Vipassī Buddha

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/18/21

Vipaśyin Buddha

Sanskrit: विपश्यिन् Vipaśyin Buddha

Pāli: Vipassī Buddha

Burmese: ဝိပဿီဘုရား

Chinese: 毗婆尸佛 (Pinyin: Pípóshī Fó)

Japanese: 毘婆尸仏びばしぶつ (romaji: Bibashi Butsu)

Korean: 비파시불 (RR: Bipasi Bul)

Sinhala: විපස්සී බුදුන් වහන්සේ

Thai: พระวิปัสสีพุทธเจ้า Phra Wipatsi Phutthachao

Tibetan: རྣམ་གཟིགས་ Wylie: rnam gzigs

Information

Venerated by: Theravada, Mahayana, Vajrayana

Attributes: Pure Buddha

Preceded by: Puṣya Buddha

Succeeded by: Śikhin Buddha

In Buddhist tradition, Vipassī (Pāli) is the twenty-second of twenty-eight Buddhas described in Chapter 27 of the Buddhavamsa.[1] The Buddhavamsa is a Buddhist text which describes the life of Gautama Buddha and the twenty-seven Buddhas who preceded him. It is the fourteenth book of the Khuddaka Nikāya, which in turn is part of the Sutta Piṭaka. The Sutta Piṭaka is one of three pitakas (main sections) which together constitute the Tripiṭaka, or Pāli Canon of Theravada Buddhism.[2]

The third to the last Buddha of the Alamkarakalpa, Vipassī was preceded by Phussa Buddha and succeeded by Sikhī Buddha.[3]

Etymology

The Pali word Vipassī has the Sanskrit form Vipaśyin. Vi (good) and passī (saw) together mean "having seen clearly". The word belongs to the same family as the term vipassanā (contemplation). This Buddha was so named because he had big eyes, clear vision both day and night, and his insight into perpetual complicated circumstances and very deep theories.

Biography

According to the Buddhavamsa, as well as traditional Buddhist legend and mythology, Vipassī lived 91 kalpas [393 billion years]— many millions of years — before the present time.[4][5] In Vipassī's time, the longevity of humans was 84,000 years.

Vipassī was born in Bandhumatī in Khema Park, in present-day India.[6] His family was of the Kshatriya varna, which constituted the ruling and military elite of the Vedic period. His father was Bandhumā the warrior-chief, and his mother was Bandhumatī. His wife was Sutanu, and he had a son named Samavattakkhandha.[6]

Vipassī lived as a householder for 8,000 years in the palaces of Nanda, Sunanda and Sirimā. Upon renouncing his worldly life, he rode out of the palace in a chariot.[6] Vipassī practiced asceticism for eight months before attaining enlightenment under an Ajapāla nigrodha tree.[5] Just prior to achieving buddhahood, he accepted a bowl of milk rice offered by Sudassana-setthi's daughter, and grass for his seat by a guard named Sujâta.

Sources differ as to how long Vipassī lived. He was reported to have died in Sumitta Park, at the age of either 80,000[6] or 100,000 years.[5] His relics were kept in a stupa which was seven yojanas in height, which is roughly equal to 56 miles (90 km).[6]

Physical characteristics

Vipassī was 80 cubits tall, which is roughly equal to 121 feet (37 m), and his body radiated light for a distance of seven yojanas.[6]

Teachings

Vipassī preached his first sermon in the Khamamigadâya to 6,800,000 disciples, his second sermon to 100,000 disciples, and his third sermon to 80,000 disciples.[5]

His two foremost male disciples were Khanda and Tissa and his two foremost female disciples were Candâ and Candamittâ. Asoka was his personal assistant. His good donors were Punabbasummitta and Naga in the lay men, Sirimâ and Uttarâ in the lay women. Mendaki (then called Avaroja) built the Gandhakuti (scented pavilion) for him. He did the uposatha once every seven years, and the sangha observed the discipline perfectly.

See also

• Buddhist cosmology

• Glossary of Buddhism

• Longevity myths

Notes

1. Morris, R, ed. (1882). "XXVII: List of the Buddhas". The Buddhavamsa. London: Pali Text Society. pp. 66–7.

2. Lancaster, LR (2005). "Buddhist books and texts: canon and canonization". Encyclopedia of religion (2nd ed.). New York: Macmillan Reference USA. p. 1252. ISBN 978 00-286-5733-2.

3. Buddhist Text Translation Society (2007). "The Sixth Patriarchs Dharma Jewel Platform Sutra". The Collected Lectures of Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua. Ukiah, California: Dharma Realm Buddhist Association. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

4. Beal, S (1875). "Chapter III: Exciting to religious sentiment". The romantic legend of Sâkya Buddha: from the Chinese-Sanscrit. London: Trubner & Company, Ludgate Hill. pp. 10–17.

5. Davids, TWR; Davids, R (1878). "The successive bodhisats in the times of the previous Buddhas". Buddhist birth-stories; Jataka tales. The commentarial introduction entitled Nidana-Katha; the story of the lineage. London: George Routledge & Sons. pp. 115–44.

6. Horner, IB (1975). "The nineteenth chronicle: that of the Lord Vipassin". The Minor Anthologies Of The Pali Canon: Part III: Chronicle Of Buddhas (Buddhavamsa) and Basket Of Conduct (Cariyapitaka). Oxford: Pali Text Society. pp. 74–7. ISBN 086013072X.

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Part 1 of 2

Indian Rock Art - Prehistoric Paintings of the Pachmarhi Hills

by Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak

Accessed: 3/18/21

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

This is an account written and translated by Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak, freelance artist and researcher in India, presented here as part of the Bradshaw Foundation India Rock Art Archive. Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak is a member of the Rock Art Society of India (RASI), the Indian Society of Prehistory and Quaternary Studies and the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA), Australia. Dr. Dubey Pathak's extensive research not only brings to light the prehistoric rock art of India but it also highlights the drastic need for its preservation: "This wonderful and precious cultural heritage of ours is facing the danger of extinction by the unaware and uncivilized human beings and their vandalism. The agencies at work must put in a concerted effort to educate the people including the local tribes about the importance of these painted rock shelters and take steps to preserve them before its too late."

INTRODUCTION TO INDIA ROCK ART

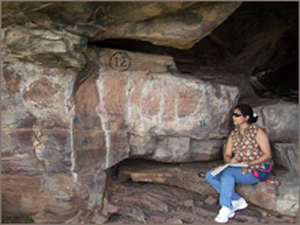

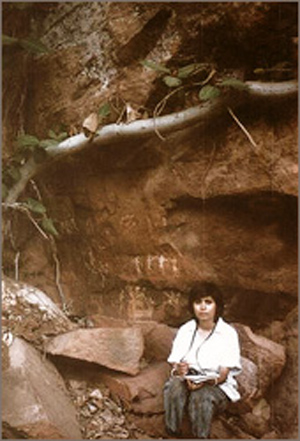

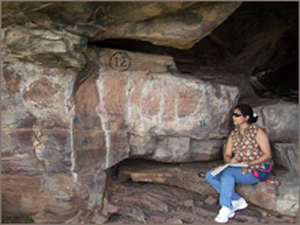

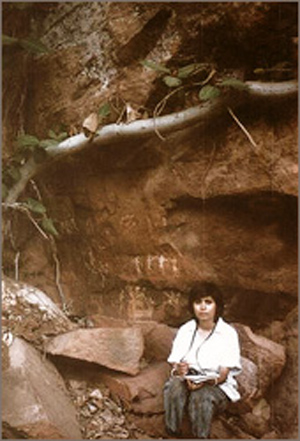

Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak - Gaddie. Rock Art Site in the Vindhachal Ranges

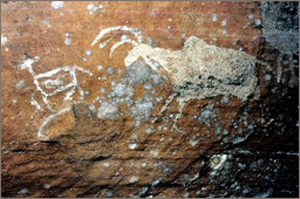

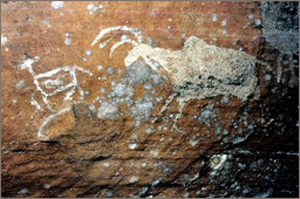

The earliest discovery of prehistoric rock art was made in India, twelve years before the discovery of Alta Mira in Spain. Archibald Carlleyle discovered rock paintings at Sohagihat in the Mirzapur district of Uttar Pradesh in 1867 and 1868. Unfortunately he did not publish. J Cockburn rightly commented that Carlleyle’s knowledge died with him (Smith, 1906: 187). Fortunately, Carlleyle had placed some of his notes with a friend, Reverend Regionald Gatty, and V A Smith published these later, which is the only record of his discovery of Rock paintings. In his note he wrote “Lying along with the small implements in undisturbed soil of the cave floors, pieces of a heavy red mineral-coloured matter called geru were frequently found, rubbed down on one or more facets, as if for making paint. Geru is evidently a partially decomposed hematite (Iron peroxide). “On the uneven sides or walls and roofs of many caves or rock shelters, there are rock paintings apparently of various ages. Though all evidently of great age, done in red colour called geru. Some of these rude paintings appeared to illustrate in a very stiff and archaic manner scenes in the life of the ancient stone chippers. Others represent animals or hunts of animals by men with bows and arrows, spears and hatchets. With regard to the probable age of these stone implements I may mention that I never found a single ground or polished implements not a single ground ring stone or hammer stone in the soil of the floors of any of the many caves or rock shelters I examined.” (Smith 1906: 187).

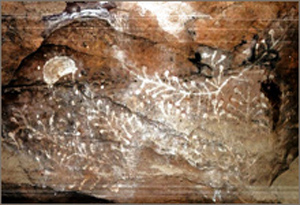

Painted Cave

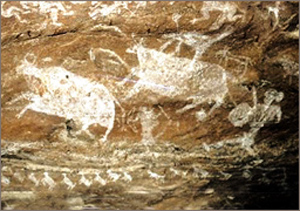

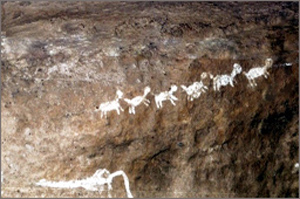

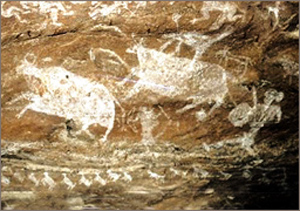

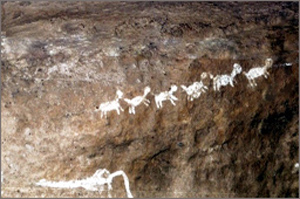

Row of Cows

In 1881 Cockburn had found fossilised rhinoceros bones in the valley of the Ken River in the Mirzapur region as well as a painting of a rhinoceros hunted by three men in a shelter near Roap Village. In 1881 J Cockburn published an account of all his discoveries (J Cockburn 1891: 91). F Fawcett in the cave of Edakal in Kozhikode district of Kerala made the earliest discoveries of rock engravings (Fawcett F 1901: 402-21). A few years later A Silberrad published a pictorial description of the rock paintings in Banda district (Silberred 1970: 567-70). C W Anderson discovered a painted shelter of Singhanpur in the Raigarh district in Madhaya Pradesh (Anderson CW 1981: 298-306). More rock paintings were found later by F R Allchin 1963: 161) (Sundara A 1974: 21-32) and (K Paddayya 1968: 294-98) from the same area as well as the Gulberga district of Karnataka. Manoranjan Ghosh brought the Adamgarh group of painted rock shelters near Hoshangabad in Madhya Pradesh to light in 1932. The first example of rock engravings was discovered in 1933 by K P Jayaswal in a rock shelter at Vikramkhol in the Sambalpur District of Orrisa. (Jayaswal KP 1933: 58-60).

