Chapter XVIII: The Conquest of the Far East, Excerpt from "History of Greece for Beginners"by J. B. Bury, M.A., Hon. Litt. D. Oxon. and Durham; Hon. LL.D. Edinburgh and Glasgow; Corresponding Member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg; Fellow of Trinity College, Dublin, and of King's College, Cambridge; Regius Professor of Modern History in the University of Cambridge

1907

CHAPTER XVIII: THE CONQUEST OF THE FAR EAST

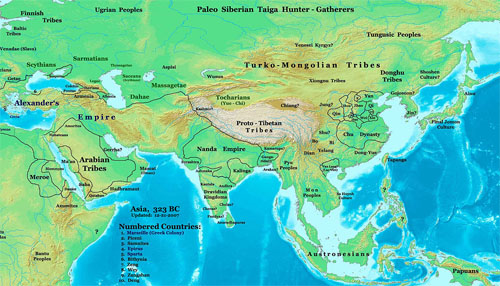

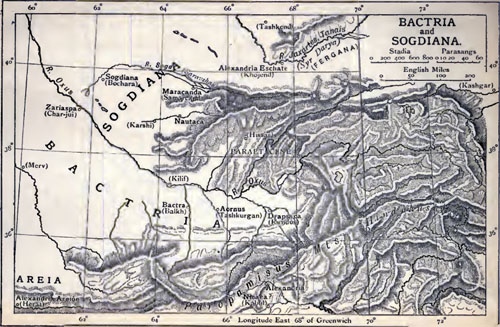

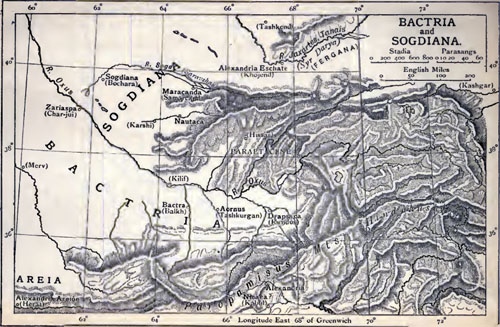

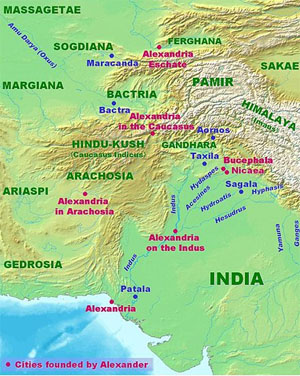

SECT. I. Hyrcania, Areia, Bactria, Sogdiana. The murderers of Darius fled -- Bessus to Bactria, Nabarzanes to Hyrcania. Alexander could not pursue Bessus while Nabarzanes was behind him in the Caspian region, and therefore

his first movement was to cross the Elburz chain of mountains which separate the south Caspian shores from Parthia, and subdue the lands of the Tapuri and Mardi. The Persian officers who had retreated into these regions submitted, and were received with favour; the life of Nabarzanes was spared. The Greek mercenaries who had found refuge in the Tapurian mountains capitulated. All who had entered the Persian service, before the Synedrion of Corinth had pledged Greece to the cause of Macedon, were released; the rest were compelled to serve in the Macedonian army. Alexander sent orders to Parmenio to go forth from Ecbatana and take possession of the Cadusian territory on the south-western side of the Caspian. He himself, having rested a fortnight at Zadracarta and held athletic games, marched eastward to Susia, a town in the north of Areia, and was met there by Satibarzanes, governor of Areia, who was confirmed in his satrapy. Here

the news arrived that Bessus had assumed the style of Great King with the name of Artaxerxes, and was wearing his turban "erect." Alexander started at once on the road to Bactria. But he had not gone far when he was overtaken by the news that Satibarzanes had revolted behind him. Hurrying back in forced marches with a part of his army, Alexander appeared before Artocoana, the capital of Areia, in two days. There was little resistance, and the conqueror marched southwards to Drangiana. His road can hardly be doubtful -- the road which leads by Herat into Seistan. And

it is probable that Herat is the site of the city which Alexander founded to be the capital and stronghold of the new province, Alexandria of the Areians. The submission of Drangiana was made without a blow.

At Prophthasia, the capital of the Drangian land, it came to Alexander's ears that Philotas, the son of Parmenio, was conspiring against his life. The king called an assembly of the Macedonians and stated the charges against the general. Philotas admitted that he had known of a plot to murder Alexander and said nothing about it; but this was only one of the charges against him. The Macedonians found Philotas guilty, and he was pierced by their javelins. The son dead, it seemed dangerous to let the father live, whether he was involved or not in the treasonable designs of Philotas. A messenger was dispatched with all speed to Media, bearing commands to some of the captains of Parmenio's army to put the old general to death. It was an arbitrary act of precaution against merely suspected disloyalty; there seem to have been no proofs against Parmenio, and there was certainly no trial.

329 B.C.In the meantime Alexander, instead of retracing his steps and following the route to Bactria, resolved to fetch a circle.

Marching through Afghanistan, subduing it as he went, he would cross the Hindu-Kush mountains and descend on the plain of the Oxus from the east. First he advanced southwards to secure Seistan and the northwestern regions of Baluchistan, then known as Gedrosia, wintering among the Ariaspae, a peaceful and friendly people whom the Greeks called "Benefactors." A Gedrosian satrapy was constituted with its capital at Pura. When spring came, Alexander pushed north-eastward up the valley of the Halmand.

The chief city which he founded in Arachosia was probably on the site of Candahar, which seems to be a corruption of its name, Alexandria. The way led on over the mountains, past Ghazni, into the valley of the upper waters of the Cabul River, and Alexander came to the foot of the high range of the Hindu-Kush. The whole massive complex of mountains which diverge from the roof of the world, dividing southern from central, eastern from western Asia the Pamirs, the Hindu-Kush, and the Himalayas were grouped by the Greeks under the general name of Caucasus. But the Hindu-Kush was distinguished by the special name of Paropanisus, while the Himalayas were called the Imaus.

At the foot of the Hindu-Kush he spent the winter, and founded another Alexandria to secure this region, somewhere to the north of Cabul; it was distinguished as Alexandria of the Caucasus. The crossing of the Caucasus, undertaken in the early spring, was an achievement which seems to have fallen little short of Hannibal's passage of the Alps. The soldiers had to content themselves with raw meat and the herb of silphion as a substitute for bread. At length they reached Drapsaca, high up on the northern slope -- the frontier fortress of Bactria.

Having rested his way-worn army, Alexander went down by the stronghold of Aornus into the plain and marched to Bactra, now Balkh.

The pretender, Bessus Artaxerxes, had stripped and wasted eastern Bactria up to the foot of the mountains, for the purpose of checking the progress of the invading army; but he fled across the Oxus when Alexander drew near. Another province was added without a blow to the Macedonian empire. Alexander lost no time in pursuing the fugitive into Sogdiana. This is the country which lies between the streams of the Oxus and the Jaxartes. It was called Sogdiana from the river Sogd, which loses itself in the sands of the desert before it approaches the waters of the Oxus. Bessus had burned his boats, and when Alexander, after a weary march of two or three days through the hot desert, arrived at the banks of the Oxus, he was forced to transport his army by the primitive vehicle of skins, which the natives of Central Asia still use. Alexander's soldiers, however, instead of inflating the sheep-skins with air, stuffed them with rushes. They crossed the river at Kilif and advanced to Maracanda, easily recognised as Samarcand.

