A religion of the book? On sacred texts in Hinduismby Robert Leach

Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich

2014

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

AbstractIn this article I provide an overview of the identity, role and function of sacred texts in Hinduism. Hinduism’s tremendous diversity extends to the numerous ways in which different types of texts have been identified as sacred and used by Hindu practitioners. It would be a mistake to attempt to summarise the role of sacred texts in the lives of Hindus, since different texts have had different roles and performed different functions. In the following, therefore, I address what I identify as the four major types or categories of sacred text in Hinduism independently of each other, while noting the commonalities they share, and some of the ways in which texts belonging to the different categories have engaged with one another. The first three of the four categories of text I address consist of Sanskrit works, and the names of the categories are Sanskrit terms which have been applied by Hindus to their own literature (Veda/Śruti; Smṛti; Tantra, Āgama and Stotra). In the final section, I depart from using “insider” terminology and address “sacred texts in vernacular languages”.

Keywords: Hinduism, sacred text, scripture

IntroductionThis article is intended as an overview of the identity, role and function of sacred texts in Hinduism. Such an endeavour is beset with potential difficulties, not least in that

Hinduism is itself a modern term, not used before the latter half of the 18th century, and with no obvious equivalents in Indic languages before that time. Applying the term Hinduism to the past, then, is frequently problematic, though in general modern scholarship is in agreement that there are important continuities between the present-day phenomenon of Hinduism and codes of ritual practice, narrative traditions and religious customs that emerged in South Asia in the second half of the first millennium before the Common Era (BCE).

Identifying the “scriptural” or “sacred” literature of Hinduism is also significantly more complex than with other major religions such as Buddhism, Christianity, Judaism and Islam. Hinduism has no historical founder, no universally recognised hierarchy of authority, no universally adhered-to teachings, practices or beliefs, and there is no single sacred text to which all Hindus pay tribute. Using concepts such as “scripture” and “sacred text” creates its own problems when confronting the diverse textual traditions and linguistic cultures that are a part of Hinduism, and for this reason, I structure the following account around terms which Hindus themselves have used. These terms belong to Sanskrit, the oldest of South Asia’s living languages, and the language in which by far the most influential and widely disseminated texts in Hinduism, at least until the middle of the second millennium CE, are composed. The overwhelming priority given to Sanskrit literature in the following account is itself not unproblematic, since the vast majority of the people we retrospectively identify as Hindu have not used or understood this language. However, it is also unavoidable given that Sanskritic culture has left by far the largest literary record of any translocal, premodern language in South Asia, and that those excluded from this culture often left no record at all.The Vedas and ŚrutiThe period during which the many texts included within the Veda (literally “The Knowledge”) were composed, collected and arranged into a canon lasted approximately 1200 years (c. 1600-400 BCE). The Vedic texts were orally composed and were transmitted from teacher to pupil, as they are to this day in some parts of South Asia, without the aid of script.1 This has necessitated exceptional feats of memorisation and an extremely strict emphasis on correct recitation. Although archaeology is increasingly shedding light on aspects of Vedic society and religion, these texts are our most important source of information about the Vedic period.

Whilst precise dates for individual Vedic texts are extremely difficult to establish, and are likely to remain so, the chronology of their composition, and of the distinct historico-linguistic layers internal to individual texts, is less so, and has persisted as a major focus of scholarly research since the pioneering philological work of the great

German Indologist Hermann Oldenberg (1854-1920).

It was Oldenberg, also, who first mapped in detail the southeastward expansion during the Vedic period of the Sanskrit speaking “Āryans” (ārya, “noble”) whose priestly class composed the Vedas. More recent scholarship has sought to trace this movement with greater precision and to explain the reasons for its occurrence. Since

the majority of the texts are oriented towards ritual practice, and comprise mostly unsystematically formulated liturgical material for the performance of the Vedic fire sacrifice, information about Vedic society, myth, religious belief, the intricacies of ritual, and canon formation, has to be laboriously extracted from the texts, and a great deal of past scholarship on the Vedas has been devoted to piecing together such information.

The earliest and most prestigious text within the Vedic canon is the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā (“Collection of the Knowledge of Verses”), an anthology of 1,028 poems arranged in ten books or “cycles” (maṇḍala), the vast majority of which were composed in the Greater Punjab in the northwest of the subcontinent between c. 1600 and 1200 BCE.2 These “poems” consist primarily of verses of praise and invocation,

addressed to various gods and local tribal chieftains, which were intended for recital at the annual Soma sacrifice, centred on Indra and celebrated at New Year. Principal among the gods addressed are Indra, the god of war and paradigmatic Āryan alpha male; Agni, the deified ritual fire into which sacrificial offerings to the gods are made; and Soma, the deified sacred drink (and the plant on which the drink is based).The poems often contain the names of their authors, as well as the names of the clans or tribes to which these authors belonged. These poets did not intend their compositions to be collected alongside poems by members of other tribes, with whom there was often conflict, and to be anthologised in the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā. This occurred in a later period (c.1200-1000 BCE) in the region of Kuru, southeast of the Greater Punjab, once Kuru kings had unified most of the 50 or so Ṛgvedic tribes to form what has been called the first “state” on Indian soil. This period remains something of a dark age in Indian historiography, but its importance to subsequent developments in South and Southeast Asian society and religion is paramount, since

it was in this time and place that the priestly class, the Brahmins, formed an alliance with the warrior nobility and, as documented in one of the latest Ṛgvedic poems, began to promote the idea that society consists of four social classes. It was also here that

Ṛgvedic ritual practices were systematically reformulated in the creation of the new, elaborate Śrauta rites, some of which are performed in traditional parts of India and Nepal to this day.

