by Wikipedia

Accessed" 5/10/21

The Most Honourable, The Marquess of Dalhousie, KT PC

Governor-General of India

In office: 12 January 1848 – 28 February 1856

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: Lord John Russell; The Earl of Derby; The Earl of Aberdeen; The Viscount Palmerston

Preceded by: The Viscount Hardinge

Succeeded by: The Viscount Canning

President of the Board of Trade

In office: 5 February 1845 – 27 June 1846

Monarch: Victoria

Prime Minister: Sir Robert Peel

Preceded by: William Ewart Gladstone

Succeeded by: The Earl of Clarendon

Personal details

Born: 22 April 1812, Dalhousie Castle, Midlothian, Scotland

Died: 19 December 1860 (aged 48), Dalhousie Castle, Midlothian

Citizenship: United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland

Spouse(s): Lady Susan Hay (d. 1853)

Alma mater: Christ Church, Oxford

Known for: Doctrine of Lapse

James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, 1st Marquess of Dalhousie KT PC (22 April 1812 – 19 December 1860), also known as Lord Dalhousie, styled Lord Ramsay until 1838 and known as The Earl of Dalhousie between 1838 and 1849, was a Scottish statesman and colonial administrator in British India. He served as Governor-General of India from 1848 to 1856.

He established the foundations of the modern educational system in India by adding mass education in addition to elite higher education. He introduced passenger trains in railways, the electric telegraph and uniform postage, which he described as the "three great engines of social improvement". He also founded the Public Works Department in India.[1] To his supporters he stands out as the far-sighted Governor-General who consolidated East India Company rule in India, laid the foundations of its later administration, and by his sound policy enabled his successors to stem the tide of rebellion.[2]

His period of rule in India directly preceded the transformation into the Victorian Raj period of Indian administration. He was denounced by many in Britain on the eve of his death as having failed to notice the signs of the brewing Indian Rebellion of 1857, having aggravated the crisis by his overbearing self-confidence, centralizing activity and expansive annexations.

Early life

James Andrew Broun-Ramsay was the third and youngest son of George Ramsay, 9th Earl of Dalhousie (1770–1838), one of Wellington's generals, who, after being Governor General of Canada, became Commander-in-Chief in India, and of his wife, Christian (née Broun) of Coalstoun, Haddingtonshire (East Lothian).[2]

The 9th Earl was in 1815 created Baron Dalhousie of Dalhousie Castle in the Peerage of the United Kingdom,[3] and had three sons,[2] of whom the two elder died young. James Andrew Broun-Ramsay, his youngest son, was described as small in stature, with a firm chiseled mouth and high forehead.

Several years of his early boyhood were spent with his father and mother in Canada. Returning to Scotland he was prepared for Harrow School, where he entered in 1825. Two years later he and another student, Robert Adair, were expelled after bullying and nearfly causing the death of George Rushout, nephew of John Rushout, 2nd Baron Northwick.[4] Until he entered university, Dalhousie's entire education being entrusted to the Rev. Mr Temple, incumbent of a quiet parish in Staffordshire.[2]

In October 1829, he passed on to Christ Church, Oxford, where he worked fairly hard, won some distinction, and made many lifelong friends. His studies, however, were so greatly interrupted by the protracted illness and death in 1832 of his only surviving brother, that Lord Ramsay, as he then became, had to content himself with entering for a pass degree, though he was placed in fourth class of honours for Michaelmas 1833. He then travelled in Italy and Switzerland, enriching with copious entries the diary which he religiously kept up through life, and storing his mind with valuable observations.[2]

Early political career

Susan, Marchioness of Dalhousie

An unsuccessful but courageous contest at the general election in 1835 for one of the seats in parliament for Edinburgh, fought against such veterans as the future speaker, James Abercrombie, afterwards Lord Dunfermline, and John Campbell, future lord chancellor, was followed in 1837 by Ramsay's return to the House of Commons as member for Haddingtonshire. In the previous year he had married Lady Susan Hay, daughter of the Marquess of Tweeddale, whose companionship was his chief support in India, and whose death in 1853 left him a heartbroken man. In 1838 his father had died after a long illness, while less than a year later he lost his mother.[2]