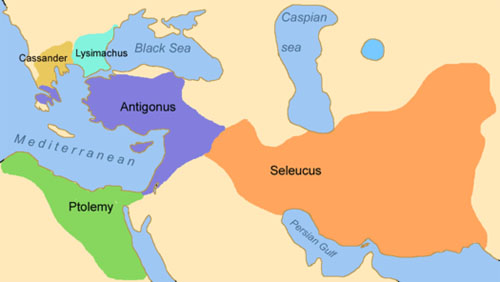

The Sogdian allies of Bessus, thinking to save their country, sent a message offering to surrender the usurper. The king sent Ptolemy, son of Lagus, with 6000 men to secure Bessus. By Alexander's orders he was placed, naked and fettered, on the right side of the road by which the army was marching. He was then scourged and sent to Bactra to await his doom. 328 B.C. Bactria and Sogdiana

Bactria and SogdianaBut Alexander did not arrest his march;

he had made up his mind to annex Sogdiana. Not the Oxus but the Jaxartes was to be the northern limit of his empire. Having seized and garrisoned Samarcand, the army pushed on north-eastward by the unalterable road which nature has marked out. The road reaches the Jaxartes where that river issues from the chilly vale of Fergana and deflects its course to flow through the steppes. It was a point of the highest importance; for Fergana forms the vestibule of the great gate of communication between south-western Asia and China the pass over the Tian-shan mountains, which descends on the other side into the land of Kashgar. Here Alexander, with strategic insight, resolved to fix the limit of his empire, and

on the banks of the river he founded a new city which, was known as Alexandria Eschate (the Ultimate), which is now Khodjend. The conqueror, judging from the ease with which he had come and conquered Arachosia, and Bactria, seems not to have conceived that it might be otherwise beyond the Oxus. But

as he was designing his new city, Alexander received the news that the Sogdians were up in arms behind him, and the garrison of Samarcand was besieged in the citadel. A message had gone forth into the western wastes, and the Massagetae and other Scythian tribes were flocking to drive out the intruder. It was a dangerous moment for Alexander. He first turned to recover the Sogdian fortresses, and in two days he had taken and burned five of them; the others capitulated, and the indwellers of all these places were led in chains to take part in peopling the new Alexandria. The next task should have been the relief of Samarcand, but Alexander found himself confronted by a new danger. The Scythians were pouring down to the banks of the Jaxartes, ready to cross the stream and harass the Macedonians in the rear. It was impossible to move until they had been repelled and the passage of the river secured. The walls of Alexandria Eschate were hastily constructed of unburnt clay and the place made fit for habitation in the short space of twenty days. Meanwhile the northern bank was lined by the noisy and jeering hordes of the barbarians, and Alexander determined to cross the river. Bringing up his missile-engines to the shore, he dismayed the shepherds, who, when stones and darts began to fall among them from such a distance and unhorsed one of their champions, retreated some distance from the bank. The army seized the moment to cross;

the Scythians were routed, and Alexander, at the head of his cavalry, pursued them far into the steppes. Then, relieving Samarcand by a forced desert march, the king swept on to Sogdiana, ravaging the land; then marching south-westward to the Oxus, he crossed into western Bactria and spent the winter at Zariaspa.

327 B.C.At Zariaspa, Bessus was formally tried for the murder of Darius, and was condemned to have his nose and ears cut off and he taken to Ecbatana to die on the cross. The Greeks, like ourselves, regarded mutilation as a barbarous punishment, but Alexander saw that he must meet the orientals on their own ground; he must become their king in their own way. The surest means of planting Hellenism in their midst was to begin by taking account sympathetically of their prejudices. Alexander therefore assumed the state of Great King, surrounded himself with Eastern forms and pomp, exacted self-abasement in his presence from oriental subjects, and adopted the maxim that the king's person was divine. He was the successor of Darius, and it was therefore an act of deliberate policy that he punished the king-slayer in Eastern fashion. The misfortune was that

Alexander's assumption of oriental state and the favour which he showed to the Persians were highly unpopular with the Macedonians. Though they were attached to their king, and proud of the conquests which they had helped him to achieve, they felt that he was no longer the same to them as when he had led them to victory at the Granicus. His exaltation over obeisant orientals had changed him, and the execution of his trusted general Parmenio was felt to be significant of the change.

327 B.C.These feelings of discontent accidentally found a mouth-piece about this time.

Rebellious movements in Sogdiana brought Alexander over the Oxus again before the winter was over, and he spent some time at Samarcand. One of the most unfortunate consequences of the long-protracted sojourn in the regions of the Oxus was the

increase of drunkenness in the army. The excessively dry atmosphere in summer produces an intolerable and frequent thirst; and it was inevitable that the Macedonians should slake it by wine, if they would not sicken themselves by the bad water of the country.

Alexander's potations became deep and habitual from this time forth. One night in the fortress of Samarcand the carouse lasted far into the night. Greek men of letters, who accompanied the army, sang the praises of Alexander, exalting him above the Dioscuri, whose feast he was celebrating on this day.

Clitus, his foster-brother, flushed with wine, suddenly sprang up to denounce the blasphemy, and, once he had begun, the current of his feelings swept him on. It was to the Macedonians, he said -- to men like Parmenio and Philotas -- that Alexander owed his victories; he himself had saved Alexander's life at the Granicus. Alexander started to his feet and called in Macedonian for his hypaspists; none obeyed his drunken orders; Ptolemy and other banqueters forced Clitus out of the hall, while others tried to restrain the king. But presently Clitus made his way back and shouted from the doorway some insulting verses of Euripides, signifying that the army does the work and the general reaps the glory.

The king leapt up, snatched a spear from the hand of a guardsman, and transfixed his foster-brother. An agony of remorse followed. For three days the murderer lay in his tent, without sleep or food, cursing himself as the assassin of his friends.

There were more hostilities in western Bactria and western Sogdiana, until at last, overawed by Alexander's success, the Scythians, in order to win his favour, slew Spitamenes, their chief leader. It only remained to reduce the rugged south-eastern regions of Sogdiana. The Sogdian Rock, which commands the pass into these regions, was occupied by Oxyartes, and a band of Macedonian soldiers captured it by an arduous night-climb.

Among the captives was Roxane, the daughter of Oxyartes; and the love of Alexander was attracted by the beauty and manners of the Sogdian maiden. Notwithstanding the adverse comment which such a condescension would excite among the proud Macedonians, he resolved to make her his wife, and, on his return to Bactra, he celebrated the nuptials -- a union of Asia and Europe.

