by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/4/21

Not to be confused with his father and Buddhist scholar Dharmananda Damodar Kosambi.

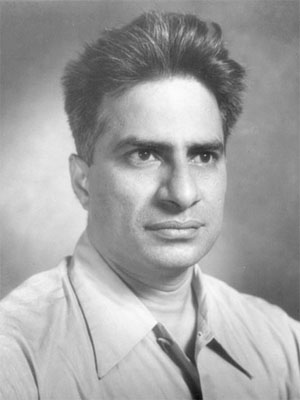

D. D. Kosambi

Born: 31 July 1907, Kosben, Goa, India

Died: 29 June 1966 (aged 58), Pune, India

Occupation: Mathematician and Marxist historian

Relative:s Dharmanand Kosambi (father); Meera Kosambi (daughter)

Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi (31 July 1907 – 29 June 1966) was an Indian polymath with interests in mathematics, statistics, philology, history, and genetics. He contributed to genetics by introducing the Kosambi map function.[1] In statistics, he was the first person to develop orthogonal infinite series expressions for stochastic processes via the Kosambi–Karhunen–Loève theorem.[2][3] He is also well known for his work in numismatics and for compiling critical editions of ancient Sanskrit texts. His father, Dharmananda Damodar Kosambi, had studied ancient Indian texts with a particular emphasis on Buddhism and its literature in the Pali language. Damodar Kosambi emulated him by developing a keen interest in his country's ancient history. He was also a Marxist historian specialising in ancient India who employed the historical materialist approach in his work.[4] He is particularly known for his classic work An Introduction to the Study of Indian History.

He is described as "the patriarch of the Marxist school of Indian historiography".[4] Kosambi was critical of the policies of then prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, which, according to him, promoted capitalism in the guise of democratic socialism. He was an enthusiast of the Chinese revolution and its ideals, and, in addition, a leading activist in the World Peace Movement.

Early life

Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi was born at Kosben in Portuguese Goa to the Buddhist scholar Dharmananda Damodar Kosambi. After a few years of schooling in India, in 1918, Damodar and his elder sister, Manik travelled to Cambridge, Massachusetts with their father, who had taken up a teaching position at the Cambridge Latin School.[5] Their father was tasked by Professor Charles Rockwell Lanman of Harvard University to complete compiling a critical edition of Visuddhimagga, a book on Buddhist philosophy, which was originally started by Henry Clarke Warren. There, the young Damodar spent a year in a Grammar school and then was admitted to the Cambridge High and Latin School in 1920. He became a member of the Cambridge branch of American Boy Scouts.

It was in Cambridge that he befriended another prodigy of the time, Norbert Wiener, whose father Leo Wiener was the elder Kosambi's colleague at Harvard University. Kosambi excelled in his final school examination and was one of the few candidates who was exempt on the basis of merit from necessarily passing an entrance examination essential at the time to gain admission to Harvard University. He enrolled in Harvard in 1924, but eventually postponed his studies, and returned to India. He stayed with his father who was now working in the Gujarat University, and was in the close circles of Mahatma Gandhi.

In January 1926, Kosambi returned to the US with his father, who once again studied at Harvard University for a year and half. Kosambi studied mathematics under George David Birkhoff, who wanted him to concentrate on mathematics, but the ambitious Kosambi instead took many diverse courses excelling in each of them. In 1929, Harvard awarded him the Bachelor of Arts degree with a summa cum laude. He was also granted membership to the esteemed Phi Beta Kappa Society, the oldest undergraduate honours organisation in the United States. He returned to India soon after.

Banaras and Aligarh

He obtained the post of professor at the Banaras Hindu University (BHU), teaching German alongside mathematics. He struggled to pursue his research on his own, and published his first research paper, "Precessions of an Elliptic Orbit" in the Indian Journal of Physics in 1930.

In 1931, Kosambi married Nalini from the wealthy Madgaonkar family. It was in this year that he was hired by mathematician André Weil, then Professor of Mathematics at Aligarh Muslim University, to the post of lecturership in mathematics at Aligarh.[6] His other colleagues at Aligarh included Vijayraghavan. During his two years stay in Aligarh, he produced eight research papers in the general area of Differential Geometry and Path Spaces. His fluency in several European languages allowed him to publish some of his early papers in French, Italian and German journals in their respective languages.

