Mahabharata

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/17/21

Highlights:

Vishnu Sukthankar, editor of the first great critical edition of the Mahābhārata, commented: "It is useless to think of reconstructing a fluid text in an original shape, based on an archetype and a stemma codicum. What then is possible? Our objective can only be to reconstruct the oldest form of the text which it is possible to reach based on the manuscript material available." That manuscript evidence is somewhat late, given its material composition and the climate of India.

-- Mahabharata, by Wikipedia

I have a larger vision or fantasy of original Indian Buddhism as an ocean with many icebergs, each representing the local textual traditions...of the different parts of the Indian world. Those icebergs are mostly gone...We have the Pali canon...the partial Sanskrit canon...They had a common core but they had many different texts in and around that basic commonality... and... there's no hope of finding them mainly for a simple physical reason, the climate of...India proper is such that organic materials...never last for more than a few hundred years. There are really no really old manuscripts in India proper. You only get the ancient manuscripts from the borderlands of India, in this case Gandhara which has a more moderate climate.

-- One Buddha, 15 Buddhas, 1,000 Buddhas, by Richard Salomon

Mahabharata

महाभारतम्

Mahabharata

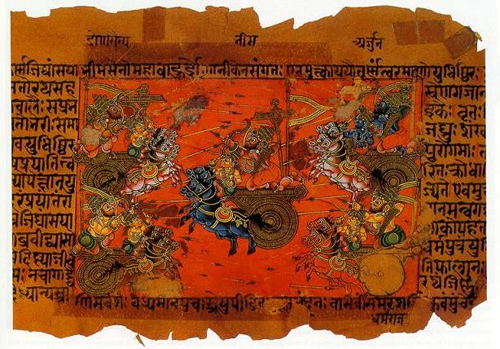

Manuscript illustration of the Battle of Kurukshetra

Information

Religion: Hinduism

Author: Vyasa

Language: Sanskrit

Verses: 200,000

The Mahābhārata (US: /məhɑːˈbɑːrətə/,[1] UK: /ˌmɑːhəˈbɑːrətə/;[2] Sanskrit: महाभारतम्, Mahābhāratam, pronounced [mɐɦaːˈbʱaːrɐtɐm]) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India, the other being the Rāmāyaṇa.[3] It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the Kurukshetra War and the fates of the Kaurava and the Pāṇḍava princes and their successors.

The Kurukshetra War, also called the Mahabharata War, is a war described in the Indian epic poem Mahābhārata. The conflict arose from a dynastic succession struggle between two groups of cousins, the Kauravas and Pandavas, for the throne of Hastinapura. It involved several ancient kingdoms participating as allies of the rival groups.

The historicity of the war remains subject to scholarly discussions. It is possible that the Battle of the Ten Kings, mentioned in the Rigveda, may have "formed the 'nucleus' of the story" of the Kurukshetra war, though it was greatly expanded and modified in the Mahabharata's account, making the Mahabharata's version of very dubious historicity. Attempts have been made to assign a historical date to the Kurukshetra War. Scholarly research suggests ca. 1000 BCE, while popular tradition holds that the war marks the transition to Kali Yuga and thus dates it to 3102 BCE.

The location of the battle is described as having occurred in Kurukshetra in North India. Despite only spanning eighteen days, the war narrative forms more than a quarter of the book, suggesting its relative importance within the entire epic, which spans decades of the warring families. The narrative describes individual battles and deaths of various heroes of both sides, military formations, war diplomacy, meetings and discussions among the characters, and the weapons used. The chapters (parvas) dealing with the war are considered amongst the oldest in the entire Mahābhārata.

-- Kurukshetra War, by Wikipedia

It also contains philosophical and devotional material, such as a discussion of the four "goals of life" or puruṣārtha (12.161). Among the principal works and stories in the Mahābhārata are the Bhagavad Gita, the story of Damayanti, the story of Savitri and Satyavan, the story of Kacha and Devyani, the story of Ṛṣyasringa and an abbreviated version of the Rāmāyaṇa, often considered as works in their own right.

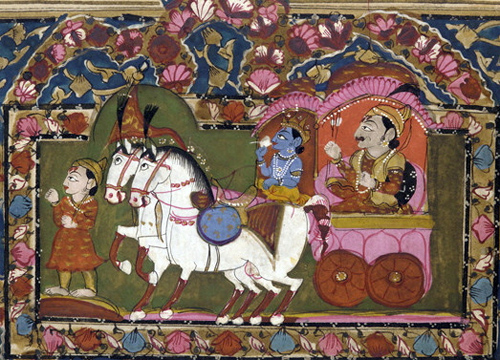

Krishna and Arjuna at Kurukshetra, 18th–19th-century painting

Traditionally, the authorship of the Mahābhārata is attributed to Vyāsa. There have been many attempts to unravel its historical growth and compositional layers. The bulk of the Mahābhārata was probably compiled between the 3rd century BCE and the 3rd century CE, with the oldest preserved parts not much older than around 400 BCE.[4][5] The original events related by the epic probably fall between the 9th and 8th centuries BCE.[5] The text probably reached its final form by the early Gupta period (c. 4th century CE).[6][7]

The Mahābhārata is the longest epic poem known and has been described as "the longest poem ever written".[8][9] Its longest version consists of over 100,000 śloka or over 200,000 individual verse lines (each shloka is a couplet), and long prose passages. At about 1.8 million words in total, the Mahābhārata is roughly ten times the length of the Iliad and the Odyssey combined, or about four times the length of the Rāmāyaṇa.[10][11] W. J. Johnson has compared the importance of the Mahābhārata in the context of world civilization to that of the Bible, the Quran, the works of Homer, Greek drama, or the works of William Shakespeare.[12] Within the Indian tradition it is sometimes called the fifth Veda.[13]

Textual history and structure

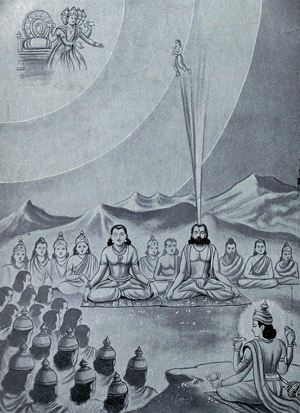

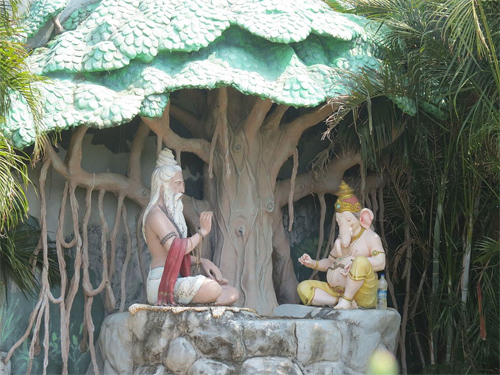

Modern depiction of Vyasa narrating the Mahābhārata to Ganesha at the Murudeshwara temple, Karnataka.

