God's Body, or, The Lingam Made Flesh: Conflicts over the Representation of the Sexual Body of the Hindu God Shivaby Wendy Doniger

Vol. 78, No. 2, The Body and the State: How the State Controls and Protects the Body, Part I, pp. 485-508 (24 pages), Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press

(SUMMER 2011)

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Until February, 2010, The Encyclopedia Britannica entry on Hinduism included this sentence about the Hindu god Shiva:

In temples and in private shrines, Shiva is . .. worshipped in the form of the lingam, or phallus, often embedded in the yoni, the symbol of the female sexual organ.

That definition was based on the one established by the standard, nineteenth-century Sanskrit dictionary of Sir Monier Monier-Williams. which defines the lingam (or linga -- the "m" is optional) as "the male organ or Phallus (esp. that of Siva worshipped in the form of a stone or marble column which generally rises out of a yoni, q.v., and is set up in temples dedicated to Siva)" (see figure 1).1 [An earlier and rather different version of this essay was presented as the 2010 Presidential Lecture at the Art Institute of Chicago, November 11, 2010. I am indebted to James Cuno, Madhuvanti Ghosh, and Mary Sue Glosser for their valuable input on that occasion.] But in February of 2010, in response to a number of complaints from Hindu readers, Britannica replaced its original sentence with the following rather cumbersome paragraph:

In temples and in private shrines, Shiva is worshipped in the form of the lingam, a cylindrical votary object that is often embedded in a yoni, or spouted dish. Together they symbolize the eternal process of creation and regeneration. Since the late 19th century, some scholars have interpreted the lingam and yoni as being aniconic representations of the male and female sexual organs, respectively.

This change was a response to a dispute about the symbolism of the lingam that has been going on for many centuries: Is its primary meaning inexorably tied to the physical body (iconic), or is it abstract (aniconic)? The Britannica hedged.2 [In the interest of full disclosure I must confess that I serve on the Britannica's International Board of Editors, and that the Britannica staff consulted me in making this revision.]

The Shiva-lingam is well known throughout India, a signifier that is understood across barriers of caste and language, a linga franca, if you will. But what is signified? Many Hindus have, like Sigmund Freud, seen lingams in every naturally occurring elongated object, including the so-called self-created lingams, objets trouves such as stalagmites. But recently, many Hindus, especially bloggers on the Hindu Internet (sometimes called the Hindernet), have insisted that the lingam has nothing at all to do with any part of the body of any human or any god, and the Britannica acted in response to that groundswell, or, rather, airswell. Where did this argument come from?

In this article I will attempt to answer this question about present-day Hindu sensibilities with a consideration of the history of the usages of the word lingam in ancient texts and the evidence of material images of the Shiva-lingam in Indian art, as well as the historical role of two non-Hindu stales in India -- Muslim and British -- in the formation of contemporary attitudes to the lingam.

Figure 1. Lingam in yoni with flower offerings. Patan, Nepal (2007). Courtesy Charles S. Preston.

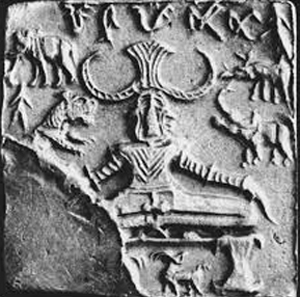

Figure 1. Lingam in yoni with flower offerings. Patan, Nepal (2007). Courtesy Charles S. Preston. Figure 2. "Pashupati" Seal (Seal 420), Mohenjo-Daro, Indus Valley Civilization. Courtesy of imagesofasia.com. Seal held at the National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi. Originally printed in John Huber Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization (1931).THE INDUS VALLEY

Figure 2. "Pashupati" Seal (Seal 420), Mohenjo-Daro, Indus Valley Civilization. Courtesy of imagesofasia.com. Seal held at the National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi. Originally printed in John Huber Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization (1931).THE INDUS VALLEYThe story begins in the Indus Valley civilization in what is now northwest India and Pakistan,

a culture (dating from well before 2500 BCE) with rich archeological remains but no deciphered script. The textual silence has allowed scholars to draw wild conclusions, often politically motivated, about the nature of the many physical objects discovered there. Some people have seen a kind of proto-lingam on one of the many carved stones found there, rectangular sections of soapstone about the size of a postage stamp, which were used as seals or stamps.

Sir John Marshall began it all. Biach. Bramma and Vichnou, accompanied by a numerous cortege of Brammes, were formerly on the mountain Keilassan to visit Chib [Siva]. They found him enjoying his wife. Their arrival did not urge him to stop. He saw them, but without saying a word to them, or giving them the slightest courtesy, due to the fury of his passion, and inflamed by the drunkenness into which he was plunged, had knocked him out of himself, and he was no longer capable of shame or modesty. At this sight, some of those who made up this illustrious assembly, among others, Vishnu, only laughed, and felt ashamed for him. Others, outraged with annoyance and anger, testified to all their indignation, and charged him with insults. "No, you are only a demon," they said to him, "and even worse than a demon, who gives everything to passion. You wear the face, and you have the game, since you are not even susceptible to shame in the presence of such an illustrious assembly." All equally unworthy [finally] held the same language, and entered into the same sentiments. "The friendship we had for him," they all said unanimously, "had taken us to his house to pay him a visit, and we only find in him a man completely devoted to passion and drunkenness, who takes no notice of us, and who continues his infamies even in our presence. Therefore, no virtuous man, from now on, has any trade with him, and those who frequent him will be regarded as fools, and as men unworthy of any society with honest people." Having said this, they all withdrew, each at soy.

