Richard Francis Burton [Mirza Abdullah the Bushri] [Hâjî Abdû El-Yezdî] [Frank Baker] by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/9/20

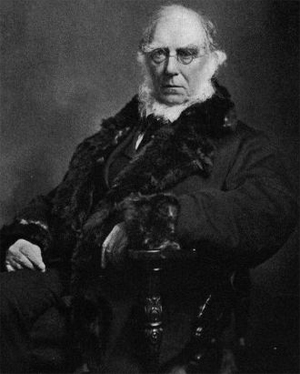

Sir Richard Francis Burton, KCMG FRGS

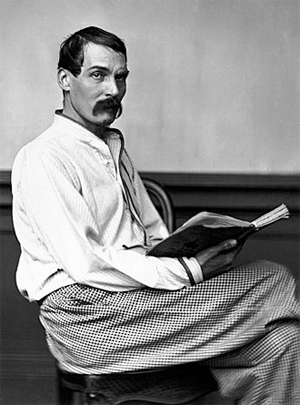

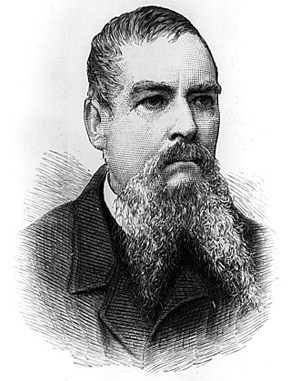

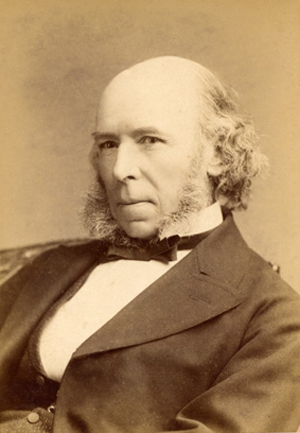

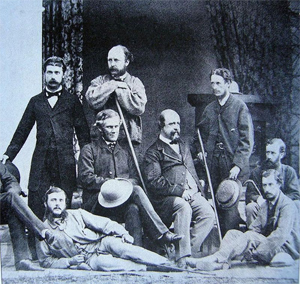

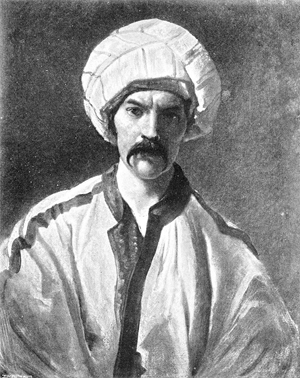

Burton in 1864

Born: 19 March 1821, Torquay, Devon, England

Died: 20 October 1890 (aged 69), Trieste, Austria-Hungary

Burial place: St Mary Magdalen Roman Catholic Church, Mortlake, London, England

Nationality: British

Other names: Mirza Abdullah the Bushri; Hâjî Abdû El-Yezdî; Frank Baker

Alma mater: Trinity College, Oxford

Occupation: Soldier, diplomat, explorer, translator, arabist, author

Notable work: Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al Madinah and Meccah; The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night; The Kasidah

Spouse(s): Isabel Arundell (m. 1861)

Military career

Nickname(s): Ruffian Dick

Allegiance: British Empire

Service/branch: Bombay Army

Years of service: 1842–1861

Rank: Captain

Battles/wars: Crimea War

Awards: Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George; Crimea Medal

Sir Richard Francis Burton KCMG FRGS (/ˈbɜːrtən/; 19 March 1821 – 20 October 1890) was a British explorer, geographer, translator, writer, soldier, orientalist, cartographer, ethnologist, spy,[1] linguist, poet, fencer, and diplomat. He was famed for his travels and explorations in Asia, Africa and the Americas, as well as his extraordinary knowledge of languages and cultures. According to one count, he spoke 29 European, Asian and African languages.[2]

Burton's best-known achievements include: a well-documented journey to Mecca in disguise, at a time when Europeans were forbidden access on pain of death; an unexpurgated translation of One Thousand and One Nights (commonly called The Arabian Nights in English after early translations of Antoine Galland's French version); the publication of the Kama Sutra in English; a translation of The Perfumed Garden, the Arab Kama Sutra; and a journey with John Hanning Speke as the first Europeans to visit the Great Lakes of Africa in search of the source of the Nile.

His works and letters extensively criticised colonial policies of the British Empire, even to the detriment of his career. Although he aborted his university studies, he became a prolific and erudite author and wrote numerous books and scholarly articles about subjects including human behaviour, travel, falconry, fencing, sexual practices, and ethnography. A characteristic feature of his books is the copious footnotes and appendices containing remarkable observations and information. William Henry Wilkins wrote: "So far as I can gather from all I have learned, the chief value of Burton’s version of The Scented Garden lay not so much in his translation of the text, though that of course was admirably done, as in the copious notes and explanations which he had gathered together for the purpose of annotating the book. He had made this subject a study of years. For the notes of the book alone he had been collecting material for thirty years, though his actual translation of it only took him eighteen months."[3]

Burton was a captain in the army of the East India Company, serving in India, and later briefly in the Crimean War. Following this, he was engaged by the Royal Geographical Society to explore the east coast of Africa, where he led an expedition guided by locals and was the first European known to have seen Lake Tanganyika. In later life, he served as British consul in Fernando Pó (now Bioko, Equatorial Guinea), Santos in Brazil, Damascus (Ottoman Syria), and finally in Trieste. He was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and was awarded a knighthood in 1886.[4]

Biography

Early life and education (1821–1841)Burton was born in Torquay, Devon, at 21:30 on 19 March 1821; in his autobiography, he incorrectly claimed to have been born in the family home at Barham House in Elstree in Hertfordshire.[5][6] He was baptized on 2 September 1821 at Elstree Church in Borehamwood, Hertfordshire.[7] His father, Lt.-Colonel Joseph Netterville Burton, of the 36th Regiment, was an Irish-born British army officer of Anglo-Irish extraction who through his mother's family—the Campbells of Tuam—was a first cousin of Lt.-Colonel Henry Peard Driscoll and Mrs Richard Graves. Richard's mother, Martha Baker, was the daughter and co-heiress of a wealthy English squire, Richard Baker (1762–1824), of Barham House, Hertfordshire, for whom he was named. Burton had two siblings, Maria Katherine Elizabeth Burton (who married Lt.-General Sir Henry William Stisted) and Edward Joseph Netterville Burton, born in 1823 and 1824, respectively.[8]

Burton's family travelled extensively during his childhood and employed various tutors to educate him. In 1825, they moved to Tours in France. In 1829, Burton began a formal education at a preparatory school in Richmond Green in Richmond, Surrey, run by Reverend Charles Delafosse.[9] Over the next few years, his family travelled between England, France, and Italy. Burton showed a talent to learn languages and quickly learned French, Italian, Neapolitan and Latin, as well as several dialects. During his youth, he allegedly had an affair with a Roma girl and learned the rudiments of the Romani language. The peregrinations of his youth may have encouraged Burton to regard himself as an outsider for much of his life. As he put it, "Do what thy manhood bids thee do, from none but self expect applause".[10]

