by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/20/21

We often hear of negroes who have learnt music, who are clerks in banking-houses, and who know how to read, write, count, dance, and speak, like white men. People are astonished at this, and conclude that the negro is capable of everything! And then, in the same breath, they will express surprise at the contrast between the Slav civilization and our own. The Russians, Poles, and Serbians (they will say), even though they are far nearer to us than the negroes, are only civilized on the surface; the higher classes alone participate in our ideas, owing to the continual admixture of English, French, and German blood. The masses, on the other hand, are invincibly ignorant of the Western world and its movements, although they have been Christian for so many centuries — in many cases before we were converted ourselves! The solution is simple. There is a great difference between imitation and conviction. Imitation does not necessarily imply a serious breach with hereditary instincts; but no one has a real part in any civilization until he is able to make progress by himself, without direction from others.* [In discussing the list of remarkable negroes which is given in the first instance by Blumenbach and could easily be supplemented, Carus well says that among the black races there has never been any politics or literature or any developed ideas of art, and that when any individual negroes have distinguished themselves it has always been the result of white influence. There is not a single man among them to be compared, I will not say to one of our men of genius, but to the heroes of the yellow races — for example, Confucius. (Carus, op. cit.)] What is the use of telling me how clever some particular savages are in guiding the plough, in spelling, or reading, when they are only repeating the lessons they have learnt? Show me rather, among the many regions in which negroes have lived for ages in contact with Europeans, one single place where, in addition to the religious doctrines, the ideas, customs, and institutions of even one European people have been so completely assimilated that progress in them is made as naturally and spontaneously as among ourselves. Show me a place where the introduction of printing has had results, similar to those in Europe, where our sciences are brought to perfection, where new applications are made of our discoveries, where our philosophies are the parents of other philosophies, of political systems, of literature and art, of books, statues, and pictures!...

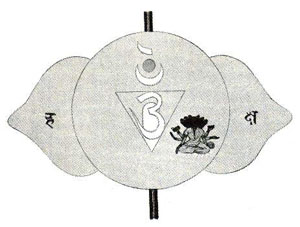

Owen's observations have, no doubt, considerable value; I would prefer, however, the most recent of the craniological systems, which is at the same time, in many ways, the most ingenious, I mean that of the American scholar Morton, adopted by Carus.* [Carus, op. cit., from which the following details are taken.] In outline this is as follows:

To show the difference of races, Morton and Carus started from the idea, that the greater the size of the skull, the higher the type to which the individual belonged, and they set out to investigate whether the development of the skull is equal in all the human races.

To solve this question, Morton took a certain number of heads belonging to whites, Mongols, negroes, and Redskins of North America. He stopped all the openings with cotton, except the foramen magnum, and completely filled the inside with carefully dried grains of pepper. He then compared the number of grains in each....

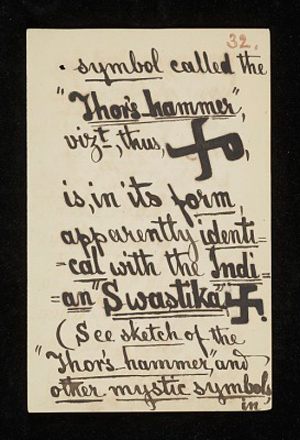

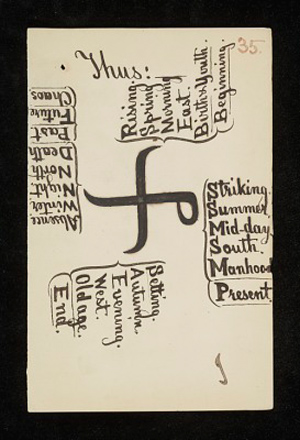

[Carus] likes to think that, just as we see our planet pass through the four stages of day and night, evening and morning twilight, so there must be in the human species four subdivisions corresponding to these. He sees here a symbol, which is always a temptation for a subtle mind. Carus yields to it, as many of his learned fellow-countrymen would have done in his place. The white races are the nations of the day; the black those of the night; the yellow those of the Eastern, and the red those of the Western twilight. We may easily guess the ingenious comparisons suggested by such a picture. Thus, the European nations, owing to the brilliance of their scientific knowledge and the clear outlines of their civilization, are obviously in the full glare of day, while the negroes sleep in the darkness of ignorance, and the Chinese live in a half-light that gives them an incomplete, though powerful, social development. As for the Redskins, who are gradually disappearing from the earth, where can we find a more beautiful image of their fate than the setting sun?...

