by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/26/21

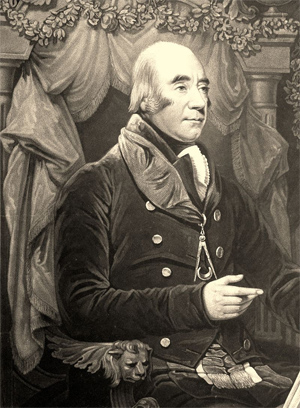

The Most Honourable The Marquess Wellesley

KG PC PC (Ire)

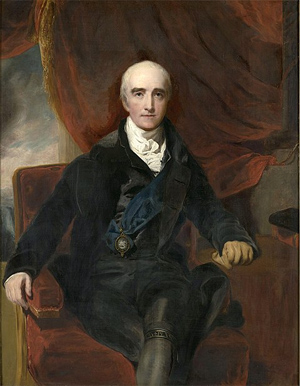

Portrait from the studio of Thomas Lawrence

Lord Lieutenant of Ireland

In office: 8 December 1821 – 27 February 1828

Monarch: George IV

Prime Minister: The Earl of Liverpool; George Canning; The Viscount Goderich

Preceded by: The Earl Talbot

Succeeded by: The Marquess of Anglesey

In office: 12 September 1833 – November 1834

Monarch: William IV

Prime Minister: The Earl Grey

Preceded by: The Marquess of Anglesey

Succeeded by: The Earl of Haddington

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

In office: 6 December 1809 – 4 March 1812

Monarch: George III

Prime Minister: Hon. Spencer Perceval

Preceded by: The Earl Bathurst

Succeeded by: Viscount Castlereagh

Governor-General of the Presidency of Fort William

In office: 18 May 1796 – 30 July 1805

Monarch: George III

Prime Minister: William Pitt the Younger; Henry Addington

Preceded by: Sir Alured Clarke (provisional)

Succeeded by: The Marquess Cornwallis

Personal details

Born: 20 June 1760, Dangan Castle, County Meath

Died: 26 September 1842 (aged 82), Knightsbridge, London

Resting place: Eton College Chapel

Nationality: Irish

Political party: Tory

Spouse(s): Hyacinthe-Gabrielle Roland (m. 1794; died 1816); Marianne (Caton) Patterson (m. 1825)

Father: Garret Wesley

Alma mater: Christ Church, Oxford

Richard Colley Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, KG, KP, PC, PC (Ire) (20 June 1760 – 26 September 1842) was an Anglo-Irish politician and colonial administrator. He was styled as Viscount Wellesley until 1781, when he succeeded his father as 2nd Earl of Mornington. In 1799, he was granted the Irish peerage title of Marquess Wellesley. He first made his name as Governor-General of India between 1798 and 1805, and he later served as Foreign Secretary in the British Cabinet and as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. He was the fifth Governor-General of India (1798-1805). In 1799, while portraying his enemy as a cruel tyrant needing to be put down, he invaded Mysore and defeated Tipu, the Sultan of Mysore, in a major battle.

He was the eldest son of The 1st Earl of Mornington, an Irish peer, and Anne, the eldest daughter of The 1st Viscount Dungannon. His younger brother, Arthur, was Field Marshal The 1st Duke of Wellington.

Education and early career

Wellesley was born in 1760 in Dangan Castle in County Meath, Ireland, where his family was part of the Ascendancy, the old Anglo-Irish aristocracy. He was educated at the Royal School, Armagh, Harrow School and Eton College, where he distinguished himself as a classical scholar, and at Christ Church, Oxford. He is one of the few men known to have attended both Harrow and Eton.

In 1780, he entered the Irish House of Commons as the member for Trim until the following year when, at his father's death, he became 2nd Earl of Mornington, taking his seat in the Irish House of Lords. He was elected Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Ireland in 1782, a post he held for the following year.[1] Due to the extravagance of his father and grandfather, he found himself so indebted that he was ultimately forced to sell all the Irish estates. However, in 1781, he was appointed to the coveted position of Custos Rotulorum of Meath.[2]

In 1784, he joined also the British House of Commons as member for the rotten borough of Bere Alston in Devon. Soon afterwards he was appointed a Lord of the Treasury by William Pitt the Younger.

In 1793, he became a member of the Board of Control over Indian affairs; and, although he was best known for his speeches in defence of Pitt's foreign policy, he was gaining the acquaintance with Oriental affairs which made his rule over India so effective from the moment when, in 1797, he accepted the office of Governor-General of India.

