by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/23/21

Dharmaśāstra (Sanskrit: धर्मशास्त्र) is a genre of Sanskrit theological texts, and refers to the treatises (śāstras) of Hinduism on dharma. There are many Dharmashastras, variously estimated to be 18 to about 100, with different and conflicting points of view.[1][note 1] Each of these texts exist in many different versions, and each is rooted in Dharmasutra texts dated to 1st millennium BCE that emerged from Kalpa (Vedanga) studies in the Vedic era.[???!!!][3][4]

The textual corpus of Dharmaśāstra were composed in poetic verses,[5] are part of the Hindu Smritis,[6] constituting divergent commentaries and treatises on duties, responsibilities and ethics to oneself, to family and as a member of society.[7][8] The texts include discussion of ashrama (stages of life), varna (social classes), purushartha (proper goals of life), personal virtues and duties such as ahimsa (non-violence) against all living beings, rules of just war, and other topics.[9][10][11]

Dharmaśāstra became influential in modern colonial India history, when they were formulated by early British colonial administrators to be the law of the land[???] for all non-Muslims (Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, Sikhs) in South Asia, after Sharia i.e. Mughal Empire's Fatawa-e-Alamgiri[12][13] set by Emperor Muhammad Aurangzeb, was already accepted as the law for Muslims in colonial India.[/b][14][15][16]

The only means of penetrating into Indian antiquity, especially as far as history is concerned, is to have a great taste for this science, to acquire a perfect knowledge of samskret, and to incur expenses to which it is impossible. Only a great prince can provide; until these three things are found united in the same subject, with the health necessary to support the study in India, nothing, or almost nothing, will be known of the ancient history of this vast Kingdom.

Let us enter the sanctuary of the Bracmanes, a sanctuary impenetrable to the eyes of the vulgar. What, after the nobility of their caste, raises them infinitely above the vulgar, is the science of religion, mathematics, and philosophy. The Bracmanes have their religion apart; they are, however, the ministers of that of the people. The four vedan or bed, are, according to them, of divine authority: they are in Arabic in the King's library; thus the Bracmanes are divided into four sects, each of which has its own law. Roukou Vedan, or, according to the Hindustani pronunciation, Recbed and the Yajourvedam, are more followed in the peninsula between the two seas. Samavedam and Latharvana or Brahmavedam in the north. The vedam contain the theology of the Bracmanes; and the ancient puranam or poems, popular theology. The Vedams, as far as I can judge from what little I have seen of them, are but a collection of various superstitious, and often diabolical, practices of the ancient Richi (penitents), or Muni (anchorites). Everything is subjugated, and the very gods are subjugated to the Intrinsic force of the sacrifices, and the Mantrams, these are sacred formulas which they use to consecrate, offer, invoke, etc. I was surprised to find this one there; om, Santih, Santih, Santih, harih. You no doubt know that the letter or syllable, ôm contains the Trinity in Unity; the rest is the literal translation of Sanctus, Sanctus, Sanctus, Dominus, Harih is a name of God which means Captor.

The Vedams, in addition to the practices of the ancient Risî and Muni, contain their sentiments on the nature of God, of the soul, of the sensible world, etc. From the two theologies, the bracmanic and the popular, we have composed the holy science or of the virtue of Harmachâstram [Dharmacastras???], which contains the practice of the different religions, of the sacred or superstitious, civil or profane rites, with the laws for the administration of Justice.[???!!!] The treatises of Harmachàstram, by different authors, have multiplied ad infinitum. I will not dwell any longer on a matter which would require a large separate work, and the knowledge of which will apparently never be more than superficial.

-- Letter From Father Pons, Missionary of the Company of Jesus, to Father Du Halde, of the same Company. At Careical, on the coast of Tanjaour; in the East Indies, November 23, 1740. From "Lettres Edifiantes Et Curieuses, Ecrites Des Missions Etrangeres", by Charles Le Gobien

History

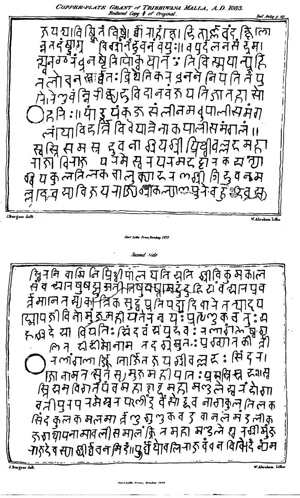

Copy of a royal land grant, recorded on copper plate, made by Chalukya King Tribhuvana Malla Deva in 1083

The Dharmashastras are based on ancient Dharmasūtra texts, which themselves emerged from the literary tradition of the Vedas (Rig, Yajur, Sāma, and Atharva) composed in 2nd millennium BCE to the early centuries of the 1st millennium BCE. These Vedic branches split into various other schools (shakhas) possibly for a variety of reasons such as geography, specialization and disputes.[17] Each Veda is further divided into two categories namely the Saṃhitā which is a collection of mantra verses and the Brahmanas which are prose texts that explain the meaning of the Samhita verses.[18] The Brāhmaṇa layer expanded and some of the newer esoteric speculative layers of text were called Aranyakas while the mystical and philosophical sections came to be called the Upanishads.[18][19] The Vedic basis of Dharma literature is found in the Brahmana layer of the Vedas.[18]