The epic is traditionally ascribed to the sage Vyāsa, who is also a major character in the epic. Vyāsa described it as being itihāsa (Sanskrit: इतिहास, meaning "history"). He also describes the Guru-shishya parampara, which traces all great teachers and their students of the Vedic times.

Vyasa is considered one of the seven Chiranjivis (long-lived, or immortals), who are still in existence according to Hindu tradition.

Vyasa is believed to be an expansion of the God Vishnu, who came in Dvapara Yuga to make all the Vedic knowledge from oral tradition available in written form...

The Vishnu Purana (Book 3, Ch 3) says:In every third world age (Dvapara), Vishnu, in the person of Vyasa, in order to promote the good of mankind, divides the Veda, which is properly but one, into many portions. Observing the limited perseverance, energy and application of mortals, he makes the Veda fourfold, to adapt it to their capacities; and the bodily form which he assumes, in order to effect that classification, is known by the name of Veda-Vyasa. Of the different Vyasas in the present Manvantara and the branches which they have taught, you shall have an account. Twenty-eight times have the Vedas been arranged by the great Rishis in the Vaivasvata Manvantara... and consequently, eight and twenty Vyasa's have passed away; by whom, in the respective periods, the Veda has been divided into four. The first... distribution was made by Svayambhu (Brahma) himself; in the second, the arranger of the Veda (Vyasa) was Prajapati... (and so on up to twenty-eight)...

Vyasa is traditionally known as the chronicler of this epic and also features as an important character in Mahābhārata, Vyasa asks Ganesha to assist him in writing the text. Ganesha imposes a precondition that he would do so only if Vyasa would narrate the story without a pause. Vyasa set a counter-condition that Ganesha understands the verses first before transcribing them. Thus Vyasa narrated the entire Mahābhārata and all the Upanishads and the 18 Puranas, while Lord Ganesha wrote...

Vyasa is also credited with the writing of the eighteen major Purāṇas, which are works of Indian literature that cover an encyclopedic range of topics covering various scriptures. His son Shuka narrates the Bhagavata Purana to Arjuna's grandson Parikshit...

There may have been more than one Vyasa, or the name Vyasa may have been used at times to give credibility to a number of ancient texts.

-- Vyasa, by Wikipedia

The first section of the Mahābhārata states that it was Ganesha who wrote down the text to Vyasa's dictation. Though this is regarded as an interpolation to the epic by the scholars. The "Critical Edition" doesn't include Ganesha at all.[14]

The epic employs the story within a story structure, otherwise known as frametales, popular in many Indian religious and non-religious works. It is first recited at Takshashila by the sage Vaiśampāyana,[15][16] a disciple of Vyāsa, to the King Janamejaya who was the great-grandson of the Pāṇḍava prince Arjuna. The story is then recited again by a professional storyteller named Ugraśrava Sauti, many years later, to an assemblage of sages performing the 12-year sacrifice for the king Saunaka Kulapati in the Naimiśa Forest.

Sauti recites the slokas of the Mahabharata.

The text was described by some early 20th-century Indologists as unstructured and chaotic. Hermann Oldenberg supposed that the original poem must once have carried an immense "tragic force" but dismissed the full text as a "horrible chaos."[17] Moritz Winternitz (Geschichte der indischen Literatur 1909) considered that "only unpoetical theologists and clumsy scribes" could have lumped the parts of disparate origin into an unordered whole.[18]

Accretion and redaction

Research on the Mahābhārata has put an enormous effort into recognizing and dating layers within the text. Some elements of the present Mahābhārata can be traced back to Vedic times.[19] The background to the Mahābhārata suggests the origin of the epic occurs "after the very early Vedic period" and before "the first Indian 'empire' was to rise in the third century B.C." That this is "a date not too far removed from the 8th or 9th century B.C."[5][20] is likely. Mahābhārata started as an orally-transmitted tale of the charioteer bards.[21] It is generally agreed that "Unlike the Vedas, which have to be preserved letter-perfect, the epic was a popular work whose reciters would inevitably conform to changes in language and style,"[20] so the earliest 'surviving' components of this dynamic text are believed to be no older than the earliest 'external' references we have to the epic, which may include an allusion in Panini's 4th century BCE grammar Aṣṭādhyāyī 4:2:56.[5][20] It is estimated that the Sanskrit text probably reached something of a "final form" by the early Gupta period (about the 4th century CE).[20] Vishnu Sukthankar, editor of the first great critical edition of the Mahābhārata, commented: "It is useless to think of reconstructing a fluid text in an original shape, based on an archetype and a stemma codicum. What then is possible? Our objective can only be to reconstruct the oldest form of the text which it is possible to reach based on the manuscript material available."[22] That manuscript evidence is somewhat late, given its material composition and the climate of India, but it is very extensive.

I have a larger vision or fantasy of original Indian Buddhism as an ocean with many icebergs, each representing the local textual traditions...of the different parts of the Indian world. Those icebergs are mostly gone...We have the Pali canon...the partial Sanskrit canon...They had a common core but they had many different texts in and around that basic commonality... and... there's no hope of finding them mainly for a simple physical reason, the climate of...India proper is such that organic materials...never last for more than a few hundred years. There are really no really old manuscripts in India proper. You only get the ancient manuscripts from the borderlands of India, in this case Gandhara which has a more moderate climate.

-- One Buddha, 15 Buddhas, 1,000 Buddhas, by Richard Salomon

The Mahābhārata itself (1.1.61) distinguishes a core portion of 24,000 verses: the Bhārata proper, as opposed to additional secondary material, while the Aśvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra (3.4.4) makes a similar distinction. At least three redactions of the text are commonly recognized: Jaya (Victory) with 8,800 verses attributed to Vyāsa, Bhārata with 24,000 verses as recited by Vaiśampāyana, and finally the Mahābhārata as recited by Ugraśrava Sauti with over 100,000 verses.[23][24] However, some scholars, such as John Brockington, argue that Jaya and Bharata refer to the same text, and ascribe the theory of Jaya with 8,800 verses to a misreading of a verse in Ādiparvan (1.1.81).[25] The redaction of this large body of text was carried out after formal principles, emphasizing the numbers 18[26] and 12. The addition of the latest parts may be dated by the absence of the Anuśāsana-Parva and the Virāta Parva from the "Spitzer manuscript".[27] The oldest surviving Sanskrit text dates to the Kushan Period (200 CE).[28]

re·dac·tion: the process of editing text for publication.

"what was left after the redaction would be virtually useless"

the censoring or obscuring of part of a text for legal or security purposes.

a version of a text, such as a new edition or an abridged version.

