by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/30/21

That the author of RC did not entertain a favourable opinion about Mahipala II is quite clear from the way in which he describes these two incidents, and specially from the words and phrases used in connection with them to describe the king’s character. It is, however, noteworthy, that while the episode of the great rebellion and the part played by the king therein are alluded to merely by way of a casual reference, in short detached phrases, unintelligible without the help of the commentary, the imprisonment of Ramapala is described at length in six verses (I. 32-7). This is an important indication that the author’s judgment of Mahipala was influenced mainly by the latter event. In other words, he considered Mahipala far more blameworthy for his conduct towards Ramapala than for the folly which led to the loss of Varendra. If we remember the open and professed partisanship of Sandhyakaranandi for his hero Ramapala, we should be cautious in accepting, at its face value, both his judgment of the king and his version of the cause and nature of the imprisonment of Ramapala. As regards the other incident which cost Mahipala his life and throne, if the commentator's view is to be accepted, the gravamen of the charge brought by the author against Mahipala consists of his lack of wisdom and good policy (aniti, durnnaya) and an inordinate passion for war (yuddha-vyasana) which led him to undertake a rash military enterprise in spite of the advice of his ministers to the contrary. Apart from these two specific incidents the RC contains only one general reference to the character of Mahipala, in which he is described as ‘rajapravara’ which the commentator explains as nrpatisrestha or excellent king (I. 29). This passing reference, unconnected with any special incident, seems to indicate that Sandhyakaranandi did not fail to appreciate the general merits of Mahipala as a king, although he disapproved of his conduct towards his brothers.

But whatever view we might take of the attitude of the author towards Mahipala, there is absolutely no justification for the following statement made by MM. Sastri:

“Mahipala by his impolitic acts incurred the displeasure of his subjects ..... The Kaivartas were smarting under oppression of the king. Bhima, the son of Rudoka, taking advantage of the popular discontent, led his Kaivarta subjects to rebellion.” (p. 13)

There is not a word in RC to show that Mahipala incurred the displeasure of his subjects by his impolitic acts or that there was a general popular discontent against him. It is an amazing invention to say that “the Kaivartas were smarting under oppression of the king," for the RC does not contain a single word which can even remotely lead to such a belief. It is a travesty of facts to hold that Bhima led his Kaivarta subjects (?) to rebellion. The rebellion was led by a number of feudal vassals and there is no evidence to show that they belonged solely, or even primarily, to the Kaivarta caste. There is again nothing to show that Bhima had anything to do with the rebellion, far less that he led it. Such an assumption seems to be absurd in view of the fact that he was the third king in succession after Divya who occupied the throne of Varendra after the rebellion. There is again nothing in RC to show that during the reign of Mahipala the Kaivartas formed a distinct political entity under Divya or Bhima, so that they might be regarded as the subjects of the latter.

This tissue of misstatements, unsupported by anything in the text of RC, is responsible for a general belief that Mahipala was an oppressive king, and has even led sober historians to misjudge his character and misconstrue the events of his reign. A popular myth has been sedulously built up to the effect that there was a general rising of people which cost Mahipala his life and throne, that it was merely a popular reaction against the oppression and wickedness of the king, and that, far from being rebellious in character, it was an assertion of the people’s right to dethrone a bad and unpopular king and elect a popular chief in his place. In other words, in fighting and killing Mahipala the people of Varendra were inspired by the noblest motive of saving the country from his tyranny and anarchy. Some even proceeded so far as to say that this act was followed by a general election of Divya as the king of Varendra, and a great historian has compared the whole episode with that which led to the election of Gopala, the founder of the Pala dynasty, to the throne of Bengal.1 [ A movement has been set on foot by a section of the Kaivarta or Mahisya community in Bengal to perpetuate the memory of Divya, on the basis of the view-points noted above. They refuse to regard him as a rebel and hold him up as a great hero called to the throne by the people of Varendra to save it from the oppressions of Mahipala. An annual ceremony — Divya-smriti-utsava -- is organized by them and the speeches, made on these occasions by eminent historians like Sir Jadunath Sarkar, Rai Bahadur Rama Prasad Chanda, and Dr. Upendranath Ghoshal [1886-1969; President of The Asiatic Society of Bengal 1963-1964; Author of: Studies in Indian history and culture (1957); A History of Hindu Political Theories: From the Earliest Times to the End of the First Quarter of the Seventeenth Century A.D. (1927); A History of Indian Public Life (1966); Ancient Indian culture in Afghanistan (1928); Contributions to the history of the Hindu revenue system (1929); The agrarian syste in ancient India (1930)] who presided over the function seek to support the popular views. On the other hand attempts have been made to show that these popular views are not supported by the statements in Ramacarita (cf. Bharatavarsa, 1342, pp. 18 ff.).]