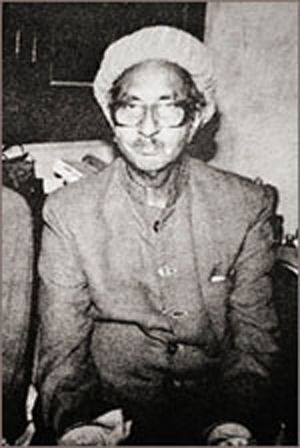

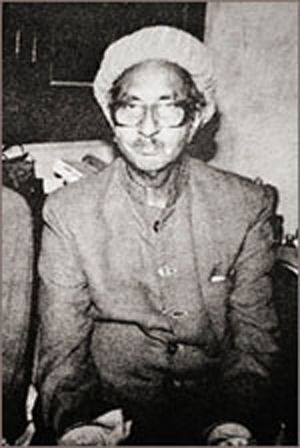

Dr V S Wakankar

As Dr Jean Clottes said, the ‘Father of Indian Rock Art’ and my (Guru) teacher Dr V S Wakankar had discovered several hundred painted shelters mainly in Central India, and attempted a broad survey of the rock paintings of the whole country and prepared a chronology of the paintings based on the content style and superimposition (Wakankar 1973: 251-353). The most important of his discoveries is Bhimbettka near Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh, which has one of the largest concentrations of rock paintings in India. Bright Allchin has published a study of prehistoric art in 1958. R K Verma in 1964, J Gupta 1967, S K Pandey 1961 and J Jacobson 1970 have also contributed to the discovery of Indian rock art. DH Gordon studied the rock paintings of Pachmarhi in the Mahadeo Hills in 1932. He wrote several papers in Indian and foreign journals and has summarised his views on Indian rock art in his book. (Gordon 1958: 98-17).

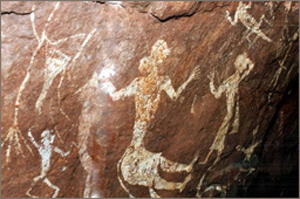

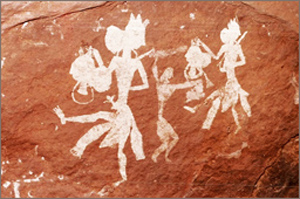

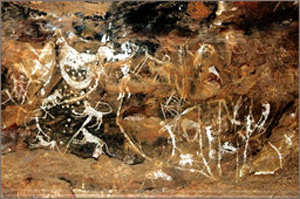

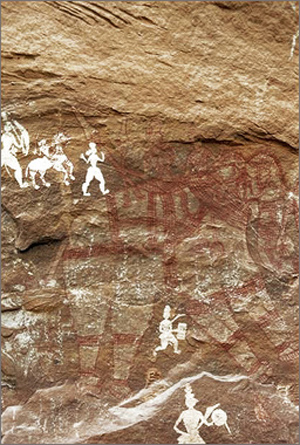

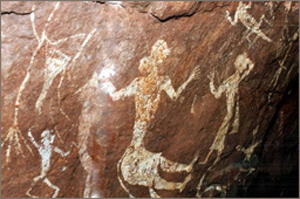

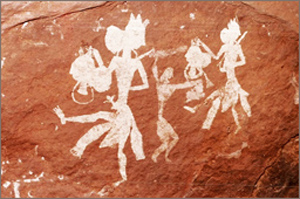

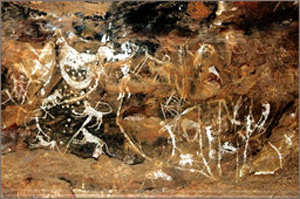

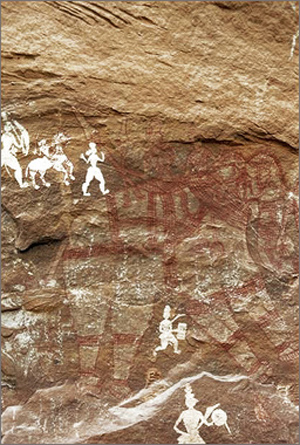

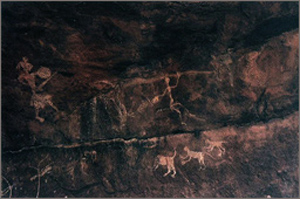

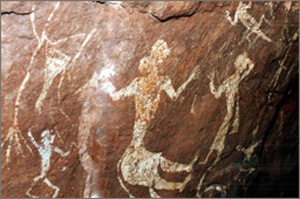

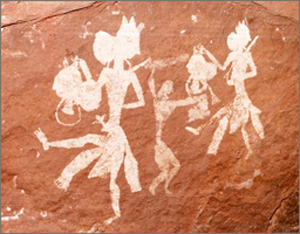

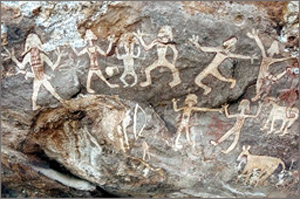

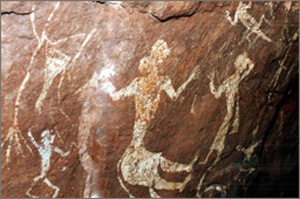

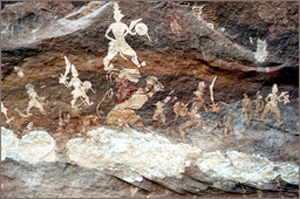

Dancers

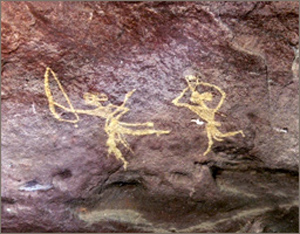

Head Hunters

In recent years Yashodhar Mathpal and Erwin Neumayer have discovered a new group of ten painted shelters on Patni Ki Rahari hill near Bari on Bhopal Bareli road (Mathpal 1976 23: 28). In April 1981 to 1990, with the help of local tribes, I discovered fifteen painted rock shelters in the Pachmarhi Hills. In India over a thousand rock shelters containing paintings are situated in more than 150 sites. In India almost every state has rock art sites of painted shelters and engraved boulders.

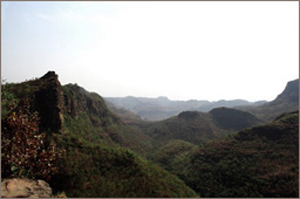

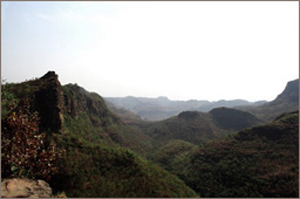

Satpura Ranges India

Dr Meenakshi Pathak

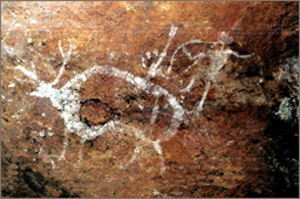

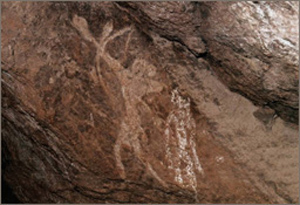

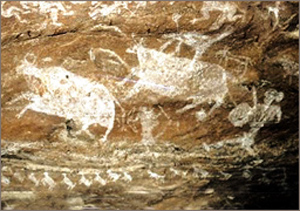

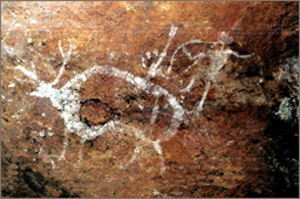

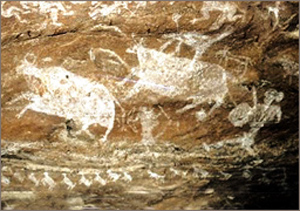

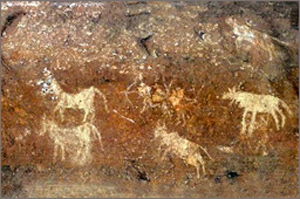

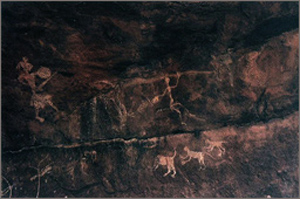

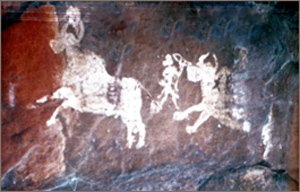

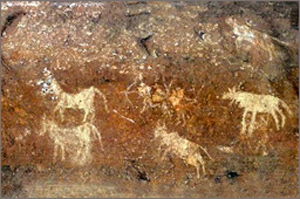

Hunting Scene

Central India is the richest zone of prehistoric rock art in India. The highest concentration of rock art sites is situated in the Satpura, Vindhya and Kaimur Hills. These hills are formed of sandstones, which weather relatively faster to form rock shelters and caves. They are located in the dense forest and were ecologically ideal for occupation by primitives. They were used for habitation in the Stone Age and even in the later periods. Inside the caves on the walls and ceilings artists painted their favourite animals or human forms, symbols, daily life hunting and fighting.

INDIAN ROCK ART: PACHMARHI EXPLORED

The Pachmarhi Hills are situated in the geographical center of the Indian sub continent in the State of Madhya Pradesh. The hills lie in the Satpura Range, formed of the Gondwanaland sandstone belonging to the Gondwanaland series of the Talcher Group formations. The sandstone sequence is of the upper Gondwanaland formation. The sandstone is relatively friable and, on weathering, forms the sandy solid found at the foot of the hills. These hills form one of the most beautiful parts of the Satpura Range. The shelters are found all over the hills and the surrounding forests, in the foothills and riverbanks. Many shelters are covered with paintings made over centuries by early inhabitants depicting a wide range of subjects expressed by them in a variety of styles and left as great heritage for us to understand them and appreciate their unique contribution.

The Pachmarhi Hills

The Pachmarhi Hills

Captain J Forsyth made the discovery of this place, as a sanitarium. Forsyth was sent there in 1862 under the instructions of Sir Richard Temple, Commissioner of that day to explore this portion of the Satpura Forest. Here he built a forest lodge and named it “Bison Lodge”. His famous book “The Highlands of Central India” depicts the exquisite beauties of the Satpura range. The point from where Captain J. Forsyth forest glimpsed the extra ordinary sight of Pachmarhi is still one of the finest points named as “Forsyth point”. When he came to Pachmarhi, the area was occupied by the Korku jagirdar of Pachmarhi, but there were traces of a much older civilization in the shape of sites of ruined huts near “Handi kho” site. The total area of the plateau is about 60 sq kms including the forest area and 12.90 sq kms occupied by the Pachmarhi cantonment.

