by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/1/20

Explanation of the Ashummeed Jugg.The Ashummeed Jugg does not merely consist in the Performance of that Ceremony which is open to the Inspection of the World, namely, in bringing a Horse and sacrificing him; but Ashummeed is to be taken in a mystic Signification, as implying, that the Sacrificer must look upon himself to be typified in that Horse, such as he shall be described, because the religious Duty of the Ashummeed Jugg comprehends all those other religious Duties, to the Performance of which all the Wise and Holy direct all their Actions, and by which all the sincere Prosessors of every different Faith aim at Perfection: The mystic Signification thereof is as follows: The Head of that unblemished Horse is the Symbol of the Morning; his Eyes are the Sun; his Breath the Wind; his wide-opening Mouth is the Bishwaner, or that innate Warmth which invigorates all the World; his Body typifies one entire Year; his Back Paradise; his Belly the Plains; his Hoof this Earth; his Sides the four Quarters of the Heavens; the Bones thereof the intermediate Spaces between the four Quarters; the Rest of his Limbs represent all distinct Matter; the Places where those Limbs meet, or his Joints, imply the Months and Halves of the Months, which are called Peche (or Fortnights;) his Feet signify Night and Day; and Night and Day are of four Kinds: 1st. The Night and Day of Brihma; 2d. The Night and Day of Angels; 3d, The Night and Day of the World of the Spirits of deceased Ancestors; 4th. The Night and Day of Mortals: These four Kinds are typified in his four Feet. The Rest of his Bones are the Constellations of the fixed Stars, which are the twenty-eight Stages of the Moon's Course, called the Lunar Year; his Flesh is the Clouds; his Food the Sand; his Tendons the Rivers; his Spleen and Liver the Mountains; the Hair of his Body the Vegetables, and his long Hair the Trees; the Forepart of his Body typifies the first Half of the Day, and the hinder Part the latter Half; his Yawning is the Flash of the Lightning, and his turning himself is the Thunder of the Cloud; his Urine represents the Rain; and his mental Reflection is his only Speech. The golden Vessels which are prepared before the Horse is let loose are the Light of the Day, and the Place where those Vessels are kept is a Type of the Ocean of the East; the silver Vessels which are prepared after the Horse is let loose are the Light of the Night, and the Place where those Vessels are kept is a Type of the Ocean of the West: These two Sorts of Vessels are always before and after the Horse. — The Arabian Horse, which on Account of his Swiftness is called Hy, is the Performer of the Journies of Angels; the Tajee, which is of the Race of Persian Horses, is the Performer of the Journies of the Kundherps (or good Spirits;) the Wazba, which is of the Race of the deformed Tazee Horses, is the Performer of the Journies of the Jins (or Demons;) and the Ashoo, which is of the Race of Turkish Horses, is the Performer of the Journies of Mankind: This one Horse, which performs these several Services, on Account of his four different Sorts of Riders, obtains the four different Appellations: The Place where this Horse remains is the great Ocean, which signifies the great Spirit of Perm-Atma, or the universal Soul, which proceeds also from that Perm-Atma, and is comprehended in the same Perm-Atma. The Intent of this Sacrifice is, that a Man should consider himself to be in the Place of that Horse, and look upon all these Articles as typified in himself; and, conceiving the Atma (or divine Soul) to be an Ocean, should let all Thought of Self be absorbed in that Atma."

This is the very Acme and Enthusiasm of Allegory, and wonderfully displays the picturesque Powers of Fancy in an Asiatic Genius. But it would not have been inserted at Length in this Place, if the Circumstance of letting loose the Horse had not seemed to bear a great Resemblance to the Ceremonies of the Scape-Goat; and perhaps the known Intention of this latter may plead for the like hidden Meaning in the former.

-- A Code of Gentoo Laws, Or, Ordinations of the Pundits, From a Persian Translation, Made From the Original, Written in the Shanscrit Language, by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed

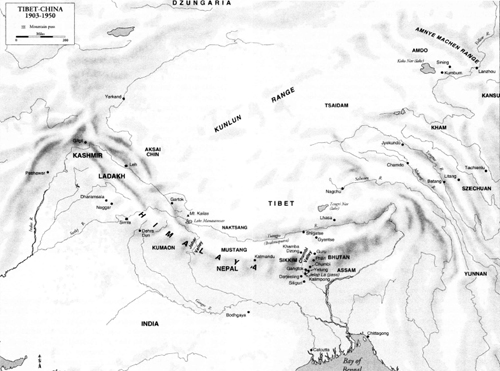

A somewhat droll and almost dramatic feast is the chase of the demon of ill-luck, evidently a relic of a former demonist cult. It is called "Chongju Sewang," and is held at Lhasa on the twenty-ninth and thirtieth days of the second month, though it sometimes lasts about a week. It starts after divine service. A priest represents a Grand Lama, and one of the multitude is masqueraded as the ghost-king. For a week previously he sits in the market-place with face painted half black and half white, and a coat of skin is put on his arm and he is called "King of the Years'" (? head). He helps himself to what he wants, and goes about shaking a black yak's tail over the heads of the people, who thus transfer to him their ill-luck.