This is not the proper place or occasion to criticise these views at length, or to refer to many other important conclusions which have been drawn from MM. Sastri’s sketch of the life and character of Mahipala. But in view of the deep-rooted prejudices and errors which are still current in spite of the exposition of the unwarranted character of MM. Sastri’s interpretation, it is necessary to draw attention to what is really stated in RC about the great rebellion and the part played by Divya. The author of RC did not regard the rising in any other light than a dire calamity which enveloped the kingdom in darkness (I. 22). He describes it as anika dharma-viplava or the unholy or unfortunate civil revolution (1. 24), bhavasya apadam or the calamity of the world, and damaram which the commentator explains as upaplava or disturbance (I. 27). Further, the latter describes it as merely a rebellion of feudal vassals (ananta-samanta-cakra), and not a word is said about its popular character. There is even no indication that the rebels belonged to Varendra or that the encounter between Mahipala and the rebels took place within that province. Such revolts were not uncommon in different parts of the Pala kingdom in those days. Similar revolts placed in power the Kamboja chiefs in Varendra and Radha, and the family of Sudraka in Gaya district.1 [For a detailed discussion of this point and a view of Divya’s rebellion in its true perspective cf. Dr. R C. Majumdar’s article ‘The Revolt of Divvoka against Mahipala II and other revolts in Bengal’ in Dacca University Studies Vol. I, No. 2, pp. 125 ff.]

There is not a word in RC to the effect that Divya2 [The name is written variously in RC as Divya (1. 38), Divvoka (1. 38-39 commentary), and Divoka (I. 31 commentary).] was the leader of a popular rebellion, far less that he was elected as king by the people. As a matter of fact his name is not associated in any way even with the fight between Mahipala and his rebellious chiefs (milit-ananta-samanta-cakra) referred to in Verse I. 31. The RC only tells us that “Ramapala’s beautiful fatherland (Varendri) was occupied by his enemy named Divya, an (officer) sharing royal fortune, who rose to a high position, (but) who took to fraudulent practice as a vow” (I. 38). The account given in RC is not incompatible with the view that Mahipala met with a disastrous defeat in an encounter with some rebellious vassals in or outside Varendra, and Divya took advantage of it to seize the throne for himself. That the author of RC did not entertain any favourable view of the character and policy of Divya is clear from the two adjectives applied to him, viz., dasyu and upadhivrati. The commentator says ‘dasyuna satruna tadbhavapannatvat.’ It is obvious that the commentator means that the term dasyu refers to the enemy (Divya) as he had assumed the character of a dasyu (enemy). As to the other expression upadhivrati, the commentator first explains vrata as ‘something which is undertaken as an imperative duty,’ and then adds ‘chadmani vrati.’ In other words, Divya performed an act on the plea that it was an imperative duty, but this was a merely false pretension. In any case the two words in the text ‘dasyu’ and ‘upadhi’ cannot be taken by any stretch of imagination to imply any good or noble trait in his character.

