Manusmriti

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/7/20

-- Manu (Hinduism), by Wikipedia

-- Manusmriti, by Wikipedia

-- Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Menu, According to the Gloss of Culluca. Comprising the Indian System of Duties, Religious and Civil, Verbally translated from the original Sanscrit, With a Preface, by Sir William Jones

-- Matsya, by Wikipedia

-- Sethona. A Tragedy. As it is Performed at the Theatre-Royal in Drury-Lane, by Alexander Dow

-- Menes [Mneues], by Wikipedia

-- Mannus, by Wikipedia

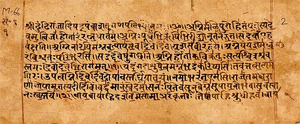

Vyasa too, the son of Parasara before mentioned, has decided, that 'the Veda with its Angas, or the six compositions deduced from it, the revealed system of medicine, the Puranas, or sacred histories, and the code of Menu were four works of supreme authority, which ought never to be shaken by arguments merely human.’

It is the general opinion of Pandits, that Brahma taught his laws to Menu in a hundred thousand verses, which Menu explained to the primitive world, in the very words of the book now translated, where he names himself, after the manner of ancient sages, in the third person, but in a short preface to the law tract of Nared, it is asserted, that 'Menu, having written the laws of Brahma in a hundred thousand slocas or couplets, arranged under twenty-four heads in a thousand chapters, delivered the work to Nared, the sage among gods, who abridged it, for the use of mankind, in twelve thousand verses, and gave them to a son of Bhrigu, named Sumati, who, for greater ease to the human race, reduced them to four thousand; that mortals read only the second abridgement by Sumati, while the gods of the lower heaven, and the band of celestial musicians, are engaged in studying the primary code, beginning with the fifth verse, a little varied, of the work now extant on earth; but that nothing remains of NARED’s abridgement, except an elegant epitome of the ninth original title on the administration of justice.' Now, since these institutes consist only of two thousand six hundred and eighty five verses, they cannot be the whole work ascribed to Sumati, which is probably distinguished by the name of the Vriddha, or ancient Manava, and cannot be found entire; though several passages from it, which have been preserved by tradition, are occasionally cited in the new digest.

A number of glosses or comments on Menu were composed by the Munis, or old philosophers, whose treatises, together with that before us, constitute the Dherma sastra, in a collective sense, or Body of Law; among the more modern commentaries, that called Medhatithi, that by Govindaraja, and that by Dharani-Dhera, were once in the greatest repute; but the first was reckoned prolix and unequal; the second concise but obscure; and the third often erroneous. At length appeared Culluca Bhatta; who, after a painful course of study and the collation of numerous manuscripts, produced a work, of which it may, perhaps, be said very truly, that it is the shortest, yet the most luminous, the least ostentatious, yet the most learned, the deepest, yet the most agreeable, commentary ever composed on any author ancient or modern, European or Asiatick. The Pandits care so little for genuine chronology, that none of them can tell me the age of Culluca, whom they always name with applause; but he informs us himself, that he was a Brahmen of the Varendra tribe, whose family had been long settled in Gaur or Bengal, but that he had chosen his residence among the learned, on the banks of the holy river at Casi. His text and interpretation I have almost implicitly followed, though I had myself collated many copies of Menu, and among them a manuscript of a very ancient date: his gloss is here printed in Italicks; and any reader, who may choose to pass it over as if unprinted, will have in Roman letters an exact version of the original, and may form some idea of its character and structure, as well as of the Sanscrit idiom which must necessarily be preserved in a verbal translation; and a translation, not scrupulously verbal, would have been highly improper in a work on so delicate and momentous a subject as private and criminal jurisprudence.

Should a series of Brahmens omit, for three generations, the reading of Menu, their sacerdotal class, as all the Pandits assure me, would in strictness be forfeited; but they must explain it only to their pupils of the three highest classes; and the Brahmen, who read it with me, requested most earnestly, that his name might be concealed; nor would he have read it for any consideration on a forbidden day of the moon, or without the ceremonies prescribed in the second and fourth chapters for a lecture on the Veda: so great, indeed, is the idea of sanctity annexed to this book, that, when the chief native magistrate at Banares endeavoured, at my request, to procure a Persian translation of it, before I had a hope of being at any time able to understand the original, the Pandits of his court unanimously and positively refused to assist in the work; nor should I have procured it at all, if a wealthy Hindu at Gaya had not caused the version to be made by some of his dependants, at the desire of my friend Mr. [Jacques Louis Law de Clapernon? or Baron Jean Law de Lauriston?] Law. [1776]"In relation to his Translation, it was made by the orders of Mr. Barthelemi, First Counselor in Pondicherry. Having a great number of interpreters for him, he had them translate some Indian works with all possible accuracy: but the wars of India & the ruin of Pondicherry resulted in the loss of all that he had gathered on these objects: and only the last translation of Zozur, of which only one complete copy remains, between the hands of M. Teissier de la Tour nephew of M. leConsr. Barthelemy. It's certain the one that we made the copy that we have in the Library of His Majesty, and which no doubt had not had time to complete when M. de Modave embarked to return to Europe."