We must mention another law before going further. Crossing of blood does not merely imply the fusion of the two varieties, but also creates new characteristics, which henceforth furnish the most important standpoint from which to consider any particular sub-species. Examples will be given later; meanwhile I need hardly say that these new and original qualities cannot be completely developed unless there has previously been a perfect fusion of the parent-types; otherwise the tertiary race cannot be considered as really established. The larger the two nations are, the greater will naturally be the time required for their fusion. But until the process is complete, and a state of physiological identity brought about, no new sub-species will be possible, as there is no question of normal development from an original, though composite source, but merely of the confusion and disorder that are always engendered from the imperfect mixture of elements which are naturally foreign to each other.

Our actual knowledge of the life of these tertiary races is very slight. Only in the misty beginnings of human history can we catch a glimpse, in certain places, of the white race when it was still in this stage — a stage which seems to have been everywhere short-lived. The civilizing instincts of these chosen peoples were continually forcing them to mix their blood with that of others. As for the black and yellow types, they are mere savages in the tertiary stage, and have no history at all.* [[Carl Gustav] Carus gives his powerful support to the law I have laid down, namely that the civilizing races are especially prone to mix their blood. He points out the immense variety of elements composing the perfected human organism, as against the simplicity of the infinitesimal beings on the lowest step in the scale of creation. He deduces the following axiom: "Whenever there is an extreme likeness between the elements of an organic whole, its state cannot be regarded as the expression of a complete and final development, but is merely primitive and elementary" (uber die ungleiche Befahigkeit der verschiedenen Menschheitstamme fur hohere geistige Entwickelung, p. 4). In another place he says: "The greatest possible diversity (i.e. inequality) of the parts, together with the most complete unity of the whole, is clearly, in every sphere, the standard of the highest perfection of an organism." In the political world this is the state of a society where the governing classes are racially quite distinct from the masses, while being themselves carefully organised into a strict hierarchy.]...

Is there also an inequality in physical strength? The American savages, like the Hindus, are certainly our inferiors in this respect, as are also the Australians. The negroes, too, have less muscular power;* [See (among other authorities), for the American aborigine, Martius and Spix, Reise in Brasilien, vol. i, p. 259; for the negroes, Pruner, Der Neger, eine aphoristische Skizze aus der medizinischen Topographie von Cairo, in the Zeitschrift der Deutschen morgenlandischen Gesellschaft, vol. i, p. 131; for the muscular superiority of the white race over all the others, Carus, op. cit., p. 84.] and all these peoples are infinitely less able to bear fatigue...

The negroid variety is the lowest, and stands at the foot of the ladder. The animal character, that appears in the shape of the pelvis, is stamped on the negro from birth, and foreshadows his destiny. His intellect will always move within a very narrow circle. He is not however a mere brute, for behind his low receding brow, in the middle of his skull, we can see signs of a powerful energy, however crude its objects. If his mental faculties are dull or even non-existent, he often has an intensity of desire, and so of will, which may be called terrible. Many of his senses, especially taste and smell, are developed to an extent unknown to the other two races.* [Taste and smell in the negro are as powerful as they are undiscriminating. He eats everything, and odours which are revolting to us are pleasant to him" (Pruner).]

The very strength of his sensations is the most striking proof of his inferiority. All food is good in his eyes, nothing disgusts or repels him. What he desires is to eat, to eat furiously, and to excess; no carrion is too revolting to be swallowed by him. It is the same with odours; his inordinate desires are satisfied with all, however coarse or even horrible. To these qualities may be added an instability and capriciousness of feeling, that cannot be tied down to any single object, and which, so far as he is concerned, do away with all distinctions of good and evil. We might even say that the violence with which he pursues the object that has aroused his senses and inflamed his desires is a guarantee of the desires being soon satisfied and the object forgotten. Finally, he is equally careless of his own life and that of others: he kills willingly, for the sake of killing; and this human machine, in whom it is so easy to arouse emotion, shows, in face of suffering, either a monstrous indifference or a cowardice that seeks a voluntary refuge in death.

