Ashoka

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/26/21

Highlights:

Beyond the Edicts of Ashoka, biographical information about him relies on legends written centuries later, such as the 2nd-century CE Ashokavadana ("Narrative of Ashoka", a part of the Divyavadana), and in the Sri Lankan text Mahavamsa ("Great Chronicle")….

Information about Ashoka comes from his own inscriptions; other inscriptions that mention him or are possibly from his reign; and ancient literature, especially Buddhist texts. These sources often contradict each other… while Ashoka is often attributed with building many hospitals during his time, there is no clear evidence any hospitals existed in ancient India during the 3rd century BC or that Ashoka was responsible for commissioning the construction of any….

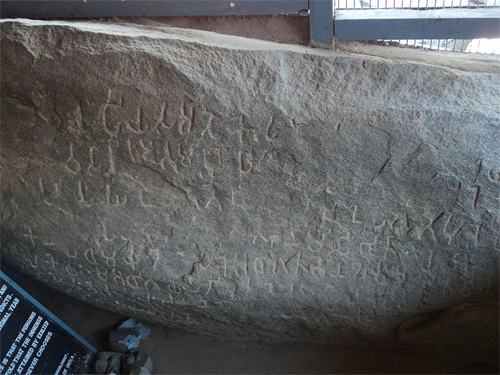

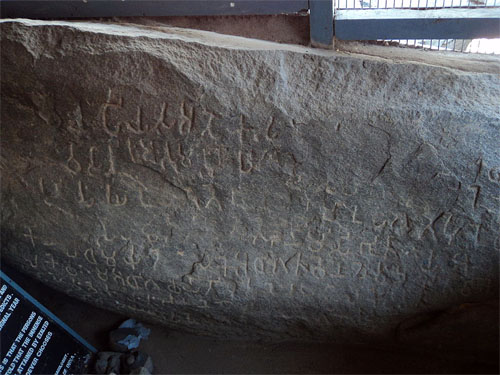

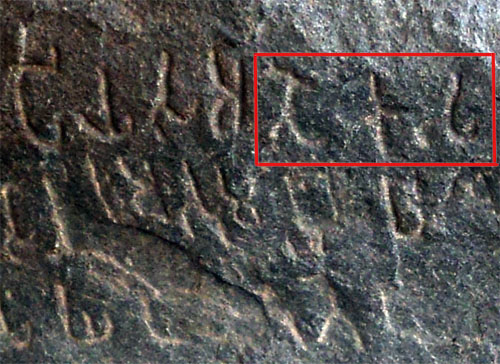

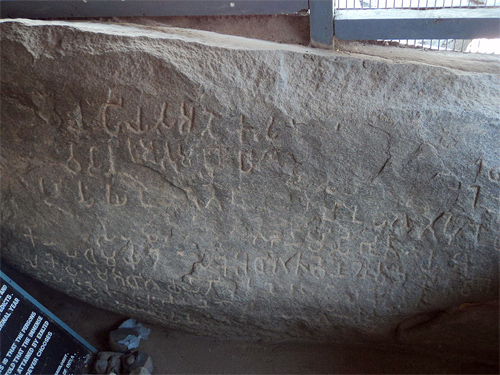

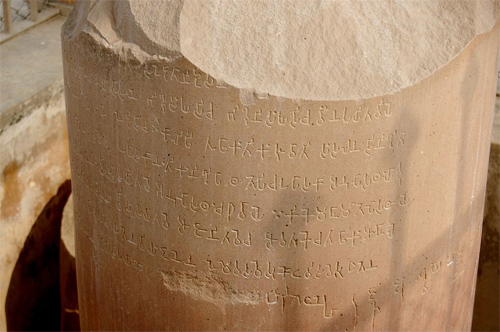

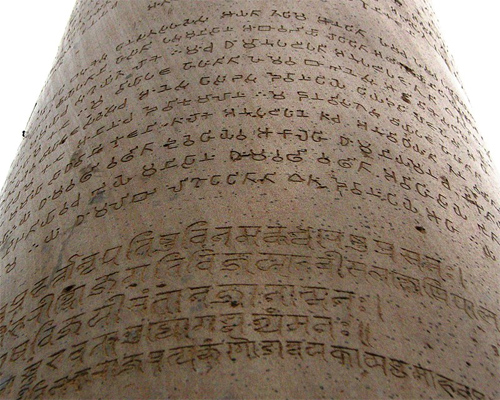

Ashoka's own inscriptions are the earliest self-representations of an imperial power in the Indian subcontinent. However, these inscriptions are focused mainly on the topic of dhamma, and provide little information regarding other aspects of the Maurya state and society. Even on the topic of dhamma, the content of these inscriptions cannot be taken at face value: in words of American academic John S. Strong, it is sometimes useful to think of Ashoka's messages as propaganda by a politician whose aim is to present a favourable image of himself and his administration, rather than record historical facts….

Much of the information about Ashoka comes from Buddhist legends, which present him as a great, ideal king. These legends appear in texts that are not contemporary to Ashoka, and were composed by Buddhist authors, who used various stories to illustrate the impact of their faith on Ashoka. This makes it necessary to exercise caution while relying on them for historical information. Among modern scholars, opinions range from downright dismissal of these legends as mythological to acceptance of all historical portions that seem plausible….

All these legends can be traced to two primary traditions:

• the North Indian tradition preserved in the Sanskrit-language texts such as Divyavadana (including its constituent Ashokavadana); and Chinese sources such as A-yü wang chuan and A-yü wang ching.

• the Sri Lankan tradition preserved in Pali-language texts, such as Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Vamsatthapakasini (a commentary on Mahavamsa), Buddhaghosha's commentary on the Vinaya, and Samanta-pasadika.

There are several major differences between the two traditions. For example, the Sri Lankan tradition emphasises Ashoka's role in convening the Third Buddhist council, and his dispatch of several missionaries to distant regions, including his son Mahinda to Sri Lanka. However, the North Indian tradition makes no mention of these events, and describes other events not found in the Sri Lankan tradition, such as a story about another son named Kunala.

Even while narrating the common stories, the two traditions diverge in several ways. For example, both Ashokavadana and Mahavamsa mention that Ashoka's queen Tishyarakshita had the Bodhi Tree destroyed. In Ashokavadana, the queen manages to have the tree healed after she realises her mistake. In the Mahavamsa, she permanently destroys the tree, but only after a branch of the tree has been transplanted in Sri Lanka. In another story, both the texts describe Ashoka's unsuccessful attempts to collect a relic of Gautama Buddha from Ramagrama. In Ashokavadana, he fails to do so because he cannot match the devotion of the Nagas who hold the relic; however, in the Mahavamsa, he fails to do so because the Buddha had destined the relic to be enshrined by king Dutthagamani of Sri Lanka. Using such stories, the Mahavamsa glorifies Sri Lanka as the new preserve of Buddhism….