Burton matriculated at Trinity College, Oxford, on 19 November 1840. Before getting a room at the college, he lived for a short time in the house of William Alexander Greenhill, then doctor at the Radcliffe Infirmary. Here, he met John Henry Newman, whose churchwarden was Greenhill. Despite his intelligence and ability, Burton was antagonised by his teachers and peers. During his first term, he is said to have challenged another student to a duel after the latter mocked Burton's moustache. Burton continued to gratify his love of languages by studying Arabic; he also spent his time learning falconry and fencing. In April 1842, he attended a steeplechase in deliberate violation of college rules and subsequently dared to tell the college authorities that students should be allowed to attend such events. Hoping to be merely "rusticated"—that is, suspended with the possibility of reinstatement, the punishment received by some less provocative students who had also visited the steeplechase—he was instead permanently expelled from Trinity College.[11]

According to Ed Rice, speaking on Burton's university days, "He stirred the bile of the dons by speaking real - that is, Roman-Latin instead of the artificial type peculiar to England, and he spoke Greek Romaically, with the accent of Athens, as he had learned it from a greek merchant at Marseilles, as well as the classical forms. Such a linguistic feat was a tribute to Burton's remarkable ear and memory, for he was only a teenager when he was in Italy and southern France.[12]

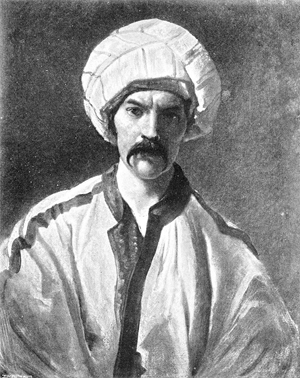

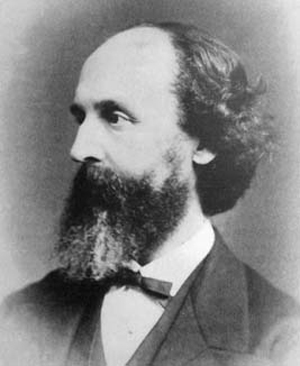

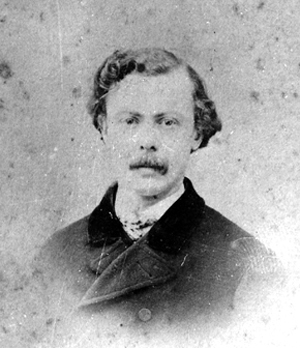

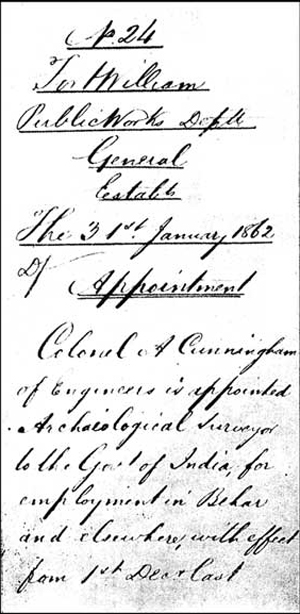

Army career (1842–1853) Burton in Persian disguise as "Mirza Abdullah the Bushri" (c. 1849–50)

Burton in Persian disguise as "Mirza Abdullah the Bushri" (c. 1849–50)In his own words, "fit for nothing but to be shot at for six pence a day",[13] Burton enlisted in the army of the East India Company at the behest of his ex-college classmates who were already members. He hoped to fight in the first Afghan war, but the conflict was over before he arrived in India. He was posted to the 18th Bombay Native Infantry based in Gujarat and under the command of General Charles James Napier.[14] While in India, he became a proficient speaker of Hindustani, Gujarati, Punjabi, Sindhi, Saraiki and Marathi as well as Persian and Arabic. His studies of Hindu culture had progressed to such an extent that "my Hindu teacher officially allowed me to wear the janeo (Brahmanical Thread)".[15] Him Chand, his gotra teacher, a Nagar Brahmin, could have been an apostate.[16] Burton's interest (and active participation) in the cultures and religions of India was considered peculiar by some of his fellow soldiers, who accused him of "going native" and called him "the White Nigger".[17] Burton did have many peculiar habits that set him apart from other soldiers. While in the army, he kept a large menagerie of tame monkeys in the hopes of learning their language, accumulating sixty "words".[18][12]:56–65 He also earned the name "Ruffian Dick"[12]:218 for his "demonic ferocity as a fighter and because he had fought in single combat more enemies than perhaps any other man of his time".[19]

According to Ed Rice, "Burton now regarded the seven years in India as time wasted." Yet, "He had already passed the official examinations in six languages and was studying two more and was eminently qualified." His religious experiences were varied, including attending Catholic services, becoming a Nāgar Brāhmins, adopting Sikhism, conversion to Islam, and undergoing chillá for Qadiri Sufism. Regarding Burton's Muslim beliefs, Ed Rice states, "Thus, he was circumcised, and made a Muslim, and lived like a Muslim and prayed and practiced like one." Furthermore, Burton, "...was entitled to call himself a hāfiz, one who can recite the Qur'ān from memory."[12]:58,67–68,104–108,150–155,161,164

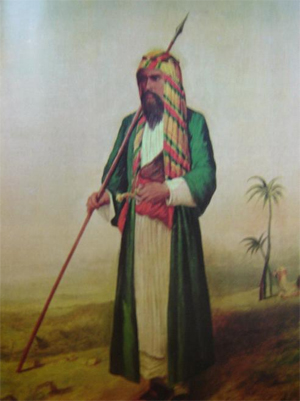

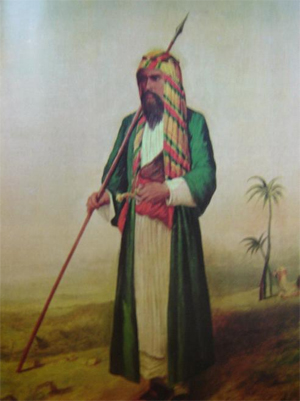

First explorations and journey to Mecca (1851–53) "The Pilgrim", illustration from Burton's Personal Narrative (Burton disguised as "Haji Abdullah", 1853)

"The Pilgrim", illustration from Burton's Personal Narrative (Burton disguised as "Haji Abdullah", 1853)Burton's pilgrimage to Medina and Mecca in 1853, was his realization of "the plans and hopes of many and many a year...to study thoroughly the inner life of the Moslem." Traveling through Alexandria in April, then Cairo in May, where he stayed in June during Ramadan, Burton first donned the guise of a Persian mirza, then a Sunnī "Shaykh, doctor, magician and dervish. Accompanied by an Indian boy slave called Nūr, Burton further equipped himself with a case for carrying the Qur'ān, but instead had three compartments for his watch and compass, money, and penknife, pencils, and numbered pieces of paper for taking notes. His diary he kept in a break pocket, unseen. Burton traveled onwards with a group of nomads to Suez, sailed to Yambu, and joined a caravan to Medina, where he arrived on 27 July, earning the title Zair. Departing Medina with the Damascus caravan on 31 August, Burton entered Mecca on 11 September. There, he participated in the Tawaf, traveled to Mount Arafat, and participated in the Stoning of the Devil, all the while taking notes on the Kaaba, its Black Stone, and the Zamzam Well. Departing Mecca, he journeyed to Jeddah, back to Cairo, returning to duty in Bombay. In India, Burton wrote his Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah. Of his journey, Burton wrote, "at Mecca there is nothing theatrical, nothing that suggests the opera, but all is simple and impressive...tending, I believe, after its fashion, to good."[12]:179–225

Motivated by his love of adventure, Burton got the approval of the Royal Geographical Society for an exploration of the area, and he gained permission from the board of directors of the East India Company to take leave from the army. His seven years in India gave Burton a familiarity with the customs and behaviour of Muslims and prepared him to attempt a Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca and, in this case, Medina). It was this journey, undertaken in 1853, which first made Burton famous. He had planned it whilst travelling disguised among the Muslims of Sindh, and had laboriously prepared for the adventure by study and practice (including undergoing the Muslim tradition of circumcision to further lower the risk of being discovered).[20]