Fergusson College, Pune

Marxism cannot, even on the grounds of political expediency or party solidarity, be reduced to a rigid formalism like mathematics. Nor can it be treated as a standard technique such as work on an automatic lathe. The material, when it is present in human society, has endless variations; the observer is himself part of the observed population, with which he interacts strongly and reciprocally. This means that the successful application of the theory needs the development of analytical power, the ability to pick out the essential factors in a given situation. This cannot be learned from books alone. The one way to learn it is by constant contact with the major sections of the people. For an intellectual, this means at least a few months spent in manual labour, to earn his livelihood as a member of the working class; not as a superior being, nor as a reformist, nor as a sentimental "progressive" visitor to the slums. The experience gained from living with worker and peasant, as one of them, has then to be consistently refreshed and regularly evaluated in the light of one's reading. For those who are prepared to do this, these essays might provide some encouragement, and food for thought.

— From Exasperating Essays: Exercises in Dialectical Method (1957)

Mathematics

In 1932, he joined the Deccan Education Society's Fergusson College in Pune, where he taught mathematics for 14 years.[7] In 1935, his eldest daughter, Maya was born, while in 1939, the youngest, Meera.

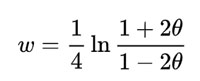

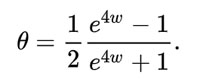

In 1944 he published a small article of 4 pages titled The Estimation of Map Distance from Recombination Values in Annals of Eugenics, in which he introduced what later came to be known as Kosambi map function. According to his equation, genetic map distance (w) is related to recombination fraction (θ) in the following way:

or, put in another way,

Kosambi's mapping function adjusts the map distance based on interference which changes the proportion of double crossovers.(To know more about this you can explore the given website https://www.academia.edu/665254/Kosambi ... g_function (edit: Bhaskarlal Datta)

One of the most important contributions of Kosambi to statistics is the widely known technique called proper orthogonal decomposition (POD). Although it was originally developed by Kosambi in 1943, it is now referred to as the Karhunen–Loève expansion. In the 1943 paper entitled 'Statistics in Function Space' presented in the Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, Kosambi presented the Proper Orthogonal Decomposition some years before Karhunen (1945) and Loeve (1948). This tool has found application to such diverse fields as image processing, signal processing, data compression, oceanography, chemical engineering and fluid mechanics. Unfortunately this most important contribution of his is barely acknowledged in most papers that utilise the POD method. In recent years though, some authors have indeed referred to it as the Kosambi-Karhunen-Loeve decomposition.[8]

Historical studies

Until 1939, Kosambi was almost exclusively focused on mathematical research, but later, he gradually started foraying into social sciences.[7] It was his studies in numismatics that initiated him into the field of historical research. He did extensive research in difficult science of numismatics. His evaluation of data was by modern statistical methods.[9] For example, he statistically analyzed the weight of thousands of punch-marked coins from different Indian museums to establish their chronological sequence and put forward his theories about the economic conditions under which these coins could have been minted.[7]

Sanskrit

He made a thorough study of Sanskrit and ancient literature, and he started his classic work on the ancient poet Bhartṛhari. He published exemplary critical editions of Bhartrihari's Śatakatraya and Subhashitas during 1945–1948.

Activism

It was during this period that he started his political activism, coming close to the radical streams in the ongoing Independence movement, especially the Communist Party of India. He became an outspoken Marxist and wrote some political articles.

Tata Institute of Fundamental Research

In the 1940s, Homi J. Bhabha invited Kosambi to join the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). Kosambi joined TIFR as Chair for Mathematics in 1946, and held the position for the next 16 years. He continued to live in his own house in Pune, and commute to Mumbai every day by the Deccan Queen train.[10]

After independence, in 1948–49 he was sent to England and to the US as a UNESCO Fellow to study the theoretical and technical aspects of computing machines. In London, he started his long-lasting friendship with Indologist and historian A.L. Basham. In the spring semester of 1949, he was a visiting professor of geometry in the Mathematics Department at the University of Chicago, where his colleague from his Harvard days, Marshall Harvey Stone, was the chair. In April–May 1949, he spent nearly two months at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, discussing with such illustrious physicists and mathematicians as J. Robert Oppenheimer, Hermann Weyl, John von Neumann, Marston Morse, Oswald Veblen and Carl Ludwig Siegel amongst others.

