by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/26/21

Kalidasa

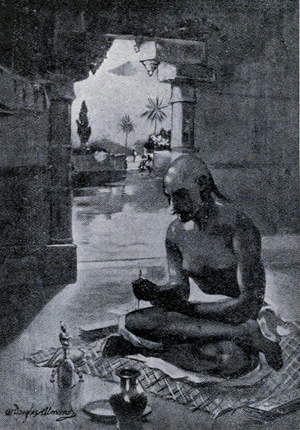

A 20th century artist's impression of Kālidāsa composing the Meghadūta

Occupation: Poet, Dramatist

Language: Sanskrit, Prakrit

Period: c. 4th–5th century CE

Genre: Sanskrit drama, Classical literature

Subject: Epic poetry, Puranas

Notable works: Kumārasambhavam, Abhijñānaśākuntalam, Raghuvaṃśa, Meghadūta, Vikramōrvaśīyam

Kālidāsa (Devanagari: कालिदास; fl. 4th–5th century CE) was a Classical Sanskrit author who is often considered ancient India's greatest playwright and dramatist. His plays and poetry are primarily based on the Vedas, the Rāmāyaṇa, the Mahābhārata and the Purāṇas.[1] His surviving works consist of three plays, two epic poems and two shorter poems.

Much about his life is unknown except what can be inferred from his poetry and plays.[2] His works cannot be dated with precision, but they were most likely authored before the 5th century CE.

Early life

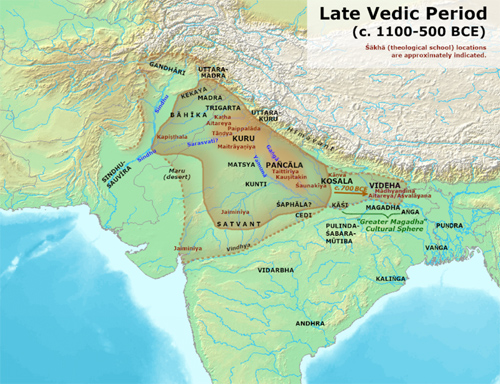

Scholars have speculated that Kālidāsa may have lived near the Himalayas, in the vicinity of Ujjain, and in Kalinga. This hypothesis is based on Kālidāsa's detailed description of the Himalayas in his Kumārasambhava, the display of his love for Ujjain in Meghadūta, and his highly eulogistic descriptions of Kalingan emperor Hemāngada in Raghuvaṃśa (sixth sarga).

Lakshmi Dhar Kalla (1891–1953), a Sanskrit scholar and a Kashmiri Pandit, wrote a book titled The birth-place of Kalidasa (1926), which tries to trace the birthplace of Kālidāsa based on his writings. He concluded that Kālidāsa was born in Kashmir, but moved southwards, and sought the patronage of local rulers to prosper. The evidence cited by him from Kālidāsa's writings includes:[3][4][5]

• Description of flora and fauna that is found in Kashmir, but not Ujjain or Kalinga: the saffron plant, the deodar trees, musk deer etc.

• Description of geographical features common to Kashmir, such as tarns and glades

• Mention of some sites of minor importance that, according to Kalla, can be identified with places in Kashmir. These sites are not very famous outside Kashmir, and therefore, could not have been known to someone not in close touch with Kashmir.

• Reference to certain legends of Kashmiri origin, such as that of the Nikumbha (mentioned in the Kashmiri text Nīlamata Purāṇa); mention (in Shakuntala) of the legend about Kashmir being created from a lake. This legend, mentioned in Nīlamata Purāṇa, states that a tribal leader named Ananta drained a lake to kill a demon. Ananta named the site of the former lake (now land) as "Kashmir", after his father Kaśyapa.

• According to Kalla, Śakuntalā is an allegorical dramatization of Pratyabhijna philosophy (a branch of Kashmir Shaivism). Kalla further argues that this branch was not known outside of Kashmir at that time.

Still other scholars posit Garhwal in Uttarakhand to be Kalidasa's birthplace.[6]

According to folklore, a scholarly princess once decides to find a suitable groom by testing men in her kingdom for their intelligence. When no man is able to pass the test, the frustrated citizens decide to send Kālidāsa, an uneducated man, for an interview with the princess.

In another version, the court's chief minister is insulted when the princess rejects his son's marriage proposal. To avenge this insult, the minister finds the most unfit person, the shepherd Kālidāsa, to send to the princess.

In any case Kālidasa fares poorly, and is greatly humiliated by the princess. Thus challenged, he visits a Kāli temple, is inspired to learn Sanskrit, studies the Purāṇas and other ancient texts, and becomes a great poet.

He then writes three epics starting with the words of his insult: "अस्ति कश्चित् वाग्विशेष?"(asti kaścit vagviśeṣa? is there anything particularly intelligent you can now say?, implying, have you attained any profound knowledge that should make me give you a special welcome?).