About this time an attempt seems to have been made to render uniform the court ceremonial, and enforce upon the Macedonians the obeisances demanded from Persian nobles. Callisthenes, nephew of Aristotle, who was composing a history of Alexander's campaigns, was prominent in opposing the change, and fell into disfavour. One of his duties was to educate the pages, the noble Macedonian youths who attended on the king's person; and over some of these Callisthenes had great influence.

One day at a boar-hunt a page named Hermolaus committed the indiscretion of forestalling the king in slaying the beast; and for this breach of etiquette he was flogged and deprived of his horse. Smarting under the dishonour, Hermolaus plotted with some of his comrades to slay Alexander in his sleep. But the plot was betrayed. The conspirators were arrested, and put to death by the sentence of the whole army. Callisthenes was hanged on the charge of being an accomplice. Before the end of summer, Alexander bade farewell to Bactria and set forth to the conquest of India.

In three years since the death of Darius, the western conqueror had subdued Afghanistan, and cast his yoke over the herdsmen of the north as far as the river Jaxartes. He was the first European invader and conqueror of the regions beyond the Oxus, anticipating by more than two thousand years Russia's recent conquests. His next enterprise forestalled our own conquest of north-western India.

SECT. 2. The Conquest of India. In returning to Afghanistan,

Alexander seems to have followed the main road from Balkh to Cabul, which, if he had not refounded, he had at all events renamed, Nicaea. Here he stayed till the middle of November, preparing for further advance.

He had left a large detachment of his army in Bactria, but he had enrolled a still larger force 30,000 of the Asiatics of those regions. The host with which he was now to descend upon India must have been at least twice as numerous as the army with which he had crossed the Hellespont seven years before.

During these years

Alexander's camp was his court and capital, the political centre of his empire, a vast city rolling along over mountain and river through Central Asia. Men of all trades and callings were there: craftsmen of every kind, engineers, physicians, and seers; cheapmen and money-changers; literary men, poets, musicians, athletes, jesters; secretaries, clerks, court attendants;

a host of women and slaves. A Court Diary was regularly kept in imitation of the court journal of Persia by Eumenes of Cardia, who conducted the king's political correspondence.

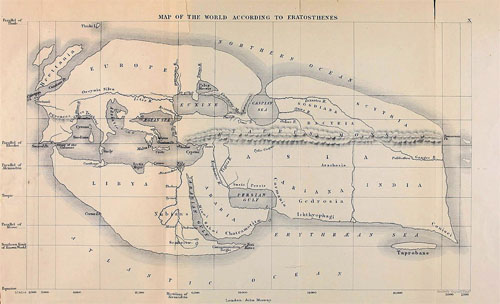

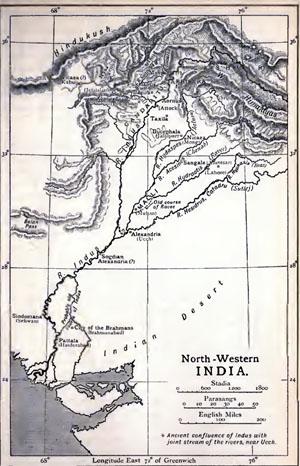

Alexander had no idea of the shape or extent of the Indian peninsula, and his notion of the Indian conquest was probably confined to the basins of the Cophen (R. Cabul) and the Indus.

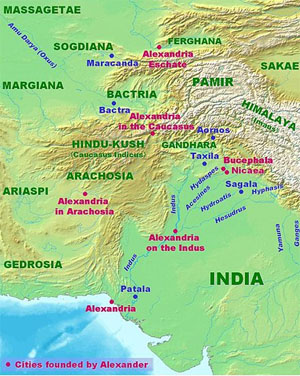

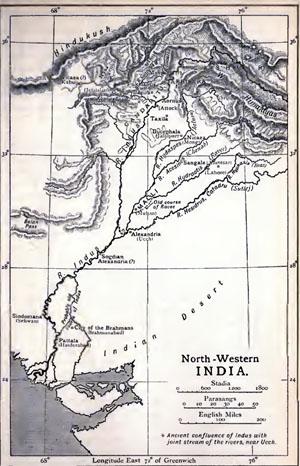

The stories that were told about the wonders of India excited the curiosity of the Greek invaders. It was a land of righteous folks, of strange beasts and plants, of surpassing wealth in gold and gems. It was supposed to be the ultimate country on the eastern side of the world, bounded by Ocean's stream. 327 B.C. Fig. 91: North-Western IndiaAt this time north-western India was occupied by a number of small principalities

Fig. 91: North-Western IndiaAt this time north-western India was occupied by a number of small principalities. The northern districts of the land between the Indus and the Hydaspes (R. Jhelum) were ruled by Omphis, whose capital was at Taxila near the Indus. His brother Abisares was the ruler of Hazara and the adjacent parts of Cashmir.

Beyond the Hydaspes was the powerful kingdom of Porus, who held sway as far as the Acesines, which we know as the Chenab, the next of the "Five Rivers."

East of the Chenab, in the lands of the Ravee and the Beas, were other small principalities, and also free "kingless" peoples, who owned no master. These states had no tendency to unity or combination. An invader, therefore, had no common resistance to fear; and he could be assured that many would welcome him out of hatred for their neighbours.

The prince of Taxila paid homage to Alexander at Nicaea, and promised his aid in subduing India. Alexander's direct road from the high plain of Cabul into the Punjab lay along the right bank of the Cophen or Cabul River, through the great gate of the Khyber Pass. But

it was impossible to advance to the Indus without securing his communications, and for this purpose it was needful to subjugate the river-valleys to the left of the Cabul, among the huge Western spurs of the Himalaya mountains. For the purposes of this campaign Alexander divided his army. Hephaestion advanced by the Khyber Pass, with orders to construct a bridge across the Indus. The king, with the rest of the army, including the light troops, plunged into the difficult country north of the river; and

the winter was spent in warfare with the hardy hill-folks in the district of the Kunar, in remote Chitral, and in the Panjkar and Swat valleys. After this severe winter campaign the army rested on the west bank of the Indus until spring had begun, and

then, with the solemnity of games and sacrifices, crossed the river to Taxila, whose prince and other lesser princes met Alexander with obsequious pomp. A new satrapy, embracing the lands west of the Indus, was now established and entrusted to Philip, son of Machatas; Macedonian garrisons were placed in Taxila and some other places east of the Indus, and Philip was charged with the general command of these troops. This shows the drift of Alexander's policy. The Indus was to be the eastern boundary of his direct sway; beyond the Indus, he purposed to create no new provinces, but only to form a system of protected states.