This latter person then goes towards the priest in the neighbourhood of the cloister of La-brang and ridicules him, saying: "What we perceive through the five sources (the five senses) is no illusion. All you teach is untrue," etc., etc. The acting Grand Lama contradicts this; but both dispute for some time with one another; and ultimately agree to settle the contest by dice; the Lama consents to change places with the scape-goat if the dice should so decide. The Lama has a dice with six on all six sides and throws six-up three times, while the ghost-king has a dice which throws only one.

When the dice of the priest throws six six times in succession and that of the scape-goat throws only ones, this latter individual, or "Lojon" as he is called, is terrified and flees away upon a white horse, which, with a white dog, a white bird, salt, etc., he has been provided with by government. He is pursued with screams and blank shots as far as the mountains of Chetang, where he has to remain as an outcast for several months in a narrow haunt, which, however, has been previously provided for him with provisions.

We are told that, while en route to Chetang, he is detained for seven days in the great chamber of horrors at Sam-yas monastery filled with the monstrous images of devils and skins of huge serpents and wild animals, all calculated to excite feelings of terror. During his seven days' stay he exercises despotic authority over Sam-yas, and the same during the first seven days of his stay at Chetang. Both Lama and laity give him much alms, as he is believed to sacrifice himself for the welfare of the country. It is said that in former times the man who performed this duty died at Chetang in the course of the year from terror at the awful images he was associated with; but the present scape-goat survives and returns to re-enact his part the following year. From Chetang, where he stays for seven days, he goes to Lho-ka, where he remains for several months.

-- The Buddhism of Tibet, or Lamaism With Its Mystic Cults, Symbolism and Mythology, and in its Relation to Indian Buddhism, by Laurence Austine Waddell

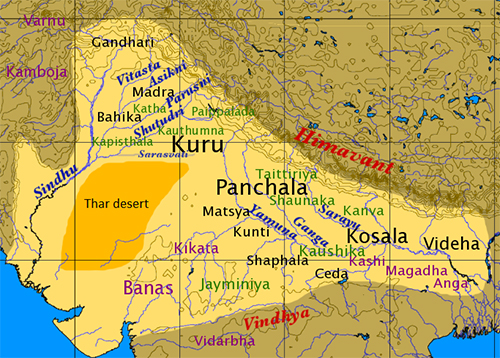

Ashwamedha yagna of Yudhisthira

The Ashvamedha (Sanskrit: अश्वमेध aśvamedha) is a horse sacrifice ritual followed by the Śrauta tradition of Vedic religion. It was used by ancient Indian kings to prove their imperial sovereignty: a horse accompanied by the king's warriors would be released to wander for a period of one year. In the territory traversed by the horse, any rival could dispute the king's authority by challenging the warriors accompanying it. After one year, if no enemy had managed to kill or capture the horse, the animal would be guided back to the king's capital. It would be then sacrificed, and the king would be declared as an undisputed sovereign.

The best-known text describing the sacrifice is the Ashvamedhika Parva (Sanskrit: अश्वमेध पर्व), or the "Book of Horse Sacrifice," the fourteenth of eighteen books of the Indian epic poem Mahabharata. Krishna and Vyasa advise King Yudhishthira to perform the sacrifice, which is described at great length. The book traditionally comprises 2 sections and 96 chapters.[1][2] The critical edition has one sub-book and 92 chapters.[3][4]

The ritual is recorded as being held by many ancient rulers, but apparently only by two in the last thousand years. The most recent ritual was in 1741, the second one held by Maharajah Jai Singh II of Jaipur. The original Vedic religion had evidently included many animal sacrifices, as had the various folk religions of India. Brahminical Hinduism had evolved opposing animal sacrifices, which have not been the norm in most forms of Hinduism for many centuries. The great prestige and political role of the Ashvamedha perhaps kept it alive for longer.

The sacrifice

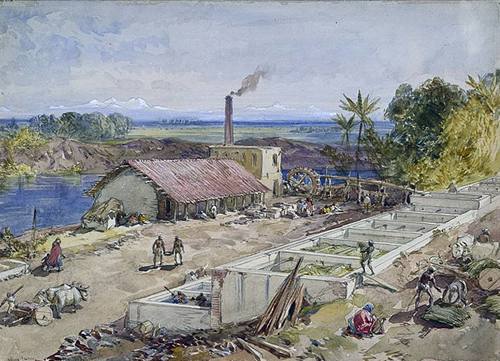

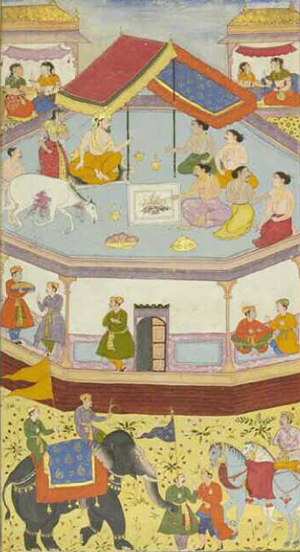

A 19th-century painting, depicting the preparation of army to follow the sacrificial horse. Probably from a picture story depicting Lakshmisa's Jaimini Bharata