Succeeding to the peerage, the new earl soon made his mark in a speech delivered on 16 June 1840 in support of Lord Aberdeen's Church of Scotland Benefices Bill, a controversy arising out of the Auchterarder case, in which he had already taken part in the General Assembly in opposition to Dr Chalmers. In May 1843 he became Vice-President of the Board of Trade, Gladstone being President, and was sworn in as a privy counsellor.[2] He was also given the honorary post of Captain of Deal Castle the same year.[5]

Succeeding Gladstone as President of the Board of Trade in 1845, he threw himself into the work during the crisis of the Railway Mania with such energy that his health partially broke down under the strain. In the struggle over the Corn Laws he ranged himself on the side of Sir Robert Peel, and, after the failure of Lord John Russell to form a ministry he resumed his post at the board of trade, entering the cabinet on the retirement of Lord Stanley. When Peel resigned office in June 1846, Lord John offered Dalhousie a seat in the cabinet, an offer which he declined from a fear that acceptance might involve the loss of public character.[2] Another attempt to secure his politics.[clarification needed]

India

As Governor-General of India and Governor of Bengal on 12 January 1848, and shortly afterwards he was honoured with the green ribbon of the Order of the Thistle.[2] During this period, he was an extremely hard worker, often working sixteen to eighteen hours a day. The shortest workday Dalhousie would take began at half-past eight and would continue until half-past five, remaining at his desk even during lunch.[6] During this period, he sought to expand the reach of the empire and rode long distances on horseback, in spite of having a bad back.[7]

In contrast to many of the past leaders of the British Empire in India, he saw himself as an Orientalist monarch and believed his rule was that of a modernizer, attempting to bring the British intellectual revolution to India. A staunch utilitarian, he sought to improve Indian society under the prevalent Benthamite ideals of the period. However, in his attempt to do so he ruled with authoritarianism, believing these means were the most likely to increase the material development and progress of India. His policies, especially the doctrine of lapse, contributed to a growing sense of discontent among sectors of Indian society and therefore greatly contributed to the Great Indian Uprising of 1857, which directly followed his departure from India.[8]

In 1849, under Dalhousie's command, the British captured the princely state of Punjab. He also commanded the Second Burmese War in 1852, resulting in the capture of parts of Burma. Under his reign, the British implemented the policy of 'lapse and annexation' which ensured that if a king did not have any sons for a natural heir, the kingdom would be annexed to the British Empire. Using this policy, the British annexed some of the princely states. The annexation of Awadh made Dalhousie very unpopular in the region. This and other callous actions of the governor-general created bitter feelings among the Indian soldiers in the British Army, which finally led to the Indian Rebellion of 1857. Dalhousie and the British called this uprising the 'Sepoy mutiny' - Sepoy being the common term for native Indian soldiers in British service. Dalhousie was an able administrator, though forceful and tough. His contribution in the development of communication — railways, roads, postal and telegraph services — contributed to the modernization and unity of India. His notable achievement was the creation of modern, centralized states

Shortly after assuming his duties, in writing to the president of the Board of Control, Sir John Hobhouse, he was able to assure him that everything was quiet. This statement, however, was to be falsified by events almost before it could reach Britain.[2]

Second Anglo-Sikh War

On 19 April 1848 Vans Agnew of the civil service and Lieutenant Anderson of the Bombay European regiment, having been sent to take charge of Multan from Diwan Mulraj, were murdered there, and within a short time the troops and sardars joined in open rebellion. Dalhousie agreed with Sir Hugh Gough, the commander-in-chief, that the British East India Company's military forces were neither adequately equipped with transport and supplies, nor otherwise prepared to take the field immediately. He afterward decided that the proper response was not merely for the capture of Multan, but also the entire subjugation of the Punjab.[2] He therefore resolutely delayed to strike, organized a strong army for operations in November, and himself proceeded to the Punjab. With evidence that the revolt was spreading outwards, Dalhousie declared, "Unwarned by precedent, uninfluenced by example, the Sikh nation has called for war; and on my words, sirs, war they shall have and with a vengeance."[9]