Chib, a short time later, having returned to himself, asked his guards who were those who had come to his house. "It is Bramma and Vishnou," they said to him, "accompanied by a numerous troop of penitents; but seeing you in this state, they loaded you with curses and insults and withdrew." These words were like a thunderbolt which penetrated to the heart of Chib and Dourgua. They both died, and died in the same posture they had been in until then. Chib wanted this action which had made him experience shame to be celebrated by men. This is how he expressed it: "Shame made me die, but it gave me a new figure, and this new figure is the Lingam. You, demons, my subjects, look at it therefore as another means itself. It is indeed a part of it. Moreover, I want all men to offer their sacrifices to Lingam. Those who honor me under this figure will surely get the object of [all] their wishes and a place in the Veikuntam. I am the supreme being. My Lingam is too. Therefore, to render it the honors of the divinity is a work of virtue, and you could not do anything more useful, nothing more meritorious. The tree of Marmélle is, of all trees, the one I love the most. If they want to please me, they must offer me the flowers, the leaves, and the fruits. Hear more what I have to add. Those who will fast on January 14th in honor of the Lingam, and who the following night will offer it the sacrifice, will present it with leaves from the Marmelle tree, and will ensure a place in the Keilassan. Listen again, demons. If you have any desire to become virtuous, learn what are the fruits that should be derived from the honors that will be paid to Lingam. Those who make it out of earth and sacrifice to it, will receive their reward. Those who make it out of stone, will merit seven times more, and will never see the gates of hell. Those who make it with silver will deserve seven times more, and with gold, seven times more. My ministers, go and teach this truth to men, and urge them to embrace it."

Indeed, they did, and all peoples were instructed. Some have adopted it and are offering their sacrifices to the Lingam today. Others did not want to add foy to it, and did not consider it. Others, finally, have regarded it as an infamy, and refused to hear about it. For me, I have known for a long time, and I am fully convinced, that the Lingam is Chïb himself, and therefore the supreme being. So I am going to design the figure as I traced it to men to give them an idea. I told them that this Lingam was whitish in color, that he had 3 eyes, 5 faces, and that he liked to cover himself with tiger skin; that he was before the world, that he was the principle of the world, that he dispels our fears, and always grants us the object of all our wishes. Bramma himself offered him sacrifices in Keilassan. The Brames, the penitents, the Kings, the merchants, the Choutres, recognize no other god than Chib. He alone receives their homage and their wishes. I have just given you a short summary of the history of Lingam, and of what gave rise to it, and how his cult spread. Tell me now what you think. I don't know of anyone more enlightened than you. Therefore continue to remove my doubts, and destroy my errors, in order to save me.

Chumantou. What you just said is the crowning achievement of everything you have already said. No matter how much I think and dream, I don't know how to go about making you reasonable, and make you recognize the monstrous errors in which I see you plunged. A man who has given in to passing errors, but who does not have a completely corrupt heart, is still capable of tasting reason, and clinging to the truth as soon as it is shown to him. But he who has both a corrupt mind and heart are quite incapable of it. It is therefore impossible to make him know the truth, even less to make him love. It is with him, as with dry wood, that you can break it, but you cannot make it bend. You first said that Chib was the supreme being, [but] how, after all you have just said about him, can it even occur to you? One would regard the world as vile and despicable, if the supreme being would give himself up to women until he could no longer part with them. Such is the character that you make him have. Such a name and such behavior cannot therefore suit him that we regard as the supreme being, and that we adore as our god. God is essentially happy. He is sovereign. He can therefore desire nothing outside of himself, and all that is external to him can in no way contribute to his happiness or his felicity. Indeed, when you give Chib the name of being supreme, you represent him to us immersed in drunkenness, and delivering everything to a woman whom he enjoyed without interruption. If he was, in fact, the supreme being, we should see men who depend on him, like his creatures, let themselves be inflamed with anger, and make him bear its effects. Is it possible that you did not feel [all] the indecency of such conduct? Don't you see what's going on in front of your eyes? If a Roy makes a mistake, we would see a slave going to load him with insults and curses. Learn from this that the God whom one recognizes as master, and who is in fact above the anger of men, does not have to bear the weight or feel the effects of his actions. You add that Bochisto and the other penitents offered the Lingam their homage, and honored him like a deity. What does this prove? That they have both been as perverted, as corrupt, as toy, and nothing more? The most virtuous men desire only to possess God, and only after death are we are allowed to see him and enjoy him. Chib's house is always full of demons. His suite is made up of them. The demons must therefore enjoy a privilege which is not granted to even the most virtuous. God has no body. Chib certainly has one, and his pleasure is to cover himself with a tiger skin. God does not desire anything outside of Himself. All of Chib's mind, heart and attention, is on a woman. How can you confuse the two and give them the same name? God, by an act of his will, created the world, so we [all] give him the name of father, and recognize him as such. It is only Kartiko and Gonecho who give this name to Chib, and who recognize being his children. You have said on other occasions that Bramma and Vishnu were enlightened and virtuous men. But if they were indeed, would they curse someone who must be regarded as the supreme being? Would they throw curses at him? To see God, to enjoy him, is the reward of virtue. It is the height of happiness. Seeing and hanging out with Chib is a crime, because all you see in him is a shameless monster. You say that Chib, at the time of death, remained under the figure of Lingam. You are wrong at first to put him to death, since God is eternal and does not die. But besides, there was no more decent figure in the world which could better suit the divinity. You are going to tell these fables to an ignorant people who are hardly able to distinguish their left hand from their right hand. But lacking even in light, can you carry deceit and wickedness to this point? You are not ignorant of what is excellent in God's nature, and know, above all, that he cannot be transformed into what is most base. You are not unaware, either, that one should offer the sacrifice only to the being who is above all. How then, unhappy that you are, can you resolve to engage the people to honor by this act of religion what is most despicable and most base? The lingam is the shameful part of the body. All men hide it out of modesty. And you, unhappy man, you carry infamy to the point of urging them to offer it their sacrifices, and to pay it the honors which are only due to the divinity. What use is it to instruct you in the truth? To what end are all the pains that I take upon myself, since you are still capable of such infamies and such abominations? If you want me to continue to instruct you, leave therefore, forever, such a monstrous error. No matter how much I tell you, I foresee that you will do nothing. A spirit spoiled by impurity feeds only on impure ideas, and must, in fact, make gods of this species. A heart completely corrupted, surrendered to sin, must consequently offer its incense to base and contemptible objects, and nothing should appear to him to be more worthy of it than that which serves as an instrument of pleasure. I will not, however, stop telling you that Bramma is not a God, that Vishnu is not a God, that Indro is not a God, nor all the others to whom you lavish this name, and that Chib, finally, is not a God, still less the Lingam.

