Seleucus I Nicator

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/22/21

Delu is said to have been a prince of uncommon bravery and generosity; benevolent towards men, and devoted to the service of God. The most remarkable transaction of his reign is the building of the city of Delhi, which derives its name from its founder, Delu. In the fortieth year of his reign, Phoor, a prince of his own family, who was governor of Cumaoon, rebelled against the Emperor, and marched to Kinoge, the capital. Delu was defeated, taken, and confined in the impregnable fort of Rhotas.

Phoor immediately mounted the throne of India, reduced Bengal, extended his power from sea to sea, and restored the empire to its pristine dignity. He died after a long reign, and left the kingdom to his son, who was also called Phoor, and was the same with the famous Porus, who fought against Alexander.

The second Phoor [Porus], taking advantage of the disturbances in Persia, occasioned by the Greek invasion of that empire under Alexander, neglected to remit the customary tribute, which drew upon him the arms of that conqueror. The approach of Alexander did not intimidate Phoor [Porus]. He, with a numerous army, met him at Sirhind, about one hundred and sixty miles to the north-west of Delhi, and in a furious battle, say the Indian historians, lost many thousands of his subjects, the victory, and his life. The most powerful prince of the Decan, who paid an unwilling homage to Phoor, or Porus, hearing of that monarch's overthrow, submitted himself to Alexander, and sent him rich presents by his son. Soon after, upon a mutiny arising in the Macedonian army, Alexander returned by the way of Persia.

Sinsarchund, the same whom the Greeks call Sandrocottus, assumed the imperial dignity after the death of Phoor, and in a short time regulated the discomposed concerns of the empire. He neglected not, in the mean time, to remit the customary tribute to the Grecian captains, who possessed Persia under, and after the death of, Alexander. Sinsarchund, and his son after him, possessed the empire of India seventy years.

-- History of Hindostan; From the Earliest Account of Time, To the Death of Akbar; Translated From the Persian of Mahummud Casim Ferishta of Delhi: Together With a Dissertation Concerning the Religion and Philosophy of the Brahmins; With an Appendix, Containing the History of the Mogul Empire, From Its Decline in the Reign of Mahummud Shaw, to the Present Times,(1768), by Alexander Dow.

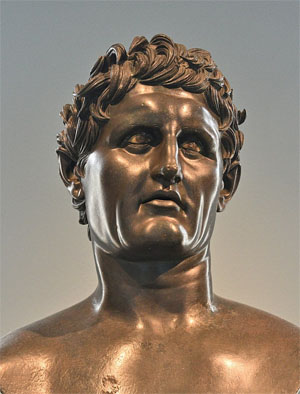

Seleucus I Nicator

A Roman copy of a Greek statue of Seleucus I found in Herculaneum. Now located at the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

Basileus of the Seleucid Empire

Reign: 305[1] – September 281 BC

Successor: Antiochus I Soter

Co-king: Antiochus I Soter (~292-281 BC)

Born: c. 358 BC, Europos, Macedon

Died: September 281 BC (aged c. 77), Thrace

Spouse: Apama of Sogdiana; Stratonice of Syria

Issue: Apama; Antiochus I Soter; Achaeus; Phila; Helena

Dynasty: Seleucid dynasty

Father: Antiochus

Mother: Laodice

Religion: Greek polytheism

Seleucus I portrait on Antiochus I tetradrachm

Seleucus I Nicator (/səˈljuːkəs naɪˈkeɪtər/; c. 358 BC – September 281 BC; Ancient Greek: Σέλευκος Νικάτωρ, romanized: Séleukos Nikátōr, lit. 'Seleucus the Victor') was a Greek general and one of the Diadochi, the rival generals, relatives, and friends of Alexander the Great who fought for control over his empire after his death.[A] Having previously served as an infantry general under Alexander the Great, he eventually assumed the title of basileus (king) and established the Seleucid Empire, one of the major powers of the Hellenistic world, which controlled most of Asia Minor, Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Iranian Plateau until overcome by the Roman Republic and Parthian Empire in the late second and early first centuries BC.