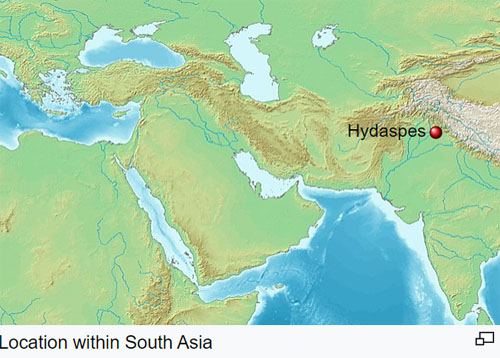

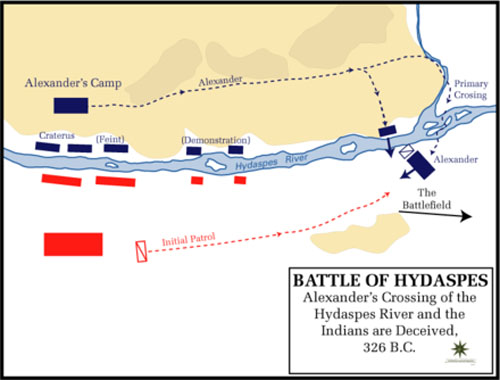

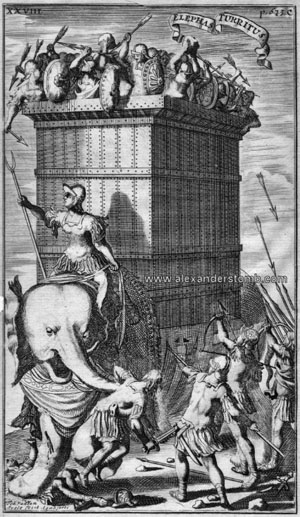

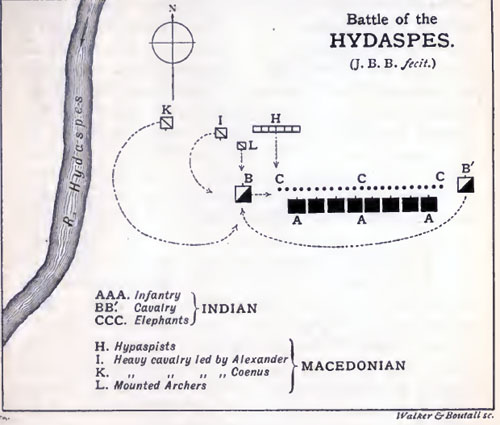

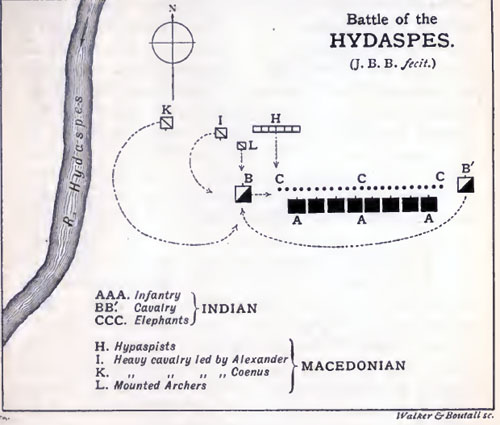

326 B.C.Alexander then marched to the Hydaspes. Prince Porus having gathered an army from thirty to forty thousand strong, was encamped on the left bank of the river, to contest the crossing. After a march, which was made slow and toilsome by the heavy tropical rain, the invaders encamped on the right bank of the river, and saw the lines of Porus on the opposite shore, protected by a multitude of elephants. It was useless to think of crossing in the face of this host; for the horses, who could not endure the smell and noise of the elephants, would certainly have been drowned; and the men would have found it almost impossible to land, amid showers of darts, on the slimy, treacherous edge of the stream. All the fords in the neighbourhood were watched. Alexander adopted measures to deceive and puzzle the enemy. Each night the Macedonian camp was in motion as if for crossing; each night the Indians stood long hours in the wind and rain. Alexander meanwhile was maturing a plan which he was able to carry out when he had put Porus off his guard.

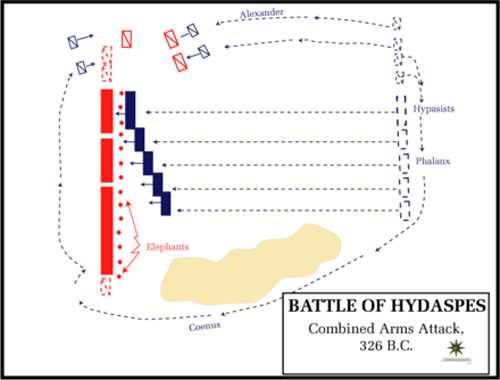

About sixteen miles upwards from the camp the Hydaspes makes a bend westward, and opposite the jutting angle a thickly-wooded island rose amid the stream, while a dense wood covered the right shore. Here Alexander determined to cross. He caused the boats to be conveyed thither in pieces and remade in the shelter of the wood; he had prepared skins stuffed with straw. When the time came he led a portion of his troops to the wooded promontory, marching at a considerable distance from the river in order to avoid the observation of the enemy. A sufficient force was left to guard the camp under the command of Craterus. The king arrived at the appointed spot later in the evening, and throughout the wet stormy night he directed the preparations for passing the swollen stream. Before dawn the passage began. Alexander led the way in a barque of thirty oars, and the island was safely passed; but land was hardly reached before they were descried by Indian scouts. At last the whole force was safely landed on the bank, and Alexander ordered his men for the coming battle the third of the three great battles of his life. It was to be won without any heavy infantry; he had with him only 6000 hypaspists, about 4000 light foot, 5000 cavalry, including 1000 Scythian archers.

Taking all the cavalry with him he rode rapidly forward towards the camp of Porus.  Fig. 92: Battle of the Hydaspes

Fig. 92: Battle of the HydaspesBut Porus was advancing with his main army, having left a small force to guard the river bank against Craterus. When he reached sandy ground, suitable for the movements of his cavalry and war-chariots, he drew up his line of battle. In front of all he arranged two hundred elephants at intervals of 100 feet, and at some distance behind them his infantry, who numbered 20,000 if not more. On the wings he placed his cavalry -- perhaps 4000. Alexander waited for the hypaspists to come up, and drew them up opposite to the elephants. It was impossible to attack in front, for neither horse nor foot could venture in between these beasts which stood like towers of defence, the true strength of the Indian army. The only method was to begin by a cavalry attack on the flank; and Seleucus and the other captains of the infantry were bidden not to advance until they saw that both the horse and the foot of the foe were tumbled into confusion by the flank assault. Alexander determined to concentrate his attack on the left wing; perhaps because it was on the river side, and he would be within easier reach of his troops on the other bank. Accordingly he kept all his cavalry on his right wing. One body was entrusted to Coenus, who bore well to the right, and was ready to strike in the rear, and to deal with the body of horse stationed upon the enemy's right wing, in case they should come round to assist their comrades on the left. The mounted Scythian archers rode straight against the front of the enemy's cavalry -- which was still in column formation, not having had time to open out -- and harassed it with showers of arrows; while Alexander himself, with the rest of the heavy cavalry, led the charge upon the flank. Porus who had committed the fatal mistake of allowing the enemy to take the offensive -- brought up his remaining squadrons from the right wing as fast as he could. Then Coenus, who had ridden round close to the river-bank, fell upon them in the rear. The Indians had now to form a double front against the double foe. Alexander seized the moment to press hard upon the adverse squadrons; they swayed backwards and sought shelter behind the elephants. Then those elephant riders who were on this side of the army drove the beasts against the Macedonian horses; and at the same time the Macedonian footmen rushed forward and attacked the animals which were now turned sidewards towards them. But the other elephants of the line were driven into the ranks of the hypaspists, and dealt destruction, trampling down and striking furiously.

