacillidae)...8 types

• 2375 finches (Fringillidae)...8 types

• 3766 starlings (Sturnidae), weaver-birds (Ploceidae), and larks (Alaudidae)...22 types

• 807 ant-thrushes (Pittidae), broadbills (Eurylaimidae)...4 types

• 1110 hoopoes (Upupae), swifts (Cypseli), nightjars (Caprimulgidae) and frogmouths (Podargidae)...8 types

• 2277 Picidae, hornbills (Bucerotes), bee-eaters (Meropes), kingfishers (Halcyones), rollers(Coracidae), trogons (trogones)...11 types

• 2339 woodpeckers (Pici)...3 types

• 2417 honey-guides (Indicatores), barbets (Capiformes), and cuckoos (Coccyges)...8 types

• 813 parrots (Psittaciformes)...3 types

• 1615 pigeons (Columbiformes)...5 types

• 2120 sand-grouse (Pterocletes), game-birds and megapodes(Galliformes)...8 types

• 882 rails (Ralliformes), cranes (Gruiformes), bustards (Otides)...6 types

• 1089 ibises (Ibididae), herons (Ardeidae), pelicans and cormorants (Steganopodes), grebes (Podicipediformes)...7 types

• 761 geese and ducks (Anseriformes)...2 types

• 15965 eggs

Hadromys humei

Hadromys humeiThe Hume Collection contained 258 type specimens. In addition there were nearly 400 mammal specimens including new species such as Hadromys humei.[46]

The egg collection was made up of carefully authenticated contributions from knowledgeable contacts and on the authenticity and importance of the collection, E. W. Oates wrote in the 1901 Catalogue of the Collection of Birds' Eggs in the British Museum (Volume 1):

The Hume Collection consists almost entirely of the eggs of Indian birds. Mr. Hume seldom or never purchased a specimen, and the large collection brought together by him in the course of many years was the result of the willing co-operation of numerous friends resident in India and Burma. Every specimen in the collection may be said to have been properly authenticated by a competent naturalist; and the history of most of the clutches has been carefully recorded in Mr. Hume's 'Nests and Eggs of Indian Birds', of which two editions have been published.

Hume and his collector Davison took an interest in plants as well. Specimens were collected even on the first expedition to the Lakshadweep in 1875 were studied by George King and later by David Prain. Hume's herbarium specimens were donated to the collection of the Botanical Survey of India at Calcutta.[47]

Taxa describedHume described many species, some of which are now considered as subspecies. A single genus name that he erected survives in use while others such as Heteroglaux Hume, 1873 have sunk into synonymy since.[8][48][1] In his concept of species, Hume was an essentialist and held the idea that small but constant differences defined species. He appreciated the ideas of speciation and how it contradicted divine creation but preferred to maintain a position that did not reject a Creator.[49][50]

Genera• Ocyceros Hume, 1873

Species• Anas albogularis (Hume, 1873)

• Perdicula manipurensis Hume, 1881

• Arborophila mandellii Hume, 1874

• Syrmaticus humiae (Hume, 1881)

• Puffinus persicus Hume, 1872

• Ardea insignis Hume, 1878

• Pseudibis davisoni (Hume, 1875)

• Gyps himalayensis Hume, 1869

• Spilornis minimus Hume, 1873

• Buteo burmanicus Hume, 1875

• Sternula saundersi (Hume, 1877)

• Columba palumboides (Hume, 1873)

• Phodilus assimilis Hume, 1877

• Otus balli (Hume, 1873)

• Otus brucei (Hume, 1872)

• Strix butleri (Hume, 1878)

• Heteroglaux blewitti Hume, 1873

• Ninox obscura Hume, 1872

• Tyto deroepstorffi (Hume, 1875)

• Caprimulgus andamanicus Hume, 1873

• Aerodramus maximus (Hume, 1878)

• Psittacula finschii (Hume, 1874)

• Hydrornis oatesi Hume, 1873

• Hydrornis gurneyi (Hume, 1875)

• Rhyticeros narcondami Hume, 1873

• Megalaima incognita Hume, 1874

• Podoces hendersoni Hume, 1871

• Podoces biddulphi Hume, 1874

• Pseudopodoces humilis (Hume, 1871)

• Mirafra microptera Hume, 1873

• Alcippe dubia (Hume, 1874)

• Stachyridopsis rufifrons (Hume, 1873)

• Cyornis olivaceus Hume, 1877

• Oenanthe albonigra (Hume, 1872)

• Dicaeum virescens Hume, 1873

• Pyrgilauda blanfordi (Hume, 1876)

• Ploceus megarhynchus Hume, 1869

• Spinus thibetanus (Hume, 1872)