The Ashvamedha could only be conducted by a powerful victorious king (rājā).[5][6] Its object was the acquisition of power and glory, the sovereignty over neighbouring provinces, seeking progeny and general prosperity of the kingdom.[7] It was enormously expensive, requiring the participation of hundreds of individuals, many with specialized skills, and hundreds of animals, and involving many precisely prescribed rituals at every stage.[8]

The horse to be sacrificed must be a white stallion with black spots. The preparations included the construction of a special "sacrificial house" and a fire altar. Before the horse began its travels, at a moment chosen by astrologers, there was a ceremony and small sacrifice in the house, after which the king had to spend the night with the queen, but avoiding sex.[9]

The next day the horse was consecrated with more rituals, tethered to a post, and addressed as a god. It was sprinkled with water, and the Adhvaryu, the priest and the sacrificer whispered mantras into its ear. A black dog was killed, then passed under the horse, and dragged to the river from which the water sprinkled on the horse had come. The horse was then set loose towards the north-east, to roam around wherever it chose, for the period of one year,[10] or half a year, according to some commentators. The horse was associated with the Sun, and its yearly course.[11] If the horse wandered into neighbouring provinces hostile to the sacrificer, they were to be subjugated. The wandering horse was attended by a herd of a hundred geldings, and one or four hundred young kshatriya men, sons of princes or high court officials, charged with guarding the horse from all dangers and inconvenience, but never impeding or driving it.[10] During the absence of the horse, an uninterrupted series of ceremonies was performed in the sacrificer's home.

After the return of the horse, more ceremonies were performed for a month before the main sacrifice. The king was ritually purified, and the horse was yoked to a gilded chariot, together with three other horses, and Rigveda (RV) 1.6.1,2 (YajurVeda (YV) VSM 23.5,6) was recited. The horse was then driven into water and bathed. After this, it was anointed with ghee by the chief queen and two other royal consorts. The chief queen anointed the fore-quarters, and the others the barrel and the hind-quarters. They also embellished the horse's head, neck, and tail with golden ornaments. After this, the horse, a hornless he-goat, and a wild ox (go-mrga, Bos gaurus) were bound to sacrificial stakes near the fire, and seventeen other animals were attached to the horse. A great number of animals, both tame and wild, were tied to other stakes, according to one commentator, 609 in total. The sacrificer offered the horse the remains of the night's oblation of grain. The horse was then suffocated to death.[10]

The chief queen ritually called on the king's fellow wives for pity. The queens walked around the dead horse reciting mantras. The chief queen then had to spend a night with the dead horse.[12]

On the next morning, the priests raised the queen from the place. One priest cut the horse along the "knife-paths" while other priests started reciting the verses of Vedas, seeking healing and regeneration for the horse.[13]

The Laws of Manu refer to the Ashvamedha (V.53): "The man who offers a horse-sacrifice every day for a hundred years, and the man who does not eat meat, the two of them reap the same fruit of good deeds."[14]

On Gupta coins

One type of the gold coins of the Gupta Empire kings Samudragupta (reigned c. 350-370 CE) and Kumaragupta (reigned c. 415-455 CE) commemorates their Ashvamedha sacrifices. The obverse shows the horse anointed and decorated for sacrifice, standing in front of a Yūpa sacrificial post, and is inscribed "The king of kings who has performed the Vajimedha sacrifice wins heaven after protecting the earth". The reverse shows a standing figure of the queen, holding a fan and a towel, and is inscribed "Powerful enough to perform the Ashvamedha sacrifice".[15]

Samudragupta, Ashvamedha horse; The queen, reverse of last

Samudragupta

Kumaragupta

Similar sacrifices elsewhere

Main article: Horse sacrifice

Many Indo-European branches show evidence for horse sacrifice, and comparative mythology suggests that they derive from a Proto-Indo-European ritual. Most appear to be funerary practices associated with burial, but for some other cultures there is tentative evidence for rituals associated with kingship. The Ashvamedha is the clearest evidence preserved, but vestiges from Latin and Celtic traditions allow the reconstruction of a few common attributes.

A similar ritual is found in Celtic tradition in which the king in Ireland conducted a rite of symbolic marriage with a sacrificed horse.[12] The October Horse Roman horse sacrifice was an annual event, and apparently the only time horses were sacrificed, rather than cattle or smaller animals.[16]

Horse sacrifices were performed among the ancient Germans, Armenians, Iranians,[17] Chinese, Greeks,[18] among others.

