from various sources

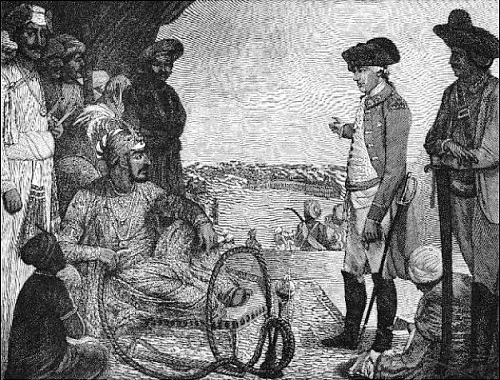

Of the commodities collected for the European market, that part, the acquisition of which was attended with the greatest variety of operations, was the produce of the loom. The weavers, like the other laborious classes of India, are in the lowest stage of poverty, being always reduced to the bare means of the most scanty subsistence. They must at all times, therefore, be furnished with the materials of their work, or the means of purchasing them; and with subsistence while the piece is under their hands. To transact in this manner with each particular weaver, to watch him that he may not sell the fabric which his employer has enabled him to produce, and to provide a large supply, is a work of infinite detail, and gives employment to a multitude of agents. The European functionary, who, in each district, is the head of as much business as it is supposed that he can superintend, has first his banyan, or native secretary, through whom the whole of the business is conducted: The banyan hires a species of broker, called a gomastah, at so much a month: The gomastah repairs to the aurung, or manufacturing town, which is assigned as his station; and there fixes upon a habitation, which he calls his cutchery: He is provided with a sufficient number of peons, a sort of armed servants; and hircarahs, messengers or letter carriers, by his employer: These he immediately dispatches about the place, to summon to him the dallâls, pycârs and weavers: The dallâls and pycârs are two sets of brokers; of whom the pycârs are the lowest, transacting the business of detail with the weavers; the dallâls again transact with the pycârs; the gomastah transacts with the dallâls, the banyan with the gomastah, and the Company’s European servant with the banyan. The Company’s servant is thus five removes from the workman; and it may easily be supposed that much collusion and trick, that much of fraud towards the Company, and much of oppression towards the weaver, is the consequence of the obscurity which so much complication implies.

-- The History of British India, vol. 3 of 6, by James Mill

Peons: Infantry.

-- India Tracts, by Mr. J.Z. Holwell, and Friends.

... eighteenth century in Bengal, peon had become a derogatory term for a matchlockman [A soldier armed with a matchlock gun], such as those found in the local sebundi (revenue collector's militia).

-- Culture, Combat, and Colonialism in Eighteenth-and Nineteenth-Century India, by Randolf G. S. Cooper, The International History Review, XXVII. 3: September 2005, pp. 473-708

Gomastha (also spelled Gumastha or Gumasta, Persian: agent) described an Indian agent of the British East India Company employed in the Company's colonies, to sign bonds, usually compellingly, by local weavers and artisans to deliver goods to the Company. The prices of the goods were fixed by the gomasthas. The goods were exported by the Company to Europe. Earlier supply merchants very often lived within the weaving village, and had a close relationship with the weavers, looking after their needs and helping them in times of crisis. The new gomasthas were outsiders with no long-term social link with the village. They acted arrogantly, marched into villages with sepoys and peons, and punished weavers for delays. The weavers thus lost the space to bargain and sell to different buyers; the price they received from the Company was miserably low and the loans they had accepted tied them to the Company.

-- Gomastha, by Wikipedia

Holwell informed the Council in Calcutta on 6 May 1754 that as the Charter of 1753 had “put a stop to the application of Indian natives to the Mayor's Court in disputes among themselves" they had begun to follow the practice of assigning over their notes or bonds to European, Portuguese or Armenian inhabitants of Calcutta, which in his opinion was against the true “intent and meaning” of the said Charter and prejudiced the Company’s 'etlack' ["Under the Mohammadan government, fees paid by suitors on the decision of their causes; also a fee exacted from a defendant as wages for a peon stationed over him as soon as a complaint was preferred against him". Wilson A Glossary of Judicial and Revenue Terms, p. 346.] (itlaq) and commission....

The Armenians had established their first settlement in Bengal at Saidabad near Murshidabad in 1665, on the strength of a Mughal imperial farman, and since then they had trading concerns in different parts of the province. In 1748 two vessels of the Armenians, on their way to Bengal from [illegible] and Basra, were captured by the English. The Armenians appealed to Nawab Alivardi for redress whereupon the latter “ordered Peons on all their (English) Gomastahs at the Aurungs and stopped the boats which were bringing down their goods’’. [ Long, Selections from Unpublished Records, I, p. 12.]