After his return to India, in the Cold War circumstances, he was increasingly drawn into the World Peace Movement and served as a Member of the World Peace Council. He became a tireless crusader for peace, campaigning against the nuclearisation of the world. Kosambi's solution to India's energy needs was in sharp conflict with the ambitions of the Indian ruling class. He proposed alternative energy sources, like solar power. His activism in the peace movement took him to Beijing, Helsinki and Moscow. However, during this period he relentlessly pursued his diverse research interests, too. Most importantly, he worked on his Marxist rewriting of ancient Indian history, which culminated in his book, An Introduction to the Study of Indian History (1956).

He visited China many times during 1952–62 and was able to watch the Chinese revolution very closely, making him critical of the way modernisation and development were envisaged and pursued by the Indian ruling classes. All these contributed to straining his relationship with the Indian government and Bhabha, eventually leading to Kosambi's exit from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in 1962.

Post-TIFR days

His exit from the TIFR gave Kosambi the opportunity to concentrate on his research in ancient Indian history culminating in his book, The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India, which was published in 1965 by Routledge, Kegan & Paul. The book was translated into German, French and Japanese and was widely acclaimed. He also utilised his time in archaeological studies, and contributed in the field of statistics and number theory. His article on numismatics was published in February 1965 in Scientific American.

Due to the efforts of his friends and colleagues, in June 1964, Kosambi was appointed as a Scientist Emeritus of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) affiliated with the Maharashtra Vidnyanvardhini in Pune. He pursued many historical, scientific and archaeological projects (even writing stories for children). But most works he produced in this period could not be published during his lifetime.

Kosambi died of myocardial infarction in the early hours of 29 June 1966, after being declared generally fit by his family doctor on the previous day.[5]

He was posthumously decorated with the Hari Om Ashram Award by the government of India's University Grant Commission in 1980.

His friend A.L. Basham, a well-known indologist, wrote in his obituary:

At first it seemed that he had only three interests, which filled his life to the exclusion of all others — ancient India, in all its aspects, mathematics and the preservation of peace. For the last, as well as for his two intellectual interests, he worked hard and with devotion, according to his deep convictions. Yet as one grew to know him better one realized that the range of his heart and mind was very wide...In the later years of his life, when his attention turned increasingly to anthropology as a means of reconstructing the past, it became more than ever clear that he had a very deep feeling for the lives of the simple people of Maharashtra.[11]

Kosambi's historiography

Certain opponents of Marxism dismiss it as an outworn economic dogma based upon 19th century prejudices. Marxism never was a dogma. There is no reason why its formulation in the 19th century should make it obsolete and wrong, any more than the discoveries of Gauss, Faraday and Darwin, which have passed into the body of science... The defense generally given is that the Gita and the Upanishads are Indian; that foreign ideas like Marxism are objectionable. This is generally argued in English the foreign language common to educated Indians; and by persons who live under a mode of production (the bourgeois system forcibly introduced by the foreigner into India.) The objection, therefore seems less to the foreign origin than to the ideas themselves which might endanger class privilege. Marxism is said to be based upon violence, upon the class-war in which the very best people do not believe nowadays. They might as well proclaim that meteorology encourages storms by predicting them. No Marxist work contains incitement to war and specious arguments for senseless killing remotely comparable to those in the divine Gita.