List of performers

Sanskrit epics and Puranas mention numerous legendary performances of the horse sacrifice.[19] For example, according to the Mahabharata, Emperor Bharata performed a hundred Ashvamedha ceremonies on the banks of Yamuna, three hundred on the banks of Saraswati and four hundred on the banks of the Ganga. He again performed a thousand Ashvamedha on different locations and a hundred Rajasuya.[20] Following the vast empires ruled by the Gupta and Chalukya dynasties, the practice of the sacrifice diminished remarkably.[5]

The historical performers of Ashvamedha include:

Monarch / Reign / Dynasty / Source

Pushyamitra Shunga / 185-149 BCE / Shunga / Ayodhya inscription of Dhanadeva and Malavikagnimitra of Kalidasa[21]

Sarvatata / 1st century BCE / Gajayana / Ghosundi and Hathibada inscriptions.[21] Some scholars believe Sarvatata to be a Kanva king, but there is no definitive evidence for this.[22]

Devimitra / 1st century BCE / Unknown / Musanagar inscription[21]

Satakarni I / 1st or 2nd century CE / Satavahana / Nanaghat inscription mentions his second Ashvamedha[23][21]

Vasishthiputra Chamtamula / 3rd century CE / Andhra Ikshvaku / Records of his son and grandson[24]

Shilavarman / 3rd century CE / Varshaganya J/ agatpur inscriptions mention his fourth Ashvamedha[21]

Pravarasena I / c. 270 – c. 330 CE / Vakataka / Inscriptions of his descendants state that he performed four Ashvamedha sacrifices[25]

Bhavanaga / 305-320 CE / Nagas of Padmavati / The inscriptions of Vakataka relatives of the Nagas credit them with 10 horse-sacrifices, although they do not name these kings.[21][24]

Vijaya-devavarman / 300-350 CE / Shalankayana / Ellore inscription[25][26]

Shivaskanda Varman / 4th century CE / Pallava / Hirahadagalli inscription[25]

Kumaravishnu / 4th century CE / Pallava / Omgodu inscription of his great-grandson[25]

Samudragupta / c. 335/350-375 CE / Gupta / Coins of the king and records of his descendants[25][27]

Kumaragupta I / 414 – 455 CE / Gupta / [28]

Madhava Varman / 440-460 CE / Vishnukundina / [24]

Dharasena / 5th century CE / Traikutaka / [26]

Krishnavarman / 5th century CE / Kadamba / [26]

Narayanavarman / 494–518 CE / Varman Legend of Bhaskaravarman's seals[29]

Bhutivarman / 518–542 CE / Varman / Barganga inscription[29]

Pulakeshin I / 543–566 CE / Chalukyas of Vatapi / [30]

Sthitavarman / 565–585 CE / Varman / [31]

Pulakeshin II / 610–642 CE /Chalukyas of Vatapi / [24]

Madhavaraja II (alias Madhavavarman or Sainyabhita) / c. 620-670 CE / Shailodbhava / Inscriptions[32][29]

Simhavarman (possibly Narasimhavarman I) / 630-668 CE / Pallava / The Sivanvayal pillar inscription states that he performed ten Ashvamedhas[25]

Adityasena / 655-680 CE / Later Gupta / Vaidyanatha temple (Deoghar) inscription[29]

Madhyamaraja I (alias Ayashobhita II) / c. 670-700 CE / Shailodbhava / Inscriptions;[33] one interpretation of the inscriptions suggests that he merely participated in the Ashvamedha performed by his father Madhavaraja II[29]

Dharmaraja (alias Manabhita) / c. 726-727 CE / Shailodbhava / Inscriptions; one interpretation of the inscriptions suggests that he merely participated in the Ashvamedha performed by his grandfather Madhavaraja II[29]

Rajadhiraja Chola / 1044–1052 CE / Chola / [34]

Jai Singh II / 1734 and 1741 CE / Kachwahas of Jaipur / Ishvaravilasa Kavya by Krishna-bhatta, a participant in Jai Singh's Ashvamedha ceremony and a court poet of his son Ishvar Singh[35][36]

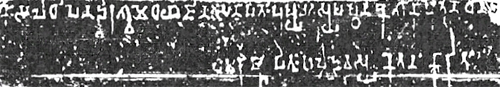

The Dhanadeva-Ayodhya inscription, 1st century BCE, mentions two Ashvamedha rituals by Pushyamitra in the city of Ayodhya.[37]

The Udayendiram inscription of the 8th century Pallava king Nandivarman II (alias Pallavamalla) states that his general Udayachandra defeated the Nishada ruler Prithvivyaghra, who, "desiring to become very powerful, was running after the horse of the Ashvamedha". The inscription does not clarify which king initiated this Ashvamedha campaign. Historian N. Venkataramanayya theorized that Prithvivyaghra was a feudatory ruler, who unsuccessfully tried to challenge Nandivarman's Ashvamedha campaign. However, historian Dineshchandra Sircar notes that no other inscriptions of Nandivarman or his descendants mention his performance of Ashvamedha; therefore, it is more likely that the Ashvamedha campaign was initiated by Prithvivyaghra (or his overlord), and Nandivarman's general foiled it.[38]

In Hindu revivalism

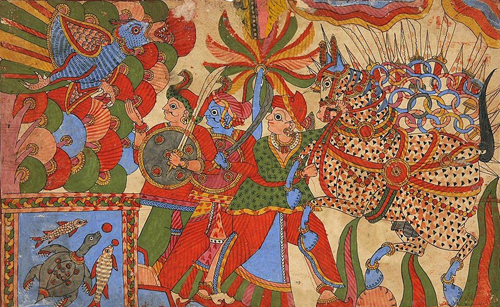

The horse Shyamakarna on the bank of Lake Dudumbhi, illustrating Jaimini's commentary on Ashvamedha, 19th century, Maharashtra