Towards the end of the vedic period, after the middle of the 1st millennium BCE, the language of the Vedic texts composed centuries earlier grew too archaic to the people of that time. This led to the formation of Vedic Supplements called the Vedangas which literally means ‘limbs of the Veda’.[18] The Vedangas were ancillary sciences that focused on understanding and interpreting the Vedas composed many centuries earlier, and included Shiksha (phonetics, syllable), Chandas (poetic metre), Vyakarana (grammar, linguistics), Nirukta (etymology, glossary), Jyotisha (timekeeping, astronomy), and Kalpa (ritual or proper procedures). The Kalpa Vedanga studies gave rise to the Dharma-sutras, which later expanded into Dharma-shastras.[18][20][21]

The Dharmasutras

The Dharmasutras were numerous, but only four texts have survived into the modern era.[22] The most important of these texts are the sutras of Apastamba, Gautama, Baudhayana, and Vasistha.[23] These extant texts cite writers and refer opinions of seventeen authorities, implying that a rich Dharmasutras tradition existed prior to when these texts were composed.[24][25]

The extant Dharmasutras are written in concise sutra format,[26] with a very terse incomplete sentence structure which are difficult to understand and leave much to the reader to interpret.[22] The Dharmasastras are derivative works on the Dharmasutras, using a shloka (four 8-syllable verse style chandas poetry, Anushtubh meter), which are relatively clearer.[22][5]

The Dharmasutras can be called the guidebooks of dharma as they contain guidelines for individual and social behavior, ethical norms, as well as personal, civil and criminal law.[22] They discuss the duties and rights of people at different stages of life like studenthood, householdership, retirement and renunciation. These stages are also called ashramas. They also discuss the rites and duties of kings, judicial matters, and personal law such as matters relating to marriage and inheritance.[23] However, Dharmasutras typically did not deal with rituals and ceremonies, a topic that was covered in the Shrautasutras and Grihyasutras texts of the Kalpa (Vedanga).[22]

Style of composition

The hymns of Ṛgveda are one of the earliest texts composed in verse. The Brāhmaṇa which belongs to the middle vedic period followed by the vedāṇga are composed in prose. The basic texts are composed in an aphoristic style known as the sutra which literally means thread on which each aphorism is strung like a pearl.[27]

The Dharmasūtras are composed in sutra style and were part of a larger compilation of texts, called the Kalpasūtras which give an aphoristic description of the rituals, ceremonies and proper procedures. The Kalpasutras contain three sections, namely the Śrautasūtras which deal with vedic ceremonies, Gṛhyasūtras which deal with rites of passage rituals and domestic matters, and Dharmasūtras which deal with proper procedures in one's life.[28] The Dharmasūtras of Āpastamba and Baudhāyana form a part of larger Kalpasutra texts, all of which has survived into the modern era.[28]

The sūtra tradition ended around the beginning of the common era and was followed by the poetic octosyllable verse style called the śloka.[29] The verse style was used to compose the Dharmaśāstras such as the Manusmriti, the Hindu epics, and the Puranas.[29]

The age of Smṛtis that ended around the second half of the first millennium CE was followed by that of commentaries around the 9th century called nibandha. This legal tradition consisted of commentaries on earlier Dharmasūtras and Smritis.[29]

Authorship and dates

About 20 Dharmasutras are known, some surviving into the modern era just as fragments of their original.[30] Four Dharmasūtras have been translated into English, and most remain in manuscripts.[30] All carry the names of their authors, but it is still difficult to determine who these real authors were.[29]

The extant Dharmasūtra texts are listed below:

1. Apastamba (450–350 BCE) this Dharmasūtra forms a part of the larger Kalpasūtra of Apastamba. It contains 1,364 sutras.[31]

2. Gautama (600–200 BCE) although this Dharmasūtra comes down as an independent treatise it may have once formed a part of the Kalpasūtra, linked to the Samaveda.[32] It is likely the oldest extant Dharma text, and originated in what is modern Maharashtra-Gujarat.[33] It contains 973 sutras.[34]

3. Baudhāyana (500–200 BCE) this Dharmasūtra like that of Apastamba also forms a part of the larger Kalpasūtra. It contains 1,236 sutras.[31]

4. Vāsiṣṭha (300–100 BCE) this Dharmasūtra forms an independent treatise and other parts of the Kalpasūtra, that is Shrauta- and Grihya-sutras are missing.[30] It contains 1,038 sutras.[31]

The Dharmasūtra of Āpastamba and Baudhayana form a part of the Kalpasūtra but it is not easy to establish whether they were historical authors of these texts or whether these texts were composed within certain institutions attributed to their names.[29] Moreover, Gautama and Vasiṣṭha are ancient sages related to specific vedic schools and therefore it is hard to say whether they were historical authors of these texts.[35] The issue of authorship is further complicated by the fact that apart from Āpastamba the other Dharmasūtras have various alterations made at later times.[35]

Excellence

Practise righteousness (dharma), not unrighteousness.

Speak the truth, not an untruth.

Look at what is distant, not what's near at hand.

Look at the highest, not at what's less than highest.

— Vasishtha Dharmasutra 30.1 [36]

There is uncertainty regarding the dates of these documents due to lack of evidence concerning these documents. Kane has posited the following dates for the texts, for example, though other scholars disagree: Gautama 600 BCE to 400 BCE, Āpastamba 450 BCE to 350 BCE, Baudhāyana 500 BCE to 200 BCE, and Vasiṣṭha 300 BCE to 100 BCE.[37] Patrick Olivelle suggests that Apastamba Dharmasutra is the oldest of the extant texts in Dharmasutra genre and one by Gautama second oldest, while Robert Lingat suggests that Gautama Dharmasutra is the oldest.[38][33]

There is confusion regarding the geographical provenance of these documents. According to Bühler and Kane, Āpastamba came from South India probably from a region corresponding to modern Andhra Pradesh.[39] Baudhāyana also came from south although evidence regarding this is weaker than that of Āpastamba.[39] Gautama likely came from western region, nearer to the northwestern region to which Pāṇini belonged, and one which corresponds to where Maratha people in modern India are found.[32] Nothing can be said about Vasiṣṭha due to lack of any evidence.[40]