-- Ezourvedam: A French Veda of the Eighteenth Century, Edited with an Introduction by Ludo Rocher

In 1931, in his magisterial three-volume publication, Mohenjo Daro and the Indus Civilization, which devotes five pages of a long chapter entitled, "Religion," to Seal 420: "There appears at Mohenjo-daro a male god, who is recognizable at once as a prototype of the historic Siva .... The lower limbs are bare and the phallus (urdhva-medhra) seemingly exposed, but it is possible that what appears to be the phallus is in reality the end of the waistband" (Marshall 1931: 52-56) (see figure 2). Urdhva-medhra ("upward phallus") is a Sanskrit term for an erect phallus, like the Greek-based English term "ithy-phallic." The mute image on the seal suggested to Marshall an early form of the Hindu god Shiva, because both Shiva and the figure on the seal are seated in a possibly yogic posture and have horns, multiple faces, surrounding animals, and an erect phallus. Marshall's suggestion was taken up by several generations of scholars, who made much of this tiny bit of soapstone; the millimeter of the putative erection on this seal (the whole seal is barely an inch high) has, like the optional inch of Cleopatra's nose, caused a great deal of historical fuss. The upward-phallus- or-is-it-perhaps-just-his-waistband-or-the-knot-in-his-dhoti? has a lineage in Indian art history that comes to rival the snake-or-is-it-perhaps-just-a-rope? in Indian philosophical idealism, as a trope for the power of illusion. And there is a general resemblance between this image and later Hindu images of Shiva. The Indus people may well have created a symbolism of the divine phallus. But even if this is so, and we cannot know it, it does not mean that the Indus images are the source of the Hindu images, or that they had the same meaning.

The Vedas and the UpanishadsThe word

lingam does not occur in the Rig Veda (RV), the most ancient Hindu text (c. 1500 BCE), nor does the god Shiva. But the deity Rudra, in many ways an antecedent of Shiva, does make a brief appearance, and the male organ, by another name (

kaprith, perhaps meaning "expanding" or "extending pleasure"), also appears in the Veda, in an obscene hymn about a sexual competition between a male monkey and the god Indra (RV 10.86.16-17; Doniger O'Flaherty 1981: 257-63). (The term also occurs at Rig Veda 10.101.12; Doniger O'Flaherty 1981: 66-67.) Indra is a virile god, a distant cousin of Zeus and Jupiter, who bequeaths to Shiva some aspects of his mythology, including myths of castration (Doniger O'Flaherty 1973, 85-86, 130-135). The male organ also appears, by yet another name (

shishna, "piercer" or "tail"), in two Vedic hymns imploring that same god, Indra, to strike down "those whose god is the phallus" or "those who play with the phallus" (shishna-devas) (RV 7.21.5, 10.99.3). Some scholars have suggested that this phrase may refer to an "early Indus cult" of the lingam (Hopkins 1971:9-10). But there is no evidence that the Indus Valley people had such a cult, let alone that the people who composed the Rig Veda knew about it, or that they disapproved of it instead of assimilating it to their own worship of their own phallic god, Indra -- no lawyer would go into court with such shaky evidence.

The word

lingam appears in the Upanishads (mystical texts from around 600 BCE) only in its general sense of a sign, as smoke is a sign of fire. But the male organ does appear, under still yet another name, in one of the oldest Upanishads, which calls it "the Thing" (

artha) (BA 6.4.11). The same text also describes the female organ in considerable detail, analogizing the Vedic oblation of butter into the fire to the act of sexual procreation (BA 6.2.13, 6.4.3). The worshipper in a sexual embrace with his wife imagines each part of the act as a part of the ritual of the oblation, while presumably anyone making the offering into the fire could also imagine each action as its sexual parallel. This is a very early instance of the interpretation of human sexual matters in terms of nonsexual, sacred matters (or, if you prefer, the reverse).

The MahabharataGradually the word

lingam took on the more particular meaning of a sign of gender, then the sign of the male gender, and finally the sign of the male gender of the god Shiva. In the Mahabharata, the ancient Sanskrit epic (c. 300 BCE to 300 CE), we first encounter the word

lingam unequivocally designating the sexual organ of Shiva:3 [Shiva in this text is called Harikesha (the Tawny-Haired), the Lord of the Mountain, the Eldest, the Lord Rudra, Bhava, and the Guru of the World; I have simplified the text by calling him Shiva throughout, and I have also condensed it somewhat, but added nothing.]

The creator, Brahma, wishing to create creatures, said to Shiva, the first being, "Create creatures, without delay." Shiva said, "Yes," but seeing that all creatures were flawed, he who had great ascetic heat plunged into the water and generated ascetic heat. Brahma waited for him for a very long time and then created another creator, a Prajapati ("lord of creatures"). The Prajapati, seeing Shiva submerged in the water, said to his father, Brahma, "I will create creatures, if there is no one who has been born before me." His father said to him, "There is no other male (purusha) born before you. This is just a pillar (or, Shiva who is called The Pillar) submerged in the water. Rest assured, and do the deed." And so the Prajapati created creatures. They were hungry and tried to eat the Prajapati, until Brahma provided them with food, plants, and animals, and then they began to procreate and increased in number.

Then Shiva stood up from the water. When he saw those creatures of various forms, increasing by themselves, he became angry, and he tore off his own lingam and threw it down on the ground, where it stood up just as it was. Brahma said to him, hoping to conciliate him with words, "What did you accomplish by staying so long in the water? And why did you tear out this lingam and plant it in the ground?" Then Shiva, becoming truly furious, said to Brahma, "Since someone else created these creatures, what will I do with it? The creatures can go on recycling forever, eating the food that I obtained for them through my ascetic heat." And Shiva went to his place on the mountain, to generate ascetic heat (M 10.17.10-26 [parentheses added]; see also Doniger O'Flaherty 1973: 131).

