Part 2 of 2

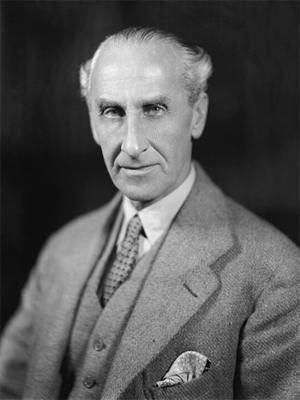

Conducting styleFurtwängler had a unique philosophy of music. He saw symphonic music as creations of nature that could only be realised subjectively into sound. Neville Cardus wrote in the Manchester Guardian in 1954 of Furtwängler's conducting style: "He did not regard the printed notes of the score as a final statement, but rather as so many symbols of an imaginative conception, ever changing and always to be felt and realised subjectively..."[159] And the conductor Henry Lewis: "I admire Furtwängler for his originality and honesty. He liberated himself from slavery to the score; he realized that notes printed in the score, are nothing but SYMBOLS. The score is neither the essence nor the spirit of the music. Furtwängler had this very rare and great gift of going beyond the printed score and showing what music really was."[160]

Many commentators and critics regard him as the greatest conductor in history.[161][162][163][164][165][166][167][168][169][170][171][172] In his book on the symphonies of Johannes Brahms, musicologist Walter Frisch writes that Furtwängler's recordings show him to be "the finest Brahms conductor of his generation, perhaps of all time", demonstrating "at once a greater attention to detail and to Brahms' markings than his contemporaries and at the same time a larger sense of rhythmic-temporal flow that is never deflected by the individual nuances. He has an ability not only to respect, but to make musical sense of, dynamic markings and the indications of crescendo and diminuendo[...]. What comes through amply... is the rare combination of a conductor who understands both sound and structure."[173] He notes Vladimir Ashkenazy who says that his sound "is never rough. It's very weighty but at the same time is never heavy. In his fortissimo you always feel every voice.... I have never heard so beautiful a fortissimo in an orchestra", and Daniel Barenboim says he "had a subtlety of tone color that was extremely rare. His sound was always 'rounded,' and incomparably more interesting than that of the great German conductors of his generation."

On the other hand, the critic David Hurwitz, a spokesman for modern literalism and precision, sharply criticizes what he terms "the Furtwängler wackos" who "will forgive him virtually any lapse, no matter how severe", and characterizes the conductor himself as "occasionally incandescent but criminally sloppy".[174] Unlike conductors such as Carlos Kleiber or Sergiu Celibidache, Furtwängler did not try to reach the perfection in details, and the number of rehearsals with him was small. He said:

I am told that the more you rehearse, the better you play. This is wrong. We often try to reduce the unforeseen to a controllable level, to prevent a sudden impulse that escapes our ability to control, yet also responds to an obscure desire. Let's allow improvisation to have its place and play its role. I think that the true interpreter is the one who improvises. We have mechanized the art of conducting to an awful degree, in the quest of perfection rather than of dream [...] As soon as rubato is obtained and calculated scientifically, it ceases to be true. Music making is something else than searching to achieve an accomplishment. But striving to attain it is beautiful. Some of Michelangelo's sculptures are perfect, others are just outlined and the latter ones move me more than the first perfect ones because here I find the essence of desire, of the wakening dream. That's what really moves me: fixing without freezing in cement, allowing chance its opportunity.[160]

His style is often contrasted with that of his contemporary Arturo Toscanini. He walked out of a Toscanini concert once, calling him "a mere time-beater!". Unlike Toscanini, Furtwängler sought a weighty, less rhythmically strict, more bass-oriented orchestral sound, with a more conspicuous use of tempo changes not indicated in the printed score.[175] Instead of perfection in details, Furtwängler was looking for the spiritual in art. Sergiu Celibidache explained,

Everybody was influenced at the time by Arturo Toscanini - it was easy to understand what he was trying to do: you didn't need any reference to spiritual dimension. There was a certain order in the way the music was presented. With Toscanini I never felt anything spiritual. With Furtwängler on the other hand, I understood that there I was confronted by something completely different: metaphysics, transcendence, the relationship between sounds and sonorities [...] Furtwängler was not only a musician, he was a creator [...] Furtwängler had the ear for it: not the physical ear, but the spiritual ear that captures these parallel movements.[176]

Furtwängler commemorated on a stamp for West Berlin, 1955

Furtwängler commemorated on a stamp for West Berlin, 1955Furtwängler's art of conducting is considered as the synthesis and the peak of the so-called "Germanic school of conducting".[177][178] This "school" was initiated by Richard Wagner. Unlike Mendelssohn's conducting style, which was "characterized by quick, even tempos and imbued with what many people regarded as model logic and precision [...], Wagner's way was broad, hyper-romantic and embraced the idea of tempo modulation".[179] Wagner considered an interpretation as a re-creation and put more emphasis on the phrase than on the measure.[180] The fact that the tempo was changing was not something new; Beethoven himself interpreted his own music with a lot of freedom. Beethoven wrote: "my tempi are valid only for the first bars, as feeling and expression must have their own tempo", and "why do they annoy me by asking for my tempi? Either they are good musicians and ought to know how to play my music, or they are bad musicians and in that case my indications would be of no avail".[181] Beethoven's disciples, such as Anton Schindler, testified that the composer varied the tempo when he conducted his works.[182] Wagner's tradition was followed by the first two permanent conductors of the Berlin Philharmonic.[183] Hans von Bülow highlighted more the unitary structure of symphonic works, while Arthur Nikisch stressed the magnificence of tone.[184] The styles of these two conductors were synthesized by Furtwängler.[184]

In Munich (1907-1909), Furtwängler studied with Felix Mottl, a disciple of Wagner.[185] He considered Arthur Nikisch as his model.[186] According to John Ardoin, Wagner's subjective style of conducting led to Furtwängler and Mendelssohn's objective style of conducting led to Toscanini.[183]