Part of Forsyth’s report states “Every where the massive group of trees and park like scenery strikes the eye and the greenery of glades and wild flowers, unseen at lower elevation, maintains the illusion that the scene is a bit out of our temperate zone. Thereafter, a multitude of beauty spots were discovered, and the place developed. Much remains the same even today. Pachmarhi still retains its tranquility, its many silences, its gentle green and its soothing forest. It is one place where solitude is miraculously achieved in moments, and the sighs of swaying trees are the only sounds you will hear. Pachmarhi is a lovely hill-girded plateau on the green Satpura range, called by the tourists as the Queen of Satpura." (M.P. Tourists 1962: 4).

By popular belief the name “Pachmarhi” is a derivation of “Pach-marhi” or a complex of five caves of the Pandava brothers, who are supposed to have spent a considerable portion of their lifetime of exile incognito in this area. Genuine place is attainable any where in “Pachmarhi”. Pachmarhi, the legend tells, was once a huge lake guarded by a monstrous serpent. This serpent began terrorizing the pilgrims visiting the sacred shrines of the Mahadeo hills. Lord Shiva, angered by this, hurled his trident at the snake, imprisoning him in the rift of a solid rock, which assumed the shape of a pot or handi. The flames of wrath dried up the lake and empty space assumed the shape of a saucer. Botanists have therefore reported the existence of plants only found by the sides of large expanses of water, these rare penmen of flora seem to bear out the myth! (M P Tourist 74:2).

The hills are thickly vegetated with rich floristic and faunal biota but quite widespread and difficult to access. The natural species represented in the rock art were of great economical importance, having food value for the shelter-dwellers and often form subjects of their painting. Rock paintings found within shelters here are the major sources of our understanding of how their creators related to their physical, biological and cultural environments. These people, as do their descendants at the present time, held beliefs and practices which expressed a direct or indirect relationship between their environment and themselves. Within this body of expression, the evolution of the art form, with the development of mankind over centuries, plays an important and multifaceted role.

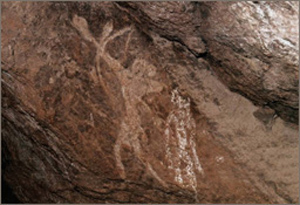

GR Hunter brought the painted rock shelters of Pachmarhi Hills to the notice of D.H. Gordon (1958). Hunter had excavated some sites here in 1932 and again in 1934-35. The 1935 excavation revealed that the cultural sequence within this region commenced during the Mesolithic period, confirming that the Pachmarhi Hills were not occupied during the Palaeolithic. Thus, the rock paintings of this region belong to the Mesolithic and later periods. The Mesolithic paintings clearly depict a society of hunters and gatherers. Mainly they portray man and his relationship with animals. The subject matter of this period is quite varied, although game animals are most frequently represented. Bulls, bison, elephants, wild boars, deer, tigers, buffaloes, dogs, monkeys and crocodiles appear alongside smaller species such as rats, lizards, turtles and fishes. Some of the birds are identified as peacocks, jungle fowl and ostrich. Arthropods, such as scorpions and wild bees, were also depicted. The hunters are portrayed using spears, axes, sticks and bows and arrows.

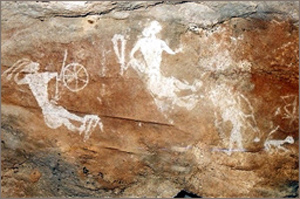

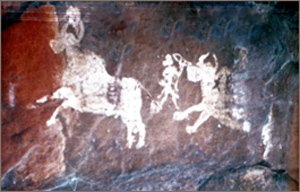

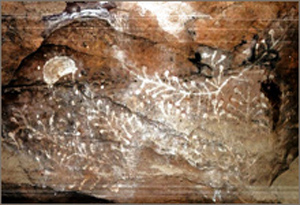

Hunting Wild Buffalo

Stag Hunting

Female figures are occasionally shown. Sexual life does have a place in Mesolithic art but is not very prominent, and male and female union is rarely shown. It seems that dances were important for ceremonial or entertainment purposes during this period. For these dances headdresses and animal masks representing donkeys, crocodiles, bulls or monkeys were worn. The compositional elements of these Mesolithic paintings are highly developed. They represent an element of the creative spirit of the early people. That their aesthetic sense had developed to a high degree can be seen in geometric designs and in paintings of the X-ray style. Pregnant animals such as cow and deer depict the fetus in the womb. Most interesting depiction is a urinating cow. It suggests the awareness of medicinal value of cow urine to the primitives. As we all know according to Indian Ayurved cow urine is a very good treatment for cancer patients and for other ailments. Head Hunters are another interesting depiction . A variety of animals can be seen from elephants to ants.

Pregnant Animal with fetus in the Womb

Urinating Cow

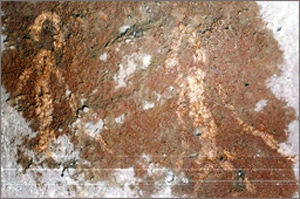

X-Ray Style Rock Art Painting

X-Ray Style Rock Art Painting

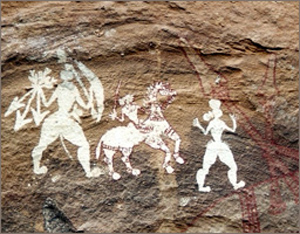

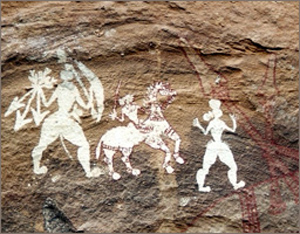

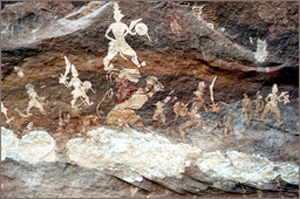

In the Pachmarhi Hills most of the paintings are from the Chalcolithic to the Historical period. Conflict is one of the main themes depicted during this time. War scenes are common but reasons for conflict are not indicated. Horsemen armed with swords and shields overlie the earlier paintings portraying the life of hunters and gatherers. They bear elaborate war equipment consisting of spears, axes, swords, shields, daggers and bows and arrows. Other individuals carry drums and trumpets, and foot soldiers as well as men riding caparisoned horses and elephants are depicted. Goats, dogs, oxen, donkeys and performing monkeys accompany the troops. The descendants of the original hunters and gatherers and artists of this region are the tribal Korku and Gond who still uphold some of the traditions of their ancestors. In the rock paintings their ancestors are depicted dancing in pairs or in rows and playing musical instruments. They hunted animals and collected honey from the hives of wild bees. Their mode of dress was quite simple. The women carried food and water and looked after the children. The forebearers of the present day tribal people had a variety of ways to express the magic of their beliefs, rituals and taboos. The tribes living in these hills have wooden memorial boards on which the carved horse and its rider is similar to those painted by their predecessors in the past on the walls of their rock shelters . They also decorate the walls of their houses and this activity seems to have its roots in the cave dwelling traditions of their ancestors. Men and horses of geometric construction are randomly spaced across the walls. Such paintings are done during the rainy season and on festive occasions, and bear a close resemblance to those found in the painted shelters.

Soldiers

Bees Nest

Presently, the wall paintings in their houses, as in the great majority of rock paintings, are executed in red and yellow pigments prepared from hematite or other iron oxides. The white pigment was made from limestone or kaolin, while mixtures of pigment that produce pinks are also found used in paintings. The rock paintings were executed in a number of stylistic conventions. Some are only sketches or constructs of lines, while others are silhouettes filled with colours and embellished with decorative designs.

ANTIQUITY OF PACHMARHI INDIA

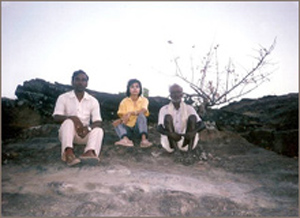

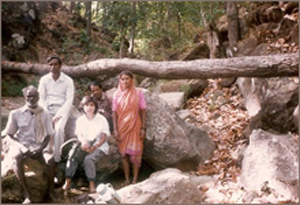

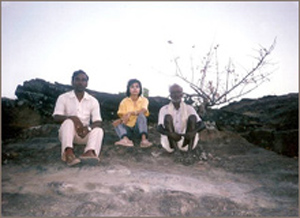

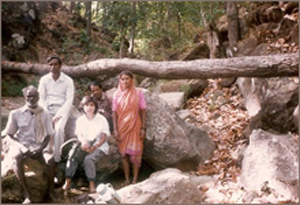

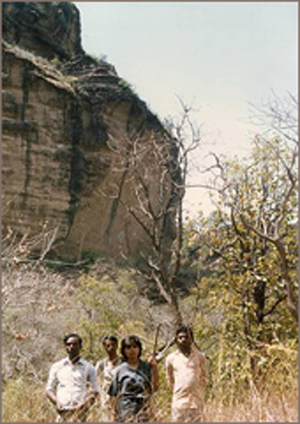

Dr Meenakshi Pathak with her team in the Pachmarhi Hills

Considerable information is now available about the antiquity of Pachmarhi from Archaeological sources. The excavation by archaeologists in different shelters has provided sufficient archaeological data of the people who occupied these shelters. Excavations were conducted in rock shelters since 1932 by GR Hunter. He introduced the cave art of Pachmarhi in his lecture before the congress of the pre-proto historic science in 1932, which brought the painted rock shelters of Pachmarhi Hills to the notice of Lt Col DH Gordon. Hunter excavated here in 1932 and 1934-35 (Hunter-1955).

Cupules on Sand Stone

Clear evidence of Mesolithic culture has come from the Dorothy Deep shelter. The 1932 excavation was confined to the Nallah area, and a trial pit close to the rock wall up to 2’ and the 1934 excavation by a trial trench right across the breadth of the cave up to 5’ depth with undisturbed stratification. The earliest deposit was of the Mesolithic (Tardenoisian) period. The multiplicity of shapes and sizes, characteristic of most stone age cultures, suggests occupation prior to the Neolithic and the metal ages. Subsequently, the shelter was occupied by a culture using pottery. The excavator thought that though there was no sterile deposit between the two cultures, and quartz flakes were found in the upper layers where pottery abounds. It was doubtful if there was any overlap.

Three skeletons were found in association with the typical Tardenoisian flakes and implements but without any beads or other objects. Only two small pieces of cranium were found to be intact. Thus the following sequence has been worked out:

The excavation of 1935 followed the above sequence and attempted to establish the inference that the Palaeolithic man never inhabited the Mahadeo Hills. Divisible into three sub phases - upper, middle and lower. There was a definite cultural development during the Mesolithic age, in the technique of flaking, leading to the evolution of patterns more suited to the purpose. These tools are similar to those recovered from the Tardenoisian and Caspian sites in Europe and Africa (M.D. Khare 1984; 130). In 1950 A. Ghosh excavated Baniya Berry shelter where a trench of 22”X39” was dug and four layers were found. The lowest consisted of weathered sandstones and yielded no finds. Layer 3 - yellow brown soil mixed with stone chips, geometric microliths, pre pottery period. Layer 2 - of similar soil, also yielded geometric microliths. Layer 1 - top layer dark brown earth, no tools. This suggests the shelter was inhabited only during the Mesolithic period.