-- Fort William-India House Correspondence and Other Contemporary Papers Relating Thereto, Vol. I: 1748-1756, Edited by K. K. Datta, M.A., Ph.D., Professor of History, Patna University, Patna

The Calcutta court was not much of a success during the first fifty years of its existence. This is apparent from a discussion on its reform in 1802. [Notes on the defects or the court of requests at Calcutta, by Sir John Austruther, Chief Justice of the Calcutta Supreme Court, Bengal Civil Judicial Consultations, 18 March 1802, No. 12.] The fundamental defect of the court as formed in 1753, arose out of its constitution by unpaid commissioners. The court's sittings were extremely laborious and prolonged, often stretching up to five hours a day. It made the commissioners reluctant to undertake this exertion for which no monetary compensation was to be had. As a result, in spite of there-being twenty-four commissioners on roll, it was always found difficult even to secure the attendance of three, the minimum required to constitute the quorum. It was only by making personal approaches to some of the younger commissioners of his acquaintance that the clerk of the court was able to procure the minimum attendance necessary to form the court. [Ibid.]

As such, commissioners who were employed otherwise by the company were unable to spare enough time for the court's business, the court gradually came to be constituted by old civilians out of employment or by young Englishmen who never had any. Devotion or responsibility towards the business of the court could be expected from neither.

Out of the irregularity and laxity in the procedure of the court arose enormous abuses which rendered it more an instrument of fraud and exploitation, than that of justice. [Ibid.] The peons, amlas and clerks of the court found it easy to indulge in all sorts of corrupt practices, much to the harassment of the parties trying to seek redress from the court. Among the many malpractices prevailing in the court that Austruther listed, were:[T]hat many (defendants) complained that actions were brought and decrees passed against them, of which they had no notice, and by plaintiffs of whom they had never heard; others (complained) that they had attended their cause from day to day to no purpose, but the instant they were gone, the decree (was) passed against them: ... still others (complained) that the causes were (actually) decided by the Amlas after the Commissioners had gone; and that nothing was to be done without bribing the peons or their mates; that summons were issued in the names of fictitious plaintiffs, which were left in the hands of the peons for an indefinite time and were used as a means for harassing persons with names similar to that of the supposed defendants, ... and that the summons contained no definite time for appearance, with the result that the party had to keep attending every day ..., till their cause was called out by the native officers of the Court, who in fictitious suits (brought either by themselves or with their connivance), always cared to have the decree passed in the absence of the defendant. [Ibid.]

Coleman, the clerk of the court, informed Austruther, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Calcutta, that of an average of about 3,000 causes instituted monthly over the preceding four years, at least one third had been entirely fictitious. [Ibid.]

The plaintiffs, on the other hand, complained that the court's decrees were of no avail, because either they were not executed in consequence of the bribe given to the peons by the debtors, or, if they were, the money obtained was fraudulently appropriated by the vakeels and peons of the court. Thus, Austruther observed:When the amount was paid into the Court, nothing was more common than for the Vakeels to impersonate the real plaintiff and receive the money, and when the real plaintiff came, the amlas were always ready to swear that they were (sic) witness to the receipt (of the decreed amount by the plaintiff) ...... [Ibid.]

-- Evolution of the Small Cause Courts in India -- 1753-1887 with Special Reference to the Presidency Court at Calcutta, by Chittaranjan Sinha, M.A., B.L. (Patna), Ph.D. (Lond.).

In regard to the double fraud and exorbitant charge of repairing the roads, I have ready to lay before this Board the Banian's books, employed on this service, and the Head Peon attending him....

The 15th, Gosebeg Jemmautdaar complained to me, that he had not received a Cowrie of the wages due to him and ten Peons, that were placed as a guard at Govindpoor Gunge in March last, to look after the rice. Recollecting a charge of this kind, I turned to that month's account revenues, and found the Company debted for Rs. 232 / 10 for this service, account 20 Buckerserrias and two Ponsoys, whereas there were in truth only the Peons above mentioned, and 10 of the Company's Buckserrias from the different Chowkeys on board the Ponsways, and the expense of the Ponsways I find was paid by Moideb Huzzarah; and though the charge is continued to the Company for two months and four days, yet they were actually no longer on this service than one month and seven days, -- as Gosebeg, Sowanny, Ponswaar, and Lallmun Mangu, are now in waiting to prove...

The article Moorianoes, I believe, may need some explanation, as introductory to my observation on it. On every complaint where a Peon is ordered, he receives from the delinquent or defendant three punds of Cowries a day, one pund of which he keeps to himself, one pund 14 gundas belongs to the Company under the head of Etlack, and the remaining six gundas is daily collected apart, out of which the Etlack Mories or writers, are paid their wages, and the over-plus remains to the Company...