Despite the successes gained by Herbert Edwardes in the Second Anglo-Sikh War with Mulraj, and Gough's indecisive victories at Ramnagar in November, at Sadulpur in December, and at Chillianwala in the following month, the stubborn resistance at Multan showed that the task required the utmost resources of the government. At length, on 22 January 1849, the Multan fortress was taken by General Whish, who was thus set at liberty to join Gough at Gujarat. Here a complete victory was won on 21 February at the Battle of Gujrat, the Sikh army surrendered at Rawalpindi, and their Afghan allies were chased out of India. In spite of substantial attempts by Sikh and Muslim forces to polarize opposition through religious and anti-British sentiment, Dalhousie's military commanders were able to maintain the loyalty of troops, with the exception of a small number of Gurkah deserters.[10] For his services the Earl of Dalhousie received the thanks of the Parliament and a step in the peerage, as Marquess.

The war being now over, Dalhousie, without specific instructions from his superiors, annexed the Punjab. Believing in inherent superiority of British rule over the "archaic" Indian system of rule, Dalhousie attempted to dismantle local rule, fulfilling the imperial goals of the Anglicizer Lord Bentinck. However, the province quickly became ruled by a group of "audacious, eccentric, and often Evangelical pioneers".[11] In an attempt to minimize further conflict, he removed a number of these officials, establishing what he believed to be a more logical and rational system in which the Punjab was systematically divided into districts and divisions, governed by District officers and Commissioners respectively. This lasting system of rule established governance through a young maharaja under a triumvirate of the Governor General.[2]

Governance under the established "Punjab School" of Henry and John Lawrence was initially successful, partially due to the system of local cultural respect, while still maintaining British values against acts of widow burning, female infanticide, and burning of lepers alive by small segments of the Indian populace.[12] However, Punjabi rule eventually came to be seen as despotic, largely because of the expansion of judicial system. Although often unpredictable or despotic, many Indians in "rationalized" provinces preferred their previous native rule.

Second Burmese War

One further addition to the empire was made by conquest. The Burmese court at Ava was bound by the Treaty of Yandaboo, 1826, to protect British ships in Burmese waters.[2] But there arose a dispute between the Governor of Rangoon and certain British shipping interests (the Monarch and the Champion).

The facts of the event were obscured by conflicts between colonial administrators reporting to the admirals of the navy, rather than the company or civil authorities. The nature of the dispute was mis-represented to Parliament, and Parliament played a role in further "suppressing" the facts released to the public, but most of the facts were established by comparative reading of these conflicting accounts in what was originally an anonymous pamphlet, How Wars are Got Up in India; this account by Richard Cobden remains almost the sole contemporaneous account of who actually made the decision to invade and annex Burma.[13]

In defending the pretext for invasion after the fact, Dalhousie quoted the maxim of Lord Wellesley that any insult offered to the British flag at the mouth of the Ganges should be resented as promptly and fully as an insult offered at the mouth of the Thames.[2] Attempts were made to solve the dispute by diplomacy. The Burmese eventually removed the Governor of Rangoon but this not considered sufficient. Commodore Lambert, despatched personally by Dalhousie, deliberately provoked an incident and then announced a war.

The Burmese Kingdom offered little in the way of resistance. Martaban was taken on 5 April 1852, and Rangoon and Bassein shortly afterwards. Since, however, the court of Ava was unwilling to surrender half the country in the name of "peace", the second campaign opened in October, and after the capture of Prome and Pegu the annexation of the province of Pegu was declared by a proclamation dated 20 December 1853.[2] To any further invasion of the Burmese empire Dalhousie was firmly opposed, being content to cut off Burma's commercial and political access to the outside world by the annexation. Some strangely spoke of the war as "uniting" territory, but in practice Arakan, Tenasserim and the new territories were still only linked in practical terms by sea.

By what his supporters considered wise policy he attempted to pacify the new province, placing Colonel Arthur Phayre in sole charge of it, personally visiting it, and establishing a system of telegraphs and communications.[2] In practice, the new province was in language and culture very different from India. It could never successfully integrate into the Indian system. The end result of the war was to add an expensive new military and political dependency which did not generate sufficient taxes to pay for itself.[2] British Indian rule of Arakan and Tenasserim had been a financial disaster for the Indian Administration. Multiple times in the 1830s questions were raised about getting rid of these territories altogether. Why Dalhousie was so obsessed with increasing the size of a territory that did not generate sufficient revenue to pay for its own administration has never been explained.