Then S K Pandey excavated two rock shelters in 1968. The first shelter was Jambu Dweep in which digging was barely 6 inches deep. It yielded small numbers both of microliths and pottery shreds. Another shelter, Baniya Berry, the excavation was in two distinct layers. The lower layer had loose sandy soil, with one large chalcedony piece, 2 Jasper flakes, 2 triangles and 28 chips. The upper layer of brown earth produced fluted cores and 4 parallel one-sided flakes. There was no pottery in this shelter.

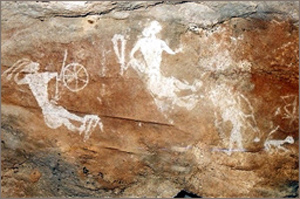

Complex Hunting/Battle Scene

Panel with Figures & Monkeys

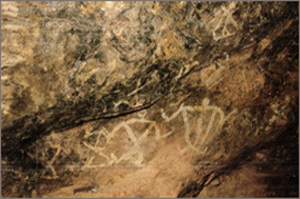

Depiction of Horses

Triangular Figures

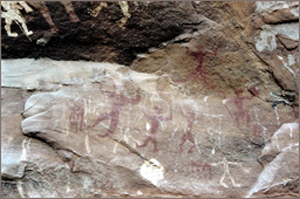

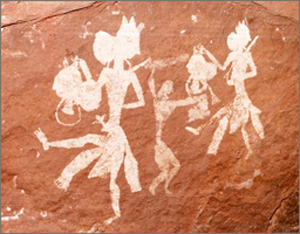

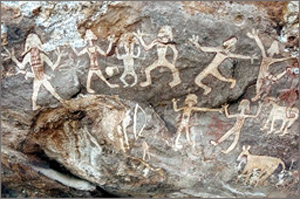

Dancing Figures

Dancing Figures

During my field research work in the year 1990-91, I collected some Mesolithic pottery shreds, a few tiny pieces of bone and a pendent of the tooth of an herbivorous animal (monkey) from the loose surface of the shelters. Total finding of microliths: Trapeze - 1, blades - 34, side scraper - 8, and burins - 2.

Mesolithic technology, introduced from outside, supplemented the older technology with the passage of time. It consists of Mesolithic tools made of slender micro blade, which were first detached from cylindrical cores by a pressure technique and then blunted on one or more margins. These tools, made of fine-grained rocks, lime, chert and chalcedony, comprise blunted back blades, obliquely truncated bladed, points, crescents triangles and trapezes. By hafting them into bone or wooden handles, these tiny tools were utilized to make knives, arrowheads, spear heads and sickles. Colour nodules are also found in the loose surface. Yellow colour nodules have been found in Bori shelter.

The gradual developments of changes can be seen in this area regarding the use of fire and construction of floors of stone slabs. In the later phases the appearance of copper tools and pottery suggests contact between the Mesolithic people of shelters and Chalcolithic people of the plains. In the upper most layers, early historic pottery shows the persistence of Mesolithic way of life up to the historic times.

ABORIGINALS

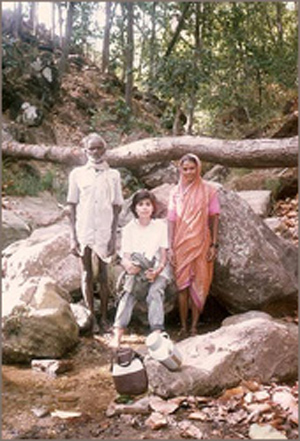

Dr Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak and the Research Team

The population of Pachmarhi is principally tribal. The main tribes are Korku and Gond. The four-sub caste of Korku is Muwasi, Bawaria, Ruma and Bondoya. The word Korku means simple men or ‘tribesmen’. (Koru meaning 'man' and ku its plural). According to Korku, traditions of their origin, on the request of Ravana, Lord Mahadeo created two images of a man and woman from the clay of an anthill. He then infused life into these figures and they were called ‘Mula’ and ‘Mulai’, with a common surnames Pathre. These two were the ancestors of the Korku tribe. Korku are a Munda or Colarian tribe as their language belongs to the Mundari of Austro-Asiatic family. The Gond tribes speak Gondi language. The Gonds also call themselves ‘Ravanvasi’, meaning descendants of Ravana king of Lanka. Their legends suggest that they have migrated to the area from Andhra in the medieval period, and they speak a Dravidian language called Gondi. The Korkus consider themselves superior to Gonds. They would not take food from Gonds, but would not refused water and chilam (cigar).

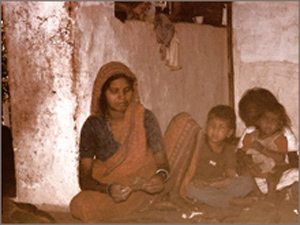

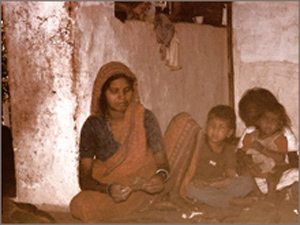

Tribal Village

The average Korkus are well built & muscular. They have a round face, a nose rather wide, prominent cheekbone, a scanty mustache and his head shaved after the Hindu fashion. They are slightly taller than Gond (Russel and Hiralal 1969 : 552). They make houses of wattle and daub and with roofs made of handmade, baked clay tiles. The locals generally sleep on the ground and a few low stools carved from teak wood serve them as pillows. There is generally a verandah in the front of the house, a cattle shed attached to the side. The villages are kept remarkably clean.The interior of the house in Korku village is kept clean. The walls are decorated with various designs drawn on festive occasion, and the villagers take delight in pasting coloured pictures on the interior walls of their hut for decoration. Every villager has a few pigs and fowls about and both of which are eaten after being sacrificed. They are by no means particular about what they eat, fowls, fish, crabs and tortoise all consumed. Bondoya korku eat buffaloes too. The millets (kodu - kutki) are grown principally in the hilly tracks of trivial inhabitant, which form the staple food. Tobacco smoking and country liquor made by the local mahua flower is very common among these aboriginals. They often supplement their food with a number of edible fruits, tubers and honey collected from the forest. The tribal economy depends on agriculture.

Like most hill tribes the korku are remarkably honest and truthful. Korku consider themselves to be Hindus, and are held to have a better claim to a place in the social structure of Hinduism than most of the other forest tribes. They worship the Sun, Moon and also Mahadeo. The main festivals among Korku tribe are Shivaratri and Nagapanchami. Pachmarhi is the important pilgrim center for Shivaratri and Nagapanchami fares. The priests of Korku are of two kinds: ‘Parihars’ and Bhumka’. The Pariahs may be any man who is visited with the divine afflatus or selected as a mouthpiece by the deity. Parihars are also rare, but every village has it Bhumka, who perform the regular sacrifices to the village gods and the special ones entailed by disease or other calamities. The Korku have some belief in sympathetic magic as other primitive people. They also trust in Omens.

Korku tribe also has funeral rites. The dead are usually buried, the head pointing to the south. The earth is mixed with thorns while being filled in so as to keep off hyenas and stones are placed over the grave. Their family members and relatives honor the dead with carved and decorated teak wood memorial boards, placed under a sacred tree in the memory of the deceased during a highly religious ceremony. The primitive men in Hoshangabad district used painting as the chief source of amusement. Pachmarhi and Adamgarh hillock is the living monument of their art. The times have changed and there is a variety of means of amusement available to the people now.

CONTEMPORARY TRIBAL ART OF PACHMARHI INDIA

In the remote mountains, deep dense forests, swamps and deserts the lives of hunters and gatherer remained almost undisturbed, long after more advanced cultures settled in the valleys and lowlands. The tribal people living in the rock shelters observed the colonizing groups and recorded their activities in paintings on the walls of their rock shelters. Later, they were to adopt from the newcomers only few basic cultural items. This is the most complete record, supported by the evidence of archaeological remains, of the tribal culture, as it existed in the past.

Huge Shelter Occupied by the Local Tribes

Dr Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak with Local Tribe near Shelter

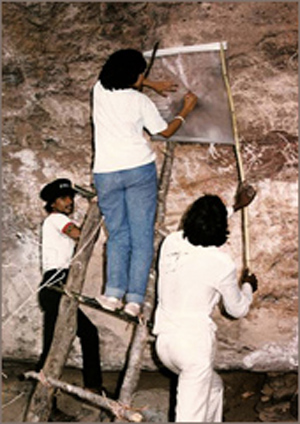

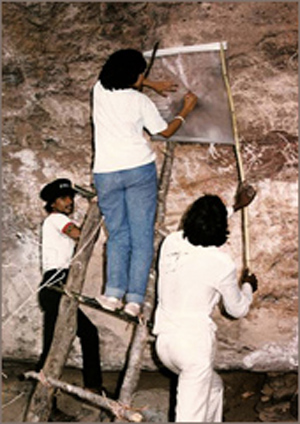

Tracing the Rock Art at the Nagdwari Cave

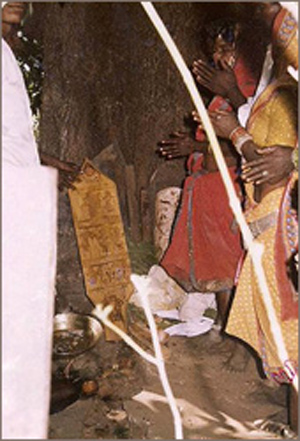

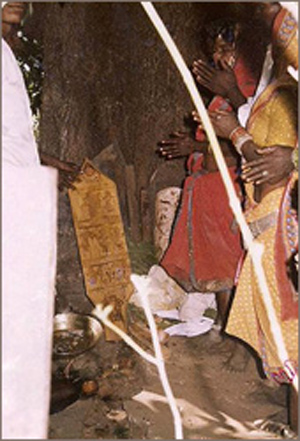

Over time the valley culture exerted greater influence on the tribal groups. They left the rock shelters and the painted record ceased. Although this occurred only a few hundred years ago, there exist only a few, more recent paintings, which may be linked to the earlier examples of rock art. The Korku honour their deceased members with carved and decorated teak wood memorial boards, which are placed under a sacred tree in their memories during the highly religious ceremony. This may last for seven to eight hours. During the ceremony the tribe females dance in a circle around the sacred mango tree. In between they hold the memorial board in their hands and dance.