Scholars have varied opinions about the chronology of these documents. Regarding the age of Āpastamba and Gautama there are opposite conclusions. According to Bühler and Lingat Āpastamba is younger than Baudhāyana. Vasiṣṭha is surely a later text.[40]

Literary structure

The structure of these Dharmasūtras primarily addresses the Brahmins both in subject matter and the audience.[41] The Brahmins are the creators and primary consumers of these texts.[41] The subject matter of Dharmasūtras is dharma. The central focus of these texts is how a Brahmin male should conduct himself during his lifetime.[41] The text of Āpastamba which is best preserved has a total of 1,364 sūtras out of which 1,206 (88 per cent) are devoted to the Brahmin, whereas only 158 (12 per cent) deals with topics of general nature.[42] The structure of the Dharmasūtras begin with the vedic initiation of a young boy followed by entry into adulthood, marriage and responsibilities of adult life that includes adoption, inheritance, death rituals and ancestral offerings.[42] According to Olivelle, the reason Dharmasutras introduced vedic initiation was to make the individual subject to Dharma precepts at school, by making him a ‘twice born’ man, because children were considered exempt from Dharma precepts in the vedic tradition.[42]

The structure of Dharmasūtra of Āpastamba begins with the duties of the student, then describes householder duties and rights such as inheritance, and ends with administration of the king.[43] This forms the early structure of the Dharma texts. However, in the Dharmasūtras of Gautama, Baudhāyana and Vasiṣṭha some sections such as inheritance and penance are reorganized, and moved from householder section to king-related section.[43] Ollivelle suggests that these changes may be because of chronological reasons where civil law increasingly became part of the king's administrative responsibilities.[43]

The meaning of Dharma

Dharma is a concept which is central not only in Hinduism but also in Jainism and Buddhism.[44] The term means a lot of things and has a wide scope of interpretation.[44] The fundamental meaning of Dharma in Dharmasūtras, states Olivelle is diverse, and includes accepted norms of behavior, procedures within a ritual, moral actions, righteousness and ethical attitudes, civil and criminal law, legal procedures and penance or punishment, and guidelines for proper and productive living.[45]

The term Dharma also includes social institutions such as marriage, inheritance, adoption, work contracts, judicial process in case of disputes, as well personal choices such as meat as food and sexual conduct.[46]

The source of Dharma: scriptures or empiricism

The source of dharma was a question that loomed in the minds of Dharma text writers, and they tried to seek "where guidelines for Dharma can be found?"[47] They sought to define and examine vedic injunctions as the source of Dharma, asserting that like the Vedas, Dharma is not of human origin.[47] This worked for rituals-related rules, but in all other matters this created numerous interpretations and different derivations.[47] This led to documents with various working definitions, such as dharma of different regions (deshadharma), of social groups (jatidharma), of different families (kuladharma).[47] The authors of Dharmasutras and Dharmashastra admit that these dharmas are not found in the Vedic texts, nor can the behavioral rules included therein be found in any of the Vedas.[47] This led to the incongruity between the search for legal codes and dharma rules in the theological versus the reality of epistemic origins of dharma rules and guidelines.[47]

The Hindu scholar Āpastamba, in a Dharmasutra named after him (~400 BCE), made an attempt to resolve this issue of incongruity. He placed the importance of the Veda scriptures second and that of samayacarika or mutually agreed and accepted customs of practice first.[48] Āpastamba thus proposed that scriptures alone cannot be source of Law (dharma), and dharma has an empirical nature.[48] Āpastamba asserted that it is difficult to find absolute sources of law, in ancient books or current people, states Patrick Olivelle with, "The Righteous (dharma) and the Unrighteous (adharma) do not go around saying, 'here we are!'; Nor do gods, Gandharvas or ancestors declare, 'This is righteous and that is unrighteous'."[48] Most laws are based on agreement between the Aryas, stated Āpastamba, on what is right and what is wrong.[48] Laws must also change with ages, stated Āpastamba, a theory that became known as Yuga dharma in Hindu traditions.[49] Āpastamba also asserted in verses 2.29.11–15, states Olivelle, that "aspects of dharma not taught in Dharmasastras can be learned from women and people of all classes".[50]

Āpastamba used a hermeneutic strategy that asserted that the Vedas once contained all knowledge including that of ideal Dharma, but parts of Vedas have been lost.[49] Human customs developed from the original complete Vedas, but given the lost text, one must use customs between good people as a source to infer what the original Vedas might have stated the Dharma to be.[49] This theory, called the ‘lost Veda’ theory, made the study of customs of good people as a source of dharma and guide to proper living, states Olivelle.[49]

Testimony during a trial

The witness must take an oath before deposing.

Single witness normally does not suffice.

As many as three witnesses are required.

False evidence must face sanctions.