Furtwängler's art was deeply influenced by the great Jewish music theorist Heinrich Schenker with whom he worked between 1920 and Schenker's death in 1935. Schenker was the founder of Schenkerian analysis, which emphasized underlying long-range harmonic tensions and resolutions in a piece of music.[187][188] Furtwängler read Schenker's famous monograph on Beethoven's Ninth symphony in 1911, subsequently trying to find and read all his books.[189] Furtwängler met Schenker in 1920, and they continuously worked together on the repertoire which Furtwängler conducted. Schenker never secured an academic position in Austria and Germany, in spite of Furtwängler's efforts to support him.[190] Schenker depended on several patrons including Furtwängler. Furtwängler's second wife certified much later that Schenker had an immense influence on her husband.[191] Schenker considered Furtwängler as the greatest conductor in the world and as the "only conductor who truly understood Beethoven".[192]

Furtwängler's recordings are characterized by an "extraordinary sound wealth[184] ", special emphasis being placed on cellos, double basses,[184] percussion and woodwind instruments.[193] According to Furtwängler, he learned how to obtain this kind of sound from Arthur Nikisch. This richness of sound is partly due to his "vague" beat, often called a "fluid beat".[194] This fluid beat created slight gaps between the sounds made by the musicians, allowing listeners to distinguish all the instruments in the orchestra, even in tutti sections.[195] Vladimir Ashkenazy once said: "I never heard such beautiful fortissimi as Furtwängler's."[196] According to Yehudi Menuhin, Furtwängler's fluid beat was more difficult but superior than Toscanini's very precise beat.[197] Unlike Otto Klemperer, Furtwängler did not try to suppress emotion in performance, instead giving a hyper romantic aspect[198] to his interpretations. The emotional intensity of his World War II recordings is particularly famous. Conductor and pianist Christoph Eschenbach has said of Furtwängler that he was a "formidable magician, a man capable of setting an entire ensemble of musicians on fire, sending them into a state of ecstasy".[199] Furtwängler desired to retain an element of improvisation and of the unexpected in his concerts, each interpretation being conceived as a re-creation.[184] However, melodic line as well as the global unity were never lost with Furtwängler, even in the most dramatic interpretations, partly due to the influence of Heinrich Schenker and to the fact that Furtwängler was a composer and had studied composition during his whole life.[200]

Furtwängler was famous for his exceptional inarticulacy when speaking about music. His pupil Sergiu Celibidache remembered that the best he could say was, "Well, just listen" (to the music). Carl Brinitzer from the German BBC service tried to interview him, and thought he had an imbecile before him. A live recording of a rehearsal with a Stockholm orchestra documents hardly anything intelligible, only hums and mumbling. On the other hand, a collection of his essays, On Music, reveals deep thought.

InfluenceOne of Furtwängler's protégés was the pianist prodigy Karlrobert Kreiten who was killed by the Nazis in 1943 because he had criticized Hitler. He was an important influence on the pianist/conductor Daniel Barenboim (who decided to become a conductor when he was eight years old during a concert of the Passion Saint Matthew by Bach conducted by Furtwängler in 1950 in Buenos Aires ), of whom Furtwängler's widow, Elisabeth Furtwängler, said, "Er furtwänglert" ("He furtwänglers"). Barenboim has conducted a recording of Furtwängler's 2nd Symphony, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Other conductors known to speak admiringly of Furtwängler include Valery Gergiev, Claudio Abbado, Carlos Kleiber, Carlo Maria Giulini, Simon Rattle, Sergiu Celibidache, Otto Klemperer, Karl Böhm, Bruno Walter, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Christoph Eschenbach, Alexander Frey, Philippe Herreweghe, Eugen Jochum, Zubin Mehta, Ernest Ansermet, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, Bernard Haitink (who decided to become a conductor as a child and bedridden while listening to a Furtwängler concert on the radio during the second world war), Rafael Kubelík, Gustavo Dudamel, Jascha Horenstein (who had worked as an assistant to Furtwängler in Berlin during the 1920s), Kurt Masur and Christian Thielemann. For instance, Carlos Kleiber thought that "nobody could equal Furtwängler".[201] George Szell, whose precise musicianship was in many ways antithetical to Furtwängler's, always kept a picture of Furtwängler in his dressing room. Even Arturo Toscanini, usually regarded as Furtwängler's complete antithesis (and sharply critical of Furtwängler on political grounds), once said – when asked to name the World's greatest conductor apart from himself – "Furtwängler!". Herbert von Karajan, who in his early years was Furtwängler's rival, maintained throughout his life that Furtwängler was one of the great influences on his music making, even though his cool, objective, modern style had little in common with Furtwängler's white-hot Romanticism. Karajan said:

He certainly had an enormous influence on me [...] I remember that when I was Generalmusikdirektor in Aachen, a friend invited me to a concert that Furtwängler gave in Cologne [...] Furtwängler's performance of the Schumann's Fourth, which I didn't know at the time, opened up a new world for me. I was deeply impressed. I didn't want to forget this concert, so I immediately returned to Aachen.[202]

And Claudio Abbado said in an interview about his career (published in 2004):

Furtwängler is the greatest of all […]; Admittedly, one can sometimes dispute his choices, his options, but enthusiasm almost always prevails, especially in Beethoven. He is the musician who had the greatest influence on my artistic education.[203]

Furtwängler's performances of Beethoven, Wagner, Bruckner, and Brahms remain important reference points today, as do his interpretations of other works such as Haydn's 88th Symphony, Schubert's Ninth Symphony, and Schumann's Fourth Symphony. He was also a champion of modern music, notably the works of Paul Hindemith and Arnold Schoenberg[204] and conducted the World premiere of Sergei Prokofiev's Fifth Piano Concerto (with the composer at the piano) on 31 October 1932[205] as well as performances of Béla Bartók's Concerto for Orchestra.

