Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer

from Various Sources

********************

When Tibet finally lost her freedom in 1959 and the Dalai Lama was forced into exile, Rumbold, and old India hands like Sir Olaf Caroe (a former Foreign Secretary to the Indian Government and Governor of the North-West Frontier Province) and Hugh Richardson (Head of British Mission, Lhasa), joined with Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer to found the Tibet Society of the UK, an organisation that for many years stood alone in advocating Tibet's independence. Members of the society persistently challenged Chinese propaganda, principally by letters to the broadsheet papers, until the British media came to understand that there was a more reliable source for news about Tibet than the Anglo-China Association and the Chinese Ambassador.

For 11 years, from 1977 to 1988, Rumbold served the Tibet Society as its president. In 1991, with Hugh Richardson, he produced for the All Party Parliamentary Group on Tibet a pamphlet, Tibet, the Truth about Independence, which remains the most succinct and authoritative account of Tibet's status and the British government's relations with Tibet.

-- Obituary: Sir Algernon Rumbold, by John Billington

**********************

The Founding of Tibet Relief Fund

by Tibet Relief Fund

Accessed: 3/7/20

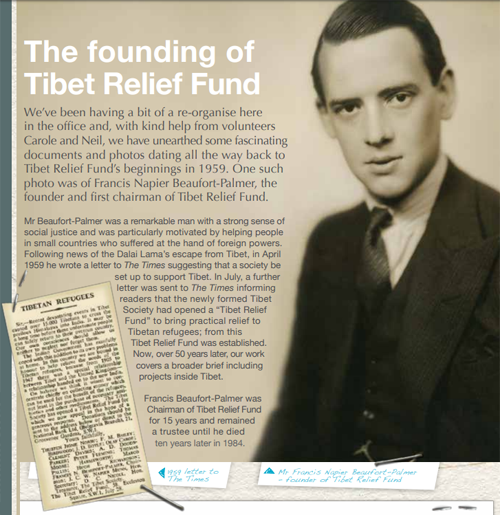

We've been having a bit of re-organise here in the office and, with kind help from volunteers Carole and Neil, we have unearthed some fascinating documents and photos dating all the way back to Tibet Relief Fund's beginnings in 1959. One such photo was of Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer, the founder and first chairman of Tibet Relief Fund.

Mr. Beaufort-Palmer was a remarkable man with a strong sense of social justice and was particularly motivated by helping people in small countries who suffered at the hand of foreign powers. Following news of the Dalai Lama's escape from Tibet, in April 1959 he wrote a letter to The Times suggesting that a society be set up to support Tibet. In July, a further letter was sent to The Times informing readers that the newly formed Tibet Society had opened a "Tibet Relief Fund" to bring practical relief to Tibetan refugees; from this Tibet Relief Fund was established. Now, over 50 years later, our work covers a broader brief including projects inside Tibet.

Francis Beaufort-Palmer was Chairman of Tibet Relief Fund for 15 years and remained a trustee until he died ten years later in 1984.

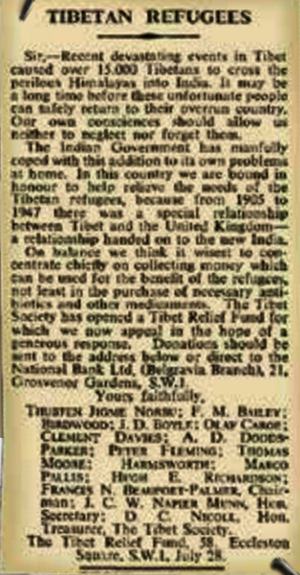

TIBETAN REFUGEES

Sir. – Recent devastating events in Tibet caused over 15,000 Tibetans to cross the perilous Himalayas into India. It may be a long time before these unfortunate people can safely return to their overrun country. Our own consciences should allow us neither to neglect nor forget them.

The Indian Government has manfully coped with this addition to its own problems at home. In this country we are bound in honour to help relieve needs of the Tibetan refugees, because from 1905 to 1947 there was a special relationship between Tibet and the United Kingdom – a relationship handed on to the new India.

On balance we think it wisest to concentrate chiefly on collecting money which can be used for the benefit of the refugees, not least in the purchase of necessary antibiotics and other medicaments. The Tibet Society has opened a Tibet Relief Fund for which we now appeal in the hope of a generous response. Donations should be sent to the address below or direct to the National Bank Ltd. (Belgravia Branch), 21 Grosvenor Gardens, S.W.I.

Yours faithfully,

Thubten Jigme Norbu; F.M. Bailey; Birdwood; J.D. Boyle; [Indian Foreign Secretary Sir] Olaf Caroe; Clement Davies; A.D. Dodds-Parker; Peter Fleming [Master of Deception: The Wartime Adventures of Peter Fleming, by Alan Ogden]; Thomas Moore; [Esmond Harmsworth, 2nd Viscount Rothermere] Harmsworth; Marco Pallis; Hugh E. Richardson; Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer, Chairman; Major J.C.W. Napier-Munn [Tac HQ Calcutta (Advanced HQ ALFSEA)], Hon. Secretary; D.C. Nicole, Hon. Treasurer, The Tibet Society.

The Tibet Relief Fund, 58 Eccleston Square, S.W. I., Letter to the Times, July 31, 1959, p.7./quote]

-- The Founding of Tibet Relief Fund, Tibet Matters, Issue 17, Autumn 2013, by Tibet Relief Fund

****************************

ADMINISTRATIVE AND SPECIAL DUTIES BRANCH

The London Gazette

January 21, 1941

P. 417-418

The undermentioned are granted commissions for the duration of hostilities: --

As Pilot Officers on probation....

19th Dec. 1940.

Francis Napier BEAUFORT-PALMER (89510).

***************************

OFFICERS SERVING ON THE ACTIVE LIST OF THE R.A.F.

by National Library of Scotland

Accessed: 7/4/21

Administrative and Special Duties Branch

Pilot Officers

1940

(R.A.F.V.R.) P.

Beaufort - Palmer, Francis Napier

***************************

The Sphere

An Illustrated Newspaper for the Home

May 16, 1925

Content:

20. In the Public Eye - Small pictures of: Sir William Ramsey, Madame Edvina, Dr George A Reisner, Mr Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer, Sir Frank Dicksee, Miss Lula Vollmer, Miss Nadine March, Miss Barbara Cartland.