Heartened by the success of the elephants, the Indian cavalry rallied and charged, but beaten back by the Macedonian horse, who were now formed in a serried mass, they again sought shelter behind the elephantine wall. But many of the beasts were now-furious with wounds and beyond control; some had lost their riders; and in the mellay they trampled on friends and foes alike. The Indians suffered most, for they were surrounded and confined to the space in which the animals raged; while the Macedonians could attack the animals on side or rear, and then retreat into the open when they turned to charge. At length, when the elephants grew weary and their charges were feebler, Alexander closed in. He gave the order for the hypaspists to advance in close array shield to shield, while he, reforming his squadrons, dashed in from the side.

The enemy's cavalry, already weakened and dislocated, could not withstand the double shock and was cut to pieces. The hypaspists rolled in upon the enemy's infantry, who soon broke and fled. Meanwhile the generals on the other side of the river, Craterus and the rest, discovering that fortune was declaring for Alexander, crossed the river without resistance. Porus, who had shown himself a mediocre general but a most valiant soldier, when he saw most of his forces scattered, his elephants lying dead or straying riderless, did not flee -- as Darius had twice fled -- but remained fighting, seated on an elephant of commanding height, until he was wounded in the right shoulder, the only part of his body unprotected by mail. Then he turned round and rode away.

Alexander, struck with admiration at his prowess, sent messengers who overtook him and induced him to return. The victor, riding out to meet the old prince, was impressed by his stature and beauty, and asked him how he would fain be treated. "Treat me like a king," said Porus. "For my own sake," said Alexander, "I will do that; ask a boon for thy sake." "That," replied Porus, "containeth all."

And Alexander treated his captive royally. He not only gave him back his kingdom, but largely increased its borders. This royal treatment was inspired by deep policy. He could rest the security of his rule beyond the Indus on no better base than the mutual jealousy of two moderately powerful princes. He had made the lord of Taxila as powerful as was safe; the reinstatement of his rival Porus would be the best guarantee for his loyalty. But on either side of the Hydaspes, close to the scene of the battle, two cities were founded, which would serve as garrisons in the subject land. On the right hand, the city of Bucephala, named after Alexander's steed, which died here -- probably shortly before the battle -- of old age and weariness; on the left, Nicaea, the city of victory.

Leaving Craterus to build the cities, Alexander crossed the Acesines, more than a mile and a half broad, into the territory of a namesake and nephew of Porus, who fled eastward. Alexander left Hephaestion to march southward and subdue the land of the younger Porus, as well as the free communities between the two rivers. The news that the Cathaeans, a free and warlike people, were determined to give him battle, diverted Alexander from the pursuit. He stormed their chief town Sangala, and all their land was likewise placed under the lordship of Porus. Thus of the four river-bounded tracts which compose the Punjab, the largest, between Indus and Jehlum, belonged to Omphis of Taxila, while the three others, between Jehlum and Beas, were assigned to Porus.

Alexander now advanced to the Hyphasis, or Beas, and reached it higher up than the point where it joins the Sutlej. It was destined to be the landmark of his utmost march. He wished to go farther and explore the lands of the Ganges, but an unlooked-for obstacle occurred. The Macedonians were worn out with years of hard campaigning, and weary of this endless rolling on into the unknown. Their numbers had dwindled; the remnant of them were battered and grown old before their time. All yearned back to their homeland in the west.

On the banks of the Hyphasis the crisis came; the men resolved to go no farther. At a meeting of the officers which Alexander summoned, Coenus was the spokesman of the general feeling.

The king retired to his tent, and for two days refused to see any of his Companions, hoping that their hearts would be softened. But the Macedonians did not relent or go back from their purpose. On the third day, Alexander offered sacrifices preliminary to crossing the river, declaring that he would advance himself; but the victims gave unfavourable signs. Then the king yielded. When his will was made known, the way-worn veterans burst into wild joy; the more part of them shed tears. They crowded round the royal tent, blessing the unconquered king, that he had permitted himself to be conquered for once, by his Macedonians.

On the banks of the Hyphasis Alexander erected twelve towering altars to the twelve great gods of Olympus, as a thankoffering for having led him safely within reach of the world's end. For in Alexander's conception the Ganges discharged its waters into the ocean which bounded the earth on the east, as the Atlantic bounded it on the west of the world.

Alexander is often represented as

a madman, impelled by an insatiable lust of conquest for conquest's sake. But if the form and feature of the earth were what he pictured it to be, twenty years would have sufficed to make his empire conterminous with its limits. He might have ruled from the eastern to the western ocean, from the ultimate bounds of Scythia to the shores of Libya; he might have brought to pass in the three continents an universal peace, and dotted the habitable globe with his Greek cities. The advance to the Indus was no mere wanton aggression, but was necessary to establish secure routes for trade with India, which was at the mercy of the wild hill-tribes; and the subjugation of the Punjab was a necessity for securing the Indus frontier.

The solid interests of commerce underlay the ambitions of the Macedonian conqueror. Alexander retraced his steps to the Hydaspes, on his way picking up Hephaestion, who had founded a new city on the banks of the Acesines. On the Hydaspes, Craterus had not only built the two cities at the scene of the great battle, but had also prepared a large fleet of transports, which was to carry part of the army down the river to reach the Indus and the ocean. The fleet was placed under the command of Nearchus; the rest of the army, divided into two parts, marched along either bank, under Hephaestion and Craterus.

As they advanced, the only formidable resistance that they encountered was from the free and warlike tribe of the Malli. Having routed a large host of these Indians, Alexander pursued them to their chief city, which is possibly to be sought near the site of the modern Multan. Here he met with a grave adventure. The city had been easily taken, and the Indians had retreated into the citadel. Two ladders were brought to scale the earthen wall, but it was found hard to place them beneath the shower of missiles from above.

Impatient at the delay, Alexander seized a ladder and climbed up under the cover of a shield. Peucestas, who bore the sacred buckler from the temple of Ilion, and Leonnatus followed, and Abreas ascended the other ladder. When the king reached the battlement, he hurled down or slew the Indians who were posted at that spot.

The hypaspists, when they saw their king standing upon the wall, a mark for the whole garrison of the fortress, made a rush for the ladders, and both ladders broke under the weight of the crowd. Only those three -- Peucestas, Leonnatus, and Abreas -- reached the wall before the ladders broke. His friends implored Alexander to leap down; he answered their cries by leaping down among the enemy. He alighted on his feet. With his back to the wall he stood alone against the throng of foes, who recognised the Great King. With his sword he cut down their leader and some others who ventured to rush at him; he felled two more with stones; and the rest, not daring to approach, pelted him with missiles. Meanwhile his three companions had cleared the wall of its defenders and leapt down to help their king.

Abreas fell slain by a dart. Then Alexander himself received a wound in the breast. For a space he stood and fought, but at last sank on his shield fainting through loss of blood. Peucestas stood over him with the holy shield of Troy, Leonnatus guarded him on the other side, until rescue came.