The musicians who have expressed the highest opinion about Furtwängler are some of the most prominent ones of the 20th century such as Arnold Schönberg,[206] Paul Hindemith,[207] or Arthur Honegger.[208] Soloists such as Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau,[209][210] Yehudi Menuhin[211] Pablo Casals, Kirsten Flagstad, Claudio Arrau and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf[212] who have played music with almost all the major conductors of the 20th century have clearly declared upon several occasions that, for them, Furtwängler was the most important one. John Ardoin has reported the following discussion he has had with Maria Callas in August 1968 after having listened to Beethoven's Eight with the Cleveland orchestra conducted by George Szell:

"Well", she sighed, "you see what we have been reduced to. We are now in a time when a Szell is considered a master. How small he was next to Furtwängler." Reeling this disbelief -- not at her verdict, with which I agreed, but from the unvarnished acuteness of it -- I stammered, "But how do you know Furtwängler? You never sang with him." "How do you think?" she stared at me with equal disbelief. "He started his career after the war in Italy [in 1947]. I heard dozens of his concerts there. To me, he was Beethoven."[213]

Notable recordingsThere are a huge number of Furtwängler recordings currently available, mostly live. Many of these were made during World War II using experimental tape technology. After the war they were confiscated by the Soviet Union for decades, and have only recently become widely available, often on multiple legitimate and illegitimate labels. In spite of their limitations, the recordings from this era are widely admired by Furtwängler devotees.

This is only a small selection of some of Furtwängler's most famed recordings. For more information, see his discography and list of currently available recordings. The French Wilhelm Furtwängler Society also has a list of recommended recordings.

• Johann Sebastian Bach, St Matthew Passion (first half only), live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, 1952 (SWF)

• Bartók, Violin Concerto No. 2, studio recording with Yehudi Menuhin and with the Philharmonia Orchestra, 1953 (EMI)

• Beethoven, Third Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, December 1944 (Music and Arts, Preiser, Tahra)[214][215][216]

• Beethoven, Third Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, December 1952 (Tahra)

• Beethoven, Fifth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, June 1943 (Classica d'Oro, Deutsche Grammophon, Enterprise, Music and Arts, Opus Kura, Tahra)

• Beethoven, Fifth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, May 1954 (Tahra)

• Beethoven, Sixth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, March 1944 (Tahra)

• Beethoven, Seventh Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1943 (Classica d'Oro, Deutsche Grammophon, Music and Arts, Opus Kura)[217]

• Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, March 1942 with Tilla Briem, Elisabeth Höngen, Peter Anders, Rudolf Watzke, and the Bruno Kittel Choir (Classica d'Oro, Music and Arts, Opus Kura, Tahra, SWF)[218][219]

• Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, live performance at the 29 July 1951 re-opening of Bayreuther Festspiele (not to be confused with EMI's release) with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Elisabeth Höngen, Hans Hopf and Otto Edelmann. (Orfeo D'or, 2008).[220]

• Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, ostensibly a live performance at the 29 July 1951 re-opening of Bayreuther Festspiele but purported by the President of the Wilhelm Furtwängler Society of America to actually be dress rehearsal takes edited by EMI into one recording, all performed prior to the actual public performance. (EMI, 1955).[221]

• Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, live performance at the 1954 Lucerne Festival with the London Philharmonia, Lucerne Festival Choir, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Elsa Cavelti, Ernst Haefliger and Otto Edelmann (Music and Arts, Tahra).[222]

• Beethoven, Violin Concerto, studio recording with Yehudi Menuhin and with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, 1947 (Testament)

• Beethoven, Piano Concerto No. 5, studio recording with Edwin Fischer and with the Philharmonia Orchestra, 1951 (Naxos)

• Beethoven, Fidelio, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic with Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Kirsten Flagstad, Anton Dermota, Julius Patzak, Paul Schoeffler, Josef Greindl, and Hans Braun, August 1950 (Opus Kura)

• Beethoven, Fidelio, both live and studio recordings, with Martha Mödl, his preferred soprano, in the title role, and Wolfgang Windgassen, Otto Edelmann, Gottlob Frick, Sena Jurinac, Rudolf Schock, Alfred Poell, Alwin Hendriks, Franz Bierbach, and the Vienna Philharmonic.

• Brahms, First Symphony, live performance with the North German Radio Symphony Orchestra, Hamburg, October 1951 (Music and Arts, Tahra).[223]

• Brahms, Second Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, January 1945 (Deutsche Grammophon, Music and Arts)

• Brahms, Third Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, December 1949 (EMI).[224]

• Brahms, Fourth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, December 1943 (Tahra, SWF)

• Brahms, Fourth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1948 (EMI)

• Brahms, Violin Concerto, studio recording with Yehudi Menuhin and with the Lucerne Festival Orchestra, 1949 (Tahra, Naxos)

• Brahms, Piano Concerto No. 2, live performance with Edwin Fischer and with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1942 (Testament)

• Bruckner, Fourth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1941 (WFCJ)

• Bruckner, Fifth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1942 (Classica d'Oro, Deutsche Grammophon, Music and Arts, Testament).[225]

• Bruckner, Sixth Symphony (the first movement is missing), live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, November 1943 (Music and Arts)

• Bruckner, Seventh Symphony (adagio only), live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, April 1942 (Tahra).[226]

• Bruckner, Eighth Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, October 1944 (Deutsche Grammophon, Music and Arts)

• Bruckner, Ninth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, October 1944 (Deutsche Grammophon)

• Franck, Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, 1945 (SWF)

• Furtwängler, Second Symphony, live performance with the Vienna Philharmonic, February 1953 (Orfeo)

• Gluck, Alceste Ouverture, studio recording with the Vienna Philharmonic, 1954 (SWF)

• Haendel, Concerto Grosso Opus 6 No. 10, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, February 1944 (Melodiya)

• Haendel, Concerto Grosso Opus 6 No. 10, live performance with the Teatro Colón Orchester, 1950 (Disques Refrain)

• Haydn, 88th Symphony, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, 5 December 1951 (Deutsche Grammophon)

• Hindemith, Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, 16 September 1947 (Deutsche Grammophon, Urania)

• Mahler, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, live performance with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and the Vienna Philharmonic, 1951 (Orfeo)

• Mahler, Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen, studio recording with Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and the Philharmonia Orchestra, 1952 (Naxos, EMI)

• Mendelssohn, Violin Concerto, studio recording with Yehudi Menuhin and with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1952 (Naxos, EMI)

• Mozart, Don Giovanni, the 1950, 1953 and 1954 Salzburg Festival recordings (in live performance). These have been made available on several labels, but mostly EMI. A videotaped performance of Don Giovanni is also available, featuring Cesare Siepi, Otto Edelmann, Lisa Della Casa, Elisabeth Grümmer, and Anton Dermota.

