by Gillian Evison

Indian Institute Librarian

December 2004

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

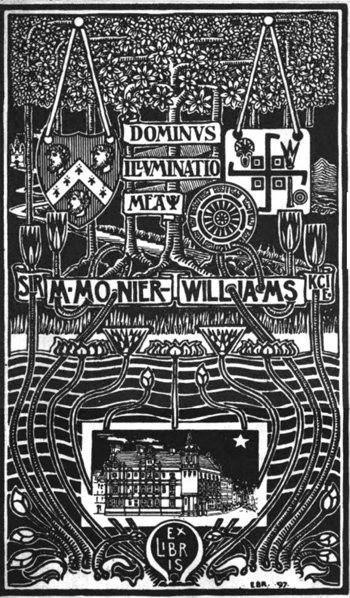

The Indian Institute Library on the top floor of the New Bodleian and the building of the old Indian Institute, now the home of the History Faculty Library and the James Martin 21st Century School, are the surviving remnants of an ambitious research institution set up in 1884 by the Boden Professor of Sanskrit, Sir M. Monier-Williams dedicated to the learning and literature of India. Some traces of the former use of the building remain and both the Sanskrit inscription inside the front door and the elephant weather vane on the roof bear testimony to the Indian Institute’s former life as a centre for Indian studies. The majority of the rarest 18th and 19th century publications in the Bodleian’s South Asian collections have bookplates showing that they were originally part of the Institute’s library, giving some idea of the wealth of printed resources available to members of Sir Monier-Williams’ research institution before the dispersal of its library, museum and teaching staff to various other locations in the University in the 1960s.

The end of the Indian Institute was controversial and continues to be so to this day, as became clear not so long ago in the letters section the Michaelmas 2003 edition of the magazine Oxford Today.1 The previous issue had featured a brief article by Alastair Lack entitled India and Oxford which had described the Indian Institute building as an emblem of Oxford’s interest in the sub-continent. Clearly intended as a feel-good nostalgic article for Oxford alumni, it had left Ranjit Singh feeling anything but good or nostalgic. He wrote:

“If anything, the building is a symbol of the disgraceful betrayal of trust the University displayed towards its friends and supporters in India. My family was amongst the donors inveigled by the University and the then Boden Professor of Sanskrit, Sir Monier Monier-Williams, privately to raise funds in India to construct the Institute. It was to be, in Monier-William’s words, ‘an everlasting symbol of amity’ between Oxford and India.

Despite its undertakings, the University forced the Indian Institute out of its home in 1968 and into the sterile New Bodleian Library library to make way for University administrative offices. Even when the administration abandoned the building, instead of being returned to its rightful occupants it was turned over to the Modern History faculty, which of course focuses on European history.

That the University should act in this way is bad enough. That it should now proudly cite the Institute’s building as indicative of its attitude towards its supporters in India is simply appalling.”

In this paper I will be looking at the history of the Institute from its optimistic beginnings as a colonial centre of instruction about all things Indian to its disintegration under the pressures of battles for real estate and changes in the way that the University thought about its teaching of Indian subjects.

As Ranjit Singh’s letter states, the Indian Institute was the brainchild of the Boden Professor of Sanskrit Sir M. Monier-Williams whose portrait can be seen on the staircase leading to the present library on the top floor of the New Bodleian.

Sir M. Monier-William's appointment to the Boden Professorship was somewhat controversial. He was born in India in 1819, where his father was Surveyor General, but returned to England as a child when his father died. He entered Balliol College but feeling no vocation for the church, for which his family had intended him, he left before taking his degree in order to enter Haileybury College and prepare for service with the East India Company as a writer. He trained for the service at the college from January 1840, and he passed out head of his year. It was whilst at Haileybury that he started to study Sanskrit, little knowing that it was form the substance of his future career. When his youngest brother died in action in an unsuccessful attempt to relieve the beleaguered fort of Kahun in Sind, he acceded to his widowed mother’s request to stay in England and gave up his plans for a career in India. He returned to Oxford but Balliol would not take him back so he entered University College in 1841 to read Classics and Mathematics in which he only managed to obtain a double Fourth Class degree2. His degree results undoubtedly suffered from his continued pursuit of Sanskrit, which he studied under the first Boden Professor Horace Hayman Wilson. In 1843 he won the Boden Sanskrit scholarship and after graduating in 1844 was immediately appointed professor of Sanskrit, Persian, and Hindustani at Haileybury, a post that he held until 1858, when the college was closed in the wake of the Indian mutiny and the teaching staff were pensioned off.

The closure of Haileybury left him searching for another opening and the vacancy for prestigious and highly paid Boden Professor of Sanskrit after the death of Horace Hayman Wilson in 1860 proved providential. Boden Professors at this time were elected by all the M.A.s of the University3 and as Convocation had 3,7864 members the election was contested as if the protagonists were prospective members of Parliament. Monier Williams spent over £10005 on manifestos, handbills, letters to newspapers and personal canvassing in a closely fought election against the German scholar Max Müller.