Ashoka's name appears in the lists of Mauryan kings in the various Puranas, but these texts do not provide further details about him…

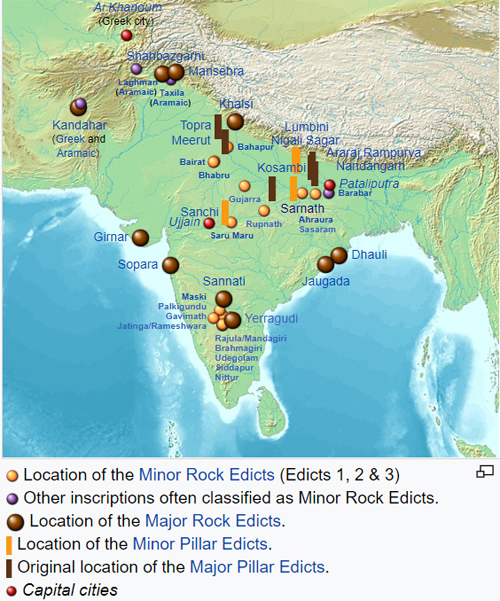

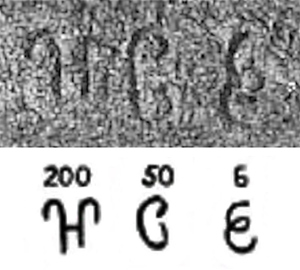

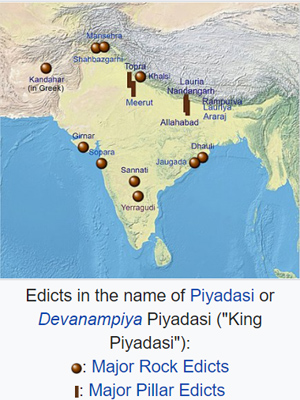

For some scholars such as Christopher I. Beckwith, Ashoka, whose name only appears in the Minor Rock Edicts, should be differentiated from the ruler Piyadasi, or Devanampiya Piyadasi (i.e. "Beloved of the Gods Piyadasi", "Beloved of the Gods" being a fairly widespread title for "King"), who is named as the author of the Major Pillar Edicts and the Major Rock Edicts. This inscriptional evidence may suggest that these were two different rulers. According to him, Piyadasi was living in the 3rd century BCE, probably the son of Chandragupta Maurya known to the Greeks as Amitrochates, and only advocating for piety ("Dharma") in his Major Pillar Edicts and Major Rock Edicts, without ever mentioning Buddhism, the Buddha or the Samgha. Also, the geographical spread of his inscription shows that Piyadasi ruled a vast Empire, contiguous with the Seleucid Empire in the West.

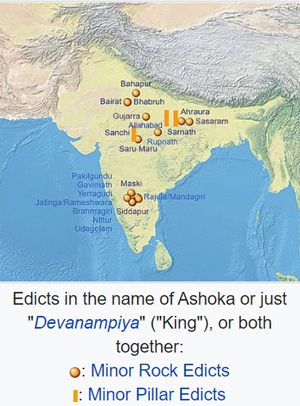

On the contrary, for Beckwith, Ashoka was a later king of the 1st–2nd century CE, whose name only appears explicitly in the Minor Rock Edicts and allusively in the Minor Pillar Edicts, and who does mention the Buddha and the Samgha, explicitly promoting Buddhism. His inscriptions cover a very different and much smaller geographical area, clustering in Central India. According to Beckwith, the inscriptions of this later Ashoka were typical of the later forms of "normative Buddhism", which are well attested from inscriptions and Gandhari manuscripts dated to the turn of the millennium, and around the time of the Kushan Empire. The quality of the inscriptions of this Ashoka is significantly lower than the quality of the inscriptions of the earlier Piyadasi….

Ashoka's own inscriptions do not describe his early life, and much of the information on this topic comes from apocryphal legends written hundreds of years after him.… these legends include obviously fictitious details such as narratives of Ashoka's past lives…

The exact date of Ashoka's birth is not certain, as the extant contemporary Indian texts did not record such details….

The Ashokavadana states that Bindusara provided Ashoka with a fourfold-army (comprising cavalry, elephants, chariots and infantry), but refused to provide any weapons for this army. Ashoka declared that weapons would appear before him if he was worthy of being a king, and then, the deities emerged from the earth, and provided weapons to the army…. the gods declared that he would go on to conquer the whole earth….

According to the Mahavamsa, Bindusara appointed Ashoka as the viceroy of present-day Ujjain… This tradition is corroborated by the Saru Maru inscription discovered in central India; this inscription states that he visited the place as a prince….

"The king, who (now after consecration) is called "Piyadasi", (once) came to this place for a pleasure tour while still a (ruling) prince, living together with his unwedded consort." – Saru Mara, by Wikipedia…

According to the Sri Lankan tradition, on his way to Ujjain, Ashoka visited Vidisha, where he fell in love with a beautiful woman. According to the Dipamvamsa and Mahamvamsa, the woman was Devi – the daughter of a merchant. According to the Mahabodhi-vamsa, she was Vidisha-Mahadevi, and belonged to the Shakya clan of Gautama Buddha. The Shakya connection may have been fabricated by the Buddhist chroniclers in an attempt to connect Ashoka's family to Buddha….

Ashoka declared that if the throne was rightfully his, the gods would crown him as the next king. At that instance, the gods did so, Bindusara died, and Ashoka's authority extended to the entire world, including the Yaksha territory located above the earth, and the Naga territory located below the earth….

The Mahavamsa… also states that Ashoka killed ninety-nine of his half-brothers, including Sumana. The Dipavamsa states that he killed a hundred of his brothers, and was crowned four years later….

The figures such as 99 and 100 are exaggerated, and seem to be a way of stating that Ashoka killed several of his brothers. Taranatha states that Ashoka, who was an illegitimate son of his predecessor, killed six legitimate princes to ascend the throne. It is possible that Ashoka was not the rightful heir to the throne, and killed a brother (or brothers) to acquire the throne. However, the story has obviously been exaggerated by the Buddhist sources, which attempt to portray him as an evil person before his conversion to Buddhism….

According to the Sri Lankan texts Mahavamsa and the Dipavamsa, Ashoka ascended the throne 218 years after the death of Gautama Buddha, and ruled for 37 years. The date of the Buddha's death is itself a matter of debate, and the North Indian tradition states that Ashoka ruled a hundred years after the Buddha's death, which has led to further debates about the date….

The Ashokavadana also calls [Ashoka] "Chandashoka", and describes several of his cruel acts:

• The ministers who had helped him ascend the throne started treating him with contempt after his ascension. To test their loyalty, Ashoka gave them the absurd order of cutting down every flower-and fruit-bearing tree. When they failed to carry out this order, Ashoka personally cut off the heads of 500 ministers.

• One day, during a stroll at a park, Ashoka and his concubines came across a beautiful Ashoka tree. The sight put him in a sensual mood, but the women did not enjoy caressing his rough skin. Sometime later, when Ashoka fell asleep, the resentful women chopped the flowers and the branches of his namesake tree. After Ashoka woke up, he burnt 500 of his concubines to death as a punishment….

The 5th century Chinese traveller Faxian states that Ashoka personally visited the underworld to study the methods of torture there, and then invented his own methods.…

Such descriptions of Ashoka as an evil person before his conversion to Buddhism appear to be a fabrication of the Buddhist authors, who attempted to present the change that Buddhism brought to him as a miracle. In an attempt to dramatise this change, such legends exaggerate Ashoka's past wickedness and his piousness after the conversion….

Ashoka's own inscriptions mention that he conquered the Kalinga region during his 8th regnal year…

On the other hand, the Sri Lankan tradition suggests that Ashoka was already a devoted Buddhist by his 8th regnal year, having converted to Buddhism during his 4th regnal year, and having constructed 84,000 viharas during his 5th–7th regnal years. The Buddhist legends make no mention of the Kalinga campaign….

According to Ashoka's Major Rock Edict 13, he conquered Kalinga 8 years after his ascension to the throne. The edict states that during his conquest of Kalinga, 100,000 men and animals were killed in action; many times that number "perished"; and 150,000 men and animals were carried away from Kalinga as captives. Ashoka states that the repentance of these sufferings caused him to devote himself to the practice and propagation of dharma. He proclaims that he now considered the slaughter, death and deportation caused during the conquest of a country painful and deplorable; and that he considered the suffering caused to the religious people and householders even more deplorable.