Śrauta is a Sanskrit word that means "belonging to śruti", that is, anything based on the Vedas of Hinduism. It is an adjective and prefix for texts, ceremonies or person associated with śruti. The term, for example, refers to Brahmins who specialise in the śruti corpus of texts, and Śrauta Brahmin traditions in modern times can be seen in Kerala and Coastal Andhra.

-- Śrauta, by Wikipedia

These innovations resulted in the

production of new ritual texts which were assembled according to the division of priestly labour in the new rites:

the Sāmavedasaṃhitā (“Collection of the Knowledge of Melodies”) being the property of the priests responsible for singing the verses of the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā; 3 the Yajurvedasaṃhitā (“Collection of the Knowledge of Ritual Formulae”) that of the priests who perform most of the ritual actions, accompanying them with the recitation of ritual formulae (mantra); and the slightly later, and to many minds inferior,4 Atharvavedasaṃhitā (“Collection of the Knowledge of [the sage] Atharvan”) that of the priests responsible for rectifying any mistakes in the performance with the recitation of incantations. Each of these collections borrowed and adapted verses from the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā.5

The Vedic Saṃhitās (Ṛg-, Sāma-, Yajur-, Atharva-) are the foundational texts of the four Vedas: the Ṛgveda, Sāmaveda, Yajurveda and Atharvaveda. During the next five or six hundred years the priests of each Veda considerably enlarged their textual corpus by composing numerous other works. These fall into four main text-types, listed here according to the approximate chronology of their composition: Brāhmaṇa (exegetical texts, interpreting the rituals and explaining their hidden meanings); Āraṇyaka (“wilderness texts”, discussing the more secret and dangerous rituals); Upaniṣad (secret teachings, containing early metaphysical speculation and introducing important new ideas into the Vedic worldview such as rebirth, the character of which is dependent on the quality of one’s actions (karma), and mokṣa, liberation from rebirth); and Kalpasūtra (discussed below). To further complicate issues, since the time succeeding the anthologisation of the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā, all Vedic texts, including the Saṃhitās, have existed in multiple versions – a consequence of local differences in ritual and pronunciation between different groups of Brahmins within each Veda. These differences led to the recognition of separate Vedic schools (śākhā), each of them associated with a particular Brahminical community in a particular geographic area. This meant that, for virtually the entirety of the Vedic period, there was no Vedic “canon” to speak of, only a canon of texts accepted by each school (Witzel 1997).

This situation changed around the end of the Vedic period (c. 500-400 BCE), when a final process of Vedic canon-formation took place in northeast India (the region of modern-day Avadh and Bihar). Here, all texts, other than the Kalpasūtras,6 belonging to all schools in each of the four Vedas were declared [by who?] to be equally authoritative and part of the unitary Vedic canon, from this time forward spoken of as “the Veda” or Śruti. Very little was added subsequently. The term śruti, meaning “that which is heard”, indicates the new idea that the unitary Veda has no author/s, but was revealed to and seen by inspired primordial seers (ṛṣi) who recited it to their pupils – thus, the Veda has been heard by all generations of Veda-reciters subsequent to the first. The system of Vedic exegesis which asserted the unity and authorlessness of the Veda became known as the Mīmāṃsā. Later Mīmāṃsā authors argued for the eternality and authorlessness of the Veda, and of the sacred Sanskrit language, on the grounds that since there is no recollection of an author (or first reciter), we have no basis to assume the existence of one, or reason to doubt that persons in the past learnt the Veda just as those in the present do, i.e. by hearing it recited by a teacher (McCrea 2011). The idea of the eternality and authorlessness of the Veda was very influential, and was later accepted by several important philosophical schools, including those located within the tradition of Vedānta, based on the exegesis of the Upaniṣads. However, it was not accepted by all. Monotheistic traditions first referred to in the later portions of the Sanskrit Mahābhārata (c. 3rd-4th Century CE), attributed authorship of the Veda to God, as did, from around the 6th century CE, the influential philosophical school of Nyāya.Charvakas, according to Sarvadarśanasaṃgraha verses 10 and 11, declared the Vedas to be incoherent rhapsodies whose only usefulness was to provide livelihood to priests. They also held the belief that Vedas were invented by man, and had no divine authority.-- Charvaka, by Wikipedia

A quotation of the Cārvāka from Madhavacharya's Sarva-Darsana-Sangraha states: "The three authors of the Vedas were buffoons, knaves, and demons. All the well-known formulae of the pandits, jarphari, turphari, etc. and all the obscene rites for the queen commanded in Aswamedha, these were invented by buffoons, and so all the various kinds of presents to the priests, while the eating of flesh was similarly commanded by night-prowling demons."-- Ashvamedha, by Wikipedia

The Veda has occupied an ambiguous position in Hinduism. On the one hand, many Hindus have proclaimed it their most authoritative and sacred body of literature. On the other, for the past two thousand years its contents have been almost completely unknown to the vast majority of Hindus, and have had virtually no relevance to their religious practices. In the last centuries before the Common Era, access to the Vedic texts was limited to male members of the three highest social classes, and since at least the second century CE, Hindu law-makers have declared that only male Brahmins are eligible to study the Veda. Between then and now, the great majority of the people we retrospectively identify as “Hindu” have been deliberately excluded from the Veda, and for most of this period we have little means of knowing whether such people accepted its authority. In ancient India, the maintenance of the Veda’s exclusivity was largely dependent on two factors: first, that it was prohibited to commit the Vedic texts to writing; second, that Brahmins were the guardians not only of the Vedas, but also of Sanskrit. By excluding all except male Brahmins from learning Sanskrit, the Veda was kept out of the majority’s reach. However, after the Sanskrit of the Vedas had developed, in the last centuries BCE, into the distinct, post-Vedic “Classical Sanskrit”, the content of the Vedas became inaccessible even to many Brahmins. Already in the Mānavadharmaśāstra, a Brahminical text composed probably around the 2nd century CE (Olivelle 2004), there is a reference to Brahmins who recite the Veda but do not understand it, and ethnographies attest to the existence of such persons today. This neglect of the content of the Vedas, together with the sustained emphasis on their correct recitation, signals

the prevalent belief that the sacredness of these texts is in their sounds rather than their meaning. Thus, to recite correctly, or to hear such a recital, is intrinsically efficacious.