The "flaw" in the creatures seems to be their need for food, though later retellings say that Shiva hoped to produce, through his ascetic heat, creatures who would never die; to that degree, his powerful asceticism makes him more, not less, creative. What is significant for our question here is the ambiguity of the word for pillar (

sthanu): it is a name of Shiva, signifying the immobile, ascetic, desexualized form of the

lingam: but it also designates an inanimate pillar, which is what Brahma implies in his answer to the Prajapati, not exactly lying but drawing on the wrong meaning of the word in order to avoid admitting that there is, in fact, already another creator at work, precisely what the Prajapati did not want. Shiva in this myth is both a potentially procreative phallus (a fertile

lingam) and a pillar-like renouncer of sexuality (an ascetic

lingam). The word

lingam has the same double edge as the word "Pillar."

The Gudimallam Lingam Figure 3. The Gudimallam Lingam. Locaoted at the Parashurameshvara Temple in Gudimallam, Andhra Pradesh, circa 2nd-1st century BCE. Courtesy of Dr. Vandana Sinha, Director (Academic), Center for Art and Archaeology, American Institute of Indian Studies.

Figure 3. The Gudimallam Lingam. Locaoted at the Parashurameshvara Temple in Gudimallam, Andhra Pradesh, circa 2nd-1st century BCE. Courtesy of Dr. Vandana Sinha, Director (Academic), Center for Art and Archaeology, American Institute of Indian Studies.A

lingam (see figure 3) that scholars generally regard as the earliest physical depiction of the god Shiva was made sometime between the third and first centuries BCE in Gudimallam in southeastern Andhra Pradesh. Its anatomical detail is highly naturalistic (apart from its size: just under five feet high), and on the shaft is carved the figure of Shiva, also naturalistic, two-armed, holding an axe in one hand and the body of a small antelope in the other. His thin garment reveals his own sexual organ (not erect), his hair is matted, he wears large earrings, and he stands upon a dwarf. The details of its carving define this image unequivocally as a iconic representation of the male sexual organ; the hypothesis that it is a form of the god Shiva is suggested by the iconography of the axe, antelope, matted hair, and dwarf, and supported by the three horizontal lines, the sign of Shiva, that were painted on it some time after its original creation. Visitors to the Gudimallam

lingam in the early twenty-first century noted that while the large

lingam as a whole remains entirely naked, with all its anatomical detail, a chaste cloth was wrapped around the small image of the naked Shiva on the front of the

lingam, a kind of loincloth (or fig leaf) simultaneously covering up the middle of the figure in the middle of the

lingam and the middle of the

lingam itself. Here is a tradition driving with one foot on the accelerator and the other on the brake.

Stories about Shiva-Lingams in Later Sanskrit TextsThere is convincing textual evidence that people in ancient India associated the iconic form of the

lingam with the male sexual organ. A verse from the "Garland of Games" of Kshemendra, a Brahmin who lived in Kashmir in the elventh century CE, refers to the human counterpart of the divine Shival

lingam: "Having locked up the house on the pretext of venerating the

lingam, Randy scratches her itch with a

lingam of skin" (Narmamala 3.44). The first

lingam in this verse is certainly Shiva's, and there is an implied parallelism, if not identity, between it and the second one, which could be either a leather dildo (of which a number are described in the Kama-sutra, the great third-century CE Indian textbook of eroticism (KS 5.6.2-5, 7.2.4-13]) or its human prototype.

The human and divine levels of the

lingam were explicitly compared in a rather different way in a Sanskrit text that argued that all creatures in the universe are marked with the signs of the god Shiva and his consort, since all females have

pindis (the term for the base in which the sculpted form of the

lingam is set) and join with males, who have

lingams (like the Shiva-lingam set in the pindi) (SP 1.8.18-19; Doniger 2000: 397). In a sixteenth-century Marathi text, the Kali Yuga (the embodied spirit of the present Dark and Evil Age) grasps by one hand his

lingam (representing unrestrained sexuality, a synecdoche for wrong action of all kinds) and by the other hand his tongue (symbolic of lascivious speech), and he says, "I will be defeated only by those who guard this

lingam and their tongue."4 [Verse 2.82 of the Gurucaritra of Sarasvati Gangadhara, c. 1550 CE, composed in Marathi Ovi verse in Ganagapura, a partially marathi-speaking area of Northern Karnataka, Gulbarga district. I am indebted to Jeremy Morse for this text and translation.] The nineteenth-century sage Ramakrishna used to worship his own male organ because, he said, it reminded him of the Shiva-lingam; he had learned this "jivantalingapuja," or worship of the living

lingam, from his guru (Kripal 1995: 159-163).

The many Sanskrit myths that explain the origin of the worship of the Shiva-lingam can be divided into those that do regard the

lingam as part of the god's sexual anatomy and those that do not. Of the texts in which the

lingam is obviously the phallus of Shiva, like the myth about the Pillar that we have already considered, some -- most, but not all, told by worshippers of Shiva -- regard the

lingam as an entirely glorious form in which Shiva appears and accepts worship. But other texts -- some, but not all, told by worshippers of gods other than Shiva, particularly Vishnu -- regard the

lingam as an object of scorn and shame (Doniger O'Flaherty 1975: 137-53; 1990: 85-87). These texts are early evidence of the discomfort caused by the phallic meaning of the symbol, though they do not yet attempt to deny that meaning.

That discomfort can be traced back to ascetic and renunciant traditions that began in the Upanishads, alongside the very passages that praised the sexual act as inherently sacred. And this ascetic strain, often misogynist, often expressing a deep anxiety about the human body, challenged the other sort of Hinduism, the one that gloried in the body both for its fertility and for its eroticism. The two traditions remain in tension to this day.

The stories of Shiva in the Pine Forest occur in two sets of variants along this divide. In both sets, Shiva enters the Pine Forest naked, often "with his seed drawn up" ("upward seed," a variant of "upward-phallus"), either in order for his seed

not to fall down in the act of procreating, or in order to procreate, or both at once -- another striking instance of the sort of ambiguity that haunts this debate. The women of the Pine Forest fall madly in love with him, which infuriates their husbands, and Shiva's

lingam falls to the ground. But sometimes it falls as a result of the sages' curse (when the text regards the

lingam as shameful), and sometimes through Shiva's own volition (when the text regards the

lingam as a source of desirable power). In both cases, dire consequences follow, and the sages, having learned their lesson, agree to worship the Shiva-lingam forever after (Doniger O'Flaherty 1973: 172-209; 1990: 87-91; Shulman 2004).