— From Exasperating Essays: Exercises in Dialectical Method (1957)

Although Kosambi was not a practising historian, he wrote four books and sixty articles on history: these works had a significant impact on the field of Indian historiography.[12] He understood history in terms of the dynamics of socio-economic formations rather than just a chronological narration of "episodes" or the feats of a few great men – kings, warriors or saints. In the very first paragraph of his classic work, An Introduction to the Study of Indian History, he gives an insight into his methodology as a prelude to his life work on ancient Indian history:

"The light-hearted sneer “India has had some episodes, but no history“ is used to justify lack of study, grasp, intelligence on the part of foreign writers about India’s past. The considerations that follow will prove that it is precisely the episodes — lists of dynasties and kings, tales of war and battle spiced with anecdote, which fill school texts — that are missing from Indian records. Here, for the first time, we have to reconstruct a history without episodes, which means that it cannot be the same type of history as in the European tradition."[13]

According to A. L. Basham, "An Introduction to the Study of Indian History is in many respects an epoch making work, containing brilliantly original ideas on almost every page; if it contains errors and misrepresentations, if now and then its author attempts to force his data into a rather doctrinaire pattern, this does not appreciably lessen the significance of this very exciting book, which has stimulated the thought of thousands of students throughout the world."[11]

Professor Sumit Sarkar says: "Indian Historiography, starting with D.D. Kosambi in the 1950s, is acknowledged the world over – wherever South Asian history is taught or studied – as quite on a par with or even superior to all that is produced abroad. And that is why Irfan Habib or Romila Thapar or R.S. Sharma are figures respected even in the most diehard anti-Communist American universities. They cannot be ignored if you are studying South Asian history."[14]

In his obituary of Kosambi published in Nature, J. D. Bernal had summed up Kosambi's talent as follows: "Kosambi introduced a new method into historical scholarship, essentially by application of modern mathematics. By statistical study of the weights of the coins, Kosambi was able to establish the amount of time that had elapsed while they were in circulation and so set them in order to give some idea of their respective ages."

Legacy

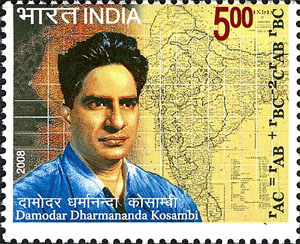

Kosambi on a 2008 stamp of India

Kosambi is an inspiration to many across the world, especially to Sanskrit philologists[15] and Marxist scholars. He deeply influenced Indian historiography.[16] The Government of Goa has instituted the annual D.D. Kosambi Festival of Ideas since February 2008 to commemorate his birth centenary.[17]

Historian Irfan Habib said, "D. D. Kosambi and R.S. Sharma, together with Daniel Thorner, brought peasants into the study of Indian history for the first time."[18]

Kosambi was an atheist.[19]

India Post issued a commemorative postage stamp on 31 July 2008 to honour Kosambi.[20][21]

Books by D.D. Kosambi

Works on history and society

• 1956 An Introduction to the Study of Indian History (Popular Book Depot, Bombay)

• 1957 Exasperating Essays: Exercise in the Dialectical Method (People's Book House, Poona)

• 1962 Myth and Reality: Studies in the Formation of Indian Culture (Popular Prakashail, Bombay)

• 1965 The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline (Routledge & Kegan Paul, London)

• 1981 Indian Numismatics (Orient Blackswan, New Delhi)

• 2002 D.D. Kosambi: Combined Methods in Indology and Other Writings – Compiled, edited and introduced by Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (Oxford University Press, New Delhi). Pdf on archive.org

• 2009 The Oxford India Kosambi – Compiled, edited and introduced by Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya (Oxford University Press, New Delhi)

• 2014 Unsettling The Past, edited by Meera Kosambi (Permanent Black, Ranikhet)

• 2016 Adventures into the Unknown: Essays, edited by Ram Ramaswamy (Three Essays Collective, New Delhi)

Edited works

• 1945 The Satakatrayam of Bhartrhari with the Comm. of Ramarsi, edited in collaboration with Pt. K. V. Krishnamoorthi Sharma (Anandasrama Sanskrit Series, No.127, Poona)

• 1946 The Southern Archetype of Epigrams Ascribed to Bhartrhari (Bharatiya Vidya Series 9, Bombay) (First critical edition of a Bhartrhari recension.)

• 1948 The Epigrams Attributed to Bhartrhari (Singhi Jain Series 23, Bombay) (Comprehensive edition of the poet's work remarkable for rigorous standards of text criticism.)

• 1952 The Cintamani-saranika of Dasabala; Supplement to Journal of Oriental Research, xix, pt, II (Madras) (A Sanskrit astronomical work which shows that King Bhoja of Dhara died in 1055–56.)