After the death of Alexander in June 323 BC, Seleucus initially supported Perdiccas, the regent of Alexander's empire, and was appointed Commander of the Companions and chiliarch at the Partition of Babylon in 323 BC. However, after the outbreak of the Wars of the Diadochi in 322, Perdiccas' military failures against Ptolemy in Egypt led to the mutiny of his troops in Pelusium. Perdiccas was betrayed and assassinated in a conspiracy by Seleucus, Peithon and Antigenes in Pelusium sometime in either 321 or 320 BC. At the Partition of Triparadisus in 321 BC, Seleucus was appointed Satrap of Babylon under the new regent Antipater. But almost immediately, the wars between the Diadochi resumed and one of the most powerful of the Diadochi, Antigonus, forced Seleucus to flee Babylon. Seleucus was only able to return to Babylon in 312 BC with the support of Ptolemy. From 312 BC, Seleucus ruthlessly expanded his dominions and eventually conquered the Persian and Median lands. Seleucus ruled not only Babylonia, but the entire enormous eastern part of Alexander's empire.

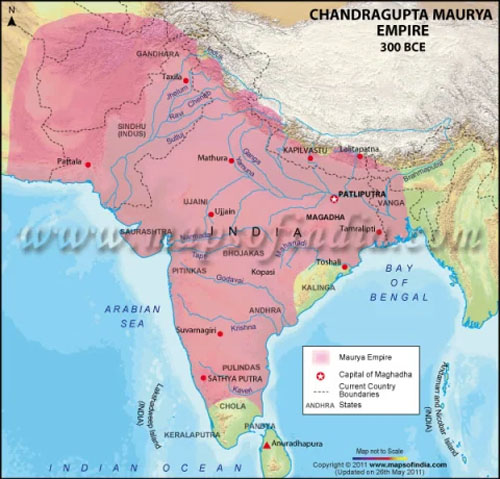

Seleucus further made claim to the former satraps in Gandhara and in eastern India. However these ambitions were contested by Chandragupta Maurya[??], resulting in the Seleucid–Mauryan War (305–303 BC). The conflict was ultimately resolved by a treaty[??] resulting in the Maurya Empire annexing the eastern satraps. Additionally, a marriage alliance between the two empires was formalized with Chandragupta[??] marrying Seleucus' daughter. Furthermore, the Seleucid Empire received a considerable military force of 500 war elephants with mahouts, which would play a decisive role against Antigonus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BC. In 281 BC, he also defeated Lysimachus at the Battle of Corupedium, adding Asia Minor to his empire.

Seleucus' victories against Antigonus and Lysimachus left the Seleucid dynasty virtually unopposed amongst the Diadochi. However, Seleucus also hoped to take control of Lysimachus' European territories, primarily Thrace and Macedon itself. But upon arriving in Thrace in 281 BC, Seleucus was assassinated by Ptolemy Ceraunus,[2] who had taken refuge at the Seleucid court with his sister Lysandra. The assassination of Seleucus destroyed Seleucid prospects in Thrace and Macedon, and paved the way for Ptolemy Ceraunus to absorb much of Lysimachus' former power in Macedon. Seleucus was succeeded by his son Antiochus I as ruler of the Seleucid Empire.

Seleucus founded a number of new cities during his reign, including Antioch (300 BC) and Seleucia on the Tigris (c. 305 BC), a foundation that eventually depopulated Babylon.

Youth and family

Seleucus was the son of Antiochus. Historian Junianus Justinus claims that Antiochus was one of Philip II of Macedon's generals, but no such general is mentioned in any other sources, and nothing is known of his supposed career under Philip. It is possible that Antiochus was a member of an upper Macedonian noble family. Seleucus' mother was supposedly called Laodice, but nothing else is known of her. Later, Seleucus named a number of cities after his parents.[3] Seleucus was born in Europos, located in the northern part of Macedonia. Just a year before his birth (if the year 358 BC is accepted as the most likely date), the Paeonians invaded the region. Philip defeated the invaders and only a few years later utterly subdued them under Macedonian rule.[4] Seleucus' year of birth is unclear. Justin claims he was 77 years old during the battle of Corupedium, which would place his year of birth at 358 BC. Appianus tells us Seleucus was 73 years old during the battle, which means 354 BC would be the year of birth. Eusebius of Caesarea, however, mentions the age of 75, and thus the year 356 BC, making Seleucus the same age as Alexander the Great. This is most likely propaganda on Seleucus' part to make him seem comparable to Alexander.[5]