Although Burton was certainly not the first non-Muslim European to make the Hajj (Ludovico di Varthema did this in 1503 and Johann Ludwig Burckhardt in 1815),[21] his pilgrimage is the most famous and the best documented of the time. He adopted various disguises including that of a Pashtun to account for any oddities in speech, but he still had to demonstrate an understanding of intricate Islamic traditions, and a familiarity with the minutiae of Eastern manners and etiquette. Burton's trek to Mecca was dangerous, and his caravan was attacked by bandits (a common experience at the time). As he put it, though "... neither Koran or Sultan enjoin the death of Jew or Christian intruding within the columns that note the sanctuary limits, nothing could save a European detected by the populace, or one who after pilgrimage declared himself an unbeliever".[22] The pilgrimage entitled him to the title of Hajji and to wear the green head wrap. Burton's own account of his journey is given in A Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah.[23][12]:179–225

Burton sat for the examination as an Arab linguist. The examiner was Robert Lambert Playfair, who disliked Burton. As Professor George Percy Badger knew Arabic well, Playfair asked Badger to oversee the exam. Having been told that Burton could be vindictive, and wishing to avoid any animosity should Burton fail, Badger declined. Playfair conducted the tests; despite Burton's success living as an Arab, Playfair had recommended to the committee that Burton be failed. Badger later told Burton that "After looking [Burton's test] over, I [had] sent them back to [Playfair] with a note eulogising your attainments and ... remarking on the absurdity of the Bombay Committee being made to judge your proficiency inasmuch as I did not believe that any of them possessed a tithe of the knowledge of Arabic you did."[24]

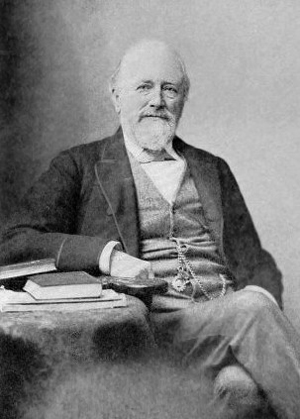

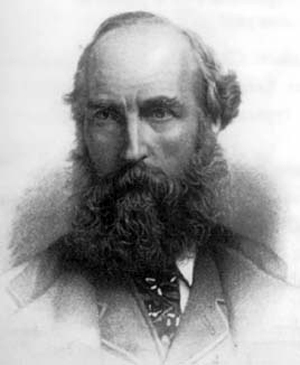

Early explorations (1854–55) Isabel Burton

Isabel BurtonIn May 1854, Burton traveled to Aden in preparation for his Somaliland Expedition, supported by the Royal Geographical Society. Other members included G.E. Herne, William Stroyan, and John Hanning Speke. Burton undertook the expedition to Harar, Speke investigated the Wady Nogal, while Herne and Stroyan stayed on at Berbera. According to Burton, "A tradition exists that with the entrance of the first [white] Christian Harar will fall." With Burton's entry, the "Guardian Spell" was broken.[12]:219–220,227–264

This Somaliland Expedition lasted from 29 October 1854 to 9 February 1855, with much of the time spent in the port of Zeila, where Burton was a guest of the town's Governor al-Haji Sharmakay bin Ali Salih. Burton, "assuming the disguise of an Arab merchant" called Haji Mirza Abdullah, awaited word that the road to Harar was safe. On 29 December, Burton met with Gerard Adan in the village of Sagharrah, when Burton openly proclaimed himself an English officer with a letter for the Amīr of Harar. On 3 January 1855, Burton made it to Harar, and was graciously met by the Amir. Burton stayed in the city for ten days, officially a guest of the Amir but in reality his prisoner. The journey back was plagued by lack of supplies, and Burton wrote that he would have died of thirst had he not seen desert birds and realized they would be near water. Burton made it back to Berbera on 31 January 1855.[25][12]:238–256

Following this adventure, Burton prepared to set out in search of the source of the Nile, accompanied by Lieutenant Speke, Lieutenant G. E. Herne and Lieutenant William Stroyan and a number of Africans employed as bearers. However, while the expedition was camped near Berbera, his party was attacked by a group of Somali waranle ("warriors") belonging to Isaaq clan. The officers estimated the number of attackers at 200. In the ensuing fight, Stroyan was killed and Speke was captured and wounded in eleven places before he managed to escape. Burton was impaled with a javelin, the point entering one cheek and exiting the other. This wound left a notable scar that can be easily seen on portraits and photographs. He was forced to make his escape with the weapon still transfixing his head. It was no surprise then that he found the Somalis to be a "fierce and turbulent race".[26] However, the failure of this expedition was viewed harshly by the authorities, and a two-year investigation was set up to determine to what extent Burton was culpable for this disaster. While he was largely cleared of any blame, this did not help his career. He describes the harrowing attack in First Footsteps in East Africa (1856).[27][12]:257–264

After recovering from his wounds in London, Burton traveled to Constantinople during the Crimean War, seeking a commission. He received one from General W.F. Beatson, as the Chief of Staff for "Beatson's Horse", popularly called the Bashi-bazouks, and based in Gallipoli. Burton returned after an incident which disgraced Beatson, and implicated Burton as the instigator of a "mutiny", damaging his reputation.[12]:265–271

Exploring the African Great Lakes (1856–1860)In 1856, the Royal Geographical Society funded another expedition for Burton and Speke, "and exploration of the then utterly unknown Lake regions of Central Africa." They would travel from Zanzibar to Ujiji along a caravan route established in 1825 by an Arab slave and ivory merchant. The Great Journey commenced on 5 June 1857 with their departure from Zanzibar, their caravan consisting of Baluchi mercenaries led by Ramji, 36 porters, eventually a total of 132 persons, all led by the caravan leader Said bin Salim. From the beginning, Burton and Speke were hindered by disease, malaria, fevers, and other maladies, at times both having to be carried in a hammock. Pack animals died, and natives deserted, taking supplies with them. Yet, on 7 November 1857, they made it to Kazeh, and departed for Ujij on 14 Dec. Speke wanted to head north, sure they would find the source of the Nile at what he later named Victoria Nyanza, but Burton persisted in heading west.[12]:273–297

Monument commemorating Burton and Speke's arrival in Ujiji

Monument commemorating Burton and Speke's arrival in UjijiThe expedition arrived at Lake Tanganyika on 13 February 1858. Burton was awestruck by the sight of the magnificent lake, but Speke, who had been temporarily blinded, was unable to see the body of water. By this point much of their surveying equipment was lost, ruined, or stolen, and they were unable to complete surveys of the area as well as they wished. Burton was again taken ill on the return journey; Speke continued exploring without him, making a journey to the north and eventually locating the great Lake Victoria, or Victoria Nyanza, on 3 August. Lacking supplies and proper instruments, Speke was unable to survey the area properly but was privately convinced that it was the long-sought source of the Nile. Burton's description of the journey is given in Lake Regions of Equatorial Africa (1860). Speke gave his own account in The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863).[28][12]:298–312,491–492,500

Burton and Speke made it back to Zanzibar on 4 March 1859, and left on 22 March for Aden. Speke immediately boarded HMS Furious for London, where he gave lectures, and was awarded a second expedition by the Society. Burton arrived London on 21 May, discovering "My companion now stood forth in his new colours, and angry rival." Speke additionally published What Led to the Discovery of the Source of the Nile (1863), while Burton's Zanzibar; City, Island, and Coast was eventually published in 1872.[12]:307,311–315,491–492,500

Burton then departed on a trip to the United States in April 1860, eventually making it to Salt Lake City on 25 August. There he studied Mormonism and met Brigham Young. Burton departed San Francisco on 15 November, for the voyage back to England, where he published The City of the Saints and Across the Rocky Mountains to California.[12]:332–339,492

Burton and Speke"Burton and Speke" redirects here. For the novel by William Harrison, see Burton and Speke (novel).