From these three words he embraces, he writes his three classic books. From “asti” = asti-uttarasyaam diśi, he produces the epic “Kumārasambhava”; from “Kaścit” = kaścit-kāntā, he writes the poem “Meghadūta” and from “Vāgviśeṣa”= vāgarthāviva, he wrote the epic “Raghuvaṃśa".

Another old legend recounts that Kālidāsa visits Kumāradāsa, the king of Lanka and, because of treachery, is murdered there.[7]

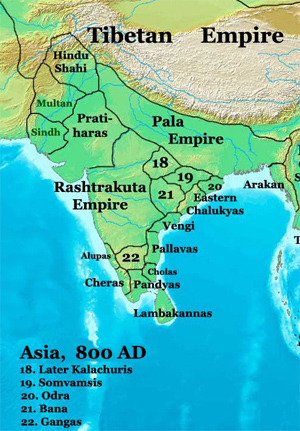

Period

Several ancient and medieval books state that Kālidāsa was a court poet of a king named Vikramāditya. A legendary king named Vikramāditya is said to have ruled from Ujjain around 1st century BCE. A section of scholars believe that this legendary Vikramāditya is not a historical figure at all. There are other kings who ruled from Ujjain and adopted the title Vikramāditya, the most notable ones being Chandragupta II (r. 380 CE – 415 CE) and Yaśodharman (6th century CE).[8]

The most popular theory is that Kālidāsa flourished during the reign of Chandragupta II, and therefore lived around the 4th-5th century CE. Several Western scholars have supported this theory, since the days of William Jones and A. B. Keith.[8] Modern western Indologists and scholars like Stanley Wolpert also support this theory.[9] Many Indian scholars, such as Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi and Ram Gupta, also place Kālidāsa in this period.[10][11] According to this theory, his career might have extended to the reign of Kumāragupta I (r. 414 – 455 CE), and possibly, to that of Skandagupta (r. 455 – 467 CE).[12][13]

The earliest paleographical evidence of Kālidāsa is found in a Sanskrit inscription dated c. 473 CE, found at Mandsaur's Sun temple, with some verses that appear to imitate Meghadūta Purva, 66; and the ṛtusaṃhāra V, 2–3, although Kālidāsa is not named.[14] His name, along with that of the poet Bhāravi, is first mentioned in a stone inscription dated 634 C.E. found at Aihole, located in present-day Karnataka.[15]

Theory of multiple Kālidāsas

Some scholars, including M. Srinivasachariar and T. S. Narayana Sastri, believe that works attributed to "Kālidāsa" are not by a single person. According to Srinivasachariar, writers from 8th and 9th centuries hint at the existence of three noted literary figures who share the name Kālidāsa. These writers include Devendra (author of Kavi-Kalpa-Latā), Rājaśekhara and Abhinanda. Sastri lists the works of these three Kalidasas as follows:[16]

1. Kālidāsa alias Mātṛgupta, author of Setu-Bandha and three plays (Abhijñānaśākuntalam, Mālavikāgnimitram and Vikramōrvaśīyam).

2. Kālidāsa alias Medharudra, author of Kumārasambhava, Meghadūta and Raghuvaṃśa.

3. Kālidāsa alias Kotijit: author of Ṛtusaṃhāra, Śyāmala-Daṇḍakam and Śṛngāratilaka among other works.

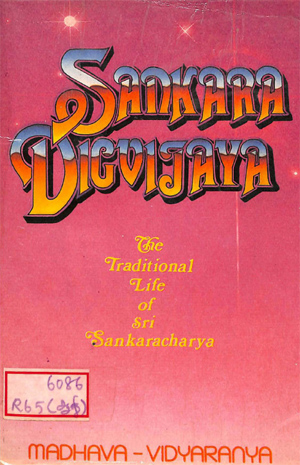

Sastri goes on to mention six other literary figures known by the name "Kālidāsa": Parimala Kālidāsa alias Padmagupta (author of Navasāhasāṅka Carita), Kālidāsa alias Yamakakavi (author of Nalodaya), Nava Kālidāsa (author of Champu Bhāgavata), Akbariya Kalidasa (author of several samasyas or riddles), Kālidāsa VIII (author of Lambodara Prahasana), and Abhinava Kālidāsa alias Mādhava (author of Saṅkṣepa-Śaṅkara-Vijayam).[16]

According to K. Krishnamoorthy, "Vikramāditya" and "Kālidāsa" were used as common nouns to describe any patron king and any court poet respectively.[17]

Works

Poems

Epic poems

Kālidāsa is the author of two mahākāvyas, Kumārasambhava (Kumāra meaning son, and sambhava meaning possibility of an event taking place, in this context a birth. Kumārasambhava thus means the birth of a son) and Raghuvaṃśa ("Dynasty of Raghu").

• Kumārasambhava describes the birth and adolescence of the goddess Pārvatī, her marriage to Śiva and the subsequent birth of their son Kumāra (Kārtikeya).

• Raghuvaṃśa is an epic poem about the kings of the Raghu dynasty.