The yellow race is the exact opposite of this type. The skull points forward, not backward. The forehead is wide and bony, often high and projecting. The shape of the face is triangular, the nose and chin showing none of the coarse protuberances that mark the negro. There is further a general proneness to obesity, which, though not confined to the yellow type, is found there more frequently than in the others. The yellow man has little physical energy, and is inclined to apathy; he commits none of the strange excesses so common among negroes. His desires are feeble, his will-power rather obstinate than violent; his longing for material pleasures, though constant, is kept within bounds. A rare glutton by nature, he shows far more discrimination in his choice of food. He tends to mediocrity in everything; he understands easily enough anything not too deep or sublime.* [Carus, op. cit., p. 60.] He has a love of utility and a respect for order, and knows the value of a certain amount of freedom. He is practical, in the narrowest sense of the word. He does not dream or theorize; he invents little, but can appreciate and take over what is useful to him. His whole desire is to live in the easiest and most comfortable way possible. The yellow races are thus clearly superior to the black. Every founder of a civilization would wish the backbone of his society, his middle class, to consist of such men. But no civilized society could be created by them; they could not supply its nerve-force, or set in motion the springs of beauty and action.

-- The Inequality of Human Races, by Arthur De Gobineau

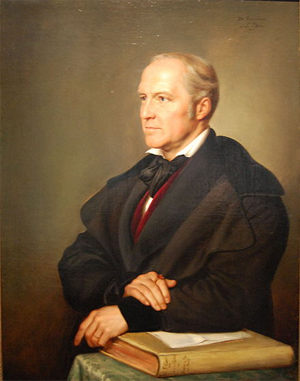

Carl Gustav Carus by Johann Carl Rößler

Carl Gustav Carus (3 January 1789 – 28 July 1869) was a German physiologist and painter, born in Leipzig, who played various roles during the Romantic era. A friend of the writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, he was a many-sided man: a doctor, a naturalist, a scientist, a psychologist, and a landscape painter who studied under Caspar David Friedrich.

Life and work

Carl Gustav Carus - Ruine Eldena mit Hütte bei Greifswald im Mondschein

In 1811 he graduated as a doctor of medicine and a doctor of philosophy. In 1814 he was appointed professor of obstetrics and director of the maternity clinic at the teaching institution for medicine and surgery in Dresden. He wrote on art theory. From 1814 to 1817 he taught himself oil painting working under Caspar David Friedrich, a Dresden landscape painter. Subsequently he studied under Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld at the Oeser drawing academy.

When the King of Saxony, Frederick Augustus II, made an informal tour of Britain in 1844, Carus accompanied him as his personal physician. It was not a state visit, but the King, with Carus, was the guest of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Windsor Castle, and Carus was able to visit many of the sights in London and the university cities of Oxford and Cambridge, and meet others active in the field of scientific discoveries. They toured widely in England, Wales and Scotland, and afterwards Carus published, on the basis of his journal, The King of Saxony's Journey through England and Scotland, 1844.[1]

The grave of Carl Gustav Carus, Trinitatis-friedhof, Dresden

He is best known to scientists for originating the concept of the vertebrate archetype, a seminal idea in the development of Darwin's theory of evolution. In 1836, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.[2] Carus is also noted for Psyche (1846).[3]

He developed a theory of landscape painting whose objective was the visualization of the inner workings of geological phenomena, which he called "Erdlebenbildkunst" (pictorial art of the life of the earth).[4]

Carl Jung credited Carus with pointing to the unconscious as the essential basis of the psyche.

Although various philosophers, among them Leibniz, Kant, and Schelling, had already pointed very clearly to the problem of the dark side of the psyche, it was a physician who felt impelled, from his scientific and medical experience, to point to the unconscious as the essential basis of the psyche. This was C. G. Carus, the authority whom Eduard von Hartmann followed. (Jung [1959] 1969, par. 259)

Carus died in Dresden. He is buried in the Trinitatis-Friedhof (Trinitatis Cemetery) east of the city centre. The grave lies in the south-west section, against the southern wall.

Family

His daughter Charlotte Carus married the artist Ernst Rietschel.

Carus, August Gottlob (1763-1842) (August 3rd, 1763, Dahme / Mark)

Relationships: Carus, Carl Gustav (1789-1869) [son]

-- August Gottlob Carus, by Kalliope Verbund

Born in Leipzig in 1789 as the son of the independent master dyer August Gottlob Carus, Carus attended the Thomas-Gymnasium here and began university studies in Leipzig in 1804. After initially attending scientific, medical and philosophical colleges, he decided in 1806 to study medicine exclusively and took lessons at the drawing academy at the same time. His studies were followed by an internship at the St. Jakobs Hospital and his work as a trainee in the practice of the obstetrician Johann Christian Gottfried Joerg (1779–1856).