I have not been able to gather any information on Tessier -- or Teissier -- de la Tour. Louis Barthelemy is much better known; although his career in India runs parallel to that of Porcher des Oulches, of the two he is the more prominent one and holds the highest offices. His name appears repeatedly in the official documents of the French Company. He was born at Montpellier, circa 1695, came to India in 1729, and stayed there until his death at Pondicherry, on 29 July 1760. He served at Mahe, was a member of the council at Chandernagore, and was called to Pondicherry in 1742. His duties at Pondicherry were twice interrupted in later years: in 1748 he was appointed governor of Madras, and in 1753-54 he preceded Porcher as commander of Karikal. He rose to the rank of "second du Conseil Superieur," and in the short period in 1755, between the departure of Godeheu and the arrival of de Leyrit, Barthelemy's name appears first on all official documents. It should perhaps be mentioned, first, that on 22 February 1751 Barthelemy represented the father of the bride at the wedding of Jacques Law -- Dupleix was the witness for the bridegroom --, and second, that on 8 August 1758 he was godfather of Jacques Louis Law. These two entries seem to suggest that he was indeed close to the Law family, whose interpreter has been given credit for the translation of the EzV (see p. 28). It should also be pointed out that Barthelemy died more than half a year after Maudave -- and the EzV -- reached Lorient on 2 February 1760.

-- The Ezourvedam Manuscripts, Excerpt from Ezourvedam: A French Veda of the Eighteenth Century, Edited with an Introduction by Ludo RocherThe first Director General for the [French East India] Company was François de la Faye,...

La Faye was the owner of an extensive art collection, two hotels in Paris, and another in Versailles. When he acquired the ancient château de Condé in 1719, he commissioned the most fashionable artists of his time and the architect Giovanni Niccolò Servandoni for elaborate improvements....

The Marquis was a member of the French Academy, a director of the French India Company, and accordingly, was a very rich man. In his mansion in Paris, he often received such famous people as Voltaire and Crébillon...

At a later date, the castle belonged to the Count de la Tour du Pin Lachaux, through his marriage with the niece of the Marquis de la Faye...

In 1814, the Countess de Sade, the daughter-in-law of the famous Marquis de Sade, inherited Condé from her cousin, La Tour du Pin. Since this time and up to 1983, the castle remained the property of the Sade family, who restored it with much care after the two World Wars.

-- French East India Company, by Wikipedia

The Persian translation of Menu, like all others from the Sanscrit into that language, is a rude intermixture of the text, loosely rendered, with some old or new comment, and often with the crude notions of the translator; and though it expresses the general sense of the original, yet it swarms with errours, imputable partly to haste, and partly to ignorance: thus where Menu says, that emissaries are the eyes of a prince, the Persian phrase makes him ascribe four eyes to the person of a king; for the word char, which means an emissary in Sanscrit, signifies four in the popular dialect.

-- Institutes of Hindu Law: Or, The Ordinances of Menu, According to the Gloss of Culluca. Comprising the Indian System of Duties, Religious and Civil, Verbally translated from the original Sanscrit, With a Preface, by Sir William Jones

Highlights:

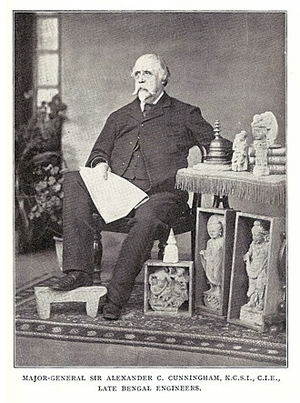

The Manusmṛiti ... was one of the first Sanskrit texts to have been translated into English in 1776, by Sir William Jones, and was used to formulate the Hindu law by the British colonial government...

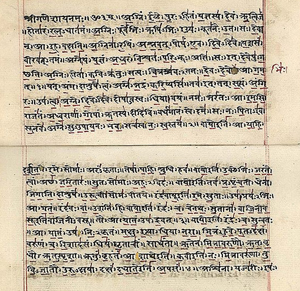

Over fifty manuscripts of the Manusmriti are now known, but the earliest discovered, most translated and presumed authentic version since the 18th century has been the "Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) manuscript with Kulluka Bhatta commentary". Modern scholarship states this presumed authenticity is false, and the various manuscripts of Manusmriti discovered in India are inconsistent with each other, and within themselves, raising concerns of its authenticity, insertions and interpolations made into the text in later times...

The title Manusmriti is a relatively modern term and a late innovation, probably coined because the text is in a verse form...

[T]he text version in modern use, according to Olivelle, is likely the work of a single author or a chairman with research assistants.

Manusmriti, Olivelle states, was not a new document, it drew on other texts, and it reflects "a crystallization of an accumulated knowledge" in ancient India....

The text is composed in metric Shlokas (verses), in the form of a dialogue between an exalted teacher and disciples who are eager to learn about the various aspects of dharma....

The verses 12.1, 12.2 and 12.82 are transitional verses. This section is in a different style than the rest of the text, raising questions whether this entire chapter was added later. While there is evidence that this chapter was extensively redacted over time, however it is unclear whether the entire chapter is of a later era....

The structure and contents of the Manusmriti suggest it to be a document predominantly targeted at the Brahmins (priestly class) and the Kshatriyas (king, administration and warrior class). The text dedicates 1,034 verses, the largest portion, on laws for and expected virtues of Brahmins, and 971 verses for Kshatriyas...