The Sanskrit Chair had been founded by Colonel J. Boden for “the conversion of the Natives of India to the Christian Religion”6 and Max Müller felt himself well qualified for the post. He secured the support of leading scholars, including Edward Pusey and John Keble. Max Müller may have had the support of the majority of Oxford scholars but he unfortunately suffered from two major handicaps; he was a German on friendly terms with Oxford theologians of the liberal movement with “Germanist” tendencies, which made his theology suspect to the conservatives in the church. Monier Williams may not have had the reputation in the field of Sanskrit that Müller enjoyed but he had the important advantages of being English by birth and well known as a devout evangelical Anglican.

The battle for the Professorship was long and nasty. Supporters of Müller sought to raise doubts about William's competence as a Sanskrit scholar. One of the Boden scholars Robinson Ellis circulated a paper in which it was claimed that he could not read a Sanskrit manuscript7 and when evidence was produced to the contrary it was claimed that it merely proved that:

"Mr. Williams is able to recognize the letters of a Sanskrit MS when he can compare it with an existing text. This is a kind of mechanical labour which is paid for at the public libraries at Paris and Berlin at the rate of half a crown a year"8.

In retaliation Monier Williams claimed that Müller's area of speciality was a backwater and not relevant to the purpose for which the Boden Professorship had been set up. He claimed that his own area of speciality, the epics and sacred law, were the real Hindu scriptures while the Rig Veda, Müller's speciality, was a "curious monument of bygone worship, at which the missionary, more usefully engaged in studying the present condition of the Hindu mind would content himself with a rapid glance"9.

The support of scholars at Oxford was not enough to carry the vote for Müller when the Convocation was held on 7th December 1860. Large numbers of evangelical country clergy appeared in Oxford to cast their votes and Monier Williams was elected with a majority of 223 out of a total of 1433 votes recorded. The unfortunate Robinson Ellis, the Boden scholar who had questioned Monier William’s knowledge of Sanskrit was required by statute to attend lectures by the new Boden Professor. Monier Williams described their first encounter as one in which, “his whole demeanour was that of a person who would have welcomed an earthquake or any convulsion of nature which would have opened a way for him to sink out of my sight.”10 Monier Williams, however, was determined to be gracious in victory and was largely successful in winning his former opponents over, with the notable exception of Max Müller who resisted all efforts at reconciliation.

At his inaugural lecture Monier Williams set out the evangelical agenda which had carried the day for him.

“A great Eastern empire has been entrusted to our rule, not to be the theatre of political experiments, nor yet for the sole purpose of extending our commerce, flattering our pride, or increasing our prestige, but that a benighted population may be enlightened, and every man, woman, and child … hear the glad tidings of the Gospel.”11

In his view India, of all British possessions, was the most inviting and interesting for the missionary. It was not a country of savage tribes who would melt away before superior force and intelligence of Europeans but the home of a great and ancient people. These inhabitants traced back their origin to the same Aryan stock as the Europeans and had attained a high degree of civilization when Europeans were still barbarians. India had had a polished language and literature when English was unknown. It was for Europeans, indebted to this ancient civilization, to unearth the fragments of truth, buried under superstition, error and idolatry and to help India return to its former place amongst the foremost nations of the earth. He had to acknowledge that it was unlikely that missionaries would ever encounter Hindus who could understand Sanskrit but nevertheless, loyal to the beliefs of the Chair’s founder, stoutly maintained it was the key to understanding Hindu civilization.

In addition to his evangelical agenda, Monier Williams had not forgotten his days as the Professor of Sanskrit, Persian, and Hindustani at Haileybury. He began to see the possibilities afforded by Oxford for filling the educational vacuum that had been left by the closure of the East India Company College. As he was later to describe in the lecture How can the University of Oxford best fulfil its duty towards India12, Indian Civil Service Probationers were selected by an annual competitive examination for 17 to 19 year olds. About forty were selected out of two to three hundred candidates and during two years of probation were expected to sit a number of examinations in London. During the period of probation they were expected to reside in one of eight Universities approved by the Secretary of State for India, namely, Oxford, Cambridge, London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Aberdeen, St. Andrew’s and Dublin. Whilst at the University, they were subject to University discipline but not under formal academic supervision of any kind. In Monier William’s view, the fact that they simply resided at University but did not take any University examinations meant that they gained little from their experience of University life. The unsatisfactory support for I.C.S probationers was particularly visible at Oxford as its proximity to London made it an extremely popular choice for residency.

In addition to the unsatisfactory support for I.C.S. probationers, Indian students had started coming to England and were mostly studying without supervision. Among those in Oxford about half had no College attachments and Monier Williams felt there was a grave risk that after being cast adrift in England Indian students would return home deteriorated in character rather than improved.

In 1875 he persuaded Congregation to pass three resolutions: first that arrangements be made for I.C.S. probationers to reside at the University; second that University teachers should be appointed in certain branches of training required by them: and third that the B.A. degree be brought within their reach.

