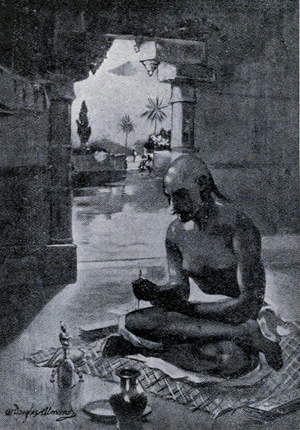

Adi Shankara

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/23/21

A biography of Sri Sankara on modern lines is an impossible for want of exact data from contemporary writings. We have therefore to depend on the type of Sanskrit works called Sankaravijayas, the traditional lives of the Acharya, to know whatever is now possible to gather about this saintly philosopher…As these Vijayas have a mythological bias, they have their obvious defect in respect of chronology and recording of facts and events…

We are presenting this translation not because we consider it a proper biography in the modern sense, but because there is nothing better to offer on the life and achievements of Sri Sankara. Sri Sankaracharya is undoubtedly the most widely known of India’s saintly philosophers, both within the country and outside, and there is a constant enquiry for an account of his life.

The trouble does not actually lie with these scholars or the accounts they have given of Sankara’s life. It lies in the fact that there is absolute dearth of reliable materials to produce a biography of the modern type on Sankara, and the scholarly writer, if he is to produce a book of some respectable size, has no other alternative but to fill it with discussions of the various versions of the dates and of the incidents of Sankara’s life that have come down to us through that series of literature known as Sankaravijayas, which vary very widely from one another in regard to most of these details….

In a situation like this, a modern writer on Sankara’s life can consider himself to have discharged his duty well if he produces a volume of respectable size filled with condemnation of the old Sankara-vijayas — which, by the way, have given him the few facts he has got to write upon—for their ‘fancifulness, unreliability, absence of chronological sense’ and a host of other obvious shortcomings, and indulge in learned discussions about the date and the evidence in favour of or against the disputed facts, and finally fill up the gap still left with expositions of Sankara’s philosophy. In contrast to these are the traditional biographical writings on Sankara called Sankara-vijayas. All of them without an exception mix the natural with the supernatural; bring into the picture the deliberations held by super-human beings in the heavens; bring gods and dead sages into the affairs of men; report miraculous feats and occurrences; and come into conflict with one another in regard to many biographical details…

The trouble comes only when mythological accounts are taken as meticulously factual and men begin to be dogmatic about the versions presented in them. In the mythological literary technique, facts are often inflated with the emotional overtones and with the artistic expressiveness that their impact has elicited from human consciousness, and we have therefore to seek their message in the total effect they produce and not through a cocksure attitude towards the happenings in space and time…

this is only one of the following ten Sankara-vijayas listed on p. 32 of T.S. Narayana Sastri’s The Age of Sankara…Of these, the first two, the Brihat-Sankara-vijaya and Prachma-Sankara-vijaya are supposed to be the products of the contemporaries of Sankara, their authors being the Acharya’s disciples. Nothing can be said of this claim, as the texts are not available anywhere at present.' Sri T. S. Narayana Sastri, the author of The Age of Sankara, claims to have come across what he calls a ‘mutilated copy’ of the second section, called Sankaracharya-satpatha, of Chitsukha’s work mentioned above. There is, however, no means to assess the authenticity of the claim on behalf of this mutilated copy, as it is not available anywhere…

there are only five of them available in printed form, and even most of them can be got only with considerable difficulty….