Burton was the first European to see Lake Tanganyika

Burton was the first European to see Lake TanganyikaA prolonged public quarrel followed, damaging the reputations of both Burton and Speke. Some biographers have suggested that friends of Speke (particularly Laurence Oliphant) had initially stirred up trouble between the two.[29] Burton's sympathizers contend that Speke resented Burton's leadership role. Tim Jeal, who has accessed Speke's personal papers, suggests that it was more likely the other way around, Burton being jealous and resentful of Speke's determination and success. "As the years went by, [Burton] would neglect no opportunity to deride and undermine Speke's geographical theories and achievements".[30]

Speke had earlier proven his mettle by trekking through the mountains of Tibet, but Burton regarded him as inferior as he did not speak any Arabic or African languages. Despite his fascination with non-European cultures, some have portrayed Burton as an unabashed imperialist convinced of the historical and intellectual superiority of the white race, citing his involvement in the Anthropological Society, an organization that established a doctrine of scientific racism.[31][32] Speke appears to have been kinder and less intrusive to the Africans they encountered, and reportedly fell in love with an African woman on a future expedition.[33]

The two men travelled home separately. Speke returned to London first and presented a lecture at the Royal Geographical Society, claiming Lake Victoria as the source of the Nile. According to Burton, Speke broke an agreement they had made to give their first public speech together. Apart from Burton's word, there is no proof that such an agreement existed, and most modern researchers doubt that it did. Tim Jeal, evaluating the written evidence, says the odds are "heavily against Speke having made a pledge to his former leader".[34]

Speke undertook a second expedition, along with Captain James Grant and Sidi Mubarak Bombay, to prove that Lake Victoria was the true source of the Nile. Speke, in light of the issues he was having with Burton, had Grant sign a statement saying, among other things, "I renounce all my rights to publishing ... my own account [of the expedition] until approved of by Captain Speke or [the Royal Geographical Society]".[35]

On 16 September 1864, Burton and Speke were scheduled to debate the source of the Nile at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. On the day before the debate, Burton and Speke sat near each other in the lecture hall. According to Burton's wife, Speke stood up, said "I can't stand this any longer," and abruptly left the hall. That afternoon Speke went hunting on the nearby estate of a relative. He was discovered lying near a stone wall, felled by a fatal gunshot wound from his hunting shotgun. Burton learned of Speke's death the following day while waiting for their debate to begin. A jury ruled Speke's death an accident. An obituary surmised that Speke, while climbing over the wall, had carelessly pulled the gun after himself with the muzzle pointing at his chest and shot himself. Alexander Maitland, Speke's only biographer, concurs.[36]

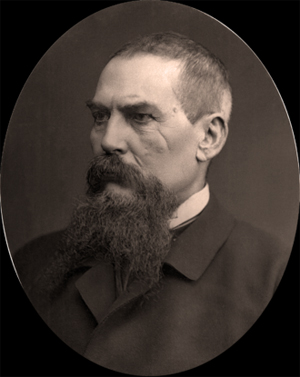

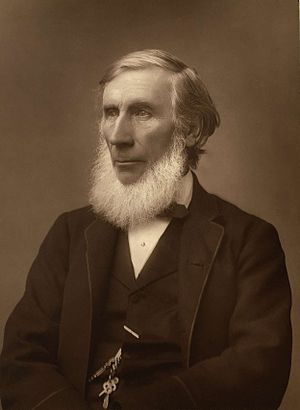

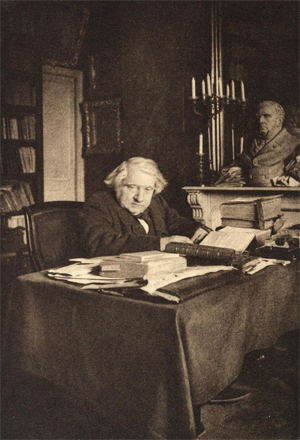

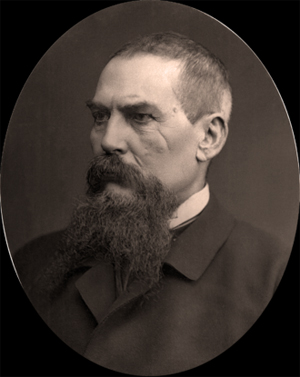

Diplomatic service and scholarship (1861–1890) Burton in 1876

Burton in 1876On 22 January 1861, Burton and Isabel married in a quiet Catholic ceremony although he did not adopt the Catholic faith at this time. Shortly after this, the couple were forced to spend some time apart when he formally entered the Diplomatic Service as consul on the island of Fernando Po, now Bioko in Equatorial Guinea. This was not a prestigious appointment; because the climate was considered extremely unhealthy for Europeans, Isabel could not accompany him. Burton spent much of this time exploring the coast of West Africa, documenting his findings in Abeokuta and The Cameroons Mountains: An Exploration (1863), and A Mission to Gelele, King of Dahome (1864). He described some of his experiences, including a trip up the Congo River to the Yellala Falls and beyond, in his 1876 book Two trips to gorilla land and the cataracts of the Congo.[37][12]:349–381,492–493

The couple were reunited in 1865 when Burton was transferred to Santos in Brazil. Once there, Burton travelled through Brazil's central highlands, canoeing down the São Francisco River from its source to the falls of Paulo Afonso.[38] He documented his experiences in The Highlands of Brazil (1869).[12]:

In 1868 and 1869 he made two visits to the war zone of the Paraguayan War, which he described in his Letters from the Battlefields of Paraguay (1870).[39]

In 1868 he was appointed as the British consul in Damascus, an ideal post for someone with Burton's knowledge of the region and customs.[40] According to Ed Rice, "England wanted to know what was going on in the Levant," another chapter in The Great Game. Yet, the Turkish governor Mohammed Rashid 'Ali Pasha, feared anti-Turkish activities, and was opposed to Burton's assignment.[12]:395–399,402,409

In Damascus, Burton made friends with Abdelkader al-Jazairi, while Isabel befriended Jane Digby, calling her "my most intimate friend." Burton also met with Charles Francis Tyrwhitt-Drake and Edward Henry Palmer, collaborating with Drake in writing Unexplored Syria (1872).[12]:402–410,492

However, the area was in some turmoil at the time with considerable tensions between the Christian, Jewish and Muslim populations. Burton did his best to keep the peace and resolve the situation, but this sometimes led him into trouble. On one occasion, he claims to have escaped an attack by hundreds of armed horsemen and camel riders sent by Mohammed Rashid Pasha, the Governor of Syria. He wrote, "I have never been so flattered in my life than to think it would take three hundred men to kill me."[41] Burton eventually suffered the enmity of the Greek Christian and Jewish communities. Then, his involvement with the Sházlis, a group of Muslims Burton called "Secret Christians longing for baptism," which Isabel called "his ruin." He was recalled in August 1871, prompting him to telegram Isabel "I am recalled. Pay, pack, and follow at convenience."[12]:412–415

Burton was reassigned in 1872 to the sleepy port city of Trieste in Austria-Hungary.[42][dead link] A "broken man", Burton was never particularly content with this post, but it required little work, was far less dangerous than Damascus (as well as less exciting), and allowed him the freedom to write and travel.[43]

In 1863 Burton co-founded the Anthropological Society of London with

Dr. James Hunt. In Burton's own words, the main aim of the society (through the publication of the periodical Anthropologia) was "to supply travellers with an organ that would rescue their observations from the outer darkness of manuscript and print their curious information on social and sexual matters". On 13 February 1886, Burton was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (KCMG) by Queen Victoria.[44]

He wrote a number of travel books in this period that were not particularly well received. His best-known contributions to literature were those considered risqué or even pornographic at the time, which were published under the auspices of the Kama Shastra society. These books include The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana (1883) (popularly known as the Kama Sutra), The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885) (popularly known as The Arabian Nights), The Perfumed Garden of the Shaykh Nefzawi (1886) and The Supplemental Nights to the Thousand Nights and a Night (seventeen volumes 1886–98).