• Mozart, Die Zauberflöte, a live performance from 27 August 1949, featuring Walther Ludwig, Irmgard Seefried, Wilma Lipp, Gertrud Grob-Prandl, Ernst Haefliger, Hermann Uhde, and Josef Greindl.

• Schubert, Eighth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, December 1944 (SWF)

• Schubert. Ninth Symphony, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1951 (Deutsche Grammophon). The first movement is a supreme example of Furtwaengler's style. Note the sharp accelerandi at the end of the introduction and the middle of the recapitulation.

• Schubert, Ninth Symphony, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, 1942 (Deutsche Grammophon, Magic Master, Music and Arts, Opus Kura)

• Schubert, Die Zauberharfe Overture, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, September 1953 (Deutsche Grammophon)

• Schumann, Fourth Symphony, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, Deutsche Grammophon, May 1953 (Deutsche Grammophon).[227]

• Sibelius, En saga, live performance with the Berlin Philharmonic, February 1943 (SWF)

• Tchaikovsky, Fourth Symphony, studio recording with the Vienna Philharmonic, 1951 (Tahra)

• Tchaikovsky, Sixth Symphony Pathétique, studio recording with the Berlin Philharmonic, HMV, 1938 (EMI, Naxos).[228]

• Wagner, Tristan und Isolde, studio recording with Flagstad, HMV, June 1952 (EMI, Naxos).[229]

• Wagner, Der Ring des Nibelungen, 1950 (live recording from La Scala in Milan with Kirsten Flagstad)

• Wagner, Der Ring des Nibelungen with Wolfgang Windgassen, Ludwig Suthaus, and Martha Mödl, 1953 (EMI) (recorded live in the RAI (Radiotelevisione Italiana) studios).

• Wagner, Die Walküre, his last recording in 1954. EMI planned to record "Der Ring des Nibelungen" in the studio under Furtwängler, but he only finished this work shortly before his death. The cast includes Martha Mödl (Brünnhilde), Leonie Rysanek (Sieglinde), Ludwig Suthaus (Siegmund), Gottlob Frick (Hunding), and Ferdinand Frantz (Wotan).

Notable premieres• Bartók, First Piano Concerto, the composer as soloist, Theater Orchestra, Frankfurt, 1 July 1927

• Schoenberg, Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Berlin, 2 December 1928

• Prokofiev: Piano Concerto No. 5, the composer as soloist, Berlin Philharmonic, 31 October 1932

• Hindemith, suite from Mathis der Maler, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Berlin, 11 March 1934

• Richard Strauss, Four Last Songs, Kirsten Flagstad as soloist, Philharmonia Orchestra, London, 22 May 1950

Notable compositions

Orchestral

Early works• Overture in E♭ Major, Op. 3 (1899)

• Symphony in D major (1st movement: Allegro) (1902)

• Symphony in B minor (Largo movement) (1908; the principal theme of this work was used as the leading theme of the 1st movement of the Symphony No. 1, in the same key)

Later works• Symphonic Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1937, rev. 1952-54)

• Symphony No. 1 in B minor (1941)

• Symphony No. 2 in E minor (1947)

• Symphony No. 3 in C♯ minor (1954)

Chamber music• Piano Quintet (for two violins, viola, cello, and piano) in C major (1935)

• Violin Sonata No. 1 in D minor (1935)

• Violin Sonata No. 2 in D major (1939)

Choral(all early works)

• Schwindet ihr dunklen Wölbungen droben (Chorus of Spirits, from Goethe's Faust) (1901–1902)

• Religöser Hymnus (1903)

• Te Deum for Choir and Orchestra (1902–1906) (rev. 1909) (first performed 1910)

In popular culture• British playwright Ronald Harwood's play Taking Sides (1995), set in 1946 in the American zone of occupied Berlin, is about U.S. accusations against Furtwängler of having served the Nazi regime. In 2001 the play was made into a motion picture directed by István Szabó and starring Harvey Keitel and featuring Stellan Skarsgård in the role of Furtwängler.[230]

References

Informational notes1. Philipp Furtwängler (*1869) couldn't be Wilhelm Furtwängler's (*1886) brother, because Wilhelm was the first child of his parents and his brother Philipp a mathematician.

Citations1. Cowan, Rob (14 March 2012). "Furtwängler – Man and Myth". Gramophone. Retrieved 10 April2012.

2. Cairns, David (1980). "Wilhelm Furtwängler" in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. London: Macmillan.

3. Geissmar, Berta (1944). The Baton and the Jackboot: Recollections of Musical Life. London and Edinburgh: Morrison and Gibb ltd. p. 12.

4. Geissmar, p. 15

5. Geissmar, pp. 20-5 and 143-7

6. Geissmar, p. 23

7. Geissmar, pp. 20-5 and 30

8. Riess, Curt (1953). Furtwängler, Musik und Politik. Berne: Scherz. p. 89.

9. Geissmar, pp. 66–67.

10. Roncigli, Audrey (2009). Le cas Furtwängler. Paris: Imago. p. 37.

11. Prieberg, Fred K. (1991). Trial of Strength: Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Third Reich. Quartet Books. pp. 57–60.

12. Prieberg, p. 44.

13. Prieberg, p. 340.

14. Prieberg, p. 55.

15. Prieberg, p. 74.

16. Ardoin, John (1994). The Furtwängler Record. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-931340-69-7.

17. Schönzeler, Hans-Hubert (1990). Furtwängler. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7156-2313-8.

18. Roncigli, p. 46.

19. Prieberg, p. 319.

20. Roncigli, p. 109.

21. Prieberg, p. 94.

22. Galo, Gary A., Review of The Furtwängler Record by John Ardoin (December 1995). Notes (2nd Ser.), 52 (2): pp. 483–485.

23. Ardoin, p. 47

24. Prieberg

25. Prieberg, p. 220.

26. Prieberg, Chapter 2.

27. Riess, p. 113.

28. Prieberg, Fred K. (1991). Trial of Strength: Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Third Reich. Quartet Books. p. 187., the picture is reproduced in the book p. 187.