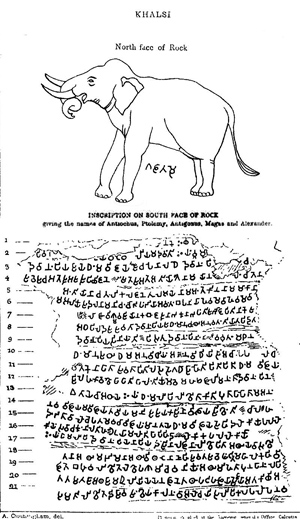

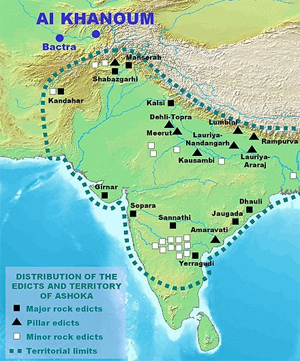

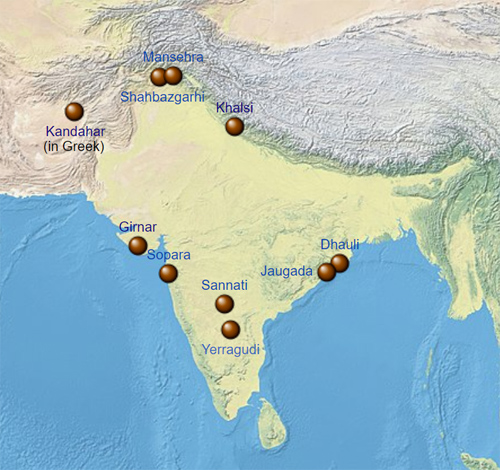

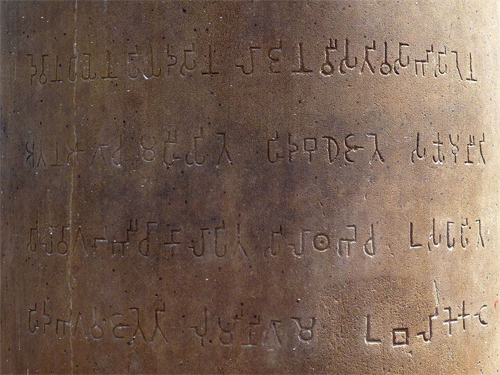

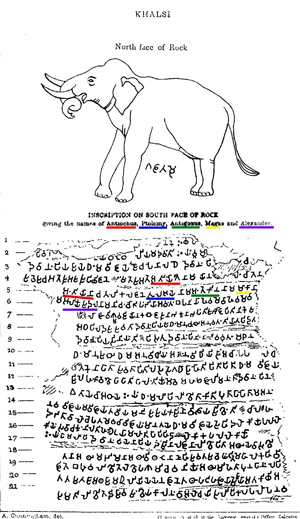

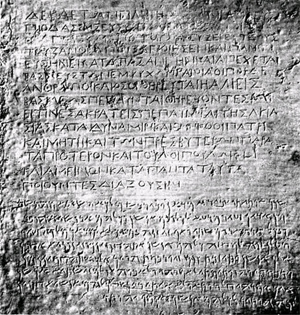

This edict has been found inscribed at several places, including Erragudi, Girnar, Kalsi, Maneshra, Shahbazgarhi and Kandahar. However, [it] is omitted in Ashoka's inscriptions found in the Kalinga region, where the Rock Edicts 13 and 14 have been replaced by two separate edicts that make no mention of Ashoka's remorse. It is possible that Ashoka did not consider it politically appropriate to make such a confession to the people of Kalinga. Another possibility is the Kalinga war and its consequences, as described in Ashoka's rock edicts, are "more imaginary than real": this description is meant to impress those far removed from the scene, and thus, unable to verify its accuracy….

Taranatha claims that Ashoka conquered the entire Jambudvipa.

Different sources give different accounts of Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism….

The Dipavamsa states that Ashoka invited several non-Buddhist religious leaders to his palace, and bestowed great gifts upon them in hope that they would be able to answer a question posed by the king. The text does not state what the question was… he met the Buddhist monk Moggaliputta Tissa, and became more devoted to the Buddhist faith. The veracity of this story is not certain. This legend about Ashoka's search for a worthy teacher may be aimed at explaining why Ashoka did not adopt Jainism, another major contemporary faith that advocates non-violence and compassion. The legend suggests that Ashoka was not attracted to Buddhism because he was looking for such a faith, rather, for a competent spiritual teacher….

The A-yu-wang-chuan states that a 7-year-old Buddhist converted Ashoka. Another story claims that the young boy ate 500 Brahmanas who were harassing Ashoka for being interested in Buddhism; these Brahmanas later miraculously turned into Buddhist bhikkus at the Kukkutarama monastery, where Ashoka paid a visit….

Both Mahavamsa and Ashokavadana state that Ashoka constructed 84,000 stupas or viharas….

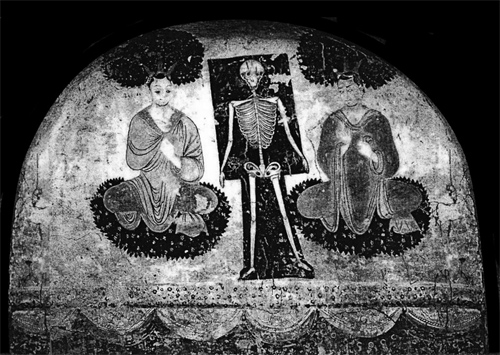

The Ashokavadana states that Ashoka collected seven out of the eight relics of Gautama Buddha, and had their portions kept in 84,000 boxes made of gold, silver, cat's eye, and crystal. He ordered the construction of 84,000 stupas throughout the earth, in towns that had a population of 100,000 or more. He told Elder Yashas, a monk at the Kukkutarama monastery, that he wanted these stupas to be completed on the same day. Yashas stated that he would signal the completion time by eclipsing the sun with his hand. When he did so, the 84,000 stupas were completed at once.

The Mahavamsa states that Ashoka ordered construction of 84,000 viharas (monasteries) rather than the stupas to house the relics. Like Ashokavadana, the Mahavamsa describes Ashoka's collection of the relics, but does not mention this episode in the context of the construction activities. It states that Ashoka decided to construct the 84,000 viharas when Moggaliputta Tissa told him that there were 84,000 sections of the Buddha's Dhamma. Ashoka himself began the construction of the Ashokarama vihara, and ordered subordinate kings to build the other viharas. Ashokarama was completed by the miraculous power of Thera Indagutta, and the news about the completion of the 84,000 viharas arrived from various cities on the same day.

The number 84,000 is an obvious exaggeration, and it appears that in the later period, the construction of almost every old stupa was attributed to Ashoka….

Ashoka's rock edicts suggest that during his 8th–9th regnal years, he made a pilgrimage to the Bodhi Tree, started propagating dhamma, and performed social welfare activities. The welfare activities included establishment of medical treatment facilities for humans and animals…

The Sri Lankan tradition presents a greater role for Ashoka in the Buddhist community. In this tradition, Ashoka starts feeding monks on a large scale. His lavish patronage to the state patronage leads to many fake monks joining the sangha. The true Buddhist monks refuse to co-operate with these fake monks, and therefore, no uposatha ceremony is held for seven years. The king attempts to eradicate the fake monks, but during this attempt, an over-zealous minister ends up killing some real monks. The king then invites the elder monk Moggaliputta-Tissa, to help him expel non-Buddhists from the monastery founded by him at Pataliputra. 60,000 monks (bhikkhus) convicted of being heretical are de-frocked in the ensuing process. The uposatha ceremony is then held, and Tissa subsequently organises the Third Buddhist council, during the 17th regnal year of Ashoka. Tissa compiles Kathavatthu, a text that reaffirms Theravadin orthodoxy on several points.

The North Indian tradition makes no mention of these events, which has led to doubts about the historicity of the Third Buddhist council….

in his Minor Rock Edict 3, Ashoka recommends the members of the Sangha to study certain texts (most of which remain unidentified)….

In the Sri Lankan tradition, Moggaliputta-Tissa –- who is patronised by Ashoka –- sends out nine Buddhist missions to spread Buddhism in the "border areas" in c. 250 BCE.…

The tradition adds that during his 19th regnal year, Ashoka's daughter Sanghamitta went to Sri Lanka to establish an order of nuns, taking a sapling of the sacred Bodhi Tree with her.