Having no ladders, the Macedonians had driven pegs into the wall, and a few had clambered up as best they could and flung themselves down into the fray. Some of these succeeded in opening one of the gates, and then the fort was taken. No man, woman, or child in the place was spared by the infuriated soldiers, who thought that their king was dead. But, though the wound was grave, Alexander recovered. The rumour of his death reached the camp where the main army was waiting at the junction of the Ravee with the Chenab, and it produced deep consternation and despair. Reassuring letters were not believed; so Alexander caused himself to be carried to the banks of the Ravee and conveyed by water down to the camp. When he drew near, the canopy which sheltered his bed in the stern of the vessel was removed. The soldiers, still doubting, thought it was his corpse they saw, until the barque drew close to the bank and he waved his hand. Then the host shouted for joy. When he was carried ashore, he was lifted for a moment on horseback, that he might be the better seen of all; and then he walked a few steps for their greater reassurance.

This adventure is an extreme case of Alexander's besetting weakness, which has been illustrated in many other of his actions. In the excitement of battle, amid the ring of arms, he was apt to forget his duties as a leader. To have endangered his own safety was a crime against the whole army.

The Malli made a complete submission; and when Alexander had recovered from his wound, the fleet sailed downward, and the Indian tribes submitted, presenting to the conqueror the characteristic products of India -- gems, fine draperies, tame lions and tigers. At the place where the united stream of the four lesser rivers joins the mighty flow of the Indus, the foundations were laid of a new Alexandria. The next stage of the southward advance was the capital town of the Sogdi, which lay upon the river. Alexander refounded it as a Greek colony, and built wharfs; it was known as the Sogdian Alexandria, and was destined to be the residence of a southern satrapy which was to extend to the sea-coast. It is impossible to identify the sites of these cities, because the face of the Punjab has completely changed, through the alteration of the courses of its rivers, since the days of Alexander.

Fig. 93: Coin of Alexander. Obverse: head of Heracles, in lion's skin. Reverse: eagle-bearing Zeus, and prow of galley in field [legend: [x]].

Fig. 93: Coin of Alexander. Obverse: head of Heracles, in lion's skin. Reverse: eagle-bearing Zeus, and prow of galley in field [legend: [x]].The principalities of the rich and populous land of Sind were distinguished from the states of the north by the great political power enjoyed by the Brahmans. Under the influence of this caste, the princes either defied Alexander or, if they submitted at first, speedily rebelled. Thus it was nearly midsummer when the king reached Patala, near the Indian Ocean.

On the tidings of an insurrection in Arachosia, he had dispatched Craterus with a considerable portion of the army to march through the Bolan Pass into southern Afghanistan and put down the revolt. Alexander himself designed to march through Baluchistan, and Craterus was ordered to meet him in Kirman, near the entrance of the Persian Gulf. Another division of the host was to go by sea to the mouth of the Tigris.

The king fixed upon Patala to be for the Indian empire what the most famous of his Alexandrias was for Egypt. He charged Hephaestion with the task of fortifying the citadel and building an ample harbour.

Regio Patalis is Latin for “the region of Patala”, that is the region around the ancient city of Patala at the mouth of the Indus River in Sindh, Pakistan. The historians of Alexander the Great state that the Indus parted into two branches at the city of Patala before reaching the sea, and the island thus formed was called Patalene, the district of Patala. Alexander constructed a harbour at Patala.

While the Patala was well known to mariners and traders of the Ancient Mediterranean, by the European Middle Ages, mapmakers no longer knew its location. Regio Patalis appeared on late 15th and early 16th century maps and globes in a variety of increasingly erroneous locations, further and further east and south of India. It even appeared on some maps as a promontory of Terra Australis...

Ahmad Hasan Dani, director of the Taxila Institute of Asian Civilisations, Islamabad, concluded: “There has been a vain attempt to identify the city of Patala. If ‘Patala’ is not taken as a proper name but only refers to a city, it can be corrected to ‘Pattana’, that is, [Sanskrit for] a city or port city par excellence, a term applied in a later period to Thatta [onetime capital of Sindh], which is ideally situated in the way the Greek historians describe”.

-- Regio Patalis, by Wikipedia

Then he sailed southward himself to visit the southern ocean. He sacrificed to Poseidon; he poured drink-offerings from a golden cup to the Nereids and Dioscuri, and to Thetis the mother of his ancestor Achilles, and then hurled the cup into the waves. This ceremony inaugurated his plan of opening a seaway for commerce between the West and the Far East. The enterprise of discovering this seaway was entrusted to Nearchus. Alexander started on his land-march in the early autumn, but Nearchus and the fleet were to wait till October, in order to be helped forward by the eastern monsoons.

SECT. 3. Alexander's Return to Babylon. No enterprise of Alexander was so useless, and none so fatal, as the journey through the desert of Gedrosia, the land which is now known as the Mekran. His guiding motive in choosing this route was to make provisions for the safety of the fleet, to dig wells and store food at certain places along the coast. The march through the Mekran and the voyage of Nearchus were interdependent parts of the same adventure; and so timid were the mariners of those days that the voyage into unknown waters seemed far more formidable than the journey through the waste.

Aug.- Oct., 325 B.C.With perhaps thirty thousand men,

Alexander passed the mountain wall which protects the Indus delta, and reduced the Oritae to subjection before he descended into the waste of Gedrosia. The army moved painfully through the desert, where it was often almost impossible to step through the deep sinking sand. Alexander himself is said to have trudged on foot and shared all the hardships of the way. At length the waste was crossed; the losses of that terrible Gedrosian journey exceeded the losses of all Alexander's campaigns.

Having rested at Pura,

the king proceeded to Kirman, where he was joined by Craterus, who had suppressed the revolt in Arachosia. Presently news arrived that the fleet had reached the Kirman coast, and soon Nearchus arrived at the camp and relieved Alexander's anxiety. They had been weather-bound and had lost three ships; but the king was overjoyed that they had arrived at all. Nearchus was dismissed to complete the voyage by sailing up the Persian Gulf and the Pasitigris River to Susa; Hephaestion was sent to make his way thither along the coast; while Alexander himself marched through the hills by Persepolis and Pasargadae.

It was high time for Alexander to return. There was hardly a satrap, Persian or Macedonian, in any land, who had not oppressed his province by violence and rapacity. Many satraps were deposed or put to death; and one guilty minister fled at Alexander's approach. This was the treasurer Harpalus, who had squandered his master's money in riotous living at Babylon, and deemed it prudent to move westward. Taking a large sum of money, he went to Cilicia, and hiring a bodyguard of 6000 mercenaries, he lived in royal state at Tarsus. On Alexander's return he fled to Greece, where we shall meet him presently.