Chapter 7 of the Manusmriti discusses the duties of a king, what virtues he must have, what vices he must avoid. In verses 7.54 - 7.76, the text identifies precepts to be followed in selecting ministers, ambassadors and officials, as well as the characteristics of well fortified capital. Manusmriti then lays out the laws of just war, stating that first and foremost, war should be avoided by negotiations and reconciliations. If war becomes necessary, states Manusmriti, a soldier must never harm civilians, non-combatants or someone who has surrendered, that use of force should be proportionate, and other rules. Fair taxation guidelines are described in verses 7.127 to 7.137...

Sinha, for example, states that less than half, or only 1,214 of the 2,685 verses in Manusmriti, may be authentic. Further, the verses are internally inconsistent. Verses such as 3.55-3.62 of Manusmriti, for example, glorify the position of women, while verse such as 9.3 and 9.17 do the opposite. Other passages found in Manusmriti, such as those relating to Ganesha, are modern era insertions and forgeries...

There are so many contradictions in the printed volume that, if you accept one part, you are bound to reject those parts that are wholly inconsistent with it. (...) Nobody is in possession of the original text...

Scholars doubt Manusmriti was ever administered as law text in ancient or medieval Hindu society. David Buxbaum states, "in the opinion of the best contemporary orientalists, it [Manusmriti] does not, as a whole, represent a set of rules ever actually administered in Hindustan. It is in great part an ideal picture of that which ... ought to be law".

Donald Davis writes, "there is no historical evidence for either an active propagation or implementation of Dharmasastra [Manusmriti] by a ruler or any state – as distinct from other forms of recognizing, respecting and using the text. Thinking of Dharmasastra as a legal code and of its authors as lawgivers is thus a serious misunderstanding of its history"....

Prior to the British colonial rule, Sharia (Islamic law) for Muslims in South Asia had been codified as Fatawa-e-Alamgiri, but laws for non-Muslims –- such as Hindus, Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis –- were not codified during the 600 years of Islamic rule...

In the 18th century, the earliest British of the East India Company acted as agents of the Mughal emperor... The administration ... relying upon co-opted local intermediaries that were mostly Muslims and some Hindus in various princely states... exercised power by ... adapting to law practices as explained by the local intermediaries. The existing legal texts for Muslims, and resurrected Manusmriti manuscript thus helped the colonial state ...

For Muslims of India, the British accepted sharia as the legal code for Muslims, based on texts such the al-Sirjjiyah and Fatawa-i Alamgiri written under sponsorship of Aurangzeb. For Hindus and other non-Muslims such as Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis and Tribal people, this information was unavailable. The substance of Hindu law, was derived by the British colonial officials from Manusmriti...

Manusmriti ... was not in use for centuries during the Islamic rule period of India. The officials resurrected Manusmriti, constructed statements of positive law from the text for non-Muslims, in order to remain faithful to its policy of using sharia for the South Asian Muslim population. Manusmriti, thus played a role in constructing the Anglo-Hindu law, as well as Western perceptions about ancient and medieval era Hindu culture from the colonial times. Abdullahi Ahmed An-Na'im states the significance and role of Manusmriti in governing India during the colonial era as follows (abridged),The [British] colonial administration began the codification of Hindu and Muslim laws in 1772 and continued through the next century, with emphasis on certain texts as the authentic "sources" of the law and custom of Hindus and Muslims, which in fact devalued and retarded those dynamic social systems. The codification of complex and interdependent traditional systems froze certain aspects of the status of women, for instance, outside the context of constantly evolving social and economic relations, which in effect limited or restricted women's rights. The selectivity of the process, whereby colonial authorities sought the assistance of Hindu and Muslim religious elites in understanding the law, resulted in the Brahminization and Islamization of customary laws [in British India]. For example, the British orientalist scholar William Jones translated the key texts Al Sirjjiyah in 1792 as the Mohammedan Law of Inheritance, and Manusmriti in 1794 as the Institutes of Hindu Law or the Ordinances of Manu. In short, British colonial administrators reduced centuries of vigorous development of total ethical, religious and social systems to fit their own preconceived European notions of what Muslim and Hindu "law" should be...

Along with Manusmriti (Manava Dharmasastra), ancient India had between eighteen and thirty six competing Dharma-sastras, states John Bowker. Many of these texts have been lost completely or in parts.

-- Manusmriti, by Wikipedia

The Manusmṛiti (Sanskrit: मनुस्मृति), also spelled as Manusmruti,[1] is an ancient legal text among the many Dharmaśāstras of Hinduism.[2] It was one of the first Sanskrit texts to have been translated into English in 1776, by Sir William Jones,[2] and was used to formulate the Hindu law by the British colonial government.[3][4] It can be considered as the world's first constitution as it contains laws regarding society, taxes, warfare, etc.