The North Indian tradition makes no mention of these events. Ashoka's own inscriptions also appear to omit any mention of these events…

The Rock Edict XIII states that Ashoka won a "dhamma victory" by sending messengers to five kings and several other kingdoms. Whether these missions correspond to the Buddhist missions recorded in the Buddhist chronicles is debated. Indologist Etienne Lamotte argues that the "dhamma" missionaries mentioned in Ashoka's inscriptions were probably not Buddhist monks, as this "dhamma" was not same as "Buddhism". Moreover, the lists of destinations of the missions and the dates of the missions mentioned in the inscriptions do not tally [with] the ones mentioned in the Buddhist legends….

According to Gombrich, the mission may have included representatives of other religions, and thus, Lamotte's objection about "dhamma" is not valid. The Buddhist chroniclers may have decided not to mention these non-Buddhists, so as not to sideline Buddhism. Frauwallner and Gombrich also believe that Ashoka was directly responsible for the missions, since only a resourceful ruler could have sponsored such activities. The Sri Lankan chronicles, which belong to the Theravada school, exaggerate the role of the Theravadin monk Moggaliputta-Tissa in order to glorify their sect….

According to the Ashokavadana, Ashoka resorted to violence even after converting to Buddhism. For example:

• He slowly tortured Chandagirika to death in the "hell" prison.

• He ordered a massacre of 18,000 heretics for a misdeed of one.

• He launched a pogrom against the Jains, announcing a bounty on the head of any heretic; this results in the beheading of his own brother -– Vitashoka.

According to the Ashokavadana, a non-Buddhist in Pundravardhana drew a picture showing the Buddha bowing at the feet of the Nirgrantha leader Jnatiputra. The term nirgrantha ("free from bonds") was originally used for a pre-Jaina ascetic order, but later came to be used for Jaina monks. "Jnatiputra" is identified with Mahavira, 24th Tirthankara of Jainism. The legend states that on complaint from a Buddhist devotee, Ashoka issued an order to arrest the non-Buddhist artist, and subsequently, another order to kill all the Ajivikas in Pundravardhana. Around 18,000 followers of the Ajivika sect were executed as a result of this order. Sometime later, another Nirgrantha follower in Pataliputra drew a similar picture. Ashoka burnt him and his entire family alive in their house…

[T]hese stories of persecutions of rival sects by Ashoka appear to be clear fabrications arising out of sectarian propaganda….

Ashoka's last dated inscription -- the Pillar Edict 4 is from his 26th regnal year. The only source of information about Ashoka's later years are the Buddhist legends….

Both Mahavamsa and Ashokavadana state that Ashoka extended favours and attention to the Bodhi Tree, and a jealous Tissarakkha mistook "Bodhi" to be a mistress of Ashoka. She then used black magic to make the tree wither. According to the Ashokavadana, she hired a sorceress to do the job, and when Ashoka explained that "Bodhi" was the name of a tree, she had the sorceress heal the tree. According to the Mahavamsa, she completely destroyed the tree, during Ashoka's 34th regnal year.

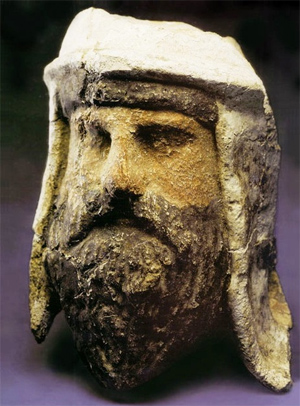

The Ashokavadana states that Tissarakkha (called "Tishyarakshita" here) made sexual advances towards Ashoka's son Kunala, but Kunala rejected her. Subsequently, Ashoka granted Tissarakkha kingship for seven days, and during this period, she tortured and blinded Kunala. Ashoka then threatened to "tear out her eyes, rip open her body with sharp rakes, impale her alive on a spit, cut off her nose with a saw, cut out her tongue with a razor." Kunala regained his eyesight miraculously, and pleaded for mercy on the queen, but Ashoka had her executed anyway. Kshemendra's Avadana-kalpa-lata also narrates this legend, but seeks to improve Ashoka's image by stating that he forgave the queen after Kunala regained his eyesight….

According to the Ashokavadana, the emperor fell severely ill during his last days. He started using state funds to make donations to the Buddhist sangha, prompting his ministers to deny him access to the state treasury. Ashoka then started donating his personal possessions, but was similarly restricted from doing so. On his deathbed, his only possession was the half of a myrobalan fruit, which he offered to the sangha as his final donation….

Various sources mention five consorts of Ashoka: Devi (or Vedisa-Mahadevi-Shakyakumari), Karuvaki, Asandhimitra (Pali: Asandhimitta), Padmavati, and Tishyarakshita (Pali: Tissarakkha).

Kaurvaki is the only queen of Ashoka known from his own inscriptions: she is mentioned in an edict inscribed on a pillar at Allahabad. The inscription names her as the mother of prince Tivara, and orders the royal officers (mahamattas) to record her religious and charitable donations….

According to the Mahavamsa, Ashoka's chief queen was Asandhimitta, who died four years before him. It states that she was born as Ashoka's queen because in a previous life, she directed a pratyekabuddha to a honey merchant (who was later reborn as Ashoka). Some later texts also state that she additionally gave the pratyekabuddha a piece of cloth made by her. These texts include the Dasavatthuppakarana, the so-called Cambodian or Extended Mahavamsa (possibly from 9th–10th centuries), and the Trai Bhumi Katha (15th century). These texts narrate another story: one day, Ashoka mocked Asandhamitta [as she] was enjoying a tasty piece of sugarcane without having earned it through her karma. Asandhamitta replied that all her enjoyments resulted from merit resulting from her own karma. Ashoka then challenged her to prove this by procuring 60,000 robes as an offering for monks. At night, the guardian gods informed her about her past gift to the pratyekabuddha, and next day, she was able to miraculously procure the 60,000 robes. An impressed Ashoka makes her his favourite queen, and even offers to make her a sovereign ruler. Asandhamitta refuses the offer, but still invokes the jealousy of Ashoka's 16,000 other wives. Ashoka proves her superiority by having 16,000 identical cakes baked with his royal seal hidden in only one of them. Each wife is asked to choose a cake, and only Asandhamitta gets the one with the royal seal. The Trai Bhumi Katha claims that it was Asandhamitta who encouraged her husband to become a Buddhist, and to construct 84,000 stupas and 84,000 viharas.

According to Mahavamsa, after Asandhamitta's death, Tissarakkha became the chief queen. The Ashokavadana does not mention Asandhamitta at all, but does mention Tissarakkha as Tishyarakshita. The Divyavadana mentions another queen called Padmavati, who was the mother of the crown-prince Kunala.

As mentioned above, according to the Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka fell in love with Devi (or Vidisha-Mahadevi), as a prince in central India. After Ashoka's ascension to the throne, Devi chose to remain at Vidisha than move to the royal capital Pataliputra. According to the Mahavamsa, Ashoka's chief queen was Asandhamitta, not Devi: the text does not talk of any connection between the two women, so it is unlikely that Asandhamitta was another name for Devi….

Tivara, the son of Ashoka and Karuvaki, is the only of Ashoka's sons to be mentioned by name in the inscriptions.

According to North Indian tradition, Ashoka had a son named Kunala. Kunala had a son named Samprati.

The Sri Lankan tradition mentions a son called Mahinda, who was sent to Sri Lanka as a Buddhist missionary; this son is not mentioned at all in the North Indian tradition. The Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang states that Mahinda was Ashoka's younger brother (Vitashoka or Vigatashoka) rather than his illegitimate son.

The Divyavadana mentions the crown-prince Kunala alias Dharmavivardhana, who was a son of queen Padmavati. According to Faxian, Dharmavivardhana was appointed as the governor of Gandhara.