-- Diseases of the urinary tract during the time of the Dresden doctor Carl Gustav Carus, by Albrecht Scholz, Sigrid Schulz-Beer

Chronology

1789 Carl Gustav Carus born in Leipzig on 3 January, only son of August Gottlob Ehrenfried Carus (1763-1842) and Christiane Elisabeth, née Jàger (1763-1846). His father rents and runs a small dyehouse just outside the city. Despite its modest circumstances, this artisan family has an illustrious circle of friends, including the publishers Christoph Gottlob Breitkopf, Gottfried Christoph Hàrtel, and Georg Joachim Goschen; the choirmaster of the Thomaskirche, August Eberhard Muller; the naturalist Wilhelm Gottfried Tilesius; and the musical writer Friedrich Rochlitz.

1801 Hitherto privately educated, Carl Gustav enters the celebrated Thomasschule in Leipzig, which he attends as a day student until 1804. On walking expeditions in the surrounding countryside with his drawing teacher, Julius Dietz (1770-1843), he makes studies of rocks, plants, and trees.

1804 With Dietz, Carus travels on foot to Dresden to visit the city's celebrated art museum, the Gemáldegalerie. On 21 April, Carus enters Universitàt Leipzig as a student of chemistry, physics, and botany, to which he later adds zoology, geology, and mineralogy.

1806 He transfers to medicine, probably on the advice of his distant relative Friedrich August Carus, the Leipzig professor of philosophy, and in view of the need to choose a profession. He studies anatomy under Christian Rosenmuller (1771-1820), and physiology under Karl Friedrich Burdach (1776-1847), who encourages him to investigate the central nervous system. He attends the drawing academy conducted by Johann Friedrich August Tischbein (the "Leipzig" Tischbein, 1750-1812) and by Veit Hans Schnorr (1764-1841). He strikes up a friendship with Johann Gottlob Regis (1791-1854), the future translator of Rabelais, Shakespeare, and Swift. While a medical student, Carus encounters the nature philosophy of Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775-1854) and of his follower, the philosopher and physician Lorenz Oken (1779—1851), author of the successful Lehrbuch des Systems der Naturphilosophie (Manual of the system of nature philosophy; 1809-11).

1809 Carus embarks on clinical training at the St. Jakob-Hospital in Leipzig under its director, J. Chr. L. Reinhold (1769-1809) and the surgeon J. Chr. A. Clarus (1774-1854). Then, J. Chr. G. Joerg (1779-1856), one of the founders of modern gynecology, invites him to join the maternity hospital in Leipzig.

1811 Carus graduates on 24 March as doctor of philosophy and master of liberal arts. In the same year he obtains his professorial qualification (Habilitation) in the faculty of philosophy and (on 11 October) a license to lecture (as Magister legens). He takes his doctorate in medicine on 20 December with a dissertation De uteri rheumatismo (On the rheumatic inflammation of the uterus). On 1 November Carus marries his father's stepsister, Caroline Carus (1784-1859). First essays in oil painting.

1812 Carus takes up teaching duties at the Universitàt Leipzig, giving classes in comparative anatomy.

1813 In charge of a French field hospital outside Leipzig during the "Battle of the Nations" Carus is horrified by the indifference of rulers to the slaughter of thousands. He catches typhus and fights for his life for three weeks. His physician and teacher Clarus gives him up for dead, but he recovers.

1814 Breitkopf und Hàrtel of Leipzig publish Carus's voluminous work Versuch einer Darstellung des Nervensystems und insbesondere des Gehirns nach ihrer Bedeutung, Entwicklung und Vollendung im thierischen Organismus (Essay on the nervous system, and the brain in particular, with reference to its importance, evolution, and maturation within the animal organism). He is offered a chair of physiology and anatomy at the German university in Dorpat (Estonia), and another at the Provisorische Lehranstalt fur Medizin und Chirurgie (Provisional school of medicine and surgery) in Dresden, combined with the directorship of the maternity hospital there; he moves to Dresden in the winter of 1814 to 1815.

1815 Confirmed as professor at the Kôniglich-Sàchsische Chirurgisch-Medicinische Akademie (Royal Saxon surgical and medical academy). Inaugural address at the official opening of the Akademie in August 1816. In Dresden, Carus visits the landscape painter and etcher Johann Christian Klengel (1751-1824), who encourages but also disappoints him. Begins to write the Nine Letters on Landscape Painting (this is the date given in the first edition; in the Lebenserinnerungen he gives the date as circa 1816: Carl Gustav Carus, Lebenserinnerungen und Denkwurdigkeiten, 3 vols. [Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1865—66], 1:181).

1816 Death of Carus's son Ernst Albert, of scarlet fever. First submission to the art exhibition of the Dresden Akademie: four paintings. Probably in 1816 or thereabouts, Carus has his first contact with Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840), which leads to a close friendship lasting some ten years. Carus visits Abraham Gottlob Werner (1750-1817), inspector and instructor of mining and mineralogy in the Bergakademie (Mining academy) at Freiberg in the Erzgebirge.