Work in India

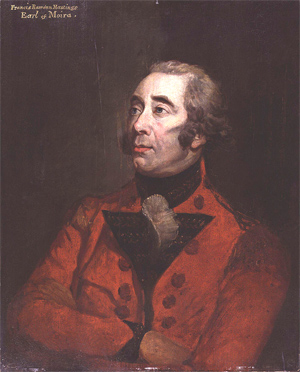

Wellesley in officer's uniform with star and sash of the Order of St Patrick. Portrait by Robert Home

Arms of Richard Wellesley, 1st Marquess Wellesley, KG, PC, with inescutcheon of pretence for Roland

Mornington seems to have caught Pitt's large political spirit in the period 1798 to 1805. That both had consciously formed the design of expanding their influence in the Indian subcontinent to compensate for the loss of the American colonies is not proved; but the rivalry with France, which in Europe placed Britain at the head of coalition after coalition against the French, made Mornington aware of the necessity of ensuring French power did not reign supreme in India.[3] On the voyage outwards, he formed the design of curbing French influence in the Deccan. Soon after his arrival, in April 1798, he learned that an alliance was being negotiated between Tipu Sultan and France. Mornington resolved to anticipate the action of the Sultan, and ordered preparations for war. The first step was to order the disbandment of the French troops entertained by the Nizam of Hyderabad.[4]

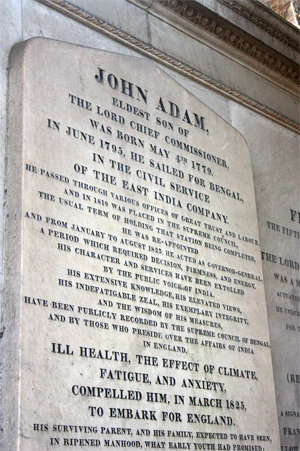

The capture of Mysore followed in February 1799, and the campaign was brought to a swift conclusion by the capture of Seringapatam on 4 May 1799 and the death of Tipu Sultan, who was killed in action. In 1803, the restoration of the Peshwa proved the prelude to the Mahratha war against Sindhia and the raja of Berar, in which his brother Arthur took a leading role. The result of these wars and of the treaties which followed them was that French influence in India was reduced to Pondicherry, and that Britain acquired increased influence in the heartlands of central India. He proved to be a skilled administrator, and picked two of his talented brothers for his staff: Arthur was his military adviser, and Henry was his personal secretary. He founded Fort William College, a training centre intended for those who would be involved in governing India. In connection with this college, he established the governor-general's office, to which civilians who had shown talent at the college were transferred, in order that they might learn something of the highest statesmanship in the immediate service of their chief. He endeavoured to remove some of the restrictions on the trade between Europe and Asia.[5] He took the time to publish an appreciation of British composer Harriet Wainwright's opera Comala in the Calcutta Post on 27 April 1804.

Both the commercial policy of Wellesley and his educational projects brought him into hostility with the court of directors, and he more than once tendered his resignation, which, however, public necessities led him to postpone till the autumn of 1805. He reached England just in time to see Pitt before his death. He had been created a Peer of Great Britain in 1797 as Baron Wellesley, and in 1799 became Marquess Wellesley in the Peerage of Ireland.[note 1][6] He formed an enormous collection of over 2,500 painted miniatures in the Company style of Indian natural history. A motion by James Paull (MP) to impeach Wellesley due to his expulsion of British traders from Oudh was defeated in the House of Commons by 182 votes to 31 in 1808.[7] Mornington also disapproved of liaisons between Company officials and soldiers and locals, seeing them as improper.[8]

Napoleonic Wars

On the fall of the coalition ministry in 1807 Wellesley was invited by George III to join the Duke of Portland's cabinet, but he declined, pending the discussion in parliament of certain charges brought against him in respect of his Indian administration. Resolutions condemning him for the abuse of power were moved in both the Lords and Commons, but defeated by large majorities.

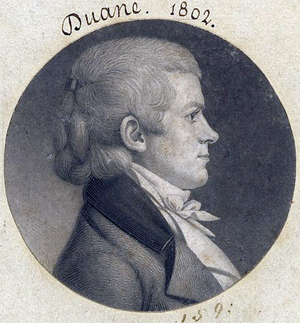

In 1809, Wellesley was appointed ambassador to Spain. He landed at Cádiz just after the Battle of Talavera, and tried unsuccessfully to bring the Spanish government into effective co-operation with his brother, who, through the failure of his allies, had been forced to retreat into Portugal. A few months later, after the duel between George Canning and Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, and the resignation of both, Wellesley accepted the post of Foreign Secretary in Spencer Perceval's cabinet. Unlike his brother Arthur, he was an eloquent speaker, but was subject to inexplicable "black-outs" when he was apparently unaware of his surroundings.