— Gautama Dharmasutras 13.2–13.6 [51][52]

The sources of dharma according to Gautama Dharmasutra are three: the Vedas, the Smriti (tradition), acāra (the practice) of those who know the Veda. These three sources are also found in later Dharmashastra literature.[49] Baudhāyana Dharmasutra lists the same three, but calls the third as śiṣṭa (शिष्ट, literally polite cultured people)[note 2] or the practice of cultured people as the third source of dharma.[49] Both Baudhāyana Dharmasutra and Vāsiṣṭha Dharmasutra make the practices of śiṣṭa as a source of dharma, but both state that the geographical location of such polite cultured people does not limit the usefulness of universal precepts contained in their practices.[49] In case of conflict between different sources of dharma, Gautama Dharmasutra states that the Vedas prevail over other sources, and if two Vedic texts are in conflict then the individual has a choice to follow either.[54]

The nature of Dharmasūtras is normative, they tell what people ought to do, but they do not tell what people actually did.[55] Some scholars state that these sources are unreliable and worthless for historical purposes instead to use archaeology, epigraphy and other historical evidence to establish the actual legal codes in Indian history. Olivelle states that the dismissal of normative texts is unwise, as is believing that the Dharmasutras and Dharmashastras texts present a uniform code of conduct and there were no divergent or dissenting views.[55]

The Dharmaśāstras

Written after the Dharmasūtras, these texts use a metered verse and are much more elaborate in their scope than Dharmasutras.[56] The word Dharmaśāstras never appears in the Vedic texts, and the word śāstra itself appears for the first time in Yaska's Nirukta text.[57] Katyayana's commentary on Panini's work (~3rd century BCE), has the oldest known single mention of the word Dharmaśāstras.[57]

The extant Dharmaśāstras texts are listed below:

1. The Manusmriti (~ 2nd to 3rd century CE)[58][59] is the most studied and earliest metrical work of the Dharmaśāstra textual tradition of Hinduism.[60] The medieval era Buddhistic law of Myanmar and Thailand are also ascribed to Manu,[61][62] and the text influenced past Hindu kingdoms in Cambodia and Indonesia.[63]

2. The Yājñavalkya Smṛti (~ 4th to 5th-century CE)[58] has been called the "best composed" and "most homogeneous"[64] text of the Dharmaśāstra tradition, with its superior vocabulary and level of sophistication. It may have been more influential than Manusmriti as a legal theory text.[65][66]

3. The Nāradasmṛti (~ 5th to 6th-century CE)[58] has been called the "juridical text par excellence" and represents the only Dharmaśāstra text which deals solely with juridical matters and ignoring those of righteous conduct and penance.[67]

4. The Viṣṇusmṛti (~ 7th-century CE)[58] is one of the latest books of the Dharmaśāstra tradition in Hinduism and also the only one which does not deal directly with the means of knowing dharma, focusing instead on the bhakti tradition.[68]

In addition, numerous other Dharmaśāstras are known,[69][note 3] partially or indirectly, with very different ideas, customs and conflicting versions.[72] For example, the manuscripts of Bṛhaspatismṛti and the Kātyāyanasmṛti have not been found, but their verses have been cited in other texts, and scholars have made an effort to extract these cited verses, thus creating a modern reconstruction of these texts.[73] Scholars such as Jolly and Aiyangar have gathered some 2,400 verses of the lost Bṛhaspatismṛti text in this manner.[73] Brihaspati-smriti was likely a larger and more comprehensive text than Manusmriti,[73] yet both Brihaspati-smriti and Katyayana-smriti seem to have been predominantly devoted to judicial process and jurisprudence.[74] The writers of Dharmasastras acknowledged their mutual differences, and developed a "doctrine of consensus" reflecting regional customs and preferences.[75]

Of the four extant Dharmasastras, Manusmriti, Yajnavalkyasmriti and Naradasmriti are the most important surviving texts.[76] But, states Robert Lingat, numerous other Dharmasastras whose manuscripts are now missing, have enjoyed equal authority.[76] Between the three, the Manusmriti became famous during the colonial British India era, yet modern scholarship states that other Dharmasastras such as the Yajnavalkyasmriti appear to have played a greater role in guiding the actual Dharma.[77] Further, the Dharmasastras were open texts, and they underwent alterations and rewriting through their history.[78]

Contents of Dharmasutras and Dharmaśāstra

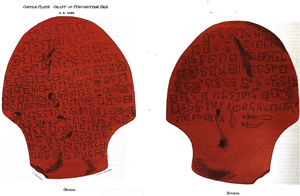

A facsimile of an inscription in Oriya script on a copper plate recording a land grant made by Rāja Purushottam Deb, king of Odisha, in the fifth year of his reign (1483). Land grants made by royal decree were protected by law, with deeds often being recorded on metal plates

All Dharma, in Hindu traditions, has its foundation in the Vedas.[19] The Dharmashastra texts enumerate four sources of Dharma – the precepts in the Vedas, the tradition, the virtuous conduct of those who know the Vedas, and approval of one's conscience (Atmasantushti, self-satisfaction).[79]

The Dharmashastra texts include conflicting claims on the sources of dharma. The theological claim therein asserts, without any elaboration, that Dharma just like the Vedas are eternal and timeless, the former is directly or indirectly related to the Vedas.[80] Yet these texts also acknowledge the role of Smriti, customs of polite learned people, and one's conscience as source of dharma.[79][80] The historical reality, states Patrick Olivelle, is very different than the theological reference to the Vedas, and the dharma taught in the Dharmaśāstra has little to do with the Vedas.[80] These were customs, norms or pronouncements of the writers of these texts that were likely derived from evolving regional ethical, ideological, cultural and legal practices.[81]

The Dharmasutra and Dharmaśāstra texts, as they have survived into the modern era, were not authored by a single author. They were viewed by the ancient and medieval era commentators, states Olivelle, to be the works of many authors.[82] Robert Lingat adds that these texts suggest that "a rich literature on dharma already existed" before these were first composed.[83] These texts were revised and interpolated through their history because the various text manuscripts discovered in India are inconsistent with each other, and within themselves, raising concerns of their authenticity.[84][85][86]

The Dharmaśāstra texts present their ideas under various categories such as Acara, Vyavahara, Prayascitta and others, but they do so inconsistently.[87] Some discuss Acara but do not discuss Vyavahara, as is the case with Parasara-Smriti for instance,[88] while some solely discuss Vyavahara.[74]