"the author himself never chose to establish a definitive redaction"

According to what one character says at Mbh. 1.1.50, there were three versions of the epic, beginning with Manu (1.1.27), Astika (1.3, sub-Parva 5), or Vasu (1.57), respectively. These versions would correspond to the addition of one and then another 'frame' settings of dialogues. The Vasu version would omit the frame settings and begin with the account of the birth of Vyasa. The astika version would add the sarpasattra and aśvamedha material from Brahmanical literature, introduce the name Mahābhārata, and identify Vyāsa as the work's author. The redactors of these additions were probably Pāñcarātrin scholars who according to Oberlies (1998) likely retained control over the text until its final redaction. Mention of the Huna in the Bhīṣma-Parva however appears to imply that this Parva may have been edited around the 4th century.[29]

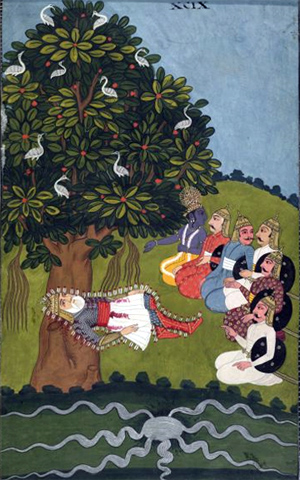

The snake sacrifice of Janamejaya

The Ādi-Parva includes the snake sacrifice (sarpasattra) of Janamejaya, explaining its motivation, detailing why all snakes in existence were intended to be destroyed, and why despite this, there are still snakes in existence. This sarpasattra material was often considered an independent tale added to a version of the Mahābhārata by "thematic attraction" (Minkowski 1991), and considered to have a particularly close connection to Vedic (Brahmana) literature. The Pañcavimśa Brahmana (at 25.15.3) enumerates the officiant priests of a sarpasattra among whom the names Dhṛtarāṣtra and Janamejaya, two main characters of the Mahābhārata's sarpasattra, as well as Takṣaka, the name of a snake in the Mahābhārata, occur.[30]

The Suparṇākhyāna, a late Vedic period poem considered to be among the "earliest traces of epic poetry in India," is an older, shorter precursor to the expanded legend of Garuda that is included in the Āstīka Parva, within the Ādi Parva of the Mahābhārata.[31][32]

The Adi Parva or The Book of the Beginning is the first of eighteen books of the Mahabharata. "Adi" (आदि, Ādi) is a Sanskrit word that means "first".

Adi Parva traditionally has 19 sub-books and 236 adhyayas (chapters). The critical edition of Adi Parva has 19 sub-books and 225 chapters.

Adi Parva describes how the epic came to be recited by Ugrasrava Sauti to the assembled rishis at the Naimisha Forest after first having been narrated at the sarpasatra of Janamejaya by Vaishampayana at Taxila. It includes an outline of contents from the eighteen books, along with the book's significance. The history of the Bhāratas and the Bhrigus are described. The main part of the work covers the birth and early life of the princes of the Kuru Kingdom and the persecution of the Pandavas by Dhritarashtra.

Structure & Chapters

The Adi Parva consists of 19 upa-parvas or sub-books (also referred to as little books). Each sub-book is also called a parva and is further subdivided into chapters, for a total of 236 chapters in Adi Parva. The following are the sub-parvas:[5]

1. Anukramanika Parva (Chapter: 1) Sauti meets the Rishis led by Shaunaka in Naimisha Forest. They express a desire to hear Mahabharata. He explains the stories of creation to them. He narrates the story of how the Mahabharata was written. This parva describes the significance of Mahabharata, claims comprehensive synthesis of all human knowledge, and why it must be studied.

2. Sangraha Parva (Chapter: 2) Story of Samantha Panchaka. Definition of Akshauhini in an army. Outline of contents of 18 books of Mahabharata.

3. Paushya Parva (Chapter: 3) Story of Sarama's curse on Janamejaya, of Aruni, Upamanyu and Veda (The disciples of Sage Dhaumya) and of Uttanka, Paushya and sage Veda.

4. Pauloma Parva (Chapters: 4–12) History of the Bhargava race of men. Story of Chyavana's birth.

5. Astika Parva (Chapters: 13–58) Story of the Churning of the Ocean. Theories on dharma, worldly bondage and release. Story of the Sarpa Satra including Janamejaya's vow to kill all snakes, step to annihilate them with a sacrificial fire, decision to apply Ahimsa (non-violence) to snakes and all life forms. Story of birth of Astika. Story of how Vaishampayana came to narrate the Mahabharata to Janamejaya.

6. Adivansavatarana Parva a.k.a. Anshavatarana Parva (Chapters: 59–64) History of Pandava and Kuru princes. Stories of Shantanu, Bhishma and Satyavati. Stories of Karna's birth, Lord Krishna's birth and of and Animandavya. Appeal to Brahma that the gods should reincarnate to save the chaos that earth has become.

7. Sambhava Parva (Chapters: 65–142) Theory of life on earth and of gods. Story of Dronacharya, Kripacharya and other sages. Story of Dushyanta and Shakuntala. Story of Bharata's birth. Sakuntala goes to Dushyanta with the boy. He first refuses to remember her and their marriage but later apologizes and accepts. Bharata becomes prince. Stories of Yayati, Devayani and Sharmishtha. Stories of Yadu, Puru and the Paurava race of men. The Pandava brothers retreat into the forest, chased by Dhritarashtra. The stories the Swayamvara of Kunti, marriage of Madri and marriage of Vidura. Attempts to reconcile the conflict between Kauravas and Pandavas.

8. Jatugriha Parva a.k.a. Jatugriha-daha Parva (Chapters: 143–153) Kanika counsels Dhritarashtra on how to rule a kingdom and on how deception is an effective tool for governance and war, against enemies and potential competition. Kanika narrates his symbolic tale about jackal, tiger, mouse, mongoose and deer and he advises that a weak ruler should ignore his own weaknesses and focus on other people's weakness and pretend to be friends while being cruel and destructive to others, particularly when the competition is good and stronger. Dhritarashtra schemes to build a home for Pandavas in the forest, from lacquer and other inflammable materials as a friendly gesture, but with plans to burn them alive on the darkest night. Kanika's theory is called wicked and evil by Vidura, a sage of true knowledge and the good, who is also the advisor and friend to Pandavas. Vidura and Pandavas plan escape by building a tunnel inside the inflammable house. The fire is lit and the Pandavas escape. Dhritarashtra falsely believes Pandavas are dead. Duryodhana is pleased and sets on ruling the kingdom.

9. Hidimva-vadha Parva (Chapters: 154–158) The story of the wanderings of Pandava brothers after the escape from the fire. Story of Bhima and the Rakshashi Hidimba. She falls in love with Bhima and refuses to help her brother. The story of the battle between Bhima and Hidimba's demon brother, Hidimbasur, showing the enormous strength of the giant brother Bhima. Bhima and Hidimba have a son named Ghatotkacha.

10. Vaka-vadha Parva a.k.a. Baka-vadha Parva (Chapters: 159–166) The life of Pandavas brothers in Ekachakra. Story about Bhima slaying another demon Bakasura, who has been terrorizing people of Ekachakra. Heroine of Mahabharata, Draupadi, is born in holy fire. Word spreads that the Pandavas may be alive.