He held this office until February 1812, when he retired, partly from dissatisfaction at the inadequate support given to Wellington by the ministry, but also because he had become convinced that the question of Catholic emancipation could no longer be kept in the background. From early life Wellesley had, like his brother Arthur, been an advocate of Catholic emancipation, and with the claim of the Irish Catholics to justice he henceforward identified himself. On Perceval's assassination he, along with Canning, refused to join Lord Liverpool's administration, and he remained out of office till 1821, criticising with severity the proceedings of the Congress of Vienna and the European settlement of 1814, which, while it reduced France to its ancient limits, left to the other great powers the territory that they had acquired by the Partitions of Poland and the destruction of the Republic of Venice. He was one of the peers who signed the protest against the enactment of the Corn Laws in 1815. His reputation never fully recovered from a fiasco in 1812 when he was expected to make a crucial speech denouncing the new Government, but suffered one of his notorious "black-outs" and sat motionless in his place.

Family life

Hyacinthe-Gabrielle Roland, as painted by Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun in 1791.

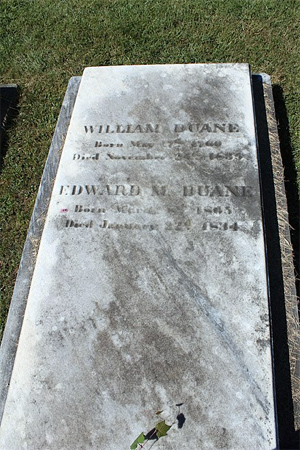

Wellesley lived together for many years with Hyacinthe-Gabrielle Roland, an actress at the Palais Royal. She had three sons and two daughters by Wellesley before he married her on 29 November 1794. He moved her to London, where Hyacinthe was generally miserable, as she never learned English and she was scorned by high society: Lady Caroline Lamb was warned by her mother-in-law, Elizabeth Milbanke, a noted judge of what was socially acceptable, that no respectable woman could afford to be seen in Hyacinthe's company.

Their children were:

• Richard Wellesley (1787–1831), a member of parliament

• Anne Wellesley (1788–1875), who married firstly Sir William Abdy, 7th Baronet, and secondly Lieutenant-Colonel Lord Charles Bentinck

• Hyacinthe Mary Wellesley (1789–1849), who married Edward Littleton, 1st Baron Hatherton

• Gerald Wellesley (1792–1833), who served as the East India Company's resident at Indore.[9]

• The Rev. Henry Wellesley (1794–1866), Principal of New Inn Hall, Oxford.[10]

Through his eldest daughter Lady Charles Bentinck, Wellesley is a great-great-great grandfather to Queen Elizabeth II.

Wellesley also had at least two other illegitimate sons by his teenage mistress, Elizabeth Johnston, including Edward (later his father's secretary), born in Middlesex (1796-1877). Wellesley's children were seen by Richard's other relatives, including his brother Arthur, as greedy, unattractive and cunning, and as exercising an unhealthy influence over their father; in the family circle they were nicknamed "The Parasites".[11]

Following his first wife's death in 1816, he married, on 29 October 1825, the widowed Marianne (Caton) Patterson (died 1853), whose mother Mary was the daughter of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, the last surviving signatory of the United States Declaration of Independence; her former sister-in-law was Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte. Wellington, who was very fond of Marianne (rumour had it that they were lovers) and was then on rather bad terms with his brother, pleaded with her not to marry him, warning her in particular that "The Parasites", (Richard's children by Hyacinthe) would see her as an enemy.[12] The Duke's concern seems to have been misplaced; they had no children, but the marriage was a relatively happy one - "much of the calm and sunshine of his old age can be attributed to Marianne".[13]