• 1957 The Subhasitaratnakosa of Vidyakara, edited in collaboration with V.V. Gokhale (Harvard Oriental Series 42)

Mathematical and scientific publications

In addition to the papers listed below, Kosambi wrote two books in mathematics, the manuscripts of which have not been traced. The first was a book on path geometry that was submitted to Marston Morse in the mid-1940s and the second was on prime numbers, submitted shortly before his death. Unfortunately, neither book was published. The list of articles below is complete but does not include his essays on science and scientists, some of which have appeared in the collection Science, Society, and Peace (People's Publishing House, 1995). Four articles (between 1962 and 1965) are written under the pseudonym S. Ducray.

• 1930 Precessions of an elliptical orbit, Indian Journal of Physics, 5, 359–364

• 1931 On a generalization of the second theorem of Bourbaki, Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences, U. P., 1, 145–147

• 1932 Modern differential geometries, Indian Journal of Physics, 7, 159–164

• 1932 On differential equations with the group property, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 19, 215–219

• 1932 Geometrie differentielle et calcul des variations, Rendiconti della Reale Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 16, 410–415 (in French)

• 1932 On the existence of a metric and the inverse variational problem, Bulletin of the Academy of Sciences, U. P., 2, 17–28

• 1932 Affin-geometrische Grundlagen der Einheitlichen Feld–theorie, Sitzungsberichten der Preussische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Physikalisch-mathematische klasse, 28, 342–345 (in German)

• 1933 Parallelism and path-spaces, Mathematische Zeitschrift, 37, 608–618

• 1933 Observations sur le memoire precedent, Mathematische Zeitschrift, 37, 619–622 (in French)

• 1933 The problem of differential invariants, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 20, 185–188

• 1933 The classification of integers, Journal of the University of Bombay, 2, 18–20

• 1934 Collineations in path-space, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 1, 68–72

• 1934 Continuous groups and two theorems of Euler, The Mathematics Student, 2, 94–100

• 1934 The maximum modulus theorem, Journal of the University of Bombay, 3, 11–12

• 1935 Homogeneous metrics, Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, 1, 952–954

• 1935 An affine calculus of variations, Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, 2, 333–335

• 1935 Systems of differential equations of the second order, Quarterly Journal of Mathematics (Oxford), 6, 1–12

• 1936 Differential geometry of the Laplace equation, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 2, 141–143

• 1936 Path-spaces of higher order, Quarterly Journal of Mathematics (Oxford), 7, 97–104

• 1936 Path-geometry and cosmogony, Quarterly Journal of Mathematics (Oxford), 7, 290–293

• 1938 Les metriques homogenes dans les espaces cosmogoniques, Comptes rendus de l’Acad ́emie des Sciences, 206, 1086–1088 (in French)

• 1938 Les espaces des paths generalises qu’on peut associer avec un espace de Finsler, Comptes rendus de l’Acad ́emie des Sciences, 206, 1538–1541 (in French)

• 1939 The tensor analysis of partial differential equations, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 3, 249–253 (1939); Japanese version of this article in Tensor, 2, 36–39

• 1940 A statistical study of the weights of the old Indian punch-marked coins, Current Science, 9, 312–314

• 1940 On the weights of old Indian punch-marked coins, Current Science, 9, 410–411

• 1940 Path-equations admitting the Lorentz group, Journal of the London Mathematical Society, 15, 86–91

• 1940 The concept of isotropy in generalized path-spaces, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 4, 80–88

• 1940 A note on frequency distribution in series, The Mathematics Student, 8, 151–155

• 1941 A bivariate extension of Fisher's Z–test, Current Science, 10, 191–192

• 1941 Correlation and time series, Current Science, 10, 372–374

• 1941 Path-equations admitting the Lorentz group–II, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 5, 62–72

• 1941 On the origin and development of silver coinage in India, Current Science, 10, 395–400

• 1942 On the zeros and closure of orthogonal functions, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 6, 16–24

• 1942 The effect of circulation upon the weight of metallic currency, Current Science, 11, 227–231

• 1942 A test of significance for multiple observations, Current Science, 11, 271–274

• 1942 On valid tests of linguistic hypotheses, New Indian Antiquary, 5, 21–24

• 1943 Statistics in function space, Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 7, 76–88