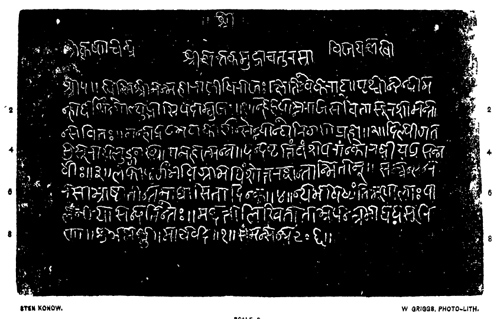

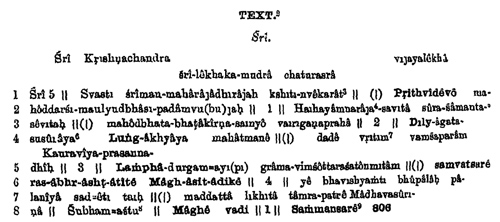

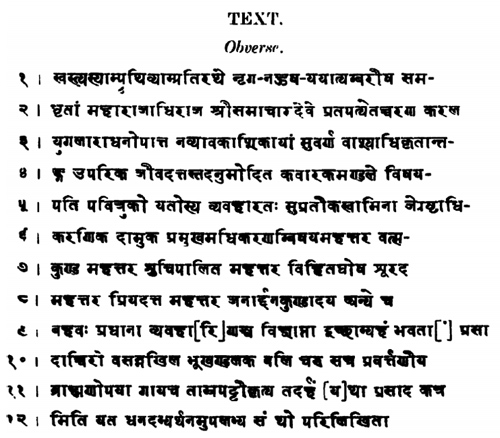

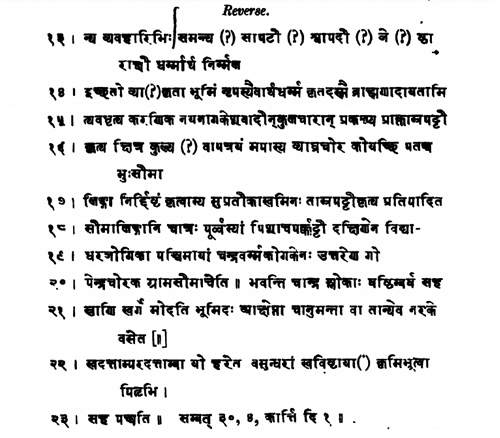

-- The Ramacaritam of Sandhyakaranandin, by Dr. R. C. Majumdar, M.A., Ph.D., Dr. Radhagovinda Basak, M.A., Ph.D., and Pandit Nanigopal Banerji, Kavyatirtha

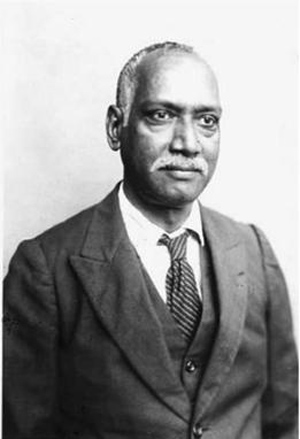

Sir Jadunath Sarkar

Jadunath Sarkar, c. 1926[1]

Born: 10 December 1870, Karachmaria, Singra, Natore, British India

Died: 19 May 1958 (aged 87), Calcutta, India

Occupation: Historian

Spouse(s): Lady Kadambini Sarkar

Sir Jadunath Sarkar CIE (10 December 1870 – 19 May 1958) was a prominent Indian historian especially of the Mughal dynasty.

Academic career

Sarkar was born in Karachmaria village in Natore, Bengal to Rajkumar Sarkar, the local Zamindar on 10 December 1870.[2] In 1891, he graduated in English from Presidency College, Calcutta.[2] In 1892, he topped the Master of Arts examination, in English at Calcutta University and in 1897, he received the Premchand-Roychand Scholarship.[2]

In 1893, he was inducted as a faculty of English literature at Ripon College, Calcutta (later renamed Surendranath College).[2] In 1898, he was appointed at Presidency College, Calcutta after getting selected in the Provincial Education Services.[2] In between, from 1917 to 1919, he taught Modern Indian History in Benaras Hindu University and from 1919–1923, both English and History, at Ravenshaw College, Cuttack.[2] In 1923, he became an honorary member of the Royal Asiatic Society of London. In August 1926, he was appointed as the Vice Chancellor of Calcutta University. In 1928, he joined as Sir W. Meyer Lecturer in Madras University.