According to Watts (2006), texts function as scriptures through the ritualisation of three primary “dimensions”: semantic, performative and iconic. If we apply this typology to the Veda,

for the majority of its history we can say that its semantic dimension has counted for very little, and that its performative dimension has been ritualised to by far the greatest degree. There is also textual evidence starting from

around the end of the first millennium CE that, in spite of continued prohibitions against writing down the Vedas in some quarters, manuscripts of Vedic texts have been worshipped by theistic traditions, normally alongside other manuscripts, as physical manifestations of god’s knowledge. However, this practice appears never to have been the predominant mode of engaging with Vedic texts.Finally, the authority of the Veda has also been implemented outside of the ritual context. Perhaps the most striking example of this is that, up until modern times,

Hindu legal traditions have affirmed that the Veda is, theoretically, the highest authority in all matters pertaining to correct behaviour (dharma), both public and private. In practice, though, the highest authority has in fact rested with an elite group of specialists in such matters, namely “those who know the Veda”, and the legitimacy of these specialists’ pronouncements on legal issues has been determined a priori by the identity of their authors as knowers of the Veda, rather than a posteriori by appeal to particular passages in Vedic texts. In various different ways, the Veda has provided a transcendent source of authority for Hindu traditions.SmṛtiAs a textual category, Smṛti, meaning literally “memory, remembrance”, emerged later than Śruti and has had a much broader purview. Before it came to denote a specific body of literature, the term smṛti indicated “remembered norms” viz. “tradition”, especially as an authoritative source of knowledge, alongside the Veda, in matters relating to proper conduct (dharma). When it came to refer to texts, during the 2nd century BCE at the earliest, Smṛti referred exclusively to the genre of Dharmaśāstra (discussed below), and this appears to have remained the case for several centuries (Brick 2006). While both the early history of Smṛti and its later elaboration and rationale in Mīmāṃsā apologetics have been studied in detail in recent years, there is as yet no scholarly consensus as to precisely when, and with what justification, texts other than the Dharmaśāstras began to be included within the category. However, it is clear that the definition proposed by

the 5th century Mīmāṃsā author Śabara allows a considerably broader conception of Smṛti than had been admitted in earlier times. In his commentary on the foundational text of his school, the Mīmāṃsāsūtra (c. 200 BCE?), Śabara argues that Smṛti designates those texts which retain the essential purport (although not the exact wording) of Vedic texts which have been lost or forgotten, but whose former existence can be inferred from the fact that authoritative persons (i.e. Vedic Brahmins) still follow their dictates. Seen in this way, as Pollock (1997) points out, Smṛti texts are themselves Vedic. This definition of Smṛti opened up the category to such an extent that it was never really closed thereafter, and there has been no universal agreement since Śabara as to which texts can be included as Smṛti, and which cannot. In the following, I will address the few texts which are generally held to be uncontroversially included within this category.

i.) Śāstra: Vedāṇga and DharmaśāstraIn modern Sanskrit-English dictionaries, the term śāstra, from the verbal root śās-, “to instruct”, is commonly given as a Sanskrit term for scripture. This may be partially justified insofar as it was used, from an early period, to denote the Veda, but in reality Śāstra designates a much broader class of texts, many of which would not ordinarily be understood as “scripture”, however vaguely defined. The term appears to have originally signified the technical treatises dealing with the six disciplines recognised as being ancillary to the study of the Veda (Olivelle 2010). The six disciplines, known collectively as Vedānga (“the limbs of the Veda”), are

ritual (kalpa), astrology and astronomy (jyotiṣa), phonetics (śikṣā), prosody (chandas), etymology (nirukta), and grammar (vyākaraṇa). The authoritative texts which address these disciplines,

nearly all of which were composed after the Vedic period, are generally acknowledged to have been authored by humans.7 The earliest of these belong to the genre of Kalpasūtra (“Aphoristic Rules on Ritual”) -– the only Vedāṅga works which will detain us here -– in which there are three kinds of texts: Śrautasūtra (instruction manuals for the performance of public Vedic rites); Gṛhyasūtra (appended to the Śrautasūtra; manuals for domestic rites, especially the rites of passage); and Dharmasūtra (normative and descriptive guides to all aspects of correct individual and social conduct as well as to matters relating to civil and criminal law). Although the Kalpasūtras are Vedic in the sense that they are composed in Vedic Sanskrit and are identified as belonging to one or other of the Vedic schools (śākhā), they have never been considered a part of Śruti. This is most likely a consequence of their relatively late composition and of the fact that they are essentially instruction manuals for the correct performance of actions enjoined in the earlier literature. However, although they have been excluded from what was originally (and in some senses remains) the most authoritative body of Sanskrit literature,

the Kalpasūtras have arguably played a more important role in the day-to-day lives of Hindus than has any Śruti text. In order to explain this, it will be helpful to briefly address the Śrautasūtras and Gṛhyasūtras together, and then to look at the Dharmasūtras.

Although plenty of information concerning the Śrauta rites can be extracted from the earlier Brāhmaṇas, these texts do not offer priests detailed, step-by-step guides to carrying out the rituals. This is the reason for which the Śrautasūtras were composed and have been transmitted between generations of priests for two and a half thousand years.