• Carpodacus stoliczkae (Hume, 1874)

• Gampsorhynchus torquatus Hume, 1874

• Sylvia minula Hume, 1873

• Sylvia althaea Hume, 1878

• Phylloscopus neglectus Hume, 1870

• Horornis brunnescens (Hume, 1872)

• Yuhina humilis (Hume, 1877)

• Pteruthius intermedius (Hume, 1877)

• Certhia manipurensis Hume, 1881

• Calandrella acutirostris Hume, 1873

• Pycnonotus fuscoflavescens (Hume, 1873)

• Pycnonotus erythropthalmos (Hume, 1878)

SubspeciesThe use of trinomials had not yet gone into regular usage during Hume's time. He used the term "local race".[50] The following subspecies are current placements of taxa that were named as new species by Hume.

• Alectoris chukar pallida (Hume, 1873)

• Alectoris chukar pallescens (Hume, 1873)

• Francolinus francolinus melanonotus Hume, 1888

• Perdicula erythrorhyncha blewitti (Hume, 1874)

• Arborophila rufogularis tickelli (Hume, 1880)

• Phaethon aethereus indicus Hume, 1876

• Gyps fulvus fulvescens Hume, 1869

• Spilornis cheela davisoni Hume, 1873

• Accipiter badius poliopsis (Hume, 1874)

• Accipiter nisus melaschistos Hume, 1869

• Rallina eurizonoides telmatophila Hume, 1878

• Gallirallus striatus obscurior (Hume, 1874)

• Sterna dougallii korustes (Hume, 1874)

• Columba livia neglecta Hume, 1873

• Macropygia ruficeps assimilis Hume, 1874

• Centropus sinensis intermedius (Hume, 1873)

• Otus spilocephalus huttoni (Hume, 1870)

• Otus lettia plumipes (Hume, 1870)

• Otus sunia nicobaricus (Hume, 1876)

• Bubo bubo hemachalanus Hume, 1873

• Strix leptogrammica ochrogenys (Hume, 1873)

• Strix leptogrammica maingayi (Hume, 1878)

• Athene brama pulchra Hume, 1873

• Ninox scutulata burmanica Hume, 1876

• Lyncornis macrotis bourdilloni Hume, 1875

• Caprimulgus europaeus unwini Hume, 1871

• Aerodramus brevirostris innominatus (Hume, 1873)

• Aerodramus fuciphagus inexpectatus (Hume, 1873)

• Hirundapus giganteus indicus (Hume, 1873)

• Lacedo pulchella amabilis (Hume, 1873)

• Pelargopsis capensis intermedia Hume, 1874

• Halcyon smyrnensis saturatior Hume, 1874

• Megalaima asiatica davisoni Hume, 1877

• Dendrocopos cathpharius pyrrhothorax (Hume, 1881)

• Picus erythropygius nigrigenis (Hume, 1874)

• Falco cherrug hendersoni Hume, 1871

• Pericrocotus brevirostris neglectus Hume, 1877

• Pericrocotus speciosus flammifer Hume, 1875

• Dicrurus andamanensis dicruriformis (Hume, 1873)

• Rhipidura aureola burmanica (Hume, 1880)

• Garrulus glandarius leucotis Hume, 1874

• Dendrocitta formosae assimilis Hume, 1877

• Corvus splendens insolens Hume, 1874

• Corvus corax laurencei Hume, 1873

• Coracina melaschistos intermedia (Hume, 1877)

• Coracina fimbriata neglecta (Hume, 1877)

• Remiz coronatus stoliczkae (Hume, 1874)

• Alauda arvensis dulcivox Hume, 1872

• Alaudala raytal adamsi (Hume, 1871)

• Galerida cristata magna Hume, 1871

• Pycnonotus squamatus webberi (Hume, 1879)

• Pycnonotus finlaysoni davisoni (Hume, 1875)

• Alophoixus pallidus griseiceps (Hume, 1873)

• Hemixos flavala hildebrandi Hume, 1874

• Hemixos flavala davisoni Hume, 1877

• Ptyonoprogne obsoleta pallida Hume, 1872

• Aegithalos concinnus manipurensis (Hume, 1888)

• Leptopoecile sophiae stoliczkae (Hume, 1874)

• Prinia crinigera striatula (Hume, 1873)

• Prinia inornata terricolor (Hume, 1874)

• Prinia sylvatica insignis (Hume, 1872)

• Orthotomus atrogularis nitidus Hume, 1874

• Rhopocichla atriceps bourdilloni (Hume, 1876)