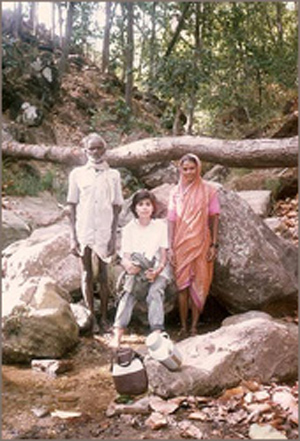

Dr Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak with Tribal Couple

Memorial Board placed under a Sacred Tree

Memorial Board placed under a Sacred Tree

Following this the carved boards are venerated and wept over. Later, a goat or jungle fowl is sacrificed and eaten, while the local liquor made from the flowers of the Mahua tree (Bassia latifolia) is consumed. One such sacred tree is situated in the “Gond Baba Udhayan” (lit. - Garden of the Gond deity) located in the Pachmarhi town itself. Tribal people who come from the surrounding villages of Pachmarhi use this site for their religious rituals followed by feasts. Memorial boards are placed at the base of the sacred tree within ten years of a death. The subjects carved into the board are selected form a limited list of elements. These are usually horse riders; group of geometrical human figures holding hands, and representations of sun or moon and the name of the deceased.

In carvings of the horse and its rider the Korku do not depict their own ancestors, as they did not have horses. The figures mounted on horse represent their conquerors. This element of the carving is totally unrelated to the loves of the deceased, but its stylistic form and that of other human figures is similar to the more recent rock paintings situated in rock shelters only a few kilometers away (Wakankar and Brooks 1976: 16).

Women of the Tribe busy with their daily routine

Many of the present day tribal communities decorate the walls of their house with paintings. The selected subjects relate to their natural and cultural environments, depicting birds, floral patterns, whilst other appears to be of symbolic or ritual importance. These wall paintings also seem to have their roots in the rock art tradition. At present the Korku tribal live in wattle huts whose walls are coated by clay colored white. The tradition of paintings continues as the korku women decorated their house walls with paintings and sketches. They use local colour such as the dark or Indian red, yellow ochre, blue and white. The paintings are executed during the slack rainy season or occasionally during festival events. The women in the Korku society carry out all domestic work and look after the children.

The depiction of a peacock on the wall of a hut in the Kajri village situated 35 kilometers from Pachmarhi town is very similar to rock paintings found recently in the Langi Hill shelter . A symbol painted on the same repaired wall closely resembles a rock painting of the Swem Aam shelter that has only been recently explored. That the two traditions share the same roots can be seen in the common subject matter and the continuing stylistic conventions displayed by the contemporary art.

INDIAN ROCK ART : PACHMARHI THEMES

The subject matter in rock art can be very varied. The main subject everywhere is the animal or scenes of hunting them, which is the most common subject of rock paintings belonging to the Mesolithic and later periods. The subject matter of rock paintings also helps in studying many facets of human life. "The depictions of the species of animals, human and the food gatherers tell us much about the ecosystem in which they lived. The depiction of weapons, tools and other implements reveal their technical abilities. The illustration of his myths and beliefs bring back to our consciousness the essential aspects of out intellectual roots and displays the existential relationship between man, nature and the supernatural" (Anati-1980-20).

In the Indian rock paintings the presentation of man and animals is of almost the same standard although stylistically there are many differences (Mathpal 1980- 93). The artist did not represent everything he saw or knew. Besides animals and their hunters, there are other subjects depicted in rock art via social and cultural activities, ritual performances, domestic life and different images of women, such as mother with a child. In the early period human figures are rarely painted and the depiction is only symbolic and stick-shaped. Many human figures are conical animalized (Gordon 1960- 512), grotesque (Breuil and Lantier 1965- 187) and disproportionate (Bernguer 1973:40?45). In the rock paintings of Pachmarhi Hills prehistoric artists had depicted many cultural dimensions of their life and surroundings. Artists of early and later periods were greatly interested in the depiction of ritual dance and music. In the later period different types of musical instruments, battle scenes, soldiers, horse riders, symbols, patterns etc depicted them. The subject matter of the rock painting of Pachmarhi has been divided into the following categories: -

(a) Human forms. (b) Animal forms. (c) Scenes. (d) Material culture. (e) Mythology. (f) Nature. (g) Inscriptions.

HUMAN FORMS

Human beings are painted lesser realistically than the animals. There are total 2449 human forms belonging to all the periods in Pachmarhi. These forms have been divided into the following 30 sub-groups according to the subject matter: -

(a) Man. (b) Women. (c) Boy. (d) Girl. (e) Infant. (f) Hunter. (g) Fighter. (h) Rider. (i) Attendant. (j) Dancer. (k) Drummer. (l) Pipe Player. (m) Harp Player. (n) Cymbal Player. (o) Man with Mask. (p) Man with Kanvar. (q) Man with animal hide. (r) Women with sickle. (s) Man with axe or (Tree cutter). (t) Honey Collector. (u) Ritual performer. (v) Head Hunter. (w) Leader. (x) Mother Goddess. (y) Copulation. (z) Man in Hut. (aa) Anthropomorphic. (ab) Women engaged in domestic chores. (ac) Pregnant Women. (ae) Fragmented Figures.

Figures with Tiger

Archer

ANIMAL FORMS

Elephant

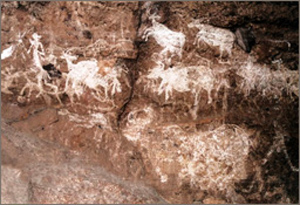

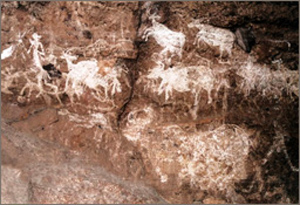

Normally animal forms part of a hunting scene. A good number of the large or medium size animal’s figures have been painted naturalistically. The common most details are their horns, snout and ears. The animal drawings of early period are very natural and more realistic than those belonging to the later period. In the earliest period the animals were depicted in considerable size, beautifully decorated with abstract and geometric patterns. There are nearly 1008 images of animals belonging to 25 different species. These species comprise Tiger, Leopard, Elephant, Wild buffalos, Bison, Oxen, Cow, Nilgai, Sambhar, Swamp deer, Wild boar, hyena, wolf Dog, Monkey, Horse, Pangolin, crocodile and probably a giraffe like long necked animal. Drawing of Porcupine, Rabbit and small creatures like Lizard, Scorpion and Fish are also found. Drawings of birds such as jungle fowl, peafowl and some ostrich like unidentified birds are also recorded. Some depiction of insects like centipedes and honeybees has also been found.

Goats

Monkeys

Bison with Lizard

Row of Cows

Ascetically Drawn Bison Panel

Hunters with Birds

• BIRDS

Total 37 drawings of a limited variety of birds have been found in various shelters in Pachmarhi Probably birds did not form major part of food but only an object of entertainment and curiosity in their surroundings and thus did not receive much significance in the lives of pre-historic men.

• MISCELLANEOUS

Different types of fish, turtles, scorpions, lizards, insects like centipede and honey bees have been depicted in different shelters.

Indian Rock Art - Prehistoric Paintings of the Pachmarhi Hills

by Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak

Accessed: 3/18/21

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

This is an account written and translated by Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak, freelance artist and researcher in India, presented here as part of the Bradshaw Foundation India Rock Art Archive. Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak is a member of the Rock Art Society of India (RASI), the Indian Society of Prehistory and Quaternary Studies and the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA), Australia. Dr. Dubey Pathak's extensive research not only brings to light the prehistoric rock art of India but it also highlights the drastic need for its preservation: "This wonderful and precious cultural heritage of ours is facing the danger of extinction by the unaware and uncivilized human beings and their vandalism. The agencies at work must put in a concerted effort to educate the people including the local tribes about the importance of these painted rock shelters and take steps to preserve them before its too late."

INTRODUCTION TO INDIA ROCK ART

Dr. Meenakshi Dubey Pathak - Gaddie. Rock Art Site in the Vindhachal Ranges

The earliest discovery of prehistoric rock art was made in India, twelve years before the discovery of Alta Mira in Spain. Archibald Carlleyle discovered rock paintings at Sohagihat in the Mirzapur district of Uttar Pradesh in 1867 and 1868. Unfortunately he did not publish. J Cockburn rightly commented that Carlleyle’s knowledge died with him (Smith, 1906: 187). Fortunately, Carlleyle had placed some of his notes with a friend, Reverend Regionald Gatty, and V A Smith published these later, which is the only record of his discovery of Rock paintings. In his note he wrote “Lying along with the small implements in undisturbed soil of the cave floors, pieces of a heavy red mineral-coloured matter called geru were frequently found, rubbed down on one or more facets, as if for making paint. Geru is evidently a partially decomposed hematite (Iron peroxide). “On the uneven sides or walls and roofs of many caves or rock shelters, there are rock paintings apparently of various ages. Though all evidently of great age, done in red colour called geru. Some of these rude paintings appeared to illustrate in a very stiff and archaic manner scenes in the life of the ancient stone chippers. Others represent animals or hunts of animals by men with bows and arrows, spears and hatchets. With regard to the probable age of these stone implements I may mention that I never found a single ground or polished implements not a single ground ring stone or hammer stone in the soil of the floors of any of the many caves or rock shelters I examined.” (Smith 1906: 187).

Painted Cave

Row of Cows

In 1881 Cockburn had found fossilised rhinoceros bones in the valley of the Ken River in the Mirzapur region as well as a painting of a rhinoceros hunted by three men in a shelter near Roap Village. In 1881 J Cockburn published an account of all his discoveries (J Cockburn 1891: 91). F Fawcett in the cave of Edakal in Kozhikode district of Kerala made the earliest discoveries of rock engravings (Fawcett F 1901: 402-21). A few years later A Silberrad published a pictorial description of the rock paintings in Banda district (Silberred 1970: 567-70). C W Anderson discovered a painted shelter of Singhanpur in the Raigarh district in Madhaya Pradesh (Anderson CW 1981: 298-306). More rock paintings were found later by F R Allchin 1963: 161) (Sundara A 1974: 21-32) and (K Paddayya 1968: 294-98) from the same area as well as the Gulberga district of Karnataka. Manoranjan Ghosh brought the Adamgarh group of painted rock shelters near Hoshangabad in Madhya Pradesh to light in 1932. The first example of rock engravings was discovered in 1933 by K P Jayaswal in a rock shelter at Vikramkhol in the Sambalpur District of Orrisa. (Jayaswal KP 1933: 58-60).

Dr V S Wakankar

As Dr Jean Clottes said, the ‘Father of Indian Rock Art’ and my (Guru) teacher Dr V S Wakankar had discovered several hundred painted shelters mainly in Central India, and attempted a broad survey of the rock paintings of the whole country and prepared a chronology of the paintings based on the content style and superimposition (Wakankar 1973: 251-353). The most important of his discoveries is Bhimbettka near Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh, which has one of the largest concentrations of rock paintings in India. Bright Allchin has published a study of prehistoric art in 1958. R K Verma in 1964, J Gupta 1967, S K Pandey 1961 and J Jacobson 1970 have also contributed to the discovery of Indian rock art. DH Gordon studied the rock paintings of Pachmarhi in the Mahadeo Hills in 1932. He wrote several papers in Indian and foreign journals and has summarised his views on Indian rock art in his book. (Gordon 1958: 98-17).