Unlike the Śruti texts, there are no intrinsic benefits to be had from reciting and hearing or reading the Vedic Sūtras other than the communication and acquisition of the information they contain – their value is in their content.8 As many of the Śrauta rites have been replaced by other forms of ritual (see below) and have become obsolete, or only rarely performed, so the

Śrautasūtras have declined in importance. The Gṛhyasūtras, on the other hand, have retained a more central role in the lives of Hindus, a consequence of their subject matter – domestic ritual – and the greater breadth of their intended audience – male householders belonging to the three highest social classes. Chief among the domestic rites enjoined in the Gṛhyasūtras are the so-called rites of passage or, better,

“life-cycle rites” (saṃskāra), the most important of which are those performed at the conception of the embryo, birth, initiation into Vedic study, marriage, death, and the worship of the departed ancestor. Each of these are still performed today within traditional Brahminical families.

Although the content of the Dharmasūtras (“Aphoristic Rules on Proper Conduct”) overlaps to a considerable degree with that of the Gṛhyasūtras, containing as they do a wealth of information on ritual performance, especially on the life-cycle rites and the reparatory rites to be performed in case of mistakes in the ritual procedure, these texts also came to represent a tradition independent from the other Vedic Kalpasūtras, and indeed from the Vedic schools in general. The name of this independent tradition is Dharmaśāstra, and it is principally constituted by the Dharmasūtras, orally composed from c. 300-50 BCE (only four of these texts are extant), and several later works in verse, principal among which is the Mānavadharmaśāstra (“The Law Code of Manu”), also called Manusmṛti, most likely composed during the 2nd century CE. These texts offer both prescriptive and descriptive accounts of correct ritual, social and ethical behaviour, the first two of which differ according to one’s social class and the stage of life one is at. More than religious belief or cultural custom, it is the dharma of the Dharmaśāstra that has been central to the identity of Hinduism as a religion.ii.) Itihāsa and PurāṇaThe category of Itihāsa (“[narratives which tell of] the way things were”) includes India’s two great epics, the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa. Both of these have existed, for over two thousand years, in a variety of artistic genres including dance, theatre, film and television, as well as in numerous literary versions in many of the vernacular languages of India and Southeast Asia.9 In both cases,

their earliest extant forms are immensely long Sanskrit texts in verse, the bulk of which were orally composed over several centuries between c. 400 BCE–400 CE.10 This period saw myriad changes in the religious and political culture of northern and central India, many of them brought about by the rise to prominence of Buddhism and, to a lesser extent, Jainism. These changes and their far-reaching consequences are too numerous to list here, though mention should be made of

the transformation of the Vedic priesthood (the Brahmins) into proponents of a tremendously successful religious and socio-political ideology based on Brahminical superiority (see Dharmaśāstra),

and of the emergence of monotheistic traditions which, without wholly repudiating the authority of the Veda and its sacrificial cult, established new forms of worship centred upon the veneration of images of god in temples and at shrines. The foundations laid by these innovations gave support to a religious culture which is retrospectively identified as “Hindu” as distinct from “Vedic”.Although

the Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa include, though by no means confine themselves to, much of the same sort of religious, ethical and metaphysical doctrine as can be found in earlier Sanskrit literature, they do so within a framework

derived from more popular (as opposed to priestly) storytelling traditions. Both were recited and performed by bards at the courts of rulers and, unlike the Veda, they were not memorised word for word but could incorporate new themes, subplots and characters in each retelling – a detail that accounts for their long gestation periods as well as their great length.

At some stage around the beginning of the Common Era, both texts began to be written down, and their transmission passed into the hands of Brahmins. However, unlike the texts covered thus far in this article,

the Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa claim to address themselves to women as well as men, and to members of all social classes. As with the Vedas, regional and cultural differences among the Brahmins responsible for transmitting the Sanskrit epics led to there being numerous versions of both texts, and both have been handed down in two principal recensions, one from the north and one from the south of India.

In the 20th century, Indian scholars compiled critical editions of the Sanskrit manuscript traditions of both texts (in the case of the Mahābhārata, 1,259 manuscripts were collated) and much of the subsequent scholarship on Itihāsa has been based on these editions. While the identification and dating of the two texts’ multiple layers has dominated philological work, there have also been numerous recent studies on the religious, philosophical, political and aesthetic dimensions of the epic traditions, as well as, for instance, structuralist and gender-based approaches to epic narratives.

The central story of the Mahābhārata tells of a bitter succession conflict, culminating in an 18-day war, between two sets of cousins for the ancestral realm of the Bhārata clan, the kingdom of Kurukṣetra in northern India. The most celebrated (and studied and translated) section of the Mahābhārata is the Bhagavadgītā (“The Song of the Lord”), which has often been treated, both by medieval commentators and modern scholars, as an independent text.11 As with the Mahābhārata in general, scholarship on the Bhagavadgītā has been dominated on the one hand by philological approaches, and on the other by approaches which take the text as a meaningful whole and interpret it according to different theoretical perspectives.12

The Gītā, as it is affectionately known, takes place about midway through the story as the two sides are lining up for battle, and it consists mostly of Kṛṣṇa’s exhortation to Arjuna, one of the major heroes of the Mahābhārata, to go forth and fight. Arjuna’s unwillingness to do so derives from the fact that many of his family members and former teachers are among the enemy. Kṛṣṇa, who is ostensibly Arjuna’s charioteer, reveals himself to be the supreme god, manifest on earth in order to restore dharma. His exhortation primarily involves a discussion of traditional concepts (e.g. sacrifice, dharma and karma) set within a new monotheistic framework. In several places the Gītā describes itself as an upaniṣad, thus laying claim to the status of Śruti, and indeed for most Vaiṣṇavas (worshippers of Viṣṇu), and for many non-Vaiṣṇava Hindus, it is among the most sacred of all texts, and is in some parts of India an object of temple worship.