As a teenager, Seleucus was chosen to serve as the king's page (paides). It was customary for all male offspring of noble families to first serve in this position and later as officers in the king's army.[3]

A number of legends, similar to those told of Alexander the Great, were told of Seleucus. It was said Antiochus told his son before he left to battle the Persians with Alexander that his real father was actually the god Apollo. The god had left a ring with a picture of an anchor as a gift to Laodice. Seleucus had a birthmark shaped like an anchor. It was told that Seleucus' sons and grandsons also had similar birthmarks. The story is similar to the one told about Alexander. Most likely the story is merely propaganda by Seleucus, who presumably invented the story to present himself as the natural successor of Alexander.[3]

John Malalas tells us Seleucus had a sister called Didymeia, who had sons called Nicanor and Nicomedes. It is most likely the sons are fictitious. Didymeia might refer to the oracle of Apollo in Didyma near Miletus. It has also been suggested that Ptolemy (son of Seleucus) was actually the uncle of Seleucus.[6]

Early career under Alexander the Great

Seleucus led the Royal Hypaspistai during Alexander's Persian campaign.

In spring 334 BC, as a young man of about twenty-three, Seleucus accompanied Alexander into Asia.[2] By the time of the Indian campaigns beginning in late in 327 BC, he had risen to the command of the élite infantry corps in the Macedonian army, the "Shield-bearers" (Hypaspistai, later known as the "Silvershields"). It is said by Arrian that when Alexander crossed the Hydaspes river on a boat, he was accompanied by Perdiccas, Ptolemy I Soter, Lysimachus and also Seleucus.[7] During the subsequent Battle of the Hydaspes (326 BC), Seleucus led his troops against the elephants of King Porus. It is unknown the extent in which Seleucus participated in the actual planning of the battle, as he is not mentioned as holding any major independent position during the battle. This contrasts Craterus, Hephaistion, Peithon and Leonnatus – each of whom had sizable detachments under his control.[8] Seleucus' Royal Hypaspistai were constantly under Alexander's eye and at his disposal. They later participated in the Indus Valley campaign, in the battles fought against the Malli and in the crossing of the Gedrosian desert.

At the great marriage ceremony at Susa in the spring of 324 BC, Seleucus married Apama (daughter of Spitamenes), and she bore him his eldest son and successor Antiochus I Soter, at least two legitimate daughters (Laodice and Apama) and possibly another son (Achaeus). At the same event, Alexander married the daughter of the late Persian King Darius III while several other Macedonians married Persian women. After Alexander's death (323 BC), when the other senior Macedonian officers unloaded their "Susa wives" en masse, Seleucus was one of the very few who kept his wife, and Apama remained his consort (later Queen) for the rest of her life.[9]

Ancient sources mention Seleucus three times before the death of Alexander. He participated in a sailing trip near Babylon, took part in the dinner party of Medeios the Thessalian with Alexander and visited the temple of the god Serapis.[citation needed] In the first of these episodes, Alexander's diadem was blown off his head and landed on some reeds near the tombs of Assyrian kings. Seleucus swam to fetch the diadem back, placing it on his own head while returning to the boat to keep it dry. The validity of the story is dubious. The story of the dinner party of Medeios may be true, but the plot to poison the King is unlikely.[clarification needed insufficient details and context] In the final story, Seleucus reportedly slept in the temple of Serapis in the hope that Alexander's health might improve. The validity of this story is also questionable, as the Graeco-Egyptian Serapis had not been invented at the time.[10]

Senior officer under Perdiccas (323–321 BC)

Ptolemy I Soter, an officer under Alexander the Great, was nominated as the satrap of Egypt. Ptolemy made Ptolemaic Egypt independent and proclaimed himself Basileus and Pharaoh in 305 BC.