The Rajatarangini mentions Jalauka as a son of Ashoka.

According to Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka had a daughter named Sanghamitta, who became a Buddhist nun. A section of historians, such as Romila Thapar, doubt the historicity of Sanghamitta, based on the following points:

• The name "Sanghamitta", which literally means the friend of the Buddhist Order (sangha), is unusual, and the story of her going to Ceylon so that the Ceylonese queen could be ordained appears to be an exaggeration.

• The Mahavamsa states that she married Ashoka's nephew Agnibrahma, and the couple had a son named Sumana. The contemporary laws regarding exogamy would have forbidden such a marriage between first cousins.

• According to the Mahavamsa, she was 18 years old when she was ordained as a nun. The narrative suggests that she was married two years earlier, and that her husband as well as her child were ordained. It is unlikely that she would have been allowed to become a nun with such a young child.

Another source mentions that Ashoka had a daughter named Charumati, who married a kshatriya named Devapala.

According to the Ashokavadana, Ashoka had an elder half-brother named Susima. According to the Sri Lankan tradition, Ashoka killed his 99 half-brothers.

Various sources mention that one of Ashoka's brothers survived his ascension, and narrate stories about his role in the Buddhist community.

• According to Sri Lankan tradition, this brother was Tissa, who initially lived a luxurious life, without worrying about the world. To teach him a lesson, Ashoka put him on the throne for a few days, then accused him of being an usurper, and sentenced him to die after seven days. During these seven days, Tissa realised that the Buddhist monks gave up pleasure because they were aware of the eventual death. He then left the palace, and became an arhat.

• The Theragatha commentary calls this brother Vitashoka. According to this legend, one day, Vitashoka saw a grey hair on his head, and realised that he had become old. He then retired to a monastery, and became an arhat.

• Faxian calls the younger brother Mahendra, and states that Ashoka shamed him for his immoral behaviour. The brother than retired to a dark cave, where he meditated, and became an arhat. Ashoka invited him to return to the family, but he preferred to live alone on a hill. So, Ashoka had a hill built for him within Pataliputra.

• The Ashoka-vadana states that Ashoka's brother was mistaken for a Nirgrantha, and killed during a massacre of the Nirgranthas ordered by Ashoka.

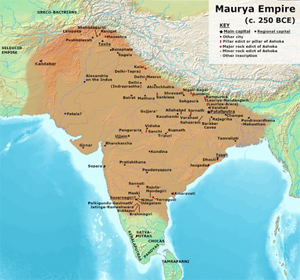

Ashoka's empire stretched from Afghanistan to Bengal to southern India. Several modern maps depict it as covering nearly all of the Indian subcontinent, except the southern tip.

Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund believe that Ashoka's empire did not include large parts of India, which were controlled by autonomous tribes….

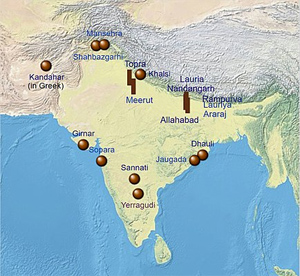

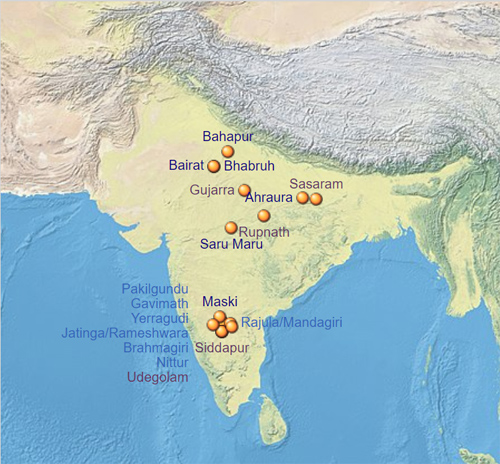

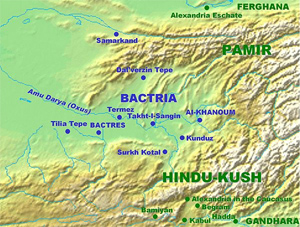

The distribution of Ashoka's inscriptions suggests that his empire included almost the entire Indian subcontinent, except its southernmost parts…. In the north-west, Ashoka's kingdom extended up to Kandahar, to the east of the Seleucid Empire ruled by Antiochus II. The capital of Ashoka's empire was Pataliputra in the Magadha region….

A legend in the Buddhist text Vamsatthapakasini states that an Ajivika ascetic invited to interpret a dream of Ashoka's mother had predicted that he would patronise Buddhism and destroy 96 heretical sects. However, such assertions are directly contradicted by Ashoka's own inscriptions. Ashoka's edicts, such as the Rock Edicts 6, 7, and 12, emphasise tolerance of all sects. Similarly, in his Rock Edict 12, Ashoka honours people of all faiths. In his inscriptions, Ashoka dedicates caves to non-Buddhist ascetics, and repeatedly states that both Brahmins and shramanas deserved respect. He also tells people "not to denigrate other sects, but to inform themselves about them".

In fact, there is no evidence that Buddhism was a state religion under Ashoka. None of Ashoka's extant edicts record his direct donations to the Buddhists….

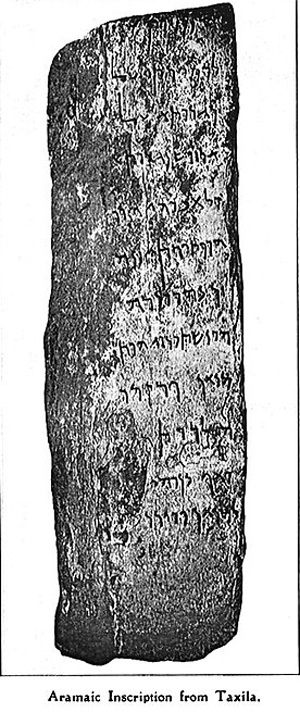

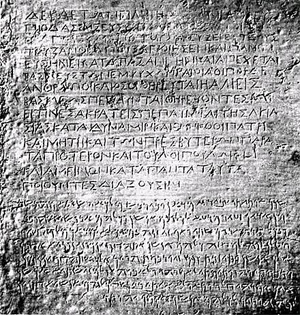

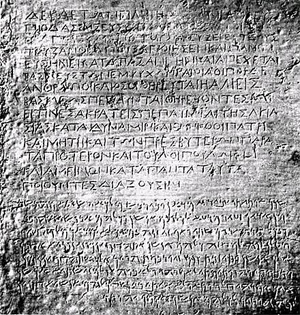

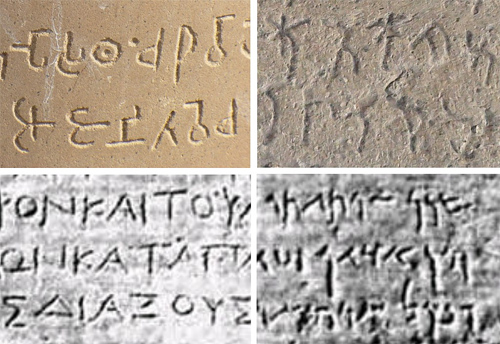

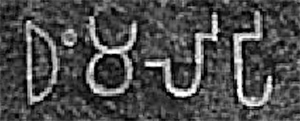

Ashoka's various inscriptions suggest that he devoted himself to the propagation of "Dharma" (Pali: Dhamma), a term that refers to the teachings of Gautama Buddha in the Buddhist circles. However, Ashoka's own inscriptions do not mention Buddhist doctrines such as the Four Noble Truths or Nirvana. The word "Dharma" has various connotations in the Indian religions, and can be generally translated as "law, duty, or righteousness". In the Kandahar inscriptions of Ashoka, the word "Dharma" has been translated as eusebeia (Greek) and qsyt (Aramaic), which further suggests that his "Dharma" meant something more generic than Buddhism....