Scholars generally agree that the identification of Kṛṣṇa with Viṣṇu belongs to the latest layers of the Mahābhārata (it is not found in the Gītā itself). It is also in these later layers that the Mahābhārata calls itself the “fifth Veda” and claims the mythical seer Vyāsa as its author.

The Rāmāyaṇa (“The Career of Rāma”), which tells the story of the exemplary warrior-prince Rāma and his retrieval of his devoted wife Sītā from her evil abductor King Rāvaṇa, also claims in one of the apparently later layers of the text that it is equal in authority to the Veda. The Rāmāyaṇa, though, presents itself as a literary work, indeed as the very first work of poetry, composed by the inspired poet-seer Vālmīki, which perhaps explains why

F. Max Müller, in his preface to The Sacred Books of the East (1879) declared that it is not a “Sacred Book”, calling it instead a “national epic”. Certainly the Rāmāyaṇa has held something akin to the status of national epic –- as Goldman and Sutherland Goldman (2010) write, “Its episodes and characters are known to every stratum of [Indian] society, every region of the country, and the adherents of every religion.” However, i

t has been interpreted especially as a treatise depicting the ideal Hindu state, a sort of poetical rendering of Dharmaśāstra, and has been used by Hindu rulers, especially against Indian followers of Islam,

to justify a particular idea of divine Hindu kingship. Further, its influence extends well beyond South Asia, as is evident from the fact that versions of the Rāmāyaṇa have been written in, for instance, Old Javanese (9th-10th century), Khmer (16th/17th century), and Thai (18th century). Moreover, its hero

Rāma is worshipped by millions of Hindus, either as the supreme god or as an incarnation (avatāra) of Viṣṇu. There are temples to Rāma, as well as depictions of scenes from the Rāmāyaṇa on temple walls, all over India, as well as numerous temples to its other central characters.

For many millions of the Hindus who worship in these, the Rāmāyaṇa is the exemplary narrative of god’s life as a man engaged in the destruction of evil and the restoration of dharma. Like the Mahābhārata, sections of the text are regularly declaimed at festivals and in temples across South Asia, a practice which is considered meritorious both for the reciters and the audience, even if the majority among the latter do not understand Sanskrit.

The term Purāṇa (“Ancient [Tales]”) denotes a vast body of mostly Sanskritic literature which began to be written down in the early centuries of the Common Era, as well as a vibrant but little-studied performative tradition in various vernacular languages which continues to this day.13 According to tradition, Vyāsa, the mythical author of the Mahābhārata, is also the author of all the Purāṇas. There are said to be 18 Major and 18 Minor Purāṇas though in reality there are many hundreds of texts in this genre.

Like the Sanskrit epics, the Purāṇas align themselves with the Veda, the rituals and myths of which they appropriate, adapt and expand to fit with their own monotheistic (or, better, henotheistic) theology.14 As well as appropriating Vedic rituals and myths, the Purāṇas also consciously appropriate the Veda’s scriptural status, and many Purāṇas explicitly call themselves Purāṇaveda and identify themselves as transmitting the infallible knowledge of the Veda, in the form of Purāna, to the general populace (Smith 1994). Thus, in common with Itihāsa, the Purāṇas claim to be accessible to women and to members of all four social classes (varṇa). Unlike the epics, these texts do not revolve around a central narrative:

their contents are a miscellaneous collection of complex cosmologies, elaborate genealogies, stories of the exploits of deities and kings, and descriptions of law codes, rituals and pilgrimages to holy places (many of which are still adhered to or undertaken today). Some of these texts are very long (in several cases considerably longer than, for instance, the Rāmāyaṇa), though

they are not intended to be recited or read from beginning to end.15

In keeping with the idea that the Purāṇas occupy the same textual territory as the Veda, they often contain passages (called phalaśruti, “the fruits of hearing [the text]”) which list the worldly and soteriological

benefits that can accrue from hearing part of the text in recital. In many cases, these “fruits” are assured to the listeners regardless of whether or not they understand the verses in question, and irrespective of their own personal religious allegiance. In other words, according to the authors of these passages,

it is the very sounds of the Purāṇas that are sacred, and in these contexts, as with the Vedas, sound has primacy over content. In addition,

the Purāṇas also offer some of the earliest examples, within a Hindu context, of the idea of the holiness of manuscripts. Many Purāṇas list the soteriological benefits that accrue from copying manuscripts of one or other Purāṇa, from keeping, displaying and worshipping a Purāṇic manuscript in one’s house or temple (in which cases all members of the household or temple are eligible to receive benefits), and from passing such a manuscript on to others. In these cases, then, the written form of a Purāṇa functions in a similar way to its sonic form: to use Watts’s (2006) terminology, in these instances the ritualisation of the performative and iconic dimensions of Purāṇic scripture takes precedence over the ritualisation of its semantic dimension.

On the other hand, the content of the Purāṇas has a much more important place in the Hindu imagination than has, for example, the content of the Vedas. A great many of South Asia’s most popular stories of gods, sages and demons, known to millions of Hindus and retold today in multiple media, are found in the Purāṇas.

Especially important in this regard is the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, composed in South India in the 9th- 10th century CE. This work, which remains the most studied and translated of all Purāṇas, and which has inspired a large body of commentarial literature, is a central religious text for the Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava tradition, founded in 16th century Bengal.