Published in this period but composed on his return journey from Mecca, The Kasidah[10] has been cited as evidence of Burton's status as a Bektashi Sufi. Deliberately presented by Burton as a translation, the poem and his notes and commentary on it contain layers of Sufic meaning that seem to have been designed to project Sufi teaching in the West.[45] "Do what thy manhood bids thee do/ from none but self expect applause;/ He noblest lives and noblest dies/ who makes and keeps his self-made laws" is The Kasidah's most-quoted passage. As well as references to many themes from Classical Western myths, the poem contains many laments that are accented with fleeting imagery such as repeated comparisons to "the tinkling of the Camel bell" that becomes inaudible as the animal vanishes in the darkness of the desert.[46]

Other works of note include a collection of Hindu tales, Vikram and the Vampire (1870); and his uncompleted history of swordsmanship, The Book of the Sword (1884). He also translated The Lusiads, the Portuguese national epic by Luís de Camões, in 1880 and, the next year, wrote a sympathetic biography of the poet and adventurer. The book The Jew, the Gipsy and el Islam was published posthumously in 1898 and was controversial for its criticism of Jews and for its assertion of the existence of Jewish human sacrifices. (Burton's investigations into this had provoked hostility from the Jewish population in Damascus (see the Damascus affair). The manuscript of the book included an appendix discussing the topic in more detail, but by the decision of his widow, it was not included in the book when published).[citation needed]

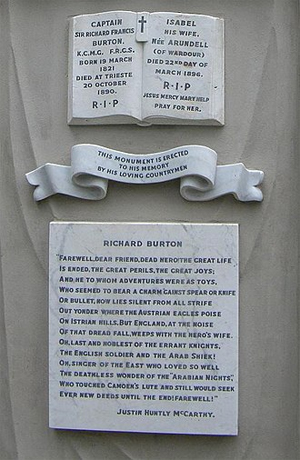

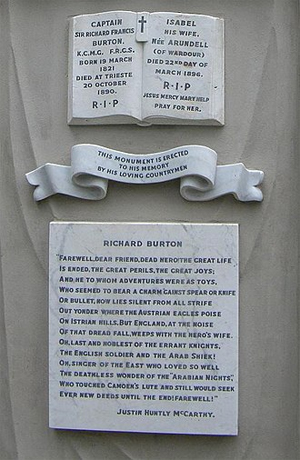

Death Richard Burton's Tomb at Mortlake, south west London, June 2011.

Richard Burton's Tomb at Mortlake, south west London, June 2011. Close up of inscription on the tomb.

Close up of inscription on the tomb.Burton died in Trieste early on the morning of 20 October 1890 of a heart attack. His wife Isabel persuaded a priest to perform the last rites, although Burton was not a Catholic and this action later caused a rift between Isabel and some of Burton's friends. It has been suggested that the death occurred very late on 19 October and that Burton was already dead by the time the last rites were administered. On his religious views, Burton called himself an atheist, stating he was raised in the Church of England which he said was "officially (his) church".[47]

Isabel never recovered from the loss. After his death she burned many of her husband's papers, including journals and a planned new translation of The Perfumed Garden to be called The Scented Garden, for which she had been offered six thousand guineas and which she regarded as his "magnum opus". She believed she was acting to protect her husband's reputation, and that she had been instructed to burn the manuscript of The Scented Garden by his spirit, but her actions have been widely condemned.[48]

Isabel wrote a biography in praise of her husband.[49]

The couple are buried in a remarkable tomb in the shape of a Bedouin tent, designed by Isabel,[50] in the cemetery of St Mary Magdalen Roman Catholic Church Mortlake in southwest London. The coffins of Sir Richard and Lady Burton can be seen through a window at the rear of the tent, which can be accessed via a short fixed ladder. Next to the lady chapel in the church there is a memorial stained-glass window to Burton, also erected by Isabel; it depicts Burton as a medieval knight.[51] Burton's personal effects and a collection of paintings, photographs and objects relating to him are in the Burton Collection at Orleans House Gallery, Twickenham.[52]

Kama Shastra SocietyBurton had long had an interest in sexuality and some erotic literature. However, the Obscene Publications Act of 1857 had resulted in many jail sentences for publishers, with prosecutions being brought by the Society for the Suppression of Vice. Burton referred to the society and those who shared its views as Mrs Grundy. A way around this was the private circulation of books amongst the members of a society. For this reason Burton, together with Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot, created the Kama Shastra Society to print and circulate books that would be illegal to publish in public.[53]

One of the most celebrated of all his books is his translation of The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (commonly called The Arabian Nights in English after early translations of Antoine Galland's French version) in ten volumes (1885), with seven further volumes being added later. The volumes were printed by the Kama Shastra Society in a subscribers-only edition of one thousand with a guarantee that there would never be a larger printing of the books in this form. The stories collected were often sexual in content and were considered pornography at the time of publication. In particular, the Terminal Essay in volume 10 of the Nights contained a 14,000-word essay entitled "Pederasty" (Volume 10, section IV, D), at the time a synonym for homosexuality (as it still is, in modern French). This was and remained for many years the longest and most explicit discussion of homosexuality in any language. Burton speculated that male homosexuality was prevalent in an area of the southern latitudes named by him the "Sotadic zone".[54]

Perhaps Burton's best-known book is his translation of The Kama Sutra. It is untrue that he was the translator since the original manuscript was in ancient Sanskrit, which he could not read. However, he collaborated with Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot on the work and provided translations from other manuscripts of later translations. The Kama Shastra Society first printed the book in 1883 and numerous editions of the Burton translation are in print to this day.[53]

His English translation from a French edition of the Arabic erotic guide The Perfumed Garden was printed as The Perfumed Garden of the Cheikh Nefzaoui: A Manual of Arabian Erotology (1886). After Burton's death, Isabel burnt many of his papers, including a manuscript of a subsequent translation, The Scented Garden, containing the final chapter of the work, on pederasty. Burton all along intended for this translation to be published after his death, to provide an income for his widow.[55]

Burton's languagesBy the end of his life, Burton had mastered at least 26 languages – or 40, if distinct dialects are counted.[56]