11. Chaitraratha Parva (Chapters: 167–185) Pandavas set out for Panchala. Arjuna fights with a Gandharva. Stories of Tapati and the conflict between Vashistha and Vishwamitra. Stories of Kalmashapada, Parashara and Aurva. Dehumanization and persecution of Bhargava race of men.

12. Swayamvara Parva (Chapters: 186–194) The Pandavas arrive in Panchala. Draupadi's swayamvara. The Pandavas arrive at the swayamvara in disguise of Brahmanas. Arjuna excels in the swayamvara and wins Draupadi's heart and hand. Krishna recognizes the individuals in disguise as the Pandava brothers. The suitors object the marriage of Draupadi and Arjuna, a fight ensues. Bhima and Arjuna defeat all the suitors and then takes Draupadi to their cottage. Kunti thinking Draupadi as alms commands her to be shared by the five brothers. Dhrishtadyumna gets to know the true identity of Pandavas.

13. Vaivahika Parva (Chapters: 195–201) Drupada is delighted at discovering that the Pandavas are alive. The Pandavas come to Drupada's palace. The story of Draupadi's previous lives and Indra punished by Shiva. The marriage of Draupadi with the Pandavas.

14. Viduragamana Parva (Chapters: 202–209) Vidura's attempt to reconcile the evil Kaurava brothers and the good Pandava brothers. Various speeches by Karna, Bhishma, Drona and Vidura. Pandavas return to Hastinapur with the blessings of Krishna. The construction of the city Indraprastha.

15. Rajya-labha Parva (Chapters: 210–214) Story of Sunda and Upasunda and of Narada.

16. Arjuna-vanavasa Parva (Chapters: 215–220) Arjuna violates dharma. He accepts voluntary exile. Arjuna marries Ulupi and Chitrangada, and rescues Apsaras. Story highlights his special powers and competence. Arjuna and Krishna become close friends. Arjuna goes to Dwarka, lives with Krishna.

17. Subhadra-harana Parva (Chapters: 221–222) Arjuna falls in love with and takes away Subhadra, Krishna's sister. The upset Vrishnis prepare war with Arjuna, but finally desist.

18. Harana-harana Parva a.k.a. Harana-harika Parva (Chapter: 223) Arjuna returns from exile, with Subhadra. They marry. Their son Abhimanyu is born. Story of the Upapandavas, the five sons of Draupadi.

19. Khandava-Daha Parva (Chapters: 224–236) The reign of Yudhishthira. Krishna and Arjuna go to the banks of Yamuna, where they meet Agni, disguised as a Brahmin, who demands to consume the Khandava forest, to cure his digestive ailment. Stories of Swetaki, and Agni. Agni gives Arjuna the Gandiva bow and the ape-bannered chariot, while Krishna receives the discus. Agni starts consuming the forest when Indra and other deities obstruct. The fight of Krishna and Arjuna with celestials, their combined abilities, and their victory. Story of Aswasena (Son of Takshaka), Mandapala and the his four bird sons. Maya rescued by Arjuna.[6]

English Translations

Adi Parva and other books of Mahabharata are written in Sanskrit. Several translations of the Adi Parva are available in English....

The translations are not consistent in parts and vary with each translator's interpretations...

The total number of original verses depend on which Sanskrit source is used, and these do not equal the total number of translated verses in each chapter, in both Ganguli and Dutt translations. Mahabharata, like many ancient Sanskrit texts, was transmitted across generations verbally, a practice that was a source of corruption of its text, deletion of verses as well as the addition of extraneous verses over time. Some of these suspect verses have been identified by change in style and integrity of meter in the verses. The structure, prose, meter and style of translations vary within chapters between the translating authors.

Debroy, in his 2011 overview of Mahabharata, notes that updated critical edition of Adi Parva, with spurious and corrupted text removed, has 19 sub-books, 225 adhyayas (chapters) and 7,205 shlokas (verses).

Controversies

Adi Parva, and Mahabharata in general, has been studied for evidence of caste-based social stratification in ancient India, as well as evidence for a host of theories about Vedic times in India. Such studies have become controversial.

First, the date and authenticity of the verses in Adi Parva, as well as the entire Mahabharata, has been questioned. Klaus Klostermaier, in his review of scholarly studies of Mahabharata, notes the widely held view that original Mahabharata was different from currently circulating versions. For centuries, the Mahabharata's 1, 00, 000 verses—four times the entire Bible and nine times the Iliad and the Odyssey combined—were transmitted verbally across generations, without being written down. This memorization and verbal method of transfer is believed to be a source of text corruption, addition and deletion of verses. Klostermaier notes that the original version of Mahabharata was called Jaya and had about 7000 shlokas or about 7% of current length. Adi Parva, and rest of Mahabharata, underwent at least two major changes - the first change tripled the size of Jaya epic and renamed it as Bharata, while the second change quadrupled the already expanded version. Significant changes to older editions have been traced to the first millennium CE. There are significant differences in Sanskrit manuscripts of the Mahabharata found in different parts of India and manuscripts of the Mahabharata found in other Indian languages such as Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu and others. Numerous spurious additions, interpolations and conflicting verses have been identified, many relating to history and social structure. Thus, it is unclear if the history or social structure of Vedic period or ancient India can be reliably traced from Adi Parva or Mahabharata.

Second, Adi Parva is part of an Epic fiction. Writers, including those such as Shakespeare or Homer, take liberty in developing their characters and plots, they typically represent extremes and they do not truthfully record extant history. [b]Adi Parva has verses with a story of a river fish swallowing a man's semen and giving birth to a human baby after 9 months and many other myths and fictional tales. Adi Parva, like the works of Homer and Shakespeare, is not a record of history.

Third, Adi Parva and other parvas of Mahabharata have been argued, suggests Klaus Klostermaier, as a treatise of symbolism, where each chapter has three different layers of meaning in its verses. The reader is painted a series of pictures through words, presented opposing views to various socio-ethical and moral questions, then left to interpret it on astikadi, manvadi and auparicara levels; in other words, as mundane interesting fiction, or as ethical treatise, or thirdly as transcendental work that draws out the war between the higher and the lower self within each reader. To deduce history of ancient India is one of many discursive choices for the interpreter.

-- Adi Parva, by Wikipedia

The Suparṇākhyāna, also known as the Suparṇādhyāya (meaning "Chapter of the Bird"), is a short epic poem or cycle of ballads in Sanskrit about the divine bird Garuda, believed to date from the late Vedic period. Considered to be among the "earliest traces of epic poetry in India," the text only survives "in very bad condition," and remains "little studied."

The subject of the poem is "the legend of Kadrū, the snake-mother, and Vinatā, the bird-mother, and enmity between Garuda and the snakes." It relates the birth of Garuda and his elder brother Aruṇa; Kadru and Vinata's wager about the color of the tail of the divine white horse Uchchaihshravas; Garuda's efforts to obtain freedom for himself and his mother; and his theft of the divine soma from Indra, whose thunderbolt is unable to stop Garuda, but merely causes him to drop a feather. It was the basis for the later, expanded version of the story, which appears in the Āstīka Parva, within the Ādi Parva of the Mahābhārata.

The Suparṇākhyāna's date of composition is uncertain; its unnamed author attempted to imitate the style of the Rigveda, but scholars agree that it is a significantly later composition, possibly from the time of the early Upanishads. On metrical grounds, it has been placed closest to the Katha Upanishad. A date of c. 500 BCE has been proposed, but is unproven, and is not agreed upon by all scholars.

-- Suparṇākhyāna, by Wikipedia

Historical references

See also: Bhagavad Gita § Date and text

The earliest known references to the Mahābhārata and its core Bhārata date to the Aṣṭādhyāyī (sutra 6.2.38) of Pāṇini (fl. 4th century BCE) and in the Aśvalāyana Gṛhyasūtra (3.4.4). This may mean the core 24,000 verses, known as the Bhārata, as well as an early version of the extended Mahābhārata, were composed by the 4th century BCE. A report by the Greek writer Dio Chrysostom (c. 40 – c. 120 CE) about Homer's poetry being sung even in India[33] seems to imply that the Iliad had been translated into Sanskrit. However, Indian scholars have, in general, take this as evidence for the existence of a Mahābhārata at this date, whose episodes Dio or his sources identify with the story of the Iliad.[34]

Several stories within the Mahābhārata took on separate identities of their own in Classical Sanskrit literature. For instance, Abhijñānaśākuntala by the renowned Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa (c. 400 CE), believed to have lived in the era of the Gupta dynasty, is based on a story that is the precursor to the Mahābhārata. Urubhaṅga, a Sanskrit play written by Bhāsa who is believed to have lived before Kālidāsa, is based on the slaying of Duryodhana by the splitting of his thighs by Bhīma.[35]

The copper-plate inscription of the Maharaja Sharvanatha (533–534 CE) from Khoh (Satna District, Madhya Pradesh) describes the Mahābhārata as a "collection of 100,000 verses" (śata-sahasri saṃhitā).[35]

The 18 parvas or books

The division into 18 parvas is as follows:

Parva / Title / Sub-parvas / Contents

1 / Adi Parva (The Book of the Beginning) / 1–19 / How the Mahābhārata came to be narrated by Sauti to the assembled rishis at Naimisharanya, after having been recited at the sarpasattra of Janamejaya by Vaisampayana at Takṣaśilā. The history and genealogy of the Bharata and Bhrigu races are recalled, as is the birth and early life of the Kuru princes (adi means first).

2 / Sabha Parva (The Book of the Assembly Hall) / 20–28 / Maya Danava erects the palace and court (sabha), at Indraprastha. Life at the court, Yudhishthira's Rajasuya Yajna, the game of dice, the disrobing of Pandava wife Draupadi and eventual exile of the Pandavas.

3 / Vana Parva also Aranyaka-Parva, Aranya-Parva (The Book of the Forest) / 29–44 / The twelve years of exile in the forest (aranya).

4 / Virata Parva (The Book of Virata) / 45–48 / The year spent incognito at the court of Virata.

5 / Udyoga Parva (The Book of the Effort) / 49–59 / Preparations for war and efforts to bring about peace between the Kaurava and the Pandava sides which eventually fail (udyoga means effort or work).

6 / Bhishma Parva (The Book of Bhishma) / 60–64 / The first part of the great battle, with Bhishma as commander for the Kaurava and his fall on the bed of arrows. (Includes the Bhagavad Gita in chapters 25–42.)[36][37]

7 / Drona Parva (The Book of Drona) / 65–72 / The battle continues, with Drona as commander. This is the major book of the war. Most of the great warriors on both sides are dead by the end of this book.

8 / Karna Parva (The Book of Karna) / 73 / The continuation of the battle with Karna as commander of the Kaurava forces.

9 / Shalya Parva (The Book of Shalya) / 74–77 / The last day of the battle, with Shalya as commander. Also told in detail, is the pilgrimage of Balarama to the fords of the river Saraswati and the mace fight between Bhima and Duryodhana which ends the war, since Bhima kills Duryodhana by smashing him on the thighs with a mace.

10 / Sauptika Parva (The Book of the Sleeping Warriors) / 78–80 /Ashvattama, Kripa and Kritavarma kill the remaining Pandava army in their sleep. Only 7 warriors remain on the Pandava side and 3 on the Kaurava side.

11 / Stri Parva (The Book of the Women) / 81–85 /Gandhari and the women (stri) of the Kauravas and Pandavas lament the dead and Gandhari cursing Krishna for the massive destruction and the extermination of the Kaurava.

12 / Shanti Parva (The Book of Peace) / 86–88 / The crowning of Yudhishthira as king of Hastinapura, and instructions from Bhishma for the newly anointed king on society, economics, and politics. This is the longest book of the Mahabharata. Kisari Mohan Ganguli considers this Parva as a later interpolation.'

13 / Anushasana Parva (The Book of the Instructions) / 89–90 / The final instructions (anushasana) from Bhishma.

14 / Ashvamedhika Parva (The Book of the Horse Sacrifice)[38] / 91–92 / The royal ceremony of the Ashvamedha (Horse sacrifice) conducted by Yudhishthira. The world conquest by Arjuna. Anita is told by Krishna to Arjuna.

15 / Ashramavasika Parva (The Book of the Hermitage) / 93–95 / The eventual deaths of Dhritarashtra, Gandhari, and Kunti in a forest fire when they are living in a hermitage in the Himalayas. Vidura predeceases them and Sanjaya on Dhritarashtra's bidding goes to live in the higher Himalayas.

16 / Mausala Parva (The Book of the Clubs) / 96 / The materialization of Gandhari's curse, i.e., the infighting between the Yadavas with maces (mausala) and the eventual destruction of the Yadavas.

17 / Mahaprasthanika Parva (The Book of the Great Journey) / 97 / The great journey of Yudhishthira, his brothers, and his wife Draupadi across the whole country and finally their ascent of the great Himalayas where each Pandava falls except for Yudhishthira.

18 / Svargarohana Parva (The Book of the Ascent to Heaven) / 98 / Yudhishthira's final test and the return of the Pandavas to the spiritual world (svarga).

khila / Harivamsa Parva (The Book of the Genealogy of Hari) / 99–100 / This is an addendum to the 18 books, and covers those parts of the life of Krishna which is not covered in the 18 parvas of the Mahabharata.

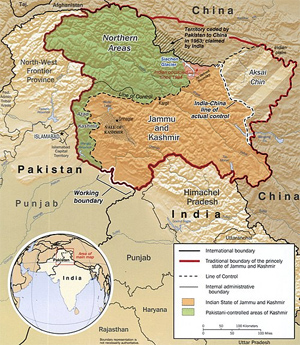

Historical context

The historicity of the Kurukshetra War is unclear. Many historians estimate the date of the Kurukshetra war to Iron Age India of the 10th century BCE.[39] The setting of the epic has a historical precedent in Iron Age (Vedic) India, where the Kuru kingdom was the center of political power during roughly 1200 to 800 BCE.[40] A dynastic conflict of the period could have been the inspiration for the Jaya, the foundation on which the Mahābhārata corpus was built, with a climactic battle, eventually coming to be viewed as an epochal event.

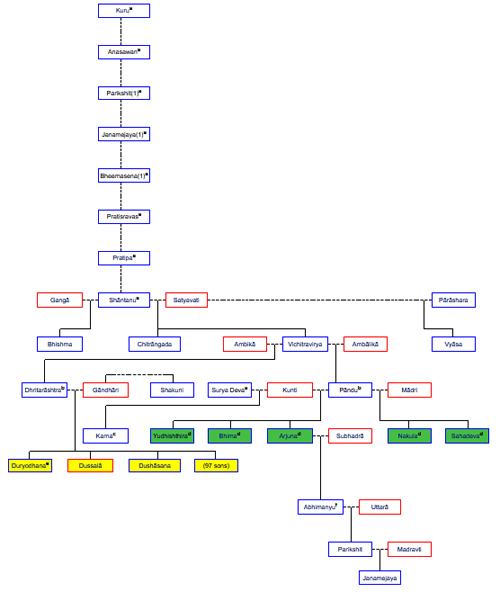

Puranic literature presents genealogical lists associated with the Mahābhārata narrative. The evidence of the Puranas is of two kinds. Of the first kind, there is the direct statement that there were 1015 (or 1050) years between the birth of Parikshit (Arjuna's grandson) and the accession of Mahapadma Nanda (400-329 BCE), which would yield an estimate of about 1400 BCE for the Bharata battle.[41] However, this would imply improbably long reigns on average for the kings listed in the genealogies.[42] Of the second kind is analyses of parallel genealogies in the Puranas between the times of Adhisimakrishna (Parikshit's great-grandson) and Mahapadma Nanda. Pargiter accordingly estimated 26 generations by averaging 10 different dynastic lists and, assuming 18 years for the average duration of a reign, arrived at an estimate of 850 BCE for Adhisimakrishna, and thus approximately 950 BCE for the Bharata battle.[43]

Map of some Painted Grey Ware (PGW) sites.

B. B. Lal used the same approach with a more conservative assumption of the average reign to estimate a date of 836 BCE, and correlated this with archaeological evidence from Painted Grey Ware (PGW) sites, the association being strong between PGW artifacts and places mentioned in the epic.[44] John Keay confirms this and also gives 950 BCE for the Bharata battle.[45]

Attempts to date the events using methods of archaeoastronomy have produced, depending on which passages are chosen and how they are interpreted, estimates ranging from the late 4th to the mid-2nd millennium BCE.[46] The late 4th-millennium date has a precedent in the calculation of the Kali Yuga epoch, based on planetary conjunctions, by Aryabhata (6th century). Aryabhata's date of 18 February 3102 BCE for Mahābhārata war has become widespread in Indian tradition. Some sources mark this as the disappearance of Krishna from the earth.[47] The Aihole inscription of Pulikeshi II, dated to Saka 556 = 634 CE, claims that 3735 years have elapsed since the Bharata battle, putting the date of Mahābhārata war at 3137 BCE.[48][49] Another traditional school of astronomers and historians, represented by Vriddha-Garga, Varahamihira (author of the Brhatsamhita) and Kalhana (author of the Rajatarangini), place the Bharata war 653 years after the Kali Yuga epoch, corresponding to 2449 BCE.[50]

Characters

Main article: List of characters in Mahabharata

Synopsis

Ganesha writes the Mahabharata upon Vyasa's dictation.

The core story of the work is that of a dynastic struggle for the throne of Hastinapura, the kingdom ruled by the Kuru clan. The two collateral branches of the family that participate in the struggle are the Kaurava and the Pandava. Although the Kaurava is the senior branch of the family, Duryodhana, the eldest Kaurava, is younger than Yudhishthira, the eldest Pandava. Both Duryodhana and Yudhishthira claim to be first in line to inherit the throne.

The struggle culminates in the great battle of Kurukshetra, in which the Pandavas are ultimately victorious. The battle produces complex conflicts of kinship and friendship, instances of family loyalty and duty taking precedence over what is right, as well as the converse.

The Mahābhārata itself ends with the death of Krishna, and the subsequent end of his dynasty and ascent of the Pandava brothers to heaven. It also marks the beginning of the Hindu age of Kali Yuga, the fourth and final age of humankind, in which great values and noble ideas have crumbled, and people are heading towards the complete dissolution of right action, morality, and virtue.

The older generations

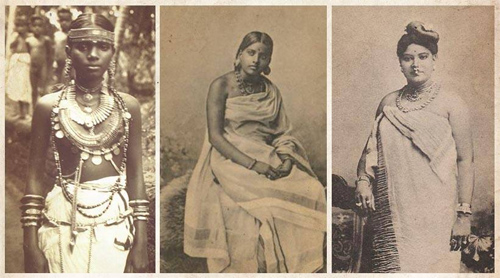

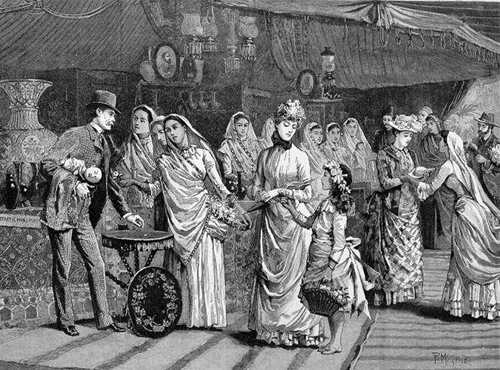

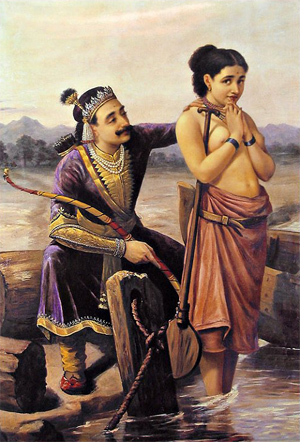

Shantanu woos Satyavati, the fisherwoman. Painting by Raja Ravi Varma.

King Janamejaya's ancestor Shantanu, the king of Hastinapura, has a short-lived marriage with the goddess Ganga and has a son, Devavrata (later to be called Bhishma, a great warrior), who becomes the heir apparent. Many years later, when King Shantanu goes hunting, he sees Satyavati, the daughter of the chief of fisherman, and asks her father for her hand. Her father refuses to consent to the marriage unless Shantanu promises to make any future son of Satyavati the king upon his death. To resolve his father's dilemma, Devavrata agrees to relinquish his right to the throne. As the fisherman is not sure about the prince's children honoring the promise, Devavrata also takes a vow of lifelong celibacy to guarantee his father's promise.

Shantanu has two sons by Satyavati, Chitrāngada and Vichitravirya. Upon Shantanu's death, Chitrangada becomes king. He lives a very short uneventful life and dies. Vichitravirya, the younger son, rules Hastinapura. Meanwhile, the King of Kāśī arranges a swayamvara for his three daughters, neglecting to invite the royal family of Hastinapur. To arrange the marriage of young Vichitravirya, Bhishma attends the swayamvara of the three princesses Amba, Ambika, and Ambalika, uninvited, and proceeds to abduct them. Ambika and Ambalika consent to be married to Vichitravirya.

The oldest princess Amba, however, informs Bhishma that she wishes to marry the king of Shalva whom Bhishma defeated at their swayamvara. Bhishma lets her leave to marry the king of Shalva, but Shalva refuses to marry her, still smarting at his humiliation at the hands of Bhishma. Amba then returns to marry Bhishma but he refuses due to his vow of celibacy. Amba becomes enraged and becomes Bhishma's bitter enemy, holding him responsible for her plight. Later she is reborn to King Drupada as Shikhandi (or Shikhandini) and causes Bhishma's fall, with the help of Arjuna, in the battle of Kurukshetra.

The Pandava and Kaurava princes

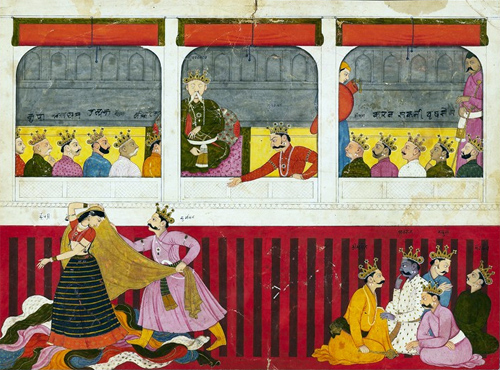

Draupadi with her five husbands – the Pandavas. The central figure is Yudhishthira; the two on the bottom are Bhima and Arjuna. Nakula and Sahadeva, the twins, are standing. Painting by Raja Ravi Varma, c. 1900.

When Vichitravirya dies young without any heirs, Satyavati asks her first son Vyasa to father children with the widows. The eldest, Ambika, shuts her eyes when she sees him, and so her son Dhritarashtra is born blind. Ambalika turns pale and bloodless upon seeing him, and thus her son Pandu is born pale and unhealthy (the term Pandu may also mean 'jaundiced'[51]). Due to the physical challenges of the first two children, Satyavati asks Vyasa to try once again. However, Ambika and Ambalika send their maid instead, to Vyasa's room. Vyasa fathers a third son, Vidura, by the maid. He is born healthy and grows up to be one of the wisest characters in the Mahabharata. He serves as Prime Minister (Mahamantri or Mahatma) to King Pandu and King Dhritarashtra.

When the princes grow up, Dhritarashtra is about to be crowned king by Bhishma when Vidura intervenes and uses his knowledge of politics to assert that a blind person cannot be king. This is because a blind man cannot control and protect his subjects. The throne is then given to Pandu because of Dhritarashtra's blindness. Pandu marries twice, to Kunti and Madri. Dhritarashtra marries Gandhari, a princess from Gandhara, who blindfolds herself for the rest of her life so that she may feel the pain that her husband feels. Her brother Shakuni is enraged by this and vows to take revenge on the Kuru family. One day, when Pandu is relaxing in the forest, he hears the sound of a wild animal. He shoots an arrow in the direction of the sound. However, the arrow hits the sage Kindama, who was engaged in a sexual act in the guise of a deer. He curses Pandu that if he engages in a sexual act, he will die. Pandu then retires to the forest along with his two wives, and his brother Dhritarashtra rules thereafter, despite his blindness.

Pandu's older queen Kunti, however, had been given a boon by Sage Durvasa that she could invoke any god using a special mantra. Kunti uses this boon to ask Dharma the god of justice, Vayu the god of the wind, and Indra the lord of the heavens for sons. She gives birth to three sons, Yudhishthira, Bhima, and Arjuna, through these gods. Kunti shares her mantra with the younger queen Madri, who bears the twins Nakula and Sahadeva through the Ashwini twins. However, Pandu and Madri indulge in lovemaking, and Pandu dies. Madri commits suicide out of remorse. Kunti raises the five brothers, who are from then on usually referred to as the Pandava brothers.

Dhritarashtra has a hundred sons through Gandhari, all born after the birth of Yudhishthira. These are the Kaurava brothers, the eldest being Duryodhana, and the second Dushasana. Other Kaurava brothers were Vikarna and Sukarna. The rivalry and enmity between them and the Pandava brothers, from their youth and into manhood, leads to the Kurukshetra war.

Lakshagraha (the house of lac)

After the deaths of their mother (Madri) and father (Pandu), the Pandavas and their mother Kunti return to the palace of Hastinapur. Yudhishthira is made Crown Prince by Dhritarashtra, under considerable pressure from his courtiers. Dhritarashtra wanted his son Duryodhana to become king and lets his ambition get in the way of preserving justice.

Shakuni, Duryodhana, and Dushasana plot to get rid of the Pandavas. Shakuni calls the architect Purochana to build a palace out of flammable materials like lac and ghee. He then arranges for the Pandavas and the Queen Mother Kunti to stay there, intending to set it alight. However, the Pandavas are warned by their wise uncle, Vidura, who sends them a miner to dig a tunnel. They can escape to safety and go into hiding. During this time Bhima marries a demoness Hidimbi and has a son Ghatotkacha. Back in Hastinapur, the Pandavas and Kunti are presumed dead.[52]

Marriage to Draupadi

Arjuna piercing the eye of the fish as depicted in Chennakesava Temple built by Hoysala Empire

Whilst they were in hiding the Pandavas learn of a swayamvara which is taking place for the hand of the Pāñcāla princess Draupadī. The Pandavas disguised as Brahmins come to witness the event. Meanwhile, Krishna who has already befriended Draupadi, tells her to look out for Arjuna (though now believed to be dead). The task was to string a mighty steel bow and shoot a target on the ceiling, which was the eye of a moving artificial fish while looking at its reflection in oil below. In popular versions, after all the princes fail, many being unable to lift the bow, Karna proceeds to the attempt but is interrupted by Draupadi who refuses to marry a suta (this has been excised from the Critical Edition of Mahabharata[53][54] as later interpolation[55]). After this the swayamvara is opened to the Brahmins leading Arjuna to win the contest and marry Draupadi. The Pandavas return home and inform their meditating mother that Arjuna has won a competition and to look at what they have brought back. Without looking, Kunti asks them to share whatever Arjuna has won amongst themselves, thinking it to be alms. Thus, Draupadi ends up being the wife of all five brothers.

Indraprastha

After the wedding, the Pandava brothers are invited back to Hastinapura. The Kuru family elders and relatives negotiate and broker a split of the kingdom, with the Pandavas obtaining and demanding only a wild forest inhabited by Takshaka, the king of snakes, and his family. Through hard work, the Pandavas can build a new glorious capital for the territory at Indraprastha.

Shortly after this, Arjuna elopes with and then marries Krishna's sister, Subhadra. Yudhishthira wishes to establish his position as king; he seeks Krishna's advice. Krishna advises him, and after due preparation and the elimination of some opposition, Yudhishthira carries out the rājasūya yagna ceremony; he is thus recognized as pre-eminent among kings.

The Pandavas have a new palace built for them, by Maya the Danava.[56] They invite their Kaurava cousins to Indraprastha. Duryodhana walks round the palace, and mistakes a glossy floor for water, and will not step in. After being told of his error, he then sees a pond and assumes it is not water and falls in. Bhima, Arjun, the twins and the servants laugh at him.[57] In popular adaptations, this insult is wrongly attributed to Draupadi, even though in the Sanskrit epic, it was the Pandavas (except Yudhishthira) who had insulted Duryodhana. Enraged by the insult, and jealous at seeing the wealth of the Pandavas, Duryodhana decides to host a dice-game at Shakuni's suggestion.

The dice game

Draupadi humiliated

Shakuni, Duryodhana's uncle, now arranges a dice game, playing against Yudhishthira with loaded dice. In the dice game, Yudhishthira loses all his wealth, then his kingdom. Yudhishthira then gambles his brothers, himself, and finally his wife into servitude. The jubilant Kauravas insult the Pandavas in their helpless state and even try to disrobe Draupadi in front of the entire court, but Draupadi's disrobe is prevented by Krishna, who miraculously make her dress endless, therefore it couldn't be removed.

Dhritarashtra, Bhishma, and the other elders are aghast at the situation, but Duryodhana is adamant that there is no place for two crown princes in Hastinapura. Against his wishes Dhritarashtra orders for another dice game. The Pandavas are required to go into exile for 12 years, and in the 13th year, they must remain hidden. If they are discovered by the Kauravas in the 13th year of their exile, then they will be forced into exile for another 12 years.

Exile and return

The Pandavas spend thirteen years in exile; many adventures occur during this time. The Pandavas acquire many divine weapons, given by gods, during this period. They also prepare alliances for a possible future conflict. They spend their final year in disguise in the court of the king Virata, and they are discovered just after the end of the year.

At the end of their exile, they try to negotiate a return to Indraprastha with Krishna as their emissary. However, this negotiation fails, because Duryodhana objected that they were discovered in the 13th year of their exile and the return of their kingdom was not agreed upon. Then the Pandavas fought the Kauravas, claiming their rights over Indraprastha.

The battle at Kurukshetra

Main article: Kurukshetra War

A scene from the Mahābhārata war, Angkor Wat: A black stone relief depicting several men wearing a crown and a dhoti, fighting with spears, swords, and bows. A chariot with half the horse out of the frame is seen in the middle.

The two sides summon vast armies to their help and line up at Kurukshetra for a war. The kingdoms of Panchala, Dwaraka, Kasi, Kekaya, Magadha, Matsya, Chedi, Pandyas, Telinga, and the Yadus of Mathura and some other clans like the Parama Kambojas were allied with the Pandavas. The allies of the Kauravas included the kings of Pragjyotisha, Anga, Kekaya, Sindhudesa (including Sindhus, Sauviras and Sivis), Mahishmati, Avanti in Madhyadesa, Madra, Gandhara, Bahlika people, Kambojas and many others. Before war being declared, Balarama had expressed his unhappiness at the developing conflict and leaves to go on pilgrimage; thus he does not take part in the battle itself. Krishna takes part in a non-combatant role, as charioteer for Arjuna.

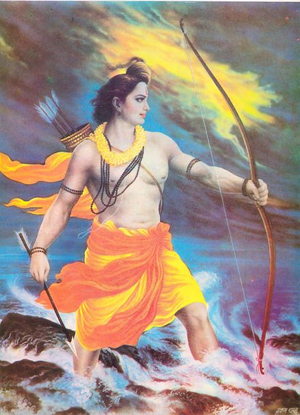

Before the battle, Arjuna, noticing that the opposing army includes his cousins and relatives, including his grandfather Bhishma and his teacher Drona, has grave doubts about the fight. He falls into despair and refuses to fight. At this time, Krishna reminds him of his duty as a Kshatriya to fight for a righteous cause in the famous Bhagavad Gita section of the epic.

Though initially sticking to chivalrous notions of warfare, both sides soon adopt dishonorable tactics. At the end of the 18-day battle, only the Pandavas, Satyaki, Kripa, Ashwatthama, Kritavarma, Yuyutsu and Krishna survive. Yudhisthir becomes King of Hastinapur and Gandhari curses Krishna that the downfall of his clan is imminent.

The end of the Pandavas

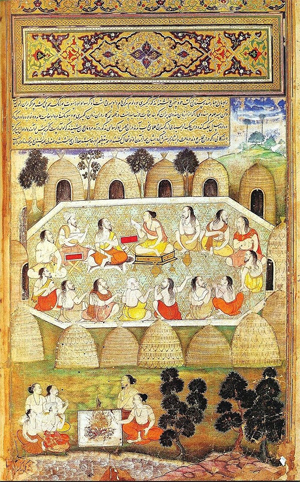

Gandhari, blindfolded, supporting Dhrtarashtra and following Kunti when Dhritarashtra became old and infirm and retired to the forest. A miniature painting from a 16th-century manuscript of part of the Razmnama, a Persian translation of the Mahabharata

After "seeing" the carnage, Gandhari, who had lost all her sons, curses Krishna to be a witness to a similar annihilation of his family, for though divine and capable of stopping the war, he had not done so. Krishna accepts the curse, which bears fruit 36 years later.

The Pandavas, who had ruled their kingdom meanwhile, decide to renounce everything. Clad in skins and rags they retire to the Himalaya and climb towards heaven in their bodily form. A stray dog travels with them. One by one the brothers and Draupadi fall on their way. As each one stumbles, Yudhishthira gives the rest the reason for their fall (Draupadi was partial to Arjuna, Nakula and Sahadeva were vain and proud of their looks, and Bhima and Arjuna were proud of their strength and archery skills, respectively). Only the virtuous Yudhishthira, who had tried everything to prevent the carnage, and the dog remain. The dog reveals himself to be the god Yama (also known as Yama Dharmaraja) and then takes him to the underworld where he sees his siblings and wife. After explaining the nature of the test, Yama takes Yudhishthira back to heaven and explains that it was necessary to expose him to the underworld because (Rajyante narakam dhruvam) any ruler has to visit the underworld at least once. Yama then assures him that his siblings and wife would join him in heaven after they had been exposed to the underworld for measures of time according to their vices.

Arjuna's grandson Parikshit rules after them and dies bitten by a snake. His furious son, Janamejaya, decides to perform a snake sacrifice (sarpasattra) to destroy the snakes. It is at this sacrifice that the tale of his ancestors is narrated to him.