One consequential factor of this war was Dalhousie's continuation of the requirement that Sepoys be forced to serve abroad. This created great discontent among Indian sepoys, because it violated the Hindu religious prohibition against travel. In fact, this resulted in the mutiny of several regiments in the Punjab.[14] When this belief that the British were intentionally forcing caste breaking was combined with the widespread belief that the British were intentionally violating Hindu and Muslim purity laws with their new greased cartridges, the consequences (culminating in 1857), would prove to be extremely destructive.[15]

Policies of reforms

Doctrine of Lapse

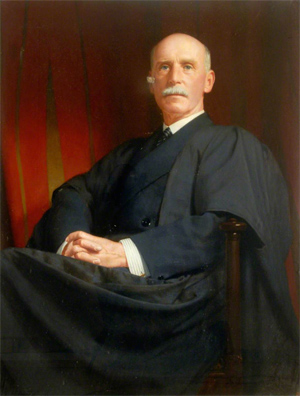

Portrait of Lord Dalhousie by John Watson-Gordon, 1847.

Main article: Doctrine of Lapse

The most controversial and tainted 'reform' developed and implemented under Dalhousie was the policy of taking all legal (often illegal too) means possible to assume control over "lapsed" states. Dalhousie, driven by the conviction that all India needed to be brought under British administration, began to apply what was called the doctrine of lapse. Under the doctrine, the British annexed any non-British state where there was a lack of a proper male lineal heir. Under the policy he recommended the annexation of Satara in January 1849, of Jaitpur and Sambalpur in the same year, and of Jhansi and Nagpur in 1853. In these cases his action was approved by the home authorities, but his proposal to annex Karauli in 1849 was disallowed, while Baghat and the petty estate of Udaipur, which he had annexed in 1851 and 1852 respectively, were afterwards restored to native rule. These annexations are considered by critics to generally represent an uneconomic drain on the financial resources of the company in India.

Educational reforms

Dalhousie had a strong personal commitment to the establishment of a national system of education in India. He ensured the successful administration of the provisions contained in the 1854 dispatch.[16]

Dalhousie declared that no single change was likely to produce more important and beneficial consequences than female education. The Educational dispatch of 1854 favored Women's education. There was shift in government policy under him from higher education for elite towards mass education for both .[17] He along with Bethune are credited with changing policy in favour of Women's education. Dalhousie even personally supported the Bethune Women school from his own money set up by Bethune after his death.[18] Before he left for England he took personal interest and introduced the Hindu Widows' Remarriage Act, 1856, permitting widow remarriage which became an act after being approved by his successor, Lord Canning .[19][20][21][22]

Development of infrastructure

Other measures with the same object were carried out in the Company's own territories. Bengal, long ruled by the Governor-General or his delegate, was placed under its own Lieutenant-Governor in May 1854. The military boards were swept away; selection took the place of seniority in the higher commands; an army clothing and a stud department were created, and the medical service underwent complete reorganization. A department of public works was established in each presidency, and engineering colleges were provided. An imperial system of telegraphs followed. The first link of railway communication was completed in 1855, and well-considered plans mapped out the course of other lines and their method of administration. Dalhousie encouraged private enterprise to develop railways in India for the good of the people and also to reduce absolute dependence on the government. However, as an authoritarian, utilitarian ruler, Dalhousie brought the railways under state control-attempting to bring the greatest benefit to India from the expanding network.[citation needed]

In addition, the Ganges Canal was completed; and despite the cost of wars in the Punjab and Burma, liberal provision was made for metalled roads and bridges.[23] The construction of massive irrigation works such as the 350-mile Ganges Canal, which contains thousands of miles of distributaries was a substantial project that was particularly beneficial for the largely agricultural India. In spite of damaging certain areas of farmland by increasing soil salinity, overall the individuals living along the canal were noticeably better fed and clothed than those who were not.[24] Increasing irrigated area resulted in increase in population. Reforms to improve the condition of the increased population such as immunization and establishment of educational institutions were never implemented. This kept the population poor and bonded to agricultural activities promoting bonded labour. Europeanization and consolidation of authority were the keynote of his policy. In nine minutes he suggested means for strengthening the Company's European forces, calling attention to the dangers that threatened the British community, a handful of scattered strangers; but beyond the additional powers of recruitment which at his entreaty were granted in the last charter act of 1853, his proposals were shelved by the home authorities as they represented yet more expense added to the cost of India. In his administration Dalhousie vigorously asserted his control over even minor military affairs, and when Sir Charles Napier ordered certain allowances, given as compensation for the dearness of provisions, to be granted to the sepoys on a system which had not been sanctioned from headquarters, and threatened to repeat the offence, the Governor-General rebuked him to such a degree that Napier resigned his command.