The main focus of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa is the adoration of Kṛṣṇa as the supreme god, and it tells numerous stories of Kṛṣṇa’s exploits, including his romantic adventures with the cowherd girls in its famous tenth chapter, which would already be known to its intended audience (Narayana Rao 2004). For worshippers of Kṛṣṇa, including Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇavas,

the Bhāgavata Purāṇa is recited, listened to and read, therefore, not in order to impart or acquire information about Kṛṣṇa, but as means of celebrating and expressing devotion to him.Tantra, Āgama and StotraFrom around the 5th or 6th century CE, certain sectarian theistic traditions in North India began producing scriptural works, commonly bearing the suffixes tantra (“ritual system”) or āgama (“that which has come down”), which often present themselves as constituting a higher and more specialised revelation than that presented by the Veda.16

Within the Hindu context, the majority of these texts claim to have been authored by either Śiva or Viṣṇu, and the followers of such Tantras or Āgamas are called, respectively, Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava. There are several distinct Śaiva and Vaiṣṇava Tantric traditions, and these are primarily distinguished from one another by the mantras they use in rituals, and by their scriptural canons. The contents of

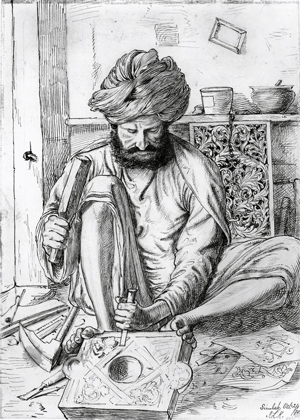

Tantric texts are predominantly liturgical: many are primarily intended as manuals for the Tantric preceptor carrying out the initiation rites (by which one becomes a member of the tradition) and the preparation for and performance of the post-initiatory worship of a range of deities.17 This worship may take place in a temple or in private.

The texts also list the rewards, including supernatural powers and liberation from worldly existence, that accrue from undergoing initiation and worshipping god or gods in the ways prescribed. However, these texts are not merely “manuals” for the preceptor, they also address various theological and cosmological topics, and many of them consist of parts apparently intended for the initiate alongside the parts intended for the preceptor. Not only is

access to these texts prohibited to the uninitiated, even for those who have undergone initiation access would be mediated by one’s preceptor or guru.

Some texts declare that they are to be read only with a guru, and that it is a sin to read them otherwise, and

some use deliberately obscure language and references in an apparent attempt to obstruct “outsiders” from accessing their content.18 For such reasons, the Tantras are

often described as being “esoteric”, in contrast to Itihāsa and the Purāṇas which are, are at least theoretically, available to everyone, including those who follow the Tantras. Tantric texts, and the practices they enjoin, are exclusive only insofar as they are the exclusive preserve of those who have been initiated into the tradition: they do not make exclusive demands on their followers, who are allowed, and in many cases encouraged, to practice the more mainstream Purāṇic rituals as well as those of the Tantras.

The Tantras and Āgamas also have much in common with the Purāṇas and, like the Purāṇas, they frequently list the soteriological and worldly benefits that ensue from hearing a particular text being recited, or from worshipping the manuscript of this or that text.

One Vaiṣṇava Tantra from the 12th or 13th century even declares that, for a member of that tradition, it is enough to recite the names of the Tantras of that tradition to ensure that one will be liberated from rebirth at death. Many works instruct initiates to worship the text by which they received initiation, and to safeguard it from falling into the wrong hands. The importance of texts for Tantric traditions is conveyed by the fact that in this context the term tantra can mean both “text” and “tradition”: perhaps more than any other Hindu traditions,

Tantric traditions are “religions of the book”. Many of these works also present themselves as being actual physical manifestations of god, so that in reading, reciting or worshipping the text the adept is directly worshipping god.The genre of Stotra (“Hymn of Praise”) shares several features with the Tantras and Āgamas. There are innumerable texts of this type, composed in many South Asian languages, and they are still being composed and published to this day.

Stotras are mostly short works in verse which directly address a deity, offering praise and seeking favours of a salvific or “worldly” nature. Many Stotras are contained within larger works (including the Yajurveda, the epics, the Purāṇas and the Tantras or Āgamas), though they have often been used independently, and many Stotras constitute independent texts in themselves. Śiva and Viṣṇu are the most commonly addressed deities alongside the goddess.

Stotras are often sung in temples during worship (pūjā), where they can function both as devotional hymns, understood as “offerings” to the divine addressee, and as liturgical texts accompanying the performance of certain rites. It is commonly understood that the recitation of such hymns, seen as an act of worship in itself, automatically brings benefits to the reciter. Unlike the Tantras or Āgamas, Stotras are not the exclusive preserve of certain sects, and many are used across sectarian boundaries.

Some Stotras consist entirely of the different names by which the god to whom they are addressed is known. Several of the most popular of these Nāmastotras (“Hymns of Praise of [God’s] Names”) are addressed to Rāma (or Rām in the now more commonly used Hindi).

Sacred Texts in Vernacular LanguagesRelative to the large body of scholarship on Sanskrit literature,

the study of the sacred vernacular literatures of South Asia is still in its infancy, with the majority of texts still in need of critical editions. A consequence of this is that general

overviews of Hinduism and its sacred literature have tended to underestimate, or else completely ignore, the important role of vernacular texts and traditions. To cite just one example, Everyman’s Library’s Hindu Scriptures has, over the course of three editions (1938, 1966, 1996) and three different editors, included, in part or whole, 19 texts, all of them in Sanskrit. And yet, in terms of the sheer numbers of Hindus who have identified, utilised and responded to sacred literature,

sacred texts in verncaular languages have enjoyed a much more prominent position over the past millennium (“the vernacular millennium” in the words of Pollock 2006) than have any Sanskrit works which, for social and linguistic reasons, are accessible only to a minority. It is commonly said that Sanskrit is the sacred language of Hinduism, yet this claim obscures the fact that many vernacular languages have also been regarded as sacred, and many vernacular texts considered, by their followers, equal in authority to the Veda.The relations between Sanskrit and vernacular, and between the Veda and vernacular sacred texts, is often addressed directly by the latter. The South Asian vernacular language with the longest literary history (approximately 2000 years) is Tamil, and