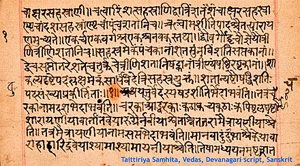

In the Arya Samaj reform movement of Dayananda Sarasvati, the Ashvamedha is considered an allegory or a ritual to get connected to the "inner Sun" (Prana)[11][39] According to Dayananda, no horse was actually to be slaughtered in the ritual as per the Yajurveda. Following Dayananda, the Arya Samaj disputes the very existence of the pre-Vedantic ritual; thus Swami Satya Prakash Saraswati claims that

the word in the sense of the Horse Sacrifice does not occur in the Samhitas [...] In the terms of cosmic analogy, ashva s the Sun. In respect to the adhyatma paksha, the Prajapati-Agni, or the Purusha, the Creator, is the Ashva; He is the same as the Varuna, the Most Supreme. The word medha stands for homage; it later on became synonymous with oblations in rituology, since oblations are offered, dedicated to the one whom we pay homage. The word deteriorated further when it came to mean 'slaughter' or 'sacrifice'.[40]

He argues that the animals listed as sacrificial victims are just as symbolic as the list of human victims listed in the Purushamedha.[40] (which is generally accepted as a purely symbolic sacrifice already in Rigvedic times).

All World Gayatri Pariwar since 1991 has organized performances of a "modern version" of the Ashvamedha where a statue is used in place of a real horse, according to Hinduism Today with a million participants in Chitrakoot, Madhya Pradesh on April 16 to 20, 1994.[41] Such modern performances are sattvika Yajnas where the animal is worshipped without killing it,[42] the religious motivation being prayer for overcoming enemies, the facilitation of child welfare and development, and clearance of debt,[43] entirely within the allegorical interpretation of the ritual, and with no actual sacrifice of any animal.

Reception

The earliest recorded criticism of the ritual comes from the Cārvāka, an atheistic school of Indian philosophy that assumed various forms of philosophical skepticism and religious indifference. A quotation of the Cārvāka from Madhavacharya's Sarva-Darsana-Sangraha states: "The three authors of the Vedas were buffoons, knaves, and demons. All the well-known formulae of the pandits, jarphari, turphari, etc. and all the obscene rites for the queen commanded in Aswamedha, these were invented by buffoons, and so all the various kinds of presents to the priests, while the eating of flesh was similarly commanded by night-prowling demons."[44]

Charvaka (Sanskrit: चार्वाक; IAST: Cārvāka), also known as Lokāyata, is an ancient school of Indian materialism. Charvaka holds direct perception, empiricism, and conditional inference as proper sources of knowledge, embraces philosophical skepticism and rejects ritualism, and supernaturalism. It was a very popular belief system in India before the emergence of Jain and Buddhist tradition.

Brihaspati is traditionally referred to as the founder of Charvaka or Lokāyata philosophy, although some scholars dispute this. During the Hindu reformation period in the 600 BCE, when Buddhism and Jainism arose, the philosophy was well documented and opposed by the new religions.[10] Much of the primary literature of Charvaka, the Barhaspatya sutras, were lost either due to waning popularity or other unknown reasons. Its teachings have been compiled from historic secondary literature such as those found in the shastras, sutras, and the Indian epic poetry as well as in the dialogues of Gautama Buddha and from Jain literature. However, there is text that may belong to the Charvaka tradition, written by the skeptic philosopher Jayarāśi Bhaṭṭa, known as the Tattvôpaplava-siṁha, that provides information about this school, albeit unorthodox.

One of the widely studied principles of Charvaka philosophy was its rejection of inference as a means to establish valid, universal knowledge, and metaphysical truths. In other words, the Charvaka epistemology states that whenever one infers a truth from a set of observations or truths, one must acknowledge doubt; inferred knowledge is conditional.

Charvaka is categorized as a heterodox school of Indian philosophy. It is considered an example of atheistic schools in the Hindu tradition...

In 8th century CE Jaina literature, Saddarsanasamuccaya by Haribhadra,Lokayata is stated to be the Hindu school where there is "no God, no samsara (rebirth), no karma, no duty, no fruits of merit, no sin."

The Buddhist Sanskrit work Divyavadana (ca. 200–350 CE) mentions Lokayata, where it is listed among subjects of study, and with the sense of "technical logical science". Shantarakshita and Adi Shankara use the word lokayata to mean materialism, with the latter using the term Lokāyata, not Charvaka...

The tenets of the Charvaka atheistic doctrines can be traced to the relatively later composed layers of the Rigveda, while substantial discussions on the Charvaka is found in post-Vedic literature. The primary literature of Charvaka, such as the Brhaspati Sutra is missing or lost. Its theories and development has been compiled from historic secondary literature such as those found in the shastras (such as the Arthashastra), sutras and the epics (the Mahabharata and Ramayana) of Hinduism as well as from the dialogues of Gautama Buddha and Jain literature.