Main article: Diadochi

Alexander the Great died without a successor in Babylon on June 10, 323 BC. His general Perdiccas became the regent of all of Alexander's empire, while Alexander's physically and mentally disabled half-brother Arrhidaeus was chosen as the next king under the name Philip III of Macedon. Alexander's unborn child (Alexander IV) was also named his father's successor. In the "Partition of Babylon" however, Perdiccas effectively divided the enormous Macedonian dominion among Alexander's generals. Seleucus was chosen to command the Companion cavalry (hetairoi) and appointed first or court chiliarch, which made him the senior officer in the Royal Army after the regent and commander-in-chief Perdiccas. Several other powerful men supported Perdiccas, including Ptolemy, Lysimachus, Peithon and Eumenes. Perdiccas' power depended on his ability to hold Alexander's enormous empire together, and on whether he could force the satraps to obey him.[10]

War soon broke out between Perdiccas and the other Diadochi. To cement his position, Perdiccas tried to marry Alexander's sister Cleopatra. The First War of the Diadochi began when Perdiccas sent Alexander's corpse to Macedonia for burial. Ptolemy however captured the body and took it to Alexandria. Perdiccas and his troops followed him to Egypt, whereupon Ptolemy conspired with the satrap of Media, Peithon, and the commander of the Argyraspides, Antigenes, both serving as officers under Perdiccas, and assassinated him. Cornelius Nepos mentions that Seleucus also took part in this conspiracy, but this is not certain.[11]

Satrap of Babylonia (321–316 BC)

Damaged Roman copy of a bust of Seleucus I, Louvre

The most powerful man in the empire after the death of Perdiccas was Antipater. Perdiccas' opponents gathered in Triparadisos, where the empire of Alexander was partitioned again (the Treaty of Triparadisus 321 BC).[12]

At Triparadisos the soldiers had become mutinous and were planning to murder their master Antipater. Seleucus and Antigonus, however, prevented this.[13] For betraying Perdiccas, Seleucus was awarded the rich province of Babylon. This decision may have been Antigonus' idea. Seleucus' Babylon was surrounded by Peucestas, the satrap of Persis; Antigenes, the new satrap of Susiana and Peithon of Media. Babylon was one of the wealthiest provinces of the empire, but its military power was insignificant. It is possible that Antipater divided the eastern provinces so that no single satrap could rise above the others in power.[12]

After the death of Alexander, Archon of Pella was chosen satrap of Babylon. Perdiccas, however, had plans to supersede Archon and nominate Docimus as his successor. During his invasion of Egypt, Perdiccas sent Docimus along with his detachments to Babylon. Archon waged war against him, but fell in battle. Thus, Docimus was not intending to give Babylon to Seleucus without a fight. It is not certain how Seleucus took Babylon from Docimus, but according to one Babylonian chronicle an important building was destroyed in the city during the summer or winter of 320 BC. Other Babylonian sources state that Seleucus arrived in Babylon in October or November 320 BC. Despite the presumed battle, Docimus was able to escape.

Meanwhile, the empire was once again in turmoil. Peithon, the satrap of Media, assassinated Philip, the satrap of Parthia, and replaced him with his brother Eudemus as the new satrap. In the west Antigonus and Eumenes waged war against each other. Just like Peithon and Seleucus, Eumenes was one of the former supporters of Perdiccas. Seleucus' biggest problem was, however, Babylon itself. The locals had rebelled against Archon and supported Docimus. The Babylonian priesthood had great influence over the region. Babylon also had a sizeable population of Macedonian and Greek veterans of Alexander's army. Seleucus won over the priests with monetary gifts and bribes.[14]