Minor poems

Kālidāsa also wrote two khaṇḍakāvyas (minor poems):

• Descriptive:[18] Ṛtusaṃhāra describes the six seasons by narrating the experiences of two lovers in each of the seasons.[N 1]

• Elegiac: Kālidāsa created his own genre of poetry with Meghadūta (The Cloud Messenger),[18] the story of a Yakṣa trying to send a message to his lover through a cloud. Kālidāsa set this poem to the mandākrāntā meter, which is known for its lyrical sweetness. It is one of Kālidāsa's most popular poems and numerous commentaries on the work have been written.

Plays

Kālidāsa wrote three plays. Among them, Abhijñānaśākuntalam ("Of the recognition of Śakuntalā") is generally regarded as a masterpiece. It was among the first Sanskrit works to be translated into English, and has since been translated into many languages.[19]

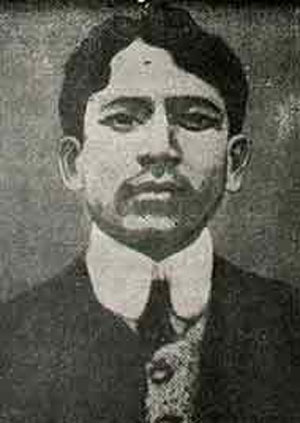

Śakuntalā stops to look back at Duṣyanta, Raja Ravi Varma (1848-1906).

• Mālavikāgnimitram (Pertaining to Mālavikā and Agnimitra) tells the story of King Agnimitra, who falls in love with the picture of an exiled servant girl named Mālavikā. When the queen discovers her husband's passion for this girl, she becomes infuriated and has Mālavikā imprisoned, but as fate would have it, Mālavikā is in fact a true-born princess, thus legitimizing the affair.

• Abhijñānaśākuntalam (Of the recognition of Śakuntalā) tells the story of King Duṣyanta who, while on a hunting trip, meets Śakuntalā, the adopted daughter of a sage, and marries her. A mishap befalls them when he is summoned back to court: Śakuntala, pregnant with their child, inadvertently offends a visiting sage and incurs a curse, whereby Duṣyanta forgets her entirely until he sees the ring he has left with her. On her trip to Duṣyanta's court in an advanced state of pregnancy, she loses the ring, and has to come away unrecognized by him. The ring is found by a fisherman who recognizes the royal seal and returns it to Duṣyanta, who regains his memory of Śakuntala and sets out to find her. Goethe was fascinated by Kālidāsa's Abhijñānaśākuntalam, which became known in Europe, after being translated from English to German.

• Vikramōrvaśīyam (Ūrvaśī Won by Valour) tells the story of King Pururavas and celestial nymph Ūrvaśī who fall in love. As an immortal, she has to return to the heavens, where an unfortunate accident causes her to be sent back to the earth as a mortal with the curse that she will die (and thus return to heaven) the moment her lover lays his eyes on the child which she will bear him. After a series of mishaps, including Ūrvaśī's temporary transformation into a vine, the curse is lifted, and the lovers are allowed to remain together on the earth.

Translations

Montgomery Schuyler, Jr. published a bibliography of the editions and translations of the drama Śakuntalā while preparing his work "Bibliography of the Sanskrit Drama".[N 2][20] Schuyler later completed his bibliography series of the dramatic works of Kālidāsa by compiling bibliographies of the editions and translations of Vikramōrvaśīyam and Mālavikāgnimitra.[21] Sir William Jones published English translation of Śakuntalā in 1791 C.E. and Ṛtusaṃhāra was published by him in original text during 1792 C.E.[22]

Influence

Kālidāsa has had great influence on several Sanskrit works, on all Indian literature.[14] He also had a great impact on Rabindranath Tagore. Meghadūta's romanticism is found in Tagore's poems on the monsoons.[23] Sanskrit plays by Kālidāsa influenced late eighteenth and early nineteenth-century European literature.[24] According to Dale Carnegie, Father of Modern Medicine Sir William Osler always kept on his desk a poem written by Kalidasa.[25]

Critical reputation

Bāṇabhaṭṭa, the 7th-century Sanskrit prose-writer and poet, has written: nirgatāsu na vā kasya kālidāsasya sūktiṣu. prītirmadhurasārdrārsu mañjarīṣviva jāyate. ("When Kālidāsa's sweet sayings, charming with sweet sentiment, went forth, who did not feel delight in them as in honey-laden flowers?")[26]

Jayadeva, a later poet, has called Kālidāsa a kavikulaguru, 'the lord of poets' and the vilāsa, 'graceful play' of the muse of poetry.[27]

Kālidāsa has been called the Shakespeare of India. The scholar and philologist Sir William Jones is said to be the first to do so. Writing about this, author and scholar MR Kale says "the very comparison of Kālidāsa to Shakespeare is the highest form of eulogy that could be bestowed upon him."[28]