• 1944 The estimation of map distance from recombination values, Annals of Eugenics, 12, 172–175

• 1944 Direct derivation of Balmer spectra, Current Science, 13, 71–72

• 1944 The geometric method in mathematical statistics, American Mathematical Monthly, 51, 382–389

• 1945 Parallelism in the tensor analysis of partial differential equations, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 51, 293–296

• 1946 The law of large numbers, The Mathematics Student, 14, 14–19

• 1946 Sur la differentiation covariante, Comptes rendus de l’Acad ́emie des Sciences, 222, 211–213 (in French)

• 1947 An extension of the least–squares method for statistical estimation, Annals of Eugenics, 18, 257–261

• 1947 Possible Applications of the Functional Calculus, Proceedings of the 34th Indian Science Congress. Part II: Presidential Addresses, 1–13

• 1947 Les invariants differentiels d’un tenseur covariant a deux indices, Comptes rendus de l’Acad ́emie des Sciences, 225, 790–92 (in French)

• 1948 Systems of partial differential equations of the second order, Quarterly Journal of Mathematics (Oxford), 19, 204–219

• 1949 Characteristic properties of series distributions, Proceedings of the National Institute of Science of India, 15, 109–113

• 1949 Lie rings in path-space, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), 35, 389–394

• 1949 The differential invariants of a two-index tensor, Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 55, 90–94

• 1951 Series expansions of continuous groups, Quarterly Journal of Mathematics (Oxford, Series 2), 2, 244–257

• 1951 Seasonal variations in the Indian birth–rate, Annals of Eugenics, 16, 165–192 (with S. Raghavachari)

• 1952 Path-spaces admitting collineations, Quarterly Journal of Mathematics (Oxford, Series 2), 3, 1–11

• 1952 Path-geometry and continuous groups, Quarterly Journal of Mathematics (Oxford, Series 2), 3, 307–320

• 1954 Seasonal variations in the Indian death–rate, Annals of Human Genetics, 19, 100–119 (with S. Raghavachari)

• 1954 The metric in path-space, Tensor (New Series), 3, 67–74

• 1957 The method of least–squares, Advancement in Mathematics, 3, 485–491 (in Chinese)

• 1958 Classical Tauberian theorems, Journal of the Indian Society of Agricultural Statistics, 10, 141–149

• 1958 The efficiency of randomization by card–shuffling, Journal of the Royal Statistics Society, 121, 223–233 (with U. V. R. Rao)

• 1959 The method of least–squares, Journal of the Indian Society of Agricultural Statistics, 11, 49–57

• 1959 An application of stochastic convergence, Journal of the Indian Society of Agricultural Statistics, 11, 58–72

• 1962 A note on prime numbers, Journal of the University of Bombay, 31, 1–4 (as S. Ducray)

• 1963 The sampling distribution of primes, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), 49, 20–23

• 1963 Normal Sequences, Journal of the University of Bombay, 32, 49–53 (as S. Ducray)

• 1964 Statistical methods in number theory, Journal of the Indian Society of Agricultural Statistics, 16, 126–135

• 1964 Probability and prime numbers, Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, 60, 159–164 (as S. Ducray)

• 1965 The sequence of primes, Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences, 62, 145–149 (as S. Ducray)

• 1966 Numismatics as a Science, Scientific American, February 1966, pages 102–111

• 2016 Selected Works in Mathematics and Statistics, ed. Ramakrishna Ramaswamy, Springer. (Posthumous publication)

See also

• Marxist historiography

References

1. Vinod, K.K. (June 2011). "Kosambi and the genetic mapping function". Resonance. 16 (6): 540–550. doi:10.1007/s12045-011-0060-x. S2CID 84289582.

2. Raju, C.K. (2009), "Kosambi the Mathematician", Economic and Political Weekly, 44 (20): 33–45

3. Kosambi, D. D. (1943), "Statistics in Function Space", Journal of the Indian Mathematical Society, 7: 76–88, MR 0009816

4. Sreedharan, E. (2004). A Textbook of Historiography: 500 BC to AD 2000. Orient Blackswan. p. 469. ISBN 978-81-250-2657-0.