In order to provide a stable study environment for both I.C.S. probationers and Indian students, he formally proposed the foundation of an Indian Institute at a Congregation held on May 13th 1875. The purpose of the Institute was to form a centre of teaching, inquiry and information on all subjects relating to India and its inhabitants. It was to restore among the I.C.S. probationers the old community spirit of the East India Company's College at Haileybury and would promote the welfare of Indians in Oxford. In addition it would propagate a general knowledge of India among Oxford's ordinary students some of whom might go on to exercise control over India's destiny in Parliament. Before the advent of submarine telegraphy, district officials had a great deal of autonomy but with swifter communication channels, London government had an opportunity to interfere, for good or ill, as never before. As Monier Williams tactfully remarked in his speech at the opening of the new Institute “the interposition of an all-powerful Assembly, acting with the best intentions, but not always according to knowledge, is apt to cause administrative complications.”13

The new Institute was to have lecture rooms, staff rooms, accommodation for Indian students and visitors and a library which was to "offer for daily use a collection of Indian manuscripts, books, maps, and plans, many of them too rare and costly to be procurable by private means. Its Reading-room will be supplied with all kinds of Indian newspapers and periodicals, some of them in the native languages.14 "The Institute was also to have a Museum that was to present a typical collection of specimens which would give a concise synopsis of the country and its material products, its people and their moral condition. Monier Williams sought to reassure Congregation that the sole purpose of this Institute was to be the prosecution of Oriental research and not to attract “mere sight-seers, curiosity-hunters, and excursionists”.15

The Boden Professor was not alone in his vision of a centre that would combine teaching, a museum and library for the benefit of I.C.S. probationers and the educated classes in England and India. In the same year J. Forbes Watson, the Director of the India Museum, which was sharing cramped and unsatisfactory quarters in the attics of the India Office with the India Library, proposed the construction of a purpose built Indian Institute on a vacant site belonging to the India Office in Charles Street.

The London Indian Institute, however, never progressed beyond a proposal and in the 1880’s the India Museum was amalgamated with the growing collections of Indian craft objects at the South Kensington (later Victoria and Albert) Museum. While the London proposal was based on the solid foundation of existing library and museum resources, Monier Williams had nothing. Any fund raising campaign would have to cover museum and library stock and a place to put them well as suitable salaries for staff.

Monier Williams’ first trip to India was a success. He held meetings in the major cities in the north including Bombay, Calcutta and Delhi, explaining his proposal and asking for aid. The Prince of Wales, who was at the time in India, pledged his support, along with Lord Northbrook, the then Governor-General, and many members of the Civil Service. A number of Indian princes were also persuaded to join the subscription list. A second trip in the South of India and Ceylon followed towards the end of 1876 in which he was to receive similar encouragement. In addition to official support and money, he also received gifts of books, manuscripts and objects for the proposed new museum and library. Monier Williams followed his two Indian trips with a series of lectures and addresses in London and Oxford. In these he promulgated his vision of Indian studies becoming part of every University curriculum and the creation of a number of Institutes devoted to the dissemination of correct information on Indian matters, of which Oxford’s proposed Indian Institute was to be but the first.

The fund raising campaign received further momentum with the official approval and support of Queen Victoria and the royal princes.

In Oxford the Master and Fellows of Balliol were particularly sympathetic to Monier William’s great enterprise. It was Benjamin Jowett, Master of Balliol who offered every candidate who passed the I.C.S. examination a place in Balliol and it was Balliol College Library that provided a temporary home for the books and manuscripts that had been collected for the new Institute. Initially it was planned that the Institute itself would be part of Balliol16 but Jowett had made himself unpopular by attaching too many of the staff appointed by the University to his college and the idea was abandoned in favour of making it a University institution. In his book Oxford and Empire Richard Symonds suggests that the Indian Institute would have had a better chance of development had it been attached to Balliol.17 Certainly it is likely that Balliol would have been prepared to make up some of the shortfall in running costs which quickly became apparent after its opening. A college-based Institute might also have received stronger academic direction, and been prevented from sliding into the government club about which Edward Thompson was to be so scathing in the 1930’s.

The Institute began its life in rooms hired at no. 8 Broad Street, opposite to Balliol College but in 1880 Convocation approved the plan for an Indian Institute and granted a site in the Parks along with an Endowment of £250 per annum from the University Chest, payable from the date of its opening.

Max Müller objected to the money that Monier-Williams had raised being spent on new buildings. He circulated a flyleaf to Congregation urging that premises could be found on existing University property and that the donations should fund research and fellowships. He later wrote:

"What all the Indians say is that rich Oxford University went around with a hat, promised to help Indian students, and all the money they subscribed in India was spent on bricks and stuffed animals18."

Max Müller’s general antipathy to Monier Williams was no doubt partly at the root of this campaign. Monier Williams had tried to invite Müller’s to join an Oxford committee for the Institute using as his intermediary, Benjamin Jowett, the Master of Balliol, who remained friendly with both men, but this appeal had fallen on deaf ears.19 Leaving personal animosity aside, however, Max Müller had a valid point. When the building was finally been completed, of the £33,869 11 shillings that had been raised only £235, 7 shillings and 10 d remained to be handed over to the Curators for the continued running of the Institute. This was to provide woefully inadequate support and from the outset there was never going to be sufficient money to support a scholarship programme.

There was considerable opposition to the new Institute being built in the Parks and negotiations were then started with the Fellows of Merton College who consented to part with a site in Broad Street for the sum of £7,800. The Prince of Wales laid the foundation stone of the building in 1883, acting with full Masonic ritual, and the University statute governing the Institute was passed in 1884.

The building, consisting of lecture rooms, a library and museum, was not completed until 1896 since some of the site was held by leaseholders and the leases did not come up for renewal until 1892. Monier Williams had to raise more money to purchase this land from Merton College and managed to secure the £1400 needed from Sir Bhagvat Sinhjee, Thakur of Gondal. The architect was Basil Champneys with the carving being executed by a Mr. Aumonier.

The style was intended to suggest the purpose of the building by the introduction of Indian forms in the fauna and flora of the carvings and some richness of detail without departing from the type of the 17th century English Renaissance.

At the very first recorded meeting of the Indian Institute Curators on Nov 5th 1884 the third item on the agenda was a discussion about the insufficiency of endowment of £250 per year and the problem of under-funding appears with monotonous regularity in the minutes from then on.

Of the three components of Monier William’s Indian Institute, the museum was probably the least successful. In the words of John Harle and Andrew Topsfield’s book on Indian art in the Ashmolean museum, it is described as a story of “the high minded, even sanctimonious, late Victorian ambitions of its founder over-reaching themselves and being gradually nullified by the inertia or sheer lack of funds of his successor”.20 As a largely ethnographic museum of economic products and crafts, it was clearly inspired by the new Indian Museum in South Kensington, which had been formed through the amalgamation of the old East India Company Museum in Whitehall and the collections of Indian craft objects at the South Kensington Museum. In common with the prevailing opinion of the time, while Monier Williams held a deep regard for India’s literary tradition, he had scant regard for Indian art other than its craft traditions. In a third Indian fundraising tour undertaken in the winter of 1883-1884 he took time to visit the International Exhibition in Calcutta and secure some items as well as enlisting the help of various regional authorities to collect representative local objects and ship them to Oxford.

It was left to civil servants and museum officials to interpret this brief as they thought best. A manuscript volume held in the Ashmolean lists the objects collected for Monier Williams between 1883 and 1885. They vary from the eccentric, such as the three blown crocodile eggs and granite stone for scrubbing elephants from Travancore to highly professional selections from the most knowledgeable experts of the day, such as the collection of several hundred examples of handicrafts chosen by the Madras Museum.

When the completed Indian Institute was finally opened the museum installation was carried out by Dr. H. Lüders assisted by Mr. Long of the Pitt rivers Museum, with the aid of a grant from the University.21 The Indian Institute Library has a number of archival photographs, which must have been taken soon after and show a space crammed full of wooden cases, rugs on the floors and walls and costumed dummies.

An entrance corridor contains several small stupas from Bodhgaya, a model of emperor Hamayun’s tomb and a couple of stuffed yaks.

As in so many other aspects of the Indian Institute, the lack of financial provision soon told. There was no money to support a full time curator so its direction was left entirely in the hands of the Boden Professor of Sanskrit. Apart from the fact the Boden Professor had many other duties, appreciation of India’s linguistic and literary achievements rarely went hand in hand with an appreciation of Indian art. The minutes of the Indian Institute Curators show how the museum was from the first the poor relation of the Institute’s library. Apart from acceptance of donations from ex-I.C.S. officers and old India hands, there was little consistent policy concerning the museum in the years that followed Monier William’s death in 1899. In 1909, Lord Curzon, the Chancellor of the University, issued a confidential note, preserved in the Indian Institute archives, which recommended the ending of the museum. The collection was meagre and ill-assorted in comparison with that at South Kensington, and worse still was visited by more women than men, which he viewed as a sufficient grounds for closure and in his words, “a pathetic commentary upon Sir M. Monier-Williams’s assurance that it was not intended to attract “mere sight-seers, curiosity-hunters and excursionists”.22

The month following, the Curators resolved on a policy of gradual dispersal of the museum collections but, perhaps because of the effort involved in such a wholesale dispersal, little was done. In 1926 the museum was still in existence, the Curator’s minutes recording that the visitors were mainly school children and Americans. The stuffed animals, to which Max Müller had referred in his condemnation of the Indian Institute some thirty years earlier, were, however, disposed of in 1926, having been a regular committee item since the museum’s opening due to their poor state of preservation and bad smell, which by that time was being described as “positively injurious.” The Curators did later try and interest the Pitt Rivers in the entire museum collection but the proposal was refused due to lack of space. Some select items were accepted, however, including the collection of Jaipur arms and armour that had been gifted by the Maharajah. The museum rallied briefly under the Keepership of Prof. E.H. Johnston from 1937-42. By this time there was a greater appreciation of the Indian fine art tradition and Johnston was responsible for the purchase of some fine examples of Mathura sculpture including the beautiful head of Siva, now in the Ashmolean’s Eastern Art Museum. During the Second World War, however, the museum was closed and in 1945 the Curators were not inclined to re-open it. In 1946, a solution to the Indian Institute’s white elephant appeared in the form of Dr. William Cohn, a distinguished war-time refugee from Berlin, who suggested the amalgamation of the museum collections with the Ashmolean’s Chinese ceramic collections in a new Museum of Eastern Art. The Museum opened in the Indian Institute in 1949 and remained there until its move in 1962 to the Ashmolean’s newly established Department of Eastern Art. It seems that no one was sad to see it go. Aongst the many letters of protest I have read about the closure of the Indian Institute I have yet to find any opposition to the museum’s move to the Ashmolean site.

While the founder of the Institute’s philological and literary interests ensured that the Library received more attention from the Curators than the Museum its financial situation was no better and it relied on inadequate grants and donations. The two biggest donors of books to the library were Monier-Williams himself, who gave his own library of between 3 and 4000 volumes, and the Rev. Solomon Caesar Malan who donated his collection of about 4000 books to the Institute.

Much of Malan's library was inappropriate to a centre for Indic studies; his collection included works on Patristics, the history of the Eastern Church and grammars and dictionaries in over 100 languages. Although attempts were made to rehouse them the conditions of Rev. Malan's bequest made it difficult to do so and most remained in the Indian Institute until it became possible to disperse them among the Bodleian collections after the library came under Bodleian administration.

The first Indian Institute Librarian was a Dr. Schönberg, who was also to assist Prof. Monier-Williams in the preparation of his Sanskrit-English dictionary. He was appointed on Nov 11th 1884 at a salary of £50 a year besides living, lights and rooms. It was agreed that his duties should be to reside in the building, to take charge of the books in the library and objects in the museum. He was to sit in the library when engaged in work on the dictionary and he was to devote two hours a day to cataloguing books. His contract was terminated by March of the next year and from then on Indian Institute Librarians seem to have had very limited tenure. The longer a Librarian was in post the more likely it was that he would ask for an increase in wages. The Curators’ way of managing such requests can be demonstrated by the case of the unfortunate Mr. Hartley, Dr. Schönberg's successor, whose contract was abruptly terminated on Dec 15th 1885 after he had applied for an increase in salary.

The lack of continuity in the Librarian's post and the haphazard acquisition of gifts did not help the development of the collection and one gets the impression that over time the Curators of the Indian Institute found management of the Library increasingly irksome. In the minutes of a meeting held on Nov. 13th 1924 the Keeper complains that although there is an assistant as well as a chief librarian, he often finds that neither of them are to be found in the library. Then in 1925 there was the matter of 30 books from the Malan collection, which a Mr. A.S. Domiack from Wadham had removed from the library without signing for them. These books had subsequently been offered for sale to a book dealer who luckily noticed the Indian Institute stamp and returned them.

On Oct. 26th 1926 Dr. Cowley, Bodley's Librarian, approached the Curators of the Indian Institute with a proposal that the Bodleian should take over the management of the Indian Institute Library. Unfortunately the typewritten and printed papers which outline the proposal are missing from the minutes book so it is not clear what benefits that Dr. Cowley felt the Bodleian would gain from connecting itself with the Indian Institute. The Curators of the Indian Institute came to an agreement in which they paid the Bodleian £275 per annum to connect the Indian Institute Library with the Bodleian as a special department for Indian studies. Dr. Cowley took over management of the library in 1927 and while the Librarian remained to assist him the assistant librarian was replaced with a Bodleian employee. The Curators of the Indian Institute seem to have done rather well out of the deal because by 1928 Dr. Cowley is complaining that the administration of the Indian Institute Library is by no means covered by their contribution and has involved a considerable expenditure from Bodleian funds. It is interesting that despite the early administrative take over by the Bodleian, it is the Library that seems to have come to symbolize the Indian Institute and form the substance of the 1960’s dispute which is still remembered today.

The academic programme for the Institute was initially ambitious and inclusive. In his the opening ceremony lecture of 1884 Monier Williams described how the Institute had already appointed a number of teacher in Indian subjects and was able to offer one Indian classical language, Indian Law, History, and Political Economy23. Oxford was still missing the Honour School of Oriental Studies that he had proposed in 1875 but this became a reality in 1886, the year in which he was also knighted, taking the name Sir Monier Monier-Williams (presumably because he thought it sounded more impressive than plain Sir Monier Williams). The Institute’s academic programme was intended to be the first step in a process whereby Oxford and other Universities would eventually take over the entire process of educating and examining Indian Civil Service Probationers. The teaching programme would also answer the needs of the future doctors, lawyers and missionaries of the university who would end up working in India.

The academic programme was intended to go hand in hand with the interchange of knowledge that would naturally arise from mixing young Englishmen with Indians studying in England. Monier Williams saw the young Indians gaining active dynamic qualities such as courage and determination while the young Englishmen would learn passive qualities such as patience and obedience to authority.24 At Oxford the corrosive influence of Indian philosophy to treat action as a mistake leading to future rebirths would be eradicated and Indian students would learn that work was part of religion.

In the early days of the Institute, however, there were insufficient Indian students to provide the kind of counterbalance to the I.C.S. probationers that Monier William’s rosy vision of an East West interchange of moral qualities required. An attempt to secure six Government scholarships for visiting Indian scholars had failed because the Secretary for India overruled a promise made to Monier Williams by the Viceroy, being disinclined to single out Oxford University for special favour25. In an article that appeared in the Oxford and Cambridge undergraduate journal of May 10, 1883 the author knew of only three native Indians in Oxford and did not believe there could be more than a dozen.26 On the other hand there were some 50 I.C.S. probationers at the time of the Institute’s foundation.

The Honours School in Indian studies was short-lived and came to an end in Monier-William's own lifetime. It failed to take off as a popular alternative to Classics for those contemplating careers in India and interest was confined to those had already decided to make India their career, namely the I.C.S. probationers. After a change in the age limits of the Indian Civil Service made it no longer possible for the I.C.S. probationers to stay in Oxford for more than a year, the Honours School was no longer viable.27

Richard Symond’s in his book Oxford and Empire suggests that it was the strong I.C.S focus of the institute, coupled with a decline in interest in Sanskrit, the subject of its ex-officio Keeper, that was to prove its eventual undoing as a centre for Indian studies.28 I.C.S. probationers no longer studied Sanskrit and Classical studies, which had provided a steady stream of students attracted by the relationship of the language to Latin and Greek, started to decline from the 1920’s onwards. Between 1921 and 1930 only four candidates sat for honours in Sanskrit and in 1931 there had been no candidate for the Boden Sanskrit scholarship for six of the eight previous years. The opportunity offered by the growing status of Modern History as a subject was missed with a series of appointments to the Reader in Indian History who were distinguished by their propagation of the government line rather than by their original thought. Sir Geoffrey Corbett, appointed in 1932 actually continued in the I.C.S. during his first two years of appointment. Even E.H. Johnston the Boden Professor Sanskrit from 1937-42 was a retired I.C.S. man. It is small wonder that the Indian students who visited the Institute to read the newspapers saw it as a nest of I.C.S. spies.

An attempt to rejuvenate the Indian Institute was made by the Secretary of the Rhodes Trust, Lord Lothian, while he was Parliamentary secretary for India from 1931-32. He suggested that Edward Thompson, who had come to Oxford to teach Bengali to the I.C.S. probationers and who had undertaken a number of visits to India on behalf of the Rhodes Trust, use the Indian Institute as the base for some of his suggested initiatives. These included prizes and Fellowships for Indian writers and scholars that would encourage them to come and lecture at Oxford. Lord Lothian also suggested the appointment of an Indian administrator or deputy administrator to the Institute, whose prime role would be to arrange for eminent Indian scholars visit Oxford. Had this happened the subsequent history of the Institute might have been very different. Thompson’s response, however, was that the Institute was lost and damned beyond redemption its so called Indian studies being utilitarian and governmental and its appointments being mainly political.29 The only solution in his view was to close it all down, sell the building to a college and begin again with a new “Irwin House” which would house a library, accommodation for distinguished visiting Indians and provide lectures untainted by I.C.S. associations.30 Even with the prospect of money from the sale of the old Institute, it would have been a costly enterprise and nothing ever came of plans to raise funds for a new “Asia House” to be modelled on Rhodes House with library containing all the books from the Bodleian on the living East, a Warden, theatre and museum.

I.C.S. probationers ceased to come to Oxford after the start of the Second World War in 1939 and in the post-war years the Indian Institute came under unwelcome scrutiny from the University Chest, which was in need of further accommodation. The Indian Institute Curators in 1947 allowed the University Land Agent to take over three rooms on the ground floor, claiming that no more could be offered as all other accommodation was needed by the Institute for its own purposes. It is clear from the minutes of Curators' meetings, however, that Indian Institute rooms were being put to uses that had nothing to do with Indian studies. A Chinese lending library was set up in Indian Institute accommodation and the Institute was also storing Turkish books on behalf of the Faculty of Oriental studies.

The Oriental Faculty, as shown by its use of Indian Institute rooms, desperately needed further accommodation and it was proposed that a new Oriental Institute should be set up near the Ashmolean Museum. It was suggested that the Indian Institute should cease to exist and that the Indian Department and library should become part of the new Oriental Institute, much to the dismay of classical Indologists such as V. Raghavan who declared that such a move would be ruinous to Indian studies at Oxford31. In 1955 the Hebdomadal Council passed a decree to establish the Oriental Institute, which was to include "full provision for Indian studies." In the Congregation debate, Mr. H.T. Lambrick, Fellow of Oriel College, spoke against the proposal. He did not object to an Oriental Institute but protested that the inclusion of Indian studies would mutilate the Indian Institute and that it would be the story of Naboth’s vineyard all over again.32 G.R. Driver, Professor of Semitic Philology spoke for the motion. He suggested that the Indian Institute may have been responsible for the decline in Indian studies at Oxford in the last 20 years and assured Congregation that the successors of those who gave money to found Institute had been consulted and were not unfavourable to the proposals for the Oriental Institute. The decree was passed. A further resolution was then passed to lift restrictions on the use of the Indian Institute to University purposes any spare accommodation in the Indian Institute exclusive of the library, galleries and rooms already occupied by persons whose work required proximity to the library.33 The Indian Institute Library was to be allowed to remain because Bodley's Librarian and Curators had adamantly opposed the move of Bodleian material away from the central site and won general support for their position.

In 1956 the University obtained a High Court order allowing it to use the site and buildings of the Indian Institute as general property of the University in consideration of a fund of £20,000 set up as a permanent endowment for the promotion of Indian studies. To begin with it appears that the plan was to reconstruct part of the building and adapt it for the use of the University Chest at the same time extending library space by putting a floor in the Malan room and then allowing the library to take over the space to be vacated by the museum when it moved to the Ashmolean. However, it is clear from the minutes of the Indian Institute that after the 1956 court order the University Chest was exerting considerable pressure on the Curators to take over areas that were in use by members of the Indian studies department. In 1958 there was an attempt to take over the lecture room and the Curators decided at a meeting on Feb 20th that there was a need to maintain constant vigilance against further manoeuvres by the Chest.

In 1960 the plan seems to have become a more ambitious proposal to knock down the old building put up an entirely new structure on the Indian Institute site for the use of the University Offices.

It appears that accommodation for the Indian Institute Library did not figure as part of the plan and that the Indian Institute books were expected to be absorbed into the stacks of the Bodleian. On May 25th 1961 the Curators of the Indian Institute Library decided that the Keeper of the Indian Institute should write to the Registrar stating that they considered it most important that the Indian Institute Library should be maintained as a separate entity and not absorbed into the general collections of the Bodleian. A letter followed this to the editor of the Oxford Magazine pointing out that the library had been attracting an increasing number of students from many different faculties and arguing that it was imperative that the Library remained as a working unit.

In 1964 the Hebdomadal Council started discussing a proposal with Curators of the Bodleian, which was to result in one of the University's most notorious episodes of bloodletting in recent history. The proposal was that the Bodleian, which was badly in need of further accommodation, should be offered the Proscholium, to serve as a main entrance and the Divinity School for an exhibition room. In addition the Indian Institute Library was to be moved from the Indian Institute building to a roof extension, which was to be built on the north range of the new Bodleian and joined to deck B, which would be used for open shelf Indian Institute material.

The Indian Institute building would then be assigned to the Central Offices for redevelopment from the date of the completion of the roof extension. In return for the reduction of stack space that the Bodleian would suffer by incorporating Indian Institute material it was to be offered the underground area between the Clarendon Building and the Old Bodleian for excavation of new stack areas.

In June 1965 two contentious debates were held on the future of the Indian Institute site. K. Ballhatchet, Reader in Indian History, led the opposition. He argued that the Franks commission had yet to make its recommendations on future provision for the University's administrative requirements. It was therefore not sensible to make provision for administrative offices on the Indian Institute site when the future shape of the administration had yet to be decided. D. Pocock, the Reader in Indian Sociology said that treating India as a branch of Oriental studies failed to reflect equal numbers of research students from other disciplines such as Modern History, Anthropology, Geography and Agriculture and Forestry. He felt that to ally Indian studies so closely with Oriental studies gave a wrong impression to those outside Oxford of the Universities interests in South Asia. It was argued that the Indian Institute site should not only retain the library but also provide rooms to allow for the development of a proper South Asian Regional Studies centre such as had just been set up by Cambridge.

Bodley's Librarian J. Myres was in a difficult position. University procedure meant it was impossible for him to oppose the Indian Institute proposal without causing the whole decree to be rejected. He had suggested the plan for taking over the Proscholium and Divinity school himself and objected to the way that Council had tacked on to it a proposal which he considered totally unacceptable. If he supported Ballhatchet the Bodleian could lose space, which it desperately needed. He proposed to vote against Ballhatchet but only on the grounds that he did not wish to abandon his plans for the Proscholium and the Divinity school. He did, however, declare his intention, in open opposition to the Curators of the Bodleian, of voting for the deletion of the clauses concerning the Indian Institute at a later date.

When the decree was brought before Congregation on June 15th, Ballhatchet and Pocock proposed an amendment that the clauses concerned with the removal of the Indian Institute Library to the roof of the Bodleian be replaced with clauses stating that any redevelopment of the Indian Institute site should provide for the rehousing of the Library on the site with adequate room for expansion.

At the close of the debate, Ballhatchet's amendment to the decree was rejected by 38 votes and the decree was carried by 55 votes. Since the decree had achieved a majority of less than two thirds it had to go to Convocation, the body of all the M.A.s of the University. The voting was again close and the decree was carried by a mere 18 votes. A Times article of June 30 1965 suggested that the narrow victory was due to Hertford College, which hoping for a share in the site of the Indian Institute, had invited all its M.A.'s to come and vote in return for a free lunch.

Throughout the series of debates, the Boden Professor Thomas Burrows made no contribution although without a doubt he opposed the removal of the Indian Institute Library to the top of the Bodleian as his name appears on Ballhatchet's flysheet outlining the amendment for the debate on the 15th June. One cannot but speculate what effect he would have made, as Monier-William's direct successor, had he chosen to speak in support of the Reader in Indian History.

The press reaction in India was unfavourable and Mr. M.C. Chagla, the Indian Education Minister expressed official concern to the British High Comissioner in Delhi. The Reuter report of the meeting in the Times, suggests that the concern centred around the move of the library rather than the demolition of the building.34 On Dec 31st Bodley's Librarian J. Myres resigned and Ballhatchet and Pocock both left Oxford to take up posts at SOAS and Sussex University. Before giving his papers to the Bodleian, Myres unfortunately weeded them so no reference remains to this episode but his strong feelings on the matter can be guessed from an article, which appears in the March issue of the Oxford Magazine in 1968. For the supreme irony is that having fought so desperately for the use of the Indian Institute site the University decided to transfer the whole University Office complex to Wellington square. As Myres drily remarks:

"Had they reached this obvious conclusion two years ago, as they were strongly urged from many sides to do, it would have saved one or two of us, who found it impossible to reconcile Council's previous policy with the best interests either of the administration or of the Bodleian, some measure of inconvenience."

The obvious solution might have been to leave the Indian Institute Library where it was but as Myres writes:

"so innocent a notion is quite alien to our administrative proprieties. Money has been allocated for moving the Indian library out of the Indian Institute, and on this move, however, senseless, that money must now be spent".

The move went ahead as Myres predicted and the Indian Institute building became the Modern History Faculty. when the History Faculty moves from this site, it is interesting to speculate what battles may be re-fought for possession of the building. Not so long ago I had a phone call from a Hertford college representative seeking to verify whether there was any archival proof of a promise made to the college that it had first refusal on the building should it ever be vacated…

I will finish with the letter in Oxford Today with which I started this talk. It represents what could be described as the popular history of the Indian Institute and one that I have heard told by librarians and scholars from all over the world. In the popular version, the Institute takes a simplified form, just a building and a library, which together symbolize enduring British-Indian friendship and a golden age of Indian Studies in Oxford, brutally torn asunder by an uncaring University. As I hope I have shown, the real the story of the Institute is more complex and troubled. The seeds of its destruction, namely an over ambitious vision, lack of money, and the focus on a narrow sector of the student population were present from the day it opened its doors. While its demise was not inevitable, it is not as surprising as it might seem to those who have only encountered the popular version of the Institute’s history. Monier Williams would have been gratified to see the affection in which his expensive bricks and mortar are held today and one cannot but admire his achievement in creating a library, museum, and teaching centre from nothing. Had the Institute had more Keepers of his entrepreneurial flair it might still be in existence today serving students and researchers of the University where once it trained Civil Servants for the Empire.

Gillian Evison Indian Institute Librarian December 2004

_______________

Notes:

1 Oxford Today 15:3, Michaelmas 2003, p. 62

2. Richard Symonds Oxford and empire : the last lost cause? Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1986 p. 107

3. Richard Gombrich On being Sanskritic : a plea for civilized study and the study of civilization. Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1978 p.8

4. Nirad Chaudhuri Scholar extraordinary : the life of Professor the Rt. Hon. Friedrich Max Müller, P.C. London : Chatto & Windus, 1974 p. 221

5. Symonds p. 107

6 The Times Wed Dec 22 1830. Notice of the election of the Professorship of Sanskrit in the University of Oxford.

7 Monier Williams. Notes of a long life’s journey Unpublished memoir (copy held in the Indian Institute Library, p. 379

8. Chaudhuri p. 228

9. Chaudhuri p. 223

10 Monier Williams. Notes of a long life’s journey Unpublished memoir (copy held in the Indian Institute Library, p. 379

11 Monier Williams A study of Sanskrit in relation to missionary work in India; an inaugural lecture delivered before the University of Oxford, on April 19, 1861. London : Williams and Norgate, 1861, p. 59-60

12 Monier Williams How can the University of Oxford best fulfil its duty towards Oxford? Lecture given at the opening of the Indian Institute and reported in the Oxford & Cambridge Undergraduates Journal, Oct 16 1884

13 Ibid.

14 A record of the establishment of the Indian Institute in the University of Oxford : being an account of the circumstances which led to its foundation. Oxford : Compiled for the Subscribers to the Indian Institute fund, 1897 p. 4

15 Ibid.

16 Balliol College Minute Book (25 June 1878 and 9 Nov 1878)

17 Symonds p. 109

18. Symonds p. 110

19 Monier Williams. Notes of a long life’s journey Unpublished memoir (copy held in the Indian Institute Library, p. 498

20 J.C. Harle & Andrew Topsfield Indian art in the Ashmolean Museum (Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1987) p. x

21 Ibid. p. xii

22 Lord Curzon The Indian Institute printed confidential note, 25 March 1909, bound in Minutes, v. 2

23 A record of the establishment of the Indian Institute in the University of Oxford : being an account of the circumstances which led to its foundation. Oxford : Compiled for the Subscribers to the Indian Institute fund, 1897 p. 42

24 Ibid.

25 Symonds p.111

26 Oxford review: the Oxford & Cambridge Undergraduates review. May 10, 1883

27. Symonds p. 111-112

28 Symonds p. 121

29 Rhodes House Archive, File 2844 Indian lectureship. Lord Lothian to Thompson (10 June 1932); Thompson to Lothian (23 May 1933)

30 Ibid. Lothian to Thompson (17 May 1933); Thaompson to Lothian (23 May 1933)

31. V. Raghavan (ed.) Sanskrit and allied indological studies in Europe. Madras : University of Madras, 1956 p.68

32 Times Wed Jun 1, 1955

33. Oxford University Gazette 3 June 1955 p. 1003-4

34 Times 15th July 1965