Ashoka instituted a new category of officers called the dhamma-mahamattas, who were tasked with the welfare of the aged, the infirm, the women and children, and various religious sects. They were also sent on diplomatic missions to the Hellenistic kingdoms of west Asia, in order to propagate the dhamma.

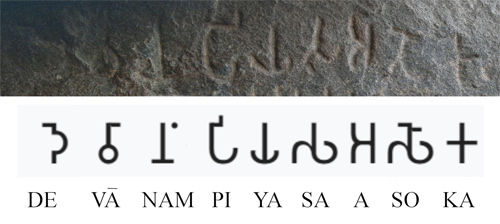

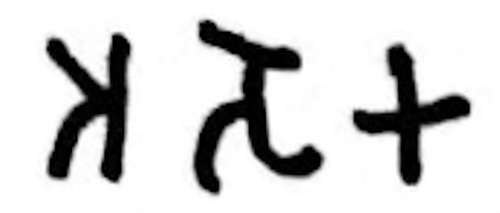

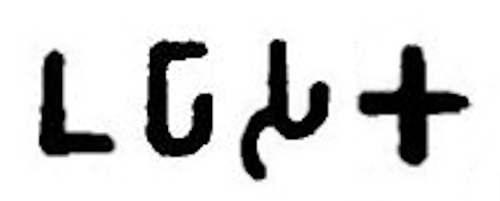

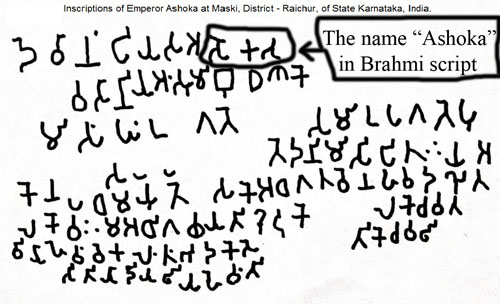

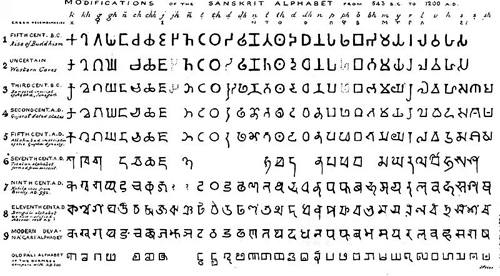

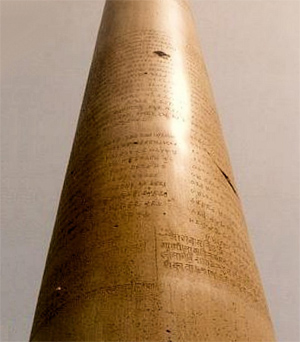

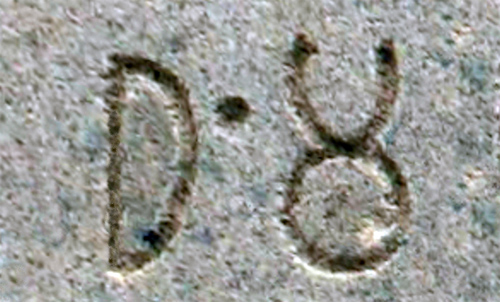

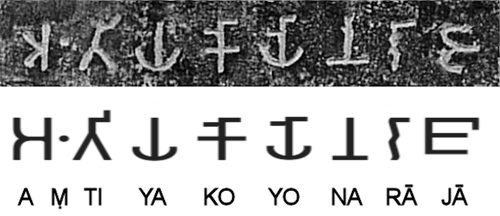

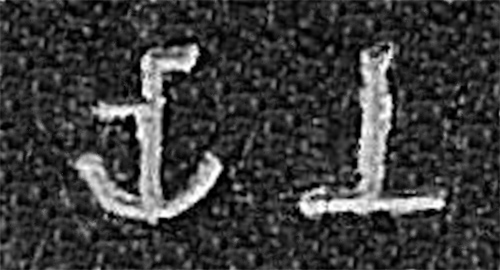

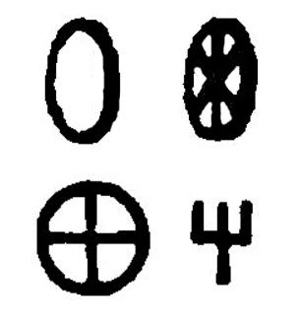

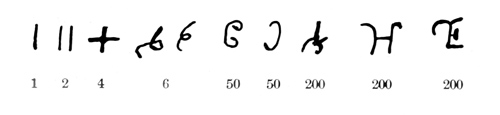

Historically, the image of Ashoka in the global Buddhist circles was based on legends (such as those mentioned in the Ashokavadana) rather than his rock edicts. This was because the Brahmi script in which these edicts were written was forgotten soon and remained undeciphered until its study by James Prinsep in the 19th century. The writings of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrims such as Faxian and Xuanzang suggest that Ashoka's inscriptions mark the important sites associated with Gautama Buddha. These writers attribute Buddhism-related content to Ashoka's edicts, but this content does not match with the actual text of the inscriptions as determined by modern scholars after the decipherment of the Brahmi script. It is likely that the script was forgotten by the time of Faxian, who probably relied on local guides; these guides may have made up some Buddhism-related interpretations to gratify him, or may have themselves relied on faulty translations based on oral traditions. Xuanzang may have encountered a similar situation, or may have taken the supposed content of the inscriptions from Faxian's writings. This theory is corroborated by the fact that some Brahmin scholars are known to have similarly come up with a fanciful interpretation of Ashoka pillar inscriptions, when requested to decipher them by the 14th century Muslim king Firuz Shah Tughlaq. According to Shams-i Siraj's Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi, after the king had these pillars transported from Topra and Mirat to Delhi as war trophies, these Brahmins told him that the inscriptions prophesized that nobody would be able to remove the pillars except a king named Firuz. Moreover, by this time, there were local traditions that attributed the erection of these pillars to the legendary hero Bhima….

Because he banned hunting, created many veterinary clinics and eliminated meat eating on many holidays, the Mauryan Empire under Ashoka has been described as "one of the very few instances in world history of a government treating its animals as citizens who are as deserving of its protection as the human residents"….

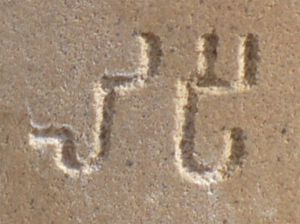

There is obvious and undeniable trace of cultural contact through the adoption of the Kharosthi script, and, as Achaemenid influence is seen in some of the formulations used by Ashoka in his inscriptions. This indicates to us that Ashoka was indeed in contact with other cultures, and was an active part in mingling and spreading new cultural ideas beyond his own immediate walls….

It is possible, but not certain, that Ashoka received letters from Greek rulers and was acquainted with the Hellenistic royal orders in the same way as he perhaps knew of the inscriptions of the Achaemenid kings, given the presence of ambassadors of Hellenistic kings in India…

The Greeks in India even seem to have played an active role in the propagation of Buddhism, as some of the emissaries of Ashoka, such as Dharmaraksita, are described in Pali sources as leading Greek (Yona) Buddhist monks, active in spreading Buddhism (the Mahavamsa, XII).

Some Greeks (Yavana) may have played an administrative role in the territories ruled by Ashoka. The Girnar inscription of Rudradaman records that during the rule of Ashoka, a Yavana Governor was in charge in the area of Girnar, Gujarat, mentioning his role in the construction of a water reservoir.

It is thought that Ashoka's palace at Patna was modelled after the Achaemenid palace of Persepolis….

Buddhist legends mention stories about Ashoka's past lives. According to a Mahavamsa story, Ashoka, Nigrodha and Devnampiya Tissa were brothers in a previous life. In that life, a pratyekabuddha was looking for honey to cure another, sick pratyekabuddha. A woman directed him to a honey shop owned by the three brothers. Ashoka generously donated honey to the pratyekabuddha, and wished to become the sovereign ruler of Jambudvipa for this act of merit. The woman wished to become his queen, and was reborn as Ashoka's wife Asandhamitta….