We are taking up for translation the last of these, namely, Madhava-Vidyaranya’s work, with the full awareness of its limitations, which may be listed as follows: It is not a biography but a biographical and philosophical poem, as the author himself calls it. There are many obviously mythological elements in it, like reports of conferences held in heavens, appearance of Devas and dead sages among men, traffic between men and gods, thundering miracles, and chronological absurdities which Prof. S. S. Suryanarayana condemns as ‘indiscriminate bringing together of writers of very different centuries among those whom Sankara met and defeated.’ But these unhistorical features it shares with all other available Sankara-vijayas, including that of Anantanandagiri….Ever since it was first printed in Ganapat Krishnaji Press in Bombay in the year 1863, it has continued to be a popular work on Sankara and it is still the only work on the basis of which ordinary people have managed to get some idea of the great Acharya, in spite of the severe uncharitable criticism1 [The motives behind the criticism of Madhviya-sankara-vijaya and the scurrilous nature of the criticism will be evident from the following extract from page 158 of The Age of Sankara by T. S. Narayana Sastri (1916): “We know from very reliable sources that this Madhaviya-Sankara-vijaya was compiled by a well-known Sanskrit scholar who passed away from this world just about eight years ago, under the pseudonym of ‘Madhava’— a 'synonym' for ‘Narayana’—specially to extol the greatness of the Sringeri Math, whose authority had been seriously questioned by the Kumbhakonam Math, the Acharyas of the latter Math claiming exclusive privilege of being entitled to the title of the 'Jagadgurus' for the whole of India as being the direct successors of Sri Sankara Bhagavatpada's own Math established by him at Kanchi, the greatness of which had been unnecessarily extolled by Rajachudamani Dikshita, Vallisahaya Kavi and Venkatarama Sarman in their respective works, Sankarabhyudaya, Achraya-dig-vijaya and Sankara-bhagavatpadacharitra. About fifty years ago, in the very city of Madras, as many may still remember, a fierce controversy raged between the adherents of the Kumbhakonam Math on the one hand, and those of the Sringeri Math headed by Bangalore Siddhanti Subrahmanya Sastri and two brothers —Kumbhakonam Srinivasa Sastri and Kumbhakonam Narayana Sastri—sons of Ramaswami Sastri, a protege of the Sringeri Math, on the other. We have very strong reasons to believe that this Sankara-dig-vijaya ascribed to Madhava, the Sankara-vijaya-vilasa ascribed to Chidvilasa, and the Sankara-vijaya-sara ascribed to Sadananda, had all been brought into existence by one or other of these three scholars, about this period, in answer to the Sankara-vijayas ascribed to Rajachudamani Dikshita and Vallisahaya Kavi.” Not satisfied with the above indictment, Sri T. S. Narayana Sastri gives the following bazaar gossip as proof of his contention on page 247 of his book, “The reader is also referred to an article in Telugu with the caption Sankara-vijaya-karthavevaru by Veturi Prabhakara Sastri of Oriental Manuscripts Library, Madras, published in the Literary Supplement of the Andhra Patrika of Durmathi Margasira (1921-22) where an interesting note about the author of the above mentioned ‘Sankara Vijaya’ (Sanakara-dig-vijaya of Madhava) is given. Here is an English rendering of a portion of that article: ‘I happened to meet at Bapatla, Brahmasri Vemuri Narasimha Sastri, during my recent tour in the Guntur District, in quest of manuscripts. I mentioned casually to him my doubts regarding the authorship of Madhaviya-sankara-vijaya. He revealed to me some startling facts. When he was at Madras some fifteen years ago, he had the acquaintance of the late Bhattasri Narayana Sastri who wrote the Sankara Vijaya published in the name of Madhava i.e., Vidyaranya, and that four others helped him in this production. The importance of the Sringeri Mutt is very much in evidence in this Sankara Vijaya (not correct). Taking a copy of the Vyasachala Grantha, available at Sringeri Mutt, Bhattasri Narayana Sastri made alterations here and there and produced the Sankara-vijaya in question. That he was an expert in such concoctions, is widely known among learned men.”…

The criticism of it is uncharitable because it is mainly born of prejudice, and it has extended beyond finding fault with the text, to the question of its authorship itself. The critics somehow want to disprove that this work is, as traditionally accepted, a writing of the great Madhava-Vidyaranya, the author of the Panchadasi, and a great name in the field of Indian philosophical and theological literature….Besides the support of tradition, the colophon at the end of every chapter of the book mentions its author’s name as Madhava, that being the pre-monastic name of Vidyaranya….

The identity of Madhava, the author of Sankara-dig-vijaya, with this Madhava-Vidyaranya is further established by the first verse of the text, wherein he pays obeisance to his teacher Vidyatirtha…The identity is further established by the poet Madhava’s reference to his life in the royal court in the following touching introductory verses of his work: “By indulging in insincere praise of the goodness and magnanimity of kings, which are really non-existent like the son of a barren woman or the horns of a hare, my poesy has become extremely impure. Now I shall render it pure and fragrant by applying to it the cool and fragrant sandal paste fallen from the body of the danseuse [a female ballet dancer] of the Acharya’s holy fame and greatness, as she performs her dance on the great stage of the world.”

Besides, the text is a masterpiece of literature and philosophy, which none but a great mind could have produced. But there are detractors of this great text who try to minimise its obvious literary worth by imputing plagiarism and literary piracy to its author. They claim that they have been able to show several verses that have entered into it from certain other Sankara-vijayas like Prachina-Sankara-vijaya and Vyasachala’s Sankara-vijaya. Though Prachina-Sankara-vijaya is nowhere available, T. S. Narayana Sastri claims to have in his possession some mutilated sections of it; but such unverifiable and exclusive claims on behalf of mutilated texts cannot be entertained by a critical and impartial student of these texts, since considerations other than the scholarly have entered into these criticisms, and manuscripts, too, have been heavily tampered with by Sanskrit Pandits. It can as well be that the other Vijayas have taken these from the work of Madhava. Next, even if such verses are there, and they are demonstrably present in regard to Vyasachala’s work, the author can never be accused of plagiarism, because he acknowledges at the outset itself, that his work is a collection of all the traditions about Sankaracharya and that in it all the important things contained in an extensive literature can be seen in a nutshell as an elephant’s face in a mirror…

Besides, it is forgotten by these critics that it is a literary technique of Vidyaranya, as seen from his other works also, to quote extensively from recognised authorities without specially mentioning their names, and that this feature of the present work goes only to establish the identity of its authorship with Vidyaranya….

There is also the view that the author need not necessarily be Madhava-Vidyaranya but Madhavacharya, the son of the former’s brother Sayana and the author of Sarvadarsana-Samgraha, a masterly philosophical text. To make this hypothesis even plausible, it has to be established that this Madhava was the disciple of Vidyatirtha, which the author of Sankara-dig-vijaya claims to be in the very first verse of the text…

Most of Vidyaranya’s other works are on high philosophical and theological themes, and if he has used methods and styles in such works differing from that of a historical poem like Sankara-dig-vijaya, it is only what one should expect of a great thinker and writer. That the author of this work has poetic effect very much in view can be inferred from his description of himself as Nava-Kalidasa (a modern Kalidasa) and his work as Navakalidasa-santana (offspring of the modern Kalidasa)…

Chronology and historicity did not receive much attention from even the greatest of Indian writers in those days.