• Pomatorhinus hypoleucos tickelli Hume, 1877

• Pomatorhinus horsfieldii obscurus Hume, 1872

• Pomatorhinus ochraceiceps austeni Hume, 1881

• Stachyridopsis rufifrons poliogaster (Hume, 1880)

• Alcippe poioicephala brucei Hume, 1870

• Pellorneum albiventre ignotum Hume, 1877

• Pellorneum ruficeps minus Hume, 1873

• Turdoides caudata eclipes (Hume, 1877)

• Garrulax caerulatus subcaerulatus Hume, 1878

• Trochalopteron chrysopterum erythrolaemumHume, 1881

• Trochalopteron variegatum simile Hume, 1871

• Minla cyanouroptera sordida (Hume, 1877)

• Minla strigula castanicauda (Hume, 1877)

• Heterophasia annectans davisoni (Hume, 1877)

• Chrysomma altirostre griseigulare (Hume, 1877)

• Rhopophilus pekinensis albosuperciliaris (Hume, 1873)

• Zosterops palpebrosus auriventer Hume, 1878

• Yuhina castaniceps rufigenis (Hume, 1877)

• Aplonis panayensis tytleri (Hume, 1873)

• Sturnus vulgaris nobilior Hume, 1879

• Sturnus vulgaris minor Hume, 1873

• Copsychus saularis andamanensis Hume, 1874

• Anthipes solitaris submoniliger Hume, 1877

• Cyornis concretus cyaneus (Hume, 1877)

• Ficedula tricolor minuta (Hume, 1872)

• Myophonus caeruleus eugenei Hume, 1873

• Geokichla sibirica davisoni (Hume, 1877)

• Dicaeum agile modestum (Hume, 1875)

• Cinnyris asiaticus intermedius (Hume, 1870)

• Cinnyris jugularis andamanicus (Hume, 1873)

• Aethopyga siparaja cara Hume, 1874

• Aethopyga siparaja nicobarica Hume, 1873

• Passer ammodendri stoliczkae Hume, 1874

• Lonchura striata semistriata (Hume, 1874)

• Lonchura kelaarti jerdoni (Hume, 1874)

• Linaria flavirostris montanella (Hume, 1873)

William Ruxton Davison, Curator of Hume's personal bird collection

William Ruxton Davison, Curator of Hume's personal bird collectionAn additional species, the large-billed reed-warbler Acrocephalus orinus was known from just one specimen collected by him in 1869 but the name that he used, magnirostris, was found to be preoccupied and replaced by the name orinus provided by Harry Oberholser in 1905.[51] The status of the species was contested until DNA comparisons with similar species in 2002 suggested that it was a valid species.[52] It was only in 2006 that the species was seen in the wild in Thailand, with a match to the specimens confirmed using DNA sequencing. Later searches in museums led to several other specimens that had been overlooked and based on the specimen localities, a breeding region was located in Tajikistan and documented in 2011.[53][54]

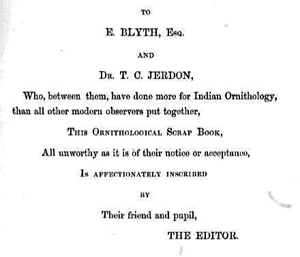

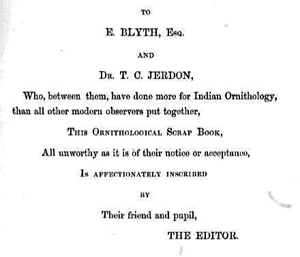

My Scrap Book: Or Rough Notes on Indian Oology and Ornithology (1869) Dedication of "My Scrap Book" to Blyth and Jerdon.[55]

Dedication of "My Scrap Book" to Blyth and Jerdon.[55]This was Hume's first major work on birds. It had 422 pages and accounts of 81 species. It was dedicated to Edward Blyth and Dr. Thomas C. Jerdon who, he wrote [had] done more for Indian Ornithology than all other modern observers put together and he described himself as their friend and pupil. He hoped that his book would form a nucleus round which future observation may crystallize and that others around the country could help him fill in many of the woeful blanks remaining in record. In the preface he notes:

...if these notes chance to be of the slightest use to you, use them; if not burn them, if it so please you, but do not waste your time in abusing me or them, since no one can think more poorly of them than I do myself.