Substantial discussions about the Charvaka doctrines are found in texts during 600 BCE because of emergence of competing philosophies such as Buddhism and Jainism. Bhattacharya posits that Charvaka may have been one of several atheistic, materialist schools that existed in ancient India during the 600 BCE...

The earliest Charvaka scholar in India whose texts still survive is Ajita Kesakambali. Although materialist schools existed before Charvaka, it was the only school which systematised materialist philosophy by setting them down in the form of aphorisms in the 6th century BCE. There was a base text, a collection sūtras or aphorisms and several commentaries were written to explicate the aphorisms. This should be seen in the wider context of the oral tradition of Indian philosophy. It was in the 600 BCE onwards, with the emergent popularity of Buddhism that ancient schools started codifying and writing down the details of their philosophy.

E. W. Hopkins, in his The Ethics of India (1924) claims that Charvaka philosophy predated Jainism and Buddhism, mentioning "the old Cārvāka or materialist of the 6th century BC". Rhys Davids assumes that lokāyata in ca. 500 BC came to mean "skepticism" in general without yet being organised as a philosophical school. This proves that it had already existed for centuries and had become a generic term by 600 BCE. Its methodology of skepticism is included in the Ramayana, Ayodhya kanda, chapter 108, where Jabāli tries to persuade Rāma to accept the kingdom by using nāstika arguments (Rāma refutes him in chapter 109):[44]O, the highly wise! Arrive at a conclusion, therefore, that there is nothing beyond this Universe. Give precedence to that which meets the eye and turn your back on what is beyond our knowledge. (2.108.17)...

Charvaka was a living philosophy up to the 12th century in India's historical timeline, after which this system seems to have disappeared without leaving any trace...

The Charvaka epistemology holds perception as the primary and proper source of knowledge, while inference is held as prone to being either right or wrong and therefore conditional or invalid. Perceptions are of two types, for Charvaka, external and internal. External perception is described as that arising from the interaction of five senses and worldly objects, while internal perception is described by this school as that of inner sense, the mind. Inference is described as deriving a new conclusion and truth from one or more observations and previous truths. To Charvakas, inference is useful but prone to error, as inferred truths can never be without doubt.[48] Inference is good and helpful, it is the validity of inference that is suspect – sometimes in certain cases and often in others. To the Charvakas there were no reliable means by which the efficacy of inference as a means of knowledge could be established.

Charvaka's epistemological argument can be explained with the example of fire and smoke. Kamal states that when there is smoke (middle term), one's tendency may be to leap to the conclusion that it must be caused by fire (major term in logic). While this is often true, it need not be universally true, everywhere or all the times, stated the Charvaka scholars. Smoke can have other causes. In Charvaka epistemology, as long as the relation between two phenomena, or observation and truth, has not been proven as unconditional, it is an uncertain truth. In this Indian philosophy such a method of reasoning, that is jumping to conclusions or inference, is prone to flaw. Charvakas further state that full knowledge is reached when we know all observations, all premises and all conditions. But the absence of conditions, state Charvakas, can not be established beyond doubt by perception, as some conditions may be hidden or escape our ability to observe. They acknowledge that every person relies on inference in daily life, but to them if we act uncritically, we err. While our inferences sometimes are true and lead to successful action, it is also a fact that sometimes inference is wrong and leads to error.Truth then, state Charvaka, is not an unfailing character of inference, truth is merely an accident of inference, and one that is separable. We must be skeptics, question what we know by inference, question our epistemology.

This epistemological proposition of Charvakas was influential among various schools of in Indian philosophies, by demonstrating a new way of thinking and re-evaluation of past doctrines. Hindu, Buddhist and Jain scholars extensively deployed Charvaka insights on inference in rational re-examination of their own theories...

Since none of the means of knowing were found to be worthy to establish the invariable connection between middle term and predicate, Charvakas concluded that the inference could not be used to ascertain metaphysical truths. Thus, to Charvakas, the step which the mind takes from the knowledge of something to infer the knowledge of something else could be accounted for by its being based on a former perception or by its being in error. Cases where inference was justified by the result were seen only to be mere coincidences.

Therefore, Charvakas denied metaphysical concepts like reincarnation, an extracorporeal soul, the efficacy of religious rites, other worlds (heaven and hell), fate and accumulation of merit or demerit through the performance of certain actions. Charvakas also rejected the use of supernatural causes to describe natural phenomena. To them all natural phenomena was produced spontaneously from the inherent nature of things.The fire is hot, the water cold, refreshing cool the breeze of morn;

By whom came this variety ? from their own nature was it born.

The Charvaka did not believe in karma, rebirth or an afterlife. To them, all attributes that represented a person, such as thinness, fatness etc., resided in the body. The Sarvasiddhanta Samgraha states the Charvaka position as follows,There is no other world other than this;

There is no heaven and no hell;

The realm of Shiva and like regions,

are fabricated by stupid imposters.