To possess ourselves of a clear idea of what government is, or ought to be, we must trace it to its origin. In doing this we shall easily discover that governments must have arisen either out of the people or over the people. Mr. Burke has made no distinction. He investigates nothing to its source, and therefore he confounds everything; but he has signified his intention of undertaking, at some future opportunity, a comparison between the constitution of England and France. As he thus renders it a subject of controversy by throwing the gauntlet, I take him upon his own ground. It is in high challenges that high truths have the right of appearing; and I accept it with the more readiness because it affords me, at the same time, an opportunity of pursuing the subject with respect to governments arising out of society.

But it will be first necessary to define what is meant by a Constitution. It is not sufficient that we adopt the word; we must fix also a standard signification to it.

A constitution is not a thing in name only, but in fact. It has not an ideal, but a real existence; and wherever it cannot be produced in a visible form, there is none. A constitution is a thing antecedent to a government, and a government is only the creature of a constitution. The constitution of a country is not the act of its government, but of the people constituting its government. It is the body of elements, to which you can refer, and quote article by article; and which contains the principles on which the government shall be established, the manner in which it shall be organised, the powers it shall have, the mode of elections, the duration of Parliaments, or by what other name such bodies may be called; the powers which the executive part of the government shall have; and in fine, everything that relates to the complete organisation of a civil government, and the principles on which it shall act, and by which it shall be bound. A constitution, therefore, is to a government what the laws made afterwards by that government are to a court of judicature. The court of judicature does not make the laws, neither can it alter them; it only acts in conformity to the laws made: and the government is in like manner governed by the constitution.

Can, then, Mr. Burke produce the English Constitution? If he cannot, we may fairly conclude that though it has been so much talked about, no such thing as a constitution exists, or ever did exist, and consequently that the people have yet a constitution to form.

Mr. Burke will not, I presume, deny the position I have already advanced- namely, that governments arise either out of the people or over the people. The English Government is one of those which arose out of a conquest, and not out of society, and consequently it arose over the people; and though it has been much modified from the opportunity of circumstances since the time of William the Conqueror, the country has never yet regenerated itself, and is therefore without a constitution.

I readily perceive the reason why Mr. Burke declined going into the comparison between the English and French constitutions, because he could not but perceive, when he sat down to the task, that no such a thing as a constitution existed on his side the question. His book is certainly bulky enough to have contained all he could say on this subject, and it would have been the best manner in which people could have judged of their separate merits. Why then has he declined the only thing that was worth while to write upon? It was the strongest ground he could take, if the advantages were on his side, but the weakest if they were not; and his declining to take it is either a sign that he could not possess it or could not maintain it.

Mr. Burke said, in a speech last winter in Parliament, "that when the National Assembly first met in three Orders (the Tiers Etat, the Clergy, and the Noblesse), France had then a good constitution." This shows, among numerous other instances, that Mr. Burke does not understand what a constitution is. The persons so met were not a constitution, but a convention, to make a constitution.

The present National Assembly of France is, strictly speaking, the personal social compact. The members of it are the delegates of the nation in its original character; future assemblies will be the delegates of the nation in its organised character. The authority of the present Assembly is different from what the authority of future Assemblies will be. The authority of the present one is to form a constitution; the authority of future assemblies will be to legislate according to the principles and forms prescribed in that constitution; and if experience should hereafter show that alterations, amendments, or additions are necessary, the constitution will point out the mode by which such things shall be done, and not leave it to the discretionary power of the future government.

A government on the principles on which constitutional governments arising out of society are established, cannot have the right of altering itself. If it had, it would be arbitrary. It might make itself what it pleased; and wherever such a right is set up, it shows there is no constitution. The act by which the English Parliament empowered itself to sit seven years, shows there is no constitution in England. It might, by the same self-authority, have sat any great number of years, or for life. The bill which the present Mr. Pitt brought into Parliament some years ago, to reform Parliament, was on the same erroneous principle. The right of reform is in the nation in its original character, and the constitutional method would be by a general convention elected for the purpose. There is, moreover, a paradox in the idea of vitiated bodies reforming themselves.

From these preliminaries I proceed to draw some comparisons....

-- Rights of Man, by Thomas Paine

Over fifty manuscripts of the Manusmriti are now known, but the earliest discovered, most translated and presumed authentic version since the 18th century has been the "Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) manuscript with Kulluka Bhatta commentary".[5] Modern scholarship states this presumed authenticity is false, and the various manuscripts of Manusmriti discovered in India are inconsistent with each other, and within themselves, raising concerns of its authenticity, insertions and interpolations made into the text in later times.[5][6]

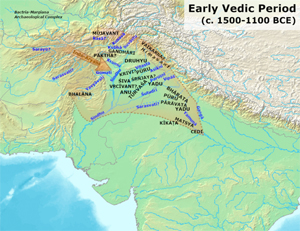

The metrical text is in Sanskrit, is variously dated to be from the 2nd century BCE to 3rd century CE, and it presents itself as a discourse given by Manu (Svayambhuva) and Bhrigu on dharma topics such as duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and others.

Matsya protecting Vaivasvata Manu and the seven sages at the time of Deluge/Great Flood

Manu (Sanskrit: मनु) is a term found with various meanings in Hinduism. In early texts, it refers to the archetypal man, or to the first man (progenitor of humanity). The Sanskrit term for 'human', मानव (IAST: mānava) means 'of Manu' or 'children of Manu'. In later texts, Manu is the title or name of fourteen mystical Kshatriya rulers of earth, or alternatively as the head of mythical dynasties that begin with each cyclic kalpa (aeon) when the universe is born anew. The title of the text Manusmriti uses this term as a prefix, but refers to the first Manu – Svayambhuva, the spiritual son of Brahma.