**************************

Department of Manuscripts: Acquisitions, January 1973 to December 1974

The British Library Journal

Vol. 1, No. 2 , pp. 191-196 (6 pages)

AUTUMN 1975

RECENT ACQUISITIONS

Department of Manuscripts

Acquisitions, January 1973 to December 1974

The following list includes manuscripts incorporated into the collections between January 1973 and December 1974. The inclusion of a manuscript in this list does not necessarily imply that it is available for study....

Correspondence and papers of the Napier family, supplementing Add.MSS. 49086-49172, 54510-54564; 1790-1865. Add.MS. 58209; Add.Ch.75767, 75769-75790. Presented by the executors of Mrs. Violet Bunbury Napier.

Benjamin Disraeli, Earl of Beaconsfield: correspondence, memoranda, etc.; 1867-73, n.d. Add. MSS 58079V presented by F.N. Beaufort-Palmer, Esq.; 58210

***************************

-- The life and letters of Lady Sarah Lennox, 1745-1826, daughter of Charles, 2nd duke of Richmond, and successively the wife of Sir Thomas Charles Bunbury, and of the Hon. George Napier; also a short political sketch of the years 1760 to 1763, by Henry Fox, 1st lord Holland; by Napier, Lady Sarah Lennox Bunbury, 1745-1826; Holland, Henry Fox, Baron, 1705-1774; Ilchester, Mary Eleanor Anne Dawson, countess of; Ilchester, Giles Stephen Holland Fox-Strangways, Earl of, b. 1874; Napier, Henry Edward, 1789-1853

***************************

George Napier

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/4/21

Colonel The Honourable

George Napier

Col. George Napier

Born: 11 March 1751

Died: 12 October 1804 (aged 53)

Allegiance: Great Britain

Service/branch: British Army

Years of service: 1767–1804

Rank: Colonel

Battles/wars: American War of Independence

Spouse(s): Elizabeth Pollock (m. 1775; died 1778); Lady Sarah Lennox (m. 1781)

Children: Henry Napier; Louisa Mary Napier; Sir Charles James Napier; Emily Bunbury, Lady Bunbury; Sir George Thomas Napier; Sir William Francis Patrick Napier; Richard Napier; Henry Edward Napier; Caroline Napier; Cecilia Napier

Colonel George Napier (11 March 1751 – 13 October 1804), styled "The Honourable", was a British Army officer, most notable for his marriage to Lady Sarah Lennox, and for his sons Charles James Napier, William Francis Patrick Napier and George Thomas Napier, all of whom were noted military officers, collectively referred to as "Wellington’s Colonels". He also served as Comptroller of Army Accounts in Ireland from 1799 until his death in 1804.

Birth

George Napier was the younger son of Francis Napier, 6th Lord Napier and his wife Henrietta Maria Johnston.

Military service

Napier was commissioned into the 25th Foot in 1767 and was promoted Lieutenant in 1771. He became the regiment's Quartermaster in 1776. In 1778 he transferred to the 80th Regiment of Foot (Royal Edinburgh Volunteers) as a Captain. He served in the American War of Independence on the staff of Sir Henry Clinton.[1] He sold his commission in 1781, but was commissioned into the 1st Foot Guards in 1782. In 1783 he transferred to the 100th Regiment of Foot (Loyal Lincolnshire Regiment) as a Captain. In 1794 he was promoted Major, transferred to the 87th Foot, and then transferred again to the newly raised Londonderry Regiment as Lieutenant-Colonel. In 1800 he was promoted Colonel.

Marriages

On 22 January 1775 he married Elizabeth Pollock (died 1778), and together they had one daughter, Louisa Mary Napier (died 1856) and one son, Henry Napier, born 1778.

On 27 August 1781 he married Lady Sarah Lennox, daughter of Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond. He was described at the time as being “impoverished”. Her previous marriage had ended in scandal and divorce; George was Sarah's second husband, Sarah was George's second wife. Together they raised eight children, including three who were to become famed military officers:

• General Sir Charles James Napier GCB (10 August 1782 – 1853)

• Emily Louisa Augusta Napier (1783 – 1863), married Sir Henry Bunbury, 7th Baronet

• Lieutenant-General Sir George Thomas Napier KCB (1784 – 1855)

• Lieutenant-General Sir William Francis Patrick Napier KCB (17 December 1785 – 12 February 1860)

• Richard Napier (1787 – 1868) married Anna Louisa Stewart, daughter of Sir J. Stewart.

• Captain Henry Edward Napier RN (5 March 1789 – 13 October 1853)

• Caroline Napier (1790 - 1810)

• Cecilia Napier (1791 - 1808)

In 1785 he moved his family to Celbridge in County Kildare, Ireland, where George eventually earned a post as Comptroller of Army Accounts. Lady Sarah was the sister of the very wealthy Lady Louisa Conolly and Emily FitzGerald, Duchess of Leinster who lived nearby.[2] During the Irish Rebellion of 1798, in which one of the rebel leaders was his nephew Lord Edward FitzGerald, he is said to have armed his five sons, put his house in a state of defence, and offered an asylum to all who were willing to resist the insurgents.[3][4]

Trivia

In 1999, a 6-part miniseries called Aristocrats, based on the lives of Sarah Lennox and her sisters, aired in the U.K. George Napier appears at various ages in the series, played by Martin Glyn Murray and Jeremy Bulloch.[5]

It is incorrectly stated that George Napier's grandson, Colonel Napier, brought the first pair of skis to Davos in 1888, starting the popular sport of Alpine skiing that had formerly been the activity of a few experts. The actual "Colonel Napier" who was responsible for the growth of Alpine skiing was the son of Robert Napier, 1st Baron Napier of Magdala[6]

References and notes

1. Hibbert, Christopher, "Wellington: A Personal History", Addison-Wesley, 1997, Chapter 1. From NY Times "Books" on-line, accessed 2008-11-21.

2. Stella Tillyard “Aristocrats" (1998)

3. Bloy, Marjorie, "Sir William Francis Patrick Napier (1785-1860)", British Foreign Policy 1815-65, historyhome.co.uk, accessed 2008-11-21.

4. Lee, Sidney, ed. (1894). "Napier, Charles James" . Dictionary of National Biography. 40. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

5. "Aristocrats" (1999), IMDb.com, accessed 2008-11-21.

6. "Skiing Heritage Journal". September 1993.