— Sarvasiddhanta Samgraha, Verse 8

Charvaka believed that there was nothing wrong with sensual pleasure. Since it is impossible to have pleasure without pain, Charvaka thought that wisdom lay in enjoying pleasure and avoiding pain as far as possible. Unlike many of the Indian philosophies of the time, Charvaka did not believe in austerities or rejecting pleasure out of fear of pain and held such reasoning to be foolish.

The Sarvasiddhanta Samgraha states the Charvaka position on pleasure and hedonism as follows,The enjoyment of heaven lies in eating delicious food, keeping company of young women, using fine clothes, perfumes, garlands, sandal paste... while moksha is death which is cessation of life-breath... the wise therefore ought not to take pains on account of moksha.

A fool wears himself out by penances and fasts. Chastity and other such ordinances are laid down by clever weaklings.

— Sarvasiddhanta Samgraha, Verses 9-12

Charvakas rejected many of the standard religious conceptions of Hindus, Buddhists, Jains and Ajivakas, such as an afterlife, reincarnation, samsara, karma and religious rites. They were critical of the Vedas, as well as Buddhist scriptures.

The Sarvadarśanasaṃgraha with commentaries by Madhavacharya describes the Charvakas as critical of the Vedas, materialists without morals and ethics. To Charvakas, the text states, the Vedas suffered from several faults – errors in transmission across generations, untruth, self-contradiction and tautology. The Charvakas pointed out the disagreements, debates and mutual rejection by karmakanda Vedic priests and jñānakanda Vedic priests, as proof that either one of them is wrong or both are wrong, as both cannot be right.

Charvakas, according to Sarvadarśanasaṃgraha verses 10 and 11, declared the Vedas to be incoherent rhapsodies whose only usefulness was to provide livelihood to priests. They also held the belief that Vedas were invented by man, and had no divine authority.

Charvakas rejected the need for ethics or morals, and suggested that "while life remains, let a man live happily, let him feed on ghee even though he runs in debt".

The Jain scholar Haribhadra, in the last section of his text Saddarsanasamuccaya, includes Charvaka in his list of six darśanas of Indian traditions, along with Buddhism, Nyaya-Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Jainism and Jaiminiya. Haribhadra notes that Charvakas assert that there is nothing beyond the senses, consciousness is an emergent property, and that it is foolish to seek what cannot be seen.

The accuracy of these views, attributed to Charvakas, has been contested by scholars...

There was no continuity in the Charvaka tradition after the 12th century. Whatever is written on Charvaka post this is based on second-hand knowledge, learned from preceptors to disciples and no independent works on Charvaka philosophy can be found.[43] Chatterjee and Datta explain that our understanding of Charvaka philosophy is fragmentary, based largely on criticism of its ideas by other schools, and that it is not a living tradition:"Though materialism in some form or other has always been present in India, and occasional references are found in the Vedas, the Buddhistic literature, the Epics, as well as in the later philosophical works we do not find any systematic work on materialism, nor any organised school of followers as the other philosophical schools possess. But almost every work of the other schools states, for refutation, the materialistic views. Our knowledge of Indian materialism is chiefly based on these...."

Buddhists, Jains, Advaita Vedantins and Nyāya philosophers considered the Charvakas as one of their opponents and tried to refute their views. These refutations are indirect sources of Charvaka philosophy. The arguments and reasoning approach Charvakas deployed were significant that they continued to be referred to, even after all the authentic Charvaka/Lokāyata texts had been lost. However, the representation of the Charvaka thought in these works is not always firmly grounded in first-hand knowledge of Charvaka texts and should be viewed critically.

-- Charvaka, by Wikipedia

According to some writers, ashvamedha is a forbidden rite for Kaliyuga, the current age.[45][46]

This part of the ritual offended the Dalit reformer and framer of the Indian constitution B. R. Ambedkar and is frequently mentioned in his writings as an example of the perceived degradation of Brahmanical culture.[47]

While others such has Manohar L. Varadpande, praised the ritual as "social occasions of great magnitude".[48] Rick F. Talbott writes that "Mircea Eliade treated the Ashvamedha as a rite having a cosmogonic structure which both regenerated the entire cosmos and reestablished every social order during its performance."[49]

See also

• Ashva, horse in Vedic culture

• October Horse in Roman religion

• Cruelty to animals

Footnotes

1. Ganguli, K.M. (1883-1896) "Aswamedha Parva" in The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa (12 Volumes). Calcutta

2. Dutt, M.N. (1905) The Mahabharata (Volume 14): Ashwamedha Parva. Calcutta: Elysium Press

3. van Buitenen, J.A.B. (1973) The Mahabharata: Book 1: The Book of the Beginning. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, p 478

4. Debroy, B. (2010) The Mahabharata, Volume 1. Gurgaon: Penguin Books India, pp xxiii - xxvi

5. Mansingh, Surjit. Historical Dictionary of India. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 68.

6. Rick F. Talbott 2005, p. 111.

7. Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 72.

8. Glucklich, 111-114

9. Glucklich, 111-112

10. Glucklich, 112

11. Roshen Dalal 2010, p. 399.

12. Thomas V. Gamkrelidze; Vjaceslav V. Ivanov (1995). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture. Part I: The Text. Part II: Bibliography, Indexes. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 402–403.