29. Prieberg, p. 100.

30. Ardoin, p. 50.

31. Geissmar, p.86.

32. Roncigli, p. 45.

33. Riess, p. 109.

34. Geissmar, pp 81-2

35. Geissmar, p. 82.

36. Riess, p. 110.

37. " L'atelier du Maître ", article by Philippe Jacquard on the web site of the french Wilhelm Furtwängler society: read on line.

38. Prieberg, p. 138.

39. Spotts, Frederick (2003). Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. Overlook Books. p. 291.

40. Roncigli, p. 48.

41. Geissmar, p. 144.

42. Riess, p. 139.

43. Geissmar, p. 132.

44. Riess, p. 141.

45. Geissmar, p. 159.

46. Riess, p. 142.

47. Riess, p. 144.

48. Roncigli, p. 52.

49. Elisabeth Furtwängler, Pour Wilhelm, Paris, L'Archipel, 2004, p. 51 and p. 128.

50. Klaus Lang, Celibidache et Furtwängler [" Celibidache und Furtwängler "], Paris, Buchet/Chastel, 2012, p. 55.

51. Prieberg, chapter 5.

52. Riess, p. 143.

53. Prieberg, p. 172.

54. Riess, p. 145.

55. Prieberg, p. 173.

56. Roncigli, p. 51.

57. Spotts, p. 293

58. Riess, p. 151.

59. Prieberg, p. 150.

60. Roncigli, p. 253.

61. Prieberg, p. 177.

62. Riess, p. 152.

63. Schönzeler, p.74.

64. HSchönzeler, p. 74.

65. Riess, p. 153.

66. Schönzeler, p. 75.

67. Wilhelm Furtwängler (trad. Ursula Wetzel, Jean-Jacques Rapin, préf. Pierre Brunel), Carnets 1924-1954 : suivis d’Écrits fragmentaires, Genève, éditions Georg, 1995, p. 39.

68. Wilhelm Furtwängler (trad. Ursula Wetzel, Jean-Jacques Rapin, préf. Pierre Brunel), Carnets 1924-1954 : suivis d’Écrits fragmentaires, Genève, éditions Georg, 1995, p. 11.

69. Prieberg, p.188.

70. Roncigli, p. 104.

71. Prieberg, p.191.

72. Riess, p. 155.

73. Curt Riess, Furtwängler, Musik und Politik, Berne, Scherz, 1953, p. 156.

74. Riess, p. 157.

75. ASIN 0761501371

76. Riess, pp. 157-159.

77. "Music: Partisans on the Podium". Time. 25 April 1949.

78. Roncigli, p. 56.

79. Roncigli, p. 254.

80. Schönzeler, Hans-Hubert (1990). Furtwängler. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7156-2313-8.

81. Vaget, Hans Rudolf (2006). Seelenzauber: Thomas Mann und die Musik. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer. p. 270.

82. Roncigli, p. 53.

83. Roncigli, p. 54.

84. Curt Riess, Furtwängler, Musik und Politik, Berne, Scherz, 1953, p. 165.

85. Schönzeler, p. 81.

86. Curt Riess, Furtwängler, Musik und Politik, Berne, Scherz, 1953, p. 166.

87. Riess, pp. 168-169.

88. Prieberg, p.221.

89. Roncigli, p.102.

90. Prieberg, p. 239.

91. Prieberg, p. 241.

92. Prieberg, p. 242.

93. Prieberg, p. 244.

94. Geissmar, p. 352.

95. Schönzeler, p. 89.

96. Roncigli, p. 59.

97. Prieberg, p. 231.

98. Riess, p. 174.

99. Riess, p. 176.

100. Riess, p. 175.

101. Prieberg, p. 235.

102. Prieberg, p. 236.

103. Roncigli, p. 57.

104. Spotts, p. 295

105. Roncigli, p. 102.

106. Prieberg, p. 272.

107. Hürlimann, Martin (1955). Wilhelm Furtwängler im Urteil seiner Zeit. Atlantis Verlag. p. 215.

108. Roncigli, p. 60.

109. See David Cairns, ibid

110. Roncigli, p.60.

111. Riess, p. 185.

112. Prieberg, p. 285.

113. Roncigli, p.115.

114. Prieberg, p. 291.

115. Roncigli, p.75.

116. Roncigli, p.64.

117. Geissmar

118. Shirakawa, Sam, chap. 15

119. Prieberg, p. 320.

120. Riess, p. 191.

121. Prieberg, p. 306.

122. Joseph Goebbels, Reden 1932–1939, hrsg. von Helmut Heiber, Düsseldorf, Droste Verlag, 1972, p. 282.

123. Wilfried von Oven, Finale furioso, Mit Goebbels zum Ende. Tübingen, Grabert Verlag, 1974, p. 268.

124. Spotts, p. 87

125. Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (1970) Macmillan pp 548.

126. Prieberg, p. 317.

127. Roncigli, p. 171.

128. Roncigli, p.174.

129. Schönzeler, p. 93.

130. Schönzeler, p. 94.

131. Bernard D. Sherman. (1997) [1999]. "Brahms: The Symphonies/Charles Mackerras". Fanfare. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

132. Roncigli, p. 76.

133. Roger Smithson, article "The Years of Silence (1945-1947)", p. 9 on the website of the French Wilhelm Furtwängler society: [1]

134. Riess, Curt (1953). Furtwängler, Musik und Politik. Berne: Scherz. p. 16.

135. Riess, Curt (1953). Furtwängler, Musik und Politik. Berne: Scherz. p. 17.

136. Roncigli, p. 77.

137. Roncigli, p. 79.

138. Roncigli, p. 78.

139. Roncigli, p. 131.

140. Roger Smithson, article "The Years of Silence (1945-1947)", p. 7 on the website of the French Wilhelm Furtwängler society: [2]

141. Prieberg, p. 226.

142. Roger Smithson (1997). "Furtwängler's Silent Years: 1945–47" (.RTF). Société Wilhelm Furtwängler. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

143. Monod, David (2005). Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans, 1945–1953. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-8078-2944-8.