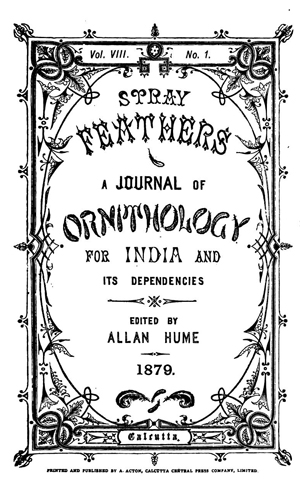

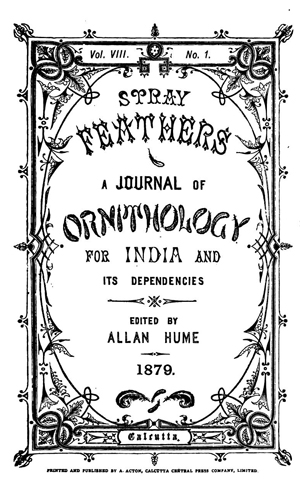

Stray FeathersHume started the quarterly journal Stray Feathers in 1872. At that time the only journal for the Indian region that published on ornithology was the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal and Hume published only two letters in 1870, mainly being a list of errors in the list of Godwin-Austen which had been reduced to an abstract.[56] He had wondered if there was merit to start a new journal and in that idea was supported by Stoliczka, who was an editor for the Journal of the Asiatic Society:

To return; the notion that Stray Feathers might possibly interfere in any way with our scientific palladium, the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, is much like that entertained in England, when I was a boy, as to the probable effects of Railways on road and canal traffic.

— Hume, 1874[57]

Cover of Stray Feathers

Cover of Stray FeathersThe President of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Thomas Oldham, in the annual address for 1873 wrote - "We could have wished that the author had completed the several works which he had already commenced, rather than started a new publication. But we heartily welcome at the same time the issue of 'Stray Feathers.' It promises to be a useful catalogue of the Editor's very noble collection of Indian Birds, and a means of rapid publication of novelties or corrections, always of much value with ornithologists."[58] Hume used the journal to publish descriptions of his new discoveries. He wrote extensively on his own observation as well as critical reviews of all the ornithological works of the time and earned himself the nickname of Pope of Indian ornithology. He critiqued a monograph on parrots, Die Papageien by Friedrich Hermann Otto Finsch suggesting that name changes (by "cabinet naturalists") were aimed at claiming authority to species without the trouble of actually discovering them. He wrote:

Let us treat our author as he treats other people's species. “Finsch!” contrary to all rules of orthography! What is that “s” doing there? “Finch!” Dr. Fringilla, MIHI! Classich gebildetes wort!!

— Hume, 1874[59]

Hume in turn was attacked, for instance by Viscount Walden, but Finsch became a friend and Hume named a species, Psittacula finschii, after him.[60][61]

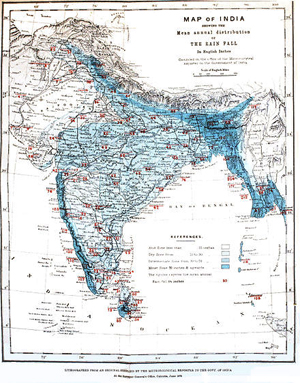

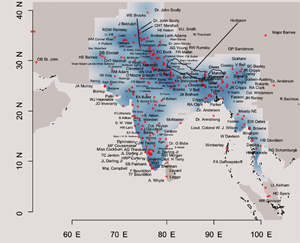

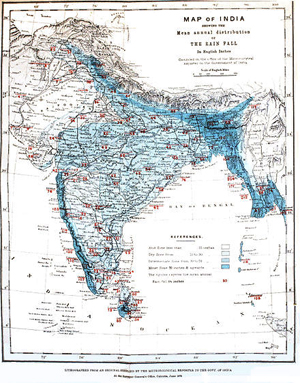

Hume was among the first to recognize an association between the avifaunal composition and rainfall distribution. This rainfall map was published in volume 8 of Stray Feathers (1878).

Hume was among the first to recognize an association between the avifaunal composition and rainfall distribution. This rainfall map was published in volume 8 of Stray Feathers (1878).In his younger days Hume had studied some geology from the likes of Gideon Mantell[62] and appreciated the synthesis of ideas from other fields into ornithology. Hume included in 1872, a detailed article on the osteology of birds in relation to their classification written by Richard Lydekker who was then in the Geological Survey of India.[63] The early meteorological work in India was done within the department headed by Hume and he saw the value of meteorology in the study of bird distributions. In a work comparing the rainfall zones, he notes how the high rainfall zones indicated affinities to the Malayan fauna.[64][65]

Hume sometimes mixed personal beliefs in notes that he published in Stray Feathers. For instance he believed that vultures soared by altering the physics ("altered polarity") of their body and repelling the force of gravity. He further noted that this ability was normal in birds and could be acquired by humans by maintaining spiritual purity claiming that he knew of at least three Indian Yogis and numerous saints in the past with this ability of aethrobacy.[66][67]