Second War of the Diadochi

Main article: Second War of the Diadochi

After the death of Antipater in 319 BC, the satrap of Media began to expand his power. Peithon assembled a large army of perhaps over 20,000 soldiers. Under the leadership of Peucestas the other satraps of the region brought together an opposing army of their own. Peithon was finally defeated in a battle waged in Parthia. He escaped to Media, but his opponents did not follow him and rather returned to Susiana. Meanwhile, Eumenes and his army had arrived at Cilicia, but had to retreat when Antigonus reached the city. The situation was difficult for Seleucus. Eumenes and his army were north of Babylon; Antigonus was following him with an even larger army; Peithon was in Media and his opponents in Susiana. Antigenes, satrap of Susiana and commander of the Argyraspides, was allied with Eumenes. Antigenes was in Cilicia when the war between him and Peithon began.[15]

Peithon arrived at Babylon in the autumn or winter of 317 BC. Peithon had lost a large number of troops, but Seleucus had even fewer soldiers. Eumenes decided to march to Susa in the spring of 316 BC. The satraps in Susa had apparently accepted Eumenes' claims of his fighting on behalf of the lawful ruling family against the usurper Antigonus. Eumenes marched his army 300 stadions away from Babylon and tried to cross the Tigris. Seleucus had to act. He sent two triremes and some smaller ships to stop the crossing. He also tried to get the former hypasiti of the Argyraspides to join him, but this did not happen. Seleucus also sent messages to Antigonus. Because of his lack of troops, Seleucus apparently had no plans to actually stop Eumenes. He opened the flood barriers of the river, but the resulting flood did not stop Eumenes.[16]

In the spring of 316 BC, Seleucus and Peithon joined Antigonus, who was following Eumenes to Susa. From Susa Antigonus went to Media, from where he could threaten the eastern provinces. He left Seleucus with a small number of troops to prevent Eumenes from reaching the Mediterranean. Sibyrtius, satrap of Arachosia, saw the situation as hopeless and returned to his own province. The armies of Eumenes and his allies were at breaking point. Antigonus and Eumenes had two encounters during 316 BC, in the battles of Paraitacene and Gabiene. Eumenes was defeated and executed. The events of the Second War of the Diadochi revealed Seleucus' ability to wait for the right moment. Blazing into battle was not his style.[17]

Escape to Egypt

Tetradrachm of Seleucos I. Obv Idealized portrait of Seleucos with a helmet covered with a leopard skin and decorated with a bull's ear and horns. Seleucus wears around his throat another leopard skin, knotted in front. Rev Winged figure of Nike (Victory). Nike holds a wreath over a trophy of arms including a helmet, a cuirass (breast-and-backplate) with leather straps and skirt, and a star-adorned shield, hung on a tree trunk. This a possible symbol of the Battle of Ipsus (301 BC). Legend "Seleucus" and "Basileus" (king).[18]

Antigonus spent the winter of 316 BC in Media, whose ruler was once again Peithon. Peithon's lust for power had grown, and he tried to get a portion of Antigonus' troops to revolt to his side. Antigonus, however, discovered the plot and executed Peithon. He then superseded Peucestas as satrap of Persia.[19] In the summer of 315 BC Antigonus arrived in Babylon and was warmly welcomed by Seleucus. The relationship between the two soon turned cold, however. Seleucus punished one of Antigonus' officers without asking permission from Antigonus. Antigonus became angry and demanded that Seleucus give him the income from the province, which Seleucus refused to do.[20] He was, however, afraid of Antigonus and fled to Egypt with 50 horsemen. It is told that Chaldean astrologers prophesied to Antigonus that Seleucus would become master of Asia and would kill Antigonus. After hearing this, Antigonus sent soldiers after Seleucus, who had however first escaped to Mesopotamia and then to Syria. Antigonus executed Blitor, the new satrap of Mesopotamia, for helping Seleucus. Modern scholars are skeptical of the prophecy story. It seems certain, however, that the Babylonian priesthood was against Seleucus.[21]

During Seleucus' escape to Egypt, Macedonia was undergoing great turmoil. Alexander the Great's mother Olympias had been invited back to Macedon by Polyperchon in order to drive Cassander out. She held great respect among the Macedonian army but lost some of this when she had Philip III and his wife Eurydice killed as well as many nobles whom she took revenge upon for supporting Antipater during his long reign. Cassander reclaimed Macedon the following year at Pydna and then had her killed. Alexander IV, still a young child, and his mother Roxane were held guarded at Amphipolis and died under mysterious circumstances in 310 BC, probably murdered at the instigation of Cassander to allow the diadochs to assume the title of king.

Admiral under Ptolemy (316–311 BC)

Main article: Third War of the Diadochi

After arriving in Egypt, Seleucus sent his friends to Greece to inform his fellow Diadochi Cassander (ruler of Macedon and overlord of Greece) and Lysimachus (ruler of Thracia) about Antigonus. Antigonus was now the most powerful of the Diadochi, and the others would soon have to face him. Ptolemy, Lysimachus and Cassander formed a coalition against Antigonus. The allies sent a proposition to Antigonus in which they demanded shares of his accumulated treasure and of his territory, with Phoenica and Syria going to Ptolemy, Cappadocia and Lycia to Cassander, Hellespontine Phrygia to Lysimachus, and Babylonia to Seleucus.[22] Antigonus refused, and in the spring of 314 BC, he marched against Ptolemy in Syria.[23] Seleucus acted as an admiral to Ptolemy during the first phase of the war. Antigonus was besieging Tyre,[24] when Seleucus sailed past him and went on to threaten the coast of Syria and Asia Minor. Antigonus allied with the island of Rhodes, which had a strategic location and a navy capable of preventing the allies from combining their forces. Because of the threat of Rhodes, Ptolemy gave Seleucus a hundred ships and sent him to the Aegean Sea. The fleet was too small to defeat Rhodes, but it was big enough to force Asander, the satrap of Caria, to ally with Ptolemy. To demonstrate his power, Seleucus also invaded the city of Erythrai. Polemaios, a nephew of Antigonus, attacked Asander. Seleucus returned to Cyprus, where Ptolemy I had sent his brother Menelaos along with 10,000 mercenaries and 100 ships. Seleucus and Menelaos began to besiege Kition. Antigonus sent most of his fleet to the Aegean Sea and his army to Asia Minor. Ptolemy now had an opportunity to invade Syria, where he defeated Demetrius, the son of Antigonus, in the battle of Gaza in 312 BC. It is probable that Seleucus took part in the battle. Peithon, son of Agenor, whom Antigonus had nominated as the new satrap of Babylon, fell in the battle. The death of Peithon gave Seleucus an opportunity to return to Babylon.[25]

Seleucus had prepared his return to Babylon well. After the battle of Gaza Demetrius retreated to Tripoli while Ptolemy advanced all the way to Sidon. Ptolemy gave Seleucus 800 infantry and 200 cavalry. He also had his friends accompanying him, perhaps the same 50 who escaped with him from Babylon. On the way to Babylon Seleucus recruited more soldiers from the colonies along the route. He finally had about 3,000 soldiers. In Babylon, Peithon's commander, Diphilus, barricaded himself in the city's fortress. Seleucus conquered Babylon with great speed and the fortress was also quickly captured. Seleucus' friends who had stayed in Babylon were released from captivity.[26] His return to Babylon was afterwards officially regarded as the beginning of the Seleucid Empire[2] and that year as the first of the Seleucid era.

Satrap of Babylonia (311– 306 BC)

Conquest of the eastern provinces

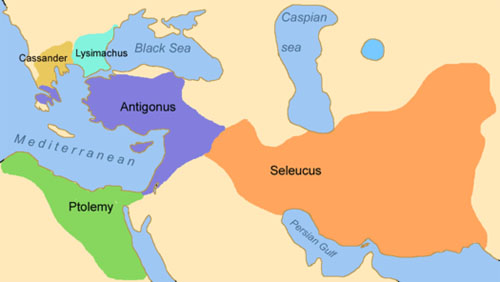

The kingdoms of Antigonus, Seleucus I, Ptolemy I, Cassander and Lysimachus

Soon after Seleucus' return, the supporters of Antigonus tried to get Babylon back. Nicanor was the new satrap of Media and the strategos of the eastern provinces. His army had about 17,000 soldiers. Evagoras, the satrap of Aria, was allied with him. It was obvious that Seleucus' small force could not defeat the two in battle. Seleucus hid his armies in the marshes that surrounded the area where Nicanor was planning to cross the Tigris and made a surprise attack during the night. Evagoras fell in the beginning of the battle and Nicanor was cut off from his forces. The news about the death of Evagoras spread among the soldiers, who started to surrender en masse. Almost all of them agreed to fight under Seleucus. Nicanor escaped with only a few men.[27]