Historiography

Reception

Sarkar's works faded out of public memory, with the increasing advent of Marxist and postcolonial schools of historiography.[3]

Academically, Jos J. L. Gommans compares Sarkar's work with those of the Aligarh historians, noting that while the historians from the Aligarh worked mainly on the mansabdari system and gunpowder technology in the Mughal Empire, Sarkar concentrated on military tactics and sieges.[4]

Aligarh Muslim University (abbreviated as AMU) is a public central university in Aligarh, India, which was originally established by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in 1875. Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College became Aligarh Muslim University in 1920, following the Aligarh Muslim University Act...

The university was established as the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College in 1875 by Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, starting functioning on 24 May 1875. The movement associated with Syed Ahmad Khan and the college came to be known as the Aligarh Movement, which pushed to realise the need for establishing a modern education system for the Indian Muslim populace. He considered competence in English and Western sciences necessary skills for maintaining Muslims' political influence. Khan's vision for the college was based on his visit to Oxford University and Cambridge University, and he wanted to establish an education system similar to the British model.

A committee was formed by the name of foundation of Muslim College and asked people to fund generously. Then Viceroy and Governor General of India, Thomas Baring gave a donation of ₹10,000 while the Lt. Governor of the North Western Provinces contributed ₹1,000, and by March 1874 funds for the college stood at ₹1,53,920 and 8 ana. Maharao Raja Mahamdar Singh Mahamder Bahadur of Patiala contributed ₹58,000 while Raja Shambhu Narayan of Benaras donated ₹60,000. Donations also came in from the Maharaja of Vizianagaram as well. The college was initially affiliated to the University of Calcutta for the matriculate examination but became an affiliate of Allahabad University in 1885. The 7th Nizam of Hyderabad, HEH Mir Osman Ali Khan made a remarkable donation of Rupees 5 Lakh to this institution in the year 1918...

Before 1939, faculty members and students supported an all-India nationalist movement but after 1939, political sentiment shifted towards support for a Muslim separatist movement. Students and faculty members supported Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the university came to be a center of the Pakistan Movement.

Dr. Sheikh Abdullah ("Papa Mian") is the founder of the women's college of Aligarh Muslim University and had pressed for women's education, writing articles while also publishing a monthly women's magazine, Khatoon. To start the college for women, he had led a delegation to the Lt. Governor of the United Provinces while also writing a proposal to Sultan Jahan, Begum of Bhopal. Begum Jahan had allocated a grant of ₹ 100 per month for the education of women. On 19 October 1906, he successfully started a school for girls with five students and one teacher at a rented property in Aligarh. The foundation stone for the girls' hostel was laid by him and his wife, Waheed Jahan Begum ("Ala Bi") after struggles on 7 November 1911. Later, a high school was established in 1921, gaining the status of an intermediate college in 1922, finally becoming a constituent of the Aligarh Muslim University as an undergraduate college in 1937. Later, Dr. Abdullah's daughters also served as principals of the women's college. One of his daughters was Mumtaz Jahan Haider, during whose tenure as principal, Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad had visited the university and offered a grant of ₹9,00,000. She was involved in the establishment of the Women's College, organised various extracurricular events, and reasserted the importance of education for Muslim women.

-- Aligarh Muslim University, by Wikipedia

He has been called the "greatest Indian historian of his time" and one of the greatest in the world, whose erudite works "have established a tradition of honest and scholarly historiography" by E. Sreedharan.[5] He has also been compared with Theodor Mommsen and Leopold von Ranke.[5]

Honors

Sarkar was honored by Britain with a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire CIE and knighted in the 1929 Birthday Honours list.[6] He was invested with his knighthood at Simla by the acting Viceroy, Lord Goschen, on 22 August 1929.[7]

Legacy

The Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, an autonomous research center, has been established in his house, which was donated to the state government by Sarkar's wife. CSSC also houses the Jadunath Bhavan Museum and Resource Centre, a museum-cum-archive of primary sources.[8]

List of works

Published works by Sarkar include:

• Economics of British India (1900)

• The India of Aurangzib (1901)

• Anecdotes of Aurangzib (1912)

• History of Aurangzib (in 5 volumes), (1912–24)

• Chaitanya's pilgrimages and teachings, from his contemporary Bengali biography, the Chaitanya-charit-amrita: Madhya-lila (translation from the Bengali original by Krishnadasa Kaviraja, 1913)

Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (a.k.a. Mahāprabhu or "Great Lord") was a 15th century Indian saint, considered God, and founder of Achintya Bheda Abheda. Devotees consider him an incarnation of Krishna. Chaitanya Mahaprabhu's mode of worshipping Krishna with ecstatic song and dance had a profound effect on Vaishnavism in Bengal. He was also the chief proponent of the Vedantic philosophy of Achintya Bheda Abheda. Mahaprabhu founded Gaudiya Vaishnavism (a.k.a. Brahma-Madhva-Gaudiya Sampradaya). He expounded Bhakti yoga and popularized the chanting of the Hare Krishna Maha-mantra.He composed the Shikshashtakam (eight devotional prayers).

He is sometimes called Gauranga or Gaura due to his molten gold like complexion. His birthday is celebrated as Gaura-purnima. He is also called Nimai due to him being born underneath a Neem tree.

-- Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, by Wikipedia

• Shivaji and his Times (1919)

Shivaji Bhonsale I ( c. 1627 / February 19, 1630 – April 3, 1680) was an Indian ruler and a member of the Bhonsle Maratha clan. Shivaji carved out an enclave from the declining Adilshahi sultanate of Bijapur that formed the genesis of the Maratha Empire. In 1674, he was formally crowned the Chhatrapati (emperor) of his realm at Raigad.

Over the course of his life, Shivaji engaged in both alliances and hostilities with the Mughal Empire, the Sultanate of Golkonda and the Sultanate of Bijapur, as well as with European colonial powers. Shivaji's military forces expanded the Maratha sphere of influence, capturing and building forts, and forming a Maratha navy. Shivaji established a competent and progressive civil rule with well-structured administrative organisations. He revived ancient Hindu political traditions and court conventions and promoted the usage of the Marathi language.

Shivaji's legacy was to vary by observer and time, but nearly two centuries after his death, he began to take on increased importance with the emergence of the Indian independence movement, as many Indian nationalists elevated him as a proto-nationalist and hero of the Hindus.

-- Shivaji, by Wikipedia

• Studies in Mughal India (1919)[9]

• Mughal Administration (1920)[9]

• Nadir Shah in India (1922)

• Later Mughals by William Irvine (in 2 volumes), (edited by Jadunath Sarkar, 1922)

• India through the ages (1928)

• A Short History of Aurangzib (1930)

• The Fall of the Mughal Empire (in 4 volumes), (1932–38)

• Studies in Aurangzib's reign (1933)

• The House of Shivaji (1940)

• The History of Bengal (in 2 volumes), (1943–1948)

• Maāsir-i-ʻĀlamgiri: a history of the emperor Aurangzib-ʻl̀amgir (translation from the Persian original by Muḥammad Sāqī Mustaʻidd Khān, 1947)[10]

• Military History of India (1960)

• A History of Jaipur, c. 1503-1938 (1984)[11]

• A History Of Dasnami Naga Sanyasis

Dashanami (IAST Daśanāmi Saṃpradāya "Tradition of Ten Names"), also known as the Order of Swamis, is a Hindu monastic tradition of "single-staff renunciation" (ēka daṇḍi saṃnyāsī) generally associated with the Vedanta tradition and organized in its present form by 5th-century BCE theologian Adi Shankara.

A swami, as the monk is called, is a renunciate who seeks to achieve spiritual union with the swa (Self). In formally renouncing the world, he or she generally wears ochre, saffron or orange-colored robes as a symbol of non-attachment to worldly desires, and may choose to roam independently or join an ashram or other spiritual organizations, typically in an ideal of selfless service. Upon initiation, which can only be done by another existing Swami, the renunciate receives a new name (usually ending in ananda, meaning 'supreme bliss') and takes a title which formalizes his connection with one of the ten subdivisions of the Swami Order. A swami's name has a dual significance, representing the attainment of supreme bliss through some divine quality or state (i.e. love, wisdom, service, yoga), and through a harmony with the infinite vastness of nature, expressed in one of the ten subdivision names: Giri (mountain), Puri (tract), Bhāratī (land), Vana (forest), Āraṇya (forest), Sagara (sea), Āśrama (spiritual exertion), Sarasvatī (wisdom of nature), Tīrtha (place of pilgrimage), and Parvata (mountain). A swami is not necessarily a yogi, although many swamis can and do practice yoga as a means of spiritual liberation; experienced swamis may also take disciples.