Under your Honor's, &c. influence and orders, the intentions of our Honorable Masters as set forth in their second paragraph, are already in part put in execution. The farms have been sold at public outcry, agreeable to their instructions, and the poor are relieved by remitting six of the lowest farms, as producing little more to the Company than discredit. The season being now arrived for measuring the ground, my utmost care and attention shall be employed in putting our Honorable Masters orders on that head in execution. In conformity to your Honor, &c. orders, I have made the strictest scrutiny into the several charges of Banians, writers, and other servants of the Cutcherry, under the denomination of Pikes, Peons, and Buckserries; also the charge of Chowkey Boats; and for the reduction made in these articles, I refer you to the several monthly accounts revenues for July, August, September and October, ready to be laid before you, as soon as the months of May and June are passed in council...

Though I have already explained what is meant by that branch of the revenues called Etlack, in my address to your Honor, &c. under date the 17th of August, 1752, I yet think it necessary to repeat here what I then said on the subject, that in this work every article of the revenues may have due regard paid to it. On every complaint registered in the Cutcherry, a Peon is ordered on the defendant, in cases of debt; or on the delinquent, in case of assaults, or other abuses. The Peon receives three Punds of Cowries per diem, one Pund, fourteen Gundas of which are brought to the credit of the Company, under the head of Etlack: one Pund is the Peon's fee, and the remaining six Gundas were set apart; out of which the Etlack Moories, or writers, were paid their wages; and the overplus, called Mooriannoes, sequestered to uses I am a stranger to. The article of Etlack has always been a heavy tax on the poor, from whom it has chiefly been collected, whilst those who could by any means obtain favor were excused, though well able to pay it. The contrary method I have pursued, as much as possible; and your Honor, &c. will observe in the Zemindary, how frequent occasions I meet with to remit this fee to the poor, as well to those who are released from the prisons, as those whose disputes are determined without imprisonment. The Cutcherry prison Etlack fees, and Catwall prison Etlack fees, amount each to three Punds of Cowries per diem, from each prisoner; the whole of which is brought to credit. The Etlack fees have, by some Zemindars, been raised to four Punds per diem, and by others reduced to two, the present establishment appears to me the most eligible medium, as the former would be a very heavy oppression on the poor, and the latter would too much tend to keep up that litigious spirit in the people, which possibly is not equaled by any race existing. What injury the Company may have sustained in this branch, I shall submit to your Honor, &c. judgment, by the following abstracts of the former and present credits....

How consistent the Suba has been in his adherence to this last counsel of his grandfather, we have woefully felt; but that we were not solely the objects of his resentment and designs, is evident: His perwanah to the French was dispatched the same day with ours: When he marched against us, he sent perwanahs to both French and Dutch, with orders to provide, and join him with ships, men, and ammunition, to attack us by water, whilst he attacked us by land: They refused; in consequence of their refusal, he invested their several forts and factories, and demanded an exorbitant sum from each. The French were glad to accommodate matters for the payment of three Lack and half of Rupees; the Dutch for four Lack and half, after having had, for a day and half, a body of the Suba's troops in their settlement, waiting orders to attack it; and a man stationed with an ax in his hands, to cut down their flag-staff and colors. The French had not money to pay the mulct laid on them, but gained Roy Doolob to become their security: The Dutch were reduced to immediate payment; and both did then, and ever since have been obliged to endure the most audacious and exasperating insults, from the lowest Peon in the service of the government.

-- Important Facts regarding the East India Company's Affairs in Bengal, from the Year 1752 to 1760. This Treatise Contains an Exact State of the Company's Revenues in that Settlement; With Copies of several very interesting Letters Showing Particularly, The Real Causes Which Drew on the Presidency of Bengal the Dreadful Catastrophe of the Year 1767; and Vindicating the Character of Mr. Holwell From Many Scandalous Aspersions Unjustly Thrown Out Against Him, in an Anonymous Pamphlet, Published March 6th, 1764, Entitled, "Reflections on the Present State of Our East-India Affairs.", from India Tracts, by Mr. J.Z. Holwell, and Friends.

The zamindars too adopted drastic steps against their rytos for arrears by sending piadas or peons who either seized the ryots' effects or confined or even flogged them....