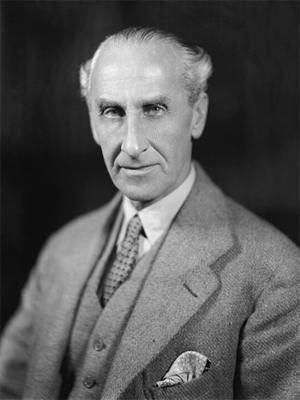

The Indologist Sir Monier Williams has written: "No composition of Kālidāsa displays more the richness of his poetical genius, the exuberance of his imagination, the warmth and play of his fancy, his profound knowledge of the human heart, his delicate appreciation of its most refined and tender emotions, his familiarity with the workings and counterworkings of its conflicting feelings - in short more entitles him to rank as the Shakespeare of India."[29]

Willst du die Blüthe des frühen, die Früchte des späteren Jahres,

Willst du, was reizt und entzückt, willst du was sättigt und nährt,

Willst du den Himmel, die Erde, mit Einem Namen begreifen;

Nenn’ ich, Sakuntala, Dich, und so ist Alles gesagt.

— Goethe

Wouldst thou the young year's blossoms and the fruits of its decline

And all by which the soul is charmed, enraptured, feasted, fed,

Wouldst thou the earth and heaven itself in one sole name combine?

I name thee, O Sakuntala! and all at once is said.

— translation by E. B. Eastwick

"Here the poet seems to be in the height of his talent in representation of the natural order, of the finest mode of life, of the purest moral endeavor, of the most worthy sovereign, and of the most sober divine meditation; still he remains in such a manner the lord and master of his creation."

— Goethe, quoted in Winternitz[30]

Philosopher and linguist Humboldt writes, "Kālidāsa, the celebrated author of the Śākuntalā, is a masterly describer of the influence which Nature exercises upon the minds of lovers. Tenderness in the expression of feelings and richness of creative fancy have assigned to him his lofty place among the poets of all nations."[31]

Later culture

Many scholars have written commentaries on the works of Kālidāsa. Among the most studied commentaries are those by Kolāchala Mallinātha Suri [estimated 1346-1440 CE], which were written in the 15th century during the reign of the Vijayanagara king, Deva Rāya II.

Based on the evidence from the inscriptions, it is estimated that he lived between 1350-1450 CE...

Mallinātha is well known as a commentator who has written glosses on Classical epics of Sanskrit, besides his commentaries on Śātric works...

Interestingly, in Marathi Language, there is a word 'Mallinathi', which means 'a comment or criticism' done by somebody.

-- Mallinātha Sūri, by Wikipedia

The earliest surviving commentaries appear to be those of the 10th-century Kashmirian scholar Vallabhadeva.[32]

For more than a millennium Kalidasa's long poem Raghuvarnsa ("The Lineage of Raghu") has been acknowledged as one of the masterpieces of Sanskrit literature. Many thousands of manuscripts survive, transmitting versions of the text, which often differ considerably, and many classical commentaries. Most of these have not yet been consulted by modern scholars, and as a result there is still no truly authoritative edition of the poem. This volume presents a critical edition of the first six chapters of the oldest commentary known to survive, by the Kashmirian scholar Vallabhadeva (10th century). This commentary has never before been published, so this is the first time that one of the most important sources for the text and the interpretation of Kalidasa's poem has been made available. Vallabhadeva's work is also of intrinsic value as one of the earliest commentaries in Sanskrit on a belletristic work. Kashmirian manuscripts of the poem have not hitherto been used by editors: ten have been collated, and their readings, which are often supported by Vallablhadeva's commentary, reported in the critical apparatus. The apparatus also records the readings of the six pre-modern commentaries that have appeared in print. The notes discuss problems of textual criticism and some questions related to the interpretation of the poem; they also report the readings of two other unpublished commentaries that are transmitted in palm-leaf manuscripts preserved in Nepal: those of Srinatha and Vaidyasrigarbha. A lengthy Introduction discusses the transmission of the poem and the commentary and the distinctive style of the latter.

-- The Raghupaãncik-a of Vallabhadeva, being the earliest commentary on the Raghuvaṃśa of K-alid-asa. Vol. 1, by Vallabhadeva, Dominic Goodall, H. Isaacson · 2003

Eminent Sanskrit poets like Bāṇabhaṭṭa [606-647 CE],

Bāṇabhaṭṭa (Sanskrit: बाणभट्ट) was a 7th-century Sanskrit prose writer and poet of India. He was the Asthana Kavi [Court Poet] in the court of King Harsha Vardhana, who reigned c. 606–647 CE in north India first from Sthanvishvara (Thanesar), and later Kannauj. Bāna's principal works include a biography of Harsha, the Harshacharita (Deeds of Harsha), and one of the world's earliest novels, Kadambari. Bāṇa died before finishing the novel and it was completed by his son Bhūṣaṇabhaṭṭa...

A detailed account regarding his ancestry and early life can be reconstructed from the introductory verses attached to the कादम्बरी and the first two ucchāvasas of the Harṣacarita..