Regarding the biographical details contained in different Sankara-vijayas, there are wide variations, as already pointed out. There is no way now of settling these differences…

Every date in ancient Indian history, except that of the invasion of Alexander (326 B.C.), is controversial, and Sankara’s date is no exception. Max Muller and other orientalists have somehow fixed it as 788 to 820 A.D., and Das Gupta and Radhakrishnan, the well-known writers on the history of Indian Philosophy, have accepted and repeated it in their books. To do so is not in itself wrong, but to do it in such a way as to make the layman believe it to be conclusive is, to say the least, an injustice to him. It is held by the critics of this date that the Sankara of 788-820 A.D. is not the Adi-Sankara (the original Sankara), but Abhinava Sankara (modern Sankara), another famous Sannyasin of later times (788-839), who was born at Chidambaram and was the head of the Sankara Math at Kanchipuram between 801 and 839. He was reputed for his holiness and learning and is said to have gone on tours of controversy (Dig-vijaya) like the original Sankara.

It is found that not only modern scholars, but even the authors of several Sankara-vijayas have superimposed these two personalities mutually and mixed up several details of their lives. The author of the concept of adhyasa himself seems to have become a victim of it! The cause of much of this confusion has been the custom of all the incumbents of the headship of Sankara Maths being called Sankaracharyas. To distinguish the real Sankara, he is therefore referred to as ‘Adi-Sankara' an expression that is quite meaningless. For, Sankaracharya was the name of an individual and not a title, and if the heads of the Maths of that illustrious personage were known only by their individual names like the heads of religious institutions founded by other teachers, probably much of this confusion could have been avoided….

Ullur S. Parameswara Iyer has pointed out in his great work that the sole support for the modern scholars’ view on Sankara’s date as 788 A.D. is the following incomplete verses of unknown authorship: "Nidhi nagebha vahnyabde vibhave sankarodayah; Kalyabde candranetranka vahnyabde pravisad guham; Vaisakhe purnimayam tu sankarah sivatamagat." Here the words of the first verse are the code words for the year 3889 of the Kali era, which is equivalent to 788 A.D. (It is derived as follows: nidhi: 9; naga: 8; ibha: 8; vahni: 3. Since the numbers are to be taken in the reverse order, it gives 3889 of the Kali era as the date of Sankara’s birth, its conversion into Christian era being 788 A.D. Kali era began 3102 years before the Christian era….

Traditional Indian dates are suspect because of the multiplicity of eras, of which about forty-seven have been enumerated by T. S. Narayana Sastri in his book, The Age of Sankara. So unless the era is specifically mentioned, it is difficult to fix a date in any understandable way. Two of these eras are famous—the Kali era, which started in 3102 B.C., and Yudhishthira Saka era which started 37 years after, i.e., in 3065 B.C. The calculation according to the latter era is, however, complicated further by the fact that, according to the Jains and the Buddhists, the latter era started 468 years after the Kali era, that is, in 2634 B.C.

Sri T. S. Narayana Sastri, in his book, The Age of Sankara, argues the case for the traditional date, on the basis of the list of succession kept in Kamakoti Math and Sringeri Math, and what he has been able to gather from ‘mutilated copies’ of Brihat-Sankara-vijaya, Prachtna-Sankara-vijaya and Vyasachallya-Sankara-vijaya. Until authentic copies of these works are available, the information they are supposed to give is not acceptable…

44 B.C., the supposed date of the birth of Sankara according to Sringeri Math, might have been the result of the confusion of eras and calculations based on them. 2625 of the Kali era, the date of his death, must have been taken as referring to Buddhist-Jain era and then converted into Kali era by adding 468 to it, thus arriving at 3093 of Kali era (9 or 10 B.C.) as the date of Sankara’s death….

as stated in T. S. Narayana Sastri’s work, in the Kamakoti list Sankara occupied that Gaddi for three years (from 480 B.C. to 477 B.C.) and was followed by Sureswara for 70 years (477 B.C. to 407 B.C.), the Sringeri list maintains that Sankara occupied that Gaddi for six years (from 18 B.C. to 12 B.C.), and was followed by Sureswara for 785 years (from 12 B.C. to 773 A.D.)… The record of the Sringeri Math says that Sankara was born in the 14th year of the reign of Vikramaditya. Compilers wrongly referred this to the era of Vikramaditya of Ujjain, which was originally called Malava Samvat and later in the eighth century A.D. called the Vikrama Samvat. This took Sankara to the first century B.C. and necessitated the assignment of around 800 years to Sureswaracharya to agree with the later dates. Mr L. Rice points out that the reference is not to the Vikramaditya of Ujjain but to the Chalukya king Vikramaditya who ruled in Badami near Sringeri. Historians opine that Chalukya Vikramaditya ascended the throne during the period 655 to 670 A.D….

Such unbelievable inconsistencies have made modern historians totally reject the evidence provided by the chronological lists of the Maths. So Sri Ullur Parameswara Iyer, himself a pious Brahmana, maintains in his History of Kerala Sahitya (Vol. 1 p. 111) that it is easy to prove that most of these Math lists have been formulated so late as the 16th century A.D.