The management of so vast a zamindari as Rajshahi would have been in itself a Herculean task, even had all gone smoothly. But within a very short time of the implementation of the scheme, accusations and counter-accusations between the diwan and naibs on the one hand and the zamindari officials on the other piled up in the Council, each side accusing the other of violence and oppression. The ryots of Rajshahi also brought several allegations of extortion against Nandalal Roy and Pran Bose. In one of their petitions to the Council, on 28 April, 1778 they alleged that the two naibs had exacted considerable sums, over and above the revenue dues, and had employed armed peons in the mufassil to plunder their effects and subject them to torture. As a result cultivation had almost stopped in several parganahs, for no fewer than four thousand families had been forced to run away to neighbouring districts. These irregularities were brought to the notice of the Provincial Council but without effect. They also represented their distress to the Diwan of the Council Ganga Gobinda Singh with a request to redress their grievances. But the latter being the chief protector of Roy and Bose took no action. Failing to secure justice, the peasants marched to Calcutta to lay their grievances personally before the Council. They concluded: "Your petitioners being poor and helpless inhabitants, utterly ruined, under the yoke of the said zilladers, most humbly beg leave to lay their hardships before this Hon’ble Board, imploring justice and assistance." They requested the Council to examine the conduct of Nandalal and Pran Bose and restore such sums of money as they had unjustly extorted from them. Allegations were also received from the amils of different parganahs such as Kaliganj, Kussumby, Eusufshahi, Amrul and Pukhuria. They claimed that the zamindari servants and rebellious ryots, acting in collusion, had expelled many of them from their parganahs using such violence against the amil of Kuttermal that his life was in danger. In consequence, the collection of revenues had been greatly hampered. Hastings, who had ignored the petitions of the ryots, accepted the complaints of the amils. His displeasure with the Rani was further aggravated and he immediately warned her that if the revenues were affected by the obstruction of her servants she would be held responsible and her allowances would be forfeited to make up the Company's revenues.

-- The Land Revenue History of the Rajshahi Zamindari &1765-1793), by Abul Barakat Mahiuddin Mahmood

We at present learn from the newspaper that the government has dismissed him (the foujdar) from his situation, and on inquiry found that last year a Coonbee had murdered his niece for her ornaments, and was apprehended by the police peons, who put a stick up his anus for extorting confession, and that the government has decided that the foujdar had ordered to do this to the above Coonbee who died while in custody -- but we feel certain that the foujdar could not have ordered to the above effect because in the deceased prisoner's deposition which was taken down before the government authorities, no mention is made about the foujdar's orders, nor did the police peons who were tried and punished say anything in their depositions concerning the foujdar's orders for putting a stick up the prisoner's anus or for doing such other evil action...

Gunnoo was accused of taking the ornaments of his niece Syee, a young girl of five years, and then drowning her in a well. One witness's deposition testified that Gunnoo denied knowing the girl's whereabouts. However, when police peons 'gave him a slap on the turban, a silver suklee (chain) fell out -- on searching him other ornaments were found.' According to the witness, when asked about the girl again, Gunnoo pleaded that the ornaments must have been planted on him, and repeated that he did not know Syee's whereabouts. At this point in the public interrogation, the foujdar is said to have suggested that 'he (Gunnoo) is frightened in this crowd take him to one side and 'sumjao' him (make him understand.' Gunnoo was then taken into the cowshed of a prostitute, Lateeb, and tortured. Afterwards, he was led to the well outside the town in which the girl's body was found. There, Gunnoo confessed to the crime. He died in custody two days later, on August 13, 1854....

On one hand, the police were seen as belonging to the generic category of state servants and functionaries of the law, while on the other, the 'native' police were viewed as a special category of colonial subjects who were outside the law. This tension is revealed in the legal documents that circulated after the sessions court sentenced the six police peons who were accused of committing the torture and murder of Gunnoo to four years hard labour, four months in solitary confinement, and the first seven and last seven days of the month on a 'conjee' diet. (rice water or gruel) The court described the acts of these six men as 'atrocious' and truly outside the bounds of law. These crimes were therefore treated as renegade acts committed without the authority of a superior. For this reason, the foujdar himself was not named as a defendant in the case....

The possibility that the murder of Gunnoo was not simply the act of renegade police peons but perhaps a deliberately ordered, official act, moved this case onto a larger stage. For if Gunnoo's death was now not an aberration but a more general police practice, it would be necessary to conduct an inquiry into this practice on the highest levels...

Campbell went on to note that policemen above the rank of common peon often functioned as witnesses to crimes, which literally allowed the police to take the law into their own hands. In 1857, a member of the house of commons noted the popular conviction that 'dacoity is bad enough, but that the subsequent police inquiry is worse.' This had much to do with the fact that confessions in the presence of the police were seen as adequate for judicial indictment. Magistrates with a poor command over native languages were often unfamiliar with the customary and/or religious codes that regulated persons and communities. They found themselves relying on confessions taken by the police rather than conducting their own inquiries. This suggests that the police often acted in a de facto judicial capacity, taking confessions, deciding guilt, and punishing wrongdoers. This exposed the uncertain position of the police in the implementation of law: were they merely law's functionaries, or were they in fact producing the evidence that law courts relied upon in the dispensation of justice?...

How was the instance of torture itself to be believed when, as the petition noted, neither Gunnoo nor the police peons had initially said anything about it?...

Two of the police peons were related to Gunnoo, and were described as 'enraged' by Syee's murder.

-- Problems of Violence, States of Terror, by Anupama Rao