External links

• "Introduction Bunbury Papers" (PDF). - letters written to Sarah Lennox/Bunbury

• Lt.-Gen. Sir George Thomas Napier, thePeerage.com, accessed 2008-11-21.

***************************

Lady Sarah Lennox

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/4/21

Lady Sarah Lennox

Lady Sarah Bunbury Sacrificing to the Graces by Sir Joshua Reynolds, 1765

Born: 14 February 1745

Died: August 1826 (aged 81)

Spouse(s): Sir Charles Bunbury, 6th Baronet (m. 1762; div. 1776); Hon. George Napier (m. 1781; died 1804)

Children: Louisa Bunbury; Sir Charles James Napier; Emily Napier; Sir George Thomas Napier; Sir William Francis Patrick Napier; Richard Napier; Henry Edward Napier; Caroline Napier; Cecilia Napier

Parent(s): Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond; Sarah Cadogan

Lady Sarah Lennox (14 February 1745 – August 1826) was the most notorious of the famous Lennox sisters, daughters of Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond.

Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond, 2nd Duke of Lennox, 2nd Duke of Aubigny, KG, KB, PC, FRS (18 May 1701 – 8 August 1750) of Goodwood House near Chichester in Sussex, was a British nobleman and politician. He was the son of Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond, 1st Duke of Lennox, the youngest of the seven illegitimate sons of King Charles II. He was the most important of the early patrons of the game of cricket and did much to help its evolution from village cricket to first-class cricket.

Lennox was styled Earl of March from his birth in 1701 as heir to his father's dukedom. He also inherited his father's love of sports, particularly cricket. He had a serious accident at the age of 12 when he was thrown from a horse during a hunt, but he recovered and it did not deter him from horsemanship.

March entered into an arranged marriage in December 1719 when he was still only 18 and his bride, Hon. Sarah Cadogan, was just 13, in order to use Sarah's large dowry to pay his considerable debts. They were married at The Hague.

In 1722, March became Member of Parliament for Chichester as first member with Sir Thomas Miller as his second. He gave up his seat after his father died in May 1723 and he succeeded to the title of 2nd Duke of Richmond. A feature of Richmond's career was the support he received from his wife, Sarah [Cadogan], her interest being evident in surviving letters. Their marriage was a great success, especially by Georgian standards.

Their grandson who became the 4th Duke is known to cricket history as the Hon. Col. Charles Lennox, a noted amateur batsman of the late 18th century who was one of Thomas Lord's main guarantors when he established his new ground in Marylebone.

-- Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond

Early life

After the deaths of both her parents when she was only five years old, Lady Sarah was brought up by her elder sister Emily in Ireland. Lady Sarah returned to London and the home of her sister Lady Caroline Fox when she was thirteen. Having been a favourite of King George II since her childhood, she was invited to appear at court and there caught the eye of George, Prince of Wales (the future King George III), whom she had met as a child.[1]

When she was presented at court again at the age of fifteen, George III was taken with her. Lady Sarah's family encouraged a relationship between her and George III.[2] Lady Sarah had also developed feelings for Lord Newbattle, grandson of William Kerr, 3rd Marquess of Lothian. Although her family were able to persuade her to break with Newbattle, the royal match was scotched by the King's advisors, particularly John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute. It was not normal at the time for monarchs to have non-Royal spouses. Lady Sarah was asked by King George III to be one of the ten bridesmaids at his wedding to Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.[3]

Family and marriages

Lady Sarah refused a proposal of marriage from James Hay, 15th Earl of Erroll, before marrying Charles Bunbury, eldest son of Reverend Sir William Bunbury, 5th Baronet, on 2 June 1762 at Holland House Chapel, Kensington, London. He succeeded his father as sixth Baronet in 1764.

Lady Sarah had an affair with Lord William Gordon, the second son of the Duke of Gordon, and gave birth to his illegitimate daughter in 1768. The child was not immediately disclaimed by Sir Charles, and received the name Louisa Bunbury. Nevertheless, Lady Sarah and Lord William eloped shortly afterwards, in February 1769, taking the infant with them. Lord William soon abandoned her. Sir Charles refused to take her back, and Lady Sarah returned to her brother's house with her child, while her husband introduced into Parliament a motion for a divorce on grounds of adultery, citing her elopement. Lady Sarah resisted the motion, and it was not until 14 May 1776 that the decree of divorce was issued.

Lady Sarah married an army officer, Hon. George Napier, on 27 August 1781 and had eight children:

• General Sir Charles James Napier (10 August 1782 – 29 August 1853); married Elizabeth Oakeley in April 1827. He remarried Frances Philipp in 1835.

• Emily Louisa Augusta Napier (11 July 1783 – 18 March 1863); married Lt.-Gen. Sir Henry Bunbury, 7th Baronet (nephew of her mother's first husband) on 22 September 1830

• Lieutenant-General Sir George Thomas Napier (30 June 1784 – 8 September 1855); married Margaret Craig on 22 October 1812. They had five children. He married Frances Blencowe in 1839.

• Lieutenant-General Sir William Francis Patrick Napier KCB (17 December 1785 – 12 February 1860); married Caroline Fox (granddaughter of his aunt Lady Caroline Fox) on 14 March 1812. They had five children.

• Richard Napier (1787 – 13 January 1868); married Anna Louisa Stewart, daughter of Sir J. Stewart, in 1817.

• Captain Henry Edward Napier RN (5 March 1789 – 13 October 1853); married Caroline Bennett. They had three children.

• Caroline Napier (1790–1810); died at the age of twenty.

• Cecilia Napier (1791–1808); died at the age of seventeen.

In popular culture

In 1999, a six-part mini-series based on the lives of Sarah Lennox and her sisters aired in the UK. It was called Aristocrats, and Sarah was played by actress Jodhi May.[4]

References

1. "Lady Sarah Bunbury Sacrificing to the Graces". Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

2. Napier, Priscilla (1971). The Sword Dance: Lady Sarah Lennox and the Napiers. New York: McGraw-Hill.

3. "Holland House and its history Pages 161-177 Old and New London: Volume 5. Originally published by Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London, 1878". British History Online.

4. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0204082/maindetails[bare URL]

• Ilchester, ed., Countess (1901). The Life and Letters of Lady Sarah Lennox, 1745–1826. London: John Murray.

o "Review of The Life and Letters of Lady Sarah Lennox, 1745–1826 edited by the Countess of Ilchester and Lord Stavordale". The Quarterly Review. 195: 274–294. January 1902.

• Curtis, Edith R. (1946). Lady Sarah Lennox: An Irrepressible Stuart, 1745–1826. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

• Hall, Thornton (2004). Love Romances of the Aristocracy.

• Napier, Priscilla (1971). The Sword Dance: Lady Sarah Lennox and the Napiers. New York: McGraw-Hill.

• Tillyard, Stella (1994). Aristocrats: Caroline, Emily, Louisa, and Sarah Lennox, 1740–1826. London: Chatto & Windus.

****************************

Francis Beaufort

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/4/21

Sir Francis Beaufort, KCB [Order of the Bath] FRS [Fellow of the Royal Society] FRGS [Royal Geographical Society] FRAS [Royal Astronomical Society] MRIA [Royal Irish Academy]

Beaufort c. 1851

Hydrographer of the Navy

In office: 19 May 1829 – 25 January 1855

Preceded by: Sir Edward Parry

Succeeded by: John Washington

Personal details

Born: 27 May 1774, Navan, County Meath, Ireland

Died: 17 December 1857 (aged 83), Hove, Sussex, England

Resting place: St John's Church Gardens

Spouse(s): Alicia Wilson (1815–1834); Honora Edgeworth (1838–1857)

Children: Francis Lestock Beaufort; Emily Anne Beaufort

Father: Daniel Augustus Beaufort

Relatives: Frances Beaufort (sister); Henrietta Beaufort (sister); Daniel de Beaufort (grandfather)

Occupation: Hydrographer, mariner

Known for: Beaufort cipher, Beaufort scale

Awards: Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (1848)

Military service

Branch: Royal Navy

Service years: 1790–1855

Rank: Rear admiral

Wars: French Revolutionary Wars; Napoleonic Wars

Sir Francis Beaufort KCB FRS FRGS FRAS MRIA (/ˈboʊfət/; 27 May 1774 – 17 December 1857) was an Irish hydrographer, rear admiral of the Royal Navy, and creator of the Beaufort cipher and the Beaufort scale.

Early life

Francis Beaufort was descended from French Protestant Huguenots, who fled the French Wars of Religion in the sixteenth century. His parents moved to Ireland from London. His father, Daniel Augustus Beaufort, was a Protestant clergyman from Navan, County Meath, Ireland, and a member of the learned Royal Irish Academy. His mother Mary was the daughter and co-heiress of William Waller, of Allenstown House. Francis was born in Navan on 27 May 1774.[1] He had an older brother, William Louis Beaufort and three sisters, Frances, Harriet, and Louisa. His father created and published a new map of Ireland in 1792.[2] Francis grew up in Wales and Ireland until age fourteen.[3][4] He left school and went to sea, but never stopped his education. By later in life, he had become sufficiently self-educated to associate with some of the greatest scientists and applied mathematicians of his time, including Mary Somerville, John Herschel, George Biddell Airy, and Charles Babbage.

Francis Beaufort had a lifelong keen awareness of the value of accurate charts for those risking the seas, as he was shipwrecked at the age of fifteen due to a faulty chart. His most significant accomplishments were in nautical charting.

Career

Early naval career

Beginning on a merchant ship of the British East India Company, Beaufort rose to midshipman during the Napoleonic Wars, to lieutenant on 10 May 1796, and commander on 13 November 1800. He served on the fifth rate frigate HMS Aquilon during the Battle of the Glorious First of June off Ushant in Brittany in 1794, when Aquilon rescued the dismasted HMS Defence and exchanged broadsides with the French ship-of-the line, Impétueux.

When serving on HMS Phaeton, Beaufort was badly wounded leading a cutting-out operation off Málaga in 1800; the action resulted in the capture of the 14-gun polacca Calpe. While recovering, during which he received a "paltry" pension of £45 per annum, he helped his brother-in-law, Richard Lovell Edgeworth, to construct a semaphore line [An optical telegraph is a semaphore system using a line of stations, typically towers, for the purpose of conveying textual information by means of visual signals] from Dublin to Galway. He spent two years at this activity, for which he would accept no remuneration.[5]

Command

Beaufort returned to active service and was appointed a captain in the Royal Navy on 30 May 1810. Whereas other wartime officers sought leisurely pursuits, Beaufort spent his leisure time taking depth soundings and bearings, making astronomical observations to determine longitude and latitude, and measuring shorelines. His results were compiled in new charts.

The Admiralty gave Beaufort his first ship command, HMS Woolwich. He sailed her to the East Indies and escorted a convoy of East Indiamen back to Britain. The Admiralty then tasked him with conducting a hydrographic survey of the Rio de la Plata estuary in South America. Experts were very impressed by the survey Beaufort brought back. Notably, Alexander Dalrymple remarked in a note to the Admiralty in March 1808, that "we have few officers (indeed I do not know one) in our Service who have half his professional knowledge and ability, and in zeal and perseverance he cannot be excelled."[6]

Anatolia

After the Woolwich, Beaufort received his first post-captain commission, commanding Frederickstein.[7]

Throughout 1811–1812, Beaufort charted and explored southern Anatolia, a region he referred to as Karamania, locating many classical ruins, including Hadrian's Gate [Hadrian's Gate is a triumphal arch located in Antalya, Turkey, which was built in the name of the Roman emperor Hadrian, who visited the city in the year 130]. An attack on the crew of his boat (at Ayas, near Adana), by Turks interrupted his work and he received a serious bullet wound in the hip. He returned to England and drew up his charts.