Āchara

Main article: Āchara

Āchara (आचार) literally means "good behavior, custom".[89][90] It refers to the normative behavior and practices of a community, conventions and behaviors that enable a society and various individuals therein to function.[91][92]

Vyavahāra

Main article: Vyavahāra

Vyavahāra (व्यवहार) literally means "judicial procedure, process, practice, conduct and behaviour".[93][94] The due process, honesty in testimony, considering various sides, was justified by Dharmaśāstra authors as a form of Vedic sacrifice, failure of the due process was declared to be a sin.[95][96]

The Vyavahara sections of Dharma texts included chapters on duties of a king, court system, judges and witnesses, judicial process, crimes and penance or punishment.[94] However, the discussions and procedures in different Dharmasutra and Dharmaśāstra texts diverge significantly.[94]

Some Dharmaśāstra texts such as that attributed to Brihaspati, are almost entirely Vyavahāra-related texts. These were probably composed in the common era, around or after 5th-century of 1st millennium.[74]

Prāyaśchitta

Main article: Prāyaśchitta

Prāyaśchitta (प्रायश्चित्त) literally means "atonement, expiation, penance".[97][98] Prāyaśchittas are asserted by the Dharmasutra and Dharmashastra texts as an alternative to incarceration and punishment,[98] and a means of expiating bad conduct or sin such as adultery by a married person.[99] Thus, in the Apastambha text, a willing sexual act between a male and female is subject to penance, while rape is covered by harsher judicial punishments, with a few texts such as Manusmriti suggesting public punishments in extreme cases.[98]

Those texts that discuss Prāyaśchitta, states Robert Lingat, debate the intent and thought behind the improper act, and consider penance appropriate when the "effect" had to be balanced, but "cause" was unclear.[100] The roots of this theory are found in the Brahmana layer of text in the Samaveda.[101]

Secondary works

The Dharmasutras and Dharmasastras attracted secondary works called commentaries (Bhashya) would typically interpret and explain the text of interest, accept or reject the ideas along with reasons why.[102]

Commentaries (bhasya) on Dharmasastras

Dharmasastra / Author of Commentary

Manusmriti / Bhāruci (600–1050 CE),[103] Medhātithi (820–1050 CE),[104] Govindarāja (11th-century),[105] Kullūka (1200–1500 CE),[105] Narayana (14th-century),[105] Nandana,[105] Raghavananda,[105] Ramacandra[105]

Yajnavalkya Smriti / Visvarupa (750–1000 CE), Vijanesvara (11th or 12th century, most studied), Apararka (12th-century), Sulapani (14th or 15th century), Mitramisra (17th-century)[106][107]

Narada-smriti / Kalyāṇbhaṭṭa (based on Asahaya's work)[106][107]

Visnu-smriti / Nandapaṇḍita[106]

Another category of secondary literature derived from the Dharmasutras and Dharmasastras were the digests (nibandhas, sometimes spelled nibhandas). These arose primarily because of the conflict and disagreements on a particular subject across the various Dharma texts.[108] These digests attempted to reconcile, bridge or suggest a compromise guideline to the numerous disagreements in the primary texts, however the digests in themselves disagreed with each other even on basic principles.[109] Geographically, the medieval era digest writers came from many different parts of India, such as Assam, Bengal, Bihar, Gujarat, Kashmir, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh.[110] The oldest surviving digest on Dharma texts is Krityakalpataru, from early 12th-century, by Lakshmidhara of Kannauj in north India, belonging to the Varanasi school.[111]

The digests were generally arranged by topic, referred to many different Dharmasastras for their contents. They would identify an idea or rule, add their comments, then cite contents of different Dharma texts to support or explain their view.

Digests (nibhandas) on Dharmasastras

Subject / Author of Digests

General / Lakṣmīdhara (1104–1154 CE),[111] Devaṇṇa-bhaṭṭan (1200 CE), Pratāparuda-deva (16th-century),[112] Nīlakaṇṭha (1600–1650),[113] Dalpati (16th-century), Kashinatha (1790)[114]

Inheritance / Jīmūtavāhana, Raghunandana

Adoption / Nanda-paṇḍita (16th–17th century)[115]

King's duties / Caṇḍeśvara, Ṭoḍar Mal (16th century, sponsored by the Mughal emperor Akbar)[116]

Judicial process / Caṇḍeśvara (14th century), Kamalākara-bhatta (1612), Nīlakaṇṭha (17th century),[113] Mitra-miśra (17th century)

Women jurists

A few notable historic digests on Dharmasastras were written by women.[117][118] These include Lakshmidevi's Vivadachandra and Mahadevi Dhiramati's Danavakyavali.[117] Lakshmidevi, state West and Bühler, gives a latitudinarian views and widest interpretation to Yajnavalkya Smriti, but her views were not widely adopted by male legal scholars of her time.[118] The scholarly works of Lakshmidevi were also published with the pen name Balambhatta, and are now considered classics in legal theories on inheritance and property rights, particularly for women.[119]

Dharma texts and the schools of Hindu philosophy

The Mimamsa school of Hindu philosophy developed textual hermeneutics, theories on language and interpretation of Dharma, ideas which contributed to the Dharmasutras and Dharmasastras.[120] The Vedanga fields of grammar and linguistics – Vyakarana and Nirukta – were the other significant contributors to the Dharma-text genre.[120]