Ireland and later life

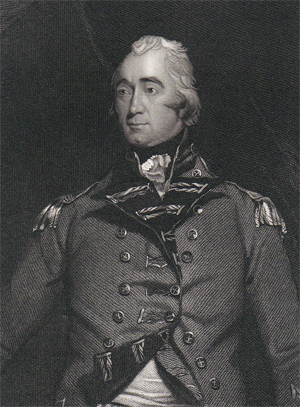

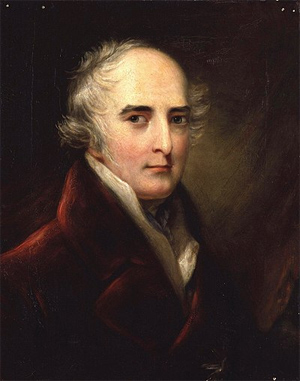

Lord Wellesley in Garter Robes, with the badge of the Grand Master of the Order of St Patrick around his neck and carrying the white staff of office as Lord Steward, presumably dressed for the coronation of King William IV on 8 September 1831. Westminster Abbey in background. Portrait by Sir Martin Archer Shee and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1833

In 1821, he was appointed Lord Lieutenant of Ireland. Catholic emancipation had now become an open question in the cabinet, and Wellesley's acceptance of the viceroyalty was believed in Ireland to herald the immediate settlement of the Catholic claims but they would remain unfulfilled. Some efforts were made to placate Catholic opinion, notably the dismissal of the long-serving Attorney-General for Ireland, William Saurin, whose anti-Catholic views had made him bitterly unpopular. Lord Liverpool died without having grappled with the problem. His successor Canning died only a few months after taking up office as Prime Minister, to be succeeded briefly by Lord Goderich.

On the assumption of office by Wellington, his brother resigned the lord-lieutenancy. He is said to have been deeply hurt by his brother's failure to find a Cabinet position for him (Arthur made the usual excuse that one cannot give a Cabinet seat to everyone who wants one).[14] He had, however, the satisfaction of seeing the Catholic claims settled in the next year by the very statesmen who had declared against them. In 1833, he resumed the office of Lord Lieutenant under Earl Grey, but the ministry soon fell, and, with one short exception, Wellesley did not take any further part in official life.

Death

On his death, he had no successor in the marquessate, but the earldom of Mornington and minor honours devolved on his brother William, Lord Maryborough, on the failure of whose issue in 1863 they fell to the 2nd Duke of Wellington.

He and Arthur, after a long estrangement, had been once more on friendly terms for some years: Arthur wept at the funeral, and said that he knew of no honour greater than being Lord Wellesley's brother.[15]

Wellesley was buried in Eton College Chapel, at his old school.[16]

Legacy

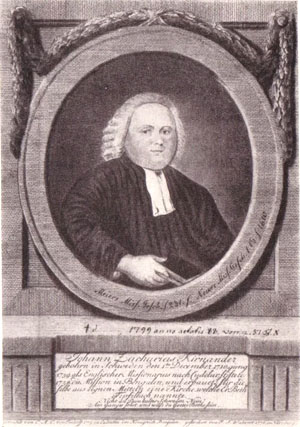

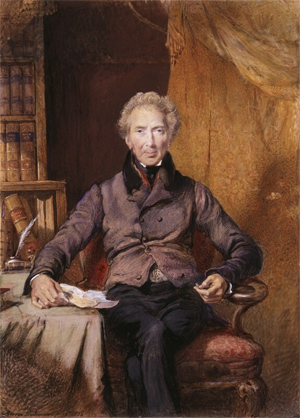

The Marquess Wellesley by John Philip Davis ("Pope" Davis).

The Township of Wellesley, in Ontario, Canada, was named in Richard Wellesley's honour, despite the many references (e.g.: Waterloo, Wellington County) to his brother, Arthur Wellesley in the surrounding area, as was Wellesley Island, located in the St. Lawrence river at Alexandria Bay. Wellesley Island also serves as the last point exiting the United States before crossing to Hill Island, in Canada.

Province Wellesley, in the state of Penang, Malaysia, was named after Richard Wellesley. It was originally part of the state of Kedah. It was ceded to the British East India Company by the Sultan of Kedah in 1798, and has been part of the settlement and state of Penang ever since. It was renamed Seberang Perai ("across the Perai" in the Malay language) not long after independence within Malaya.[17]

The Wellesley Islands off the north coast of Queensland, Australia, were named by Matthew Flinders in honour of Richard Wellesley, as was the largest island in the group, Mornington Island. Flinders is believed to have done this during his imprisonment by the French on Mauritius Island as Wellesley had tried to secure his release.[18][19][20]

Mornington Peninsula, south of Melbourne, was named after him.

As of the summer of 2007, a portrait of Marquess Wellesley hangs in the Throne Room at Buckingham Palace.

Notes

1. Having hoped to receive the Order of the Garter, Wellesley was much disappointed by an Irish peerage, which he contemptuously referred to as a "double-gilt potato."