According to an Ashokavadana story, Ashoka was born as Jaya… he gave the Gautama Buddha dirt imagining it to be food. The Buddha approved of the donation, and Jaya declared that he would become a king by this act of merit. The text also states that Jaya's companion Vijaya was reborn as Ashoka's prime-minister Radhagupta…. The Chinese writer Pao Ch'eng's Shih chia ju lai ying hua lu asserts that an insignificant act like gifting dirt could not have been meritorious enough to cause Ashoka's future greatness. Instead, the text claims that in another past life, Ashoka commissioned a large number of Buddha statues as a king, and this act of merit caused him to become a great emperor in the next life.

The 14th century Pali-language fairy tale Dasavatthuppakarana (possibly from c. 14th century) combines the stories about the merchant's gift of honey, and the boy's gift of dirt. It narrates a slightly different version of the Mahavamsa story, stating that it took place before the birth of the Gautama Buddha. It then states that the merchant was reborn as the boy who gifted dirt to the Buddha; however, in this case, the Buddha [gave it to] his attendant Ānanda to create plaster from the dirt, which is used [to] repair cracks in the monastery walls….

Ashoka is often credited with the beginning of stone architecture in India, possibly following the introduction of stone-building techniques by the Greeks after Alexander the Great….

Ashoka probably got the idea of putting up these inscriptions from the neighbouring Achaemenid empire….

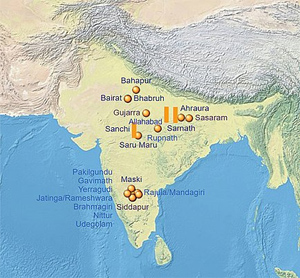

Ashoka's inscriptions have not been found at major cities of the Maurya empire, such as Pataliputra, Vidisha, Ujjayini, and Taxila…. the 7th century Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang refers to some of Ashoka's pillar edicts, which have not been discovered by modern researchers….

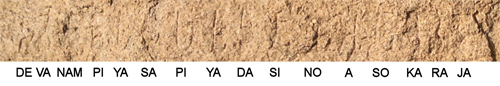

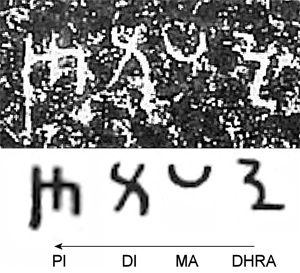

Ashoka had almost been forgotten, but in the 19th century James Prinsep contributed in the revelation of historical sources. After deciphering the Brahmi script, Prinsep had originally identified the "Priyadasi" of the inscriptions he found with the King of Ceylon Devanampiya Tissa. However, in 1837, George Turnour discovered an important Sri Lankan manuscript (Dipavamsa, or "Island Chronicle") associating Piyadasi with Ashoka:

"Two hundred and eighteen years after the beatitude of the Buddha, was the inauguration of Piyadassi, .... who, the grandson of Chandragupta, and the son of Bindusara, was at the time Governor of Ujjayani."— Dipavamsa.

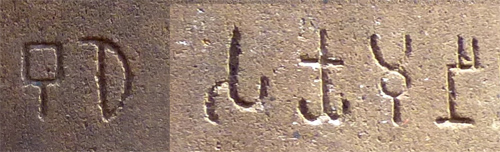

Since then, the association of "Devanampriya Priyadarsin" with Ashoka was confirmed through various inscriptions, and especially confirmed in the Minor Rock Edict inscription discovered in Maski, directly associating Ashoka with his regnal title Devanampriya ("Beloved-of-the-Gods")…

The use of Buddhist sources in reconstructing the life of Ashoka has had a strong influence on perceptions of Ashoka, as well as the interpretations of his Edicts…. The only source of information not attributable to Buddhist sources are the Ashokan Edicts, and these do not explicitly state that Ashoka was a Buddhist. In his edicts, Ashoka expresses support for all the major religions of his time: Buddhism, Brahmanism, Jainism, and Ajivikaism, and his edicts addressed to the population at large (there are some addressed specifically to Buddhists; this is not the case for the other religions) [which] generally focus on moral themes [that] members of all the religions would accept….

[T]he edicts alone strongly indicate that he was a Buddhist… He also used the word "dhamma" to refer to qualities of the heart that underlie moral action; this was an exclusively Buddhist use of the word….

After Ashoka's death, the Maurya empire declined rapidly. The various Puranas provide different details about Ashoka's successors, but all agree that they had relatively short reigns. The empire seems to have weakened, fragmented, and suffered an invasion from the Bactrian Greeks….

Romila Thapar, have suggested that the extent and impact of his pacifism have been "grossly exaggerated"….

-- Ashoka, by Wikipedia

Ashoka: Great-grandson of Shakuni and son of Shachinara's first cousin. Built a great city called Srinagara (near but not same as the modern-day Srinagar). In his days, the mlechchhas (foreigners) overran the country, and he took sannyasa. According to Kalhana's account, this Ashoka would have ruled in the 2nd millennium BCE, and was a member of the dynasty founded by Godhara. Kalhana also states that this king had adopted the doctrine of Jina, constructed stupas and Shiva temples, and appeased Bhutesha (Shiva) to obtain his son Jalauka. Despite the discrepancies, multiple scholars identify Kalhana's Ashoka with the Mauryan emperor Ashoka, who adopted Buddhism.[Guruge 1994, pp. 185–186. Guruge, Ananda (1994). "King Aśoka and Buddhism: historical and literary studies". In Nuradha Seneviratna (ed.). King Asoka and Buddhism: Historical and Literary Studies. Buddhist Publication Society. ISBN 978-955-24-0065-0.] Although "Jina" is a term generally associated with Jainism, some ancient sources use it to refer to the Buddha.[Lahiri 2015, pp. 378–380. Lahiri, Nayanjot (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-91525-1.]