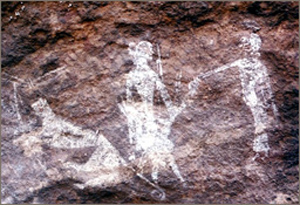

Dancers

Head Hunters

In recent years Yashodhar Mathpal and Erwin Neumayer have discovered a new group of ten painted shelters on Patni Ki Rahari hill near Bari on Bhopal Bareli road (Mathpal 1976 23: 28). In April 1981 to 1990, with the help of local tribes, I discovered fifteen painted rock shelters in the Pachmarhi Hills. In India over a thousand rock shelters containing paintings are situated in more than 150 sites. In India almost every state has rock art sites of painted shelters and engraved boulders.

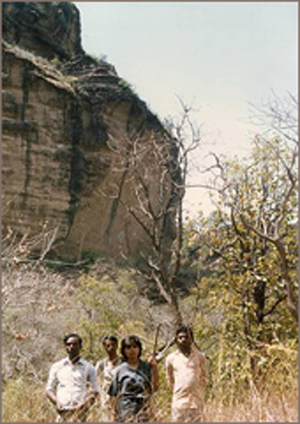

Satpura Ranges India

Dr Meenakshi Pathak

Hunting Scene

Central India is the richest zone of prehistoric rock art in India. The highest concentration of rock art sites is situated in the Satpura, Vindhya and Kaimur Hills. These hills are formed of sandstones, which weather relatively faster to form rock shelters and caves. They are located in the dense forest and were ecologically ideal for occupation by primitives. They were used for habitation in the Stone Age and even in the later periods. Inside the caves on the walls and ceilings artists painted their favourite animals or human forms, symbols, daily life hunting and fighting.

INDIAN ROCK ART: PACHMARHI EXPLORED

The Pachmarhi Hills are situated in the geographical center of the Indian sub continent in the State of Madhya Pradesh. The hills lie in the Satpura Range, formed of the Gondwanaland sandstone belonging to the Gondwanaland series of the Talcher Group formations. The sandstone sequence is of the upper Gondwanaland formation. The sandstone is relatively friable and, on weathering, forms the sandy solid found at the foot of the hills. These hills form one of the most beautiful parts of the Satpura Range. The shelters are found all over the hills and the surrounding forests, in the foothills and riverbanks. Many shelters are covered with paintings made over centuries by early inhabitants depicting a wide range of subjects expressed by them in a variety of styles and left as great heritage for us to understand them and appreciate their unique contribution.

The Pachmarhi Hills

The Pachmarhi Hills

Captain J Forsyth made the discovery of this place, as a sanitarium. Forsyth was sent there in 1862 under the instructions of Sir Richard Temple, Commissioner of that day to explore this portion of the Satpura Forest. Here he built a forest lodge and named it “Bison Lodge”. His famous book “The Highlands of Central India” depicts the exquisite beauties of the Satpura range. The point from where Captain J. Forsyth forest glimpsed the extra ordinary sight of Pachmarhi is still one of the finest points named as “Forsyth point”. When he came to Pachmarhi, the area was occupied by the Korku jagirdar of Pachmarhi, but there were traces of a much older civilization in the shape of sites of ruined huts near “Handi kho” site. The total area of the plateau is about 60 sq kms including the forest area and 12.90 sq kms occupied by the Pachmarhi cantonment.

Part of Forsyth’s report states “Every where the massive group of trees and park like scenery strikes the eye and the greenery of glades and wild flowers, unseen at lower elevation, maintains the illusion that the scene is a bit out of our temperate zone. Thereafter, a multitude of beauty spots were discovered, and the place developed. Much remains the same even today. Pachmarhi still retains its tranquility, its many silences, its gentle green and its soothing forest. It is one place where solitude is miraculously achieved in moments, and the sighs of swaying trees are the only sounds you will hear. Pachmarhi is a lovely hill-girded plateau on the green Satpura range, called by the tourists as the Queen of Satpura." (M.P. Tourists 1962: 4).

By popular belief the name “Pachmarhi” is a derivation of “Pach-marhi” or a complex of five caves of the Pandava brothers, who are supposed to have spent a considerable portion of their lifetime of exile incognito in this area. Genuine place is attainable any where in “Pachmarhi”. Pachmarhi, the legend tells, was once a huge lake guarded by a monstrous serpent. This serpent began terrorizing the pilgrims visiting the sacred shrines of the Mahadeo hills. Lord Shiva, angered by this, hurled his trident at the snake, imprisoning him in the rift of a solid rock, which assumed the shape of a pot or handi. The flames of wrath dried up the lake and empty space assumed the shape of a saucer. Botanists have therefore reported the existence of plants only found by the sides of large expanses of water, these rare penmen of flora seem to bear out the myth! (M P Tourist 74:2).

The hills are thickly vegetated with rich floristic and faunal biota but quite widespread and difficult to access. The natural species represented in the rock art were of great economical importance, having food value for the shelter-dwellers and often form subjects of their painting. Rock paintings found within shelters here are the major sources of our understanding of how their creators related to their physical, biological and cultural environments. These people, as do their descendants at the present time, held beliefs and practices which expressed a direct or indirect relationship between their environment and themselves. Within this body of expression, the evolution of the art form, with the development of mankind over centuries, plays an important and multifaceted role.

GR Hunter brought the painted rock shelters of Pachmarhi Hills to the notice of D.H. Gordon (1958). Hunter had excavated some sites here in 1932 and again in 1934-35. The 1935 excavation revealed that the cultural sequence within this region commenced during the Mesolithic period, confirming that the Pachmarhi Hills were not occupied during the Palaeolithic. Thus, the rock paintings of this region belong to the Mesolithic and later periods. The Mesolithic paintings clearly depict a society of hunters and gatherers. Mainly they portray man and his relationship with animals. The subject matter of this period is quite varied, although game animals are most frequently represented. Bulls, bison, elephants, wild boars, deer, tigers, buffaloes, dogs, monkeys and crocodiles appear alongside smaller species such as rats, lizards, turtles and fishes. Some of the birds are identified as peacocks, jungle fowl and ostrich. Arthropods, such as scorpions and wild bees, were also depicted. The hunters are portrayed using spears, axes, sticks and bows and arrows.

Hunting Wild Buffalo

Stag Hunting

Female figures are occasionally shown. Sexual life does have a place in Mesolithic art but is not very prominent, and male and female union is rarely shown. It seems that dances were important for ceremonial or entertainment purposes during this period. For these dances headdresses and animal masks representing donkeys, crocodiles, bulls or monkeys were worn. The compositional elements of these Mesolithic paintings are highly developed. They represent an element of the creative spirit of the early people. That their aesthetic sense had developed to a high degree can be seen in geometric designs and in paintings of the X-ray style. Pregnant animals such as cow and deer depict the fetus in the womb. Most interesting depiction is a urinating cow. It suggests the awareness of medicinal value of cow urine to the primitives. As we all know according to Indian Ayurved cow urine is a very good treatment for cancer patients and for other ailments. Head Hunters are another interesting depiction . A variety of animals can be seen from elephants to ants.

Pregnant Animal with fetus in the Womb

Urinating Cow

X-Ray Style Rock Art Painting

X-Ray Style Rock Art Painting

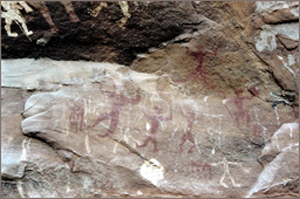

In the Pachmarhi Hills most of the paintings are from the Chalcolithic to the Historical period. Conflict is one of the main themes depicted during this time. War scenes are common but reasons for conflict are not indicated. Horsemen armed with swords and shields overlie the earlier paintings portraying the life of hunters and gatherers. They bear elaborate war equipment consisting of spears, axes, swords, shields, daggers and bows and arrows. Other individuals carry drums and trumpets, and foot soldiers as well as men riding caparisoned horses and elephants are depicted. Goats, dogs, oxen, donkeys and performing monkeys accompany the troops. The descendants of the original hunters and gatherers and artists of this region are the tribal Korku and Gond who still uphold some of the traditions of their ancestors. In the rock paintings their ancestors are depicted dancing in pairs or in rows and playing musical instruments. They hunted animals and collected honey from the hives of wild bees. Their mode of dress was quite simple. The women carried food and water and looked after the children. The forebearers of the present day tribal people had a variety of ways to express the magic of their beliefs, rituals and taboos. The tribes living in these hills have wooden memorial boards on which the carved horse and its rider is similar to those painted by their predecessors in the past on the walls of their rock shelters . They also decorate the walls of their houses and this activity seems to have its roots in the cave dwelling traditions of their ancestors. Men and horses of geometric construction are randomly spaced across the walls. Such paintings are done during the rainy season and on festive occasions, and bear a close resemblance to those found in the painted shelters.

Soldiers

Bees Nest

Presently, the wall paintings in their houses, as in the great majority of rock paintings, are executed in red and yellow pigments prepared from hematite or other iron oxides. The white pigment was made from limestone or kaolin, while mixtures of pigment that produce pinks are also found used in paintings. The rock paintings were executed in a number of stylistic conventions. Some are only sketches or constructs of lines, while others are silhouettes filled with colours and embellished with decorative designs.

ANTIQUITY OF PACHMARHI INDIA

Dr Meenakshi Pathak with her team in the Pachmarhi Hills

Considerable information is now available about the antiquity of Pachmarhi from Archaeological sources. The excavation by archaeologists in different shelters has provided sufficient archaeological data of the people who occupied these shelters. Excavations were conducted in rock shelters since 1932 by GR Hunter. He introduced the cave art of Pachmarhi in his lecture before the congress of the pre-proto historic science in 1932, which brought the painted rock shelters of Pachmarhi Hills to the notice of Lt Col DH Gordon. Hunter excavated here in 1932 and 1934-35 (Hunter-1955).

Cupules on Sand Stone

Clear evidence of Mesolithic culture has come from the Dorothy Deep shelter. The 1932 excavation was confined to the Nallah area, and a trial pit close to the rock wall up to 2’ and the 1934 excavation by a trial trench right across the breadth of the cave up to 5’ depth with undisturbed stratification. The earliest deposit was of the Mesolithic (Tardenoisian) period. The multiplicity of shapes and sizes, characteristic of most stone age cultures, suggests occupation prior to the Neolithic and the metal ages. Subsequently, the shelter was occupied by a culture using pottery. The excavator thought that though there was no sterile deposit between the two cultures, and quartz flakes were found in the upper layers where pottery abounds. It was doubtful if there was any overlap.

Three skeletons were found in association with the typical Tardenoisian flakes and implements but without any beads or other objects. Only two small pieces of cranium were found to be intact. Thus the following sequence has been worked out:

(a) The lower levels yielded microliths of flint. The absence of metal and polished stone indicated that these people lived before metal age. The tools used were mostly crescents and scalene Triangles as well as drills and scrapers.

(b) With no sterile deposit, the Dorothy Deep shelter was inhabited by the pottery using people.