1. English

2. French

3. Occitan (Gascon/Béarnese dialect)

4. Italian

a. Neapolitan Italian

5. Romani

6. Latin

7. Greek

8. Saraiki

9. Hindustani

a. Urdu

b. Sindhi

10. Marathi

11. Arabic

12. Persian (Farsi)

13. Pushtu

14. Sanskrit

15. Portuguese

16. Spanish

17. German

18. Icelandic

19. Swahili

20. Amharic

21. Fan

22. Egba

23. Asante

24. Hebrew

25. Aramaic

26. Many other West African & Indian dialects

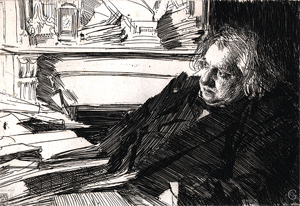

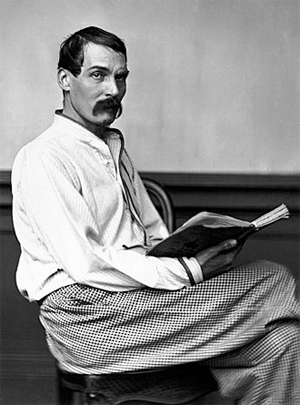

Scandals Burton in later life

Burton in later lifeBurton's writings are unusually open and frank about his interest in sex and sexuality. His travel writing is often full of details about the sexual lives of the inhabitants of areas he travelled through. Burton's interest in sexuality led him to make measurements of the lengths of the penises of male inhabitants of various regions, which he includes in his travel books. He also describes sexual techniques common in the regions he visited, often hinting that he had participated, hence breaking both sexual and racial taboos of his day. Many people at the time considered the Kama Shastra Society and the books it published scandalous.[57]

Biographers disagree on whether or not Burton ever experienced homosexual sex (he never directly acknowledges it in his writing). Allegations began in his army days when Charles James Napier requested that Burton go undercover to investigate a male brothel reputed to be frequented by British soldiers. It has been suggested that Burton's detailed report on the workings of the brothel led some to believe he had been a customer.[58] There is no documentary evidence that such a report was written or submitted, nor that Napier ordered such research by Burton, and it has been argued that this is one of Burton's embellishments.[59]

A story that haunted Burton up to his death (recounted in some of his obituaries) was that he came close to being discovered one night when he lifted his robe to urinate rather than squatting as an Arab would. It was said that he was seen by an Arab and, in order to avoid exposure, killed him. Burton denied this, pointing out that killing the boy would almost certainly have led to his being discovered as an impostor. Burton became so tired of denying this accusation that he took to baiting his accusers, although he was said to enjoy the notoriety and even once laughingly claimed to have done it.[60][61] A doctor once asked him: "How do you feel when you have killed a man?", Burton retorted: "Quite jolly, what about you?". When asked by a priest about the same incident Burton is said to have replied: "Sir, I'm proud to say I have committed every sin in the Decalogue."[62] Stanley Lane-Poole, a Burton detractor, reported that Burton "confessed rather shamefacedly that he had never killed anybody at any time."[61]

These allegations coupled with Burton's often irascible nature were said to have harmed his career and may explain why he was not promoted further, either in army life or in the diplomatic service. As an obituary described: "...he was ill fitted to run in official harness, and he had a Byronic love of shocking people, of telling tales against himself that had no foundation in fact."[63] Ouida reported: "Men at the FO [Foreign Office] ... used to hint dark horrors about Burton, and certainly justly or unjustly he was disliked, feared and suspected ... not for what he had done, but for what he was believed capable of doing."[64]

Sotadic Zone Burton's Sotadic Zone encompassed only small areas of Europe and North Africa, larger areas of Asia, and all of North and South America.

Burton's Sotadic Zone encompassed only small areas of Europe and North Africa, larger areas of Asia, and all of North and South America.The existence of a Sotadic Zone was a hypothesis of Burton. He asserted that there exists a geographic zone in which pederasty (romantic-sexual intimacy between a boy and a man) is prevalent and celebrated among the indigenous inhabitants.[65] The name derives from Sotades, a 3rd-century BC Greek poet who was the chief representative of a group of writers of obscene, and sometimes pederastic, satirical poetry; these homoerotic verses are preserved in the Greek Anthology, a collection of poems spanning the Classical and Byzantine periods of Greek literature.

Burton first advanced his Sotadic Zone concept in the "Terminal Essay"[66] contained in Volume 10 of his translation of The Arabian Nights, which he called The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night, in 1886.[67]

ExtentAccording to Burton's description,

1. the Sotadic Zone is bounded westward by the northern shores of the Mediterranean (N. Lat. 43 °) and by the southern (N. Lat. 30°). Thus the depth would be 780 to 800 miles including meridional France, the Iberian peninsula, Italy and Greece, with the coast-regions of Africa from Morocco to Egypt;

2. Running eastward the Sotadic Zone narrows, embracing Asia Minor, Mesopotamia and Chaldaea, Afghanistan, Sindh, the Punjab and Kashmir.

3. In Indo-China the belt begins to broaden, enfolding China, Japan and Turkistan.

4. It then embraces the South Sea Islands and the New World where, at the time of its discovery, Sotadic love was, with some exceptions, an established racial institution.

5. "Within the Sotadic Zone the Vice is popular and endemic, held at the worst to be a mere peccadillo, whilst the races to the North and South of the limits here defined practise it only sporadically amid the opprobrium of their fellows who, as a rule, are physically incapable of performing the operation and look upon it with the liveliest disgust."

In popular culture

Fiction• In the short story "The Aleph" (1945) by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges, a manuscript by Burton is discovered in a library. The manuscript contains a description of a mirror in which the whole universe is reflected.

• The Riverworld series of science fiction novels (1971–83) by Philip José Farmer has a fictional and resurrected Burton as a primary character.

• William Harrison's Burton and Speke is a 1984 novel about the two friends/rivals.[68]

• The World Is Made of Glass: A Novel by Morris West[69] tells the story of Magda Liliane Kardoss von Gamsfeld in consultation with Carl Gustav Jung; Burton is mentioned on pp. 254–7 and again on p. 392.

• Der Weltensammler[70] by Iliya Troyanov is a fictional reconstruction of three periods of Burton's life, focusing on his time in India, his pilgrimage to Medina and Mecca, and his explorations with Speke.

• Burton is the main character in the "Burton and Swinburne" steampunk series by Mark Hodder (2010–2015): The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack; The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man; Expedition to the Mountains of the Moon; The Secret of Abdu El Yezdi; The Return of the Discontinued Man; and The Rise of the Automated Aristocrats. These novels depict an alternate world where Queen Victoria was killed early in her reign due to the inadvertent actions of a time-traveler acting as Spring-Heeled Jack, with a complex constitutional revision making Albert King in her place.

• Though not one of the primary characters in the series, Burton plays an important historical role in the Area 51 series of books by Bob Mayer (written under the pen name Robert Doherty).

• Burton and his partner Speke are recurrently mentioned in one of Jules Verne's Voyages Extraordinaires, the 1863 novel Five Weeks in a Balloon, as the voyages of Kennedy and Ferguson are attempting to link their expeditions with those of Heinrich Barth in west Africa.

• In the novel The Bookman's Promise (2004) by John Dunning, the protagonist buys a signed copy of a rare Burton book, and from there Burton and his work are major elements of the story. A section of the novel also fictionalizes a portion of Burton's life in the form of recollections of one of the characters.

Drama• In the BBC production of The Search for the Nile series (1972), Burton is portrayed by actor Kenneth Haigh.

• The film Mountains of the Moon (1990) (starring Patrick Bergin as Burton) relates the story of the Burton-Speke exploration and subsequent controversy over the source of the Nile. The script was based on Harrison's novel.