Dalhousie's reforms were not confined to the departments of public works and military affairs. He created an imperial system of post-offices, reducing the rates of carrying letters and introducing postage stamps. He created the department of public instruction; he improved the system of inspection of goals, abolishing the practice of branding convicts; freed converts to other religions from the loss of their civil rights; inaugurated the system of administrative reports; and enlarged the Legislative Council of India. His wide interest in everything that concerned the welfare of British economic interests in the country was shown in the encouragement he gave to the culture of tea, in his protection of forests, in the preservation of ancient and historic monuments. With the object of making the civil administration more European, he closed what he considered to be the useless college in Calcutta for the education of young civilians, establishing in its place a European system of training them in mufasal stations, and subjecting them to departmental examinations. He was equally careful of the well-being of the European soldier, providing him with healthy recreations and public gardens.

Civil Service reform

To the civil service he gave improved leave and pension rules, while he purified its moral by forbidding all share in trading concerns, by vigorously punishing insolvents, and by his personal example of careful selection in the matter of patronage. No Governor-General ever penned a larger number of weighty papers dealing with public affairs in India. Even after laying down office and while on his way home, he forced himself, ill as he was, to review his own administration in a document of such importance that the House of Commons gave orders for its being printed (Blue Book 245 of 1856). Another consequential set of reforms, were those aimed at modernizing the land tenure and revenue system. Throughout his time in office, Dalhousie disposed large landowners from portions of their estates. He also implemented policies attempting to end the rule of the zamindar tax farmers, as he viewed them as destructive "drones of the soil".[25] However, thousands of smaller landlords had their holdings completely removed as did the relatively poor who leased small parcels of their land while farming the rest. This was particularly significant as the sepoys were often recruited from these economic groups.[26] He introduced a system of open competition as the basis of recruitment for civil servants of the company and thus deprived the Directors of their patronage system under Government of India Act 1853.[27]

Foreign policy

His foreign policy was guided by a desire to reduce the nominal independence of the larger native states, and to avoid extending the political relations of his government with foreign powers outside India. Pressed to intervene in Hyderabad, he refused to do so, claiming on this occasion that interference was only justified if the administration of native princes tends unquestionably to the injury of the subjects or of the allies of the British government. He negotiated in 1853 a treaty with the nizam, which provided funds for the maintenance of the contingent kept up by the British in support of that princes' authority, by the assignment of the Berars in lieu of annual payments of the cost and large outstanding arrears. The Berar treaty, he told Sir Charles Wood, is more likely to keep the nizam on his throne than anything that has happened for 50 years to him, while at the same time the control thus acquired over a strip of territory intervening between Bombay and Nagpur promoted his policy of consolidation and his schemes of railway extension. The same spirit induced him to tolerate a war of succession in Bahawalpur, so long as the contending candidates did not violate British territory.

He refrained from punishing Dost Mohammad for the part he had taken in the Sikh War, and resolutely to refuse to enter upon any negotiations until the amir himself came forward. Then he steered a middle course between the proposals of his own agent, Herbert Edwardes, who advocated an offensive alliance, and those of John Lawrence, who would have avoided any sort of engagement. He himself drafted the short treaty of peace and friendship which Lawrence signed in 1855, that officer receiving in 1856 the Order of the Bath as a Knight Commander in acknowledgement of his services in the matter. While, however, Dalhousie was content with a mutual engagement with the Afghan chief, binding each party to respect the territories of the other, he saw that a larger measure of interference was needed in Baluchistan, and with the Khan of Kalat he authorized Major Jacob to negotiate a treaty of subordinate co-operation on 14 May 1854.

The khan was guaranteed an annual subsidy of Rs. 50,000, in return for the treaty which bound him to the British wholly and exclusively. To this the home authorities demurred, but the engagement was duly ratified, and the subsidy was largely increased by Dalhousies successors. On the other hand, he insisted on leaving all matters concerning Persia and Central Asia to the decision of the queen's advisers. After the conquest of the Punjab, he began the expensive process of attempting to police and control the Northwest Frontier region. The hillmen, he wrote, regard the plains as their food and prey, and the Afridis, Mohmands, Black Mountain tribes, Waziris and others had to be taught that their new neighbours would not tolerate outrages. But he proclaimed to one and all his desire for peace, and urged upon them the duty of tribal responsibility. Nevertheless, the military engagement on the northwest frontier of India he began grew yearly in cost and continued without pause until the British left Pakistan.

The annexation of Oudh was reserved to the last. The home authorities had asked Dalhousie to prolong his tenure of office during the Crimean War, but the difficulties of the problem no less than complications elsewhere had induced him to delay operations. In 1854 he appointed Outram as resident at the court of Lucknow, directing him to submit a report on the condition of the province. This was furnished in March 1855. The report provided the British an excuse for action based on "disorder and misrule". Dalhousie, looking at the treaty of 1801, decided that he could do as he wished with Oudh as long as he had the king's consent. He then demanded a transfer to the Company of the entire administration of Oudh, the king merely retaining his royal rank, certain privileges in the courts, and a liberal allowance. If he should refuse this arrangement, a general rising would be arranged, and then the British government would intervene on its own terms.

On 21 November 1855, the court of directors instructed Dalhousie to assume the control of Oudh, and to give the king no option unless he was sure that his majesty would surrender the administration rather than risk a revolution. Dalhousie was in bad health and on the eve of retirement when the belated orders reached him; but he at once laid down instructions for Outram in every detail, moved up troops, and elaborated a scheme of government with particular orders as to conciliating local opinion. The king refused to sign the ultimatum (in the form of a "treaty") put before him, and a proclamation annexing the province was therefore issued on 13 February 1856.

In his mind, only one important matter now remained to him before quitting office. The insurrection of the Kolarian Santals of Bengal against the extortions of landlords and moneylenders had been severely repressed, but the causes of the insurrection had still to be reviewed and a remedy provided. By removing the tract of country from local rule, enforcing the residence of British officers there, and employing the Santal headmen in a local police, he created a system of administration which proved successful in maintaining order.

Return to Britain

A length, after seven years of strenuous labour, Dalhousie, on the 6th of March 1856, set sail for England on board the Company's " Firoze," an object of general sympathy and not less general respect. At Alexandria he was carried by H.M.S. " Caradoc " to Malta, and thence by the " Tribune " to Spithead, which he reached on the 13th of May. His return had been eagerly looked for by statesmen who hoped that he would resume his public career, by the Company which voted him an annual pension of £5,000 (£1.5 million in 2009), and by the queen who earnestly prayed for the blessing of restored health and strength; conversely, the outbreak of the "Sepoy Mutiny" led to bitter attacks on the record of his policy, and to widespread criticisms (both fair and unfair) of his political interests and career. His health deteriorated in Malta and at Malvern, Edinburgh, where he sought medical treatment. In his correspondence and public statements, he was careful not to assign blame or cause embarrassment to colleagues in government. During this period, John Lawrence, 1st Baron Lawrence invoked his counsel and influence. By his last wish, his private journal and papers of personal interest were sealed against publication or inquiry for fully 50 years after his death.

Established in 1854 by the British Empire in India as a summer retreat for its troops and bureaucrats, the hill station of Dalhousie was named after Lord Dalhousie who was Governor-General of India at that time.

References

1. Ghosh, Suresh Chandra (1978). "The Utilitarianism of Dalhousie and the Material Improvement of India". Modern Asian Studies. 12 (1): 97–110. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00008167. JSTOR 311824.

2. Lee-Warner, William (1911). "Dalhousie, James Andrew Broun Ramsay, 1st Marquess of" . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

3. Lee-Warner, Sir William, The Life of the Marquess of Dalhousie, London, 1904, vol.1: 3

4. Tyerman, Christopher (2000). "A History of Harrow School, 1324-1991". Oxford University Press. p. 202. ISBN 9780198227960. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

5. "Captains of Deal Castle". East Kent freeuk. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

6. Christopher Hibbert, The Great Mutiny: India 1857 (New York, NY: The Viking Press, 1978), p. 25

7. D. R. SarDesai, India: The Definitive History (Los Angeles: Westview Press, 2008), p. 238.

8. Suresh Chandra Ghosh, "The Utilitarianism of Dalhousie and the Material Improvement of India." Modern Asian Studies; Vol. 12 no. 1 (1978), 97-110. online

9. James, Lawrence. Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), 115

10. James, Lawrence. Raj: The Making and Unmaking of British India (New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), 116

11. Gilmour, David. The Ruling Caste: Imperial Lives in the Victorian Raj New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005, 161

12. Gilmour, 163.

13. This text went through several "editions" rapidly, with the third edition already in print in 1853 (this was subsequently reprinted in The Political Writings of Richard Cobden, vol. 2). The full text is now available as a book digitized by Google: Richard Cobden (1853). How Wars are Got Up in India: The Origin of the Burmese War. W. & F. G. Cash.

14. Vohra, Ranbir. The Making of India: A Historical Survey. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1997, 79.

15. Hibbert, 61.

16. Suresh Chandra Ghosh, "Dalhousie, Charles Wood and the Education Despatch of 1854." History of Education 4.2 (1975): 37-47.

17. Geraldine Hancock Forbes (1999). Women in Modern India. The New Cambridge History of India. IV.2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-521-65377-0.

18. Gouri Srivastava (2000). Women's Higher Education in the 19th Century. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 65–67. ISBN 978-81-7022-823-3.

19. B. R. Sunthankar (1988). Nineteenth Century History of Maharashtra: 1818-1857. Shubhada-Saraswat Prakashan. p. 184. ISBN 978-81-85239-50-7.

20. Suresh Chandra Ghosh (1975). Dalhousie in India, 1848-56: A Study of His Social Policy as Governor-General. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. pp. 54–55. OCLC 2122938.

21. John F. Riddick (2006). The History of British India: A Chronology. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-313-32280-8.

22. Chandrakala Anandrao Hate (1948). Hindu Woman and Her Future. New Book Company. p. 176. OCLC 27453034.

23. Digital South Asia Library. Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 2. University of Chicago. http://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/gaze ... 02_539.gif (accessed 14 April 2009).

24. Gilmour, 9.

25. Brendon, Piers. The Decline and Fall of the British Empire: 1781–1997. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2008.

26. Hibbert, 49.

27. M. Lakshmikanth, Public Administration, TMH, Tenth Reprint, 2013

• This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Dalhousie, James Andrew Broun Ramsay, 1st Marquess of". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

• "Ramsay, James Andrew Broun". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23088. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

• Arnold, Sir Edwin (1865). The Marquis of Dalhousie's Administration of British India: Annexation of Pegu, Nagpor, and Oudh, and a General Review of Lord Dalhousie's Rule. Saunders, Otley, and Company.

• Campbell, George Douglas (Duke of Argyll ) (1865). India under Dalhousie and Canning. Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green.

• Ghosh, Suresh Chandra. (2013) The History of Education in Modern India, 1757-2012 (4th ed.) pp 65–84.

• Ghosh, Suresh Chandra. (1978) "The utilitarianism of Dalhousie and the material improvement of India." Modern Asian Studies[ 12.1 (1978): 97-110 online.

• Ghosh, Suresh Chandra. Dalhousie in India, 1848-56: A Study of His Social Policy as Governor-General (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 1975).

• Gorman, Mel. (1971) "Sir William O'Shaughnessy, Lord Dalhousie, and the establishment of the telegraph system in India." Technology and Culture 12.4 (1971): 581-601 online.

• Hunter, Sir William Wilson (1894). The Marquess of Dalhousie and the Final Development of the Company's Rule. Rulers of India series. Clarendon Press.

• Lee-Warner, Sir William (1904). The life of the Marquis of Dalhousie, K. T. Macmillan and Co.

• Trotter, Lionel James (1889). Life of the Marquis of Dalhousie. Hard Press. ISBN 978-1-4077-4948-8.

External links

• Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by the Marquess of Dalhousie