In Harshacharit, Bana Bhatta describes himself as Vatsyayana Gotriya and Bhriguvanshi who used to reside in a village called Pritikoot. He has also described his childhood in Harshacharit. Bana Bhatta describes Pritikoot as a village on the banks of the River Son i.e. Hirnybahu. Pritikoot (now Piru) village is located in Haspura block of Aurangabad district on the eastern bank of River Son. Its distance is about 15 kilometres from Bhrigu Rishi's historical ashram (Bhrigurari), located in Goh block of Aurangabad district. According to the first chapter of [[Harshacharit>Dr. Keshavrao Musalgaonkar, Chaukhamba Sanskrit Institute, Varanasi</ref>]], Bana Bhatta has associated himself with Goddess ‘Saraswati’. According to him, due to the curse of Durvasha Rishi, once 'Saraswati' had to leave Brahmaloka and stay on earth. Her stay on earth was to end at the sight of her own son's face. Saraswati made her debut on the western bank of the Son River presently known as Shahabad region. Soon she fell in love with Dadhich, son of Bhrigukul-Vanshi-Chyawan, who used to come to meet her crossing the reiver Son. According to Harshacharit, Dadhich's father's house was situated across (in the east of) the River Son. Soon Saraswati got a son from the union with Dadhich, whose name was Saraswat. With his birth, Saraswati was freed from the curse and went back to Brahmaloka. Distracted by this separation, Dadhich handed over his son to his own Bhrigu-Vanshi brother for upbringing and himself went for penance. With the blessings of mother Saraswati, her son Saraswat knew all the Vedas and scriptures. He settled Pritikoot and later he too went to join his father to do penance. Later in the same clan, Munis [ancient Indian sages], like Vatsa...Vatsa or Vamsa (Pali and Ardhamagadhi: Vaccha, literally "calf") was one of the solasa (sixteen) Mahajanapadas (great kingdoms) of Uttarapatha of ancient India mentioned in the Anguttara Nikaya. Vatsa or Vamsa country corresponded with the territory of modern Allahabad in Uttar Pradesh, at the confluence of the Ganges and Yamuna rivers.

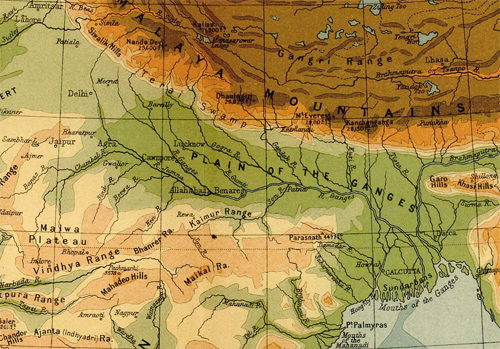

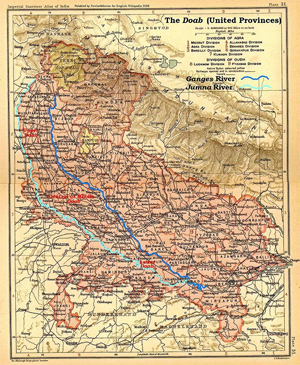

It had a monarchical form of government with its capital at Kaushambi (whose ruins are located at the modern village of Kosam, 38 miles from Allahabad). Udayana [Udayana, the romantic hero of the Svapnavāsavadattā, the Pratijñā-Yaugandharāyaṇa and many other legends was a contemporary of Buddha and of Pradyota, the king of Avanti] was the ruler of Vatsa in the 6th-5th century BCE, the time of the Buddha. His mother, Mrigavati, is notable for being one of the earliest known female rulers in Indian history.

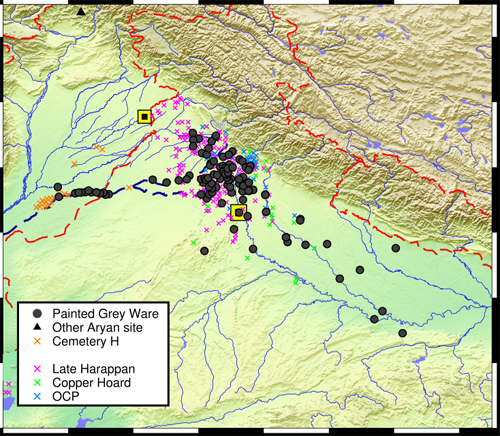

The Vatsas were a branch of the Kuru dynasty. During the Rig Vedic period, the Kuru Kingdom comprised the area of Haryana/ Delhi and the Ganga-Jamuna Doab, till Prayag/ Kaushambi, with its capital at Hastinapur. During the late-Vedic period, Hastinapur was destroyed by floods, and the Kuru King Nicakṣu shifted his capital with the entire subjects to a newly constructed capital that was called Kosambi or Kaushambi. In the post Vedic period, when Arya Varta ["Abode of the Aryas"] consisted of several Mahajanpads, the Kuru Dynasty was split between Kurus and Vatsas. The Kurus controlled the Haryana/ Delhi/ Upper Doab, while the Vatsas controlled the Lower Doab. Later, The Vatsas were further divided into two branches—One at Mathura, and the other at Kaushambi.