Mimamsa literally means the "desire to think", states Donald Davis, and in colloquial historical context "how to think, interpret things, and the meaning of texts".[120] In the early portions of the Vedas, the focus was largely on the rituals; in the later portions, largely on philosophical speculations and the spiritual liberation (moksha) of the individual.[120][121] The Dharma-texts, over time and each in its own way, attempted to present their theories on rules and duties of individuals from the perspective of a society, using the insights of hermeneutics and on language developed by Mimamsa and Vedanga.[120][121][122] The Nyaya school of Hindu philosophy, and its insights into the theories on logic and reason, contributed to the development of and disagreements between the Dharmasastra texts, and the term Nyaya came to mean "justice".[123][124]

Influence

Main article: Hindu law

Dharmaśāstras played an influential role in modern era colonial India history, when they were used as the basis for the law of the land for all non-Muslims (Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, Sikhs).[15][16][125]

In 18th century, the earliest British of the East India Company acted as agents of the Mughal emperor. As the British colonial rule took over the political and administrative powers in India, it was faced with various state responsibilities such as legislative and judiciary functions.[126] The East India Company, and later the British Crown, sought profits for its British shareholders through trade as well as sought to maintain effective political control with minimal military engagement.[127] The administration pursued a path of least resistance, relying upon co-opted local intermediaries that were mostly Muslims and some Hindus in various princely states.[127] The British exercised power by avoiding interference and adapting to law practices as explained by the local intermediaries.[126][127][128] The colonial policy on the system of personal laws for India, for example, was expressed by Governor-General Hastings in 1772 as follows,

That in all suits regarding inheritance, marriage, caste and other religious usages or institutions, the law of the Koran with respect to Mahometans, and those of the Shaster [Dharmaśāstra] with respect to Gentoos shall be invariably be adhered to.

— Warren Hastings, August 15, 1772[125]

For Muslims of India, the Sharia or the religious law for Muslims was readily available in al-Hidaya and Fatawa-i Alamgiri written under the sponsorship of Aurangzeb. For Hindus and other non-Muslims such as Buddhists, Sikhs, Jains, Parsis and Tribal people, this information was unavailable.[126] The British colonial officials extracted from the Dharmaśāstra, the legal code to apply on non-Muslims for the purposes of colonial administration.[129][130]

The Dharmashastra-derived laws for non-Muslim Indians were dissolved after India gained independence, but Indian Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act of 1937 continued to be the personal and family law for Indian Muslims.[131] For non-Muslims, a non-religious uniform civil code was passed by Indian parliament in the 1950s, and amended by its elected governments thereafter, which has since then applied to all non-Muslim Indians.[131]

Major English translations

For beginners

• Olivelle, Patrick. 1999. Dharmasūtras: The Law Codes of Āpastamba, Gautama, Baudhāyana, and Vāsiṣṭha. New York: Oxford UP.

• Olivelle, Patrick. 2004. The Law Code of Manu. New York: Oxford UP.

Other major translations

• Kane, P.V. (ed. and trans.) 1933. Kātyāyanasmṛti on Vyavahāra (Law and Procedure). Poona: Oriental Book Agency.

• Lariviere, Richard W. 2003. The Nāradasmṛti. 2nd rev. ed. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

• Rocher, Ludo. 1956. Vyavahāracintāmani: a digest on Hindu legal procedure. Gent.

Early translations with full-text online

• Jha, Ganganath (trans.), Manusmṛti with the Manubhāṣyya of Medhātithi, including additional notes, 1920.

• Bühler, Georg (trans.), The Laws of Manu, SBE Vol. 25, 1886.

• Bühler, Georg (trans.), The Sacred Laws of the Āryas, SBE Vol. 2, 1879 [Part 1: Āpastamba and Gautama]

• Bühler, Georg (trans.), The Sacred Laws of the Āryas, SBE Vol. 14, 1882 [Part 2: Vāsiṣṭha and Baudhāyana]

• Jolly, Julius (trans.), The Institutes of Viṣṇu, SBE Vol. 7, 1880.

• Jolly, Julius (trans.), The Minor Law-Books, SBE Vol. 33. Oxford, 1889. [contains both Bṛhaspatismṛti and Nāradasmṛti]

See also

• Dhammasattha

• Tirukkural

Notes

1. Pandurang Vaman Kane mentions over 100 different Dharmasastra texts which were known by the Middle Ages in India, but most of these are lost to history and their existence is inferred from quotes and citations in bhasya and digests that have survived.[2]

2. Baudhayana, in verses 1.1.5–6, provides a complete definition of śiṣṭa as "Now, śiṣṭa are those who are free from envy and pride, who possess just a jarful of grain, who are without greed, and who are free from hypocrisy, arrogance, greed, folly and anger."[53]

3. Numerous Dharmasastras are known, but most are lost to history and only known from them being mentioned or quoted in other surviving texts. For example, Dharmasastras by Atri, Harita, Ushanas, Angiras, Yama, Apastamba, Samvartha, Katyayana, Brihaspati, Parasara, Vyasa, Sankha, Likhita, Daksha, Gautama, Satatapa, Vasistha, Prachetas, Budha, Devala, Sumantu, Jamadgni, Visvamitra, Prajapati, Paithinasi, Pitamaha, Jabala, Chhagaleya, Chyavana, Marichi, Kasyapa, Gobhila, Risyasrimaga and others.[70][71]

References

1. John Bowker (2012), The Message and the Book: Sacred Texts of the World's Religions, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0300179293, pages 179–180

2. Kane, P.V. History of the Dharmaśāstras Vol. 1 p. 304

3. James Lochtefeld (2002), "Dharma Shastras" in The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A-M, Rosen Publishing, ISBN 0-8239-2287-1, pages 191–192

4. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxiii–xxv.

5. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 73.

6. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 173, 175–176, 183.

7. Patrick Olivelle, Manu's Code of Law: A Critical Edition and Translation of the Mānava-Dharmaśāstra (New York: Oxford UP, 2005), 64.

8. Ludo Rocher, "Hindu Law and Religion: Where to draw the line?" in Malik Ram Felicitation Volume, ed. S.A.J. Zaidi. (New Delhi, 1972), pp.167–194 and Richard W. Lariviere, "Law and Religion in India" in Law, Morality, and Religion: Global Perspectives, ed. Alan Watson (Berkeley: University of California Press), pp.75–94.

9. Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, pages 31–32, 81–82, 154–166, 208–214, 353–354, 356–382

10. Donald Davis (2010), The Spirit of Hindu Law, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521877046, page 13-16, 166–179

11. Kedar Nath Tiwari (1998). Classical Indian Ethical Thought. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 88–95. ISBN 978-81-208-1607-7.

12. Jackson, Roy (2010). Mawlana Mawdudi and Political Islam: Authority and the Islamic State. Routledge. ISBN 9781136950360.

13. Chapra, Muhammad Umer (2014). Morality and Justice in Islamic Economics and Finance. Edward Elgar Publishing. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781783475728.

14. Rocher, Ludo (July–September 1972). "Indian Response to Anglo-Hindu Law". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 92 (3): 419–424. doi:10.2307/600567. JSTOR 600567.

15. Derrett, J. Duncan M. (November 1961). "The Administration of Hindu Law by the British". Comparative Studies in Society and History. Cambridge University Press. 4 (1): 10–52. doi:10.1017/S0010417500001213. JSTOR 177940.

16. Werner Menski (2003), Hindu Law: Beyond tradition and modernity, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-569921-0, Chapter 1

17. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxii.

18. (Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxiii)

19. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 7–8.

20. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 12.

21. Rajendra Prasad (2009). A Historical-developmental Study of Classical Indian Philosophy of Morals. Concept. p. 147. ISBN 978-81-8069-595-7.

22. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxiv–xxv.

23. (Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxiii–xxv)

24. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 19–22, Quote: The dharma-sutra of Apastamba suggests that a rich literature on dharma already existed. He cites ten authors by name. (...).

25. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 178, see note 29 for a list of 17 cited ancient scholars in different Dharmasutras.

26. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 178.

27. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxiv.

28. (Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxiv)

29. (Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxv)

30. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 18.

31. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 185.

32. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 19.

33. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 19–20.

34. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 46.

35. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxvi.

36. Patrick Olivelle 1999, p. 325.

37. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxxi.

38. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 178 with note 28.

39. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxvii.

40. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxviii.

41. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxxiv.

42. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxxv.

43. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxxvi.

44. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxxvii.

45. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxxviii–xxxix.

46. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxxviii–xxxix, 27–28.

47. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xxxix.

48. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xl.

49. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xli.

50. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 180.

51. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 69.

52. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. 100–101.

53. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 181.

54. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. xlii.

55. Patrick Olivelle 1999, pp. x1ii.

56. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 73–77.

57. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 169–170.

58. Timothy Lubin, Donald R. Davis Jr & Jayanth K. Krishnan 2010, p. 57.

59. Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, pages 24–25

60. See Flood 1996: 56 and Olivelle 2005.

61. Steven Collins (1993), The discourse of what is primary, Journal of Indian philosophy, Volume 21, pages 301–393

62. Patrick Olivelle 2005, pp. 3–4.

63. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 77.

64. Lingat 1973: 98

65. Timothy Lubin, Donald R. Davis Jr & Jayanth K. Krishnan 2010, pp. 59–72.

66. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 98.

67. Lariviere 1989: ix

68. Olivelle 2007: 149–150.

69. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 277.

70. Mandagadde Rama Jois 1984, pp. 22.

71. Benoy Kumar Sarkar (1985). The Positive Background of Hindu Sociology. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 192–194. ISBN 978-81-208-2664-9.

72. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 195–198.

73. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 104.

74. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 188.

75. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 14, 109–110, 180–189.

76. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 97.

77. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 98, 103–106.

78. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 130–131.

79. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 6.

80. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 173–174.

81. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 175–178, 184–185.

82. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 176–177.

83. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 22.

84. Patrick Olivelle (2005), Manu's Code of Law, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195171464, pages 353–354, 356–382

85. G Srikantan (2014), Entanglements in Legal History (Editor: Thomas Duve), Max Planck Institute: Germany, ISBN 978-3944773001, page 123

86. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 129–131.

87. P.V. Kane, History of Dharmaśāstra: (ancient and mediaeval, religious and civil law). (Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1962 – 1975).

88. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 158–159.

89. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 103, 159.

90. Patrick Olivelle 2006, p. 172.

91. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 172–173.

92. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 14–16.

93. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 285.

94. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 186–188.

95. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 149–150.

96. On this topic, see Olivelle, Patrick, Language, Tests, and Society: Explorations in Ancient Indian Culture and Religion. p. 174

97. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 98–99.

98. Patrick Olivelle 2006, pp. 195–198 with footnotes.

99. Kane, P.V. History of the Dharmaśāstras Vol. 4 p. 38, 58

100. Robert Lingat 1973, pp. 54–56.

101. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 55.

102. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 107.

103. J Duncan J Derrett (1977), Essays in Classical and Modern Hindu Law, Brill Academic, ISBN 978-9004048089, pages 10–17, 36–37 with footnote 75a

104. Kane, P. V., History of Dharmaśāstra, (Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1975), Volume I, Part II, 583.