Having punished with a stern hand the misrule of his satraps, Macedonian and Persian alike, Alexander began to carry out schemes which he had formed. He had unbarred and unveiled the Orient to the knowledge and commerce of the Mediterranean peoples, but

his aim was to do much more than this; it was no less than to fuse Asia and Europe into a homogeneous unity. He devised various means for compassing this object. He proposed to transplant Greeks and Macedonians into Asia, and Asiatics into Europe, as permanent settlers. This plan had indeed been partly realised by the foundation of his numerous mixed cities in the Far East. The second means was the promotion of intermarriages between Persians and Macedonians, and this policy was inaugurated in magnificent fashion at Susa. The king himself espoused Statira, the daughter of Darius; his friend Hephaestion took her sister; and a large number of Macedonian officers wedded the daughters of Persian grandees. Of the general mass of the Macedonians 10,000 are said to have followed the example of their officers and taken Asiatic wives; all those were liberally rewarded by Alexander. It is to be noticed that

Alexander, already wedded to the princess of Sogdiana, adopted the polygamous custom of Persia; and he even married another royal lady, Parysatis, daughter of Ochus. These marriages were purely dictated by policy; for Alexander never came under the influence of women. But the most effective means for bringing the two races together was the institution of military service on a perfect equality. With this purpose in view,

Alexander, not long after the death of Darius, had arranged that in all the eastern provinces the native youth should be drilled and disciplined in Macedonian fashion and taught to use the Macedonian weapons. In fact, Hellenic military schools were established in every province, and at the end of five years an army of 30,000 Hellenized barbarians was at the Great King's disposition. At his summons this army gathered at Susa, and its arrival created a natural, though unreasonable, feeling of discontent among the Macedonians, who divined that Alexander aimed at making himself independent of their services. His schemes of transforming the character of his army were also indicated by the enlistment of Persians and other Orientals in the Macedonian cavalry regiments.

324 B.C. Alexander left Susa for Ecbatana in spring. He sailed down the river Pasitigris to the Persian Gulf, surveyed part of the coast, and sailed up the Tigris, removing the weirs which the Persians had constructed to hinder navigation.

The army joined him on the way, and he halted at Opis. Here he held an assembly of the Macedonians, and formally discharged all those -- about 10,000 in number -- whom old age or wounds had rendered unfit for warfare, promising to make them comfortable for life. The smouldering discontent found a voice now. The cry was raised, "Discharge us all." Alexander leapt down from the platform into the shouting throng; he pointed out thirteen of the most forward rioters, and bade his hypaspists seize them and put them to death. The rest were cowed. Amid a deep silence the king remounted the platform, and in a bitter speech he discharged the whole army. Then he retired into his palace, and on the third day summoned the Persian and Median nobles and appointed them to posts of honour and trust which had hitherto been filled by Macedonians. The names of the Macedonian regiments were transferred to the new barbarian army. When they heard this, the Macedonians, who still lingered in their quarters, miserable and uncertain whether to go or stay, appeared before the gates of the palace. They laid down their arms submissively and implored admission to the king's presence. Alexander came out, and there was a tearful reconciliation, which was sealed by sacrifices and feasts. The summer and early winter were spent at the Median capital. Here a sorrow, the greatest that could befall him, befell Alexander. Hephaestion fell ill, languished for seven days, and died. Alexander fasted three days, and the whole empire went into mourning.

Alexander set out for Babylon towards the end of the year, and on his way

ambassadors from far lands came to his camp. The Bruttians, Lucanians, and Etruscans, the Carthaginians and the Phoenician colonies of Spain, Celts, Scythians of the Black Sea, Libyans, and Ethiopians had all sent envoys to court the friendship of the monarch who seemed already to be lord of half the earth. SECT. 4. Preparations for an Arabian Expedition. Alexander's Death. Ever since the successful voyage of Nearchus, Alexander was bent on the circumnavigation and conquest of Arabia. His eastern empire was not complete so long as this peninsula lay outside it. The possession of this country of sand, however, was only an incident in the grand range of his plans. His visit to India and the voyage of Nearchus had given him new ideas; he had risen to the conception of making the southern ocean another great commercial sea like the Mediterranean. He hoped to establish a regular trade-route from the Indus to the Tigris and Euphrates, and thence to the canals which connected the Nile with the Red Sea. Alexander destined Babylon to be the capital of his empire, and doubtless it was a wise choice. But its character was now to be transformed. It was to become a naval station and a centre of maritime commerce. Alexander set about the digging of a great harbour, with room for a thousand keels.

323 B.C.All was in readiness at length for the expedition to the south. On a day in early June a royal banquet was given in honour of Nearchus and his seamen, shortly about to start on their oceanic voyage. Two nights of carousal ended in a fever which held him for six days, while the expedition's departure was postponed for another and yet another day. Then his condition grew worse, and he was carried back to the palace, where he won a little sleep, but the fever did not abate. When his officers came to him they found him speechless; the disease became more violent, and a rumour spread among the Macedonian soldiers that Alexander was dead. They rushed clamouring to the door of the palace, and the bodyguards were forced to admit them. One by one they filed past the bed of their young king, but he could not speak to them; he could only greet each by slightly raising his head and signing with his eyes. Peucestas and some others of the Companions passed the night in the temple of Serapis and asked the god whether they should convey the sick man into the temple, if haply he might be cured there by divine help. A voice warned them not to bring him, but to let him remain where he lay.

He died on a June evening, before the thirty-third year of his age was fully told.

His sudden death was no freak of fate or fortune; it was a natural consequence of his character and his deeds. Into thirteen years he had compressed the energies of many lifetimes. Sparing of himself neither in battle nor at the symposion, he was doomed to die young.

SECT. 5. Greece under Macedonia. 331 B.C.The tide of the world's history swept us away from the shores of Greece; we could not pause to see what was happening in the little states which were looking with mixed emotions at the spectacle of their own civilisation making its way over the earth. Alexander's victory at the gates of Issus and his ensuing supremacy by sea had taught many of the Greeks the lesson of caution; the Confederacy of the Isthmus had sent congratulations and a golden crown to the conqueror; and when, a twelvemonth later, the Spartan king Agis renewed the war against Macedonia, he got no help or countenance outside the Peloponnesus. Agis induced the Arcadians, except Megalopolis, the Achaeans, and the Eleians, to join him; and the chief object of the allies was to capture Megalopolis. Antipater, as soon as the situation in Thrace set him free, marched 531 B.C. southward to the relief of Megalopolis, and easily crushed the allies in a battle fought hard by Agis fell fighting, and there was no further resistance.

So long as Darius lived, many of the Greeks cherished secret hopes that fortune might yet turn. But on the news of his death such hopes expired, and it was not till Alexander's return from India that anything happened to trouble the peace.

330 B.C. For Athens the twelve years between the fall of Thebes and the death of Alexander were an interval of singular well-being. The conduct of public affairs was in the hands of the two most honourable statesmen of the day, Phocion and Lycurgus; and Demosthenes was sufficiently clear-sighted not to embarrass, but, when needful, to support, the policy of peace. Phocion probably did not grudge him the signal triumph which he won over his old rival, Aeschines; for this triumph had only a personal, and not a political, significance. Ctesiphon had proposed to honour Demosthenes, both for his general services to the state and especially for his liberality in contributing from his private purse towards the repair of the city-walls, by crowning him publicly in the theatre with a crown of gold. The Council passed a resolution to this effect; but Aeschines lodged an accusation against the proposer, on the ground that the motion violated the Graphe Paranomon. In a speech of the highest ability Aeschines reviewed the public career of Demosthenes, to prove that he was a traitor and responsible for all the disasters of Athens. The reply of Demosthenes, a masterpiece of splendid oratory, captivated the judges; and Aeschines, not winning one-fifth part of their votes, left Athens and disappeared from politics.

