Indraby Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/7/20

HYMN XXXIV

1 He who just born, chief God of lofty spirit, by power and might became the God's protector,

Before whose breath, through greatness of his valour, the two worlds trembled, He, O men, is Indra.

2 He who fixed fast and firm the earth that staggered, and set at rest the agitated mountains,

Who measured out air's wider middle region and gave theheaven support, He, O men, is Indra.

3 Who slew the Dragon, freed the Seven Rivers, and draye the kine forth from the cave of Vala,

Begat the fire between both stones, the spoiler in warrior's battle, He, O men, is Indra.

4 By whom this universe was made to tremble, who chased away the humbled brood of demon,

Who, like a gambler gathering his winnings, seized the foe's riches, He, O men, is Indra.

5 Of whom, the terrible, they ask, Where is He? or verily they say of him, He is not.

He wastes the foeman's wealth like stakes of gamblers. Have faith in him for He, O men, is Indra.

6 Stirrer to action of the poor and lowly, of priest, of suppliant who sings his praises

Who, fair-faced, favours him who presseth Soma with stones adjusted, He, O men, is Indra.

7 He under whose supreme control are horses, all chariots, and the hamlets, and the cattle:

He who begat the Sun, begat the Morning, leader of waters. He, O men, is Indra.

8 To whom both armies cry in close encounter, foe against foe, the stronger and the weaker;

Whom two invoke upon one chariot mounted, each for himself, He, O ye men, is Indra.

9 He, without whom men conquer not in battle, whom, warring, they invoke for help and succour;

He, all this universe's type and image, who shakes what never shook, He, men, is Indra.

10 He who hath smitten, ere they know their danger, with his hurled weapon many grievous sinners:

Who pardons not his boldness who provokes him, who slays the Dasyu, He, O men, is Indra.

11 He who discovered in the fortieth autumn Sambara dwelling in the midst of mountains:

Who slew the Dragon putting forth his vigour, the demon lying there, He, men, is Indra.

12 Who drank the juice poured at the seas of Order, subduing Sambara by superior prowess,

Who hoarded food within the mountain's hollow wherein he grew in strength, He, men, is Indra.

13 Who, with seven guiding reins, the Bull, the mighty, set the Seven Rivers free to flow at pleasure;

Who, thunder-armed, rent Rauhina in pieces when scaling heaven, He, O ye men, is Indra.

14 Heaven, even, and the earth bow down before him, before his very breath the mountains tremble.

Known as the Soma-drinker, armed with thunder, the wielder of the bolt, He, men, is Indra.

15 Who aids with favour him who pours the Soma, and him who brews it, sacrificer, singer;

Whose strength our prayer and offered Soma heighten, and this our gift, He, O ye men, is Indra.

16 Born, manifested in his Parents' bosom, He knoweth as a son the Highest Father.

He who with vigorous energy assisted the companies of Gods, He, men, is Indra

17 Lord of Bay steeds, who loves the flowing Soma, He before whom all living creatures tremble.

He who smote Sambara and slaughtered Sushna, He the Sole Hero, He, O men, is Indra.

18 Thou verily art true strong God who sendest wealth to the man who brews and pours libation.

So may we evermore, thy friends, O Indra, address the synod with brave sons about us.

-- The Hymns of the Atharvaveda, translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith

Indra, King of the Gods, God of Lightning, Thunder, Rains and River flows, Ruler of Heaven

Indra, Parjanya

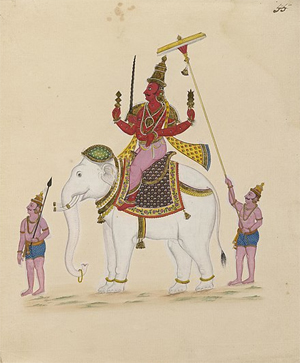

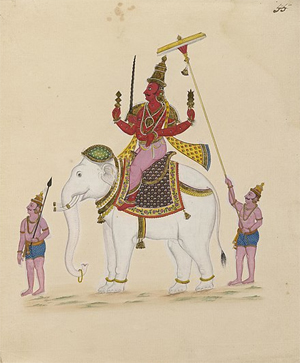

Painting of Indra on his elephant mount, Airavata.

Devanagari इन्द्र or इंद्र

Sanskrit transliteration Īndra

Affiliation: Deva (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism)

Abode: Amarāvati, the capital of Indraloka (Indra's world) in Svarga,[1] Trāyastriṃśa (Heaven of the 33), Mount Meru

Weapon: Vajra (Thunderbolt), Astras, Vasavi Shakthi

Symbols: Vajra, Indra's net

Mount: Airavata (White elephant), Uchchaihshravas (White horse)

Texts: Vedas, Puranas, Jātakas, Epics

Personal information

Parents: Kashyapa and Aditi

Consort: Shachi

Children: Jayanta, Jayanti, Devasena, Vali and Arjuna

Equivalents

Greek equivalent: Zeus

Roman equivalent: Jupiter

Norse equivalent: Thor

Slavic equivalent: Perun

Indra (/ˈɪndrə/; Sanskrit: इन्द्र) is an ancient Vedic deity in Hinduism,[2] a guardian deity (Indā[3] in Pali) in Buddhism,[4] and the king of the highest heaven called Saudharmakalpa in Jainism.[5] He is also an important deity worshipped in Kalasha religion, indicating his prominence in ancient Hinduism.[6][7][8][9][10] [11] [12] Indra's mythology and powers are similar to other Indo-European deities such as Jupiter, Perun, Perkūnas, Zalmoxis, Taranis, Zeus, and Thor, suggesting a common orgin in Proto-Indo-European mythology.[2][13][14]

In the Vedas, Indra is the king of Svarga (Heaven) along with his capital city Amaravati and the Devas. He is the deity of the heavens, lightning, thunder, storms, rains, river flows, and war.[15][16][17] Indra is the most referred to deity in the Rigveda.[18] He is celebrated for his powers, and the one who kills the great symbolic evil (malevolent type of Asura) named Vritra who obstructs human prosperity and happiness. Indra destroys Vritra and his "deceiving forces", and thereby brings rains and the sunshine as the friend of mankind.[2][19] His importance diminishes in the post-Vedic Indian literature where he is depicted as a powerful hero but one who constantly gets into trouble with his drunken, hedonistic and adulterous ways, and the god who disturbs Hindu monks as they meditate because he fears self-realized human beings may become more powerful than him.[2][20]

Indra rules over the much-sought Devas realm of rebirth within the Samsara doctrine of Buddhist traditions.[21] However, like the Hindu texts, Indra also is a subject of ridicule and reduced to a figurehead status in Buddhist texts,[22] shown as a god that suffers rebirth and redeath.[21] In the Jainism traditions, unlike Buddhism and Hinduism, Indra is not the king of Gods- the enlightened leaders (called Tirthankaras or Jinas), but King of superhumans residing in Swarga-Loka, and very much a part of Jain rebirth cosmology.[23] He is also the one who appears with his wife Indrani to celebrate the auspicious moments in the life of a Jain Tirthankara, an iconography that suggests the king and queen of superhumans residing in Swarga (heaven) reverentially marking the spiritual journey of a Jina.[24][25]

Indra's iconography shows him wielding a lightning thunderbolt weapon known as Vajra, riding on a white elephant known as Airavata.[20][26] In Buddhist iconography the elephant sometimes features three heads, while Jaina icons sometimes show the elephant with five heads. Sometimes a single elephant is shown with four symbolic tusks.[20] Indra's heavenly home is on or near Mount Meru (also called Sumeru).[21][27]

Etymology and nomenclature Indra on his elephant, guarding the entrance of the 1st century BCE Buddhist Cave 19 at Bhaja Caves (Maharashtra).[28]

Indra on his elephant, guarding the entrance of the 1st century BCE Buddhist Cave 19 at Bhaja Caves (Maharashtra).[28] Buddhist relief from Loriyan Tangai, showing Indra paying homage to the Buddha at the Indrasala Cave, 2nd century CE, Gandhara

Buddhist relief from Loriyan Tangai, showing Indra paying homage to the Buddha at the Indrasala Cave, 2nd century CE, Gandhara The etymological roots of Indra are unclear, and it has been a contested topic among scholars since the 19th-century, one with many proposals.[29][30] The significant proposals have been:

• root ind-u, or "rain drop", based on the Vedic mythology that he conquered rain and brought it down to earth.[20][29]

• root ind, or "equipped with great power". This was proposed by Vopadeva.[20]

• root idh or "kindle", and ina or "strong".[31][32]

• root indha, or "igniter", for his ability to bring light and power (indriya) that ignites the vital forces of life (prana). This is based on Shatapatha Brahmana.[33]

• root idam-dra, or "It seeing" which is a reference to the one who first perceived the self-sufficient metaphysical Brahman. This is based on Aitareya Upanishad.[20]

• roots in ancient Indo-European, Indo-Aryan deities.[34] For example, states John Colarusso, as a reflex of proto-Indo-European *h₂nḗr-, Greek anēr, Sabine nerō, Avestan nar-, Umbrian nerus, Old Irish nert, Ossetic nart, and others which all refer to "most manly" or "hero".[34]

Colonial era scholarship proposed that Indra shares etymological roots with Zend Andra, Old High German Antra, or Jedru of Old Slavonic, but Max Muller critiqued these proposals as untenable.[29][35] Later scholarship has linked Vedic Indra to Aynar (the Great One) of Circassian, Abaza and Ubykh mythology, and Innara of Hittite mythology.[34][36] Colarusso suggests a Pontic[note 1] origin and that both the phonology and the context of Indra in Indian religions is best explained from Indo-Aryan roots and a Circassian etymology (i.e. *inra).[34]

Other languagesFor other languages, he is also known as

• Bengali: ইন্দ্র (Indro)

• Burmese: သိကြားမင်း (pronounced [ðadʑá mɪ́ɰ̃])

• Chinese: 帝释天 (Dìshìtiān)

• Indonesian/Malay: (Indera)

• Japanese: 帝釈天 (Taishakuten).[37]

• Javanese: ꦧꦛꦫꦲꦶꦤ꧀ꦢꦿ (Bathara Indra)

• Kannada: ಇಂದ್ರ (Indra)

• Khmer: ព្រះឥន្ទ្រ (ព្រះឥន្ទ) (pronounced [preah ʔən])

• Lao: ພະອິນ (Pha In) or ພະຍາອິນ (Pha Nya In)

• Malayalam: ഇന്ദ്രൻ (Indran)

• Mon: ဣန် (In)

• Odia:ଇନ୍ଦ୍ର(Indraw)

• Tai Lue: ᦀᦲᧃ (In) or ᦘᦍᦱᦀᦲᧃ (Pha Ya In)

• Tamil: இந்திரன் (Inthiran)

• Telugu: ఇంద్రుడు (Indrudu or Indra)

• Thai: พระอินทร์ (Phra In)

Indra has many epithets in the Indian religions, notably Śakra (शक्र, powerful one), Vṛṣan (वृषन्, mighty), Vṛtrahan (वृत्रहन्, slayer of Vṛtra), Meghavāhana (मेघवाहन, he whose vehicle is cloud), Devarāja (देवराज, king of deities), Devendra (देवेन्द्र, the lord of deities),[38] Surendra (सुरेन्द्र, chief of deities), Svargapati (स्वर्गपति, the lord of heaven), Vajrapāṇī (वज्रपाणि, he who has thunderbolt (Vajra) in his hand) and Vāsava (वासव, lord of Vasus).

Origins Banteay Srei temple's pediment carvings depict Indra mounts on Airavata, Cambodia.

Banteay Srei temple's pediment carvings depict Indra mounts on Airavata, Cambodia.Indra is of ancient but unclear origin. Aspects of Indra as a deity are cognate to other Indo-European gods; they are thunder gods such as Thor, Perun, and Zeus who share parts of his heroic mythologies, act as king of gods, and all are linked to "rain and thunder".[39] The similarities between Indra of Vedic mythologies and of Thor of Nordic and Germanic mythologies are significant, states Max Muller. Both Indra and Thor are storm gods, with powers over lightning and thunder, both carry a hammer or an equivalent, for both the weapon returns to their hand after they hurl it, both are associated with bulls in the earliest layer of respective texts, both use thunder as a battle-cry, both are protectors of mankind, both are described with legends about "milking the cloud-cows", both are benevolent giants, gods of strength, of life, of marriage and the healing gods.[40]

Michael Janda suggests that Indra has origins in the Indo-European *trigw-welumos [or rather *trigw-t-welumos] "smasher of the enclosure" (of Vritra, Vala) and diye-snūtyos "impeller of streams" (the liberated rivers, corresponding to Vedic apam ajas "agitator of the waters").[41] Brave and heroic Innara or Inra, which sounds like Indra, is mentioned among the gods of the Mitanni, a Hurrian-speaking people of Hittite region.[42]

Indra as a deity had a presence in northeastern Asia minor, as evidenced by the inscriptions on the Boghaz-köi clay tablets dated to about 1400 BCE. This tablet mentions a treaty, but its significance is in four names it includes reverentially as Mi-it-ra, U-ru-w-na, In-da-ra and Na-sa-at-ti-ia. These are respectively, Mitra, Varuna, Indra and Nasatya-Asvin of the Vedic pantheon as revered deities, and these are also found in Avestan pantheon but with Indra and Naonhaitya as demons. This at least suggests that Indra and his fellow deities were in vogue in South Asia and Asia minor by about mid 2nd-millennium BCE.[31][43]

Indra is praised as the highest god in 250 hymns of the Rigveda – a Hindu scripture dated to have been composed sometime between 1700 and 1100 BCE. He is co-praised as the supreme in another 50 hymns, thus making him one of the most celebrated Vedic deities.[31] He is also mentioned in ancient Indo-Iranian literature, but with a major inconsistency when contrasted with the Vedas. In the Vedic literature, Indra is a heroic god. In the Avestan (ancient, pre-Islamic Iranian) texts such as Vd. 10.9, Dk. 9.3 and Gbd 27.6-34.27, Indra – or accurately Andra[44] – is a gigantic demon who opposes truth.[34][note 2] In the Vedic texts, Indra kills the archenemy and demon Vritra who threatens mankind. In the Avestan texts, Vritra is not found.[44]

Indra is called vr̥tragʰná- (literally, "slayer of obstacles") in the Vedas, which corresponds to Verethragna of the Zoroastrian noun verethragna-. According to David Anthony, the Old Indic religion probably emerged among Indo-European immigrants in the contact zone between the Zeravshan River (present-day Uzbekistan) and (present-day) Iran.[45] It was "a syncretic mixture of old Central Asian and new Indo-European elements",[45] which borrowed "distinctive religious beliefs and practices"[46] from the Bactria–Margiana Culture.[46] At least 383 non-Indo-European words were found in this culture, including the god Indra and the ritual drink Soma.[47] According to Anthony,

Many of the qualities of Indo-Iranian god of might/victory, Verethraghna, were transferred to the god Indra, who became the central deity of the developing Old Indic culture. Indra was the subject of 250 hymns, a quarter of the Rig Veda. He was associated more than any other deity with Soma, a stimulant drug (perhaps derived from Ephedra) probably borrowed from the BMAC religion. His rise to prominence was a peculiar trait of the Old Indic speakers.[48]

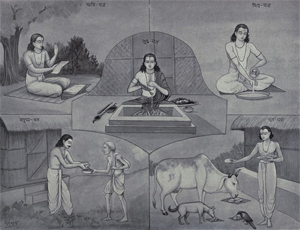

Hinduism Indra is typically featured as a guardian deity on the east side of a Hindu temple.

Indra is typically featured as a guardian deity on the east side of a Hindu temple.Indra was a prominent deity in the Vedic era of Hinduism.[31]

Vedic textsOver a quarter of the 1,028 hymns of the Rigveda mention Indra, making him the most referred to deity than any other.[31][49] These hymns present a complex picture of Indra, but some aspects of Indra are oft repeated. Of these, the most common theme is where he as the god with thunderbolt kills the evil serpent Vritra that held back rains, and thus released rains and land nourishing rivers.[29] For example, the Rigvedic hymn 1.32 dedicated to Indra reads:

इन्द्रस्य नु वीर्याणि प्र वोचं यानि चकार प्रथमानि वज्री ।

अहन्नहिमन्वपस्ततर्द प्र वक्षणा अभिनत्पर्वतानाम् ॥१।।

अहन्नहिं पर्वते शिश्रियाणं त्वष्टास्मै वज्रं स्वर्यं ततक्ष ।

वाश्रा इव धेनवः स्यन्दमाना अञ्जः समुद्रमव जग्मुरापः ॥२।।

1. Now I shall proclaim the heroic deeds of Indra, those foremost deeds that the mace-wielder performed:

He smashed the serpent. He bored out the waters. He split the bellies of the mountains.

2. He smashed the serpent resting on the mountain—for him Tvaṣṭar had fashioned the resounding [sunlike] mace.

Like bellowing milk-cows, streaming out, the waters went straight down to the sea. [50]

—Rigveda, 1.32.1–2[51]

The hymns of Rigveda declare him to be the "king that moves and moves not", the friend of mankind who holds the different tribes on earth together.[52] In one interpretation by Oldenberg, the hymns are referring to the snaking thunderstorm clouds that gather with bellowing winds (Vritra), Indra is then seen as the storm god who intervenes in these clouds with his thunderbolts, which then release the rains nourishing the parched land, crops and thus humanity.[53] In another interpretation by Hillebrandt, Indra is a symbolic sun god (Surya) and Vritra is a symbolic winter-giant (historic mini cycles of ice age, cold) in the earliest, not the later, hymns of Rigveda. The Vritra is an ice-demon of colder central Asia and northern latitudes, who holds back the water. Indra is the one who releases the water from the winter demon, an idea that later metamorphosed into his role as storm god.[53] According to Griswold, this is not a completely convincing interpretation, because Indra is simultaneously a lightning god, a rain god and a river-helping god in the Vedas. Further, the Vritra demon that Indra slew is best understood as any obstruction, whether it be clouds that refuse to release rain or mountains or snow that hold back the water.[53]

Even though Indra is declared as the king of gods in some verses, there is no consistent subordination of other gods to Indra. In Vedic thought, all gods and goddesses are equivalent and aspects of the same eternal abstract Brahman, none consistently superior, none consistently inferior. All gods obey Indra, but all gods also obey Varuna, Vishnu, Rudra and others when the situation arises. Further, Indra also accepts and follows the instructions of Savitr (solar deity).[54] Indra, like all Vedic deities, is a part of henotheistic theology of ancient India.[55]

Indra is not a visible object of nature in the Vedic texts, nor is he a personification of any object, but that agent which causes the lightning, the rains and the rivers to flow.[56] His myths and adventures in the Vedic literature are numerous, ranging from harnessing the rains, cutting through mountains to help rivers flow, helping land becoming fertile, unleashing sun by defeating the clouds, warming the land by overcoming the winter forces, winning the light and dawn for mankind, putting milk in the cows, rejuvenating the immobile into something mobile and prosperous, and in general, he is depicted as removing any and all sorts of obstacles to human progress.[57] The Vedic prayers to Indra, states Jan Gonda, generally ask "produce success of this rite, throw down those who hate the materialized Brahman".[58]

Indra is often presented as the twin brother of Agni (fire) – another major Vedic deity.[59] Yet, he is also presented to be the same, states Max Muller, as in Rigvedic hymn 2.1.3, which states, "Thou Agni, art Indra, a bull among all beings; thou art the wide-ruling Vishnu, worthy of adoration. Thou art the Brahman, (...)."[60] He is also part of one of many Vedic trinities as "Agni, Indra and Surya", representing the "creator-maintainer-destroyer" aspects of existence in Hindu thought.[49][note 3]

Rigveda 2.1.3 Jamison 2014 [64]

You, Agni, as bull of beings, are Indra; you, wide-going, worthy of homage, are Viṣṇu. You, o lord of the sacred formulation, finder of wealth, are the Brahman [Formulator]; you, o Apportioner, are accompanied by Plenitude.

UpanishadsThe ancient Aitareya Upanishad equates Indra, along with other deities, with Atman (soul, self) in the Vedanta's spirit of internalization of rituals and gods. It begins with its cosmological theory in verse 1.1.1 by stating that, "in the beginning, Atman, verily one only, was here - no other blinking thing whatever; he bethought himself: let me now create worlds".[65][66] This soul, which the text refers to as Brahman as well, then proceeds to create the worlds and beings in those worlds wherein all Vedic gods and goddesses such as sun-god, moon-god, Agni and other divinities become active cooperative organs of the body.[66][67][68] The Atman thereafter creates food, and thus emerges a sustainable non-sentient universe, according to the Upanishad. The eternal Atman then enters each living being making the universe full of sentient beings, but these living beings fail to perceive their Atman. The first one to see the Atman as Brahman, asserts the Upanishad, said, "idam adarsha or "I have seen It".[66] Others then called this first seer as Idam-dra or "It-seeing", which over time came to be cryptically known as "Indra", because, claims Aitareya Upanishad, everyone including the gods like short nicknames.[69] The passing mention of Indra in this Upanishad, states Alain Daniélou, is a symbolic folk etymology.[20]

The section 3.9 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad connects Indra to thunder, thunderbolt and release of waters.[70] In section 5.1 of the Avyakta Upanishad, Indra is praised as he who embodies the qualities of all gods.[49]

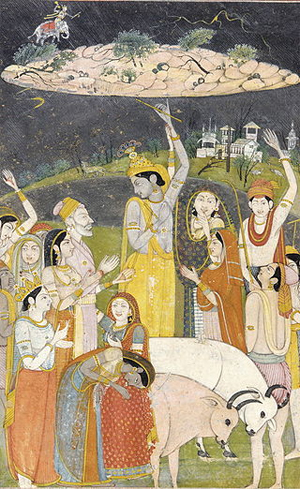

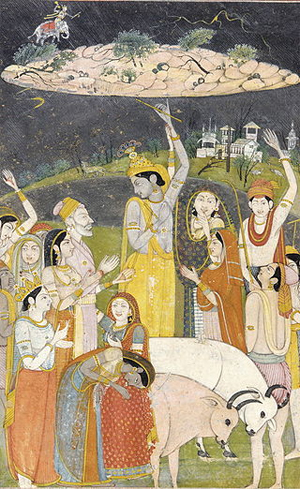

Post-Vedic texts Krishna holding Govardhan hill from Smithsonian Institution’s collections

Krishna holding Govardhan hill from Smithsonian Institution’s collectionsIn post-Vedic texts, Indra is depicted as an intoxicated hedonistic god, his importance declines, and he evolves into a minor deity in comparison to others in the Hindu pantheon, such as Shiva, Vishnu, or Devi. In Hindu texts, Indra is some times known as an aspect (avatar) of Shiva.[49]

He is depicted as the father of Vali in the Ramayana and Arjuna in the Mahabharata.[22]Since he is known for mastering over all weapons in warfare, his spiritual sons Vali and Arjuna are also very good in warfare. He becomes a source of nuisance rains in the Puranas, out of anger and with an intent to hurt mankind. But, Krishna as an avatar of Vishnu, comes to the rescue by lifting Mount Govardhana on his fingertip, and letting mankind shelter under the mountain till Indra exhausts his anger and relents.[22] Also, according to Mahabharata Indra, disguised himself as a Brahmin approached Karna and asked for his kavach (body armor) and kundal (earrings) as charity. Although being aware of his true identity, Karna peeled off his kavach and kundal and fulfilled the wish of Indra. Pleased by this act Indra, gifted Karna a dart called Vasavi Shakthi.

Sangam literature (300 BCE–300 AD)Sangam literature of the Tamil language contains more stories about Indra by various authors. In Silapathikaram Indra is described as Maalai venkudai mannavan (மாலைவெண் குடை மன்னவன்), literally meaning Indra with the pearl-garland and white umbrella.[71]

The Sangam literature also describes Indhira Vizha (festival for Indra), the festival for want of rain, celebrated for one full month starting from the full moon in Ootrai (later name – Cittirai) and completed on the full moon in Puyaazhi (Vaikaasi) (which coincides with Buddhapurnima). It is described in the epic Cilapatikaram in detail.[72]

Relations with other godsIn the Hindu religion, he is married to Shachi, also known as Indrani or Pulomaja.[73]

Indra and Shachi have two sons: Chitragupta and Jayanta; and two daughters: Jayanti and Devasena. Goddess Jayanti is the spouse of Shukra, while Goddess Devasena marries the war-god Kartikeya.[74]

MythologyIn the Brahmavaivarta Purana,[75] Indra defeats Vritra and releases the waters. Indra asks Vishvakarma to build him a palace, but ultimately decides to leave his life of luxury to become a hermit and seek wisdom. Horrified, Indra's wife Shachi asks the priest Brihaspati to change her husband's mind. He teaches Indra to see the virtues of both the spiritual life and the worldly life. Thus, at the end of the story, Indra learns how to pursue wisdom while still fulfilling his kingly duties.[citation needed]

Iconography

Indra's iconography shows him holding a thunderbolt or Vajra and a sword. In addition he is shown on top of his elephant Airavata, which reinforces his characteristic of King of the Gods.

Indra's iconography shows him holding a thunderbolt or Vajra and a sword. In addition he is shown on top of his elephant Airavata, which reinforces his characteristic of King of the Gods.In Rigveda, Indra is described as strong willed, armed with a thunderbolt, riding a chariot:

5. Let bullish heaven strengthen you, the bull; as bull you travel with your two bullish fallow bays. As bull with a bullish chariot, well-lipped one, as bull with bullish will, you of the mace, set us up in loot.

— Rigveda, Book 5, Hymn 37: Jamison[76]

Indra's weapon, which he used to kill evil Vritra, is the Vajra or thunderbolt. Other alternate iconographic symbolism for him includes a bow (sometimes as a colorful rainbow), a sword, a net, a noose, a hook, or a conch.[77] The thunderbolt of Indra is called Bhaudhara.[78]

In the post-Vedic period, he rides a large, four-tusked white elephant called Airavata.[20] In sculpture and relief artworks in temples, he typically sits on an elephant or is near one. When he is shown to have two, he holds the Vajra and a bow.[79]

In the Shatapatha Brahmana and in Shaktism traditions, Indra is stated to be same as goddess Shodashi (Tripura Sundari), and her iconography is described similar to those of Indra.[80]

The rainbow is called Indra's Bow (Sanskrit: indradhanus इन्द्रधनुस्).[77]

BuddhismThe Buddhist cosmology places Indra above Mount Sumeru, in Trayastrimsha heaven.[4] He resides and rules over one of the six realms of rebirth, the Devas realm of Saṃsāra, that is widely sought in the Buddhist tradition.[81][note 4] Rebirth in the realm of Indra is a consequence of very good Karma (Pali: kamma) and accumulated merit during a human life.[84]

In Buddhism, Indra is commonly called by his other name, Śakra or Sakka, ruler of the Trāyastriṃśa heaven.[85] Śakra is sometimes referred to as Devānām Indra or "Lord of the Devas". Buddhist texts also refer to Indra by numerous names and epithets, as is the case with Hindu and Jain texts. For example, Asvaghosha's Buddhacarita in different sections refers to Indra with terms such as "the thousand eyed",[86] Puramdara,[87] Lekharshabha,[88] Mahendra, Marutvat, Valabhid and Maghavat.[89] Elsewhere, he is known as Devarajan (literally, "the king of gods"). These names reflect a large overlap between Hinduism and Buddhism, and the adoption of many Vedic terminology and concepts into Buddhist thought.[90] Even the term Śakra, which means "mighty", appears in the Vedic texts such as in hymn 5.34 of the Rigveda.[20][91]

In Theravada Buddhism Indra is referred to as Indā in Evening Chanting such as the Udissanādiṭṭhānagāthā (Iminā).[92]

The Buddha (middle) is flanked by Brahma (left) and Indra, possibly the oldest surviving Buddhist artwork.[93]

The Buddha (middle) is flanked by Brahma (left) and Indra, possibly the oldest surviving Buddhist artwork.[93]The Bimaran Casket made of gold inset with garnet, dated to be around 60 CE, but some proposals dating it to the 1st century BCE, is among the earliest archaeological evidences available that establish the importance of Indra in Buddhist mythology. The artwork shows the Buddha flanked by gods Brahma and Indra.[93][94]

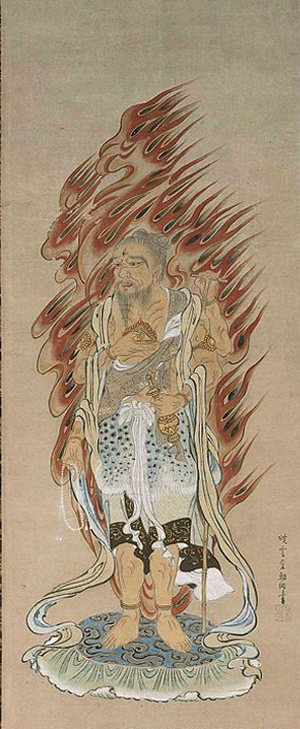

In China, Korea, and Japan, he is known by the characters 帝釋天 (Chinese: 釋提桓因, pinyin: shì dī huán yīn, Korean: "Je-seok-cheon" or 桓因 Hwan-in, Japanese: "Tai-shaku-ten", kanji: 帝釈天). In Japan, Indra always appears opposite Brahma (梵天, Japanese: "Bonten") in Buddhist art. Brahma and Indra are revered together as protectors of the historical Buddha (Chinese: 釋迦, kanji: 釈迦, also known as Shakyamuni), and are frequently shown giving the infant Buddha his first bath. Although Indra is often depicted like a bodhisattva in the Far East, typically in Tang dynasty costume, his iconography also includes a martial aspect, wielding a thunderbolt from atop his elephant mount.[citation needed]

Many official seals in southeast Asia feature Indra.[95] Above: seal of Bangkok, Thailand.

Many official seals in southeast Asia feature Indra.[95] Above: seal of Bangkok, Thailand.In some schools of Buddhism and in Hinduism, the image of Indra's net is a metaphor for the emptiness of all things, and at the same time a metaphor for the understanding of the universe as a web of connections and interdependences[96][circular reference].

In Japan, Indra is one of the twelve Devas, as guardian deities, who are found in or around Buddhist temples (Jūni-ten, 十二天).[97] In Japan, Indra has been called "Taishaku-ten".[98] He joins these other eleven Devas of Buddhism, found in Japan and other parts of southeast Asia: Agni (Ka-ten), Yama (Enma-ten), Nirrti (Rasetsu-ten), Vayu (Fu-ten), Ishana (Ishana-ten), Kubera (Tamon-ten), Varuna (Sui-ten), Brahma (Bon-ten), Prithvi (Chi-ten), Surya (Nit-ten), and Chandra (Gat-ten).[98][99][100]

The ceremonial name of Bangkok claims that the city was "given by Indra and built by Vishvakarman."[101]

Jainism Indra as a guardian deity sitting on elephant in Jain cave temple at Ellora

Indra as a guardian deity sitting on elephant in Jain cave temple at Ellora Indra, Indrani with elephant at the 9th-century Mirpur Jain Temple in Rajasthan (rebuilt 15th-century).

Indra, Indrani with elephant at the 9th-century Mirpur Jain Temple in Rajasthan (rebuilt 15th-century).Indra in Jain mythology always serves the Tirthankara teachers. Indra most commonly appears in stories related to Tirthankaras, in which Indra himself manages and celebrates the five auspicious events in that Tirthankara's life, such as Chavan kalyanak, Janma kalyanak, Diksha kalyanak, Kevala Jnana kalyanak, and moksha kalyanak.[102]

There are sixty-four Indras in Jaina literature, each ruling over different heavenly realms where heavenly souls who have not yet gained Kaivalya (moksha) are reborn according to Jainism.[24][103] Among these many Indras, the ruler of the first Kalpa heaven is the Indra who is known as Saudharma in Digambara, and Sakra in Śvētāmbara tradition. He is most preferred, discussed and often depicted in Jaina caves and marble temples, often with his wife Indrani.[103][104] They greet the devotee as he or she walks in, flank the entrance to an idol of Jina (conqueror), and lead the gods as they are shown celebrating the five auspicious moments in a Jina's life, including his birth.[24] These Indra-related stories are enacted by laypeople in Jainism tradition during special Puja (worship) or festive remembrances.[24][105]

In south Indian Digambara Jaina community, Indra is also the title of hereditary priests who preside over Jain temple functions.[24]

See also• Rigvedic deities

• Indreshwar

• Deva

• Nahusha

• Aditya

• Lokapala

• Dikpala

• Indraloka

• Astra

• Astra of Indrajit

• Indra Dhwaja

• Indrajāla

• Vajra, also Bhaudhara

• Vijaya Dhanush

• Trāyastriṃśa

• Nat

• Ten-bu

• Dharmapala

• Sakra or Sakka

• Indranama

• Saman

• Taishakuten

• Thagyamin

• Vajrapani

• Yuanshi Tianzun

• Jade Emperor

• Hwanin

• Tengri

Notes1. near Black Sea.

2. In deities that are similar to Indra in the Hittite and European mythologies, he is also heroic.[34]

3. The Trimurti idea of Hinduism, states Jan Gonda, "seems to have developed from ancient cosmological and ritualistic speculations about the triple character of an individual god, in the first place of Agni, whose births are three or threefold, and who is threefold light, has three bodies and three stations".[61] Other trinities, beyond the more common "Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva", mentioned in ancient and medieval Hindu texts include: "Indra, Vishnu, Brahmanaspati", "Agni, Indra, Surya", "Agni, Vayu, Aditya", "Mahalakshmi, Mahasarasvati, and Mahakali", and others.[62][63]

4. Scholars[82][83] note that better rebirth, not nirvana, has been the primary focus of a vast majority of lay Buddhists. This is sought in the Buddhist traditions through merit accumulation and good kamma.

References1. Dalal, Roshen. Hinduism: an Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books, 2014, books.google.com/books?id=zrk0AwAAQBAJ&pg=PT561&lpg=PT561&dq=indraloka+hinduism&source=bl&ots=n_TDE8_SQn&sig=b4a5vg6wUlkqPxwC5mfJkeHKP5A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjOvPTWl7zbAhWKr1kKHXUzAUoQ6AEwEnoECAMQAQ#v=onepage&q=indraloka%20hinduism&f=false.

2. Thomas Berry (1996). Religions of India: Hinduism, Yoga, Buddhism. Columbia University Press. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-0-231-10781-5.

3. "Dictionary | Buddhistdoor".

http://www.buddhistdoor.net. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

4. Helen Josephine Baroni (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 153. ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6.

5. Lisa Owen (2012). Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora. BRILL Academic. p. 25. ISBN 90-04-20629-9.

6. Bezhan, Frud (19 April 2017). "Pakistan's Forgotten Pagans Get Their Due". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 11 July 2017. About half of the Kalash practice a form of ancient Hinduism infused with old pagan and animist beliefs.

7. Barrington, Nicholas; Kendrick, Joseph T.; Schlagintweit, Reinhard (18 April 2006). A Passage to Nuristan: Exploring the Mysterious Afghan Hinterland. I.B. Tauris. p. 111. ISBN 9781845111755. Prominent sites include Hadda, near Jalalabad, but Buddhism never seems to have penetrated the remote valleys of Nuristan, where the people continued to practise an early form of polytheistic Hinduism.

8. Weiss, Mitch; Maurer, Kevin (31 December 2012). No Way Out: A Story of Valor in the Mountains of Afghanistan. Berkley Caliber. p. 299. ISBN 9780425253403. Up until the late nineteenth century, many Nuristanis practised a primitive form of Hinduism. It was the last area in Afghanistan to convert to Islam—and the conversion was accomplished by the sword.

9.

https://www.business-standard.com/artic ... 863_1.html10.

http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witz ... ligion.pdf11. name="Jamil2019">Jamil, Kashif (19 August 2019). "Uchal — a festival of shepherds and farmers of the Kalash tribe". Daily Times. p. English. Retrieved 23 January 2020. Some of their deities who are worshiped in Kalash tribe are similar to the Hindu god and goddess like Mahadev in Hinduism is called Mahandeo in Kalash tribe. ... All the tribal also visit the Mahandeo for worship and pray. After that they reach to the gree (dancing place).

12. West, Barbara A. (19 May 2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 357. ISBN 9781438119137. The Kalasha are a unique people living in just three valleys near Chitral, Pakistan, the capital of North-West Frontier Province, which borders Afghanistan. Unlike their neighbors in the Hindu Kush Mountains on both the Afghani and Pakistani sides of the border the Kalasha have not converted to Islam. During the mid-20th century a few Kalasha villages in Pakistan were forcibly converted to this dominant religion, but the people fought the conversion and once official pressure was removed the vast majority continued to practice their own religion. Their religion is a form of Hinduism that recognizes many gods and spirits and has been related to the religion of the ancient Greeks... given their Indo-Aryan language, ... the religion of the Kalasha is much more closely aligned to the Hinduism of their Indian neighbors that to the religion of Alexander the Great and his armies.

13. T. N. Madan (2003). The Hinduism Omnibus. Oxford University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-19-566411-9.

14. Sukumari Bhattacharji (2015). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–281.

15. Gopal, Madan (1990). India Through the Ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 66.

16. "War and Religion: An Encyclopedia of Faith and Conflict [3 volumes] - Google Książki".

17. Edward Delavan Perry, "Indra in the Rig-Veda". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 11.1885: 121. JSTOR 592191.

18. Jan Gonda (1989). The Indra Hymns of the Ṛgveda. Brill Archive. p. 3. ISBN 90-04-09139-4.

19. Hervey De Witt Griswold (1971). The Religion of the Ṛigveda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 177–180. ISBN 978-81-208-0745-7.

20. Alain Daniélou (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

21. Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 739–740. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

22. Wendy Doniger (2015), Indra: Indian deity, Encyclopædia Britannica

23. Naomi Appleton (2014). Narrating Karma and Rebirth: Buddhist and Jain Multi-Life Stories. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50, 98. ISBN 978-1-139-91640-0.

24. Kristi L. Wiley (2009). The A to Z of Jainism. Scarecrow Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-8108-6821-2.

25. John E. Cort (22 March 2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9.

26. T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 111. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

27. Wilkings 1882, p. 52.

28. Sita Pieris; Ellen Raven (2010). ABIA: South and Southeast Asian Art and Archaeology Index: Volume Three – South Asia. BRILL Academic. p. 232. ISBN 90-04-19148-8.

29. Friedrich Max Müller (1903). Anthropological Religion: The Gifford Lectures Delivered Before the University of Glasgow in 1891. Longmans Green. pp. 395–398.

30. Chakravarty, Uma. "ON THE ETYMOLOGY OF THE WORD 'ÍNDRA'." Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 76, no. 1/4 (1995): 27-33.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41694367.

31. Hervey De Witt Griswold (1971). The Religion of the Ṛigveda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 177–178 with footnote 1. ISBN 978-81-208-0745-7.

32. Edward Delavan Perry (1885). "Indra in the Rig-Veda". 11. Journal of the American Oriental Society: 121. JSTOR 592191.

33. Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 418 with footnote 148. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

34. John Colarusso (2014). Nart Sagas from the Caucasus: Myths and Legends from the Circassians, Abazas, Abkhaz, and Ubykhs. Princeton University Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-1-4008-6528-4.

35. Shan M. M. Winn (1995). Heaven, Heroes, and Happiness: The Indo-European Roots of Western Ideology. University Press of America. pp. 371 note 1. ISBN 978-0-8191-9860-0.

36. Uma Chakraborty (1997). Indra and Other Vedic Deities: A Euhemeristic Study. DK Printworld. pp. 91, 220. ISBN 978-81-246-0080-1.

37. Presidential Address W. H. D. Rouse Folklore, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Mar., 1907), pp. 12-23: "King of the Gods is Sakka, or Indra"

38. Wilkings 1882, p. 53.

39. Alexander Stuart Murray (1891). Manual of Mythology: Greek and Roman, Norse, and Old German, Hindoo and Egyptian Mythology, 2nd Edition. C. Scribner's sons. pp. 329–331.

40. Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. pp. 744–749.

41. Michael Janda (2000). Eleusis: Das Indogermanische Erbe Der Mysterien. Institut für Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Innsbruck. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-3-85124-675-9.

42. Eva Von Dassow (2008). State and Society in the Late Bronze Age. University Press of Maryland. pp. 77, 85–86. ISBN 978-1-934309-14-8.

43. Edward James Rapson (1955). The Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 320–321. GGKEY:FP2CEFT2WJH.

44. Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. pp. 756–759.

45. Anthony 2007, p. 462.

46. Beckwith 2009, p. 32.

47. Anthony 2007, p. 454-455.

48. Anthony 2007, p. 454.

49. Alain Daniélou (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

50. Stephanie Jamison (2015). The Rigveda –– Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0190633395.

51. ऋग्वेद: सूक्तं १.३२, Wikisource Rigveda Sanskrit text

52. Hervey De Witt Griswold (1971). The Religion of the Ṛigveda. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 180, verse 1.32.15. ISBN 978-81-208-0745-7.

53. Hervey De Witt Griswold (1971). The Religion of the Ṛigveda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 180–183 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-0745-7.

54. Arthur Berriedale Keith (1925). The Religion and Philosophy of the Veda and Upanishads. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 93–94. ISBN 978-81-208-0645-0.

55. Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. p. 758.

56. Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. p. 757.

57. Jan Gonda (1989). The Indra Hymns of the Ṛgveda. Brill Archive. pp. 4–5. ISBN 90-04-09139-4.

58. Jan Gonda (1989). The Indra Hymns of the Ṛgveda. Brill Archive. p. 12. ISBN 90-04-09139-4.

59. Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. p. 827.

60. Friedrich Max Müller (1897). Contributions to the Science of Mythology. Longmans Green. p. 828.

61. Jan Gonda (1969), The Hindu Trinity, Anthropos, Bd 63/64, H 1/2, pages 218-219

62. Jan Gonda (1969), The Hindu Trinity, Anthropos, Bd 63/64, H 1/2, pages 212-226

63. David White (2006), Kiss of the Yogini, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0226894843, pages 4, 29

64. Jamison, Stephanie (2014). The Rigveda–– the earliest religious poetry of India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0190633395.

65. Robert Hume, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, page 294 with verses 1.1.1 and footnotes

66. Paul Deussen (1997). A Sixty Upanishads Of The Veda, Volume 1. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-81-208-0430-2.

67. Robert Hume, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 295-297 with footnotes

68. Johannes Bronkhorst (2007). Greater Magadha: Studies in the Culture of Early India. BRILL. p. 128. ISBN 90-04-15719-0.

69. Robert Hume, The Thirteen Principal Upanishads, Oxford University Press, pages 297-298 with verses 1.3.13-14 and footnotes

70. Patrick Olivelle (1998). The Early Upanishads: Annotated Text and Translation. Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-19-535242-9.

71. S Krishnamoorthy (2011). Silappadikaram. Bharathi Puthakalayam.

72. S Krishnamoorthy (2011). Silappadikaram. Bharathi Puthakalayam. pp. 31–36.

73. Wilkings 1882.

74. Roshen Dalal (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books India. pp. 190, 251. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

75. Zimmer, Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization, ed. Joseph Campbell (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1962), p. 3-11

76. [1]

77. Alain Daniélou (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

78. Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 75.

79. (Masson-Oursel and Morin, 326).

80. Alain Daniélou (1991). The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

81. Trainor 2004, p. 62.

82. Merv Fowler (1999). Buddhism: Beliefs and Practices. Sussex Academic Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-898723-66-0., Quote: "For a vast majority of Buddhists in Theravadin countries, however, the order of monks is seen by lay Buddhists as a means of gaining the most merit in the hope of accumulating good karma for a better rebirth."

83. Christopher Gowans (2004). Philosophy of the Buddha: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-134-46973-4.

84. Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. pp. 230–231. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

85. John Clifford Holt; Jacob N. Kinnard; Jonathan S. Walters (2012). Constituting Communities: Theravada Buddhism and the Religious Cultures of South and Southeast Asia. State University of New York Press. pp. 45–46, 57–64, 108. ISBN 978-0-7914-8705-1.

86. E. B. Cowell & Francis A. Davis 1969, pp. 5, 21.

87. E. B. Cowell & Francis A. Davis 1969, p. 44.

88. E. B. Cowell & Francis A. Davis 1969, p. 71 footnote 1.

89. E. B. Cowell & Francis A. Davis 1969, p. 205.

90. Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

91. Sanskrit: Rigveda 5.34, Wikisource;

English Translation: HH Wilson (1857). Rig-veda Sanhita: A Collection of Ancient Hindu Hymns. Trübner & Company. pp. 288–291, 58–61.

92. "Part 2 - Evening Chanting".

http://www.Watpasantidhamma.org. Retrieved 18 January2019.

93. Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). From Stone to Flesh: A Short History of the Buddha. University of Chicago Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-226-49321-3.

94. K. Walton Dobbins (1968), Two Gandhāran Reliquaries, East and West, Volume 18, Number 1/2 (March–June 1968), pages 151-162

95. Waraporn Poopongpan (2007), "Thai Kingship during the Ayutthaya Period: A Note on Its Divine Aspects Concerning Indra." Silpakorn University International Journal, Volume 7, pages 143-171

96. Indra's Net (book)#cite note-FOOTNOTEMalhotra20144-10

97. Twelve Heavenly Deities (Devas) Nara National Museum, Japan

98. S Biswas (2000), Art of Japan, Northern, ISBN 978-8172112691, page 184

99. Willem Frederik Stutterheim et al (1995), Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia, ISBN 978-8170172512, pages xiv-xvi

100. Adrian Snodgrass (2007), The Symbolism of the Stupa, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120807815, pages 120-124, 298-300

101. "กรุงเทพมหานคร". Royal Institute Newsletter. 3 (31). December 1993. Reproduced in กรุงเทพมหานคร [Krung Thep Mahanakhon] (in Thai). Archived from the originalon 10 December 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

102. Goswamy 2014, p. 245.

103. Lisa Owen (2012). Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora. BRILL Academic. pp. 25–28. ISBN 90-04-20629-9.

104. Helmuth von Glasenapp (1999). Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

105. Lisa Owen (2012). Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora. BRILL Academic. pp. 29–33. ISBN 90-04-20629-9.

Bibliography• Goswamy, B.N. (2014), The Spirit of Indian Painting: Close Encounters with 100 Great Works 1100-1900, Penguin Books, ISBN 978-0-670-08657-3

• Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World, Princeton University Press

• Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, Princeton University Press

• E. B. Cowell; Francis A. Davis (1969). Buddhist Mahayana Texts. Courier Corporation. ISBN 978-0-486-25552-1.

• Wilkings, W.J. (1882), Hindu mythology, Vedic & Puranic, Elibron Classics (2001 reprint of 1882 edition by Thaker, Spink & Co., Calcutta), archived from the original on 9 October 2014

• Masson-Oursel, P.; Morin, Louise (1976). "Indian Mythology." In New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology, pp. 325–359. New York: The Hamlyn Publishing Group.

• Janda, M., Eleusis, das indogermanische Erbe der Mysterien (1998).

• Trainor, Kevin (2004), Buddhism: The Illustrated Guide, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517398-7

• Chakravarty, Uma. "On the etymology of the word 'ÍNDRA'." Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute 76, no. 1/4 (1995): 27-33.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/41694367.

External links• Indra and Skanda deities in Korean Buddhism, Phil Lee, Chicago Divinity School

• Indra, Lord of Storms and King of the Gods' Realm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

• Indra wood idol – 13th century, Kamakura period, Japan