(c) Of the three skeletons recovered from the Mesolithic deposit, two belonged to children of 6-7 and 11 years of age, while the third was an adult. Evidence of a hard diet and the sign of flattening and bowing of the thighbone were discernible. The teeth of the eleven-year-old child showed great deal of wear. The adult was muscular, with small teeth and jaws. There is no evidence to show that racially he differed from the modern people of this region (Collection with British Museum, London).

The excavation of 1935 followed the above sequence and attempted to establish the inference that the Palaeolithic man never inhabited the Mahadeo Hills. Divisible into three sub phases - upper, middle and lower. There was a definite cultural development during the Mesolithic age, in the technique of flaking, leading to the evolution of patterns more suited to the purpose. These tools are similar to those recovered from the Tardenoisian and Caspian sites in Europe and Africa (M.D. Khare 1984; 130). In 1950 A. Ghosh excavated Baniya Berry shelter where a trench of 22”X39” was dug and four layers were found. The lowest consisted of weathered sandstones and yielded no finds. Layer 3 - yellow brown soil mixed with stone chips, geometric microliths, pre pottery period. Layer 2 - of similar soil, also yielded geometric microliths. Layer 1 - top layer dark brown earth, no tools. This suggests the shelter was inhabited only during the Mesolithic period.

Then S K Pandey excavated two rock shelters in 1968. The first shelter was Jambu Dweep in which digging was barely 6 inches deep. It yielded small numbers both of microliths and pottery shreds. Another shelter, Baniya Berry, the excavation was in two distinct layers. The lower layer had loose sandy soil, with one large chalcedony piece, 2 Jasper flakes, 2 triangles and 28 chips. The upper layer of brown earth produced fluted cores and 4 parallel one-sided flakes. There was no pottery in this shelter.

Complex Hunting/Battle Scene

Panel with Figures & Monkeys

Depiction of Horses

Triangular Figures

Dancing Figures

Dancing Figures

During my field research work in the year 1990-91, I collected some Mesolithic pottery shreds, a few tiny pieces of bone and a pendent of the tooth of an herbivorous animal (monkey) from the loose surface of the shelters. Total finding of microliths: Trapeze - 1, blades - 34, side scraper - 8, and burins - 2.

Mesolithic technology, introduced from outside, supplemented the older technology with the passage of time. It consists of Mesolithic tools made of slender micro blade, which were first detached from cylindrical cores by a pressure technique and then blunted on one or more margins. These tools, made of fine-grained rocks, lime, chert and chalcedony, comprise blunted back blades, obliquely truncated bladed, points, crescents triangles and trapezes. By hafting them into bone or wooden handles, these tiny tools were utilized to make knives, arrowheads, spear heads and sickles. Colour nodules are also found in the loose surface. Yellow colour nodules have been found in Bori shelter.

The gradual developments of changes can be seen in this area regarding the use of fire and construction of floors of stone slabs. In the later phases the appearance of copper tools and pottery suggests contact between the Mesolithic people of shelters and Chalcolithic people of the plains. In the upper most layers, early historic pottery shows the persistence of Mesolithic way of life up to the historic times.

ABORIGINALS

Dr Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak and the Research Team

The population of Pachmarhi is principally tribal. The main tribes are Korku and Gond. The four-sub caste of Korku is Muwasi, Bawaria, Ruma and Bondoya. The word Korku means simple men or ‘tribesmen’. (Koru meaning 'man' and ku its plural). According to Korku, traditions of their origin, on the request of Ravana, Lord Mahadeo created two images of a man and woman from the clay of an anthill. He then infused life into these figures and they were called ‘Mula’ and ‘Mulai’, with a common surnames Pathre. These two were the ancestors of the Korku tribe. Korku are a Munda or Colarian tribe as their language belongs to the Mundari of Austro-Asiatic family. The Gond tribes speak Gondi language. The Gonds also call themselves ‘Ravanvasi’, meaning descendants of Ravana king of Lanka. Their legends suggest that they have migrated to the area from Andhra in the medieval period, and they speak a Dravidian language called Gondi. The Korkus consider themselves superior to Gonds. They would not take food from Gonds, but would not refused water and chilam (cigar).

Tribal Village

The average Korkus are well built & muscular. They have a round face, a nose rather wide, prominent cheekbone, a scanty mustache and his head shaved after the Hindu fashion. They are slightly taller than Gond (Russel and Hiralal 1969 : 552). They make houses of wattle and daub and with roofs made of handmade, baked clay tiles. The locals generally sleep on the ground and a few low stools carved from teak wood serve them as pillows. There is generally a verandah in the front of the house, a cattle shed attached to the side. The villages are kept remarkably clean.The interior of the house in Korku village is kept clean. The walls are decorated with various designs drawn on festive occasion, and the villagers take delight in pasting coloured pictures on the interior walls of their hut for decoration. Every villager has a few pigs and fowls about and both of which are eaten after being sacrificed. They are by no means particular about what they eat, fowls, fish, crabs and tortoise all consumed. Bondoya korku eat buffaloes too. The millets (kodu - kutki) are grown principally in the hilly tracks of trivial inhabitant, which form the staple food. Tobacco smoking and country liquor made by the local mahua flower is very common among these aboriginals. They often supplement their food with a number of edible fruits, tubers and honey collected from the forest. The tribal economy depends on agriculture.

Like most hill tribes the korku are remarkably honest and truthful. Korku consider themselves to be Hindus, and are held to have a better claim to a place in the social structure of Hinduism than most of the other forest tribes. They worship the Sun, Moon and also Mahadeo. The main festivals among Korku tribe are Shivaratri and Nagapanchami. Pachmarhi is the important pilgrim center for Shivaratri and Nagapanchami fares. The priests of Korku are of two kinds: ‘Parihars’ and Bhumka’. The Pariahs may be any man who is visited with the divine afflatus or selected as a mouthpiece by the deity. Parihars are also rare, but every village has it Bhumka, who perform the regular sacrifices to the village gods and the special ones entailed by disease or other calamities. The Korku have some belief in sympathetic magic as other primitive people. They also trust in Omens.

Korku tribe also has funeral rites. The dead are usually buried, the head pointing to the south. The earth is mixed with thorns while being filled in so as to keep off hyenas and stones are placed over the grave. Their family members and relatives honor the dead with carved and decorated teak wood memorial boards, placed under a sacred tree in the memory of the deceased during a highly religious ceremony. The primitive men in Hoshangabad district used painting as the chief source of amusement. Pachmarhi and Adamgarh hillock is the living monument of their art. The times have changed and there is a variety of means of amusement available to the people now.

CONTEMPORARY TRIBAL ART OF PACHMARHI INDIA

In the remote mountains, deep dense forests, swamps and deserts the lives of hunters and gatherer remained almost undisturbed, long after more advanced cultures settled in the valleys and lowlands. The tribal people living in the rock shelters observed the colonizing groups and recorded their activities in paintings on the walls of their rock shelters. Later, they were to adopt from the newcomers only few basic cultural items. This is the most complete record, supported by the evidence of archaeological remains, of the tribal culture, as it existed in the past.

Huge Shelter Occupied by the Local Tribes

Dr Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak with Local Tribe near Shelter

Tracing the Rock Art at the Nagdwari Cave

Over time the valley culture exerted greater influence on the tribal groups. They left the rock shelters and the painted record ceased. Although this occurred only a few hundred years ago, there exist only a few, more recent paintings, which may be linked to the earlier examples of rock art. The Korku honour their deceased members with carved and decorated teak wood memorial boards, which are placed under a sacred tree in their memories during the highly religious ceremony. This may last for seven to eight hours. During the ceremony the tribe females dance in a circle around the sacred mango tree. In between they hold the memorial board in their hands and dance.

Dr Meenakshi Dubey-Pathak with Tribal Couple

Memorial Board placed under a Sacred Tree

Memorial Board placed under a Sacred Tree

Following this the carved boards are venerated and wept over. Later, a goat or jungle fowl is sacrificed and eaten, while the local liquor made from the flowers of the Mahua tree (Bassia latifolia) is consumed. One such sacred tree is situated in the “Gond Baba Udhayan” (lit. - Garden of the Gond deity) located in the Pachmarhi town itself. Tribal people who come from the surrounding villages of Pachmarhi use this site for their religious rituals followed by feasts. Memorial boards are placed at the base of the sacred tree within ten years of a death. The subjects carved into the board are selected form a limited list of elements. These are usually horse riders; group of geometrical human figures holding hands, and representations of sun or moon and the name of the deceased.

In carvings of the horse and its rider the Korku do not depict their own ancestors, as they did not have horses. The figures mounted on horse represent their conquerors. This element of the carving is totally unrelated to the loves of the deceased, but its stylistic form and that of other human figures is similar to the more recent rock paintings situated in rock shelters only a few kilometers away (Wakankar and Brooks 1976: 16).

Women of the Tribe busy with their daily routine

Many of the present day tribal communities decorate the walls of their house with paintings. The selected subjects relate to their natural and cultural environments, depicting birds, floral patterns, whilst other appears to be of symbolic or ritual importance. These wall paintings also seem to have their roots in the rock art tradition. At present the Korku tribal live in wattle huts whose walls are coated by clay colored white. The tradition of paintings continues as the korku women decorated their house walls with paintings and sketches. They use local colour such as the dark or Indian red, yellow ochre, blue and white. The paintings are executed during the slack rainy season or occasionally during festival events. The women in the Korku society carry out all domestic work and look after the children.

The depiction of a peacock on the wall of a hut in the Kajri village situated 35 kilometers from Pachmarhi town is very similar to rock paintings found recently in the Langi Hill shelter . A symbol painted on the same repaired wall closely resembles a rock painting of the Swem Aam shelter that has only been recently explored. That the two traditions share the same roots can be seen in the common subject matter and the continuing stylistic conventions displayed by the contemporary art.

INDIAN ROCK ART : PACHMARHI THEMES

The subject matter in rock art can be very varied. The main subject everywhere is the animal or scenes of hunting them, which is the most common subject of rock paintings belonging to the Mesolithic and later periods. The subject matter of rock paintings also helps in studying many facets of human life. "The depictions of the species of animals, human and the food gatherers tell us much about the ecosystem in which they lived. The depiction of weapons, tools and other implements reveal their technical abilities. The illustration of his myths and beliefs bring back to our consciousness the essential aspects of out intellectual roots and displays the existential relationship between man, nature and the supernatural" (Anati-1980-20).

In the Indian rock paintings the presentation of man and animals is of almost the same standard although stylistically there are many differences (Mathpal 1980- 93). The artist did not represent everything he saw or knew. Besides animals and their hunters, there are other subjects depicted in rock art via social and cultural activities, ritual performances, domestic life and different images of women, such as mother with a child. In the early period human figures are rarely painted and the depiction is only symbolic and stick-shaped. Many human figures are conical animalized (Gordon 1960- 512), grotesque (Breuil and Lantier 1965- 187) and disproportionate (Bernguer 1973:40?45). In the rock paintings of Pachmarhi Hills prehistoric artists had depicted many cultural dimensions of their life and surroundings. Artists of early and later periods were greatly interested in the depiction of ritual dance and music. In the later period different types of musical instruments, battle scenes, soldiers, horse riders, symbols, patterns etc depicted them. The subject matter of the rock painting of Pachmarhi has been divided into the following categories: -

(a) Human forms. (b) Animal forms. (c) Scenes. (d) Material culture. (e) Mythology. (f) Nature. (g) Inscriptions.