it is in Tamil literature, between the c. 10th and 12th centuries CE, that we first find vernacular texts referred to as Veda and declared superior to the Sanskrit Veda since they are available to everyone regardless of social class. Perhaps the most important Tamil text equated with the Veda is a large collection of devotional (bhakti) poems addressed to Viṣṇu, the Nālāyira Divyaprabandham (“The Divine Collection of 4000 [Verses]”), compiled around the 10th century CE by Nāthamuni, the alleged founder of the still-living Śrīvaiṣṇava tradition. The Śrīvaiṣṇavas call this text the “Tamil Veda”, and from around the 12th century, they have recited sections from it alongside sections from the Sanskrit Vedas during temple worship, at weddings and funerals, and during daily worship at home. The poems in this collection are thought to have been revealed by Viṣṇu through the 12 Āḻvār poets (c. 7th-9th centuries CE), all of whom are worshipped as saints, in the form of icons, in Śrīvaiṣṇava temples. The most sacred among the poems collected in the Nālāyira Divyaprabandham is the 1000 verse Tiruvāymoli of Nammāḻvār, a poet belonging to a peasant caste who lived in the c. 9th century CE. The Tiruvāymoli is thought by Śrīvaiṣṇavas to contain the essence of the Sāmaveda. Among the other Āḻvār poets, the most notable and arguably the most popular, is Āṇṭāḷ, the only female Āḻvār. There exists a comparable collection of Śaiva bhakti poetry in Tamil, composed from the c. 6th-10th centuries by the 63 Nāyaṇār saints, and collated in the 11th century Tirumurai, later to form part of the scriptural corpus of the Tamil Śaiva Siddhānta, a distinctive bhakti-oriented school of a pan-Indian Tantric tradition. In the following century

the poet Cekkilār composed the Periyappurāṇam, a hagiography of the Nāyaṇār saints that was revered as the “fifth Veda”, and eventually incorporated into the Tirumurai.

The second longest literary history among the Dravidian languages of South India belongs to Kannada, and the earliest extant sacred texts in this language are the devotional Vacanas (“Sayings”), short prose poems addressed to Śiva, composed by male and female members and forebears of the Vīraśaiva or Liṅgāyat movement from the 11th or 12th century CE onwards.

Basava, the alleged 12th century founder of this “bhakti protest movement” (Ramanujan 1973), which rejects the Veda and caste hierarchy, formulated the following oft-quoted pithy dismissal of Vedic tradition: “Parrots recite. So what?” (ibid.: 76). Other important sacred works in South Indian vernacular languages include Nannaya’s Mahābhāratamu, an 11th century retelling of the Mahābhārata in Telugu, and two versions of the Rāmāyaṇa in Malayalam: the 13th-14th century Rāmacaritam, known to have been ritually recited in northern Kerala (Freeman 2003: 462), and the 16th century Adhyātma Rāmāyaṇam, whose author Eḻuttacchan declared Malayalam the equal of Sanskrit, and his composition equal to the Veda.19 The cultural media via which such works have been transmitted and encountered are predominantly performative (ibid.: 438).

North Indian sacred literature in vernacular languages has also been primarily orally composed and performed and, as in South India, many important early works (in e.g. Assamese, Oriya and Bengali) are translations or retellings of Sanskrit texts. These include Jñāndev’s creative commentary in Marathi on the Bhagavadgītā, the Bhāvārthadīpikā or Jñāneśvarī (13th century), in which the author vows to place Marathi and Sanskrit on the same royal throne. A passage at the end of this work has become a popular prayer among Marathi speakers, and the work as a whole occupies a place in Marathi culture which is normally reserved for sacred works in Sanskrit.

North Indian vernacular literature commonly transcends traditional social hierarchies, and several low-caste and female authors enjoy a prominent status, with their texts recited as part of the liturgy in temples. Many works claim that their raison d’être is to make available sacred works in Sanskrit to the local populace, though several of these have far transcended such secondary status. Perhaps the best example here is the Rāmcaritmānas (“Lake of Rāma’s Deeds”), a 16th century retelling of the story of Rāma composed by Tulsīdās in the eastern Hindi dialect of Avadhi. The Rāmcaritmānas is experienced by most of its audience in oral or musical performance, being ritually recited (despite the fact that few modern Hindi speakers understand its archaic language) or acted out at popular festivals across northern India. However, it has also achieved widespread eminence as a written text, whether inscribed on temple walls, as an object of temple worship, or in the scores of printed editions found throughout the subcontinent.

For the majority of Hindus in North India, it remains the most popular narrative account of the life and career of Rāma, more popular than the Rāmāyaṇa itself, and it has been described by several Western observers as “the Bible of Northern India” (Lutgendorf 1991: 1).

ReferencesBrick, D. (2006) “Transforming Tradition into Texts: The Early Development of Smṛti”, Journal of Indian Philosophy 34: 287-302.

Freeman, Rich (2003) “Genre and Society. The Literary Culture of Premodern Kerala”, in Sheldon Pollock (ed.) Literary Cultures in History. Reconstructions from South Asia, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 437-500.

Goldman, Robert and Goldman, Sally Sutherland (2010) “Rāmāyaṇa”, in Knut A. Jacobsen et al. (eds.) Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Volume Two, Boston, Leiden: Brill, 111-126.