Dashanami Sannyāsins are associated mainly with the four maṭhas, established in four corners of India by Shankara himself; however, the association of the Dasanāmis with the Shankara maṭhas remained nominal. The early swamis, elevated into the order as disciples of Shankara, were sannyāsins who embraced sannyas either after marriage or without getting married...

Naga Sadhu performing ritual bath at Sangam during Prayagraj Ardh Kumbhmela 2007

In the 16th century, Madhusudana Saraswati of Bengal organised a section of the Naga (naked) tradition of armed sannyasis in order to protect Hindus from the tyranny of the Mughal rulers. These are also called Goswami, Gusain, Gussain, Gosain, Gossain, Gosine, Gosavi, Sannyāsi.

Warrior-ascetics could be found in Hinduism from at least the 1500s and as late as the 1700s, although tradition attributes their creation to Sankaracharya.

Some examples of Akhara currently are the Juna Akhara of the Dashanami Naga, Niranjani Akhara, Anand Akhara, Atal Akhara, Awahan Akhara, Agni Akhara and Nirmal Panchayati Akhara at Allahabad. Each akhara is divided into sub-branches and traditions. An example is the Dattatreya Akhara (Ujjain) of the naked sadhus of Juna Naga establishment.

The naga sadhus generally remain in the ambit of non-violence presently, though some sections are also known to practice the sport of Indian wrestling. The Dasanāmi sannyāsins practice the Vedic and yogic Yama principles of ahimsā (non-violence), satya (truth), asteya (non-stealing), aparigraha (non-covetousness) and brahmacārya (celibacy / moderation).

The naga sadhus are prominent at Kumbh mela, where the order in which they enter the water is fixed by tradition. After the Juna akhara, the Niranjani and Mahanirvani Akhara proceed to their bath. Ramakrishna Math Sevashram are almost the last in the procession.

-- Dashanami Sampradaya, by Wikipedia

References

1. Chakrabarty 2015, p. ii.

2. "Sarkar, Jadunath - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

3. Kaushik Roy (2004). India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Orient Blackswan. p. 10. ISBN 978-81-7824-109-8.

4. Jos J. L. Gommans (2002). Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire, 1500-1700. Psychology Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-415-23989-9.

5. A Textbook of Historiography, 500 B.C. to A.D. 2000, E. Sreedharan, p. 448

6. The London Gazette, 3 June 1929

7. "Viewing Page 6245 of Issue 33539". London-gazette.co.uk. 1 October 1929. Retrieved 26 March2014.

8. "In the memory of Jadunath Sarkar". The Telegraph. Retrieved 30 November 2019.

9. Moreland, W. H. (July 1921). "Studies in Mughal India by Jadunath Sarkar; Mughal Administration by Jadunath Sarkar". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 3 (3): 438–439. JSTOR 25209765.

10. Davies, C. Collin (April 1949). "Maāsir-i-'Ālamgīrī of Sāqī Must'ad Khān by Jadunath Sarkar". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 1 (1): 104–106. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00102692. JSTOR 25222314.

11. Smith, John D. (1985). "Jadunath Sarkar: A History of Jaipur, c. 1503-1938". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 48 (3): 620. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00039343. JSTOR 618587.

Sources

• Chakrabarty, Dipesh (2015). The Calling of History: Sir Jadunath Sarkar and His Empire of Truth. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-10044-9.

Further reading[edit]

• Pawar, Kiram (1985). Sir Jadunath Sarkar: a profile in historiography. Books & Books.

• Sir Jadunath Sarkar commemoration volumes by Hari Ram Gupta

External links

• Ray, Aniruddha (2012). "Sarkar, Jadunath". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

• Sir Sarkar at Britannica Encyclopedia

• Works by Jadunath Sarkar at Project Gutenberg

• Works by or about Jadunath Sarkar at Internet Archive