Even though Seleucus now had about 20,000 soldiers, they were not enough to withstand the forces of Antigonus. He also did not know when Antigonus would begin his counterattack. On the other hand, he knew that at least two eastern provinces did not have a satrap. A great majority of his own troops were from these provinces. Some of Evagoras' troops were Persian. Perhaps a portion of the troops were Eumenes' soldiers, who had a reason to hate Antigonus. Seleucus decided to take advantage of this situation.[27]

Seleucus spread different stories among the provinces and the soldiers. According to one of them, he had in a dream seen Alexander standing beside him. Eumenes had tried to use a similar propaganda trick. Antigonus, who had been in Asia Minor while Seleucus had been in the east with Alexander, could not use Alexander in his own propaganda. Seleucus, being Macedonian, had the ability to gain the trust of the Macedonians among his troops, which was not the case with Eumenes.[28]

After becoming once again satrap of Babylon, Seleucus became much more aggressive in his politics. In a short time he conquered Media and Susiana. Diodorus Siculus reports that Seleucus also conquered other nearby areas, which might refer to Persis, Aria or Parthia. Seleucus did not reach Bactria and Sogdiana. The satrap of the former was Stasanor, who had remained neutral during the conflicts. After the defeat of Nikanor's army, there was no force in the east that could have opposed Seleucus. It is uncertain how Seleucus arranged the administration of the provinces he had conquered. Most satraps had died. In theory, Polyperchon was still the lawful successor of Antipater and the official regent of the Macedonian kingdom. It was his duty to select the satraps. However, Polyperchon was still allied with Antigonus and thus an enemy of Seleucus.[29]

Response

Seleucus I coin depicting Alexander the Great's horse Bucephalus

Antigonus sent his son Demetrius along with 15,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry to reconquer Babylon. Apparently, he gave Demetrius a time limit, after which he had to return to Syria. Antigonus believed Seleucus was still ruling only Babylon. Perhaps Nicanor had not told him that Seleucus now had at least 20,000 soldiers. It seems that the scale of Nicanor's defeat was not clear to all parties. Antigonus did not know Seleucus had conquered the majority of the eastern provinces and perhaps cared little about the eastern parts of the empire.[30]

When Demetrius arrived in Babylon, Seleucus was somewhere in the east. He had left Patrocles to defend the city. Babylon was defended in an unusual way. It had two strong fortresses, in which Seleucus had left his garrisons. The inhabitants of the city were transferred out and settled in the neighbouring areas, some as far as Susa. The surroundings of Babylon were excellent for defence, with cities, swamps, canals and rivers. Demetrius' troops started to besiege the fortresses of Babylon and conquered one of them. The second fortress proved more difficult for Demetrius. He left his friend Archelaus to continue the siege, and himself returned west leaving 5,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry in Babylon. Ancient sources do not mention what happened to these troops. Perhaps Seleucus had to reconquer Babylon from Archelaus.[31]

Babylonian War

Main article: Babylonian War

Coin of Lysimachus with an image of a horned Alexander the Great

Over the course of nine years (311–302 BC), while Antigonus was occupied in the west, Seleucus brought the whole eastern part of Alexander's empire as far as the Jaxartes and Indus Rivers under his authority.[2]

In 311 BC Antigonus made peace with Cassander, Lysimachus and Ptolemy, which gave him an opportunity to deal with Seleucus.[32] Antigonus' army had at least 80,000 soldiers. Even if he left half of his troops in the west, he would still have a numerical advantage over Seleucus. Seleucus may have received help from Cossaians, whose ancestors were the ancient Kassites. Antigonus had devastated their lands while fighting Eumenes. Seleucus perhaps recruited a portion of Archelaus' troops. When Antigonus finally invaded Babylon, Seleucus' army was much bigger than before. Many of his soldiers certainly hated Antigonus. The population of Babylon was also hostile. Seleucus, thus, did not need to garrison the area to keep the locals from revolting.[33]