HUMAN FORMS

Human beings are painted lesser realistically than the animals. There are total 2449 human forms belonging to all the periods in Pachmarhi. These forms have been divided into the following 30 sub-groups according to the subject matter: -

(a) Man. (b) Women. (c) Boy. (d) Girl. (e) Infant. (f) Hunter. (g) Fighter. (h) Rider. (i) Attendant. (j) Dancer. (k) Drummer. (l) Pipe Player. (m) Harp Player. (n) Cymbal Player. (o) Man with Mask. (p) Man with Kanvar. (q) Man with animal hide. (r) Women with sickle. (s) Man with axe or (Tree cutter). (t) Honey Collector. (u) Ritual performer. (v) Head Hunter. (w) Leader. (x) Mother Goddess. (y) Copulation. (z) Man in Hut. (aa) Anthropomorphic. (ab) Women engaged in domestic chores. (ac) Pregnant Women. (ae) Fragmented Figures.

Figures with Tiger

Archer

ANIMAL FORMS

Elephant

Normally animal forms part of a hunting scene. A good number of the large or medium size animal’s figures have been painted naturalistically. The common most details are their horns, snout and ears. The animal drawings of early period are very natural and more realistic than those belonging to the later period. In the earliest period the animals were depicted in considerable size, beautifully decorated with abstract and geometric patterns. There are nearly 1008 images of animals belonging to 25 different species. These species comprise Tiger, Leopard, Elephant, Wild buffalos, Bison, Oxen, Cow, Nilgai, Sambhar, Swamp deer, Wild boar, hyena, wolf Dog, Monkey, Horse, Pangolin, crocodile and probably a giraffe like long necked animal. Drawing of Porcupine, Rabbit and small creatures like Lizard, Scorpion and Fish are also found. Drawings of birds such as jungle fowl, peafowl and some ostrich like unidentified birds are also recorded. Some depiction of insects like centipedes and honeybees has also been found.

Goats

Monkeys

Bison with Lizard

Row of Cows

Ascetically Drawn Bison Panel

Hunters with Birds

• BIRDS

Total 37 drawings of a limited variety of birds have been found in various shelters in Pachmarhi Probably birds did not form major part of food but only an object of entertainment and curiosity in their surroundings and thus did not receive much significance in the lives of pre-historic men.

• MISCELLANEOUS

Different types of fish, turtles, scorpions, lizards, insects like centipede and honey bees have been depicted in different shelters.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36135

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Part 2 of 2

INDIAN ROCK ART : PACHMARHI THEMES

SCENES

Prehistoric artists have drawn all aspects of their life independently and complete in it. The artists depicted various compositions on the rock surface. Such compositions usually comprise scenes of hunting, food gathering, fighting, dancing, and music, social and daily chores.

Tree Ladder Scene

Figures with Monkeys

Dancers

Dancing Figures and Animals

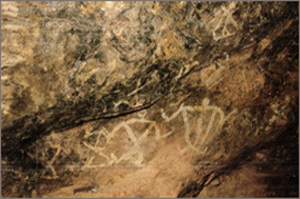

MATERIAL CULTURE - HEAD HUNTING SCENES

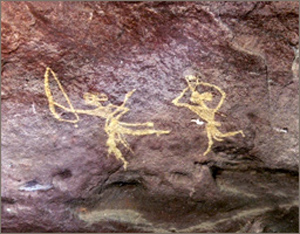

Headhunter

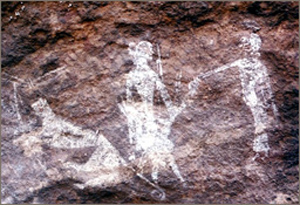

The subject of head hunting in the history of rock art is very uncommon. At present, in Indian rock painting its only the rock art of Pachmarhi which contain this unique depiction of head hunting. Peru in South America is the only other so far known place where scenes of head hunting are found (Bednarick 1989:73).

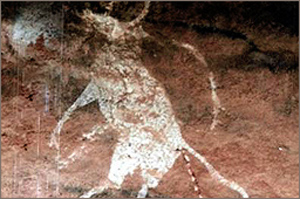

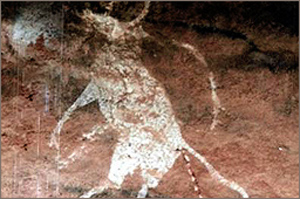

There are a total of seven depictions of headhunters, which have been first recorded by me. Executed in bichrome colour, these depictions belong to the historic period. The acts in these scenes depict the brutality prevalent in the society of the Stone Age man. The head hunting scene is very prominent in Lanji Hill shelter wherein a human figure is holding a human head in his right hand and shown running, yet looking back over his shoulder, perhaps anticipating a chase or ensuring himself of breaking contact with his enemy. A giant and robust figure measuring 3 ft in length and 2.5 ft in width executed in light red colour has been depicted which makes everyone curious . A headhunter with identical description as stated above, has been recorded at Swem Aam shelter.

In yet another depiction at Nagdwari shelter a headhunter decorated in red lines, perhaps his tattoo marks, has been shown carrying a well-dressed severed head . At Rajat Prapat shelter four human figures have been depicted as headhunters running in the same direction but at different distances. Drawn rhythmically and full of action, this scene is eye catching and gives an insight into the historic life.

Headhunters Running

Headhunters

Remarkably, all the drawings of headhunters are filled with white colour and outlined with red colour. The figures have sharp facial features and body proportionate. Headhunters were probably most respected perhaps because they ensured protection of the clan, group or community and achieved victory over their enemies. Hence, the figures of headhunters are often found well decorated with headdress, crown, earrings and bodies covered from waist downwards up to the knees. Every figure holds a severed head, which is well decorated with crown, earrings, headdress identical to its hunter, running in the same direction and same of fashion looking back over the shoulder. The act of beheading human beings was perhaps not a ritual as nowhere in the shelters any such scene has been depicted. It may be assumed considering the prevalent brutality that beheading may be a form of severe punishment to those who committed a heinous crime of transgressing the law of the land of the tribes. However, it is quite likely that the head of the enemy was severed to ensure annihilation and carried back home to confirm victory to own ground, clan etc. and displayed as a war trophy.

Indian history is replete with the instances of human sacrifice prevalent amongst the tribes in the country, particularly, by Gond and Korku tribes. The tradition of human sacrifice was alive in Mahadeo Hill. “In the days that are forgotten, human victims hurled themselves over the rock as sacrifice to the goddess Kali and Kal Bhairav, the consort and son of Shiva, the destroyer”. Capt J Forsyth has mentioned about an eyewitness account of an incident of human sacrifice at Mahadeo Hills in his famous book “The Highlands of Central India” (Forsyth J 1889:180-184).

MYTHOLOGICAL SCENES

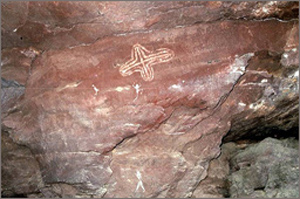

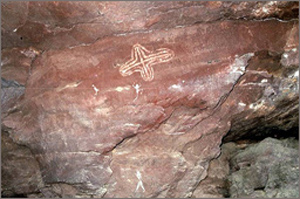

Tree Symbol Worship

The rock art suggestive of mythological origin is that of tree worship, cross worship, symbols of mother Goddess and demons. Gordon has commented that only a few Indian rock art paintings have a religious significance (Gordon 1958:109). “Symbols and so called signs found in rock paintings in different parts of the world are difficult to decipher. It is a code we have been unable to crack”, says Benerguer referring to European Ice Age symbols (Benerguer 1973:73). The paintings of Pachmarhi, which are likely to be related to mythology, have been grouped as follows:

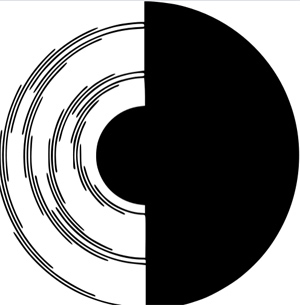

1. Mother Goddess 2. Tree Worship 3. Symbol 4. Cross Worship 5. Swastika 6. Labyrinth (chakra) 7. Geometrical figures 8. Superhuman or deity worship 9. Demons 10. Mythical Animals

INSCRIPTIONS

Writing of inscriptions on the walls of the caves and shelters is associated with Hermits and Monks living in isolation in early historic times. It was common practice in many hills and forest area inhabited by Hermits. These inscriptions do help us place paintings of historic period to certain chronological order. Two inscriptions both in Nagri script in Pachmarhi have been recorded. One is in Dorothy Deep and the other is in Mahadeo shelter. The inscriptions in Mahadeo are too faded to be translated but the inscriptions at Dorothy Deep are by far the most legible. It consists of two lines written in cremish white colour. The first line is obviously meant to be same as commencement of much longer second like. It would appear to be from Nagri of probably 11th to 12th centuries. The translation, which does not make any sense, is as follows: "Lenamasiya a vri vri Dha Dha Ve She Jai Jai".

INDIAN ROCK ART : ANALYTICAL STUDY

The Stone Age man has painted many aspects regarding the social, cultural, economical, religious and ritualistic, pertaining to his life on the bare and uneven rock surface. The surfaces in the caves and shelters have been formed naturally over a period of time. The depictions of contemporary flora fauna and domestic activities have also found their places in these paintings. The antiquity of these unique paintings was probably realised first time by Archibald and Carlleyle in 1867-68 when they discovered the first rock paintings in India at Sohagighat in Uttar Pradesh. Mainly amateurs have brought approximately 150 sites of the rock paintings to our attention. The archeologists never seem to appreciate the antiquity of these paintings. Hence due to lack of attention, this national heritage of our country is now subjected to vandalism. It is pathetic to see at some places where those paintings are near extinction due to lack of protective measures. The shelters in Pachmarhi are well known from tourist and archaeological points of view. But their historic, cultural, artistic, musical and dimensional aspects have been left uncovered totally by most of the researchers known to have worked here. Unlike in Bhimbetka, there are numerous shelters and painted shelters scattered all over the Pachmarhi Hills. The approaches to many shelters are difficult, dangerous and time consuming.

Considering Pachmarhi town as the hub there is hardly any direction where the paintings are not evident. The painted shelters are also found in the outer periphery of the Pachmarhi Hills in the Satpura ranges. The study of these shelters has not been done in my work; however, some references of these have been made here and there. I feel a separate study in a different time frame is needed for the detail study of such paintings. Therefore, I have confined my study to the painted rock shelters of Pachmarhi Hills only. I am hopeful that this work will be an authentic record of the paintings of Pachmarhi hills for the students of the rock art in the future. The present study is the first comprehensive and exhaustive record encompassing thematic and stylistic analysis of the rock paintings of Pachmarhi Hills.

METHODOLOGY