1817-18 Carus visits Berlin for the first time.

1818 Carus publishes his Lehrbuch der Zootomie (Manual of zootomy) and sends a copy to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832). Goethe and Carus begin to correspond; both become members of the Kaiserlich-Leopoldinisch-Carolinische Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher (Emperor Leopold-Carolingian German academy of naturalists) at Halle an der Saale, founded in 1652. The Norwegian landscape painter Johan Christian Clausen Dahl (1788-1857) arrives in Dresden to pursue his studies and makes the acquaintance of both Friedrich and Carus.

1819 Carus makes a journey to the Baltic coast (with Friedrich's example in mind) and visits Friedrich's brothers at Neubrandenburg and Greifswald; visits the island of Rugen and the chalk cliffs of the Kónigsstuhl. On this trip, Carus makes sixty-two drawings.

1820 Carus publishes the two-volume Lehrbuch der Gynákologie, the first manual of gynecology ever published in Germany; the book makes Carus famous and goes into five editions. He visits Carlsbad, where he meets the philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling (1775-1854) before traveling on to Prague and Zittau. At Caspar David Friedrich's suggestion, he hikes along the crest of the Riesengebirge. The celebrated Danish sculptor Berthel Thorvaldsen (1770-1844) visits Carus in Dresden on his way from Warsaw to Vienna.

1821 Carus meets with Goethe in person, for the only time in his life, in Weimar on 21 July. Carus is traveling to Switzerland on his way to visit Italy for the first time; the trip takes him as far as Genoa. On 12 September Carus climbs Mont Anvert, in the Massif du Mont-Blanc; he draws the mountain and later produces a painting based on his drawings. Carus meets the writer and translator of Shakespeare, Ludwig Tieck (1773-1853); from 1824 onward he will regularly take part in readings in Tieck's home.

1822 In February Carus sends to Goethe all that he has so far written of Letters on Landscape Painting: letters I, II, III, and V, together with three illustrations or sketches for illustrations for his projected scientific treatise on primitive portions of the bone and shell skeleton. Receives royal appointments as a court counselor and medical counselor. Delivers a commemorative lecture at the Gesellschaft deutscher Naturforscher und Àrzte (Society of German naturalists and physicians), which he has founded jointly with Lorenz Oken (1779-1851): Von den Anforderungen an eine kunftige Bearbeitung der Naturwissenschaften (On the requirements of the future practice of the natural sciences).

1823 Carus publishes an essay, "Grundzuge allgemeiner Naturbetrachtung" (General principles of the observation of nature), in volume 2 of Goethe's periodical Zur Naturwissensckaft uberbaupt, besonders zur Morphologie (On natural science in general and morphology in particular).

1824 In Uber Kunst und Altertum (On art and antiquity) Goethe discusses the geognostic landscapes exhibited by Carus in Weimar in September. Carus completes Letters on Landscape Painting (letters VI through IX).

1825 In August, visits Berlin.

1826 Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859) pays his first visit to Carus in Dresden. Henceforth, he will always stop over to see Carus when traveling in the suite of the king of Prussia, Friedrich Wilhelm III, to Bad Teplitz in Bohemia. Carus begins work on the Zwôlf Briefe über das Erdleben (Twelve letters on earth life), published in 1841. In the Kunst-Blatt, edited by Ludwig Schorn, Carus publishes one of Letters on Landscape Painting (letter VIII).

1827 Death of King Friedrich August of Saxony. The new King Anton (1755-1836) appoints Carus "Hof- und Medicinalrath" (Court and medical counselor), and Carus joins the Collegium (council of government). He retires from teaching and from the directorship of the Leipzig maternity hospital. As court physician he enjoys greater financial independence and more free time; he intensifies his activity as a scientist and as a writer. Carus publishes his discovery of the circulation of the blood in insect larvae.

1828 Carus publishes Von den Ur-Theilen des Knochen- und Schalengerüstes (On the primitive portions of the bone and shell skeleton). He declines a professorial appointment in Berlin. Second visit to Italy (Florence, Rome, Naples, Paestum) in the company of Crown Prince Friedrich August. In Rome, he meets with Thorvaldsen and is introduced to the German artistic colony. His friendship with Friedrich is under a cloud, the consequence—according to Carus—of Friedrich's "confused mental state."