13. Rick F. Talbott 2005, p. 123.

14. The Laws of Manu, translated by Wendy Doniger with Brian K. Smith, p.104. Penguin Books, London, 1991

15. Glucklich, 111

16. Thomas V. Gamkrelidze; Vjaceslav V. Ivanov (1995). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture. Part I: The Text. Part II: Bibliography, Indexes. Walter de Gruyter. p. 70.

17. Rick F. Talbott 2005, p. 142.

18. Roshen Dalal 2010, p. 44.

19. David M. Knipe 2015, p. 234.

20. K M Ganguly 1896, pp. 130–131.

21. Dineshchandra Sircar 1971, p. 175.

22. Dinesh Chandra Shukla (1978). Early history of Rajasthan. Bharatiya Vidya Prakashan. p. 30.

23. David M. Knipe 2015, p. 8.

24. Jayantanuja Bandyopadhyaya 2007, p. 203.

25. Dineshchandra Sircar 1971, p. 176.

26. Upinder Singh 2008, p. 510.

27. David M. Knipe 2015, p. 9.

28. Ashvini Agrawal 1989, p. 139.

29. Dineshchandra Sircar 1971, p. 179.

30. David M. Knipe 2015, p. 10.

31. Karl J. Schmidt (20 May 2015). An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History. Taylor & Francis. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-317-47680-1.

32. Snigdha Tripathy 1997, p. 67.

33. Snigdha Tripathy 1997, pp. 74-75.

34. Rama Shankar Tripathi (1942). History of Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 466. ISBN 978-81-208-0018-2.

35. P. K. Gode (1953). "Some contemporary Evidence regarding the aśvamedha Sacrifice performed by Sevai Jayasing of Amber (1699-1744 A. D.)". Studies in Indian Literary History. 2. Singhi Jain Shastra Sikshapith. pp. 288–291. OCLC 2499291.

36. Catherine B Asher (2008). "Rethinking a Millennium: Perspectives on Indian History from the Eighth to the Eighteenth Century : Essays for Harbans Mukhia". In Rajat Datta (ed.). Excavating Communalism: Kachhwaha Rajadharma and Mughal Sovereignty. Aakar Books. p. 232. ISBN 978-81-89833-36-7.

37. Ayodhya Revisited by Kunal Kishore p.24

38. Dineshchandra Sircar 1962, p. 263.

39. as a bahuvrihi, saptāśva "having seven horses" is another name of the Sun, referring to the horses of his chariot.; akhandjyoti.orgArchived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine glosses 'ashva' as "the symbol of mobility, valour and strength" and 'medha' as "the symbol of supreme wisdom and intelligence", yielding a meaning of 'ashvamedha' of "the combination of the valour and strength and illumined power of intellect"

40. The Critical and Cultural Study of the Shatapatha Brahmana by Swami Satya Prakash Saraswati, p. 415; 476

41. Hinduism Today, June 1994 ArchivedDecember 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

42. "Ashwamedha Yagam in city". Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh. The Hindu. Oct 13, 2005. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

43. Ashwamedhayagnam.org ArchivedSeptember 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

44. Madhavacarya, Sarvadarsana-sangraha, English translation by E. B. Cowell and A. E. Gough, 1904 quoted in Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya (ed.), Carvaka/Lokayata: An Anthology of Source Materials and Some Recent Studies (New Delhi: Indian Council of Philosophical Research, 1990)

45. Rosen, Steven. Holy Cow: The Hare Krishna Contribution to Vegetarianism and Animal Rights. Lantern Books. p. 212.

46. The Vedas: With Illustrative Extracts. Book Tree. p. 62. horse sacrifice was prohibited in the Kali Yuga

47. Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, Writings and Speeches. p. 1376.

48. "History of Indian Theatre, Volume 1" by Manohar Laxman Varadpande, p.46

49. "Sacred Sacrifice: Ritual Paradigms in Vedic Religion and Early Christianity" by Rick F. Talbott, p. 133

References

• Ashvini Agrawal (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0592-7.

• Charles Drekmeier (1962). Kingship and Community in Early India. Stanford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8047-0114-3.

• David M. Knipe (2015). Vedic Voices: Intimate Narratives of a Living Andhra Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

• Dineshchandra Sircar (1962). Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (ed.). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

• Dineshchandra Sircar (1971). Studies in the Religious Life of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-2790-5.

• Jayantanuja Bandyopadhyaya (2007). Class and Religion in Ancient India. Anthem. ISBN 978-1-84331-332-8.

• K M Ganguly (1896). The Mahabharata of Krishna Dwaipayana Vyasa. Sacred Texts.

• Glucklich, Ariel (2007). The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195314052.

• Rick F. Talbott (2005). Sacred Sacrifice: Ritual Paradigms in Vedic Religion and Early Christianity. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1-59752-340-0.

• Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. ISBN 9780143414216.

• Snigdha Tripathy (1997). Inscriptions of Orissa. I - Circa 5th-8th centuries A.D. Indian Council of Historical Research and Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1077-8.

• Stephanie Jamison (1996). Sacrificed Wife / Sacrificer's Wife. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

• Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9788131711200.