Lingam-worship is cast in a definitely negative vein in a group of stories in which the sage Bhrigu visits the gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva in turn; the first two welcome the sage, but Shiva happens to be alone with his wife and refuses to be disturbed. The furious sage curses Shiva to be worshipped in the form of the thing that he seems to care most about, the lingam (PP 6.282.20-36; Doniger O'Flaherty 1973: 305-6). But

lingam-worship is a positive factor, and Shiva is superior, rather than inferior, to Brahma and Vishnu, in another myth in which the

lingam does not seem to have anything at all to do with any part of the male anatomy. In this myth, usually called "the ephiphany of the

lingam" (lingodbhava), Shiva appears in the form of a pillar in the water, the form that he takes in the Mahabharata story of self-castration, and indeed this episode of the epiphany is often told as a direct sequence to that story of self-castration (Doniger O'Flaherty 1973: 130-32). While Brahma and Vishnu are arguing as to which of them fathered the other, Shiva appears before them as a pillar of light and flame, infinitely high and infinitely deep. The two gods try in vain to find its top and bottom, Brahma in the form of a goose and Vishnu in the form of an aquatic boar, and sometimes Brahma lies and says he's found the top when he hasn't, for which he is cursed never to be worshipped in India any more (see figure 4). Then Brahma and Vishnu humbly protrate themselves before Shiva, recognizing that he had created both of them, as well as everything else in the universe (Brahmanda Purana 1.2.26.10-61; Doniger O'Flaherty 85-87). There is nothing sexual about this

lingam, though it is perhaps significant that it is the star witness in a debate about fatherhood.

Figure 4. Mudiyanur Lingodbhavamurti. The statue clearly illustrates Shiva in the center of his lingam of fire, Brahma as a goose on the top right, and Vishnu as a boar on the bottom left. The statue is from Mudiyanur, Tamilnadu, circa 12th century. Presently located at the Chennai Government Museum. Courtesy of Dr. Vandana Sinha, Director (Academic), Center for Art and Archaeology, American Institute of Indian Studies.The Lingam in Vernacular Texts

Figure 4. Mudiyanur Lingodbhavamurti. The statue clearly illustrates Shiva in the center of his lingam of fire, Brahma as a goose on the top right, and Vishnu as a boar on the bottom left. The statue is from Mudiyanur, Tamilnadu, circa 12th century. Presently located at the Chennai Government Museum. Courtesy of Dr. Vandana Sinha, Director (Academic), Center for Art and Archaeology, American Institute of Indian Studies.The Lingam in Vernacular TextsLater Sanskrit and vernacular texts depict the Shiva-lingam alternatively, and in combination, as a part of his body and as an abstract symbol of the god, worshipped with offerings of fruits and flowers. Hindus for many centuries have seen their god simultaneously in two forms: the true form of god is without any qualities (nir-guna), unimaginable; but out of compassion for us, and so that we can love him, the god also manifests himself in a form with qualities (sa-guna), perhaps as a human with two arms, or with particular features (a blue skin for Krishna, a third eye for Shiva). Each is real in its own way; sometimes you reach for one, sometimes for the other. In this way, too, many Hindus have regarded the

lingam as both abstract, without (sexual) qualities, and particular, with (sexual) qualities.

The lingam can also be real, and human, and particular, without being sexual. A number of South Indian texts in Tamil tell of a miracle: a stone image of Shiva, with a face, bleeds in response to, or to test, the devotion of a pious worshipper. Some versions of this story refer to this image simply as "the Lord," that is, Shiva, but other versions assume that what is meant is a statue of the Lord, a lingam. The many representations of this episode in both paintings and sculpture depict the form of a Shiva-lingam with a face and eyes. Such an image seems to be assumed, but never named as such, in this story about Shiva told in the Periya Puranam, a popular South Indian Tamil text from the twelfth century:

One day, Kannappar, the chief of a tribe of hunters, found Shiva in the jungle. Filled with love for the god and pity that he seemed to be all alone, Kannappar resolved to feed Shiva. He kicked aside the flowers that a Brahmin priest had left on the head of Shiva and gave him the flowers that he had worn on his own head. His feet, and his dogs' paws, left their marks on Shiva. He stayed with him all night, and left at dawn to hunt again.

In order to demonstrated to the Brahmin priest the greatness of Kannappar's love, Shiva caused blood to flow from one of his eyes. To staunch the flow, Kannappar gouged out his own eye with an arrow and replaced the god's eye with his. When Shiva made his second eye bleed, Kannappar put his foot on Shiva's eye to guide his hand, and he was about to pluck out his remaining eye when Shiva stretched out his hand to stop him, and placed Kannappar at his right hand (Periya Puranam 16; McGlashan 2006: 71-86).

Since at least the seventeenth century, the common Tamil term for Shiva's

lingam has been

kuRi (mark, or sign), a direct translation of the original, nonsexual meaning of

lingam. (An-kuRi and peN-kuRi -- "male sign" and "female sign" represent the Sanskrit

pum-lingam and

stri-lingam). The term kuRi is still common today as a respectable or medical term for the sign of sex. But this text never uses the term

lingam (or KuRi) at all, merely saying,

"The eyes of the Lord were bleeding." Nevertheless, many scholars subsume the Kannappar story under the category of bleeding

lingams (Ferro-Luzzi 1987; Cox 2005), and

the Tamil tradition assumes that the stone has the form of a lingam. Yet that stone has nothing to do with any part of Shiva's body but his eyes. (Of course, Freud would have something to say about the upward displacement of the genitals to the eyes, as in the blinding of Oedipus -- standing in for his castration -- but we need not follow there.)