144. Riess, Curt (1953). Furtwängler, Musik und Politik. Berne: Scherz. p. 188.

145. Klaus Lang, Celibidache et Furtwängler [" Celibidache et Furtwängler "], Paris, Buchet/Chastel, 2012, p. 79.

146. Klaus Lang, Celibidache et Furtwängler [" Celibidache et Furtwängler "], Paris, Buchet/Chastel, 2012, p. 80.

147. Roncigli, Audrey (2009). Le cas Furtwängler. Paris: Imago. pp. 171–194.

148. Roncigli, Audrey (2009). Le cas Furtwängler. Paris: Imago. p. 103.

149. Prieberg, Fred K. (1991). Trial of Strength: Wilhelm Furtwängler and the Third Reich. Quartet Books. p. 344.

150. Roncigli, Audrey (2009). Le cas Furtwängler. Paris: Imago. p. 133.

151. Roncigli, p. 133.

152. "In Memoriam Furtwängler", Tahra 2004.

153. Quoted from John Ardoin's The Furtwängler Record

154. Vaget (2006). Seelenzauber. pp. 483–84.

155. Ardoin, p.58.

156. Taubman, Howard (6 January 1949). "Musicians' Ban on Furtwaengler Ends His Chicago Contract for '49". The New York Times. reprinted in McLanathan, Richard B K; Gene Brown (1978). The Arts. New York: Arno Press. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-405-11153-2.

157. Klaus Lang, Celibidache et Furtwängler [" Celibidache und Furtwängler "], Paris, Buchet/Chastel, 2012, p. 137.

158. Yehudi Menuhin, Le violon de la paix, Paris, éditions alternatives, 2000, p. 154.

159. Martin Kettle (26 November 2004). "Second coming". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 21 July2007.

160. Wilhelm Furtwängler, CD Wilhelm Furtwängler in Memoriam FURT 1090–1093, Tahra, 2004, p. 54.

161. "Arguably the greatest conductor of all time", "The Furtwangler Legacy on BBC radio, November 2004". Archived from the original on 30 May 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2012..

162. "The greatest conductor of all time", "Furtwangler's love, 2004"..

163. "The most influential and important orchestral conductor of the recorded era", Kettle, Martin (26 November 2004). "Second coming". The Guardian..

164. "Amazing, spur-of-the-moment inspirational intensity, probably unsurpassed by any other conductor before or since", "Sinfini Music, Top 20 conductors, November 2012"..

165. "Wilhelm Furtwängler is widely considered the one of the greatest—if not the very greatest—conductors of the twentieth century", "Ten Perfect Orchestral Recordings on The New Yorker, article by David Denby, May 1, 2012". The New Yorker. May 2012..

166. "Maybe the greatest conductor in history", Patrick Szersnovicz, Le Monde de la musique, December 2004, p. 62–67.

167. "Maybe the greatest conductor in history, probably the greatest Beethovenian", "L'orchestre des rites et des dieux", editor: Autrement, series mutation, volume 99, 1994, p. 206.

168. "Why was Wilhelm Furtwängler the greatest conductor in history?" Critic Joachim Kaiser, course in German available on the web site of the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper.

169. "Wilhelm Furtwängler Biography". Naxos. Retrieved 21 July 2007.

170. "Many saw and see him as the greatest conductor of the 20th century", Von Stefan Dosch "Als mitten im Weltkrieg große Musik entstand". Augsburger Allgemeine. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

171. "An artist frequently regarded as the most important conductor in the history of phonography, or even of all time", Maciej Chiżyński "Wilhelm Furtwängler le géant, enregistrements radio à Berlin 1939-1945". ResMusica. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

172. "La tradizione di Furtwängler". HUFFPOST. Retrieved 12 April 2021., "probably the greatest conductor of all time" ("probabilmente è il più grande direttore d’orchestra di tutti i tempi"), Giovanni Giammarino.

173. Frisch, Walter (2003). Brahms: The Four Symphonies. Yale University Press. pp. 183–185. ISBN 978-0-300-09965-2.

174. "Historical Gems: Furtwängler RIAS Recordings from Audite - Classics Today".

175. The difference is sometimes mis-characterized by the terms "objective" and "subjective", but Furtwängler's tempo inflections were often planned and reflected his studies with the harmonic theorist Heinrich Schenker from 1920 to 1935.

176. Sergiu Celibidache, CD Wilhelm Furtwängler in Memoriam FURT 1090–1093, Tahra, 2004, p. 57.

177. Harold Schönberg, The great conductors, Simon and Schuster, 1967.

178. Ardoin

179. Ardoin, p.18.

180. Ardoin, pp.19–20.

181. Beethoven, CD Furtwängler, Beethoven's Choral Symphony, Tahra FURT 1101–1104, p. 28.

182. Ardoin, p. 21.

183. Ardoin, p. 22.

184. (in French) Patrick Szersnovicz, Le Monde de la musique, December 2004, p. 62–67.

185. Ardoin, p. 25.

186. Elisabeth Furtwängler, Pour Wilhelm, Paris, 2004, p. 32.

187. SchenkerGUIDE By Tom Pankhurst, p. 5 ff

188. Schenker Documents Online.

189. Sami Habra, CD Furtwängler, Beethoven's Choral Symphony, Tahra FURT 1101–1104, p. 18.

190. (in French) Biography of Schenker on the Internet site of Luciane Beduschi and Nicolas Meeùs.

191. Elisabeth Furtwängler, Pour Wilhelm, Paris, 2004, p.54.

192. CD Furtwängler, Beethoven's Choral Symphony, Tahra FURT 1101–1104, p. 19.

193. David Cairns, CD Beethoven's 5th and 6th Symphonies, 427 775-2, DG, 1989, p. 16.

194. Ardoin, p. 12.

195. Patrick Szersnovicz, Le Monde de la musique, December 2004, p. 66

196. CD Wilhelm Furtwängler, his legendary post-war recordings, Tahra, harmonia mundi distribution, FURT 1054/1057, p. 15.

197. Yehudi Menuhin, DVD The Art of Conducting - Great Conductors of the Past, Elektra/Wea, 2002.

198. Wilhelm Furtwängler, Carnets 1924–1954, 1995, p. 103.

199. Christoph Eschenbach Own Words on His Life

200. Elisabeth Furtwängler, Pour Wilhelm, 2004, p. 55.

201. "Carlos Kleiber, un don et une malédiction". Le Huffington Post. 17 July 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

202. Herbert von Karajan, CD Wilhelm Furtwängler in Memoriam FURT 1090–1093, Tahra, 2004, p. 57.

203. 'La symphonie des chefs, Robert Parienté, Éditions de La Martinière, Paris, 2004, p. 249-259.