But a still greater difficulty posed for such an early date as 509 to 476 B.C. for Sankara is the proximity of this to the generally accepted date of the Buddha (567-487 B.C.). Sankara has criticised Buddhism in its developed form with its four branches of philosophy. A few centuries at least should certainly be allowed to elapse for accommodating this undeniable fact. Sri T. S. Narayana Sastri is, however, remarkably ingenious, and his reply to this objection is that the Buddha’s date was certainly much earlier. Vaguely quoting Prof. Wheeler, Weber and Chinese records, he contends that the Buddha must have flourished at any time between the 20th and the 14th century B.C. He challenges the fixing of the date of Buddha on the basis of the dates of Kanishka or of Megasthenes.3a [Kanishka’s date is variously stated as 1st century B.C., 1st century A.D., 2nd century A.D. and 3rd century A.D. The relevancy of his date to the Buddha’s date is that Hsuan Tsang, the Chinese traveller, states that the Buddha lived four hundred years before Kanishka. Some historians try to fix the date of the Buddha on the basis of this information as 5th century B.C. This view is not currently accepted, and the Buddha’s date is settled on other grounds as 567-487 B.C. It is fixed so on the basis of Asoka’s coronation in 269 B.C., four years after his accession. According to the Ceylon Chronicles, 218 years separate this event of Asoka’s coronation from the date of the Buddha’s demise. Thus we get 487 as the date of the Buddha’s demise, and as he is supposed to have lived 80 years, the date of his birth is 567. According to R. Sathianatha Ayyar, the date of 487 B.C. is supported by “the dotted record” of Canton (China); The traditional date according to the Buddhist canonical literature, however, is 623-543 B.C. Megasthenes comes into the picture, because he was the Greek Ambassador of Selukos Nickator at the court of Chandra Gupta Maurya (325 B.C.), who is described by him as Shandracotus. Now Sri T. S. Narayana Sastri, with a view to push back the Buddha’s date, challenges this identification, and opines that this reference could as well be to Chandra Gupta or even to Samudra Gupta of the Gupta dynasty (300-600 A.D.), in which case the Mauryan age (325 to 188 B.C.) will have to be pushed further back into the 7th to 5th century B.C. and the Buddha (567-487 B.C.) too, into the 9th century B.C. at least. But Sri Sastri forgets that these contentions cannot stand, as the date of Megasthenes and of Chandra Gupta Maurya have necessarily to be related to the firm and unquestionable date of Alexander’s invasion of India (326 B.C.) Megasthenes was the ambassador at the Pataliputra court sent by Selukos Nickator (305 B.C.), the Satrap who succeeded to the Indian region of Alexander’s empire, which he had to give up to Chandra Gupta by a treaty. T. S. Narayana Sastri’s attempt to shift the Gupta period of India history, to the time of Alexander’s invasion (326 B.C.) by equating Shandracotus with Samudra Gupta of the Gupta period, is a mere chronological guess-work without any supporting evidence, as against several historical synchronisms which compel the acceptance of the currently recognised chronology. For example, the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Fahien was in India in the Gupta age, from 399-414 A.D., and his description of India can tally only with that period and not with the Mauryan period. Besides, the Hun invasion of India was in the reign of Skanda Gupta, about 458 A.D., and this event cannot be put on any ground into the B.C.’s when Mauryans flourished, even with an out-stretched poetical imagination. So we have got to maintain that the Shandracotus who visited Alexander’s camp (326 B.C.) and who later received about 326 B.C. Megasthenes as the ambassador of Selukos Nickator, the successor to Alexander’s Indian province, can be none other than Chandra Gupta of the Mauryan dynasty (325 B.C. to 188 B.C.) Further, historical synchronisms, the sheet-anchor of the chronology of Indian history give strong support to the accepted date of Asoka (273-232 B.C.), the greatest of the Mauryan Emperors. His Rock Edict XIII mentions, as stated by Sathianatha Ayyar, the following contemporary personalities: Antiochus Teos of Syria (261-246 B.C.); Ptolemy Philadelphos of Egypt (285-247 B.C.); Antigonos Gonates of Macedonia (278-239 B.C.); Magas of Cyrene (285-258 B.C.), and Alexander of Epirus (272-258 B.C.). They are referred to as alive at the time of that Rock Edict. In the face of such historical synchronisms all attempts to push back the time of the Buddha by several centuries in order to substantiate the theory of 509 B.C. being Sankara’s date, is only chronological jugglery. So the Buddha’s date has to remain more or less as it is fixed today (568-487 B.C.). Sankara came definitely long after the Buddha.] The reference to Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador, who refers to the ruler to whom he was accredited as Shandracotus, need not necessarily be to Chandragupta Maurya but to the king of the Gupta dynasty (300-600 A.D.) with the same name, or even to Samudra Gupta. If this line of argument is accepted, the present dates of Indian history will have to be worked back to about three to four hundred years, which will land us in very great difficulties, as shown in the foot note….

there is another opinion that assigns Sankara to the 1st century B.C. This view is held by Sri N. Ramesam in his book Sri Sankaracharya (1971). His argument is as follows: Sankara is accepted in all Sankara-vijayas as a contemporary of Kumarila. Kumarila must have lived after Kalidasa, the poet, because Kumarila quotes Kalidasa’s famous line; Satam hi sandeha padesu vastusu pramanam antahkaranasya vrittayah. Now Kalidasa’s date has not been firmly fixed (first half of the 5th century A.D. according to some), but it is contended that it cannot be earlier than 150 B.C., as Agni Mitra, one of the heroes in a famous drama of Kalidasa, is ascribed to that date. So also, it cannot be later than the Mandasor Inscription of 450 A.D. So on the basis that Sankara and Kumarila were contemporaries and that Kumarila came after Kalidasa, we have to search for Sankara’s date between 150 B.C. and 450 A.D. Now to narrow down the gap still further, the list of spiritual preceptors that preceded Sankara is taken into consideration. Patanjali, Gaudapada, Govindapada and Sankara— form the accepted line of discipleship. Patanjali, Sri Ramesam contends, lived in the 2nd century B.C., a conclusion which, if accepted finally (?), gives much credence to his theory. Now, not less than a hundred years can be easily taken as the distance in time between Sankara and Patanjali in this line of succession, and thus we derive the time of Sankara as the 1st century B.C., which has the merit of being in agreement with the Kumarila-Sankara contemporaneity and the Kumarila-Kalidasa relationship. The 1st century hypothesis has also got the advantage of tallying with the Sringeri Math’s teacher-disciple list, according to which, as already stated, 12 B.C. is the date of Sankara’s demise. Sri Ramesam finds further confirmation for his theory in the existence of a temple on a Sankaracharya Hill in Kashmir attributed to Jaluka, a son of Asoka who became the ruler of Kashmir after Asoka’s demise, according to Rajaiarangini. Asoka passed away In 180 B.C. and it is very credible that Jaluka could have been in Kashmir when Sankara visited that region, provided Sankara’s life is fixed in the 1st century B.C. Further, Cunningham and General Cole are stated to assign the temple architecturally to the times of Jaluka…

Sri Ramesam also refutes the modern scholars’ view of Sankara’s date being 788-820 A.D. on the ground that this has arisen due to confusion between Adi-Sankara and Abhinava-Sankara (788-840 A.D.)… its credibility depends largely on the theory of 200 B.C. being the time of Patanjali and the acceptance of the Kumarila-Kalidasa relationship. If these are questioned, the whole theory falls. This is the case with most dates in Indian history, where the rule is to fix the date of one person or event on the basis of the date of another person or event, which itself is open to question….

Dr. A. G. Krishna Warrier, Professor of Sanskrit (Rtd) in the Kerala University, in his learned Introduction to his translation of Sankara’s Brahma-sutra-bhashya into Malayalam… states that the Buddhist author Kamalasila has pointed out that Sankara has quoted in his Brahma-sutra-bhashya (B. S. II. 2-28) the following passage from the Alambanapariksha by Dingnaga, the celebrated Buddhist savant: 'Yadantarjneyarupam tat bahiryadavabhasate’. Dingnaga’s date, which Dr. Warrier links with those of Vasubandhu (450 A.D.) and Bhartrhari, is fixed by him as about 450 A.D. But that is not all. The following verse of Dingnaga’s commentator Dharmakirti is quoted by Sankara in his work Upadesa-sahasri: Abhinnopi hi buddhydtma viparyasitadarsanaih grahyagrahaka-samvitti bhedavaniva laksyate (ch. 18, v. 142). This reference is from Dharmakirti’s Pramana-virtischhaya. Dr. Warrier points out that Dharmakirti is described as a ‘great Buddhist logician’ by the Chinese pilgrim-traveller, It-sing, who was in India in 690 A.D. The implication is that Dharmakirti must have lived in the first half of the 7th century or earlier, and that Sankara came after him. It means that Sankara’s date cannot be pushed back beyond the 5th century A.D., or even beyond the 7th century A.D., if the Upadesasahasri is accepted as a genuine work of Sankara. As in the case of most dates in Indian history, the credibility of the view, too, depends on the acceptance of the dates of Dingnaga and Dharmakirti as 5th century and 7th century respectively, and that Upadesasahasri is really a work of Sankara, as traditionally accepted. Fixing dates on the basis of other dates, which are themselves open to question, can yield only possibilities and not certainties.

Probable dates suggested by other scholars are also the 6th century and the 7th century A.D. Sankara refers in his writings to a king named Pumavarman who, according to Hsuan Tsang, ruled in 590 A.D. It is, therefore, contended that Sankara must have lived about that time or after. Next Telang points out how Sankara speaks of Pataliputra in his Sutra-bhashya (IV. ii. 5) and that this will warrant Sankara having lived about a century before 750 A.D., by which time Pataliputra had been eroded by the river and was non-existent. Such references to names of persons, cities, rivers, etc. in philosophical writings can also be explained as stock examples, as we use Aristotle or Achilles in logic, and need not necessarily have any historical significance. Dr. T. R. Chintamani maintains that Kumarila lived towards the latter half of the 7th century A.D. (itself a Controversial point) and Sankara, being a contemporary of his, must have lived about that time (655-684 A.D.). It is also pointed out by him that Vidyananda, the teacher of Jainasena, who was also the author of Jaina-harivamsa (783 A.D.), quotes a verse4 ["Atmapi sadidam brahma mohat parosyadu sitam; Brahmapi sa tathaivatma sadvitiyatayesate."] from the Brihadaranyaka-vartika of Sureswara, disciple of Sankara. This is impossible to conceive without granting that Sankara and Sureswara lived, about a hundred years earlier to Jainasena who lived about the second half of the 8th century A.D.

Thus vastly varied are the views about Sankara’s date, ranging from 509 B.C. to 788 A.D., i.e., more than a millennium and a half…

Under the circumstances, all these complicated discussions of Sankara’s date culminate only in a learned ignorance. We have to admit that we have no certain knowledge, and it is, therefore, wise not to be dogmatic but keep an open mind….