In 1817, he published his book Karamania; or a brief description of the South Coast of Asia Minor, and of the Remains of Antiquity.[8]

Hydrographer of the Navy

In 1829, Beaufort was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society,[9] and in the same year, at the age of 55 (retirement age for most administrative contemporaries), Beaufort was appointed as the British Admiralty Hydrographer of the Navy. He served in that post for 26 years, longer than any other Hydrographer. G.S. Ritchie, himself Hydrographer (1966–1971) described this period as the "High Noon" of Admiralty surveying.[10]:189–199 The geographical scope of surveying was greatly increased, both in home waters and overseas. The production of new charts increased from 19 in 1830 to 1230 in 1855.[10]:196

In 1831 a Scientific Branch of the Admiralty was formed, which as well as the Hydrographic Department included the great astronomical observatories at Greenwich, England, and the Cape of Good Hope, Africa, and the Nautical Almanac and Chronometer Offices, and Beaufort was responsible for the administration.[10]:195 Beaufort directed some of the major maritime explorations and experiments of that period. He played a leading role in the search for the explorer, Sir John Franklin, who was lost during his last polar voyage to search for the legendary Northwest Passage.[11]

Beaufort was interested in scientific affairs beyond the confines of navigation. As a council member of the Royal Society, the Royal Observatory, and the Royal Geographical Society (which he helped found), Beaufort used his position and prestige as a top administrator to act as a "middleman" for many scientists of his time. Beaufort represented the geographers, astronomers, oceanographers, geodesists, and meteorologists to that government agency, the Hydrographic Office, which could support their research. In 1849 he assisted in the publication of the Admiralty Manual of Scientific Enquiry, to assist both Navy personnel and general travellers in scientific investigations, ranging from astronomy to ethnography.[12][10]:198

Beaufort trained Robert FitzRoy, who was put in temporary command of the survey ship HMS Beagle after her previous captain committed suicide. When FitzRoy was reappointed as commander for what became the famous second voyage of the Beagle, he requested of Beaufort "that a well-educated and scientific gentleman be sought" as a companion on the voyage.[10]:203 Beaufort's enquiries led to an invitation to Charles Darwin, who later drew on his discoveries in formulating the theory of evolution he presented in his book The Origin of Species. Later, when Beaufort persuaded the Board of Trade to set up a Meterorological Department, Fitzroy became its first Director[10]:192

Using his many connections, including the Royal Society, Beaufort helped to obtain funding for the Antarctic voyage of 1839–1843 by James Clark Ross for extensive measurements of terrestrial magnetism, coordinated with similar measurements in Europe and Asia.[3]:303 (This is comparable to the International Geophysical Year of our time.)

Beaufort promoted the development of reliable tide tables around British shores, publishing the first edition of the Admiralty Tide Tables in 1833.[13][14] This inspired similar research for Europe and North America. Aiding his friend William Whewell, Beaufort gained the support of the Prime Minister, Duke of Wellington, in expanding record-keeping at 200 British Coastguard stations. Beaufort gave enthusiastic support to his friend, Sir George Airy, the Astronomer Royal and noted mathematician, in achieving a historic period of measurements by the Greenwich and Good Hope observatories.

By the time Beaufort retired the Admiralty Chart series was a truly world wide resource with 2,000 charts covering every sea.[15]

Retirement

Beaufort retired from the Royal Navy with the rank of rear admiral on 1 October 1846, at the age of 72. He became "Sir Francis Beaufort" on being appointed KCB (Knight Commander of the Bath) on 29 April 1848, a relatively belated honorific considering the eminence of his position from 1829 onward. In 1840, he was elected to the American Philosophical Society.[16]

Personal life

Beaufort's extant correspondence of 200+ letters and journals contained portions written in personal cipher. Beaufort altered the Vigenère cipher, by reversing the cipher alphabet, and the resulting variant is called the Beaufort cipher. The deciphered writings have revealed family and personal problems, including some of a sexual nature. It appears that between 1835 and his marriage to Honora Edgeworth in November 1838, he had incestuous relations with his sister Harriet. His diary entries, in cypher, show that he was tortured by guilt over this.[3]

The Beaufort family tomb in St John's Church Gardens, London

He died on 17 December 1857, at age 83 in Hove, Sussex, England. He is buried in the church gardens of St John at Hackney, London, where his tomb may still be seen. His home in London, No. 51 Manchester Street, Westminster, is marked by an historic blue plaque noting his residency and achievements.[17]

Family

Beaufort married, firstly, Alicia Magdalena Wilson, daughter of Lestock Wilson R.N. under whom he had first served; she died in 1834.[18] Of their children, three daughters and three sons were living in 1859.[19] They included:

• Daniel Augustus Beaufort (1813/4–1898), cleric, married in 1851 Emily Nowell Davis, daughter of Sir John Francis Davis, 1st Baronet.[20][21]

Sir John Francis Davis, 1st Baronet KCB (16 July 1795 – 13 November 1890) was a British diplomat and sinologist who served as second Governor of Hong Kong from 1844 to 1848. Davis was the first President of Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong.

Davis was the eldest son of East India Company director and amateur artist Samuel Davis while his mother was Henrietta Boileau, member of a refugee French noble family who had come to England in the early eighteenth century from Languedoc in the south of France.Samuel Davis (1760–1819) was an English soldier turned diplomat who later became a director of the East India Company (EIC). He was the father of John Francis Davis, one time Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China and second governor of Hong Kong.

Samuel was born in the West Indies the younger son of soldier John Davis, whose appointment as Commissary general there had been signed by King George II in 1759 and countersigned by William Pitt. After his father died, Davis returned to England with his mother (who was of Welsh descent, née Phillips) and his two sisters. He became a cadet of the EIC under the aegis of director Laurence Sulivan in 1788, and sailed for India aboard the Earl of Oxford, which also brought the artist William Hodges to India, arriving in Madras in early 1780.

In 1783, Warren Hastings, the Governor of the Presidency of Fort William (Bengal) assigned Davis "Draftsman and Surveyor" on Samuel Turner's forthcoming mission to Bhutan and Tibet. Unfortunately, the Tibetans (or more probably the Chinese ambans, the de facto authority in Tibet) viewed his "scientific" profession with suspicion and he was forced to remain in Bhutan until Turner and the others returned. Whilst in Bhutan he turned his attention to recording the buildings and landscape of the country in a series of drawings. These were published some 200 years later as Views of Medieval Bhutan: the diary and drawings of Samuel Davis, 1783.

On his return from Bhutan, in around 1784 he became Assistant to the Collector of Bhagalpur and Registrar of its Adalat Court. In Bhagalpur he met lawyer and orientalist William Jones who had recently founded The Asiatic Society of which Davis subsequently became a member. The two became firm friends based on their shared love of mathematics while along with another member of The Asiatic Society, Reuben Burrow, Davis studied astronomical tables obtained by the French astronomer Guillaume Le Gentil, French Resident at the Faizabad court of Shuja-ud-Daula who in turn had obtained them from Tiruvallur Brahmins on the Coromandel Coast. The tables showed accurate Indian scientific knowledge of astronomy dating back to the third century BCE. As part of his research, Davis also learned Sanskrit and Hindi. For the next ten years, Jones and Davis carried on a running correspondence on the topic of jyotisha or Hindu astronomy. While in Bhagalpur, Davis also met landscape artist Thomas Daniell and his nephew William whom he encouraged to visit the Himalayas. In 1792 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.