5. V. V. Gokhale 1974, p. 1.

6. Weil, André; Gage, Jennifer C (1992). The apprenticeship of a mathematician. Basel, Switzerland: Birkhäuser Verlag. ISBN 9783764326500. OCLC 24791768.

7. V. V. Gokhale 1974, p. 2.

8. Steward, Jeff (20 May 2009). The Solution of a Burgers' Equation Inverse Problem with Reduced-Order Modeling Proper Orthogonal Decomposition (Master's thesis). Tallahassee, Florida: Florida State University. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

9. Sreedharan, E. (2007). A Manual of Historical Research Methodology. Thiruvananthapuram, India: Centre for South Indian Studies. ISBN 9788190592802. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

10. V. V. Gokhale 1974, p. 3.

11. Basham, A. L.; et al. (1974). "'Baba': A Personal Tribute". In Sharma, Ram Sharan (ed.). Indian society: historical probings, in memory of D. D. Kosambi. New Delhi, India: People's Publishing House. pp. 16–19. OCLC 3206457.

12. R. S. Sharma (1974) [1958]. "Preface". Indian Society: Historical Probings in memory of D. D. Kosambi. Indian Council of Historical Research / People's Publishing House. p. vii. ISBN 978-81-7007-176-1.

13. Kosambi, Damodar Dharmanand (1975) [1956]. An introduction to the study of Indian history(Second ed.). Mumbai, India: Popular Prakashan. p. 1.

14. "Not a question of bias". 17 – Issue 05. Frontline. 4–17 March 2000. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

15. Pollock, Sheldon (26 July 2008). "Towards a Political Philology" (PDF). Economic & Political Weekly. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

16. Sreedharan, E. (2004). A Textbook of Historiography: 500 BC to AD 2000. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-2657-0.

17. "D.D. Kosambi festival from February 5". The Hindu. 20 January 2011. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

18. Habib, Irfan (2007). Essays in Indian History (Seventh reprint). Tulika. p. 381 (at p 109). ISBN 978-81-85229-00-3.

19. Padgaonkar, Dileep (8 February 2013). "Kosambi's uplifting idea Of India". Times of India Blog. Archived from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017. Both were pious — his mother a Hindu, his father a Buddhist — while he himself remained an atheist.

20. Vaidya, Abhay (11 December 2008). "Finally, a stamp in DD Kosambi's honour". Syndication DNA. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

21. "Stamps 2008". Indian Postage Stamps. Ministry of Communication, Government of India. Archived from the original on 10 April 2017. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

Bibliography

• V. V. Gokhale (1974) [1958]. "Damodar Dharmanand Kosambi". In R. S. Sharma (ed.). Indian Society: Historical Probings in memory of D. D. Kosambi. Indian Council of Historical Research / People's Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7007-176-1.

A collection entitled "Science, Society And Peace" of Prof DD Kosambi's essays has been published in the 1980's [exact year to be mentioned...] by Academy of Political & Social Studies, Akshay, 216, Narayan Peth,Pune 411030. Republished by People's Publishing House, New Delhi in 1995]

Further reading

• The Many Careers of D.D. Kosambi edited by D.N. Jha, 2011 Leftword Books. Full text on archive.org

• Towards a Political Philology: D.D. Kosambi and Sanskrit (2008) by Sheldon Pollock, EPW.

• Early Indian History and the Legacy of D.D. Kosambi by Romila Thapar. Resonance, June 2011.

• Kosambi, Marxism and Indian History by Irfan Habib. EPW, 26 July 2008. Pdf.

• R.S. Sharma and Vivekanand Jha, Indian Society, Historical Probings (in memory of D. D. Kosambi), People's Publishing House, New Delhi, 1974.

• J.D.Bernal: obituary D.D.Kosambi. Nature, 1966 Sept.3; 211: 1024.

External links

• Steps in Science. Essay by D.D. Kosambi

• "Baba": A Personal Tribute by A.L. Basham

• My Friendship with D. D. Kosambi by Daniel H. H. Ingalls

• D.D. Kosambi: Father of Scientific Indian History by Dale Riepe

• Video. Romila Thapar at D. D. Kosambi Festival of Ideas 2008, Goa, Part-1, Part-2