Little information is available about the conflict between Antigonus and Seleucus; only a very rudimentary Babylonian chronicle detailing the events of the war remains. The description of the year 310 BC has completely disappeared. It seems that Antigonus conquered Babylon. His plans were disturbed, however, by Ptolemy, who made a surprise attack in Cilicia.[33]

We do know that Seleucus defeated Antigonus in at least one decisive battle. This battle is only mentioned in Stratagems in War by Polyaenus. Polyaenus reports that the troops of Seleucus and Antigonus fought for a whole day, but when night came the battle was still undecided. The two forces agreed to rest for the night and continue in the morning. Antigonus' troops slept without their equipment. Seleucus ordered his forces to sleep and eat breakfast in battle formation. Shortly before dawn, Seleucus' troops attacked the forces of Antigonus, who were still without their weapons and in disarray and thus easily defeated. The historical accuracy of the story is questionable.[34][35]

The Babylonian war finally ended in Seleucus' victory. Antigonus was forced to retreat west. Both sides fortified their borders. Antigonus built a series of fortresses along the Balikh River while Seleucus built a few cities, including Dura-Europos and Nisibis.

Seleucia

The next event connected to Seleucus was the founding of the city of Seleucia. The city was built on the shore of the Tigris probably in 307 or 305 BC. Seleucus made Seleucia his new capital, thus imitating Lysimachus, Cassander and Antigonus, all of whom had named cities after themselves. Seleucus also transferred the mint of Babylon to his new city. Babylon was soon left in the shadow of Seleucia, and the story goes that Antiochus, the son of Seleucus, moved the whole population of Babylon to his father's namesake capital in 275 BC. The city flourished until AD 165, when the Romans destroyed it.[34][36]

A story of the founding of the city goes as follows: Seleucus asked the Babylonian priests which day would be best to found the city. The priest calculated the day, but, wanting the founding to fail, told Seleucus a different date. The plot failed however, because when the correct day came, Seleucus' soldiers spontaneously started building the city. When questioned, the priests admitted their deed.[37]

King of the Seleucid empire (306–281 BC)

The struggle among the Diadochi reached its climax when Antigonus, after the extinction of the old royal line of Macedonia, proclaimed himself king[2] in 306 BC. Ptolemy, Lysimachus, Cassander and Seleucus soon followed. Also, Agathocles of Sicily declared himself king around the same time.[34][38] Seleucus, like the other four principal Macedonian chiefs, assumed the title and style of basileus (king).[2]

Chandragupta[??] and the Eastern Provinces

Main article: Seleucid–Mauryan war

Seleucus soon turned his attention once again eastward. The Persian provinces in what is now modern Afghanistan, together with the wealthy kingdom of Gandhara and the states of the Indus Valley, had all submitted to Alexander the Great and become part of his empire. When Alexander died, the Wars of the Diadochi ("Successors") split his empire apart; as his generals fought for control of Alexander's empire. In the eastern territories, Seleucus I Nicator took control of Alexander's conquests. According to the Roman historian Appian:

[Seleucus was] always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus.

— Appian, History of Rome, The Syrian Wars 55

The Mauryans then annexed the areas around the Indus governed by the four Greek satraps: Nicanor, Phillip, Eudemus and Peithon. This established Mauryan control to the banks of the Indus. Chandragupta's[??] victories convinced Seleucus that he needed to secure his eastern flank. Seeking to hold the Macedonian territories there, Seleucus thus came into conflict with the emerging and expanding Mauryan Empire over the Indus Valley.[39]

In the year 305 BC, Seleucus I Nicator went to India and apparently occupied territory as far as the Indus, and eventually waged war with the Maurya Emperor Chandragupta Maurya.[??][citation needed]