204. Michael H Kater The Twisted Muse, p.198

205. Daniel Jaffé Sergey Prokofiev, p.128 (London: Phaidon, 1998)

206. Gérard Gefen, Furtwängler, une Biographie par le disque, Belfond, 1986, p. 51.

207. Leins Hermann, Diener der Musik, herausgegeben von Martin Müller und Wolfgang Mertz, Rainer Wunderlich Verlag, 1965, p. 180–187.

208. About Furtwängler's second symphony, Honneger wrote: "the man who can write a score so rich as this is not to be argued about. He is of the race of great musicians". CD Wilhelm Furtwängler The Legend, 9 08119 2, EMI, 2011, p. 7.

209. Fischer-Dieskau, Dietrich (2009). Jupiter und ich: Begegnungen mit Furtwängler. Berlin: Berlin University Press. ISBN 978-3-940432-66-7.

210. Kettle, Martin (20 May 2005). "It is the start of the final episode". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

211. Menuhin, Yehudi (2009). La légende du violon. Flammarion. p. 242.

212. DVD The Art of Conducting - Great Conductors of the Past, Elektra/Wea, 2002.

213. Ardoin, p.12.

214. About this recording, often considered as one of the most important ones of the 20th century, John Ardoin wrote: "The magnificent 1944 performance with the Vienna Philharmonic [is] an authenticated performance that is not only Furtwängler's noblest and most compelling Eroica, but one unrivalled on disc", Ardoin, p.120.

215. "A performance of prodigious classicism, it presents us with figures that seem to us to be made of stone by virtue of their nobility and of fire because of their compelling urgency, but which, on the wings of a scherzo at the pace of a march, suddently releases the infinite - placed on record", André Tubeuf, EMI C 051-63332, 1969.

216. "A guide to the best recordings of Beethoven's Symphony No 3, 'Eroica'". Gramophone. Retrieved 7 May 2019., "In the high peaks of the Marcia funebre and in the finale, the 1944 Vienna performance remains unsurpassed [...] No conductor articulates the drama of the Eroica – human and historical, individual and universal – more powerfully or eloquently than Furtwängler. Of his 11 extant recordings, it is this 1944 Vienna account, closely followed by the 1950 Berlin version, which most merits pride of place".

217. Harry Halbreich wrote in his analysis of this performance: "Does the second movement remain an Allegretto under Furtwängler's baton? Many critics have raised this question, troubled by the spaciousness even more than in Berlin than in Vienna [in 1950]. And yet, why hesitate? From the first bars, this perfection overrules us - beyond doubt, this is humanely, organically the right tempo and it would be completely insensitive and unmusical to argue otherwise [...] Who could describe the incredible beauty of phrasing of the song of violas and cellos [...] the sublime expressiveness of the violins? [...] The second theme on its reappearance seems still more moving and expressive [...] This Finale was always one of Furtwängler's great warhorses and undoubtedly the summit of this interpretation [...] Furtwängler relives his unbelievable performance of the end of the Fifth Symphonyin June 1943, four months before, launching into a break-taking acceleration without the unleashed forces ever escaping the control of the brilliant leader. "I am the Bacchus who distils the delicious nectar for mankind, and brings them to divine frenzy of the spirit": thus Beethoven explained himself. But it takes a demiurge like Furtwängler, that autumn day in 1943, to bring that frenzy to life in sound!", Harry Halbreich, CD Furtwängler conducts Beethoven, SWF 941, 1994, p.11.

218. Harry Halbreich wrote in his analysis of this performance that, for the first movement, "nobody has ever approached Furtwängler in the evocation of this terrifying release of cosmic forces" and about the Adagio: "in its superhuman spaciousness, which seems to seek to renounce human time and to align itself with that of creation, was not this Adagio the highest achievement of Wilhelm Furtwängler's art? Certainly no other conductor allowed himself such interpretative scope, and none put himself so much at risk. Yet on actual hearing the tempi prove so right, so natural lending themselves so perfectly to the whole presentation of the musical thought that one can hardly imagine anything different". For the Finale, he says: "from bar 321 Furtwängler imperiously asserts his presence with a gradual allargando building up to the colossal fortissimo of bar 330 followed by a timeless pause, a divine vision in which Beethoven, thanks to an interpreter worthy of him, equals the stature of the Michelangelo of the Sistine Chapel", Harry Halbreich, CD Beethoven, Ninth Symphony, SWF 891R, 2001, p.8–10.

219. "The 1942 performance in Berlin is one of the most convincing proofs of Furtwängler's rebellion during Germany's tragic era, while the nazis tried in vain to bury the great German musical heritage by using it for their sinister ends. Furtwängler fought for it and strived to save it from their cluthes", Sami Habra, CD Furtwängler, Beethoven's Choral Symphony, Tahra FURT 1101–1104, p. 19.

220. Sami Habra wrote regarding this very famous concert: "Yet, after the war, he had to prove to the World that German musical Art had indeed survived that fateful period as well as some attempts by the Allies to ignore or undermine German culture. The whole musical world retained its breath while Beethoven was universally re-born when Furtwängler conducted the Ninth for the re-opening of Bayreuth in 1951", Sami Habra, CD Furtwängler, Beethoven's Choral Symphony, Tahra FURT 1101–1104, p. 19.

221. Kees A. Schouhamer Immink (2007). "Shannon, Beethoven, and the Compact Disc". IEEE Information Theory Newsletter: 42–46. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

222. Sami Habra said: "The Lucerne 1954 concert, Furtwängler's last performance of the Ninth, allowed the listener an even deeper insight into the great conductor's art, the most important impression being that of abyssal depths that permeate this Swan song: no doubt Furtwängler sensed his end was near...", Sami Habra, CD Furtwängler, Beethoven's Choral Symphony, Tahra FURT 1101–1104, p. 19.