According to Puranas, each kalpa consists of fourteen Manvantaras, and each Manvantara is headed by a different Manu. The current universe, is asserted to be ruled by the 7th Manu named Vaivasvata.

In Vishnu Purana, Vaivasvata, also known as Sraddhadeva or Satyavrata, was the king of Dravida before the great flood. He was warned of the flood by the Matsya (fish) avatar of Vishnu, and built a boat that carried the Vedas, Manu's family and the seven sages to safety, helped by Matsya. The tale is repeated with variations in other texts, including the Mahabharata and a few other Puranas. It is similar to other flood such as that of Gilgamesh and Noah.

-- Manu (Hinduism), by Wikipedia

The text's fame spread outside Bharat (India), long before the colonial era. The medieval era Buddhistic law of Myanmar and Thailand are also ascribed to Manu,[7][8] and the text influenced past Hindu kingdoms in Cambodia and Indonesia.[9]

Manusmriti is also called the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra or Laws of Manu.[10]

Nomenclature

The title Manusmriti is a relatively modern term and a late innovation, probably coined because the text is in a verse form.[10] The over fifty manuscripts discovered of the text, never use this title, but state the title as Manava Dharmasastra (Sanskrit: मानवधर्मशास्त्र) in their colophons at the end of each chapter. In modern scholarship, these two titles refer to the same text.[10]

Chronology

Eighteenth-century philologists Sir William Jones and Karl Wilhelm Friedrich Schlegel assigned Manusmriti to the period of around 1250 BCE and 1000 BCE respectively, which from later linguistic developments is untenable due to the language of the text which must be dated later than the late Vedic texts such as the Upanishads which are themselves dated a few centuries later, around 500 BCE.[11] Later scholars, shifted the chronology of the text to between 200 BCE and 200 CE.[12][13] Olivelle adds that numismatics evidence, and the mention of gold coins as a fine, suggest that text may date to the 2nd or 3rd century CE.[14]

Most scholars consider the text a composite produced by many authors put together over a long period. Olivelle states that the various ancient and medieval Indian texts claim revisions and editions were derived from the original text with 100,000 verses and 1,080 chapters. However, the text version in modern use, according to Olivelle, is likely the work of a single author or a chairman with research assistants.[15]

Manusmriti, Olivelle states, was not a new document, it drew on other texts, and it reflects "a crystallization of an accumulated knowledge" in ancient India.[16] The root of theoretical models within Manusmriti rely on at least two shastras that pre-date it: artha (statecraft and legal process), and dharma (an ancient Indian concept that includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and others discussed in various Dharmasutras older than Manusmriti).[16] Its contents can be traced to Kalpasutras of the Vedic era, which led to the development of Smartasutras consisting of Grihyasutras and Dharmasutras.[17] The foundational texts of Manusmriti include many of these sutras, all from an era preceding the common era. Most of these ancient texts are now lost, and only four of have survived: the law codes of Apastamba, Gautama, Baudhayana and Vasishtha.[18]

Structure

The modern version of the text has been subdivided into twelve Adhyayas (chapters), but the original text had no such division.[19] The text covers different topics, and is unique among ancient Indian texts in using “transitional verses” to mark the end of one subject and the start of the next.[19] The text can be broadly divided into four, each of different length. and each further divided into subsections:[19]

1. Creation of the world

2. Source of dharma

3. The dharma of the four social classes

4. Law of karma, rebirth and final liberation

The text is composed in metric Shlokas (verses), in the form of a dialogue between an exalted teacher and disciples who are eager to learn about the various aspects of dharma.[20] The first 58 verses are attributed by the text to Manu, while the remaining more than two thousand verses are attributed to his student Bhrigu.[20] Olivelle lists the subsections as follows:[21]

Sources of the law

The Dharmasya Yonih (Sources of the Law) has twenty-four verses, and one transition verse.[21] These verses state what the text considers as the proper and just sources of law:

वेदोऽखिलो धर्ममूलं स्मृतिशीले च तद्विदाम् । आचारश्चैव साधूनामात्मनस्तुष्टिरेव च ॥

Translation 1: The whole Veda is the (first) source of the sacred law, next the tradition and the virtuous conduct of those who know the (Veda further), also the customs of holy men, and (finally) self-satisfaction (Atmana santushti).[22]

Translation 2: The root of the religion is the entire Veda, and (then) the tradition and customs of those who know (the Veda), and the conduct of virtuous people, and what is satisfactory to oneself.[23]

— Manusmriti 2.6

वेदः स्मृतिः सदाचारः स्वस्य च प्रियमात्मनः । एतच्चतुर्विधं प्राहुः साक्षाद् धर्मस्य लक्षणम् ॥

Translation 1: The Veda, the sacred tradition, the customs of virtuous men, and one's own pleasure, they declare to be the fourfold means of defining the sacred law.[22]

Translation 2: The Veda, tradition, the conduct of good people, and what is pleasing to oneself – they say that is four fold mark of religion.[23]