Jamison, Stephanie W. and Brereton, Joel P. (trans.) (forthcoming) The Rigveda, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lutgendorf, Philip (1991) The Life of a Text: Performing the Rāmcaritmānas of Tulsīdās, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Malinar, Angelika (2007) The Bhagavadgītā: Doctrines and Contexts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCrea, Lawrence (2011) “Mīmāṃsā”, in Knut A. Jacobsen et al. (eds.) Brill’s Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Volume Three, Leiden, Boston: Brill, 643-656.

Narayana Rao, Velcheru (2004) “Purāṇa”, in Sushil Mittal and Gene Thursby (eds.) The Hindu World, New York, NY: Routledge, 97-118.

Olivelle, Patrick (trans.) (2004) The Law Code of Manu, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Olivelle, Patrick (2010) “Dharmaśāstra: a textual history”, in Timothy Lubin, Donald R. Davis Jr., and Jayanth K. Krishnan (eds.) Hinduism and Law: An Introduction, New York: Cambridge University Press, 28-57.

Pollock, Sheldon (1997) “The ‘Revelation’ of ‘Tradition’: Śruti, Smṛti, and the Sanskrit Discourse of Power”, in S. Lienhard and I. Piovano (eds.) Lex et Litterae: Studies in Honour of Professor Oscar Botto, Alessandria: Edizioni dell’Orzo, 395- 417.

Pollock, Sheldon (2006) The Language of the Gods in the World of Men. Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India, Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press.

Ramanujan, A. K. (trans.) (1973) Speaking of Śiva, London: Penguin Books.

Smith, Frederick M. (1994) “Purāṇaveda”, in Laurie L. Patton (ed.) Authority, Anxiety and Canon: Essays in Vedic Interpretation, Albany: SUNY Press, 97-138.

Watts, James W. (2006) “The Three Dimensions of Scriptures”, Postscripts 2.2-3: 135-159.

Witzel, Michael (1997) “The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools: The Social and Political Milieu”, in Witzel (ed.): Inside the Texts, Beyond the Texts. New Approaches to the Study of the Vedas, Cambridge: Harvard Oriental Series, 257-345.

_______________

Notes:1 Evidence suggests that writing was introduced into the Indian subcontinent by the Persian conquerors of Gandhāra (in the extreme northwest) in the second half of the 6th century BCE. Gandhāra is the homeland of what is possibly the earliest Indic script, namely Kharoṣṭhī, which is derived from the Aramaic script. The earliest evidence for writing in Kharoṣṭhī, or indeed in any Indic script, is dateable to the reign of Aśoka (c. 269-232 BCE).

2 There is, as yet, no complete, reliable English translation of the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā, though this is set to change in 2014 with the greatly anticipated forthcoming translation of Jamison and Brereton.

3 Thus, the Sāmavedasaṃhitā consists almost entirely of verses from the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā. The ritual role of the priests associated with the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā was the simple recitation (rather than singing) of its verses.

4 Certain conservative traditions have never accepted the authority of the Atharvaveda, and recognise, therefore, only three Vedas.

5 These adaptations show that although the Ṛgvedasaṃhitā was clearly highly regarded, it was not yet sacrosanct.

6 Hence, the Upaniṣads are considered to represent “the end of the Veda” (Vedānta), and are indeed often referred to in this way.

7 However, their authors are also often considered to be “seers” (ṛṣi), and for instance Patañjali, author of a 2nd century BCE grammatical text, has, from around the 13th century, been considered an incarnation of Śeṣa, the divine grammarian.

8 However, there are references in later literature (from the c. 9th or 10th century CE) to these texts being worshipped, alongside the Vedas and other works, in their written form.

9 Popular retellings in modern times include Peter Brook’s nine hour play The Mahabharata (1985), and the hugely popular Hindi TV serials of the Ramayan (dir. Ramanand Sagar, 1987-8) and Mahabharat (dir. Ravi Chopra, 1988-90).

10 The Mahābhārata is approximately four times the length of the Bible, the Rāmāyaṇa about the same length as the latter.

11 The first translation into a European language was by Charles Wilkins into English in 1785. Subsequent important translations of the text include those by A. W. von Schlegel into Latin (1823) (which attracted the attention of G. W. F. Hegel and others), and Richard Garbe into German (1905).

12 Malinar (2007) combines both approaches.

13 There is also a smaller, albeit substantial, corpus of Jain Purāṇas, written in a variety of South Asian languages, including Sanskrit. These will not be discussed here.

14 The Purāṇas continue theistic trends observable in the later layers of the epics, with certain texts, such as the Viṣṇu Purāṇa and the Devī Māhātmya of the Mārkaṇḍeya Purāṇa clearly emphasising the sectarian worship of one particular god or goddess.

15 Accordingly, much of the scholarship on the Purāṇas has approached these texts through particular themes, concentrating on recurrent myths and modes of worship or literary style etc. rather than treating each text as an individual whole.

16 Not all Tantras and Āgamas present themselves as being superior to the Veda. For instance, the South Indian Vaikhānasa tradition, which produced a large body of scriptural literature from the c. 9th century, refers to its texts as Tantra and Āgama, but identifies itself as a Vedic school. In addition, there are Jain and Buddhist Tantras, which do not identify themselves in relation to the Veda at all.

17 There is no uniform rule as to who is eligible for Tantric initiations – particular traditions have their own criteria, which are liable to change over time. Some traditions accept only male members of the three highest social classes, others accept male and female initiates from all social classes.

18 Such strategies have, historically, affected scholarship on the Tantras. In the last 30 years or so, however, real advances have been made in this area, and today the text-critical study of the Tantras and their commentaries is one of the fastest growing areas in South Asian textual scholarship.

19 Kampaṉ’s 12th century retelling of the Rāmāyaṇa in Tamil, the Irāmāvatāram, the verses of which are inscribed on temple walls across central and southern Tamil Nadu, predates both of these.