THE MUSLIMSThe lingam took on a new role in Hinduism after Muslim rule began in the eleventh century CE. Many great temples were built at this time, but one large and influential twelfth-century South Indian Hindu sect differed from earlier renouncers in spurning not only houses but stone temples. These were the Lingayats ("People of the Lingam"), also called "Wanderers" because they prided themselves on being moving temples, itinerant, never putting down roots (Ramanujan 1974). Their founder preached a simplified devotion; no goal but to be united, at death, with Shiva, and no worship but that of a small lingam worn around the neck (Flood 1996: 171). This lingam was never said to have any sexual connotations: instead, the entire body of the worshipper represented the earthly body of the god, as the temple did for more conventional Hindus.

But several of the Delhi sultans, those who were particularly devout and iconoclast Muslims, regarded the lingam as sexual and anthropomorphic, and took pride in destroying as many lingams as they could.

In 1026, Mahmud of Ghazni attacked the temple of Somnath, which held a famous Shiva lingam: this much, at least, seems to be historical fact. But then comes the mythologizing. According to some versions of the story, including early Turko-Persian triumphalist sources, Mahmud stripped the great gilded lingam of its gold and hacked it to bits with his sword, sending the bits back to Ghazni, where they were incorporated into the steps of the new mosque (Keay 2000: 207-209). Medieval Hindu epics of resistance created a countermythology in which the stolen image came to life (another bit of evidence that it was regarded as a living thing, a body in itself) and eventually, like a horse trotting back to the stable, returned to the temple to be reconsecrated (Davis 1997: 90-112). Other sources, including local Sanskrit inscriptions, biographies of kings and merchants of the period, court epics, and popular narratives that have survived, give various versions of the event (Thapar 2005). In South India, 250 years later, Ala-ud-Din's forces attacked the temple of the Dancing Shiva in Citamparam, and "the kick of the horse of Islam," as the Indo-Persian poet Amir Kusraw put it, destroyed the lingams there (Davis 1997: 133). The seventeenth-century Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, notorious for his chauvinism, particularly hated Varanasi (Benares) because it was the center of lingam-worship, which he regarded as the most abominable of all abominations (Keay 2000: 342). This foreign attitude to the lingam was to have serious repercussions for the attitude of the Hindus themselves.

THE BRITISHBritish historiographers made much of the Muslim destruction of Hindu temples and lingams in order to claim that the British had rescued the Hindus from oppression by Muslims. And many of the British in India, particularly at the start, in the eighteenth century, appreciated all forms of Hindu culture, including its art forms and its eroticism.

But the puritanical Protestant ministers who evangelized India after 1813 were not amused by the copulating couples on the walls of the temples of Khajuraho (built between 900 and 1100 CE in Madhya Pradesh), and they mocked what they regarded as the erotic excesses of the god Krishna. A Supreme Court ruling from 1862 states that "Krishna ... the love hero, the husband of 16,000 princesses ... tinges the whole system [of Hinduism] with the strain of carnal sensualism, of strange, transcendental lewdness" (Bombay [Presidency] Supreme Court 1862: 213).

The British missionaries most despised what they regarded as the obscene idolatry of the lingam. The British in general, who were of course Victorian in every sense of the word, regarded the Hindus, as they regarded most colonized people of color, as simultaneously over-sexed and impotent, and the British presence had a negative effect on the self-perception that Hindus had of their own bodies (Nandy 1983). For, still reeling from the onslaught of the Muslim campaigns against lingams, the Hindus who worked with and for the British internalized their colonizers' scorn. Thus the British taught the Hindus to be ashamed of the more sensual aspects of their own religious literature, particularly of the sexual meanings of the lingam.BURTON AND THE KAMA-SUTRAVictorian British attitudes to Hindu eroticism richocheted between the pornographers and the prudes, and

Sir Richard Burton was certainly not a prude. A connoisseur of eroticism in Arabic as well as Indian culture, he published the first English translation of the Kama-sutra in 1883, a time when the Hindus, cowering under the scorn of the Protestant proselytizers, wanted to sweep it under the Upanishadic rug. The journalist Curt Gentry, in the San Francisco Chronicle, suggested that the publication of Burton's Kama-sutra translation "might act as a useful corrective to the prevailing cliche of India as a land of asceticism" (McConnachie 2007: 194). But Burton and his co-translator, Foster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot (known as "Bunny"), "adroitly managed to escape the smell of obscenity" by using what they presented as "the Hindu terms for the sexual organs, yoni and lingam," throughout their translation (Brodie 1967: 359).

English, unlike Sanskrit, lacks a common register for the sexual organs between the obscene and the medical. To the extent that nineteenth-century writers regarded the words themselves, not the actual things that they designated, as obscene, the foreign words, Sanskrit words, devoid of any English connotations at all, were able to make an end-run around the obscene thought -- not to mention the obscenity laws. The term lingam was perceived as "neither erudite nor earthy, neither gross nor gynaecological" (McConnachie 2007: 129). Arbuthnot elsewhere even attempted to coin the word "yonjic" to match "phallic" (McConnachie 2007: 130).

But this decision of Burton's to use lingam and yoni to represent the sexual organs in the Kama-sutra was problematic in several ways. First, these terms do not represent the text, which only rarely uses lingam to refer to the male sexual organ and never refers to the female sexual organ as a yoni. Where the Kama-sutra does use lingam (KS 2.1.1), the context suggests, and the commentator affirms, that it is gender-neutral, used in its basic lexical sense and meant to apply to both the male and female sexual organs: "The sexual organ is called the "sign" (lingam), because it is the sign of femaleness and so forth." Instead, the Kama-sutra generally uses several other words, primarily a gender-neutral term that can be translated as "pelvis' or "between the legs" (jaghana) or other terms (such as "the instrument" [yantra or sadhana]) that are neither coy nor vulgar. (The exception is the final section of the Kama-sutra, Book Seven, about the use of drugs and sex tools, which has an entirely different tone from the rest of the text and is probably a later addition to it; this section of the text does use lingam for the male sexual organ a few times) (KS 7.1.25, 7.2.8. -15, -25). Yashodhara, the thirteenth-century commentator on the Kama-sutra, sometimes uses lingam and yoni to gloss other terms that the Kama-sutra uses for the sexual organs, but he also uses several other words. So for Burton to use the terms lingam and yoni consistently to translate, as it were, other Sanskrit words for the sexual organs was to create a weird linguistic back-formation.