— Manusmriti 2.12

This section of Manusmriti, like other Hindu law texts, includes fourfold sources of Dharma, states Levinson, which include Atmana santushti (satisfaction of one's conscience), Sadachara (local norms of virtuous individuals), Smriti and Sruti.[24][25][26]

Dharma of the four Varnas

Further information: Varna (Hinduism)

• 3.1 Rules Relating to Law (2.25 – 10.131)

• 3.1.1 Rules of Action in Normal Times (2.26 – 9.336)

• 3.1.1.1 Fourfold Dharma of a Brahmin (2.26 – 6.96) (contains the longest section of Manusmriti, 3.1, called dharmavidhi)[19]

• 3.1.1.2 Rules of Action for a King (7.1 – 9.324) (contains 960 verses, includes description of institutions and officials of state, how officials are to be appointed, tax laws, rules of war, the role and limits on the power of the king, and long sections on eighteen grounds for litigation, including those related to non-delivery under contract, breach of contract, non-payment of wages, property disputes, inheritance disputes, humiliation and defamation, physical assault, theft, violence of any form, injury, sexual crimes against women, public safety, and others; the section also includes rules of evidence, rules on interrogation of witnesses, and the organisation of court system)[27]

• 3.1.1.3 Rules of Action for Vaiśyas and Śūdras (9.326 – 9.335) (shortest section, eight rules for Vaishyas, two for Shudras, but some applicable laws to these two classes are discussed generically in verses 2.26 – 9.324)[28]

• 3.1.2 Rules of Action in Times of Adversity (10.1 – 11.129) (contains revised rules on the state machinery and four varnas in the times of war, famine or other emergencies)[29]

• 3.2 Rules Relating to Penance (11.1 – 11.265) (includes rules of proportionate punishment; instead of fines, incarceration or death, discusses penance or social isolation as a form of punishment for certain crimes)[29]

The verses 6.97, 9.325, 9.336 and 10.131 are transitional verses.[21] Olivelle notes instances of likely interpolation and insertions in the notes to this section, in both the presumed vulgate version and the critical edition.[30]

Determination of Karmayoga

The verses 12.1, 12.2 and 12.82 are transitional verses.[21] This section is in a different style than the rest of the text, raising questions whether this entire chapter was added later. While there is evidence that this chapter was extensively redacted over time, however it is unclear whether the entire chapter is of a later era.[31]

• 4.1 Fruits of Action (12.3-81) (section on actions and consequences, personal responsibility, action as a means of moksha – the highest personal bliss)[31]

• 4.2 Rules of Action for Supreme Good (12.83-115) (section on karma, duties and responsibilities as a means of supreme good)[31]

The closing verses of Manusmriti declares,

एवं यः सर्वभूतेषु पश्यत्यात्मानमात्मना । स सर्वसमतामेत्य ब्रह्माभ्येति परं पदम् ॥

He who thus recognizes in his individual soul (Self, Atman), the universal soul that exists in all beings,

becomes equal-minded towards all, and enters the highest state, Brahman.

— Manusmriti 12.125, Calcutta manuscript with Kulluka Bhatta commentary[32][33]

Contents

The structure and contents of the Manusmriti suggest it to be a document predominantly targeted at the Brahmins (priestly class) and the Kshatriyas (king, administration and warrior class).[34] The text dedicates 1,034 verses, the largest portion, on laws for and expected virtues of Brahmins, and 971 verses for Kshatriyas.[35] The statement of rules for the Vaishyas (merchant class) and the Shudras (artisans and working class) in the text is extraordinarily brief. Olivelle suggests that this may be because the text was composed to address the balance "between the political power and the priestly interests", and because of the rise in foreign invasions of India in the period it was composed.[34]

On virtues and outcast

Manusmriti lists and recommends virtues in many verses. For example, verse 6.75 recommends non-violence towards everyone and temperance as key virtues,[36][37] while verse 10.63 preaches that all four varnas must abstain from injuring any creature, abstain from falsehood and abstain from appropriating property of others.[38][39]

Similarly, in verse 4.204, states Olivelle, some manuscripts of Manusmriti list the recommended virtues to be, "compassion, forbearance, truthfulness, non-injury, self-control, not desiring, meditation, serenity, sweetness and honesty" as primary, and "purification, sacrifices, ascetic toil, gift giving, vedic recitation, restraining the sexual organs, observances, fasts, silence and bathing" as secondary.[40] A few manuscripts of the text contain a different verse 4.204, according to Olivelle, and list the recommended virtues to be, "not injuring anyone, speaking the truth, chastity, honesty and not stealing" as central and primary, while "not being angry, obedience to the teacher, purification, eating moderately and vigilance" to desirable and secondary.[40]

In other discovered manuscripts of Manusmriti, including the most translated Calcutta manuscript, the text declares in verse 4.204 that the ethical precepts under Yamas such as Ahimsa (non-violence) are paramount while Niyamas such as Ishvarapranidhana (contemplation of personal god) are minor, and those who do not practice the Yamas but obey the Niyamas alone become outcasts.[41][42]