The Macedonian empire had not yet lasted long enough to turn the traffic of the Mediterranean into new channels, and Athens still enjoyed great commercial prosperity. Although peace was her professed policy, she did not neglect to make provision, in case opportunity should come round, for regaining her sovereignty on sea. Money was spent on the navy, which is said to have been increased to well-nigh 400 galleys, and on new ship-sheds. The man who was mainly responsible for this naval expenditure was Lycurgus. In recent years considerable changes had been made in the constitution of the financial offices. Eubulus had administered as the president of the Theoric Fund. But now we find the control of the expenditure in the hands of a Minister of the Public Revenue, who was elected by the people and held office for four years, from one Panathenaic festival to another. Lycurgus held this post. The post practically included the functions of a minister of public works, and the ministry of Lycurgus was distinguished by building enterprises. He constructed the Panathenaic stadion on the southern bank of the Ilisus. He rebuilt the Lycean gymnasium, where in these years the philosopher Aristotle used to take his morning and evening "walks," teaching his "peripatetic" disciples. But the most memorable work of Lycurgus was the reconstruction of the theatre of Dionysus. It was he who built the rows of marble benches, climbing up the steep side of the Acropolis, as we see them to-day.

Thus Athens discreetly attended to her material well-being, and courted the favour of the gods, and the only distress which befell her was a dearth of corn.

But on the return of Alexander to Susa, two things happened which imperilled the tranquillity of Greece. Alexander promised the Greek exiles -- there were more than 20,000 -- of them to procure their return to their native cities. 324 B.C. He sent Nicanor to the great congregation of Hellas at the Olympian festival, to order the states to receive back their banished citizens. Only two states objected -- Athens and Aetolia; and they objected because, if the edict were enforced, they would be robbed of ill-gotten gains. The Aetolians had possessed themselves of Oeniadae and driven out its Acarnanian owners. The position of Athens in Samos was similar; the Samians would now be restored to their own lands, and the Athenian settlers would have to go. Both Athens and Aetolia were prepared to resist. SECT. 6. The Episode of Harpalus and the Greek Revolt. Meanwhile an incident had happened which might induce some of the patriots to hope that Alexander's empire rested on slippery foundations. Harpalus had arrived off the coast of Attica with 5000 talents, a body of mercenaries, and thirty ships. He had come to excite a revolt against his master. Refused admission with his force, he came alone to Athens with a sum of about 700 talents. After a while messages arrived both from Macedonia and from Philoxenus, Alexander's financial minister in western Asia, demanding his surrender. The Athenians, on the proposal of Demosthenes, adopted a clever device. They arrested Harpalus, seizing his treasure, and said that they would surrender him to officers expressly sent by Alexander, but declined to give him up to Philoxenus or Antipater. Harpalus escaped, and was shortly afterwards murdered by one of his fellow- adventurers.

The stolen money was deposited in the Acropolis, under the charge of specially-appointed commissioners, of whom Demosthenes was one. Suddenly it was discovered that only 35 talents were actually in the Acropolis. Charges immediately circulated against the influential politicians, that the other 350 talents had been received in bribes by them before the money was deposited in the citadel. The court of Areopagus satisfied themselves that a number of leading statesmen had received considerable sums. Demosthenes appeared in their report as the recipient of twenty talents. He confessed the misdemeanor himself, and sought to excuse it by the subterfuge that he had taken it to repay himself for twenty talents which he had advanced to the Theoric Fund. But why should he repay himself, without any authorisation, out of Alexander's money, for a debt owed him by the Athenian state? The charges against Demosthenes were twofold: he had taken money, and he had culpably omitted to report the amount of the deposit and the neglect of those who were set to guard it. He was condemned to pay a fine of fifty talents. Unable to pay it, he was imprisoned, but presently effected his escape.

323 B.C.-322 B.C.If Alexander had lived, the Athenians might have persuaded him to let them remain in occupation of Samos; for he was always disposed to be lenient to Athens.

When the tidings of his death came, men almost refused to credit it; the orator Demades forcibly said, "If he were indeed dead, the whole world would have smelt of his corpse.'' It did not seem rash to strike for freedom in the unsettled condition of things after his death.

Athens revolted from Macedonia; she was joined by Aetolia and many states in northern Greece, and she secured the services of a band of 8000 discharged mercenaries who had just returned from Alexander's army. One of their captains, the Athenian, Leosthenes, occupied Thermopylae, and near that pass the united Greeks gained a slight advantage over Antipater, who had marched southward as soon as he could gather his troops together. No state in north Greece except Boeotia remained true to Macedonia. The regent shut himself in the strong hill-city of Lamia, which stands over against the pass of Thermopylae under a spur of Othrys; and here he was besieged during the winter by Leosthenes. These successes had gained some adherents to the cause in the Peloponnesus; and, if the Greeks had been stronger at sea, that cause might have triumphed, at least for a while. In spring the arrival of Leonnatus, governor of Hellespontine Phrygia, at the head of an army, raised the siege of Lamia.

The Greeks marched into Thessaly to meet the new army before it united with Antipater; a battle was fought, in which Leonnatus was wounded to death. Antipater arrived the next day, and, joining forces with the defeated army, withdrew into Macedonia, to await Craterus, who was approaching from the east. When Craterus arrived, they entered Thessaly together, and in an engagement at Crannon, in which the losses on both sides were light, the Macedonians had a slight advantage. This battle apparently decided the war, but the true cause which hindered the Greeks from continuing the struggle was not the insignificant defeat at Crannon, but the want of unity among themselves, the want of a leader whom they entirely trusted. They were forced to make terms singly, each state on its own behoof.

Athens submitted when Antipater advanced into Boeotia and prepared to invade Attica. She paid dearly for her attempt to win back her power. Antipater like Alexander had no soft place in his heart for the memories and traditions of Athens. He saw only that, unless strong and stern measures were taken, Macedonia would not be safe against a repetition of the rising which he had suppressed. He therefore imposed three conditions, which Phocion and Demades were obliged to accept: that the democratic constitution should be modified by a property qualification; that a Macedonian garrison should be lodged in Munychia; and that the agitators, Demosthenes, Hypereides, and their friends, should be surrendered. Oct. 322 B.C. Demosthenes had exerted eloquence in gaining support for the cause of the allies in the Peloponnesus, and his efforts had been rewarded by his recall to Athens. As soon as the city had submitted, he and the other orators fled.

Hypereides with two companions sought refuge in the temple of Aeacus at Aegina, whence they were taken to Antipater and put to death. Demosthenes fled to the temple of Poseidon in the island of Calaurea. When the messengers of Antipater appeared and summoned him forth, he swallowed poison, which he had concealed, according to one story, in a pen, and was thus delivered from falling into the hands of the executioner.