105. Patrick Olivelle 2005, pp. 367–369.

106. Ludo Rocher (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

107. Sures Chandra Banerji (1999). A Brief History of Dharmaśāstra. Abhinav Publications. pp. 72–75. ISBN 978-81-7017-370-0.

108. David C. Buxbaum (2013). Family Law and Customary Law in Asia: A Contemporary Legal Perspective. Springer. pp. 202–205 with footnote 3. ISBN 978-94-017-6216-8.

109. Sures Chandra Banerji (1999). A Brief History of Dharmaśāstra. Abhinav Publications. pp. 5–6, 307. ISBN 978-81-7017-370-0.

110. Sures Chandra Banerji (1999). A Brief History of Dharmaśāstra. Abhinav Publications. pp. 38–72. ISBN 978-81-7017-370-0.

111. Maria Heim (2004). Theories of the Gift in South Asia: Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain Reflections on Dāna. Routledge. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-415-97030-3.

112. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 116.

113. Sures Chandra Banerji (1999). A Brief History of Dharmaśāstra. Abhinav Publications. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-81-7017-370-0.

114. Sures Chandra Banerji (1999). A Brief History of Dharmaśāstra. Abhinav Publications. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-81-7017-370-0.

115. Robert Lingat 1973, p. 117.

116. Sures Chandra Banerji (1999). A Brief History of Dharmaśāstra. Abhinav Publications. p. 71. ISBN 978-81-7017-370-0.

117. Mandagadde Rama Jois (1984). Legal and Constitutional History of India: Ancient legal, judicial, and constitutional system. Universal Law Publishing. p. 50. ISBN 978-81-7534-206-4.

118. Sir Raymond West; Georg Bühler (1878). A Digest of the Hindu Law of Inheritance and Partition: From the Replies of the Sâstris in the Several Courts of the Bombay Presidency, with Introductions, Notes, and an Appendix. Education Society's Press. pp. 6–7, 490–491.

119. Maurice Winternitz (1963). History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 602 with footnote 2. ISBN 978-81-208-0056-4.

120. Donald R. Davis, Jr 2010, pp. 47–49.

121. Francis Xavier Clooney (1990). Thinking Ritually: Rediscovering the Pūrva Mīmāṃsā of Jaimini. De Nobili, Vienna. pp. 25–28. ISBN 978-3-900271-21-3.

122. Kisori Lal Sarkar, The Mimansa Rules of Interpretation as applied to Hindu Law. Tagore Law Lectures of 1905 (Calcutta: Thacker, Spink, 1909).

123. Ludo Rocher 2008, p. 112.

124. Mandagadde Rama Jois 1984, pp. 3, 469–481.

125. Rocher, Ludo (1972). "Indian Response to Anglo-Hindu Law". Journal of the American Oriental Society. JSTOR. 92 (3): 419–424. doi:10.2307/600567. JSTOR 600567.

126. Timothy Lubin et al (2010), Hinduism and Law: An Introduction (Editors: Lubin and Davis), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521716260, Chapter 1

127. Washbrook, D. A. (1981). "Law, State and Agrarian Society in Colonial India". Modern Asian Studies. 15 (3): 649–721. doi:10.1017/s0026749x00008714. JSTOR 312295.

128. Kugle, Scott Alan (May 2001). "Framed, Blamed and Renamed: The Recasting of Islamic Jurisprudence in Colonial South Asia". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 35 (2): 257–313. doi:10.1017/s0026749x01002013. JSTOR 313119.

129. Ludo Rocher, "Hindu Law and Religion: Where to draw the line?" in Malik Ram Felicitation Volume. ed. S.A.J. Zaidi (New Delhi, 1972), 190–1.

130. J.D.M. Derrett, Religion, Law, and the State in India (London: Faber, 1968), 96; For a related distinction between religious and secular law in Dharmaśāstra, see Lubin, Timothy (2007). "Punishment and Expiation: Overlapping Domains in Brahmanical Law". Indologica Taurinensia. 33: 93–122. SSRN 1084716.

131. Gerald James Larson (2001). Religion and Personal Law in Secular India: A Call to Judgment. Indiana University Press. pp. 50–56, 112–114. ISBN 0-253-21480-7.

Bibliography

• Donald R. Davis, Jr (2010). The Spirit of Hindu Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-48531-9.

• Mandagadde Rama Jois (1984). Legal and Constitutional History of India: Ancient legal, judicial, and constitutional system. Universal Law Publishing. ISBN 978-81-7534-206-4.

• Kane, P.V. (1973). History of DharmaŚãstra. Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental research Institute.

• Translation by Richard W. Lariviere (1989). The Nāradasmr̥ti. University of Philadelphia.

• Flood, Gavin (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43878-0.

• Timothy Lubin; Donald R. Davis Jr; Jayanth K. Krishnan (2010). Hinduism and Law: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-49358-1.

• Robert Lingat (1973). The Classical Law of India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01898-3.

• Patrick Olivelle (1999). Dharmasutras: The Law Codes of Ancient India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283882-7.

• Patrick Olivelle (2005). Manu's Code of Law. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517146-4.

• Patrick Olivelle (2006). Between the Empires: Society in India 300 BCE to 400 CE. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-977507-1.

• Ludo Rocher (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

External links

• Various Dharma Shastras Vol 1, MN Dutt (Translator), Hathi Trust

• Various Dharma Shastras Vol 2, MN Dutt (Translator), Hathi Trust

• The Cooperative Annotated Bibliography of Hindu Law and Dharmaśāstra

• Alois Payer's Dharmaśāstra Site (in German, with copious extracts in English)

• "Maharishi University of Management – Vedic Literature Collection" A Sanskrit reference to the texts of all 18 Smritis.

• History of Dharmashastra, PV Kane