Second, by Burton's time, the terms lingam and yoni had taken on strong religious overtones, as both Indian English and Indian vernacular languages used these words primarily to designate the stone icons of the god Shiva and his consort. The exclusive application of these two terms to human genitals, therefore, may have had, at the very least, inappropriate overtones and, at the most, blasphemous implications for some Hindus. Yet Burton and Arbuthnot knew the religious meaning of the lingam. Arbuthnot wrote that, "There is in Hindostan an emblem of great sanctity, which is known as the linga-Yoni" (McConnachie 2007: 130).

Finally, the terms lingam and yoni had Orientalist implications for most English readers. The use of any Sanskrit term at all in place of an English equivalent anthropologized sex, distanced it, made it safe for English readers by assuring them, or pretending to assure them, that the text was not about real sexual organs, their sexual organs, but merely about the appendages of weird, dark people far away. This move dodged "the smell of obscenity" through the same logic that allowed National Geographic to depict the bare breasts of black African women long before it became respectable to show white women's breasts in Playboy. (Indeed, in some instances National Geographic actually darkened the skin color of a partially naked Polynesian woman "in order to render her nudity more acceptable to American audiences:) (Lutz and Collins 1993: 82). The use of the term lingam enabled the authors to pretend that the book was not obscene because it was about India, when they really thought it was about sex, and knew that English readers would think so too. And so Sir Richard Burton is the one who really made lingam, in English, into a dirty word. No wonder that the Hindus recoiled from that implication. One begins to see why some Hindus began to be very sensitive about the interpretation of the word lingam.CONTEMPORARY HINDU ATTITUDES TO THE SHIVA-LlNGAMThe history of the word lingam, and the history of the shift in its contexts, demonstrates that we are dealing not just with two bodies of separate texts, one interpreting the lingam sexually and one theologically, but with a tension within each of a number of texts, the same tension between the erotic and the ascetic that characterizes so many other aspects of Hinduism in general and the god Shiva in particular (Doniger O'Flaherty 1973).

Nowadays, many Hindu texts treat the lingam as an aniconic pillar of light or an abstract symbol of god, with no sexual reference. To them, the stone lingams "convey an ascetic purity despite their obvious sexual symbolism" (Hopkins 1971: 9). There is nothing surprising about this. The Sanskrit text that argued that all human beings are born marked with the signs of Shiva and his consort on their bodies -- the lingam and pindi -- implies that humans are born marked with the symbol of their faith, as a Christian might be born with a birthmark in the shape of a cross, or might receive the mark of the stigmata on her palms. "Bunny" Arbuthnot actually wrote a book about what he called The Masculine Cross (McConnachie 1007: 130), that is, the Shiva lingam. But by the late nineteenth century, for many Hindus, a Hindu lingam was no more a penis than a cross was a Roman instrument of execution.

To continue this parallel, some Christians see in the cross a vivid reminder of the agony on Calvary, while others see it as a symbol of their god in the abstract or of Christianity as a religion. But some Hindus, in India but also increasingly in the American diaspora, do not merely see the lingam as an abstract symbol but go on to object to, and attempt to censure, the interpretations of those who view it in more somatic terms. They would be the counterparts of Christians who would refuse to acknowledge that the cross ever referred to the crucifixion of the historical Jesus. These are the ultranationalist exponents of "Hindutva" ("Hinduness"). called "Hindutvadis," who advocate a sanitized, "spiritual" form of Hinduism. There is nothing new in the tension between abstract and earthy interpretations of the lingam in India; what is new is the Hindutva insistence that one of them, the earthy one, is wrong, and must be silenced.

THE GENERAL PROBLEM OF LINGAM SYMBOLISMTo read all the myths of the lingam as the Hindutvadis would insist on doing would be a travesty. If we return to the central episode of the myth about the epiphany of the lingam, and translate the word lingam as such Hindus would have us do, this is what we get:

Shiva stood up from the water. When he saw those creatures of various forms, increasing by themselves, he became angry, and he tore off his own abstract symbol of god and threw it down on the ground, where it stood up just as it was. Brahma said to him. "Why did you tear out your abstract symbol of god and plant it in the ground?" And Shiva replied. "Since someone else created these creatures, what will I do with my abstract symbol of god?" and so forth.

Foolish as this story sounds if we limit ourselves to the most abstract meaning of the lingam, we would be equally wrong to distort the story of Kannappar's lingam with the bleeding eye by translating "the Lord" in that text as "the male organ of Shiva":

One day, Kannappar, the chief of a tribe of hunters, found the male organ of Shiva in the jungle; filled with love for the god and pity that he seemed to be all alone, Kannappar resolved to feed the male organ of Shiva. He kicked aside the flowers that a Brahmin priest had left on the head of the male organ of Shiva and gave him the flowers that he had worn on his own head. His feet, and his dogs' paws, left their marks on the male organ of Shiva ... [and so forth].

This story is about the presence of the god in a very physical, but not at all sexual, form.

To conclude, let us recall that the word lingam primarily means a sign, in the semiotic sense. And we know that signs are always reversible, never reducible. Like myths, symbols change all the time; the greatest of all the survival tactics of a myth, or of a great symbol, is its ability to stand on its head. This flexibility allows a myth or a symbol to be shared by a group (who, as individuals, have various points of view) and to survive through time (through different generations with different points of view) (Doniger 2010: 87-94). This is certainly true of the lingam. Ernst Kantorowicz wrote about the two bodies of medieval European kings, the body politic and the body natural (Kantorowicz 1997). In the same way, we can speak of the sexual lingam and the theological lingam. In order to include the full range of its meanings in our understanding of it, it might be best either to leave the term lingam untranslated, unglossed, like dharma (now an English word), or to settle for the broadest possible meaning, perhaps just "a symbol of the god Shiva."