• In the Canadian film Zero Patience (1993), Burton is portrayed by John Robinson as having had "an unfortunate encounter" with the Fountain of Youth and is living in present-day Toronto. Upon discovering the ghost of the famous Patient Zero, Burton attempts to exhibit the finding at his Hall of Contagion at the Museum of Natural History.

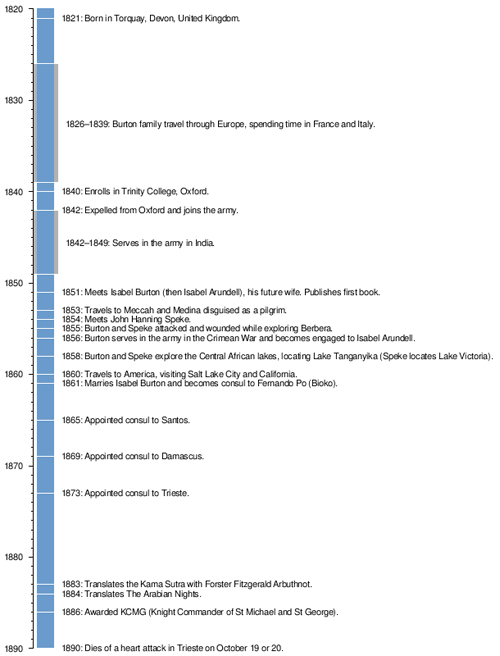

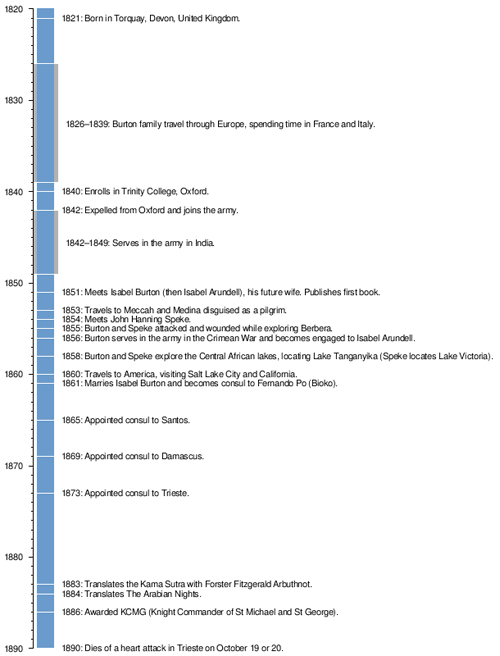

Chronology Timeline of Richard Francis Burton's life (1821–1890)Works and correspondence

Timeline of Richard Francis Burton's life (1821–1890)Works and correspondenceMain article: Richard Francis Burton bibliography

Burton published over 40 books and countless articles, monographs and letters. A great number of his journal and magazine pieces have never been catalogued. Over 200 of these have been collected in PDF facsimile format at burtoniana.org.[71]

An extensive selection of Burton's correspondence can be found in the four-volume Book of Burtoniana edited by Gavan Tredoux (burtoniana.org, 2016), which is freely downloadable in HTML, PDF, Kindle/MOBI and ePub formats.[72]

Brief selections from a variety of Burton's writings are available in Frank McLynn's Of No Country: An Anthology of Richard Burton (1990; New York: Charles Scribner's Sons).

See also• Selim Aga

• Mausoleum of Sir Richard and Lady Burton

• List of polyglots

References1. Lovell, p. xvii.

2. Young, S. (2006). "India". Richard Francis Burton: Explorer, Scholar, Spy. New York: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 16–26. ISBN 9780761422228.

3. Burton, I.; Wilkins, W. H. (1897). The Romance of Isabel Lady Burton. The Story of Her Life. New York: Dodd Mead & Company. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

4. "Historic Figures: Sir Richard Burton". BBC. Retrieved 7 April 2017

5. Lovell, p. 1.

6. Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 37 Archived 8 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

7. Page, William (1908). A History of the County of Hertford. Constable. vol. 2, pp. 349–351. ISBN 978-0-7129-0475-9.

8. Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 38 Archived 8 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

9. Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 52 Archived 8 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

10. Burton, R. F. (1911). "Chapter VIII". The Kasîdah of Hâjî Abdû El-Yezdî (Eight ed.). Portland: Thomas B. Mosher. pp. 44–51.

11. Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 81 Archived 8 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

12. Rice, Ed (1990). Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: the secret agent who made the pilgrimage to Mecca, discovered the Kama Sutra, and brought the Arabian nights to the West. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 22. ISBN 978-0684191379.

13. Falconry in the Valley of the Indus, Richard F. Burton (John Van Voorst 1852) page 93.

14. Ghose, Indira (January 2006). "Imperial Player: Richard Burton in Sindh". In Youngs, Tim (ed.). Travel Writing in the Nineteenth Century. Anthem Press. pp. 71–86. doi:10.7135/upo9781843317692.005. ISBN 9781843317692. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

15. Burton (1893), Vol. 1, p. 123.

16. Rice, Edward. Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton (1991). p. 83.

17. In 1852, a letter from Burton was published in The Zoist: "Remarks upon a form of Sub-mesmerism, popularly called Electro-Biology, now practised in Scinde and other Eastern Countries", The Zoist: A Journal of Cerebral Physiology & Mesmerism, and Their Applications to Human Welfare, Vol.10, No.38, (July 1852), pp.177–181.

18. Lovell, p. 58.

19. Wright (1906), vol. 1, pp. 119–120 Archived 8 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

20. Seigel, Jerrold (1 December 2015). Between Cultures: Europe and Its Others in Five Exemplary Lives. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812247619 – via Google Books.

21. Leigh Rayment. "Ludovico di Varthema". Discoverers Web. Discoverers Web. Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

22. Selected Papers on Anthropology, Travel, and Exploration by Richard Burton, edited by Norman M. Penzer (London, A. M. Philpot 1924) p. 30.

23. Burton, R. F. (1855). A Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah. London: Tylston and Edwards.

24. Lovell, pp. 156–157.

25. Burton, R., Speke, J. H., Barker, W. C. (1856). First footsteps in East Africa or, An Exploration of Harar. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

26. In last of a series of dispatches from Mogadishu, Daniel Howden reports on the artists fighting to keep a tradition alive, The Independent, dated Thursday, 2 December 2010.

27. Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. pp. 449–458.

28. Speke, John Hanning. "The Journal of the Discovery of the Source of the Nile".

http://www.wollamshram.ca. Retrieved 19 July2020.

29. Carnochan, pp. 77–78 cites Isabel Burton and Alexander Maitland

30. Jeal, p. 121.

31. Jeal, p. 322.

32. Kennedy, p. 135.

33. Jeal, pp. 129, 156–166.

34. Jeal, p. 111.

35. Lovell, p. 341.

36. Kennedy, p. 123.

37. Richard Francis Burton, Two Trips to Gorilla Land and the Cataracts of the Congo, 2 vols. (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low & Searle, 1876).

38. Wright (1906), vol. 1, p. 200 Archived 8 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

39. Letters from the Battlefields of Paraguay, the Preface.

40. "No. 23447". The London Gazette. 4 December 1868. p. 6460.

41. Burton (1893), Vol. 1, p. 517.

42. "No. 23889". The London Gazette. 20 September 1872. p. 4075.

43. Wright, Thomas (1 January 1906). The Life of Sir Richard Burton. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 9781465550132 – via Google Books.

44. "No. 25559". The London Gazette. 16 February 1886. p. 743.