-- Rajatarangini, by Wikipedia

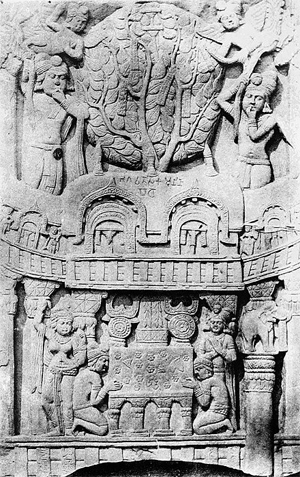

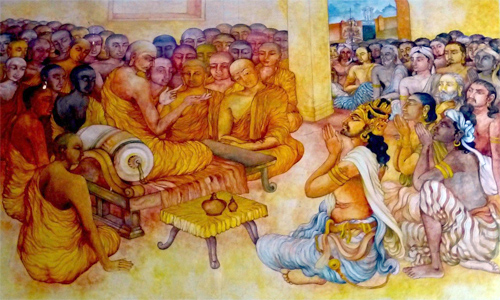

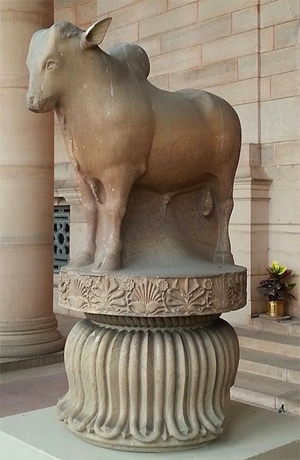

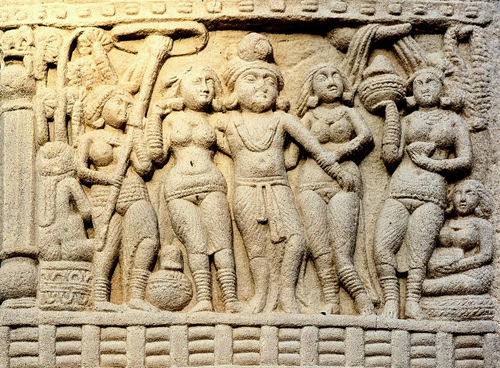

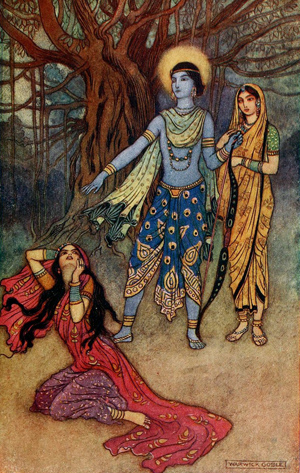

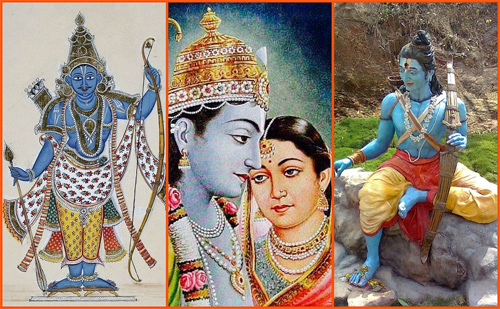

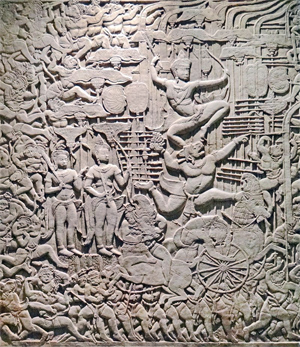

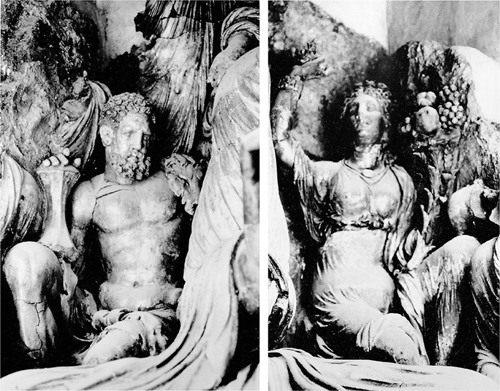

A c. 1st century BCE/CE relief from Sanchi, showing Ashoka on his chariot, visiting the Nagas at Ramagrama.[1][2]

3rd Mauryan Emperor

Reign: c. 268 – c. 232 BCE[3]

Coronation: 268 BCE[3]

Founder: Chandragupta Maurya

Predecessor: Bindusara

Successor: Dasharatha

Born: c. 304 BCE, Pataliputra, Mauryan Empire (adjacent to present-day Patna, Bihar, India)

Died: 232 BCE (aged c. 71 – 72), Pataliputra, modern-day Patna, Bihar, India

Spouses: Devi (Sri Lankan tradition); Karuvaki (own inscriptions); Padmavati (North Indian tradition); Asandhimitra (Sri Lankan tradition); Tishyaraksha (Sri Lankan and North Indian tradition)

Issue: Mahendra (Sri Lankan tradition); Sanghamitra (Sri Lankan tradition); Tivala (own inscriptions); Kunala (North Indian tradition); Charumati

Dynasty: Maurya

Father: Bindusara

Mother: Subhadrangi or Dharma[note 1]

Mother of Ashoka

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 5/26/21

Mother of Ashoka

Empress consort of the Maurya Empire

Spouse: Bindusara

Issue: Ashoka; Vitashoka (according to Ashokavadana) / Tissa (according to Mahavamsa)

Dynasty: Maurya

Father: A Brahmin of Champa (according to Ashokavadana)

Religion: Ajivika (according to Mahavamsa-tika)

The information about mother of Ashoka (c. 3rd century BCE), the Maurya emperor of ancient India, varies between different sources.

Name

The various Buddhist texts provide different names for Ashoka's mother:

• Subhadrangi, in Asokavadanamala[1][2]

• Dharma (Pali: Dhamma), in Vamsatthapakasini or Mahavamsa-tika, a 10th century commentary on Mahavamsa[2]

• Janapada-kalyani, in a Divyavadana legend;[3] according to scholar Ananda W. P. Guruge, this is not a name, but an epithet.[1]

Ancestry

Ashokavadana, which does not mention Ashoka's mother by name,[4] states that she was the daughter of a Brahmin from Champa.[5] According to the Mahavamsa-tika, she belonged to the Moriya Kshatriya clan.[2]

According to the 2nd century historian Appian, Ashoka's grandfather Chandragupta entered into a marital alliance with the Greek ruler Seleucus I Nicator, which has led to speculation that Ashoka's father Bindusara (or Chandragupta himself) married a Greek princess. However, there is no evidence that Ashoka's mother (or grandmother) was Greek, and the idea has been dismissed by most historians.[6]

Ashokavadana legend

The Ashokavadana legend about Ashoka's mother goes like this: She was the daughter of a Brahmin from the Champa city near the Mauryan capital Pataliputra. She was extremely beautiful, and some unnamed fortune-tellers predicted that she would marry a king. They also prophesized that she would bear two sons, one of whom will become a chakravartin (universal) king, while the other would be religiously-inclined. Accordingly, her father took her to Pataliputra, and offered him in marriage to king Bindusara.[7][8]

Bindusara considered the woman an auspicious celestial maiden, and inducted her into his harem. The king's concubines, who were jealous of her beauty, did not let her sleep with the king, and instead trained her as a barber. She soon became an expert barber, and whenever she groomed the king's hair and beard, the king would become relaxed and fall asleep. Pleased with her, the king promised to grant her one wish, to which she asked the king to have intercourse with her. The king stated that he was a Kshatriya (member of the warrior class), and would not sleep with a low-class barber girl. The girl explained that she was the daughter of a Brahmin (a member of the high priestly class), and had been made a barber by the other women in the harem. The king then told her not to work as a barber, and made her his chief queen.[9]

After some time, she gave birth to a boy. She named the child Ashoka, because she had become "without sorrow" (a-shoka) when he was born. Later, she gave birth to a second son. She named the child Vitashoka, because her sorrow had ceased (vigate-shoke) when he was born.[9]

Mahavamsa-tika legend

According to the Mahavamsa-tika, Ashoka's mother - named Dhamma - was a devotee of the Ajivika sect. During her pregnancy, she once said that she wanted to "trample on the moon and the sun to play with the stars and to eat up the forests". Based on an interpretation of this wish, an Ajivika ascetic predicted that her son would conquer and rule over entire India, destroy 96 heretical sects, and promote Buddhism. The ascetic also predicted that the son would kill his brothers for displeasing him (the text later states that Ashoka killed 99 out of his 100 brothers).[10]

References

1. Ananda W. P. Guruge 1993, p. 19.

2. Radhakumud Mookerji 1962, p. 2.

3. Upinder Singh 2008, p. 332.

4. Nayanjot Lahiri 2015, p. 323:"In the Ashokavadana, Ashoka's mother is not named."

5. John S. Strong 1989, pp. 204-205.

6. Romila Thapar 1961, p. 20.

7. John S. Strong 1989, p. 204.

8. Nayanjot Lahiri 2015, pp. 31-32.

9. John S. Strong 1989, p. 205.

10. Romila Thapar 1961, p. 26.

11. Playing onscreen mother was a challenge: Pallavi Subhash, IBN Live, 31 January 2015, archived from the original on 2 February 2015

Bibliography

• Ananda W. P. Guruge (1993). Aśoka, the Righteous: A Definitive Biography. Central Cultural Fund. ISBN 978-955-9226-00-0.

• John S. Strong (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

• Nayanjot Lahiri (5 August 2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-05777-7.

• Radhakumud Mookerji (1962). Aśoka (3rd revised ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0582-8.

• Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.