-- Vatsa, by Wikipedia

Vatsyayan ...Vātsyāyana is an ancient Indian philosopher, known for authoring the Kama Sutra. He lived in India during the second or third century CE, probably in Pataliputra (modern day Patna).

He is not to be confused with Pakṣilasvāmin Vātsyāyana, the author of Nyāya Sutra Bhāshya, the first preserved commentary on Gotama's Nyāya Sutras. His name is sometimes erroneously confused with Mallanaga, the seer of the Asuras, to whom the origin of erotic science is attributed.

Hardly anything is known about Vātsyāyana from sources outside the Kāmasūtra itself.

-- Vātsyāyana, by Wikipedia

and then Bana Bhatt were born. This description shows that Bana Bhatta was the resident of the eastern bank of the Son River. Chyavan Rishi's ashram is also situated in the village Deokund under the Goh block of Aurangabad district.

-- Bāṇabhaṭṭa, by Wikipedia

Jayadeva [1170-1245 CE] ...

Jayadeva (born c. 1170 CE), also known as Jaideva, was a Sanskrit poet during the 12th century...

Little is known of his life, except that he was a loner poet and a Hindu mendicant celebrated for his poetic genius in eastern India...

Inscriptions at Lingaraj temple, and the more recently discovered Madhukeswar temple and Simhachal temple that were read and interpreted by Satyanarayana Rajguru have shed some light on Jayadeva's early life.

-- Jayadeva, by Wikipedia

and Rajasekhara ...

Rajashekhara (fl. 10th century) was an eminent Sanskrit poet, dramatist and critic. He was the court poet of the Gurjara Pratiharas.

Rajashekhara wrote the Kavyamimamsa between 880 and 920 CE. The work is essentially a practical guide for poets that explains the elements and composition of a good poem...

In Bālarāmāyaṇa, he mentioned that his great grandfather Akalajalada belonged to Maharashtra. In the same work, he described his father Durduka as a Mahamantrin (minister) without providing any details. He mentioned in his works that his wife Avantisundari belonged to the Chahamana (Chauhan) family. In his works, he described himself as the teacher of the Gurjara-Pratihara ...The origin of the dynasty and the meaning of the term "Gurjara" in its name is a topic of debate among historians. The rulers of this dynasty used the self-designation "Pratihara" for their clan, and never referred to themselves as Gurjaras. They claimed descent from the legendary hero Lakshmana, who is said to have acted as a pratihara ("door-keeper") for his brother Rama....

Multiple inscriptions of their neighbouring dynasties describe the Pratiharas as "Gurjara". The term "Gurjara-Pratihara" occurs only in the Rajor inscription of a feudatory ruler named Mathanadeva, who describes himself as a "Gurjara-Pratihara"...

According to the Agnivansha legend given in the later manuscripts of Prithviraj Raso, the Pratiharas and three other Rajput dynasties originated from a sacrificial fire-pit (agnikunda) at Mount Abu...

The original centre of Pratihara power is a matter of controversy. R. C. Majumdar, on the basis of a verse in the Harivamsha-Purana, AD 783, the interpretation of which he conceded was not free from difficulty, held that Vatsaraja ruled at Ujjain...

In the Gwalior inscription, it is recorded that Gurjara-Pratihara emperor Nagabhata "crushed the large army of the powerful Mlechcha king." This large army consisted of cavalry, infantry, siege artillery, and probably a force of camels...

The Arab chronicler Sulaiman describes the army of the Pratiharas as it stood in 851 CE, "The ruler of Gurjars maintains numerous forces and no other Indian prince has so fine a cavalry. He is unfriendly to the Arabs, still he acknowledges that the king of the Arabs is the greatest of rulers. Among the princes of India there is no greater foe of the Islamic faith than he. He has got riches, and his camels and horses are numerous."

-- Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty, by Wikipedia

king Mahendrapala I.Inscriptions discovered at Ramgaya, opposite the Gadadhar temple at Gaya, at Guneria in the southern part of the Gaya district, at Itkhori in the Hazaribagh district of Bihar and at Paharpur in the northern part of the Rajshahi district of Bengal, describe his reign. [???]

The greater part of Magadha up to even northern Bengal had come under the suzerainty of the monarch Mahendrapala I.[3]:21 [Sen, S.N., 2013, A Textbook of Medieval Indian History, Delhi: Primus Books, ISBN 9789380607344]

In north his authority was extended up to the foot of the Himalayas. Gwalior was also under his control as the Siyadoni inscription mentions him the ruling sovereign in 903 and 907 A.D.. Thus, he retained the empire transmitted to him by his father Mihir Bhoja and also added some part of Bengal by defeating Palas.

In Dinajpur an inscription pillar of Mahendrapala has been found.[???]

-- Mahendrapala I, by Wikipedia

-- Rajashekhara (Sanskrit poet), by Wikipedia

have lavished praise on Kālidāsa in their tributes. A well-known Sanskrit verse ("Upamā Kālidāsasya...") praises his skill at upamā, or similes. Anandavardhana, a highly revered critic, considered Kālidāsa to be one of the greatest Sanskrit poets ever.

Ānandavardhana (c. 820–890 CE) was the author of Dhvanyāloka, or A Light on Suggestion (dhvani), a work articulating the philosophy of "aesthetic suggestion" (dhvani, vyañjanā)...

Ānandavardhana is credited with creating the dhvani theory. He wrote that dhvani (meaning sound, or resonance) is the "soul" or "essence" (ātman) of poetry (kavya)." "When the poet writes," said Ānandavardhana, "he creates a resonant field of emotions." To understand the poetry, the reader or hearer must be on the same "wavelength."

-- Anandavardhana, by Wikipedia

Of the hundreds of pre-modern Sanskrit commentaries on Kālidāsa's works, only a fraction have been contemporarily published. Such commentaries show signs of Kālidāsa's poetry being changed from its original state through centuries of manual copying, and possibly through competing oral traditions which ran alongside the written tradition.[/size][/b]

Kālidāsa's Abhijñānaśākuntalam was one of the first works of Indian literature to become known in Europe. It was first translated to English and then from English to German, where it was received with wonder and fascination by a group of eminent poets, which included Herder and Goethe.[33]

Kālidāsa's work continued to evoke inspiration among the artistic circles of Europe during the late 19th century and early 20th century, as evidenced by Camille Claudel's sculpture Shakuntala.

Koodiyattam artist and Nāṭya Śāstra scholar Māni Mādhava Chākyār (1899–1990) choreographed and performed popular Kālidāsa plays including Abhijñānaśākuntala, Vikramorvaśīya and Mālavikāgnimitra.

The Kannada films Mahakavi Kalidasa (1955), featuring Honnappa Bagavatar, B. Sarojadevi and later Kaviratna Kalidasa (1983), featuring Rajkumar and Jayaprada,[34] were based on the life of Kālidāsa. Kaviratna Kalidasa also used Kālidāsa's Shakuntala as a sub-plot in the movie.V. Shantaram made the Hindi movie Stree (1961) based on Kālidāsa's Shakuntala. R.R. Chandran made the Tamil movie Mahakavi Kalidas (1966) based on Kālidāsa's life. Chevalier Nadigar Thilagam Sivaji Ganesan played the part of the poet himself. Mahakavi Kalidasu (Telugu, 1960) featuring Akkineni Nageswara Rao was similarly based on Kālidāsa's life and work.[35]

Surendra Verma's Hindi play Athavan Sarga, published in 1976, is based on the legend that Kālidāsa could not complete his epic Kumārasambhava because he was cursed by the goddess Pārvatī, for obscene descriptions of her conjugal life with Śiva in the eighth canto. The play depicts Kālidāsa as a court poet of Chandragupta who faces a trial on the insistence of a priest and some other moralists of his time.

Asti Kashchid Vagarthiyam is a five-act Sanskrit play written by Krishna Kumar in 1984. The story is a variation of the popular legend that Kālidāsa was mentally challenged at one time and that his wife was responsible for his transformation. Kālidāsa, a mentally challenged shepherd, is married to Vidyottamā, a learned princess, through a conspiracy. On discovering that she has been tricked, Vidyottamā banishes Kālidāsa, asking him to acquire scholarship and fame if he desires to continue their relationship. She further stipulates that on his return he will have to answer the question, Asti Kaścid Vāgarthaḥ" ("Is there anything special in expression?"), to her satisfaction. In due course, Kālidāsa attains knowledge and fame as a poet. Kālidāsa begins Kumārsambhava, Raghuvaṃśa and Meghaduta with the words Asti ("there is"), Kaścit ("something") and Vāgarthaḥ ("spoken word and its meaning") respectively.

Bishnupada Bhattacharya's "Kalidas o Robindronath" is a comparative study of Kalidasa and the Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore.

Ashadh Ka Ek Din is a Hindi play based on fictionalized elements of Kalidasa's life.

See also

· Sanskrit literature

· Sanskrit drama

· Bhāsa

· Bhavabhūti

References

1. "Kalidasa - Kalidasa Biography - Poem Hunter". www.poemhunter.com. Retrieved 5 October2015.

2. Kālidāsa (2001). The Recognition of Sakuntala: A Play In Seven Acts. Oxford University Press. pp. ix. ISBN 9780191606090.

3. Gopal 1984, p. 3.

4. P. N. K. Bamzai (1 January 1994). Culture and Political History of Kashmir. 1. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. pp. 261–262. ISBN 978-81-85880-31-0.

5. M. K. Kaw (1 January 2004). Kashmir and Its People: Studies in the Evolution of Kashmiri Society. APH Publishing. p. 388. ISBN 978-81-7648-537-1.

6. Shailesh, H D Bhatt. The Story of Kalidas. Publications Division Ministry of Information & Broadcasting. ISBN 9788123021935.

7. "About Kalidasa". Kalidasa Academi. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

8. Chandra Rajan (2005). The Loom Of Time. Penguin UK. pp. 268–274. ISBN 9789351180104.

9. Wolpert, Stanley (2005). India. University of California Press. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-520-24696-6.

10. Vasudev Vishnu Mirashi and Narayan Raghunath Navlekar (1969). Kālidāsa; Date, Life, and Works. Popular Prakashan. pp. 1–35. ISBN 9788171544684.

11. Gopal 1984, p. 14.

12. C. R. Devadhar (1999). Works of Kālidāsa. 1. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. vii–viii. ISBN 9788120800236.

13. Sastri 1987, pp. 77–78.

14. Gopal 1984, p. 8.

15. Sastri 1987, p. 80.

16. M. Srinivasachariar (1974). History of Classical Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 112–114. ISBN 9788120802841.

17. K. Krishnamoorthy (1994). Eng Kalindi Charan Panigrahi. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 9–10. ISBN 978-81-7201-688-3.

18. Kalidasa Translations of Shakuntala, and Other Works. J. M. Dent & sons, Limited. 1 January 1920.

19. "Kalidas". www.cs.colostate.edu. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

20. Schuyler, Jr., Montgomery (1901). "The Editions and Translations of Çakuntalā". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 22: 237–248. doi:10.2307/592432. JSTOR 592432.

21. Schuyler, Jr., Montgomery (1902). "Bibliography of Kālidāsa's Mālavikāgnimitra and Vikramorvaçī". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 23: 93–101. doi:10.2307/592384. JSTOR 592384.

22. Sastri 1987, p. 2.

23. "Rabindranath Tagore on Kalidasa's Meghadoota". Cloud and Sunshine. 16 September 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

24. "Translations of Shakuntala and Other Works - Online Library of Liberty". oll.libertyfund.org. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

25. Carnegie, Dale (2017). How to Stop Worrying and Start Living. Manjul Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-8322-802-2.

26. Kale, p. xxiv.

27. Kale, p. xxv.

28. Kale, p. xxvi.

29. Kale, pp. xxvi-xxvii.

30. Maurice Winternitz; Moriz Winternitz (1 January 2008). History of Indian Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 238. ISBN 978-81-208-0056-4.

31. Kale, p. xxvii.

32. Vallabhadeva; Goodall, Dominic; Isaacson, H. (2003). The Raghupaãncik-a of Vallabhadeva. E. Forsten. ASIN 9069801388 Check |asin= value (help). ISBN 978-90-6980-138-4. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w76wzr.11.

33. Haksar, A. N. D. (1 January 2006). Madhav & Kama: A Love Story from Ancient India. Roli Books Private Limited. pp. 58. ISBN 978-93-5194-060-9.

34. Kavirathna Kaalidaasa (1983) - IMDb, retrieved 7 April 2021

35. Rao, Kamalakara Kameshwara, Mahakavi Kalidasu (Drama, History, Musical), Akkineni Nageshwara Rao, S. V. Ranga Rao, Sriranjani, Seeta Rama Anjaneyulu Chilakalapudi, Sarani Productions, retrieved 7 April 2021

Notes

1. Ṛtusaṃhāra was translated into Tamil by Muhandiram T. Sathasiva Iyer.

2. It was later published as the third volume of the 13-volume Columbia University Indo-Iranian Series, published by the Columbia University Press in 1901-32 and edited by A. V. Williams Jackson.

Citations

· Raghavan, V. (January–March 1968). "A Bibliography of translations of Kalidasa's works in Indian Languages". Indian Literature. 11 (1): 5–35. JSTOR 23329605.

· Śāstrī, Gaurīnātha (1987). A Concise History of Classical Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0027-4.

· Gopal, Ram (1 January 1984). Kālidāsa: His Art and Culture. Concept Publishing Company.

· Kale, M.R. The Abhijñānaśākuntalam of Kālidāsa. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120802834.

Further reading

· Kālidāsa (1984). Miller, Barbara Stoler (ed.). The Plays of Kālidāsa: Theater of Memory. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-81-208-1681-7.

· Sethna, Kaikhushru Dhunjibhoy (2000). Problems of Ancient India. Aditya Prakashan. pp. 79–120. ISBN 978-81-7742-026-5.

· Venkatachalam, V. (1986). "Kalidasa Special Number (X), The Vikram". Bhāsa. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 130–140.

External links

· Media from Wikimedia Commons

· Quotations from Wikiquote

· Texts from Wikisource

· Data from Wikidata

· Kalidasa at the Encyclopædia Britannica

· Kalidasa: Translations of Shakuntala and Other Works by Arthur W. Ryder

· Biography of Kalidasa

· Works by Kalidasa at Project Gutenberg

· Works by or about Kalidasa at Internet Archive

· Works by Kalidasa at WorldCat Identities

· Clay Sanskrit Library publishes classical Indian literature, including the works of Kalidasa with Sanskrit facing-page text and translation. Also offers searchable corpus and downloadable materials.

· Kalidasa at The Online Library of Liberty

· Kalidasa at IMDb

· Kalidasa at Banglapedia

· Epigraphical Echoes of Kalidasa