by A.L. Basham

Proceedings of the Indian History Congress

Vol. 14, pp. 37-41

1951

In the light of these researches, peering down the dark vistas of the past, we see that at the time of Buddha's visit, referred to in the above-quoted lines, — that is, somewhere between the fourth and fifth centuries before our era — Pataliputra was a small village on the south bank of the Ganges, and it was being fortified by the king of Rajagrha (Rajgir) as a post from which he might conquer the adjoining provinces and petty republics across the river.

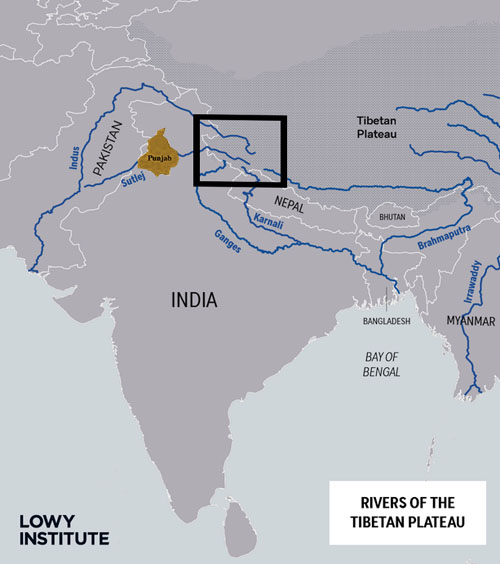

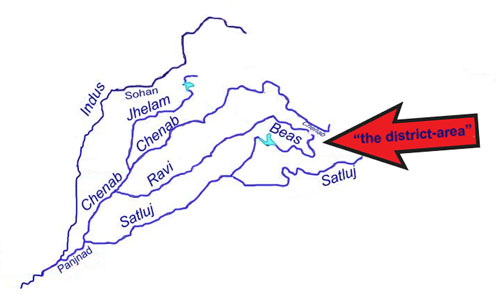

Standing at a point of such great commercial and strategical importance, at or near the confluence of all the five great rivers of Mid-India, namely, the Ganges, the Gogra, the Rapti, the Gandak, and the Son, as seen in the accompanying map, and commanding the traffic of these great water-ways of the richest part of India, it quickly grew into a great city, as was predicted.

Within about one generation after Buddha's visit the new monarch left the old stronghold of Rajgir, on the eastern edge of the highlands of Central India, overlooking the rich Ganges Valley, and one of the hilly fastnesses to which the vigorous invading Aryans fondly clung, and transferred his seat of government out to the new city in the centre of the plain. Thus when the conquest of all the adjoining and upper provinces welded India for the first time into one great dominion, Pataliputra became the capital of that vast empire.

-- Report on the Excavations At Pataliputra (Patna): The Palibothra of the Greeks, by L.A. Waddell

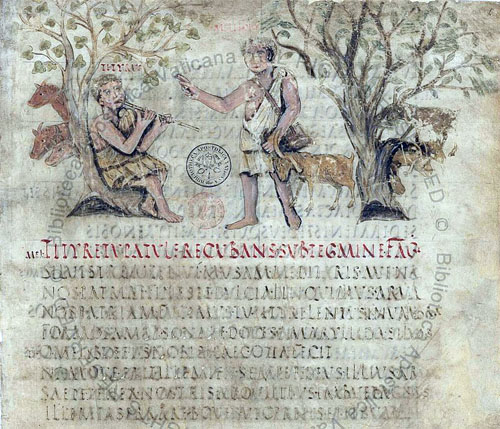

Mahaparinibbana-Sutta...

Reasons have been advanced by the translator of the Mahaparinibanna-Sutta for holding that the work cannot well have been composed very much later than the fourth century B.C. And, in the other direction, he has claimed that substantially, as to not only ideas but also words, it can be dated approximately in the fifth century. That would tend to place the composition of its narrative within eight decades after the death of Buddha, for which event B.C. 482 seems to me the most probable and satisfactory date that we are likely to obtain. In view, however, of a certain prophecy which is placed by the Sutta in the mouth of Buddha, it does not appear likely that the work can be referred to quite so early a time as that.

In the course of his last journey, Buddha came to the village Pataligama. At that time, we know from the commencement of the work, there was war, or a prospect of war, between Ajatasatta, king of Magadha, and the Vajji people. And, when Buddha was on this occasion at Pataligama, Sunidha and Vassakara, the Mahamattas or high ministers for Magadha, were laying out a regular city (nagara) at Pataligama, in order to ward off the Vajjis. The place was haunted by many thousands of “fairies” (devata), who inhabited the plots of ground there. And it was by that spiritual influence that Sunidha and Vassakara had been led to select the site for the foundation of a city; the text says: “Wherever ground is so occupied by powerful fairies, they bend the hearts of the most powerful kings and ministers to build dwelling-places there, and fairies of middling and inferior power bend in a similar way the hearts of middling or inferior kings and ministers.” Buddha with his supernatural clear sight beheld the fairies. And, remarking to his companion, the venerable Ananda, that Sunidha and Vassakara were acting just as if they had taken counsel with the Tavatimsa “angels” (deva), he said: -- “Inasmuch, O Ananda!, as it is an honourable place as well as a resort of merchants, this shall become a leading city, Pataliputta, a great trading centre; but, O Ananda!, three dangers will befall Pataliputta, either from fire, or from water, or from dissension.”

-- The Tradition about the Corporeal Relics of Buddha, by J. F. Fleet, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, (Jul., 1906), pp. 655-671 (17 pages)

In Magadha

1. Thus have I heard. Once the Blessed One dwelt at Rajagaha, on the hill called Vultures' Peak. At that time the king of Magadha, Ajatasattu, son of the Videhi queen, desired to wage war against the Vajjis. He spoke in this fashion: "These Vajjis, powerful and glorious as they are, I shall annihilate them, I shall make them perish, I shall utterly destroy them."

2. And Ajatasattu, the king of Magadha, addressed his chief minister, the brahman Vassakara, saying: "Come, brahman, go to the Blessed One, pay homage in my name at his feet, wish him good health, strength, ease, vigour, and comfort, and speak thus: 'O Lord, Ajatasattu, the king of Magadha, desires to wage war against the Vajjis. He has spoken in this fashion: "These Vajjis, powerful and glorious as they are, I shall annihilate them, I shall make them perish, I shall utterly destroy them."' And whatever the Blessed One should answer you, keep it well in mind and inform me; for Tathagatas do not speak falsely."

3. "Very well, sire," said the brahman Vassakara in assent to Ajatasattu, king of Magadha. And he ordered a large number of magnificent carriages to be made ready, mounted one himself, and accompanied by the rest, drove out to Rajagaha towards Vultures' Peak. He went by carriage as far as the carriage could go, then dismounting, he approached the Blessed One on foot. After exchanging courteous greetings with the Blessed One, together with many pleasant words, he sat down at one side and addressed the Blessed One thus: "Venerable Gotama, Ajatasattu, the king of Magadha, pays homage at the feet of the Venerable Gotama and wishes him good health, strength, ease, vigour, and comfort. He desires to wage war against the Vajjis, and he has spoken in this fashion: 'These Vajjis, powerful and glorious as they are, I shall annihilate them, I shall make them perish, I shall utterly destroy them.'"

Conditions of a Nation's Welfare

4. At that time the Venerable Ananda was standing behind the Blessed One, fanning him, and the Blessed One addressed the Venerable Ananda thus: "What have you heard, Ananda: do the Vajjis have frequent gatherings, and are their meetings well attended?"

"I have heard, Lord, that this is so."

"So long, Ananda, as this is the case, the growth of the Vajjis is to be expected, not their decline.

"What have you heard, Ananda: do the Vajjis assemble and disperse peacefully and attend to their affairs in concord?"

"I have heard, Lord, that they do."

"So long, Ananda, as this is the case, the growth of the Vajjis is to be expected, not their decline.

"What have you heard, Ananda: do the Vajjis neither enact new decrees nor abolish existing ones, but proceed in accordance with their ancient constitutions?"

"I have heard, Lord, that they do."

"So long, Ananda, as this is the case, the growth of the Vajjis is to be expected, not their decline.

"What have you heard, Ananda: do the Vajjis show respect, honor, esteem, and veneration towards their elders and think it worthwhile to listen to them?"

"I have heard, Lord, that they do."

"So long, Ananda, as this is the case, the growth of the Vajjis is to be expected, not their decline.

"What have you heard, Ananda: do the Vajjis refrain from abducting women and maidens of good families and from detaining them?"

"I have heard, Lord, that they refrain from doing so."

"So long, Ananda, as this is the case, the growth of the Vajjis is to be expected, not their decline.

"What have you heard, Ananda: do the Vajjis show respect, honor, esteem, and veneration towards their shrines, both those within the city and those outside it, and do not deprive them of the due offerings as given and made to them formerly?"

"I have heard, Lord, that they do venerate their shrines, and that they do not deprive them of their offerings."

"So long, Ananda, as this is the case, the growth of the Vajjis is to be expected, not their decline.

"What have you heard, Ananda: do the Vajjis duly protect and guard the arahats, so that those who have not come to the realm yet might do so, and those who have already come might live there in peace?"

"I have heard, Lord, that they do."

"So long, Ananda, as this is the case, the growth of the Vajjis is to be expected, not their decline."

5. And the Blessed One addressed the brahman Vassakara in these words: "Once, brahman, I dwelt at Vesali, at the Sarandada shrine, and there it was that I taught the Vajjis these seven conditions leading to (a nation's) welfare. So long, brahman, as these endure among the Vajjis, and the Vajjis are known for it, their growth is to be expected, not their decline."

Thereupon the brahman Vassakara spoke thus to the Blessed One: "If the Vajjis, Venerable Gotama, were endowed with only one or another of these conditions leading to welfare, their growth would have to be expected, not their decline. What then of all the seven? No harm, indeed, can be done to the Vajjis in battle by Magadha's king, Ajatasattu, except through treachery or discord. Well, then, Venerable Gotama, we will take our leave, for we have much to perform, much work to do."

"Do as now seems fit to you, brahman." And the brahman Vassakara, the chief minister of Magadha, approving of the Blessed One's words and delighted by them, rose from his seat and departed....

26. At that time Sunidha and Vassakara, the chief ministers of Magadha, were building a fortress at Pataligama in defense against the Vajjis. And deities in large numbers, counted in thousands, had taken possession of sites at Pataligama. In the region where deities of great power prevailed, officials of great power were bent on constructing edifices; and where deities of medium power and lesser power prevailed, officials of medium and lesser power were bent on constructing edifices.

27. And the Blessed One saw with the heavenly eye, pure and transcending the faculty of men, the deities, counted in thousands, where they had taken possession of sites in Pataligama. And rising before the night was spent, towards dawn, the Blessed One addressed the Venerable Ananda thus: "Who is it, Ananda, that is erecting a city at Pataligama?"

"Sunidha and Vassakara, Lord, the chief ministers of Magadha, are building a fortress at Pataligama, in defence against the Vajjis."

-- Maha-parinibbana Sutta: Last Days of the Buddha, translated from the Pali by Sister Vajira & Francis Story

The Magadha-Vajji War was a conflict between the Haryanka dynasty of Magadha and the neighbouring Vajji confederacy which was led by the Licchavis. The conflict is remembered in both Buddhist and Jain traditions. The conflict ended in defeat for the Vajji confederacy and the Magadhans annexing their territory.

There are differing accounts between the Jain and Buddhist traditions as to how the war played out although both sides agree that the Magahdans were victorious and ended up conquering the region.

-- Magadha-Vajji war, by Wikipedia

Daffy Duck: "This is preposterous"

Contamination, in manuscript tradition, a blending whereby a single manuscript contains readings originating from different sources or different lines of tradition. In literature, contamination refers to a blending of legends or stories that results in new combinations of incident or in modifications of plot.

-- Contamination: Literature, by Encyclopedia Britannica

NOTE -- From considerations of time and space I have not given references to many of the better known facts. All are to be found in such well known works of reference as Dr. Malalasekera's Dictionary of Pali Proper Names and Dr. H.C. Raychaudhuri's Political History of Ancient India.

The war between the king of Magadha Ajatasattu and the confederacy of the Vajjis, of which the most important element was the tribe of the Licchavis of Vesali, must have made a great impression upon contemporary India, for it is remembered and described in some detail by the independent traditions both of the Buddhists and the Jains. It is scarcely necessary to summarise the Buddhist account, but we will do so for the sake of completeness. The story occurs in the Mahiparinibbana Sutta of the Digha Nikiya, and in Buddhaghosa's commentary thereon.

A certain river port half in Magadhan territory and half in that of the Vajjis, produced a mysterious scented substance which was much in demand. Ajatasattu claimed this stuff, but when be sent his men for it on one occasion he found that the Vajjis had anticipated him and had taken it all.1 [Sumangala Vilasini, ii, 516.] He vowed to extirpate the Vajjis root and branch, and his chief minister Vassakara went to the Buddha to enquire whether the project was feasible. This was the occasion of the famous pronouncement of the Buddha, which seems to me to bear every sign of being authentic -- as long as the Vajjis held together, had regular folk-moots, revered the ancestral shrines and respected their women they were invincible. These are evidently the words of one who had a great love for the more or less democratic constitution of the so-called republican tribes and deplored the passing of traditional virtues. Soon after his interview with Vassakara, Buddha went north on his last journey. As he crossed the Ganges with his followers he again met Vassakara, with another minister named Sunidha, supervising the construction of a fort at the village of Pataligama, and prophesied the future greatness of the site.2 [Digha Nikaya, ii. 72 ff.] Meanwhile Vassakara, thought of a scheme to weaken the Vajjis. He pretended to quarrel with Ajatasattu, and fled to Vesali in the guise of a refuge. He was given a position of trust in the council of the tribal chieftains, and made use of the position to sow discord among them. In this he was so successful that in three years they were completely divided among themselves. Then Vassakara sent a message to Ajatasattu that the time was ripe, and he occupied Veslali with very little fighting.3 [Sumangala Vilasini, ii, 522.]

The Jain story, like the Buddhist, has to be pieced together from various sources. In this summary I retain the Buddhist names of the kings of Magadha for convenience. There is of course no shadow of doubt that the Seniya and Kuniya of the Jains are the Bimbisara and Ajatasattu of the Pali scriptures. Bimbisara, according to the Nirayavalika Sutra, committed suicide in prison in order to save his usurping son of the sin of patricide. This story virtually confirms the Buddhist account of Ajatasattu's murder of his father. But even before his father's death the new king had repented of his evil courses. On hearing of the suicide he moved his court to Campa. But soon after he was again inspired to evil by a wicked queen, called by the common Jaina name of Padmavati. His younger brothers Halla and Vehalla possessed a splendid elephant and a wonderful jewelled necklace. These the queen coveted, and persuaded Ajatasattu to demand them. The princes, rather than give them up, fled to the court of their maternal grandfather Cetaka, the chieftain of the Licchavis of Vesali. Ajatasattu sent to Cetaka to demand the treasures. When they were refused he made war on the Licchavis and the Nirayavalika speaks of a great battle in which many of Ajatasattu's brothers were killed.4 [Nirayavalika Sutra, ed. A.S. Gopani and V.J. Chokshi, Ahmedabad, 1935, p. 19 ff.]

The story is continued by the Bhagavati Sutra, which speaks of two great battles. The first lasted ten days, and on each day the Magadhan army lost one of its generals, shot by Cetaka. On the eleventh day Ajatasattu threw in a secret weapon, presented to him by the god Indra himself -- a mahasilakantaka, which from its description seems to have been a great stone- thrower. This turned the scales. The second battle had a similar course, and Ajatasattu's fortunes were turned in the nick of time by another wonderful weapon, a chariot-club (ralthamusala), which caused great carnage.5 [Bhagavati Sutra, 3 vols., Bombay, 1918-21, sutra 299 ff.]

The story is carried yet further by the early medieval commentator Jinadasa Gani in his curni, to the Avasyaka Sutra. The ruling body of the confederacy, described here and elsewhere in the Jaina scriptures as the nine Licchavis, the nine Mallakis and the eighteen tribal chieftains (ganaraja) of Kasi and Kosala, broke up. The confederate chieftains went home, and Cetaka, forced to fight alone, retreated to Vesali, where he was besieged for twelve years. The Licchavis had [i]a living palladium in Kulapalaka, a famous ascetic whose piety and austerities rendered the city impregnable. But Ajatasattu lured him to break his vows by means of a beautiful prostitute, and so the city fell. Cetaka drowned himself in a well and the remnant of the Licchavis fled to Nepal.6 [Avasyaka Sutra with curni of Jinadasa Gani, 2 vols., Ratlam, 1928-9; vol. ii, p. 172 ff.]

The story, which is told very elliptically by Jinadasa, is expanded in a commentary to the Uttaradhyayana Siltra quoted in the Jain encyclopedia Abhidhana Rajendra.7 [Abhidhana Rajendra, vol. iii s.v. Kulavalaya.]

The two versions disagree in many important details, but certain facts are in agreement and it is possible to extract credible history from them. The Jaina account of a long and difficult war is indirectly confirmed by the Buddhist story. The result of the war was clearly much in doubt when Ajatasattu sent Vassakara to the Buddha to enquire as to his prospects of success. The fort on the Ganges was built specifically for defence and not attack. In the fragmentary opening paragraph of the Sarvastivadin Sanskrit version of the Mahaparinibbina Sutta, recently published by Prof. Waldschmidt, Ajatasattu uses the words vyasanam, disaster, and rddhams ca sphi(tam), rich and prosperous, in his rage against the Vajjis.8 [Berlin, 1950, p. 7.] The easy victory superficially indicated by the Buddhist story was evidently preceded by a period of protracted and difficult warfare.

The enemy of Ajatasattu was not a single one, but a confederation. The Vajjis of the Pali scriptures are explicitly stated to be such a confederation, but the phrase used by the Jains 'the nine Licchavis, the nine Mallakis, and the eighteen tribal chieftains of Kasi and Kosala', suggest a wider alliance than that of the eight local tribes under the leadership of the Licchavis who comprised the Vajjian confederation. This phrase has attracted the attention of Prof. H. C. Raychaudhuri, who suggests 'that all the enemies of Ajatasattu, including the rulers of Kasi-Kosala and Vaisali, offered combined resistance. The Kosalan war and the Vajjian war were probably not isolated events but parts of a common movement directed against the hegemony of Magadha'.9 [Political History of Ancient India, 5th edn., Calcutta 1950, p. 213.] The Kosalan war, that between Ajatasattu and his uncle Pasenadi of Kosala immediately on the former 's usurpation, is less well attested than that with the Vajjis, since it is mentioned in the Buddhist tradition only.10 [Samyutta Nikaya, tr., i., 109.] But the evidence of that tradition points to the fact that peace had been concluded between the two sides, and Pasenadi had been succeeded by his son Vidudabha and had died, before the war with the Vajjis. Raychaudhure's hypothesis does not explain how Kasi and Kosala, both of which had been controlled by Pasenadi, came to be ruled by eighteen tribal chieftains. For this reason it is difficult of acceptance as it stands. Even more improbable is a theory once suggested by Prof. B. M. Barua,11 [Indian Culture, ii. 810.] that the whole of the Kosalan kingdom was under the suzerainty of the Licchavis; this is contradicted by the whole of the Buddhist tradition and need not be considered further.

A possible explanation of the eighteen ganarajas of Kasi and Kosala would link them with Vidudabha's devastation of the Sakiyas, and his death soon afterwards. The motive given for Vidudabha's wanton attack on the tribe, that he was incensed at their duplicity in providing his father with a base born girl all a bride, is too fantastic to be easily credible. It may well be that the only motive of the new and ambitious king of Kosala was the desire to impose a tighter and more centralized control on the feudatory tribes to the north and east of his kingdom. But whatever his motive, such an attack might be expected to rouse the suspicion and hostility of other tribes tributory to Kosala, of which the Mallas were one. We have no reliable account of the fate of Vidudabha, but the Pali story that he was drowned immediately after his destruction of the Sakiyas12 [Dhammapada Commentary, i, 346 ff. 357 ff.] indicates at least that he did not long survive that event. It may well be that he was killed while trying to subdue other subordinate tribes in the eastern part of his kingdom. We suggest that these tribes, unwilling to accept Vidudaha's suzerainty and incensed at his destruction of the Sakiyas, took advantage of his death to throw off all allegiance, and allied themselves with the strongest tribal republic of the region, the Vajjis or Licchavis of Vesali.

Of the names given in the Jaina formula the nine Licchavis need no further definition. They are the chiefs of the Vajjian confederacy of the Pali scriptures. The nine Mallakis must surely be the Mallas, probably the most important of the Kosalan tribes formerly tributory to Pasenadi. The eighteen tribal chieftains of Kasi and Kosala are probably the leaders of lesser tribes, originally included within the Kosalan empire. We would agree with Raychaudhuri to this extent, that the accounts give evidence of a widespread league of the tribal peoples north of the Ganges, no doubt uneasy at the growing imperialist ambition of the new rulers of Kosala and Magadha, and determined to preserve their own constitutions and way of life, which they saw were seriously threatened.

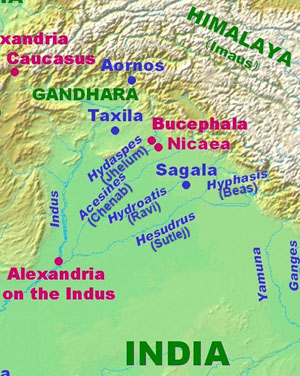

It is perhaps possible to trace a definite general policy followed throughout the reigns of Bimbisara and Ajatasattu, of which the Vajjian war was one phase. When Alexander reached the Seas he was told that all the Ganges-Yamuna basin was in the hands of a single king, Agrammes. The expansion of Magadha at the time of the Buddha was the first stage of the process which led to the empire of Asoka. It is hardly likely that Bimbisara and Ajatasattu ever visualized so mighty an empire, but they may have had the more liited objective of gaining control of as much of the Ganges river system as possible. It may be possible to trace the same objective later, motivating the campaigns of Samudra Gupta, Sasanka, and Dharmapala -- the king in possession of the lower course aiming at control of the whole river system. The importance of the rivers, in an India where population was smaller, roads were bad, and jungle more widespread, need hardly be emphasized.

Bimbisara's one annexation was Anga, with its wealthy river port of Campa, where, if we are to believe the Pali accounts, an already flourishing trade with the south brought gold jewels and spices. Campa must have served as an entrepot, from which southern luxury goods were distributed all over northern India. The acquisition of Amga was perhaps a necessary preliminary to the further expansion of Magadha, providing the wealth with which Bimbisara financed his policy of internal consolidation and Ajatasattu his aggressive wars. Of these the war with Kosala seems to have given Magadha control of a further length of the river, while from the war with the Vajjis she gained a foothold north of the Ganges, and thus controlled both banks. It is perhaps significant that according to the Buddhist story the latter war arose over a dispute in a river port which was half controlled by Ajatasattu and half by the Vajjis.

Both in internal and external policy Magadha under Bimbisra and Ajatasattu seems to have transcended earlier Indian conceptions of statecraft. It is possible, and I believe reasonably probable, that some inspiration for these new developments in ancient Indian polity came from the west. It may be more than a coincidence that while Bimbisara was a young man Cyrus was building up the greatest empire the world had yet seen. Before Ajatasattu's usurpation Achaemenid power extended to the Indus, if not beyond, and Taksasila seems to have been annexed. Bimbisara had been in diplomatic contact with Pukkusati, the king of Takasila. A busy caravan route led from Magadha to the north-west, and young men of the two upper classes would go from the Ganges valley to Taksasila to finish their education. It seems very unlikely that the two energetic king of Magadha should have been unaware of what was happening on the north-western borders of India. With the increased wealth at their disposal as a result of their control of trade at the eastern gate of Aryan India they may well have been inspired in their policy of expansion by what they heard of Persian affairs.

One further point deserves consideration -- the wonderful weapons with which, according to the Jain story, Ajatasattu successfully decided his two battles with Licchavis. The 'mahasilakantaka' evidently suggests a catapult, and the 'rathamusala' a battering ram. In the acceptance of the historicity of the latter weapon there is no difficulty once allowance has been made for the exaggerations to which Jain writers were so inclined. The catapult is more difficult however. Battering rams, siege towers, and other large war-engines were used by the Babylonians and Persians, and there is no reason why Ajatasattu should not also have used them. But we have no record of the use of war-engines for the discharge of large missiles in Asia until the days of Alexander, with one dubious exception. The exception occurs in the Old Testament, in the 2nd Book of Chronicles (xxvi, 15), where it is stated that king Uzziah of Judah, in the 7th century B.C., defended Jerusalem with engines which discharged great stones. If it could be shown that some form of catapult was even occasionally used in the Middle East the acceptance of Ajatasattu's mahasilakantaka would be much easier. But the Book of Chronicles is generally thought to have been compiled at a comparatively late date, and Professor Sidney Smith, with whom I have discussed the matter, believes that Uzziah's catapults are almost certainly the false attribution of a much later writer, to whom catapults were familiar. I am assured by Prof. Henning that there is no record of their being used by the Achaemenids.

This being the case we must either believe that catapults were invented independently in India at about the time of Ajatasattu, or that the wonderful weapon described by the Jain commentator is also a false attribution. On the strength of this one late reference I find it hard to accept the former alternative. The Jaina story, read in conjunction with Pali references, may, however, be taken to indicate that as in civil so in military affairs the Magadha of Bimbisara and Ajatasattu outstripped its contemporaries. The foundation was laid by the peaceful Bimbisara and the aggressive Ajatasattu of the first united India, and the fact that Bharat at the present day is a single republic and not an aggregate of warring petty states must in some measure be ultimately due to the progressive policies of these two energetic kings of 2,500 years ago.