Davis' next appointment was as Collector of Burdwan, a town in the Bengal Presidency. He then spent 1795–1800 in Benares (now Varanasi), this time as Magistrate of the district and city court. Benares was also home to former ruler of Oudh State, Wazir Ali Khan, who had been forcibly deposed by the British in 1797. In 1799, the British authorities decided to remove Ali Khan further from his former realm and as a result rioting broke out. Davis singlehandly defended his family by shepherding them to the roof of his residence and defending the single access point with a pike. The incident was the subject of a book by his son, John F. Davis, entitled Vizier Ali Khan or The Massacre of Benares, A Chapter in British Indian History published in London in 1871.

During the remainder of his stay in India, Davis held a succession of more senior positions including Superintendent-General of Police and Justice of the Peace at Calcutta, member of the Board of Revenue and Accountant-General of India. He resigned from the civil service in February 1806 and after a stop at St. Helena to engage in his love for painting, arrived back in England in July the same year.

He was elected a director of the EIC in October at the instigation of President of the Board of Control, Henry Dundas and to the latter's disgust, acted independently thereafter until his death in 1819.

"At the time of the renewal of the [company's] Charter in 1814, the Committee of the House of Commons entrusted him [Davis] with the task of drawing up, in their name, the memorable "Fifth Report on the Revenues of Bengal", which remains a monument of his intimate acquaintance with the internal administration of India"

While in Burdwan, Davis married Henrietta Boileau, who was from a refugee French noble family who had come to England in the early eighteenth century from Languedoc in the South of France. She was the first cousin of John Boileau, 1st Baronet of Tacolnestone Hall in Norfolk. The couple went on to have four sons and seven daughters. Their eldest son John Francis Davis, became second Governor of Hong Kong followed by Lestock-Francis and Sullivan, both of whom died in India in 1820 and 1821 respectively. Their daughters were as follows:

• Henrietta-Anne, who married Henry Baynes Ward in 1821.

• Anne, who married Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Dundas Campbell in 1827

• Maria–Jane, who married Lieutenant Colonel John Rivett-Carnac, RN in 1826.[10]

• Elizabeth, who married Sir Henry Willock, KLS.

• Frances, who died in 1828.

• Alicia, who married the Reverend John Lockwood, rector of Kingham in 1832.

• Julia, who in 1839 married John Edwardes Lyall, Advocate-General of Bengal, who died in 1845 of cholera.[/b][/size]

-- Samuel Davis (orientalist), by Wikipedia

In 1813, Davis was appointed writer at the East India Company's factory in Canton (now Guangzhou), China, at the time the centre of trade with China. Having demonstrated the depth of his learning in the Chinese language in his translation of The Three Dedicated Rooms ("San-Yu-Low") in 1815, he was chosen to accompany Lord Amherst on his embassy to Peking in 1816.

On the mission's return Davis returned to his duties at the Canton factory, and was promoted to president in 1832. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society the same year.

Davis was appointed Second Superintendent of British Trade in China alongside Lord Napier in December 1833, superseding William Henry Chicheley Plowden in the latter's absence. After Napier's death in 1834, Davis became Chief Superintendent then resigned his position in January 1835, to be replaced by Sir George Robinson. Davis left Canton aboard the Asia on 12 January.

In 1839, Davis purchased the Regency mansion Holly House, near Henbury, Bristol, where he built an observatory tower built housing a clock installed by Edward John Dent, who would later be responsible for building Big Ben. It remained the Davis family home for seven decades thereafter.

Governor of Hong Kong

Having arrived from Bombay on HMS Spiteful on 7 May 1844, he was appointed governor and commander-in-chief of Hong Kong the next day.:47 During his tenure, Davis was unpopular with Hong Kong residents and British merchants due to the imposition of various taxes, which increased the burden of all citizens, and his abrasive treatment of his subordinates. Davis organised the first Hong Kong Census in 1844, which recorded that there were 23,988 people living in Hong Kong.

In the same year, Davis exhorted China to abandon the prohibition on opium trade, on the basis of its counter productiveness, relating that, in England,... the system of prohibitions and high duties ... only increased the extent of smuggling, together with crimes of violence, while they diminished the revenue; until it was a length found that the fruitless expense of a large preventive force absorbed much of the amount of duty that could be collected, while prohibited articles were consumed more than ever.

Weekend horse racing began during his tenure, which gradually evolved into a Hong Kong institution. Davis founded the China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1847 and he was its first president.

Davis left office on 21 March 1848, ending unrelenting tensions with local British merchants who saw him as a stingy, arrogant and obstinate snob. His early decision to exclude all but government officials from the Executive and Legislative Councils on the basis that "almost every person possessed of Capital, who is not connected with Government Employment, is employed in the Opium trade" could not have made co-operation any easier. He departed the colony on 30 March via the P&O steamer Pekin. He returned to England, where he rejoined Emily, who had stayed there throughout his governorship.

Personal life

Davis married Emily, the daughter of Lieutenant Colonel Humfrays of the Bengal Engineers in 1822. They had one son and six daughters:[2]

• Sulivan (13 January 1827 – 1862); died in Bengal.

• Henrietta Anne

• Emily Nowell; married Reverend D. A. Beaufort in 1851, eldest son of Francis Beaufort, the inventor of the eponymous wind scale.

• Julia Sullivan; married Robert Cann Lippincott in 1854

• Helen Marian (died 31 January 1859)

• Florence

• Eliza (died 20 October 1855)

In 1867, a year after the death of his wife Emily, Davis married Lucy Ellen, eldest daughter of Reverend T. J. Locke, vicar of Exmouth, in 1867. A son, Francis Boileau, was born in 1871.

He was a created a baronet on 9 July 1845 and appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath (KCB) on 12 June 1854. Having retired from government, Davis engaged in literary pursuits. In 1876, he became a Doctor of Civil Law of the University of Oxford after a donation of £1,666 in three percent consol bonds to endow a scholarship in his name for the encouragement of the study of Chinese.

-- John Francis Davis, by Wikipedia

• Francis Lestock Beaufort (1815–1879), served in the Bengal civil service, from 1837 to 1876.[22]

Francis Lestock Beaufort (1815–1879), was a son of Sir Francis Beaufort and the author of the Digest of I Criminal Law Procedure in Bengal (1850).

-- Francis Lestock Beaufort, by Wikipedia

• Sophia Mary Bonne married the Rev. William Palmer in 1838.[23]

PALMER, Francis Beaufort was born on July 7, 1845. Son of Reverend William Palmer (one of the originators of the Oxford Movement) and Sophia, daughter of Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort, Knight Commander of the Bath, Fellow of the Royal Society.

-- Francis Beaufort Palmer, by prabook.com

Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer, youngest son

Ancestors

1. Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer (Mason)

2. Sir Francis V. Beaufort Palmer 1845 - ante 1941

3. Rev. William Palmer (Beaufort) 1803 - post 1881

-- Francis Napier Beaufort-Palmer, youngest son, by genealogy.org

• Emily Anne Smythe (1826–1887) was a hero of Bulgaria, a writer, illustrator and advocate of change in the training of nurses.[24]

Lady Strangford, Emily Ann Smythe or Emily Anne Beaufort (1826 – 24 March 1887) was a British illustrator, writer and nurse. There are streets named after her and permanent museum exhibits about her in Bulgaria. She established hospitals and mills to assist the Bulgarians following the April Uprising in 1876 that preceded the re-establishment of Bulgaria. She was awarded the Royal Red Cross medal by Queen Victoria for establishing another hospital in Cairo....

In 1858 she set out on a journey with her elder sister to Egypt. The book that she wrote, Egyptian Sepulchres and Syrian Shrines was dedicated to her sister, and describes the places she visited in Syria, Lebanon, Asia Minor and Egypt with beautiful illustrations based on her sketches from her journey. The volume was so popular that it was re-issued several times.

Of the ancient oasis city, Palmyra she writes:

"I was once asked whether Palmyra was "not a broken-down old thing in a style of slovenly decadence?" It is true its style is neither pure nor severe: nothing over which the lavish hand of hasty and Imperial Rome has passed is ever so: but, Tadmor [Palmyra] is free from all the vulgarity of real decadence; it is so entirely irregular as to be sometimes fantastic; the designs are overflowing with richness and fancy, but it is never heavy: it is free, independent, bizarre, but never ungraceful; grand indeed, though hardly sublime, it is almost always bewitchingly beautiful." (pp. 239–40)

Color lithograph panorama of Palmyra, Syria by Nicholas Hanhart after Emily Anne Beaufort Smythe, 1862.

Egyptian Sepulchres and Syrian Shrines by Beaufort

Strangford received a critical review of her 1861 book Egyptian Sepulchres and Syrian Shrines by Percy Smythe, later Viscount Strangford. Unusually, this led to them meeting and their marriage.

Percy Ellen Algernon Frederick William Sydney Smythe, 8th Viscount Strangford (26 November 1825 – 9 January 1869) was a British nobleman and man of letters.

He was born in St Petersburg, Russia, the son of the 6th Viscount Strangford, the British Ambassador, Ottoman Turkey, Sweden, and Portugal. During all his earlier years Percy Smythe was nearly blind, in consequence, it was believed, of his mother having suffered very great hardships on a journey up the Baltic Sea in wintry weather shortly before his birth.

His education began at Harrow School, whence he went to Merton College, Oxford. He excelled as a linguist, and was nominated by the vice-chancellor of Oxford in 1845 a student-attache at Constantinople.

While at Constantinople, where he served under Lord Stratford de Redcliffe, Smythe gained a mastery not only of Turkish and its dialects, but of almost every form of modern Greek, from the language of the literati of Athens to the least Hellenized Romaic. He had already a large knowledge both of Persian and Arabic before going east, but until his duties led him to study the past, present and future of the sultan's empire he had given no attention to the tongues which he well described as those of the international rabble in and around the Balkan peninsula.

On succeeding his brother as Viscount Strangford in 1857 he continued to live in Constantinople, immersed in cultural studies. At length, however, he returned to England and wrote a good deal, sometimes in the Saturday Review, sometimes in the Quarterly Review, and much in the Pall Mall Gazette. A rather severe review in the first of these organs of the Egyptian Sepulchres and Syrian Shrines of Emily Anne Beaufort (1826–1887) led to a result not very usual, the marriage of the reviewer and the author.

One of the most interesting papers Lord Strangford ever wrote was the last chapter in his wife's book on the Eastern Shores of the Adriatic. That chapter was entitled "Chaos," and was the first of his writings which made him widely known amongst careful students of foreign politics. From that time forward everything that he wrote was watched with intense interest, and even when it was anonymous there was not the slightest difficulty in recognising his style, for it was unlike any other.

Percy Smythe was president of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1861–64 and 1867–69.

-- Percy Smythe, 8th Viscount Strangford, by Wikipedia

In 1859 and 1860 she was travelling in Smyrna, Rhodes, Mersin, Tripoli, Beirut, Baalbek, Athens, Attica, the Pentelicus mountains, Constantinople and Belgrade. During the whole journey she kept a journal recording all that she experienced.

When Strangford published her second book Eastern Shores of the Adriatic in 1864 it had a final anonymous chapter title "Chaos," which is attributed to her husband, Percy Smythe, 8th Viscount Strangford. This work is considered important in his writing career. Her husband was twice president of the Royal Asiatic Society in the 1860s. He died in 1869 and as they had no children his titles became extinct.

Following her husband's death Strangford volunteered to serve as a nurse in (probably) University College Hospital in London. In 1874 her studies led her to advocate a change in the way that nurses were trained. She published Hospital Training for Ladies: an Appeal to the Hospital Boards in England. She advocated that nurses should be allowed to train and work part-time. She believed that the training to be a nurse would benefit many women in their role within a family. This idea did not gain official backing as the major objective at the time was to establish nursing as a profession and not as a part-time activity for amateurs.

The war crimes that were taking place in Bulgaria in 1876 gained her attention. Christians had suffered massacres by the Ottomans and Strangford initially joined one committee and then she set up her own. Thousands of pounds were raised by the Bulgarian Peasants Relief Fund and she went to Bulgaria in 1876 with Robert Jasper More, eight doctors and eight nurses. Both she and More wrote letters to The Times to report and gather more funds. Strangford believed that the Bulgarians and not the Serbs would be important as the Ottoman Empire shrank. These were views that she had shared with her husband. Strangford found the Bulgarians to just need the tools for their own self-improvement and she was impressed that their first priority was a school. She built a hospital at Batak and eventually other hospitals were built at Radilovo, Panagiurishte, Perushtitsa, Petrich and at Karlovo. She also provided subsidies to a flour mill and a number of saw mills.

In 1883 Queen Victoria awarded her the Royal Red Cross for creating, with Dr Herbert Sieveking the Victoria Hospital, Cairo. The hospital continued in operation thanks to a grant of £2,000 per year from the Egyptian government taking in local students for training and offering first class accommodation on a private basis.

Strangford edited A Selection from the Writings of Viscount Strangford on Political, Geographical and Social Subjects which she published in 1869 and Original Letters and Papers upon Philology and Kindred Subjects in 1878. She also published her brother-in-law's novel Angela Pisani after his death and she helped found the Women's Emigration Society with Caroline Blanchard which arranged for British women to find jobs abroad.

In her later years, Lady Strangford had a London home at 3 Upper Brook Street, Mayfair. She died on board SS Lusitania of a stroke in 1887. She was travelling through the Mediterranean en route for Port Said where she was to create a hospital for seamen. Her body was returned to London and buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.[2]

-- Lady Strangford, by Wikipedia

Beaufort married again in 1838, to Honora Edgeworth, the daughter of his brother-in-law Richard Lovell Edgeworth and his second wife. (Francis' sister Frances Beaufort had married Edgeworth as his fourth wife years earlier in the 1810s.)

Legacy

Wind force scale

Main article: Beaufort scale

During these early years of command, Beaufort developed the first versions of his Wind Force Scale and Weather Notation coding, which he was to use in his journals for the remainder of his life. From the circle representing a weather station, a staff (rather like the stem of a note in musical notation) extends, with one or more half or whole barbs. For example, a stave with 3½ barbs represents Beaufort seven on the scale, decoded as 32–38 mph, or a "moderate Gale".

Geographical legacy

Beaufort, like other patrons of exploration, has had his name given to many geographical places. Among these:

• Beaufort Sea (arm of Arctic Ocean)

• Beaufort Island, Antarctic

Cryptographic legacy

Beaufort created the Beaufort cipher. It is a substitution cipher similar to the Vigenère cipher.

References

1. Mollan, R Charles (2002). Irish Innovators. Royal Irish Academy. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-874045-88-5.

2. "A new map of Ireland : civil and ecclesiastical". Library of Congress. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

3. Alfred Friendly, Beaufort of the Admiralty, Hutchinson, 1977

4. Image:BeaufortTomb.JPG

5. Marshall, John (1828). Royal naval biography; or, Memoirs of the services of all the flag-officers, superannuated Rear-Admirals, Retired Captains, Post Captains and Commanders whose names appeared on the Admiralty list of Sea-Officers of the year 1823, or who have since been promoted. Supplement Part II. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown and Geen. pp. 82–94.

6. John de Courcy Ireland. "Francis Beaufort (Wind Scale)". On-line Journal of Research on Irish Maritime History. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

7. Courtenay, Nicholas (2002). "8". Gale Force 10 – The life and legacy of Admiral Beaufort. Review.

8. Beaufort, Francis (1817). Karamania, Or A Brief Description Of The South Coast Of Asia Minor. London: R. Hunter.

9. Hume, Robert (17 March 2014). "Why wind guru Beaufort had to hide a stormy personal life". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

10. Ritchie, G.S. (1967). The Admiralty Chart. London: Hollis & Carter.

11. Ross, W.Gillies (2004). "The Admiralty and the Franklin search". The Polar Record. 40 (4): 289–301. doi:10.1017/S003224740400378X.

12. John Frederick William Herschel (1849). A Manual of Scientific Enquiry: Prepared for the Use of Her Majesty's Navy : and Adapted for Travellers in General. J. Murray.

13. Doodson, Arthur Thomas; Warburg, Harold Dreyer (1941). Admiralty Manual of Tides. H.M. Stationery Office. pp. 137–138. ISBN 978-0-7077-2124-8.

14. Warburg, H.D. (1919). "The Admiralty Tide Tables and North Sea Tidal Predictions". The Geographical Journal. 63 (5): 308–326. JSTOR 1779472.

15. Morris, Roger (November 1996). "Two hundred years of Admiralty charts and surveys". The Mariner's Mirror. 82 (4): 426. doi:10.1080/00253359.1996.10656616.

16. "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

17. "Francis Beaufort Blue Plaque". openplaques.org. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

18. Rodger, N. A. M. "Beaufort, Sir Francis". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1857. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

19. Royal Society (1857). Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Taylor & Francis. p. 526.

20. "Beaufort, Daniel Augustus (BFRT831DA)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

21. Lodge's Peerage and Baronetage (knightage & Companionage) of the British Empire. Hurst & Blackett. 1861. p. 685.

22. "Beaufort, Francis Lestock (BFRT831FL)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

23. Walford, Edward (1869). The County Families of the United Kingdom Or, Royal Manual of the Titled and Untitled Aristocracy of Great Britain and Ireland. R. Hardwicke. p. 752.

24. Baigent, Elizabeth. "Smythe, Emily Anne, Viscountess Strangford (bap. 1826, d. 1887)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25963. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

Further reading

• Webb, Alfred (1878). "Beaufort, Sir Francis" . A Compendium of Irish Biography. Dublin: M. H. Gill & son.

• Alfred Friendly. Beaufort of the Admiralty. Random House, New York, 1973.

• Nicholas Courtney. "Gale Force 10, the life and legacy of Admiral Beaufort". London: Review. 2002.

• Huler, Scott (2004). Defining the Wind: The Beaufort Scale, and How a 19th-Century Admiral Turned Science into Poetry. Crown. ISBN 1-4000-4884-2.

• Laughton, John Knox (1885). "Beaufort, Francis" . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. 04. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

• Laughton, John Knox; Rodger, Nicholas (2008) [2004]. "Beaufort, Francis". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1857. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

• Works by Francis Beaufort at Open Library

• Works by or about Francis Beaufort at Internet Archive

• Works by or about Francis Beaufort in libraries (WorldCat catalog)