1831 First edition of Nine Letters on Landscape Painting published by Gerhard Fleischer, Leipzig.

1832 After Goethe's death on 22 March 1832, Carus paints his Goethe Memorial; or, In Memory of Goethe: Landscape Fantasy, aiming to complete the painting by 28 August (Goethe's birthday).

1833 Carus succeeds Johann Gottlieb von Quandt (1787-1859) as president of the Dresdner Kunstverein, remaining in office until 1842. In November Carus purchases Villa Cara, a large house with gardens in the eastern suburbs of Dresden (destroyed in 1945).

1834 The French sculptor Pierre-Jean David d'Angers (1788-1856) comes to Dresden to make a bust of Tieck. He also executes a profile relief of Carus. Carus takes him to see Friedrich. Deeply impressed, David d'Angers buys a number of paintings from Friedrich. Carus gives him a number of his own paintings, receiving in return a number of statuettes and a plaster cast of David's bust of his own revered authority, the naturalist Georges de Cuvier (1769-1832).

1835 In August Carus travels via Koblenz, Mainz, and Metz to Paris, where he meets with Alexander von Humboldt. The second edition of Letters on Landscape Painting, with an additional, tenth letter, is published in Leipzig by Gerhard Fleischer. Under the same imprint, Carus brings out his Reise durch Deutschland, Italien und die Schweitz imjahre 1828 (Journey through Germany, Italy, and Switzerland in the year 1828).

1836 Death of King Anton. Friedrich August II ascends the throne. Carus publishes (again in Leipzig) his journal of a journey to the Rhine valley and to Paris. Alexander von Humboldt visits with Carus in Dresden; they discuss Zwôlf Brief e über das Erdleben and Humboldt's related undertaking, Kosmos: Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung (Cosmos: Notes for a physical description of the world).

1839 Carus attends the opening ceremony of the Leipzig-Dresden railroad.

1840 Death of Caspar David Friedrich, in depression and poverty. Carus publishes an obituary in Kunst-Blatt, followed by a commemorative essay in the following year.

1841 Third visit to Italy: Carus spends two months in Florence as personal physician at the court of the duke of Tuscany. Zwôlf Briefe über das Erdleben published in Stuttgart.

1844 Tour of England and Scotland, including the Isle of Staffa (Inner Hebrides) and Fingal's Cave. In the following year, Carus publishes an account of the trip, England und Schottland im Jahre 1844. He takes up the study of phrenology, or cranioscopy, on which he subsequently publishes a number of works.

1845 The first volume of Alexander von Humboldt's Kosmos: Entwurf einer physischen Weltbeschreibung appears, the last of the five volumes being published in 1862.

1846 Carus's Psyche: Zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Seele (Psyche: On the developmental history of the soul) published in Pforzheim. Carus regards this as his most important work of psychology. In it, his own prophetic impulses and the "divinity of [man's] inmost being" lead him to the hypothesis of reincarnation on a higher plane. Carus embarks on his memoirs, Lebenserinnerungen und Denkwürdigkeiten, which occupy him until 1856 (published in three volumes by Brockhaus in Leipzig, 1865-66).

1853 Carus publishes Die Symbolik der menschlichen Gestalt: Ein Handbuch zur Menschenkenntnis (The symbolism of the human form: A manual of knowledge of humanity), in which he first defines the module (primordial measure or Urmafi) of one-third of the length of the spinal column.

1854 Follows this with Die Proportionslehre der menschlichen Gestalt; zum ersten Male morphologisch und physiologisch begründet (Theory of the proportions of the human form; now for the first time explained in morphological and physiological terms), in which he develops and modifies the theory of the module (Urmass) put forward in Johann Gottfried Schadow's Polyclet (1834), with a view to providing artists with "a truly practical scale of measurement" (einen wirklich praktischen Masstab).

1859 Deaths of Carus's wife, Caroline, and Alexander von Humboldt. Carus publishes an article in the Nova acta Leopoldina entitled "Über Begriff und Vorgang des Entstehens" (On the concept and process of emergence); simultaneously, Charles Darwin in London publishes his book On the Origin of the Species by Means of Natural Selection, which sweeps away all competing theories of evolution.

1861 Carus's magnum opus of nature philosophy, Natur und Idee; oder, Das Werdende und sein Gesetz (Nature and idea; or, becoming and its law), is published in Vienna by Wilhelm Braumüller.

1862 Carus is elected president of the Kaiserlich-Leopoldinisch-Carolinische Deutsche Akademie der Naturforscher in Halle, where in 1864, to mark his fifty years as a professor, a Carus foundation is set up and a medal awarded (as it is to this day).

1863 Carus publishes the last of his many writings on Goethe: Goethe, dessen Bedeutung fur unsere und die kommende Zeit (Goethe, his meaning for our time and for time to come).

1865 Carus's memoirs, Lebenserinnerungen und Denkwurdigkeiten, are published in 3 volumes, 1865-66.

1867 Carus retires from medical practice. In Dresden, he publishes his last book: Betrachtungen und Gedanken vor auserwahlten Bildern der Dresdner Galerie (Observations and thoughts on selected paintings in the Dresden Gallery).

1868 Carus becomes honorary president of the Gesellschaft deutscher Naturforscher und Arzte, founded by him and Lorenz Oken in 1822. In his speech he once more voices his opposition to positivist science.

1869 Death of Carl Gustav Carus on 28 July at his home, Villa Cara, in Dresden; he is buried on 31 July in the Trinitatisfriedhof, Dresden-Johannstadt.

-- Nine Letters on Landscape Painting, with a Letter from Goethe by Way of Introduction, by Carl Gustav Carus, translated by David Britt

Botanical Reference

The standard author abbreviation Carus is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.[5]

Written works

Carl Gustav Carus by Julius Hübner

Memory of a Wooded Island in the Baltic Sea (Oak trees by the Sea)

Zoology, entomology, comparative anatomy, evolution

• Lehrbuch der Zootomie (1818, 1834).

• Erläuterungstafeln zur vergleichenden Anatomie (1826–1855).

• Von den äusseren Lebensbedingungen der weiss- und kaltblütigen Tiere (1824).

• Über den Blutkreislauf der Insekten (1827).

• Grundzüge der vergleichenden Anatomie und Physiologie (1828).

• Lehrbuch der Physiologie für Naturforscher und Aerzte (1838)- also medical

• Zwölf Briefe über das Erdleben (1841).

• Natur und Idee oder das Werdende und sein Gesetz. 1861.

Medical

• Lehrbuch der Gynekologie (1820, 1838).

• Grundzüge einer neuen Kranioskopie (1841).

• System der Physiologie (1847–1849).

• Erfahrungsresultate aus ärztlichen Studien und ärztlichen Wirken (1859).

• Neuer Atlas der Kranioskopie (1864).

Psychology, metaphysics, race, physiognomy

• Vorlesungen über Psychologie (1831).

• Psyche; zur Entwicklungsgeschichte der Seele (1846, 1851).

• Über Grund und Bedeutung der verschiedenen Formen der Hand in veschiedenen Personen (About the reason and significance of the various forms of hand in different persons)(1846).

• Physis. Zur Geschichte des leiblichen Lebens (1851).

• Denkschrift zum 100jährigen Geburtstagsfeste Goethes. Über ungleiche Befähigung der verschiedenen Symbolik der menschlichen Gestalt (1852, 1858).

• Über Lebensmagnetismus und über die magischen Wirkungen überhaupt (1857).

• Über die typisch gewordenen Abbildungen menschlicher Kopfformen (1863).

• Goethe dessen seine Bedeutung für unsere und die kommende Zeit (1863).

• Lebenserinnerungen und Denkwürdigkeiten – 4 volumes (1865–1866).

• Vergleichende Psychologie oder Geschichte der Seele in der Reihenfolge der Tierwelt (1866).

Art

• Neun Briefe über Landschaftsmalerei. Zuvor ein Brief von Goethe als Einleitung (1819–1831).

• Die Lebenskunst nach den Inschriften des Tempels zu Delphi ( 1863).

• Betrachtungen und Gedanken vor auserwählten Bildern der Dresdener Galerie (1867).

Travel

• Sicilien und Neapel (1856).

Translations

• Carus' translation of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Paradise, Canto I. at academia.edu

Art gallery

The Colosseum in Moonlight

The Imperial Castle

In Memory of Sorrento

View of Dresden at Sunset

Barge Trip on the Elbe near Dresden

Balcony Room with a View of the Bay of Naples , 1829 or 1830.

Italian Moonshine (Rome, St. Peter's in Moonshine)

Tintern Abbey

Italian Fishermen in Port

Sailboat

Full Moon near Pillnitz

Woman on the Balcony

Stoane Age Mound

The Studio Window

See also

• Philosophy of the Unconscious (von Hartmann)

• List of German painters

References

1. C.G.Carus, The King of Saxony's Journey through England and Scotland, 1844, english edition, London, Chapman and Hall, 1846

2. Ellenberger, Henri F. (1970). The Discovery of the Unconscious: The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry. New York: Basic Books. pp. 207. ISBN 978-0-465-01672-3.

3. Whyte, Lancelot Law (1960). The Unconscious before Freud. New York: Basic Books. p. 148.

4. https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digit ... 0/id/71300

5. IPNI. Carus.

Sources

• Jung, C.G. ([1959] 1969). The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious, Collected Works, Volume 9, Part 1, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01833-2.

• "Carl GustavCarus", Art History: Romanticism

• Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Carus, Karl Gustav" . Encyclopædia Britannica. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne. Missing or empty |title= (help)

External links

• Media related to Carl Gustav Carus at Wikimedia Commons

• Caspar David Friedrich: Moonwatchers, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which contains material on Carl Gustav Carus (no. 10-11)

• German masters of the nineteenth century: paintings and drawings from the Federal Republic of Germany, a full text exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, which contains material on Carl Gustav Carus (no. 11-12)

• Carus, Carl Gustav (1848). Mnemosyne. Pforzheim: Flammer und Hofmann.

• Carl Gustav Carus' translation of Dante Alighieri's Paradise, canto I, at academia.edu

***************************

Carl Gustav Carus (1789–1869)

by Encyclopedia.com

Accessed: 3/20/21

Carl Gustav Carus, a German physician, biologist, and philosopher, was born in Leipzig and studied chemistry and then medicine at the University of Leipzig. In 1811 he became the first person to lecture there on comparative anatomy. Two years later he became director of the military hospital at Pfaffendorf and, in 1814, professor of medicine at the medical college of the University of Dresden, where he remained to the end of his life. He was appointed royal physician in 1827 and privy councilor in 1862.

Carus was widely known for his work in physiology, psychology, and philosophy, and was one of the first to do experimental work in comparative osteology, insect anatomy, and zootomy. He is also remembered as a landscape painter and art critic. He was influenced by Aristotle, Plato, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph von Schelling, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, about whom Carus wrote several works, the most important of which is Goethe dessen seine Bedeutung für unsere und die kommende Zeit [Google translate: Goethe whose meaning for our and the coming time] (Vienna, 1863). Carus's philosophical writings were more or less forgotten until the German philosopher and psychologist, Ludwig Klages, resurrected them.

Carus's philosophy was essentially Aristotelian in that it followed the unfolding or elaboration of an idea in experience from an unorganized multiplicity to an organized unity. This universal, unfolding unity or developing multiplicity within unity Carus called God. God, or the Divine, is not a being analogous to human intelligence; rather, it is the ground of being revealed through becoming, through the infinitely numerous and infinitely varying beings or organisms that come into being through the Divine in space and time.

Carus called his theory of a divine or creative force "entheism." The unknown Divine is revealed in nature through organization, structure, and organic unity. As the ground of being, it is outside space and time, unchanging, and eternal. As thought or insight, it is the God-idea of religion, found everywhere in life and the cosmos. As life, it is the sphere, the basic form taken by living cells and the heavenly stars. As matter, it is the ether exfoliating in infinitely varied things.

According to Carus, the body cannot be separated from the soul. Both are soul, but we speak of "body" when some unknown part of the soul affects the known part; and we speak of "soul" when the known part affects the unknown part.

Carus's metaphysics, and his important contribution to psychology, is a theory of movement from unconsciousness to consciousness and back again. Whatever understanding we can have of life and the human spirit hinges upon observation of how universal unconsciousness, the unknown Divine, becomes conscious. Universal unconsciousness is not teleological in itself; it achieves purpose only as it becomes conscious through conscious individuals. Consciousness is not more permanent than things; it is a moment between past and future. As a moment, it can maintain itself only through sleep or a return to the unknown.

***************************

Carl Gustav Carus, the first director of the newly established maternity institute of the Dresden Royal Surgical-Medical Academy 1814-1827

by B. Sarembe

1989

Abstract

Carl Gustav Carus was born in 1789 in Leipzig. He studied at the University of Leipzig. His specialization in Gynecology and Obstetrics took place at the Triersches Maternity Hospital. In 1814 he was named Professor for Obstetrics in Dresden at the Royal-Surgical-Medical-Academy. He was the head of the Maternity Hospital till 1827. Under his direction many midwives, students and physicians were educated. He published numerous articles and books on medical and philosophical-psychological topics. He was a talented artist of the Romantic especially in painting landscapes. He was a friend of Caspar David Friedrich and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. After 1827 he was the physician in ordinary to 3 saxonian kings. He died in 1869. The Medical Academy in Dresden bears his name "Carl Gustav Carus" since its foundation.