On personal choices, behaviours and morals

Manusmriti has numerous verses on duties a person has towards himself and to others, thus including moral codes as well as legal codes.[43] This is similar to, states Olivelle, the modern contrast between informal moral concerns to birth out of wedlock in the developed nations, along with simultaneous legal protection for children who are born out of wedlock.[43]

Personal behaviours covered by the text are extensive. For example, verses 2.51-2.56, recommend that a monk must go on his begging round, collect alms food and present it to his teacher first, then eat. One should revere whatever food one gets and eat it without disdain, states Manusmriti, but never overeat, as eating too much harms health.[44] In verse 5.47, the text states that work becomes without effort when a man contemplates, undertakes and does what he loves to do and when he does so without harming any creature.[45]

Numerous verses relate to the practice of meat eating, how it causes injury to living beings, why it is evil, and the morality of vegetarianism.[43] Yet, the text balances its moral tone as an appeal to one's conscience, states Olivelle. For example, verse 5.56 as translated by Olivelle states, "there is no fault in eating meat, in drinking liquor, or in having sex; that is the natural activity of creatures. Abstaining from such activity, however, brings greatest rewards."[46]

On rights of women

Manusmriti offers an inconsistent and internally conflicting perspective on women's rights.[47] The text, for example, declares that a marriage cannot be dissolved by a woman or a man, in verse 8.101-8.102.[48] Yet, the text, in other sections, allows either to dissolve the marriage. For example, verses 9.72-9.81 allow the man or the woman to get out of a fraudulent marriage or an abusive marriage, and remarry; the text also provides legal means for a woman to remarry when her husband has been missing or has abandoned her.[49]

It preaches chastity to widows such as in verses 5.158-5.160, opposes a woman marrying someone outside her own social class as in verses 3.13-3.14.[50] In other verses, such as 2.67-2.69 and 5.148-5.155, Manusmriti preaches that as a girl, she should obey and seek protection of her father, as a young woman her husband, and as a widow her son; and that a woman should always worship her husband as a god.[51] In verses 3.55-3.56, Manusmriti also declares that "women must be honored and adorned", and "where women are revered, there the gods rejoice; but where they are not, no sacred rite bears any fruit".[52][53] Elsewhere, in verses 5.147-5.148, states Olivelle, the text declares, "a woman must never seek to live independently".[54]

Simultaneously, states Olivelle, the text presupposes numerous practices such as marriages outside one's varna (see anuloma and pratiloma), such as between a Brahmin man and a Shudra woman in verses 9.149-9.157, a widow getting pregnant with a child of a man she is not married to in verses 9.57-9.62, marriage where a woman in love elopes with her man, and then grants legal rights in these cases such as property inheritance rights in verses 9.143-9.157, and the legal rights of the children so born.[55] The text also presumes that a married woman may get pregnant by a man other than her husband, and dedicates verses 8.31-8.56 to conclude that the child's custody belongs to the woman and her legal husband, and not to the man she got pregnant with.[56][57]

Manusmriti provides a woman with property rights to six types of property in verses 9.192-9.200. These include those she received at her marriage, or as gift when she eloped or when she was taken away, or as token of love before marriage, or as gifts from her biological family, or as received from her husband subsequent to marriage, and also from inheritance from deceased relatives.[58]

Flavia Agnes states that Manusmriti is a complex commentary from women's rights perspective, and the British colonial era codification of women's rights based on it for Hindus, and from Islamic texts for Muslims, picked and emphasised certain aspects while it ignored other sections.[47] This construction of personal law during the colonial era created a legal fiction around Manusmriti's historic role as a scripture in matters relating to women in South Asia.[47][59]

On statecraft and rules of war

Chapter 7 of the Manusmriti discusses the duties of a king, what virtues he must have, what vices he must avoid.[60] In verses 7.54 - 7.76, the text identifies precepts to be followed in selecting ministers, ambassadors and officials, as well as the characteristics of well fortified capital. Manusmriti then lays out the laws of just war, stating that first and foremost, war should be avoided by negotiations and reconciliations.[60][61] If war becomes necessary, states Manusmriti, a soldier must never harm civilians, non-combatants or someone who has surrendered, that use of force should be proportionate, and other rules.[60] Fair taxation guidelines are described in verses 7.127 to 7.137.[60][61]

Authenticity and inconsistencies in various manuscripts

Patrick Olivelle, credited with a 2005 translation of Manusmriti published by the Oxford University Press, states the concerns in postmodern scholarship about the presumed authenticity and reliability of Manusmriti manuscripts.[5] He writes (abridged),

The MDh [Manusmriti] was the first Indian legal text introduced to the western world through the translation of Sir William Jones in 1794. (...) All the editions of the MDh, except for Jolly's, reproduce the text as found in the [Calcutta] manuscript containing the commentary of Kulluka. I have called this as the "vulgate version". It was Kulluka's version that has been translated repeatedly: Jones (1794), Burnell (1884), Buhler (1886) and Doniger (1991). (...)

The belief in the authenticity of Kulluka's text was openly articulated by Burnell (1884, xxix): "There is then no doubt that the textus receptus, viz., that of Kulluka Bhatta, as adopted in India and by European scholars, is very near on the whole to the original text." This is far from the truth. Indeed, one of the great surprises of my editorial work has been to discover how few of the over fifty manuscripts that I collated actually follow the vulgate in key readings.