It is pointed out in the monograph of P. Rama Sastry on The Maths Founded by Sankara that this four-Math theory has been propounded first in Chidvilasa’s Sankara-vijaya which, along with some other Sankara-vijayas, is, according to T. S. Narayana Sastri, a recent production and of little authority. It finds no support in the other Vijayas of its kind and perhaps not even in the more ancient Sankara-vijayas. Of course this view cannot be verified now, as the most ancient of these Sankara-vijayas are not available now….

Nothing more precise than this can be said about the question as to which are the Maths originally founded by Sankaracharya, or even whether he founded any Math at all. Different sectaries having varying traditions can stick to them with justification, provided they do not become too cocksure and dogmatic and deny a similar right to others who differ from them…

it is interesting to read the following statement issued by Sri T. N. Ramachandran, Rtd. Joint Director-General of Archaeology of India…“At Kedamath, on the way to Badrinath, there is a monument associated with the great Adi-Sankaracharya which His Holiness Sri Sankaracharya of Dwaraka Pith visited some time ago and expressed a desire to renovate (the memorial). His Holiness issued instructions to scholars of all parts of our country to ascertain the place of the Samadhi of the great Adi- Sankaracharya. On this Sri Sampurnanand, the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, and myself bestowed some thought.

“After having arrived at some conclusion on the point by mutual correspondence, we are of the opinion, that Kedamath cannot be said to be the Samadhisthan (the final resting place) of the great Acharya….

‘‘The Memorial at Kedamath should at any rate be kept intact, and it is the duty of all who profess any interest in the hoary Religion and Philosophy of our land to join hands in the sacred endeavour of renovating the Adi-Sankara Memorial at Kedarnath, as chalked out by Sri Sampurnanand, the Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh, in his letter addressed to me…‘Dear Sri Ramachandra, Recently I had occasion to discuss the matter with the Sankaracharya of Dwaraka Pith also. In the first place the word ‘Samadhi’ is a misnomer in this connection. There is nothing to prove that Sri Sankaracharya died at this spot. All that tradition says is that he came to Kedarnath and, in modern phraseology, disappeared thereafter. So, what is "called Samadhi' is really not a Samadhi but a Memorial. I myself do not treat it as Samadhi and such proposals as I am considering are based on this information. What I propose is that instead of the wretched structure that passes as a Samadhi, a new Memorial should be built in memory of the great Acharya. It should not occupy the place of the present construction which is in danger of being overwhelmed by an avalanche any day. It should be built at a safer place somewhere near the temple. I am getting a design prepared by our State Architect. The Sankaracharya of Dwaraka Pith has given me his support in the matter’....”

This theory of Sankara having attained Siddhi (final end) at Kanchi is supported, according to T. S. Narayana Sastri in his book, The Age of Sankara, by the following texts: Brihat Sankara- vijaya, Vyasachala’s Sankara-vijaya and Anantanandagiri’s Sankara-vijaya, besides the Punyasloka Manjari, Jagat-guru-ratnamala and Jagat-guru-katha samgraha. On this it has to be remarked that from among the above-mentioned Sankara-vijayas one has only Anantanandagiri’s and Vyasachala’s works available for reference and corroboration. Sri T. S. Narayana Sastri, however, claims to possess some extracts of mutilated sections of the first of the texts mentioned, which is considered by some as the most ancient and authoritative text. But no one can be sure of, much less accept, the claims of these mutilated manuscripts….

The attainment of Siddhi at Kanchi is further corroborated by Sivarahasya, a voluminous text of the Siva cult dealing with all the devotees of Siva, which is also quoted in the Madras University edition of Anantanandagiri. It has, however, to be remarked that, as pointed out by T. S. Narayana Sastri (pp. 287 of his work The Age of Sankara), there are conflicting readings on this point in different manuscripts of the text of Sivarahasya. In one it is: misran tato lokam avapa saivam. In another it is: misran sa kancyam. In still another it is: Kancyam Sive! tava pure sa ca siddhim apa. Evidently texts have been manipulated by interested Pandits, creating a very confusing and suspicious situation….

In the edition of it, recently published by the University of Madras under the editorship of Dr. Veezhinathan, the birth of Sankara is thus described…

But the first ever published edition of this work gives an entirely different version….

Now, in Dr. Veezhinathan’s edition, the above text is given as a footnote….he refers to ten manuscripts (A.Mss.) as supporting his version. Probably many of these manuscripts of both groups may be copies only, and from the numbers, their authenticity cannot be ascertained. Besides, several of them are not complete also…The Editors of the 1868 edition, Navadweep Goswami and Jayanarayana Tarkapanchanana, have stated in their Preface that ‘their edition had been prepared in the light of three texts they could get—one in Nagari letters which was procured with great difficulty; another in Telugu characters procured with equal difficulty; and still another in Bengali alphabets made on the basis of the above texts’. There is no reason why this text should not be given at least an equal place of importance as the one edited by Dr. Veezhinathan. According to the text of the Calcutta edition, Anantanandagiri is giving the history, not of ‘Adi-Sankara who was born at Kaladi’, but of a Sankaracharya ‘who was born immaculately to Visishta of Chidambaram’, who continued to live at Chidambaram itself, took Sannyasa there, and who went on Dig-vijaya tours that are entirely different from the routes that Adi-Sankara is supposed to have taken in several of the other Vijayas. This Sankara is very largely concerned with reforming the various cults that prevailed, in the country and very little with philosophy. The controversy with Mandana, which is one of the most glorious episodes in Adi-Sankara’s life, finds a casual mention in the form of a synopsis. In this, as also in entering into Amaruka’s body and in the writing of the Bhashyas, the two Sankaracharyas are mixed up….There is every possibility that this Chidambaram Sankaracharya is the Abhinava-Sankara whom even modern scholars have mistakenly identified with Adi-Sankara and given 788 A.D. as his time. Besides, Anantanandagiri, the author, calls the hero of his work his Parama-guru (his teacher's teacher). This makes the matter all the more confusing. For, no one has recorded that Adi-Sankara or his disciples had a disciple called Anantanandagiri. Anandagiri (quite different from Anantanandagiri) was Sankara’s disciple, and the Prachina-Sankara-vijaya attributed to him (a book quite different from Anantanandagiri’s) is not available anywhere now….no final view is possible with the existing information. The best that can be said is that it is one of the traditions….