References

1. Waite, Arthur Edward (2007). A New Encyclopedia of Freemasonry. vol. I. Cosimo, Inc. p. 400. ISBN 978-1-60206-641-0.

2. "WELLESLEY, Richard Colley, 2nd Earl of Mornington [I] (1760-1842), of Dangan Castle, co. Meath". History of Parliament. Retrieved 18 June 2014.

3. See, e.g., William McCullagh Torrens, The Marquess Wellesley: Architect of Empire(London: Chatto and Windus, 1880); P.E. Roberts, India Under Wellesley (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1929); M.S. Renick, Lord Wellesley and the Indian States (Agra: Arvind Vivek Prakashan, 1987).

4. "Hyderabad Treaty (Appendix F)," The Despatches, Minutes & Correspondence of the Marquess Wellesley During His Administration in India, ed. Robert Montgomery Martin, 5 vols (London: 1836–37), 1:672–675; Roberts, India Under Wellesley, chap. 4, “The Subsidiary Alliance System.”

5. C.H. Phillips, The East India Company, 1784–1834, 2nd. ed., (Manchester: Manchester UP, 1961), 107–108; "Notice of the Board of Trade, 5 October 1798 (Appendix M)," Wellesley Despatches, 2:736–738.

6. Mornington to Pitt, April 1800, The Wellesley Papers: The Life and Correspondence of Richard Colley Wellesley, 2 vols (London: Herbert Jenkins, 1914), 121.

7. "10 MARCH 1806. BRITISH "INVADERS SEEKING TO ESTABLISH A DOMINION AND TO ACQUIRE AN EMPIRE" IN INDIA". Dukes of Buckingham and Chandos. 3 April 2015. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

8. Dalrymple, William (2004). White Mughals: love and betrayal in eighteenth-century India. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-200412-8.

9. Margaret Makepeace. "British Library Untold Lives blog - Gerald Wellesley's secret family". Retrieved 25 April 2017.

10. Bayly, C. A. "Wellesley [formerly Wesley], Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29008.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

11. Joanne Major, Sarah Murden (30 November 2016). A Right Royal Scandal: Two Marriages That Changed History. ISBN 9781473863422. Retrieved 25 April 2017.

12. (Elizabeth Longford 1972, pp. 113–4)

13. Butler, Iris (1973). The Eldest Brother - the Marquess Wellesley 1760-1842. London: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 561.

14. (Elizabeth Longford 1972, p. 153)

15. (Elizabeth Longford 1972, p. 394)

16. http://www.geni.com

17. "P 01. A brief history of Prai". butterworthguide.com.my. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

18. "{{{2}}} (entry {{{1}}})". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

19. "Mornington Island – island in the Shire of Mornington (entry 22847)". Queensland Place Names. Queensland Government. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

20. "Three Letters from Matthew Flinders - No 13 March 1974". State Library of Victoria. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 8 November2020.

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wellesley, Richard Colley Wesley, Marquess". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bibliography

• Webb, Alfred (1878). A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & son. Unknown parameter |subpage= ignored (help); Missing or empty |title= (help)

• http://holisticthought.com/india-under- ... wellesley/

• Elizabeth Longford (November 1972). Wellington: Pillar of state. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-00250-5.

• Butler, Iris. The Eldest Brother. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1973.

• Ingram, Edward, ed. Two Views of British India: The Private Correspondence of Mr. Dundas and Lord Wellesley, 1798–1801. Bath: Adams and Dart, 1970.

• Harrington, Jack (2010), Sir John Malcolm and the Creation of British India, New York: Palgrave Macmillan., ISBN 978-0-230-10885-1

• Martin, Robert Montgomery, ed. The Despatches, Minutes & Correspondence of the Marquess Wellesley During His Administration in India. 5 vols. London: 1836–37.

• Pearce, Robert Rouiere. Memoirs and Correspondence of the Most Noble Richard Marquess Wellesley. 3 vols. London: 1846.

• Renick, M. S. Lord Wellesley and the Indian States. Agra: Arvind Vivek Prakashan, 1987.

• Roberts, P. E. India Under Wellesley. London: George Bell & Sons, 1929.

• The Wellesley Papers: The Life and Correspondence of Richard Colley Wellesley. 2 vols. London: Herbert Jenkins, 1914.

• Torrens, William McCullagh. The Marquess Wellesley: Architect of Empire. London: Chatto and Windus, 1880.