— Patrick Olivelle, Manu's Code of Law (2005)[5]

Other scholars point to the inconsistencies and have questioned the authenticity of verses, and the extent to which verses were changed, inserted or interpolated into the original, at a later date. Sinha, for example, states that less than half, or only 1,214 of the 2,685 verses in Manusmriti, may be authentic.[62] Further, the verses are internally inconsistent.[63] Verses such as 3.55-3.62 of Manusmriti, for example, glorify the position of women, while verse such as 9.3 and 9.17 do the opposite.[62] Other passages found in Manusmriti, such as those relating to Ganesha, are modern era insertions and forgeries.[64] Robert E. Van Voorst states that the verses from 3.55-60 may be about respect given to a woman in her home, but within a strong patriarchal system.[65]

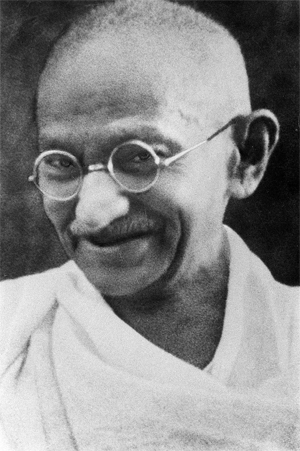

Nelson in 1887, in a legal brief before the Madras High Court of British India, had stated, "there are various contradictions and inconsistencies in the Manu Smriti itself, and that these contradictions would lead one to conclude that such a commentary did not lay down legal principles to be followed but were merely recommendatory in nature."[6] Mahatma Gandhi remarked on the observed inconsistencies within Manusmriti as follows,

I hold Manusmriti as part of Shastras. But that does not mean that I swear by every verse that is printed in the book described as Manusmriti. There are so many contradictions in the printed volume that, if you accept one part, you are bound to reject those parts that are wholly inconsistent with it. (...) Nobody is in possession of the original text.

— Mahatma Gandhi, An Adi-Dravida's Difficulties[66]

Commentaries

There are numerous classical commentaries on the Manusmṛti written in the medieval period.

Bhāruci is the oldest known commentator on the Manu Smṛti. Kane places him in the late 10th or early 11th century,[67] Olivelle places him in the 8th century,[68] and Derrett places him between 600-800 CE.[68][69] From these three opinions we can place Bhāruci anywhere from the early 7th century CE to the early 11th century CE. Bhāruci's commentary, titled Manu-sastra-vivarana, has far fewer number of verses than the Kullūka-Calcutta vulgate version in circulation since the British colonial era, and it refers to more ancient texts that are believed to be lost. It is also called Raja-Vimala, and J Duncan M Derrett states Bharuci was "occasionally more faithful to his source's historical intention" than other commentators.[70]

Medhātithi commentary on Manu Smṛti has been widely studied. Scholars such as Buhler, Kane, and Lingat believe he was from north India, likely the Kashmir region. His commentary on Manusmriti is estimated to be from 9th to 11th century.[71]

Govindarāja's commentary, titled Manutika, is an 11th-century commentary on Manusmriti, referred to by Jimutavahana and Laksmidhara, and was plagiarised by Kullūka, states Olivelle.[72]

Kullūka's commentary, titled Manvarthamuktavali, along with his version of the Manusmrti manuscript has been "vulgate" or default standard, most studied version, since it was discovered in 18th-century Calcutta by the British colonial officials.[72] It is the most reproduced and famous, not because, according to Olivelle, it is the oldest or because of its excellence, but because it was the lucky version found first.[72] The Kullūka commentary dated to be sometime between the 13th to 15th century, adds Olivelle, is mostly a plagiary of Govindaraja commentary from about the 11th century, but with Kullūka's criticism of Govindaraja.[72]

Nārāyana's commentary, titled Manvarthavivrtti, is probably from the 14th century and little is known about the author.[72] This commentary includes many variant readings, and Olivelle found it useful in preparing a critical edition of the Manusmriti text in 2005.[72]

Nandana was from south India, and his commentary, titled Nandini, provides a useful benchmark on Manusmriti version and its interpretation in the south.[72]

Other known medieval era commentaries on Manusmriti include those by Sarvajnanarayana, Raghavananda and Ramacandra.[72][73]

Significance and role in history

In ancient and medieval India

Scholars doubt Manusmriti was ever administered as law text in ancient or medieval Hindu society. David Buxbaum states, "in the opinion of the best contemporary orientalists, it [Manusmriti] does not, as a whole, represent a set of rules ever actually administered in Hindustan. It is in great part an ideal picture of that which, in the view of a Brahmin, ought to be law".[74]

Donald Davis writes, "there is no historical evidence for either an active propagation or implementation of Dharmasastra [Manusmriti] by a ruler or any state – as distinct from other forms of recognizing, respecting and using the text. Thinking of Dharmasastra as a legal code and of its authors as lawgivers is thus a serious misunderstanding of its history".[75] Other scholars have expressed the same view, based on epigraphical, archaeological and textual evidence from medieval Hindu kingdoms in Gujarat, Kerala and Tamil Nadu, while acknowledging that Manusmriti was influential to the South Asian history of law and was a theoretical resource.[76][77]