We have shown above the confusion prevailing about the place of Sankara’s demise. The same extends to most events of his life, especially about the places where they happened and about the routes he took in his travels….

the custom of all the Heads of Sankara Maths being called as Sankara-charyas, as if it were a title, and not an individual’s name, was the main cause of much of this confusion of biographical and literary details connected with Sankara. This confusion has got worse confounded by the interference with manuscript copies in the past by the adherents of particular Sankara Maths in order to enhance the prestige and supremacy of the particular institution that patronised them. As a result, we have today only a lot of traditions about Sankaracharya, and he is a foolhardy man, indeed, who dares to swear by any of these traditions as truly historical and the others as fabricated…

Rightly does Dr. Radhakrishna offer the tribute of the Indian mind to the personality of the great Acharya in the following most beautiful and effective words in his book on Indian Philosophy: “The life of Sankara makes a strong impression of contraries. He is a philosopher and a poet, a savant and a saint, a mystic and a religious reformer. Such diverse gifts did he possess that different images present themselves, if we try to recall his personality. One sees him in youth, on fire with intellectual ambition, a stiff and intrepid debator; another regards him as a shrewd political genius (rather a patriot) attempting to impress on the people a sense of unity; for a third, he is a calm philosopher engaged in the single effort to expose the contradictions of life and thought with an unmatched incisiveness; for a fourth, he is the mystic who declares that we are all greater than we know. There have been few minds more universal than his.”

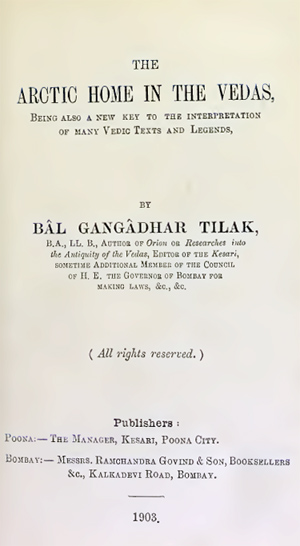

-- Sankara-Dig-vijaya: The Traditional Life of Sri Sankaracharya, by Madhava-Vidyaranya, Translated by Swami Tapasyananda

Highlights:

The historical fame and cultural influence of Shankara may have grown centuries later after his death, particularly during the era of Muslim invasions and consequent devastation of India….

He established the importance of monastic life…

There are at least fourteen different known biographies of Adi Shankara's life….

These, as well as other biographical works on Shankara, were written many centuries to a thousand years after Shankara's death…the biographies are filled with legends and fiction, often mutually contradictory….

[O]ne of the most cited Shankara hagiographies, Anandagiri's, includes stories and legends about historically different people, but all bearing the same name of Sri Shankaracarya or also referred to as Shankara but likely meaning more ancient scholars with names such as Vidya-sankara, Sankara-misra and Sankara-nanda. Some biographies are probably forgeries by those who sought to create a historical basis for their rituals or theories.

Adi Shankara died in the thirty third year of his life…

The Sringeri records state that Shankara was born in the 14th year of the reign of "Vikramaditya", but it is unclear as to which king this name refers…

Several different dates have been proposed for Shankara:

• 509–477 BCE…

• 44–12 BCE…

• 6th century CE…

• c. 700 – c. 750 CE…

• 788–820 CE…

• 805–897 CE… it would not have been possible for him to have achieved all the works apportioned to him…

The biographies vary in their description of where he went, who he met and debated and many other details of his life…Different and widely inconsistent accounts of his life include diverse journeys, pilgrimages, public debates, installation of yantras and lingas, as well as the founding of monastic centers in north, east, west and south India…

Texts say that he was last seen by his disciples behind the Kedarnath temple, walking in the Himalayas until he was not traced…

[H]is doctrine, states Sengaku Mayeda, "has been the source from which the main currents of modern Indian thought are derived". Over 300 texts are attributed to his name, including commentaries (Bhāṣya), original philosophical expositions (Prakaraṇa grantha) and poetry (Stotra). However most of these are not authentic works of Shankara and are likely to be by his admirers or scholars whose name was also Shankaracharya…

Shankara only accorded a provisional validity to the knowledge gained by inquiry into the words of the Śruti (Vedas) and did not see the latter as the unique source (pramana) of Brahmajnana. The affirmations of the Śruti, it is argued, need to be verified and confirmed by the knowledge gained through direct experience (anubhava) and the authority of the Śruti, therefore, is only secondary…

Shankara maintained the need for objectivity in the process of gaining knowledge (vastutantra), and considered subjective opinions (purushatantra) and injunctions in Śruti (codanatantra) as secondary. Mayeda cites Shankara's explicit statements emphasizing epistemology (pramana-janya) in section 1.18.133 of Upadesasahasri and section 1.1.4 of Brahmasutra-bhasya. According to Michael Comans (aka Vasudevacharya), Shankara considered perception and inference as a primary most reliable epistemic means [Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge. Epistemologists study the nature, origin, and scope of knowledge, epistemic justification, the rationality of belief, and various related issues.], and where these means to knowledge help one gain "what is beneficial and to avoid what is harmful", there is no need for or wisdom in referring to the scriptures….