45. The Sufis by Idries Shah (1964) p. 249ff

46. The Kasidah of Haji Abdu El-Yezdi. 1880.

47. Wright (1906) "Some three months before Sir Richard's death," writes Mr. P. P. Cautley, the Vice-Consul at Trieste, to me, "I was seated at Sir Richard's tea table with our clergy man, and the talk turning on religion, Sir Richard declared, 'I am an atheist, but I was brought up in the Church of England, and that is officially my church.'"

48. Wright (1906), vol. 2, pp. 252–254 Archived 29 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

49. Burton (1893)

50. Cherry, B.; Pevsner, N. (1983). The Buildings of England – London 2: South. London: Penguin Books. p. 513. ISBN 978-0140710472.

51. Boyes, Valerie & Wintersinger, Natascha (2014). Encountering the Uncharted and Back – Three Explorers: Ball, Vancouver and Burton. Museum of Richmond. pp. 9–10.

52. De Novellis, Mark. "More about Richmond upon Thames Borough Art Collection". Art UK. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

53. Ben Grant, "Translating/'The' “Kama Sutra”", Third World Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 3, Connecting Cultures (2005), 509–516

54. Pagan Press (1982–2012). "Sir Richard Francis Burton Explorer of the Sotadic Zone". Pagan Press. Pagan Press. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

55. The Romance of Lady Isabel Burton (chapter 38) Archived 10 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine by Isabel Burton (1897) (URL accessed 12 June 2006)

56. McLynn, Frank (1990), Of No Country: An Anthology of the Works of Sir Richard Burton, Scribner's, pp. 5–6.

57. Kennedy, D. (2009). The highly civilized man: Richard Burton and the Victorian world. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674025523. OCLC 647823711.

58. Burton, Sir Richard (1991) Kama Sutra, Park Street Press, ISBN 0-89281-441-1, p. 14.

59. Godsall, pp. 47–48.

60. Lovell, pp. 185–186.

61. Rice, Edward (2001) [1990]. Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: A Biography. Da Capo Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0306810282.

62. Brodie, Fawn M. (1967). The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton, W.W. Norton & Company Inc.: New York 1967, p. 3.

63. Obituary in Athenaeum No. 3287, 25 October 1890, p. 547.

64. Richard Burton by Ouida, article appearing in the Fortnightly Review June (1906) quoted by Lovell

65. Waitt, Gordon; Kevin Markwell (2008). "The Lure of the "Sotadic Zone"'". Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide. 15 (2).

66. (§1., D)

67. The Book of the Thousand Nights and A Night. s.l.: Burton Society (Private printing). 1886.

68. William Harrison, Burton and Speke (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1984), ISBN 978-0-312-10873-1.

69. (Coronet Books, 1984), ISBN 0-340-34710-4.

70. 2006, translated as The Collector of Worlds [2008].

71. "Shorter Works by Richard Francis Burton".

72. "The Book of Burtoniana, in Four Volumes, edited by Gavan Tredoux".

Sources

Books and articles• Cust, R.N. (1895). "Sir Richard Burton". Linguistic and oriental essays: written from the year 1861 to 1895. London: Trübner & Co. pp. 80–82.

• Brodie, Fawn M. (1967). The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-907871-23-1.

• Burton, Isabel (1893). The Life of Captain Sir Richard F. Burton KCMG, FRGS. Vols. 1 and 2. London: Chapman and Hall.

• Carnochan, W.B. (2006). The Sad Story of Burton, Speke, and the Nile; or, Was John Hanning Speke a Cad: Looking at the Evidence. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-8047-5325-8.

• Kennedy, Dane (2005). The Highly Civilized Man: Richard Burton and the Victorian World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01862-4.

• Edwardes, Allen (1963). Death Rides a Camel. New York: The Julian Press.

• Farwell, Byron (1963). Burton: A Biography of Sir Richard Francis Burton. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-012068-4.

• Godsall, Jon R (2008). The Tangled Web – A life of Sir Richard Burton. London: Matador Books. ISBN 978-1906510-428.

• Hitchman, Francis (1887), Richard F. Burton, K.C.M.G.: His Early, Private and Public Life with an Account of his Travels and Explorations, Two volumes; London: Sampson and Low.

• Jeal, Tim (2011). Explorers of the Nile: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Great Victorian Adventure. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-300-14935-7.

• Lovell, Mary S. (1998). A Rage to Live: A Biography of Richard & Isabel Burton. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04672-4.

• McDow, Thomas F. 'Trafficking in Persianness: Richard Burton between mimicry and similitude in the Indian Ocean and Persianate worlds'. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 30.3 (2010): 491–511. ISSN 1089-201X

• McLynn, Frank (1991). From the Sierras to the Pampas: Richard Burton's Travels in the Americas, 1860–69. London: Century. ISBN 978-0-7126-3789-3.

• McLynn, Frank (1993). Burton: Snow on the Desert. London: John Murray Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7195-4818-5.

• Newman, James L. (2009), Paths without Glory: Richard Francis Burton in Africa, Potomac Books, Dulles, Virginia; ISBN 978-1-59797-287-1.

• Moorehead, Alan (1960). The White Nile. New York: Harper & Row. p. 448. ISBN 978-0-06-095639-4.

• Ondaatje, Christopher (1998). Journey to the Source of the Nile. Toronto: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-200019-2.

• Ondaatje, Christopher (1996). Sindh Revisited: A Journey in the Footsteps of Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton. Toronto: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-1-59048-221-6.

• Rice, Edward (1990). Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: The Secret Agent Who Made the Pilgrimage to Makkah, Discovered the Kama Sutra, and Brought the Arabian Nights to the West. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

• Seigel, Jerrold (2016). Between Cultures: Europe and Its Others in Five Exemplary Lives. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4761-9.

• Sparrow-Niang, Jane (2014). Bath and the Nile Explorers: In commemoration of the 150th anniversary of Burton and Speke's encounter in Bath, September 1864, and their 'Nile Duel' which never happened. Bath: Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution. ISBN 978-0-9544941-6-2

• Wisnicki, Adrian S. (2008). "Cartographical Quandaries: The Limits of Knowledge Production in Burton's and Speke's Search for the Source of the Nile". History in Africa. 35: 455–79. doi:10.1353/hia.0.0001.

• Wisnicki, Adrian S. (2009). "Charting the Frontier: Indigenous Geography, Arab-Nyamwezi Caravans, and the East African Expedition of 1856–59". Victorian Studies 51.1 (Aut.): 103–37.

• Wright, Thomas (1906). The Life of Sir Richard Burton. Vols. 1 and 2. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-1-4264-1455-8. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

Film documentaries• Search for the Nile, 1971 BBC mini-series featuring Kenneth Haigh as Burton

• In The Victorian Sex Explorer, Rupert Everett documents Burton's travels. Part of the Channel Four (UK) 'Victorian Passions' season. First Broadcast on 9 June 2008.

External links• Complete Works of Richard Burton at burtoniana.org. Includes over 200 of Burton's journal and magazine pieces.

• Works by Sir Richard Francis Burton at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Richard Francis Burton at Internet Archive

• Works by Richard Francis Burton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

• "Archival material relating to Richard Francis Burton". UK National Archives. – index to world holdings of Burton archival materials

• The Penetration of Arabia by David George Hogarth (1904) – discusses Burton in the second section, "The Successors"

• Capt Sir Richard Burton Museum (sirrichardburtonmuseum.co.uk), "located in a private residence in central St Ives, Cornwall UK"

• Sir Richard Francis Burton at Library of Congress Authorities, with 172 catalogue records