To paraphrase a line often, wrongly, attributed to Sigmund Freud, sometimes a lingam is just a lingam, but more often, it is both a lingam and a cigar (Doniger 1993). We need to be aware of both the literal and the symbolic levels of the lingam, the historical and the contemporary meanings, simultaneously. Ambivalence toward the lingam was built into the Hindu tradition from that first moment when the Upanishads sketched out a parting of the ways, two divergent paths.

But that ambivalence remained a matter of peaceful coexistence until two foreign states intervened, as the Muslims came and attacked lingams and the British made the Hindus ashamed of them. This set the stage for the final blow, when yet another political movement, the twentieth-century Hindutva faction, condemned and outlawed what they regarded as unacceptable aspects of their own religion, such as the sexual aspects of the Shiva-lingam.

The history of interpretations of the lingam in India reveals the ways that the actions of the state -- in this case, the presence of foreign powers, Muslim and British, who viewed the lingam negatively -- have deeply affected native Hindu perceptions of the body of their own god._______________

NOTES1. An earlier and rather different version of this essay was presented as the 2010 Presidential Lecture at the Art Institute of Chicago, November 11, 2010. I am indebted to James Cuno, Madhuvanti Ghosh, and Mary Sue Glosser for their valuable input on that occasion.

2. In the interest of full disclosure I must confess that I serve on the Britannica's International Board of Editors, and that the Britannica staff consulted me in making this revision.

3. Shiva in this text is called Harikesha (the Tawny-Haired), the Lord of the Mountain, the Eldest, the Lord Rudra, Bhava, and the Guru of the World; I have simplified the text by calling him Shiva throughout, and I have also condensed it somewhat, but added nothing.

4. Verse 2.82 of the Gurucaritra of Sarasvati Gangadhara, c. 1550 CE, composed in Marathi Ovi verse in Ganagapura, a partially Marathi-speaking area of Northern Karnataka, Gulbarga district. I am indebted to Jeremy Morse for this text and translation.

REFERENCESBombay (Presidency) Supreme Court. Report of the Maharaj Libel Case: And of the Bhattia Conspiracy Case. Bombay: Bombay Gazette Press, 1862.

Brahmanda Purana. Bombay: Venkateshvara Steam Press, 1857.

Brihadaranyaka Upanishad (BA). One Hundred and Eight Upanishads, Bombay: Nirnaya Sagara Press, 1913.

Brodie, Fawn M. The Devil Drives: A Life of Sir Richard Burton. New York: Ballantine, 1967.

Cox, Whitney. "The Transfiguration of Tinnan the Archer (Studies in Cekkilar's Periyapuranam I)." Indo-Iranian Journal 48 (2005): 223-252.

Davis, Richard. Lives of Indian Images. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Doniger, Wendy. "When a Lingam Is Just a Good Cigar: Psychoanalysis and Hindu Sexual Fantasies." The Psychoanalytic Study of Society: Essays in Honor of Alan Dundes. Eds. L Bryce Boyer et al. Hillside, N.J.: Analytic Press. 1993. 81-104.

---. The Bedtrick: Tales of Sex and Masquerade. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000.

---. The Implied Spider: Politics and Theology in Myth. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

Doniger O'Flaherty, Wendy. Siva the Erotic Ascetic. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 1973.

---. Hindu! Myths. Harmondsworth: Penguin. 1975.

---. The Rig Veda: An Anthology. 108 Hymns Translated from the Sanskrit. Harmondsworth: Penguin Classics, 1981.

---. Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 1988; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Ferro-Luzzi, Gabriella Eichinger. The Self-Milking Cow and the Bleeding Lingam: Criss-Cross of Motifs in Indian Temple Legends. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1987.

Flood, Gavin. Introduction to the Study of Hinduism. Cambridge. U.K.: Cambridge University Press. 1996.

Hopkins, Thomas J. The Hindu Religious Tradition. Encino. Calif.: Dickenson, 1971.

Kama-sutra (KS) of Vatsyayana, with the commentary of Yashodhara. Ed. with the Hindi "Jaya" commentary by Devadatta Shastri. Varanasi: Kashi Sanskrit Series, 1964.

Kamasutra: A New Translation. Trans. Wendy Doniger and Sudhir Kakar. London and New York: Oxford World Classics, 2002.

Kantorowicz, Ernst H. The King's Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Keay, John. India, a History. New York: Grove Press, 2000.

Kripal, Jeffrey J. Kali's Child: The Mystical and the Erotic in the Life and Teachings of Ramakrishna. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Lutz, Catherine A., and Jane L. Collins. Reading National Geographic. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Mahabharata (M). Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1933- 69.

McConnachie, James. The Book of Love: In Search of the Kamasutra. London: Atlantic, 2007.

McGlashan, Alistair. The History of the Holy Servants of the Lord Siva. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing, 2006.

Marshall, Sir John. Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-daro Carried Out by the Government of India between the Years 1922 and 1927, with Plan and Map in Colours, and 164 Plates in Collotype. 3 vols. London: Arthur Probsthain, 1931.

Nandy, Ashis. The Intimate Enemy: Loss and Recovery of Self under Colonialism. Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1983.

The Narmamala of Kshemendra. Ed. and trans. Fabrizia Baldissera. Wurzburg: Sudasien-Institut, Ergon Verlag, 2005.

Padma Purana (PP). Poona: Anandashrama Sanskrit Series 131, 1893.

Periya Puranam of Cekkilar. Trans. Alistair McGlashan (The History of the Holy Servants of the Lord Siva). Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing, 2006.

Ramanujan, A. K. Speaking of Siva. London: Penguin, 1973.

Rig Veda (RV). With the commentary of Sayana. 6 vols. London: Oxford University Press. 1890-92.

Shulman. David. Siva in the Forest of Pines. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Skanda Purana (SP). Bombay: Shree Venkateshvara Steam Press, 1867.

Thapar. Romila. Somanatha: The Many Voices of a History. London: Verso, 2005.

White, David. Kiss of the Yogini: "Tantric Sex" in its South Asian Contexts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.