Shankara…states that for proper understanding one must "accept only meanings that are compatible with all characteristics" and "exclude meanings that are incompatible with any"…

Shankara…discourages ritual worship such as oblations to Deva (God), because that assumes the Self within is different from the Brahman. The "doctrine of difference" is wrong, asserts Shankara, because, "he who knows the Brahman is one and he is another, does not know Brahman". However, Shankara also asserts that Self-knowledge is realized when one's mind is purified by an ethical life that observes Yamas such as Ahimsa (non-injury, non-violence to others in body, mind and thoughts) and Niyamas. Rituals and rites such as yajna (a fire ritual), asserts Shankara, can help draw and prepare the mind for the journey to Self-knowledge. He emphasizes the need for ethics such as Akrodha and Yamas during Brahmacharya, stating the lack of ethics as causes that prevent students from attaining knowledge….

[H]is Advaitin convictions with a monistic view of spirituality….I am Consciousness, I am Bliss…

Without hate, without infatuation, without craving, without greed;

Neither arrogance, nor conceit, never jealous I am..

Neither mantra, nor rituals, neither pilgrimage, nor Vedas…

Without fear, without death, without discrimination, without caste;

Neither father, nor mother, never born I am;

Neither kith, nor kin, neither teacher, nor student am I…

Without form, without figure, without resemblance am I…

According to Shankara, the one unchanging entity (Brahman) alone is real, while changing entities do not have absolute existence…

His philosophical thesis was that jivanmukti is self-realization, the awareness of Oneness of Self and the Universal Spirit called Brahman…

The method of yoga, encouraged in Shankara's teachings notes Comans, includes withdrawal of mind from sense objects as in Patanjali's system, but it is not complete thought suppression, instead it is a "meditative exercise of withdrawal from the particular and identification with the universal, leading to contemplation of oneself as the most universal, namely, Consciousness"…

Sankara also emphasized the need for and the role of Guru (Acharya, teacher) for such knowledge.

Shankara's Vedanta shows similarities with Mahayana Buddhism; opponents have even accused Shankara of being a "crypto-Buddhist”…

Sankara recognizes the value of the law of contrariety and self-alienation from the standpoint of idealistic logic; and it has consequently been possible for him to integrate appearance with reality…

Shankara and his followers borrowed much of their dialectic form of criticism from the Buddhists. His Brahman was very much like the sunya of Nagarjuna [...] The debts of Shankara to the self-luminosity of the Vijnanavada Buddhism can hardly be overestimated. There seems to be much truth in the accusations against Shankara by Vijnana Bhiksu and others that he was a hidden Buddhist himself. I am led to think that Shankara's philosophy is largely a compound of Vijnanavada and Sunyavada Buddhism with the Upanisad notion of the permanence of self superadded….

He travelled all over India to help restore the study of the Vedas….

He introduced the Pañcāyatana form of worship, the simultaneous worship of five deities – Ganesha, Surya, Vishnu, Shiva and Devi. Shankara explained that all deities were but different forms of the one Brahman, the invisible Supreme Being….

Hajime Nakamura states that the early Vedanta scholars were from the upper classes of society, well-educated in traditional culture. They formed a social elite, "sharply distinguished from the general practitioners and theologians of Hinduism." Their teachings were "transmitted among a small number of selected intellectuals". Works of the early Vedanta schools do not contain references to Vishnu or Shiva….

The Buddhist scholar Richard E. King states, “Although it is common to find Western scholars and Hindus arguing that Sankaracarya was the most influential and important figure in the history of Hindu intellectual thought, this does not seem to be justified by the historical evidence.”…

Other scholars state that the historical records for this period are unclear, and little reliable information is known about the various contemporaries and disciples of Shankara…

Several scholars suggest that the historical fame and cultural influence of Shankara grew centuries later, particularly during the era of Muslim invasions and consequent devastation of India. Many of Shankara's biographies were created and published in and after 14th century…[Note: 0 Reference to "Prajna"; 1 Reference to "Consciousness" in Rig Veda, translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith: "The Swift Ones favour him who purifieth this: with consciousness they stand upon the height of heaven."]

[Note: 0 Reference to "I am Brahman" in The Texts of the White Yajurveda, translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith

4 References to "I am": (1) I am in heaven above; (2) I am what Gods in secret hold the highest; (3) I am the Household priest; (4) I am the triple light, the region's meter.]

[Note: 0 Reference to "I am Brahman" in The Veda of the Black Yajus, translated by Arthur Berriedale Keith

7 References to "I am": (1) As wife with my husband I am united; (2) What time thou didst declare, 'I am Cipivista'?; (3) Favour those in the region where I am; (4) Whose domestic priest I am; (5) 'I am he who smites in the stronghold; (6) 'I am he who brings from the stronghold'; (7) 'I am the friend of all'.]

[Note: 0 References to "Tatt" or "That thou art" in Hymns of the Samaveda, translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith]

[Note: 0 References to "Ayamatma" or "Atman" in The Hymns of the Artharvaveda, translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith].

-- Adi Shankara, by Wikipedia