223. This Brahms 1st turned out to be Furtwängler's best version [...] More than ever, the broad opening, with the hammering of Friedrich Weber on the timpani and the soaring strings of that magnificent ensemble, impress the listener. The special quality of the string section, miraculously dense and transparent at the same time, permeates the whole work. The four great fortissimi of the first movement have an irresistible "élan", the long lyrical phrases of the second movement enchant the listener with their intensity. The third movement is Furtwängler at his most feverish here, and full of serenity is reached only after the repeated trumpet calls [...] The 4th movement is played with unmistakable grandeur and solemnity, as indeed the whole work is. While keeping Brahms' personality in mind, Furtwängler nevertheless brings out Beethoven's influence on Brahms [...] No wonder the French critics bestowed upon this recording the "Diapason d'Or of the century"....", Sami Habra, CD Wilhelm Furtwängler, his legendary post-war recordings, Tahra, harmonia mundi distribution, FURT 1054/1057, p. 19.

224. "Furtwängler's interpretations of Brahms go beyond the merely "composed" notation and realise the vision of the organic form that hovered before Brahms but can no longer be attained. Herein lies the explanation of the flawless formal architecture of his interpretations as well as the psychical compulsion of their musical performance that never becomes lost in detail but, to the contrary, always keeps the work as a whole in view. In this recording, notwithstanding his traditional interpretative style Furtwängler, unlike many a younger composer, lays more stress on the characteristics beyond the classical model symphony that herald the new trend: "Spiritual life" which Furtwängler traces and creates anew in each work - in this symphony, energetic and vigorous though it is, spiritual life is not concentrated on the dualism of the themes, the dramatic development and the intensity of the finale, but above all on the variety of tone-colours which are here formative energy that puts a constantly changing complexion on the scarcely modulated themes and motifs and becomes the favourite means of musical expression.", Sigurd Schimpf, EMI C 049-01 146.

225. "The interpretation is typically manic: very fast, and very slow. It lurches about impulsively and has thrilling moments–but also some pretty distressing examples of shoddy ensemble, particularly in the scherzo and finale. It was all too seldom that Furtwängler managed to keep his band together to allow him to time his climaxes optimally. A classic case of "overshoot" occurs at the end of the first movement, which sounds terribly rushed. The Adagio, though, is magnificent...", "Bruckner: Symphony No. 5/Furtwängler". classicstoday.com. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

226. "Furtwängler has always been Bruckner's greatest exponent [...] Again, the tragic element and grandeur are unequalled here. This is a "desert island" recording, fortunately restored for music lovers of this World to cherish all their life", Sami Habra, CD Furtwängler " revisited ", FURT 1099, Tahra, 2005, p.10.

227. "Schumann's Fourth [has] long [been regarded] as the recording of the century (along with the HMV Tristan) [...] Before the boisterous last movement starts, there is the famous transitional passage in which Furtwängler builds up the most impressive crescendo ever heard. This crescendo is referred to by Conservatoire teachers and conductors as being the very perfection, in spite of its infeasibility. Celibidache and Karajan have tried to imitate Furtwängler in this part on some occasions, but both conductors run out of breath towards the middle of the crescendo. This Furtwängler performance has yet to be equalled...", Sami Habra, CD Furtwängler " revisited ", FURT 1099, Tahra, 2005, p.11.

228. "According to Friedland Wagner, this 1938 performance of the "Pathetique" by Furtwängler was so overwhelming that Toscanini, in his house at Riverdale, played this recording again and again to his guests on a memorable day, pointing out with enthusiasm all its fine points [...] We can safely say that no one has probed as deeply as Furtwängler into the abyss of the tragic contents and pessimistic forebodings of the "Pathetique" [...] The last movement would probably have contained a glimmer of hope, had it not been for the fateful events that were to plunge the World into its darkest hours. Many observers have asserted that Furtwängler had foreseen what was to happen", Sami Habra, CD Furtwängler " revisited ", FURT 1099, Tahra, 2005, p.9.

229. "Produced in 1952, this recording, now reissued, has long been something of a landmark in recent history - rightly so, for its importance and its uniqueness are unquestionable [...] Wilhelm Furtwängler's architectural greatness is communicated so directly, so forcefully from the very first bar that one immediately forgets the small imperfections of the mono recording [...] The most striking thing is certainly the cogency of this interpretation. Nowhere are there hiatuses, breaks in the music's flow. Furtwängler, though far from being a perfectionist in individual detail, invariably seems to see the entire conception before him, so grippingly does he span the work's long arches, so magnificently does he weld together the various components. [...] His feeling for form is so compelling in its certainty that one does not stop to consider for a moment that it is not the only way of interpreting a particular phrase or sequence [...] The idea of Furtwängler seeking effect from a series of 'purple passages' is unthinkable; and yet the great emotional crescendi, the great climaxes, have a dramatic power scarcely matched elsewhere", Gerhard Brunner, CD Tristan und Isolde, EMI CDS 7 47322 8, p. 20.

230. Taking Sides (2001) at IMDb

Bibliography• Cairns, David "Wilhelm Furtwängler" in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians London: Macmillan, 1980.

• Frisch, Walter Brahms: The Four Symphonies New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003 ISBN 978-0-300-09965-2

• Geissmar, Berta The Baton and the Jackboot: Recollections of Musical Life, Morrison and Gibb ltd., 1944.

• Kater, Michael H. The Twisted Muse: Musicians and Their Music in the Third Reich Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

• Spotts, Frederic Hitler and the Power of Aesthetics. London: Hutchinson, 2002. ISBN 978-0-09-179394-4

• Shirakawa, Sam H. The Devil's Music Master: The controversial life and career of Wilhelm Furtwängler Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992 ISBN 978-0-19-506508-4

Further reading

• Ardoin John, The Furtwängler Record. Portland: Amadeus press,1994. ISBN 978-0-931340-69-7.

• Furtwängler, Wilhelm. Notebooks 1924–1954. Edited by Michael Tanner. Translated by Shaun Whiteside. London: Quartet Books, 1989. ISBN 978-0-7043-0220-4.

• Pirie Peter, Furtwängler and the Art of Conducting. London, Duckworth, 1980, ISBN 978-0-7156-1486-0

External links• Wilhelm Furtwängler at AllMusic

• Newspaper clippings about Wilhelm Furtwängler in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW