CHAP. XX. Of what concerns Women. Excerpt from A Code of Gentoo Laws, Or, Ordinations of the Pundits

From a Persian Translation, Made From the Original, Written in the Shanscrit Language

by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed

1776

CHAP. XX. Of what concerns Women.

A Man, both Day and Night, must keep his Wife so much in Subjection, that she by no Means be Mistress of her own Actions: If the Wife have her own Free-Will, notwithstanding she be sprung from a superior Cast, she will yet behave amiss.

So long as a Woman remains unmarried, her Father shall take care of her; and so long as a Wife remains young, her Husband shall take care of her; and in her old Age, her Son shall take care of her; and if, before a Woman's Marriage, her Father should die, the Brother, or Brother's Son, or such other near Relations of the Father shall take care of her; if, after Marriage, her Husband should die, and the Wife has not brought forth a Son, the Brothers, and Brothers Sons, and such other near Relations of her Husband shall take care of her: If there are no Brothers, Brothers Sons, or such other near Relations of her Husband, the Brothers, or Sons of the Brothers of her Father shall take care of her: If there are none of those, the Magistrate shall take care of her; and in every Stage of Life, if the Persons who have been allotted to take care of a Woman do not take care of her, each in his respective Stage accordingly, the Magistrate shall fine them.

If a Husband be abject: and weak, he shall nevertheless endeavour to guard his Wife with Caution, that she may not be unchaste, and learn bad Habits.

If a Man, by Confinement and Threats, cannot guard his Wife, he shall give her a large Sum of Money, and make her Mistress of her Income and Expences, and appoint her to dress Victuals for the Dewtah (i. e.) the Deity.

A Woman is never satisfied with the Copulation of Man, no more than Fire is satisfied with burning Fuel, or the main Ocean with receiving the Rivers, or the Empire of Death with the dying of Men and Animals; in this Case therefore, a Woman is not to be relied on.

Women have Six Qualities; the First, an inordinate Desire for Jewels and fine Furniture, handsome Cloaths, and nice Victuals; the Second, immoderate Lust; the Third, violent Anger; the Fourth, deep Resentment (i. e.) no Person knows the Sentiments concealed in their Heart; the Fifth, another Person's Good appears Evil in their Eyes; the Sixth, they commit bad Actions.

If a Woman is pregnant, they must give her the Sadheh (the Sadheh is, to give a pregnant Woman, in the Ninth Month, Rice, Milk, and Sweetmeats, and other Eatables of the same Kind for her to eat, and to dress her in handsome Cloaths.

If a Husband is going a Journey, he must give his Wife enough to furnish her with Victuals and Cloaths, until the promised Period of his Return; if he goes without leaving such Provision, and his Wife is reduced to great Necessity for want of Victuals and Cloaths, then, if the Wife be naturally well principled, she yet becomes unchaste, for want of Victuals and Cloaths.

In every Family where there is a good Understanding between the Husband and Wife, and where the Wife is not unchaste, and the Husband also commits no bad Practices, it is an excellent Example.

The Creator formed Woman for this Purpose, viz. That Man might copulate with her, and that Children might be born from thence.

A Woman, who always acts according to her Husband's Pleasure, and speaks no ill of any Person, and who can herself do all such Things as are proper for a Woman, and who is of good Principles, and who produces a Son, and who rises from Sleep before her Husband, such a Woman is found only by much and many religious Works, and by a peculiarly happy Destiny, such a Woman, if any Man forsakes of his own accord, the Magistrate shall inflict upon that Man the Punishment of a Thief.

A Woman, who always abuses her Husband, shall be treated with good Advice, for the Space of One Year; if she does not amend with One Year's Advice, and does not leave off abusing her Husband, he shall no longer hold any Communication with her, nor keep her any longer near him, but shall provide her with Food and Cloaths.

A Woman, who dissipates or spoils her own Property, or who procures Abortion, or who has an Intention to murder her Husband, and is always quarrelling with every Body, and who eats before her Husband eats, such Woman shall be turned out of the House.

A Husband, at his own Pleasure, shall cease to copulate with his Wife who is barren, or who always brings forth Daughters.

If a Woman, after her monthly Courses, while her Husband continues in the House, conceiving her Husband to be a weak, low, and contemptible Object, goes no more to him, the Husband, informing People of this, shall turn her out of his House.

If a Woman, following her own Inclination, goes whithersoever she chooses, and does not regard the Words of her Master, such a Woman also shall be turned away.

A Woman, who is of a good Disposition, and who puts on her Jewels and Cloaths with Decorum, and is of good Principles, whenever the Husband is cheerful, the Wife also is cheerful, and if the Husband is sorrowful, the Wife also is sorrowful, and whenever the Husband undertakes a Journey, the Wife puts on a careless Dress, and lays aside her Jewels and other Ornaments, and abuses no Person, and will not expend a single Dam without her Husband's Consent, and has a Son, and takes proper Care of the Household Goods, and, at the Times of Worship, performs her Worship to the Deity in a proper Manner, and goes not out of the House, and is not unchaste, and makes no Quarrels or Disturbances, and has no greedy Passions, and is always employed in some good Work, and pays a proper Respect to all Persons, such is a good Woman.

A Woman shall never go out of the House without the Consent of her Husband, and shall always have some Cloaths upon her Bosom, and at Festival Times shall put on her choicest Dress and her Jewels, and shall never hold Discourse with a strange Man; but may converse with a Sinassee, a Hermit, or an old Man; and shall always dress in Cloaths that reach from below the Leg to above the Navel; and shall not suffer her Breasts to appear out of her Cloaths; and shall not laugh, without drawing her Veil before her Face; and shall act according to the Orders of her Husband; and shall pay a proper Respect to the Deity, her Husband's Father, the Spiritual Guide, and the Guests; and shall not eat until she has served them with Victuals (if it is Physick, she may take it before they eat) a Woman also shall never go to a Stranger's House, and shall not stand at the Door, and must never look out of a window.

Six Things are disgraceful to a Woman: 1st. To drink Wine and eat Conserves, or any such inebriating Things. 2d. To keep company with a Man of bad Principles. 3d. To remain separate from her Husband. 4th. To go to a Stranger's House without good Cause. 5th. To sleep in the Day- Time. 6th. To remain in a Stranger's House.

When a Woman, whose Husband is Absent on a Journey, has expended all the Money that he gave her, to support her in Victuals and Cloaths during his Absence, or if her Husband went on a Journey without leaving any Thing with her to support her Expences, she shall support herself by Painting, by Spinning, or some other such Employment.

If a Man goes on a Journey, his Wife shall not divert herself by Play, nor shall see any publick Show, nor shall laugh, nor shall dress herself in Jewels and fine Cloaths, nor shall see Dancing, nor hear Musick, nor shall sit in the Window, nor shall ride out, nor shall behold any Thing choice and rare; but shall fasten well the House-Door, and remain private; and shall not eat any dainty Victuals, and shall not blacken her Eyes with Eye-Powder, and shall not view her Face in a Mirror; she shall never exercise herself in any such agreeable Employment, during the Absence of her Husband.

It is proper for a Woman, after her Husband's Death, to burn herself in the Fire with his Corpse; every Woman, who thus burns herself, shall remain in Paradise with her Husband Three Crore and Fifty Lacks of Years, by Destiny; if she cannot burn, she must, in that Case, preserve an inviolable Chastity; if she remains always chaste, she goes to Paradise; and if she does not preserve her Chastity, she goes to Hell.

Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Ramchandra Pant Amatya

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/24/21

Ramchandra Pant Amatya Bavdekar

Ramchandra Pant Amatya Painting made from earlier statue. Artist Swapnil Patil.

Flag of the Maratha Empire.svgAmatya of the Maratha Empire

In office: 1674–1689

Monarch Chhatrapati Shivaji I; Sambhaji

Preceded by: position established

Succeeded by: Bahiroji Pingale

Regent of the Maratha Empire

In office: 1689–1708

Monarch: Sambhaji; Rajaram; Shivaji II; Sambhaji II

Preceded by: Moreshvar Pingale

Succeeded by: Bahiroji Pingale

Personal details

Born: 1650, Kolwan (Pune District, Maharashtra)

Died: 1716, Panhala (Kolhapur District, Maharashtra)

Spouse(s): Janakibai

Ramchandra Neelkanth Bawadekar (1650–1716), also known as Ramchandra Pant Amatya, served on the Council of 8 (Ashta Pradhan) as the Finance Minister (Amatya) to Emperor (Chhatrapati) Shivaji dating from 1674 to 1680.[1] He then served as the Imperial Regent to four later emperors, namely Sambhaji, Rajaram, Shivaji II and Sambhaji II. He authored the Adnyapatra, a famous code of civil and military administration, and is renowned as one of the greatest civil administrators, diplomats and military strategists of the Maratha Empire.

Early life

Ramchandra Pant was born in a Deshastha Brahmin family in approximately 1650. He was the youngest son of Neelkanth Sondeo Bahutkar (more popularly known as Nilo Sondeo), who had risen from a local revenue collection post (Kulkarni) to the post of Minister in the court of Shivaji.

His family came from the village of Kolwan; near Kalyan Bhiwandi. Ramchandra Pant's grandfather Sonopant and uncle Abaji Sondeo were in the close circle of Shivaji. The Bahutkar family was closely associated with Samarth Ramdas, the spiritual guru of Shivaji. Samarth Ramdas is believed to be the one who named the newly born child as Ramchandra.

Early career

Before 1672, Ramchandra Pant was engaged in various clerical jobs in Shivaji's administration. In 1672, he and his elder brother Narayan were both promoted to the post of Revenue Minister (Mujumdar) by Shivaji. In 1674, at the coronation ceremony, the post of Mujumdar was renamed as Amatya and the title was solely bestowed upon Ramchandra Pant. He worked in this capacity until 1678. On his death bed, Shivaji named him as one among six pillars of the Maratha Empire that would save the kingdom in difficult times.

After Shivaji's death in 1680, Sambhaji became ruler of the Maratha Empire, and Ramchandra Pant continued with his administration in various posts. Among other duties, Ramchandra Pant was sent to Prince Akbar, Aurangzeb's rebel son, for negotiations and, in 1685, Sambhaji also deployed him as an envoy to Vijapur for certain sensitive talks.

Amatya of 5 Chhatrapaties

Ramchandra Pant Amatya was the only person (Amatya) who dedicatedly served The Maratha Swarajya under 5 Chhatrapati's in a row. When the Marathi empire was in trouble he used his wisdom, dedication to the throne and even force as needed to keep the empire and its Swarajya safe.

During the coronation of Shivaji, Ramchandra Pant Amatya was the youngest Pradhan of all the Asthapradhan's existing at that time. Thereafter, during the reign of Sambhaji, Rajaram, Maharani Tarabai and (Kolhapur's first ruler) Sambhaji Raje, Pant Amatya always held a prominent positions. As Riyasatkar(s) rightly said that ‘ever since the time of Shivaji Maharaj, Ramchandra Pant Amatya was the only person in the history of the Marathas who seems to have dedicatedly served the throne.’ Ramchandra Pant Amatya has laid down all the experiences encountered by him, while serving the throne in his book Rajniti (Adnyapatra). The said book is a testament to his dedication and service to the throne of Chatrapati's and Hindavi Swarajya.

The forefathers of Ramchandra Pant Amatya had close relations with the Bhosle Gharana even before the establishment of Swarajya. Before the coronation of Shivaji, Ramchandra Pant Amatya's father used to participate in various initiatives undertaken by Shivaji. Ramchandra Pant Amatya subsequently carried forward this (his father's) tradition with even more impact. Ramchandra Pant Amatya took the lead when it came to the protection of the Swarajya. Being impressed by his efforts, Shivaji included Ramchandra Pant as Amatya in his First Ashta Pradhan mandal i.e. Council of Ministers. This, in itself portrays the qualities that Ramchandra Pant Amatya possessed. During the coronation ceremony of Shivaji, Pant was included as Amatya. He must’ve been 22–23 years old then. Before the coronation, a Pradhan Mandal was appointed by Maharaj in the year 1662 which included Ramchandra Pant's father Neelkanth Sondev as Maharaj's Amatya. This legacy was carried forward, as after the death of Neelkanth Sondev his son Ramchandra Pant was appointed as Maharaj's Amatya.

According to the information provided by the Bakharkar(s), Ramchandra Pant Amatya was one of the very few people present when Shivaji was on his death bed at Raigad. Shivaji had named a few people who had the ability protect the Swarajya after his demise. Ramchandra Pant Amatya was one of them. During the Reign of Sambhaji, Ramchandra Pant Amatya was given an important position. (Period of 1680 to 1685)

Fight for Freedom

After the unfortunate demise of Sambhaji, the Maratha Empire was in great trouble. Aurangzeb had taken a vow to defeat the Maratha empire at any cost, and with that motive, he attacked many forts of the Marathas with a huge army. Sadness prevailed all over the Maratha Empire. In this situation, Ramchandra Pant Amatya stood up and acted with a lot of patience. This was the era of the freedom struggle of the Maratha empire. Ramchandra Pant Amatya did every thing he could to keep the royal family and the Maratha empire safe and endure the struggle of the troubled times. Ramchandra Pant Amatya, Santaji Ghorpade, Dhanaji Jadhav, Parshurampant Pant-Pratinidhi were the major contributors to the struggle for freedom.[citation needed]

Rajaram Maharaj's stay in Gingi ended in 1697. He returned to Maharashtra. However, Rajaram Maharaj died in 1700 when he was at Fort Sinhagad. The Maratha empire was in trouble again. Ramchandra Pant Amatya did everything he could to save the Maratha Empire from the trouble and he succeeded. This was no mean achievement. Ramchandra Pant had paid a visit to Rajaram Maharaj when he was on his death bed at Sinhagad fort. Pant had sensed the inevitable. He wrote letters to many Sardars and informed them of the dire situation and brought to their notice, the need to protect the Empire.

After the death of Rajaram Maharaj, Aurangzeb started attacking with even more force. He thought that now, he could easily defeat the Maratha empire as there was no King. He planned to take over the entire empire. But he was wrong. Ramchandra Pant, Dhanaji Jadhav, Parshuram Pant Pratinidhi along with thousands of soldiers loyal and dedicated to the throne resolved to defend their Empire. They fought with Aurangzeb for seven years continuously, that is from 1700 to 1707. Eventually, Aurangzeb admitted defeat and subsequently died in Ahmednagar. This struggle for 7 continuous years was a period with innumerable difficulties and troubles for the Marathas. The leadership of Maharani Tarabai and the wisdom of Ramchandra Pant had played a vital role in the protection of the Swarajya in these 7 years. Tarabai wanted her son Shivaji II on the Maratha throne but Ramchandra Pant wanted to wait for Prince Shahu to return. But he did not pursue it beyond a point. He decided to be loyal to the Kolhapur throne. Tararani knew about Ramchandra Pant's capabilities and qualities. In every time of peril, he stood behind the Maratha throne like a mountain. Tarabai has in a letter to his son Bhagwantrao acknowledged his greatness. She says, "Ramchandra Pant served the Maratha kingdom with great loyalty. He restored an almost finished Swarajya and made a great name for himself ".[citation needed]

It is said that Ramchandra Pant Amatya was behind the bloodless coup that led to Rajasbai's son Sambhaji being crowned as The Chatrapati in 1713-1714. He felt it necessary as the Kolhapur Kingdom was heading towards a different path. There seems to be no ulterior motive behind this coup. He crowned Sambhaji as the Chatrapati and soon went in the background. As Sambhaji was only 16–17 years old he would naturally look up to Ramchandra Pant Amatya for guidance. Shortly after Ramchandra Pant Amatya died. There is some confusion about the date of his death but most historians assume it to be somewhere in February 1716.[citation needed]

A Warrior and A Statesman

Ramchandra Pant Amatya was also a warrior as he was a statesman. He is known to lead many wars. Moghul historians mention that when Aurangzeb's grandson had invaded Panhala in 1693 Ramchandra Pant along with Pratinidhi launched a heavy attack on the Mughal forces. A Farsi historian notes that Ramchandra Pant was the head of Konkan army in 1699 and attacked them with all his might. His guns were blazing with all their might and a mighty war ensued.[citation needed]

A Portuguese Killedar has mentioned that on 22 February 1701 Ramchandra Pant along with 20,000 Maratha's attacked Dandya's Siddi Yakubkhan.

Adnyapatra

Coat of Arms of Pant Amatya Gaganbavada

Ramchandra Pant Amatya is the writer of the First book on Politics in Maratha history "AdnyaPatra". This main topics refer to

1. The King and his duties ways of governance,

2. How revenue is important for the State

3. Importance of the Army and Importance of scholars and experts in all fields

4. Education of the Princes.

5. Importance of a Pradhan i.e. Prime Minister and his duties

6. Policies regarding foreigners i.e. British, French etc.

7. Policy regarding your judicatories

8. Importance of forts.

9. he who has the Navy rules the seas,

10. Policy regarding natural resources etc.

It is said that it outlines the theories and way of ruling of Shivaji. The book is said to be of such high stature that it can be compared to Kautilya's Arthashastra.

It is said that the book still holds relevance in today's time and can be a guide for a person in the administration of a state, such is the richness of his thoughts more than 300 years back.

Contribution to Maratha War of Independence

In 1689, at the time of Sambhaji's assassination by Aurangzeb, Ramchandra Pant was deployed at Fort Vishalgad. In consultation with Sambhaji's queen, Yesubai, who was located at Fort Raigad along with Rajaram and her son Shahu, he decided to send Rajaram to Fort Gingee (in current-day Tamil Nadu) to divide the battlefield. Subsequently, Rajaram was brought to Panhala fort and was secretly sent to Gingee. Before leaving for Gingee, Rajaram conferred on Ramchandra Pant the title of Imperial Regent (Hukumat Panah).

Thereafter, with the aid of generals Santaji Ghorpade, Dhanaji Jadhav, Parshuram Pant Pratinidhi, and Shankaraji Narayan Gandekar, Ramchandra Pant launched a great retaliatory war against the Mughal Empire.

Wartime strategies

• To encourage the local Maratha warriors to fight independently against the Mughals, Ramchandra Pant adopted a new policy to officially reward pieces of land (Vatans) in exchange for military service. Turn out the Mughals and own the land was the pronouncement. This mercenary policy went against Shivaji's will, but Ramchandra Pant saw no alternative given the changed circumstances.

• Independent Maratha warlords were encouraged to cross the Maharashtra border and to invade Mughal areas in response to Mughal invasion. Nemaji Shinde and Chimnaji Damodar were the first warlords to successfully respond to this strategy.

• Appealing to Mughal greed, Maratha forts were traded to the Mughals for large sums. Once the forts were well equipped by the Mughals, the forts were re-captured by Maratha forces.

These strategies proved to be extremely effective against the Mughal Empire.

Later career

In 1698, after Rajaram's return from Gingee, Ramchandra Pant voluntarily stepped down from the post of Imperial Regent.

In 1700, after Rajaram's death, Queen Tarabai once again delegated enormous wartime powers to Ramchandra Pant. Both of them continued to fight against the Mughal power in India. At the time of Aurangzeb's death in 1707, the Marathas had become extremely powerful and the Mughal Empire was on the verge of total devastation.

After Shahu's release from the Mughal camp, most of the Maratha generals defected from Tarabai and joined him. As a result, Tarabai was forced to leave the capital at Satara, fleeing to Panhala fort. Ramchandra Pant, however, strongly supported Tarabai at the time and worked as the Senior Minister for her son Shivaji II.

In 1714, Rajasbai instigated a coup against Tarabai and her son Shivaji II and installed her own son Sambhaji II on the Kolhapur throne. Modern-day scholars generally conclude that Ramchandra Pant was behind this conspiracy as he was appointed by Sambhaji II to the Imperial Regency immediately thereafter. It is speculated that Ramchandra Pant and his supporters were not satisfied with Tarabai's treatment of her peerage.

Later life

On the request of Sambhaji II, Ramchandra Pant wrote the Adnyapatra (also spelled Ajnapatra), a standard code of civil and military administration for the Maratha Empire. It can be compared to Kautilya's Arthashastra.

In 1716, Ramchandra Pant died at the age of 66. A monument dedicated to his life and valiant effort in fighting against the Mughal invaders is located at Panhala fort. His heirs still live near Fort Gaganbawada to this day — a gift to Ramchandra Pant for his great contribution to Maratha power.

Founder of Gaganbavada Jahagir

Pant Amatya Wada at Gaganbavada

The descendants of Ramchandra Pant Amatya were awarded the Jahagir of Gagan Bavda, the hilly region on the hilltops of the Konkan and the Konkan area. This was the largest Jahagir in Kolhapur state with an area of 243 square miles. The Jahagir extended from Mutukeshwar near Kolhapur almost touching the Mumbai Goa highway of today. The area in Konkan was managed from here. More than a mere Jahagir, it was a Feudatory kingdom with its own revenue Department, Police Force, Judicial and Criminal Courts etc.

The Main Jahagir Offices were situated in Gagan Bavda where the police force, Revenue departments and Courts were situated in the Rajwada area.

The Jahagirdars of Bavda were given the title of Raja by Shahu along with 3 other Jaghirdars of Kolhapur namely Kagal (Ghatges), Vishalgad (Pratinidhis) and Kapashi (Ghorpades). The Bavda Jahagir though the biggest in area, was not the one with highest income due to people living in hilly area and scattered population. The Jahagirdar's of Bavda in spite of natural odds undertook many welfare schemes for the subjects in their area.

The Jahagir was abolished after independence and a privy purse was given to the Jahagirdar's until 1975.

The present descendants live in Tararbai Park, area of Kolhapur in Maharashtra state.

Geography of Bavda Jahagir (Sanstha Bavda):

Boundaries on the east, North and south of Bavda is the Kolhapur state. On the west, the Jahagir had a border with Ratnagiri district. Some of the towns in the Jahagir were also located outside the boundaries. The east west length is approx 40 miles and width approx 25 miles. The total area being 243 square miles. It was divided between Konkan Area and area on top of the Sahyadri Ghats. Most of the area is dense forests. The height of the konkan area from the sea level is 450 feet and the upper area height from the sea level is 200 feet. The Sahyadri mountain ranges reach up to a height of 3400 feet.

The forts of Gagangad and Shivgad were situated in Gagan Bavda Jahagir. In 1846, the old buildings on the Gagangad fort were demolished after which there was no habitation on the forts, until the time Gagangiri Maharaj built an Ashram on Gagangad fort.

The crops mainly cultivated are Sugarcane, rice, sunflower Maize etc. The fruits which are natural to the region are Jackfruit, Jambhul, karvanda etc.

Gaganbavada Fort

Gaganbavda fort was built by Raja Bhoj from around 1178 to 1209 A.D. The height of the fort from sea level is 2244 feet on The western Sahyadri Mountain ranges. The fort had buildings earlier which have demolished.

Gagan Bavda fort came into the Maratha's control in the year 1660. It was given to Ramchandra Pant Amatya's father Nilo Sondev. For some time, it was captured by the Adilshahi forces but came back into the Maratha's fold in 1689. After the Maghals held Sambhaji, it went in to their hands. Ramchandra Pant Amatya captured it and brought it under Swaraj in 1700 and which remained in The Bavda Jahagir till independence.

At the time Bavda Jahagir extended up to Malvan and Vijaydurg and had a cavalry of 25000.

References

1. Shivaji, the great Maratha, Volume 2, H. S. Sardesai, Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd, 2002, ISBN 81-7755-286-4, ISBN 978-81-7755-286-7

Bibliography

• Dahiya, Poonam Dalal (2017). ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL INDIA. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9789352606733.

External links

• ‘Marathi Riyasat’ (Marathi) by Govind Sakharam Sardesai

• 'The New History of Marathas' by Govind Sakharam Sardesai

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/24/21

Ramchandra Pant Amatya Bavdekar

Ramchandra Pant Amatya Painting made from earlier statue. Artist Swapnil Patil.

Flag of the Maratha Empire.svgAmatya of the Maratha Empire

In office: 1674–1689

Monarch Chhatrapati Shivaji I; Sambhaji

Preceded by: position established

Succeeded by: Bahiroji Pingale

Regent of the Maratha Empire

In office: 1689–1708

Monarch: Sambhaji; Rajaram; Shivaji II; Sambhaji II

Preceded by: Moreshvar Pingale

Succeeded by: Bahiroji Pingale

Personal details

Born: 1650, Kolwan (Pune District, Maharashtra)

Died: 1716, Panhala (Kolhapur District, Maharashtra)

Spouse(s): Janakibai

Ramchandra Neelkanth Bawadekar (1650–1716), also known as Ramchandra Pant Amatya, served on the Council of 8 (Ashta Pradhan) as the Finance Minister (Amatya) to Emperor (Chhatrapati) Shivaji dating from 1674 to 1680.[1] He then served as the Imperial Regent to four later emperors, namely Sambhaji, Rajaram, Shivaji II and Sambhaji II. He authored the Adnyapatra, a famous code of civil and military administration, and is renowned as one of the greatest civil administrators, diplomats and military strategists of the Maratha Empire.

Early life

Ramchandra Pant was born in a Deshastha Brahmin family in approximately 1650. He was the youngest son of Neelkanth Sondeo Bahutkar (more popularly known as Nilo Sondeo), who had risen from a local revenue collection post (Kulkarni) to the post of Minister in the court of Shivaji.

His family came from the village of Kolwan; near Kalyan Bhiwandi. Ramchandra Pant's grandfather Sonopant and uncle Abaji Sondeo were in the close circle of Shivaji. The Bahutkar family was closely associated with Samarth Ramdas, the spiritual guru of Shivaji. Samarth Ramdas is believed to be the one who named the newly born child as Ramchandra.

Early career

Before 1672, Ramchandra Pant was engaged in various clerical jobs in Shivaji's administration. In 1672, he and his elder brother Narayan were both promoted to the post of Revenue Minister (Mujumdar) by Shivaji. In 1674, at the coronation ceremony, the post of Mujumdar was renamed as Amatya and the title was solely bestowed upon Ramchandra Pant. He worked in this capacity until 1678. On his death bed, Shivaji named him as one among six pillars of the Maratha Empire that would save the kingdom in difficult times.

After Shivaji's death in 1680, Sambhaji became ruler of the Maratha Empire, and Ramchandra Pant continued with his administration in various posts. Among other duties, Ramchandra Pant was sent to Prince Akbar, Aurangzeb's rebel son, for negotiations and, in 1685, Sambhaji also deployed him as an envoy to Vijapur for certain sensitive talks.

Amatya of 5 Chhatrapaties

Ramchandra Pant Amatya was the only person (Amatya) who dedicatedly served The Maratha Swarajya under 5 Chhatrapati's in a row. When the Marathi empire was in trouble he used his wisdom, dedication to the throne and even force as needed to keep the empire and its Swarajya safe.

During the coronation of Shivaji, Ramchandra Pant Amatya was the youngest Pradhan of all the Asthapradhan's existing at that time. Thereafter, during the reign of Sambhaji, Rajaram, Maharani Tarabai and (Kolhapur's first ruler) Sambhaji Raje, Pant Amatya always held a prominent positions. As Riyasatkar(s) rightly said that ‘ever since the time of Shivaji Maharaj, Ramchandra Pant Amatya was the only person in the history of the Marathas who seems to have dedicatedly served the throne.’ Ramchandra Pant Amatya has laid down all the experiences encountered by him, while serving the throne in his book Rajniti (Adnyapatra). The said book is a testament to his dedication and service to the throne of Chatrapati's and Hindavi Swarajya.

The forefathers of Ramchandra Pant Amatya had close relations with the Bhosle Gharana even before the establishment of Swarajya. Before the coronation of Shivaji, Ramchandra Pant Amatya's father used to participate in various initiatives undertaken by Shivaji. Ramchandra Pant Amatya subsequently carried forward this (his father's) tradition with even more impact. Ramchandra Pant Amatya took the lead when it came to the protection of the Swarajya. Being impressed by his efforts, Shivaji included Ramchandra Pant as Amatya in his First Ashta Pradhan mandal i.e. Council of Ministers. This, in itself portrays the qualities that Ramchandra Pant Amatya possessed. During the coronation ceremony of Shivaji, Pant was included as Amatya. He must’ve been 22–23 years old then. Before the coronation, a Pradhan Mandal was appointed by Maharaj in the year 1662 which included Ramchandra Pant's father Neelkanth Sondev as Maharaj's Amatya. This legacy was carried forward, as after the death of Neelkanth Sondev his son Ramchandra Pant was appointed as Maharaj's Amatya.

According to the information provided by the Bakharkar(s), Ramchandra Pant Amatya was one of the very few people present when Shivaji was on his death bed at Raigad. Shivaji had named a few people who had the ability protect the Swarajya after his demise. Ramchandra Pant Amatya was one of them. During the Reign of Sambhaji, Ramchandra Pant Amatya was given an important position. (Period of 1680 to 1685)

Fight for Freedom

After the unfortunate demise of Sambhaji, the Maratha Empire was in great trouble. Aurangzeb had taken a vow to defeat the Maratha empire at any cost, and with that motive, he attacked many forts of the Marathas with a huge army. Sadness prevailed all over the Maratha Empire. In this situation, Ramchandra Pant Amatya stood up and acted with a lot of patience. This was the era of the freedom struggle of the Maratha empire. Ramchandra Pant Amatya did every thing he could to keep the royal family and the Maratha empire safe and endure the struggle of the troubled times. Ramchandra Pant Amatya, Santaji Ghorpade, Dhanaji Jadhav, Parshurampant Pant-Pratinidhi were the major contributors to the struggle for freedom.[citation needed]

Rajaram Maharaj's stay in Gingi ended in 1697. He returned to Maharashtra. However, Rajaram Maharaj died in 1700 when he was at Fort Sinhagad. The Maratha empire was in trouble again. Ramchandra Pant Amatya did everything he could to save the Maratha Empire from the trouble and he succeeded. This was no mean achievement. Ramchandra Pant had paid a visit to Rajaram Maharaj when he was on his death bed at Sinhagad fort. Pant had sensed the inevitable. He wrote letters to many Sardars and informed them of the dire situation and brought to their notice, the need to protect the Empire.

After the death of Rajaram Maharaj, Aurangzeb started attacking with even more force. He thought that now, he could easily defeat the Maratha empire as there was no King. He planned to take over the entire empire. But he was wrong. Ramchandra Pant, Dhanaji Jadhav, Parshuram Pant Pratinidhi along with thousands of soldiers loyal and dedicated to the throne resolved to defend their Empire. They fought with Aurangzeb for seven years continuously, that is from 1700 to 1707. Eventually, Aurangzeb admitted defeat and subsequently died in Ahmednagar. This struggle for 7 continuous years was a period with innumerable difficulties and troubles for the Marathas. The leadership of Maharani Tarabai and the wisdom of Ramchandra Pant had played a vital role in the protection of the Swarajya in these 7 years. Tarabai wanted her son Shivaji II on the Maratha throne but Ramchandra Pant wanted to wait for Prince Shahu to return. But he did not pursue it beyond a point. He decided to be loyal to the Kolhapur throne. Tararani knew about Ramchandra Pant's capabilities and qualities. In every time of peril, he stood behind the Maratha throne like a mountain. Tarabai has in a letter to his son Bhagwantrao acknowledged his greatness. She says, "Ramchandra Pant served the Maratha kingdom with great loyalty. He restored an almost finished Swarajya and made a great name for himself ".[citation needed]

It is said that Ramchandra Pant Amatya was behind the bloodless coup that led to Rajasbai's son Sambhaji being crowned as The Chatrapati in 1713-1714. He felt it necessary as the Kolhapur Kingdom was heading towards a different path. There seems to be no ulterior motive behind this coup. He crowned Sambhaji as the Chatrapati and soon went in the background. As Sambhaji was only 16–17 years old he would naturally look up to Ramchandra Pant Amatya for guidance. Shortly after Ramchandra Pant Amatya died. There is some confusion about the date of his death but most historians assume it to be somewhere in February 1716.[citation needed]

A Warrior and A Statesman

Ramchandra Pant Amatya was also a warrior as he was a statesman. He is known to lead many wars. Moghul historians mention that when Aurangzeb's grandson had invaded Panhala in 1693 Ramchandra Pant along with Pratinidhi launched a heavy attack on the Mughal forces. A Farsi historian notes that Ramchandra Pant was the head of Konkan army in 1699 and attacked them with all his might. His guns were blazing with all their might and a mighty war ensued.[citation needed]

A Portuguese Killedar has mentioned that on 22 February 1701 Ramchandra Pant along with 20,000 Maratha's attacked Dandya's Siddi Yakubkhan.

Adnyapatra

Coat of Arms of Pant Amatya Gaganbavada

Ramchandra Pant Amatya is the writer of the First book on Politics in Maratha history "AdnyaPatra". This main topics refer to

1. The King and his duties ways of governance,

2. How revenue is important for the State

3. Importance of the Army and Importance of scholars and experts in all fields

4. Education of the Princes.

5. Importance of a Pradhan i.e. Prime Minister and his duties

6. Policies regarding foreigners i.e. British, French etc.

7. Policy regarding your judicatories

8. Importance of forts.

9. he who has the Navy rules the seas,

10. Policy regarding natural resources etc.

It is said that it outlines the theories and way of ruling of Shivaji. The book is said to be of such high stature that it can be compared to Kautilya's Arthashastra.

It is said that the book still holds relevance in today's time and can be a guide for a person in the administration of a state, such is the richness of his thoughts more than 300 years back.

Contribution to Maratha War of Independence

In 1689, at the time of Sambhaji's assassination by Aurangzeb, Ramchandra Pant was deployed at Fort Vishalgad. In consultation with Sambhaji's queen, Yesubai, who was located at Fort Raigad along with Rajaram and her son Shahu, he decided to send Rajaram to Fort Gingee (in current-day Tamil Nadu) to divide the battlefield. Subsequently, Rajaram was brought to Panhala fort and was secretly sent to Gingee. Before leaving for Gingee, Rajaram conferred on Ramchandra Pant the title of Imperial Regent (Hukumat Panah).

Thereafter, with the aid of generals Santaji Ghorpade, Dhanaji Jadhav, Parshuram Pant Pratinidhi, and Shankaraji Narayan Gandekar, Ramchandra Pant launched a great retaliatory war against the Mughal Empire.

Wartime strategies

• To encourage the local Maratha warriors to fight independently against the Mughals, Ramchandra Pant adopted a new policy to officially reward pieces of land (Vatans) in exchange for military service. Turn out the Mughals and own the land was the pronouncement. This mercenary policy went against Shivaji's will, but Ramchandra Pant saw no alternative given the changed circumstances.

• Independent Maratha warlords were encouraged to cross the Maharashtra border and to invade Mughal areas in response to Mughal invasion. Nemaji Shinde and Chimnaji Damodar were the first warlords to successfully respond to this strategy.

• Appealing to Mughal greed, Maratha forts were traded to the Mughals for large sums. Once the forts were well equipped by the Mughals, the forts were re-captured by Maratha forces.

These strategies proved to be extremely effective against the Mughal Empire.

Later career

In 1698, after Rajaram's return from Gingee, Ramchandra Pant voluntarily stepped down from the post of Imperial Regent.

In 1700, after Rajaram's death, Queen Tarabai once again delegated enormous wartime powers to Ramchandra Pant. Both of them continued to fight against the Mughal power in India. At the time of Aurangzeb's death in 1707, the Marathas had become extremely powerful and the Mughal Empire was on the verge of total devastation.

After Shahu's release from the Mughal camp, most of the Maratha generals defected from Tarabai and joined him. As a result, Tarabai was forced to leave the capital at Satara, fleeing to Panhala fort. Ramchandra Pant, however, strongly supported Tarabai at the time and worked as the Senior Minister for her son Shivaji II.

In 1714, Rajasbai instigated a coup against Tarabai and her son Shivaji II and installed her own son Sambhaji II on the Kolhapur throne. Modern-day scholars generally conclude that Ramchandra Pant was behind this conspiracy as he was appointed by Sambhaji II to the Imperial Regency immediately thereafter. It is speculated that Ramchandra Pant and his supporters were not satisfied with Tarabai's treatment of her peerage.

Later life

On the request of Sambhaji II, Ramchandra Pant wrote the Adnyapatra (also spelled Ajnapatra), a standard code of civil and military administration for the Maratha Empire. It can be compared to Kautilya's Arthashastra.

In 1716, Ramchandra Pant died at the age of 66. A monument dedicated to his life and valiant effort in fighting against the Mughal invaders is located at Panhala fort. His heirs still live near Fort Gaganbawada to this day — a gift to Ramchandra Pant for his great contribution to Maratha power.

Founder of Gaganbavada Jahagir

Pant Amatya Wada at Gaganbavada

The descendants of Ramchandra Pant Amatya were awarded the Jahagir of Gagan Bavda, the hilly region on the hilltops of the Konkan and the Konkan area. This was the largest Jahagir in Kolhapur state with an area of 243 square miles. The Jahagir extended from Mutukeshwar near Kolhapur almost touching the Mumbai Goa highway of today. The area in Konkan was managed from here. More than a mere Jahagir, it was a Feudatory kingdom with its own revenue Department, Police Force, Judicial and Criminal Courts etc.

The Main Jahagir Offices were situated in Gagan Bavda where the police force, Revenue departments and Courts were situated in the Rajwada area.

The Jahagirdars of Bavda were given the title of Raja by Shahu along with 3 other Jaghirdars of Kolhapur namely Kagal (Ghatges), Vishalgad (Pratinidhis) and Kapashi (Ghorpades). The Bavda Jahagir though the biggest in area, was not the one with highest income due to people living in hilly area and scattered population. The Jahagirdar's of Bavda in spite of natural odds undertook many welfare schemes for the subjects in their area.

The Jahagir was abolished after independence and a privy purse was given to the Jahagirdar's until 1975.

The present descendants live in Tararbai Park, area of Kolhapur in Maharashtra state.

Geography of Bavda Jahagir (Sanstha Bavda):

Boundaries on the east, North and south of Bavda is the Kolhapur state. On the west, the Jahagir had a border with Ratnagiri district. Some of the towns in the Jahagir were also located outside the boundaries. The east west length is approx 40 miles and width approx 25 miles. The total area being 243 square miles. It was divided between Konkan Area and area on top of the Sahyadri Ghats. Most of the area is dense forests. The height of the konkan area from the sea level is 450 feet and the upper area height from the sea level is 200 feet. The Sahyadri mountain ranges reach up to a height of 3400 feet.

The forts of Gagangad and Shivgad were situated in Gagan Bavda Jahagir. In 1846, the old buildings on the Gagangad fort were demolished after which there was no habitation on the forts, until the time Gagangiri Maharaj built an Ashram on Gagangad fort.

The crops mainly cultivated are Sugarcane, rice, sunflower Maize etc. The fruits which are natural to the region are Jackfruit, Jambhul, karvanda etc.

Gaganbavada Fort

Gaganbavda fort was built by Raja Bhoj from around 1178 to 1209 A.D. The height of the fort from sea level is 2244 feet on The western Sahyadri Mountain ranges. The fort had buildings earlier which have demolished.

Gagan Bavda fort came into the Maratha's control in the year 1660. It was given to Ramchandra Pant Amatya's father Nilo Sondev. For some time, it was captured by the Adilshahi forces but came back into the Maratha's fold in 1689. After the Maghals held Sambhaji, it went in to their hands. Ramchandra Pant Amatya captured it and brought it under Swaraj in 1700 and which remained in The Bavda Jahagir till independence.

At the time Bavda Jahagir extended up to Malvan and Vijaydurg and had a cavalry of 25000.

References

1. Shivaji, the great Maratha, Volume 2, H. S. Sardesai, Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd, 2002, ISBN 81-7755-286-4, ISBN 978-81-7755-286-7

Bibliography

• Dahiya, Poonam Dalal (2017). ANCIENT AND MEDIEVAL INDIA. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 9789352606733.

External links

• ‘Marathi Riyasat’ (Marathi) by Govind Sakharam Sardesai

• 'The New History of Marathas' by Govind Sakharam Sardesai

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36180

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Freda Bedi Cont'd (#3)

Part 1 of 2

Chapter Six: The Nation and Its Women: The Paradox of the Women's Question, Excerpt From The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories

by Partha Chatterjee

© 1993 by Princeton University Press

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

CHAPTER SIX: The Nation and Its Women

THE PARADOX OF THE WOMEN'S QUESTION

The "women's question" was a central issue in the most controversial debates over social reform in early and mid-nineteenth-century Bengal— the period of its so-called renaissance. Rammohan Roy's historical fame is largely built around his campaign against the practice of the immolation of widows, Vidyasagar's around his efforts to legalize widow remarriage and abolish Kulin polygamy; the Brahmo Samaj was split twice in the 1870s over questions of marriage laws and the "age of consent." What has perplexed historians is the rather sudden disappearance of such issues from the agenda of public debate toward the close of the century. From then onward, questions regarding the position of women in society do not arouse the same degree of public passion and acrimony as they did only a few decades before. The overwhelming issues now are directly political ones—concerning the politics of nationalism.

How are we to interpret this change? Ghulam Murshid states the problem in its most obvious, straightforward form.1 If one takes seriously, that is to say, in their liberal, rationalist and egalitarian content, the mid-nineteenth-century attempts in Bengal to "modernize" the condition of women, then what follows in the period of nationalism must be regarded as a clear retrogression. Modernization began in the first half of the nineteenth century because of the penetration of Western ideas. After some limited success, there was a perceptible decline in the reform movements as popular attitudes toward them hardened. The new politics of nationalism "glorified India's past and tended to defend everything traditional"; all attempts to change customs and life-styles began to be seen as the aping of Western manners and were thereby regarded with suspicion. Consequently, nationalism fostered a distinctly conservative attitude toward social beliefs and practices. The movement toward modernization was stalled by nationalist politics.

This critique of the social implications of nationalism follows from rather simple and linear historicist assumptions. Murshid not only accepts that the early attempts at social reform were impelled by the new nationalist and progressive ideas imported from Europe, he also presumes that the necessary historical culmination of such reforms in India ought to have been, as in the West, the full articulation of liberal values in social institutions and practices. From these assumptions, a critique of nationalist ideology and practices is inevitable, the same sort of critique as that of the colonialist historians who argue that Indian nationalism was nothing but a scramble for sharing political power with the colonial rulers; its mass following only the successful activization of traditional patron-client relationships; its internal debates the squabbles of parochial factions; and its ideology a garb for xenophobia and racial exclusiveness.

Clearly, the problem of the diminished importance of the women's question in the period of nationalism deserves a different answer from the one given by Murshid. Sumit Sarkar has argued that the limitations of nationalist ideology in pushing forward a campaign for liberal and egalitarian social change cannot be seen as a retrogression from an earlier radical reformist phase.2 Those limitations were in fact present in the earlier phase as well. The renaissance reformers, he shows, were highly selective in their acceptance of liberal ideas from Europe. Fundamental elements of social conservatism such as the maintenance of caste distinctions and patriarchal forms of authority in the family, acceptance of the sanctity of the šástra (scriptures), preference for symbolic rather than substantive changes in social practices—all these were conspicuous in the reform movements of the early and mid-nineteenth century.

Following from this, we could ask: How did the reformers select what they wanted? What, in other words, was the ideological sieve through which they put the newly imported ideas from Europe? If we can reconstruct this framework of the nationalist ideology, we will be in a far better position to locate where exactly the women's question fitted in with the claims of nationalism. We will find, if I may anticipate my argument in this chapter, that nationalism did in fact provide an answer to the new social and cultural problems concerning the position of women in "modern" society, and that this answer was posited not on an identity but on a difference with the perceived forms of cultural modernity in the West. I will argue, therefore, that the relative unimportance of the women's question in the last decades of the nineteenth century is to be explained not by the fact that it had been censored out of the reform agenda or overtaken by the more pressing and emotive issues of political struggle. The reason lies in nationalism's success in situating the "women's question" in an inner domain of sovereignty, far removed from the arena of political contest with the colonial state. This inner domain of national culture was constituted in the light of the discovery of "tradition."

THE WOMEN'S QUESTION IN "TRADITION"

Apart from the characterization of the political condition of India preceding the British conquest as a state of anarchy, lawlessness, and arbitrary despotism, a central element in the ideological justification of British colonial rule was the criticism of the "degenerate and barbaric" social customs of the Indian people, sanctioned, or so it was believed, by the religious tradition. Alongside the project of instituting orderly, lawful, and rational procedures of governance, therefore, colonialism also saw itself as performing a "civilizing mission." In identifying this tradition as "degenerate and barbaric," colonialist critics invariably repeated a long list of atrocities perpetrated on Indian women, not so much by men or certain classes of men, but by an entire body of scriptural canons and ritual practices that, they said, by rationalizing such atrocities within a complete framework of religious doctrine, made them appear to perpetrators and sufferers alike as the necessary marks of right conduct. By assuming a position of sympathy with the unfree and oppressed womanhood of India, the colonial mind was able to transform this figure of the Indian woman into a sign of the inherently oppressive and unfree nature of the entire cultural tradition of a country.

Take, for example, the following account by an early nineteenth-century British traveler in India:

An effervescent sympathy for the oppressed is combined in this breathless prose with a total moral condemnation of a tradition that was seen to produce and sanctify these barbarous customs. And of course it was suttee that came to provide the most clinching example in this rhetoric of condemnation—"the first and most criminal of their customs," as William Bentinck, the governor-general who legislated its abolition, described it. Indeed, the practical implication of the criticism of Indian tradition was necessarily a project of "civilizing" the Indian people: the entire edifice of colonialist discourse was fundamentally constituted around this project.

Of course, within the discourse thus constituted, there was much debate and controversy about the specific ways in which to carry out this project. The options ranged from proselytization by Christian missionaries to legislative and administrative action by the colonial state to a gradual spread of enlightened Western knowledge. Underlying each option was the liberal colonial idea that in the end, Indians themselves must come to believe in the unworthiness of their traditional customs and embrace the new forms of civilized and rational social order.

I spoke, in chapter 2, of some of the political strategies of this civilizing mission. What must be noted here is that the so-called women's question in the agenda of Indian social reform in the early nineteenth century was not so much about the specific condition of women within a specific set of social relations as it was about the political encounter between a colonial state and the supposed "tradition" of a conquered people—a tradition that, as Lata Mani has shown in her study of the abolition of satidaha (immolation of widows),4 was itself produced by colonialist discourse. It was colonialist discourse that, by assuming the hegemony of Brahmanical religious texts and the complete submission of all Hindus to the dictates of those texts, defined the tradition that was to be criticized and reformed. Indian nationalism, in demarcating a political position opposed to colonial rule, took up the women's question as a problem already constituted for it: namely, as a problem of Indian tradition.

THE WOMEN'S QUESTION IN NATIONALISM

I described earlier the way nationalism separated the domain of culture into two spheres—-the material and the spiritual. The claims of Western civilization were the most powerful in the material sphere. Science, technology, rational forms of economic organization, modern methods of statecraft—these had given the European countries the strength to subjugate the non-European people and to impose their dominance over the whole world. To overcome this domination, the colonized people had to learn those superior techniques of organizing material life and incorporate them within their own cultures. This was one aspect of the nationalist project of rationalizing and reforming the traditional culture of their people. But this could not mean the imitation of the West in every aspect of life, for then the very distinction between the West and the East would vanish—the self-identity of national culture would itself be threatened. In fact, as Indian nationalists in the late nineteenth century argued, not only was it undesirable to imitate the West in anything, other than the material aspects of life, it was even unnecessary to do so, because in the spiritual domain, the East was superior to the West. What was necessary was to cultivate the material techniques of modern Western civilization while retaining and strengthening the distinctive spiritual essence of the national culture. This completed the formulation of the nationalist project, and as an ideological justification for the selective appropriation of Western modernity, it continues to hold sway to this day.

The discourse of nationalism shows that the material/spiritual distinction was condensed into an analogous, but ideologically far more powerful, dichotomy: that between the outer and the inner. The material domain, argued nationalist writers, lies outside us—a mere external that influences us, conditions us, and forces us to adjust to it. Ultimately, it is unimportant. The spiritual, which lies within, is our true self; it is that which is genuinely essential. It followed that as long as India took care to retain the spiritual distinctiveness of its culture, it could make all the compromises and adjustments necessary to adapt itself to the requirements of a modern material world without losing its true identity. This was the key that nationalism supplied for resolving the ticklish problems posed by issues of social reform in the nineteenth century.

[b][size=110]Applying the inner/outer distinction to the matter of concrete day-to-day living separates the social space into ghar and bahir, the home and the world. The world is the external, the domain of the material; the home represents one's inner spiritual self, one's true identity. The world is a treacherous terrain of the pursuit of material interests, where practical considerations reign supreme. It is also typically the domain of the male. The home in its essence must remain unaffected by the profane activities of the material world—and woman is its representation. And so one gets an identification of social roles by gender to correspond with the separation of the social space into ghar and bahir.

Chapter Six: The Nation and Its Women: The Paradox of the Women's Question, Excerpt From The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories

by Partha Chatterjee

© 1993 by Princeton University Press

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Highlights:

I described earlier the way nationalism separated the domain of culture into two spheres—-the material and the spiritual. The claims of Western civilization were the most powerful in the material sphere. Science, technology, rational forms of economic organization, modern methods of statecraft—these had given the European countries the strength to subjugate the non-European people and to impose their dominance over the whole world. To overcome this domination, the colonized people had to learn those superior techniques of organizing material life and incorporate them within their own cultures. This was one aspect of the nationalist project of rationalizing and reforming the traditional culture of their people. But this could not mean the imitation of the West in every aspect of life, for then the very distinction between the West and the East would vanish—the self-identity of national culture would itself be threatened. In fact, as Indian nationalists in the late nineteenth century argued, not only was it undesirable to imitate the West in anything, other than the material aspects of life, it was even unnecessary to do so, because in the spiritual domain, the East was superior to the West. What was necessary was to cultivate the material techniques of modern Western civilization while retaining and strengthening the distinctive spiritual essence of the national culture. This completed the formulation of the nationalist project, and as an ideological justification for the selective appropriation of Western modernity, it continues to hold sway to this day.

The discourse of nationalism shows that the material/spiritual distinction was condensed into an analogous, but ideologically far more powerful, dichotomy: that between the outer and the inner. The material domain, argued nationalist writers, lies outside us—a mere external that influences us, conditions us, and forces us to adjust to it. Ultimately, it is unimportant. The spiritual, which lies within, is our true self; it is that which is genuinely essential. It followed that as long as India took care to retain the spiritual distinctiveness of its culture, it could make all the compromises and adjustments necessary to adapt itself to the requirements of a modern material world without losing its true identity. This was the key that nationalism supplied for resolving the ticklish problems posed by issues of social reform in the nineteenth century.

Applying the inner/outer distinction to the matter of concrete day-to-day living separates the social space into ghar and bahir, the home and the world. The world is the external, the domain of the material; the home represents one's inner spiritual self, one's true identity. The world is a treacherous terrain of the pursuit of material interests, where practical considerations reign supreme. It is also typically the domain of the male. The home in its essence must remain unaffected by the profane activities of the material world—and woman is its representation. And so one gets an identification of social roles by gender to correspond with the separation of the social space into ghar and bahir….

The world was where the European power had challenged the non-European peoples and, by virtue of its superior material culture, had subjugated them. But, the nationalists asserted, it had failed to colonize the inner, essential, identity of the East, which lay in its distinctive, and superior, spiritual culture. Here the East was undominated, sovereign, master of its own fate. For a colonized people, the world was a distressing constraint, forced upon it by the fact of its material weakness. It was a place of oppression and daily humiliation, a place where the norms of the colonizer had perforce to be accepted. It was also the place, as nationalists were soon to argue, where the battle would be waged for national independence. The subjugated must learn the modern sciences and arts of the material world from the West in order to match their strengths and ultimately overthrow the colonizer. But in the entire phase of the national struggle, the crucial need was to protect, preserve, and strengthen the inner core of the national culture, its spiritual essence. No encroachments by the colonizer must be allowed in that inner sanctum. In the world, imitation of and adaptation to Western norms was a necessity; at home, they were tantamount to annihilation of one's very identity…

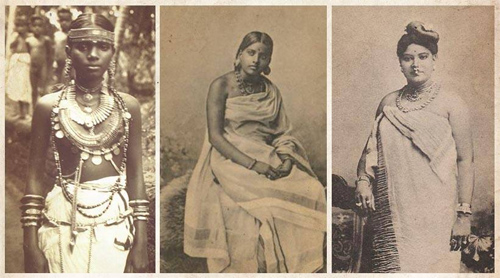

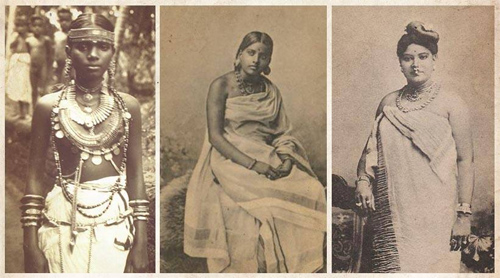

It is striking how much of the literature on women in the nineteenth century concerns the threatened Westernization of Bengali women. This theme was taken up in virtually every form of written, oral, and visual communication—from the ponderous essays of nineteenth-century moralists, to novels, farces, skits and jingles, to the paintings of the patua (scroll painters)…. To ridicule the idea of a Bengali woman trying to imitate the ways of a memsaheb (and it was very much an idea, for it is hard to find historical evidence that even in the most Westernized families of Calcutta in the mid-nineteenth century there were actually any women who even remotely resembled these gross caricatures) was a sure recipe calculated to evoke raucous laughter and moral condemnation in both male and female audiences. It was, of course, a criticism of manners, of new items of clothing such as the blouse, the petticoat, and shoes (all, curiously, considered vulgar, although they clothed the body far better than the single length of sari that was customary for Bengali women, irrespective of wealth and social status, until the middle of the nineteenth century), of the use of Western cosmetics and jewelry, of the reading of novels, of needlework (considered a useless and expensive pastime), of riding in open carriages. What made the ridicule stronger was the constant suggestion that the Westernized woman was fond of useless luxury and cared little for the well-being of the home….

Yet it was clear that a mere restatement of the old norms of family life would not suffice; they were breaking down because of the inexorable force of circumstance. New norms were needed, which would be more appropriate to the external conditions of the modern world and yet not a mere imitation of the West.

What were the principles by which these new norms could be constructed?

Bhudeb supplies the characteristic nationalist answer. In an essay entitled "Modesty," he talks of the natural and social principles that provide the basis for the feminine virtues. Modesty, or decorum in manner and conduct, he says, is a specifically human trait; it does not exist in animal nature. It is human aversion to the purely animal traits that gives rise to virtues such as modesty. In this aspect, human beings seek to cultivate in themselves, and in their civilization, spiritual or godlike qualities wholly opposed to the forms of behavior which prevail in animal nature. Further, within the human species, women cultivate and cherish these godlike qualities far more than men. Protected to a certain extent from the purely material pursuits of securing a livelihood in the external world, women express in their appearance and behavior the spiritual qualities that are characteristic of civilized and refined human society…

The point is then hammered home:Those who laid down our religious codes discovered the inner spiritual quality which resides within even the most animal pursuits which humans must perform, and thus removed the animal qualities from those actions. This has not happened in Europe. Religion there is completely divorced from [material] life. Europeans do not feel inclined to regulate all aspects of their life by the norms of religion; they condemn it as clericalism.'... In the Arya system there is a preponderance of spiritualism, in the European system a preponderance of material pleasure. In the Arya system, the wife is a goddess. In the European system, she is a partner and companion….

The new woman defined in this way was subjected to a new patriarchy. In fact, the social order connecting the home and the world in which nationalists placed the new woman was contrasted not only with that of modern Western society; it was explicitly distinguished from the patriarchy of indigenous tradition, the same tradition that had been put on the dock by colonial interrogators. Sure enough, nationalism adopted several elements from tradition as marks of its native cultural identity, but this was now a "classicized" tradition—reformed, reconstructed, fortified against charges of barbarism and irrationality.

The new patriarchy was also sharply distinguished from the immediate social and cultural condition in which the majority of the people lived, for the "new" woman was quite the reverse of the "common" woman, who was coarse, vulgar, loud, quarrelsome, devoid of superior moral sense, sexually promiscuous, subjected to brutal physical oppression by males. Alongside the parody of the Westernized woman, this other construct is repeatedly emphasized in the literature of the nineteenth century through a host of lower-class female characters who make their appearance in the social milieu of the new middle class—maidservants, washer women, barbers, peddlers, procuresses, prostitutes. It was precisely this degenerate condition of women that nationalism claimed it would reform, and it was through these contrasts that the new woman of nationalist ideology was accorded a status of cultural superiority to the Westernized women of the wealthy parvenu families spawned by the colonial connection as well as to common women of the lower classes. Attainment by her own efforts of a superior national culture was the mark of woman's newly acquired freedom. This was the central ideological strength of the nationalist resolution of the women's question….

Formal education became not only acceptable but, in fact, a requirement for the new bhadramahila (respectable woman) when it was demonstrated that it was possible for a woman to acquire the cultural refinements afforded by modern education without jeopardizing her place at home, that is, without becoming a memsaheb… Indeed, the achievement was marked by claims of cultural superiority in several different aspects: superiority over the Western woman for whom, it was believed, education meant only the acquisition of material skills to compete with men in the outside world and hence a loss of feminine (spiritual) virtues; superiority over the preceding generation of women in their own homes who had been denied the opportunity of freedom by an oppressive and degenerate social tradition; and superiority over women of the lower classes who were culturally incapable of appreciating the virtues of freedom….

Recent historians of a liberal persuasion have often been somewhat embarrassed by the profuse evidence of women writers of the nineteenth century, including those at the forefront of the reform movements in middle-class homes, justifying the importance of the so-called feminine virtues. Radharani Lahiri, for instance, wrote in 1875: "Of all the subjects that women might learn, housework is the most important. . .. Whatever knowledge she may acquire, she cannot claim any reputation unless she is proficient in housework." Others spoke of the need for an educated woman to develop such womanly virtues as chastity, self-sacrifice, submission, devotion, kindness, patience, and the labors of love. The ideological point of view from which such protestations of "femininity" (and hence the acceptance of a new patriarchal order) were made inevitable was given precisely by the nationalist resolution of the problem…

Education then was meant to inculcate in women the virtues—the typically bourgeois virtues characteristic of the new social forms of "disciplining"—of orderliness, thrift, cleanliness, and a personal sense of responsibility, the practical skills of literacy, accounting, hygiene, and the ability to run the household according to the new physical and economic conditions set by the outside world. For this, she would also need to have some idea of the world outside the home, into which she could even venture as long as it did not threaten her femininity. It is this latter criterion, now invested with a characteristically nationalist content, that made possible the displacement of the boundaries of the home from the physical confines earlier defined by the rules of purdah to a more flexible, but nonetheless culturally determinate, domain set by the differences between socially approved male and female conduct. Once the essential femininity of women was fixed in terms of certain culturally visible spiritual qualities, they could go to schools, travel in public conveyances, watch public entertainment programs, and in time even take up employment outside the home. But the "spiritual" signs of her femininity were now clearly marked—in her dress, her eating habits, her social demeanor, her religiosity….

in this as in other aspects of her life, the spirituality of her character had also to be stressed in contrast with the innumerable ways men had to surrender to the pressures of the material world. The need to adjust to the new conditions outside the home had forced upon men a whole series of changes in their dress, food habits, religious observances, and social relations. Each of these capitulations now had to be compensated for by an assertion of spiritual purity on the part of women. They must not eat, drink, or smoke in the same way as men; they must continue the observance of religious rituals that men were finding difficult to carry out; they must maintain the cohesiveness of family life and solidarity with the kin to which men could not now devote much attention. The new patriarchy advocated by nationalism conferred upon women the honor of a new social responsibility, and by associating the task of female emancipation with the historical goal of sovereign nationhood, bound them to a new, and yet entirely legitimate, subordination.

As with all hegemonic forms of exercising dominance, this patriarchy combined coercive authority with the subtle force of persuasion. This was expressed most generally in the inverted ideological form of the relation of power between the sexes: the adulation of woman as goddess or as mother. Whatever its sources in the classical religions of India or in medieval religious practices, the specific ideological form in which we know the "Indian woman" construct in the modern literature and arts of India today is wholly and undeniably a product of the development of a dominant middle-class culture coeval with the era of nationalism. It served to emphasize with all the force of mythological inspiration what had in any case become a dominant characteristic of femininity in the new construct of "woman" standing as a sign for "nation," namely, the spiritual qualities of self-sacrifice, benevolence, devotion, religiosity, and so on. This spirituality did not, as we have seen, impede the chances of the woman moving out of the physical confines of the home; on the contrary, it facilitated it, making it possible for her to go into the world under conditions that would not threaten her femininity. In fact, the image of woman as goddess or mother served to erase her sexuality in the world outside the home.

-- The Nation and Its Fragments: Colonial and Postcolonial Histories, by Partha Chatterjee

CHAPTER SIX: The Nation and Its Women

THE PARADOX OF THE WOMEN'S QUESTION

The "women's question" was a central issue in the most controversial debates over social reform in early and mid-nineteenth-century Bengal— the period of its so-called renaissance. Rammohan Roy's historical fame is largely built around his campaign against the practice of the immolation of widows, Vidyasagar's around his efforts to legalize widow remarriage and abolish Kulin polygamy; the Brahmo Samaj was split twice in the 1870s over questions of marriage laws and the "age of consent." What has perplexed historians is the rather sudden disappearance of such issues from the agenda of public debate toward the close of the century. From then onward, questions regarding the position of women in society do not arouse the same degree of public passion and acrimony as they did only a few decades before. The overwhelming issues now are directly political ones—concerning the politics of nationalism.

How are we to interpret this change? Ghulam Murshid states the problem in its most obvious, straightforward form.1 If one takes seriously, that is to say, in their liberal, rationalist and egalitarian content, the mid-nineteenth-century attempts in Bengal to "modernize" the condition of women, then what follows in the period of nationalism must be regarded as a clear retrogression. Modernization began in the first half of the nineteenth century because of the penetration of Western ideas. After some limited success, there was a perceptible decline in the reform movements as popular attitudes toward them hardened. The new politics of nationalism "glorified India's past and tended to defend everything traditional"; all attempts to change customs and life-styles began to be seen as the aping of Western manners and were thereby regarded with suspicion. Consequently, nationalism fostered a distinctly conservative attitude toward social beliefs and practices. The movement toward modernization was stalled by nationalist politics.

This critique of the social implications of nationalism follows from rather simple and linear historicist assumptions. Murshid not only accepts that the early attempts at social reform were impelled by the new nationalist and progressive ideas imported from Europe, he also presumes that the necessary historical culmination of such reforms in India ought to have been, as in the West, the full articulation of liberal values in social institutions and practices. From these assumptions, a critique of nationalist ideology and practices is inevitable, the same sort of critique as that of the colonialist historians who argue that Indian nationalism was nothing but a scramble for sharing political power with the colonial rulers; its mass following only the successful activization of traditional patron-client relationships; its internal debates the squabbles of parochial factions; and its ideology a garb for xenophobia and racial exclusiveness.

Clearly, the problem of the diminished importance of the women's question in the period of nationalism deserves a different answer from the one given by Murshid. Sumit Sarkar has argued that the limitations of nationalist ideology in pushing forward a campaign for liberal and egalitarian social change cannot be seen as a retrogression from an earlier radical reformist phase.2 Those limitations were in fact present in the earlier phase as well. The renaissance reformers, he shows, were highly selective in their acceptance of liberal ideas from Europe. Fundamental elements of social conservatism such as the maintenance of caste distinctions and patriarchal forms of authority in the family, acceptance of the sanctity of the šástra (scriptures), preference for symbolic rather than substantive changes in social practices—all these were conspicuous in the reform movements of the early and mid-nineteenth century.

Following from this, we could ask: How did the reformers select what they wanted? What, in other words, was the ideological sieve through which they put the newly imported ideas from Europe? If we can reconstruct this framework of the nationalist ideology, we will be in a far better position to locate where exactly the women's question fitted in with the claims of nationalism. We will find, if I may anticipate my argument in this chapter, that nationalism did in fact provide an answer to the new social and cultural problems concerning the position of women in "modern" society, and that this answer was posited not on an identity but on a difference with the perceived forms of cultural modernity in the West. I will argue, therefore, that the relative unimportance of the women's question in the last decades of the nineteenth century is to be explained not by the fact that it had been censored out of the reform agenda or overtaken by the more pressing and emotive issues of political struggle. The reason lies in nationalism's success in situating the "women's question" in an inner domain of sovereignty, far removed from the arena of political contest with the colonial state. This inner domain of national culture was constituted in the light of the discovery of "tradition."

THE WOMEN'S QUESTION IN "TRADITION"

Apart from the characterization of the political condition of India preceding the British conquest as a state of anarchy, lawlessness, and arbitrary despotism, a central element in the ideological justification of British colonial rule was the criticism of the "degenerate and barbaric" social customs of the Indian people, sanctioned, or so it was believed, by the religious tradition. Alongside the project of instituting orderly, lawful, and rational procedures of governance, therefore, colonialism also saw itself as performing a "civilizing mission." In identifying this tradition as "degenerate and barbaric," colonialist critics invariably repeated a long list of atrocities perpetrated on Indian women, not so much by men or certain classes of men, but by an entire body of scriptural canons and ritual practices that, they said, by rationalizing such atrocities within a complete framework of religious doctrine, made them appear to perpetrators and sufferers alike as the necessary marks of right conduct. By assuming a position of sympathy with the unfree and oppressed womanhood of India, the colonial mind was able to transform this figure of the Indian woman into a sign of the inherently oppressive and unfree nature of the entire cultural tradition of a country.

Take, for example, the following account by an early nineteenth-century British traveler in India: