by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/3/21

Kanishka I

Kushan emperor

Gold coin of Kanishka. Greco-Bactrian legend: [x] Shaonanoshao Kanishki Koshano "King of Kings, Kanishka the Kushan". British Museum.

Reign: 2nd century (120-144)

Predecessor: Vima Kadphises

Successor: Huvishka

Born: c. 70, Kapisi

Died: 144 (aged 73-74)

Dynasty: Kushan dynasty

Religion: Buddhism

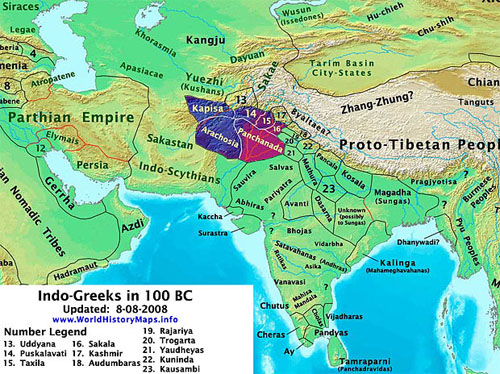

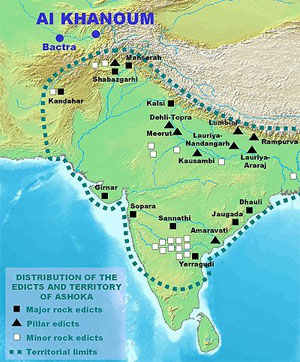

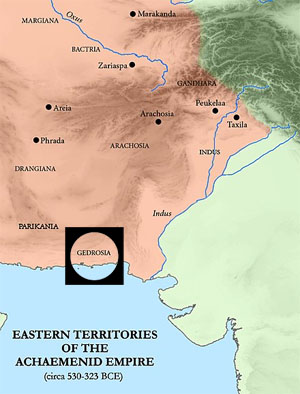

Kanishka I (Sanskrit: [x]; Greco-Bactrian: [x] Kanēške; Kharosthi: [x] Ka-ṇi-ṣka, Kaṇiṣka;[1] Brahmi: Kā-ṇi-ṣka), or Kanishka the Great, an emperor of the Kushan dynasty in the second century (c. 127–150 CE),[2] is famous for his military, political, and spiritual achievements. A descendant of Kujula Kadphises, founder of the Kushan empire, Kanishka came to rule an empire in Gandhara extending to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain. The main capital of his empire was located at Puruṣapura (Peshawar) in Gandhara, with another major capital at Kapisa. Coins of Kanishka were found in Tripuri (jabalpur madhya pradesh)

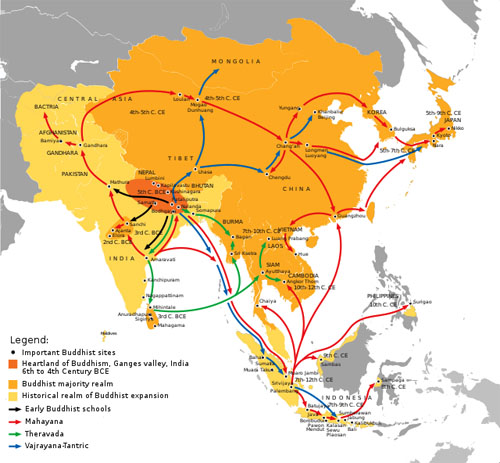

His conquests and patronage of Buddhism played an important role in the development of the Silk Road, and in the transmission of Mahayana Buddhism from Gandhara across the Karakoram range to China. Around 127 CE, he replaced Greek by Bactrian as the official language of administration in the empire.[3]

Earlier scholars believed that Kanishka ascended the Kushan throne in 78 CE, and that this date was used as the beginning of the Saka calendar era. However, historians no longer regard this date as that of Kanishka's accession. Falk estimates that Kanishka came to the throne in 127 CE.[4]

Genealogy

Mathura statue of Kanishka. The Kanishka statue in the Mathura Museum. There is a dedicatory inscription along the bottom of the coat.

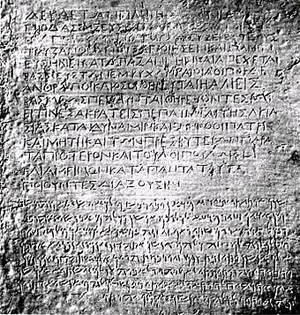

The inscription is in middle Brahmi script:

Mahārāja Rājadhirāja Devaputra Kāṇiṣka

"The Great King, King of Kings, Son of God, Kanishka".[5]

Mathura art, Mathura Museum

Kanishka was a Kushan of probable Yuezhi ethnicity.[6] His native language is unknown. The Rabatak inscription uses a Greek script, to write a language described as Arya (αρια) – most likely a form of Bactrian native to Ariana, which was an Eastern Iranian language of the Middle Iranian period.[7] However, this was likely adopted by the Kushans to facilitate communication with local subjects. It is not certain, what language the Kushan elite spoke among themselves.

Kanishka was the successor of Vima Kadphises, as demonstrated by an impressive genealogy of the Kushan kings, known as the Rabatak inscription.[8][9] The connection of Kanishka with other Kushan rulers is described in the Rabatak inscription as Kanishka makes the list of the kings who ruled up to his time: Kujula Kadphises as his great-grandfather, Vima Taktu as his grandfather, Vima Kadphises as his father, and himself Kanishka: "for King Kujula Kadphises (his) great grandfather, and for King Vima Taktu (his) grandfather, and for King Vima Kadphises (his) father, and *also for himself, King Kanishka".[10]

Conquests in South and Central Asia

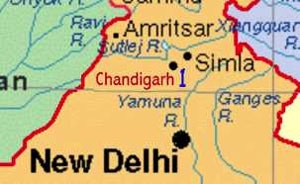

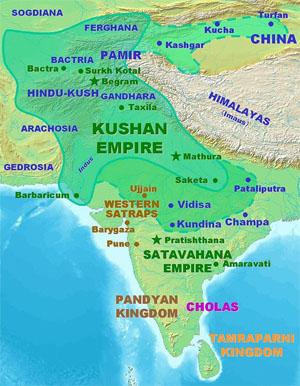

Kanishka's empire was certainly vast. It extended from southern Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, north of the Amu Darya (Oxus) in the north west to Northern India, as far as Mathura in the south east (the Rabatak inscription even claims he held Pataliputra and Sri Champa), and his territory also included Kashmir, where there was a town Kanishkapur (modern day Kanispora), named after him not far from the Baramula Pass and which still contains the base of a large stupa.

Knowledge of his hold over Central Asia is less well established. The Book of the Later Han, Hou Hanshu, states that general Ban Chao fought battles near Khotan with a Kushan army of 70,000 men led by an otherwise unknown Kushan viceroy named Xie (Chinese:[x]) in 90 AD. Ban Chao claimed to be victorious, forcing the Kushans to retreat by use of a scorched-earth policy. The territories of Kashgar, Khotan and Yarkand were Chinese dependencies in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang. Several coins of Kanishka have been found in the Tarim Basin.[11]

Controlling both the land (the Silk Road) and sea trade routes between South Asia and Rome seems to have been one of Kanishka's chief imperial goals.

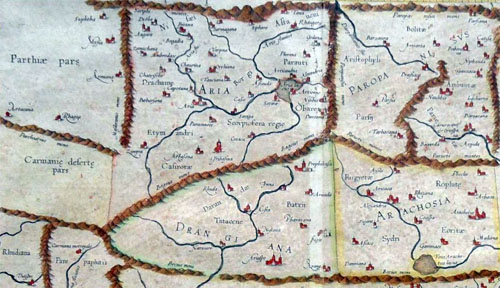

Kushan territories (full line) and maximum extent of Kushan dominions under Kanishka (dotted line), according to the Rabatak inscription.[12]

Probable statue of Kanishka, Surkh Kotal, 2nd century CE. Kabul Museum.[13]

Bronze coin of Kanishka, found in Khotan, modern China.

Samatata coinage of king Vira Jadamarah, in imitation of the Kushan coinage of Kanishka I. Bengal, circa 2nd-3rd century CE.[14]

Kanishka's coins

Kanishka's coins portray images of Indian, Greek, Iranian and even Sumero-Elamite divinities, demonstrating the religious syncretism in his beliefs. Kanishka's coins from the beginning of his reign bear legends in Greek language and script and depict Greek divinities. Later coins bear legends in Bactrian, the Iranian language that the Kushans evidently spoke, and Greek divinities were replaced by corresponding Iranian ones. All of Kanishka's coins – even ones with a legend in the Bactrian language – were written in a modified Greek script that had one additional glyph ([x]) to represent /[x]/ (sh), as in the word 'Kushan' and 'Kanishka'.

On his coins, the king is typically depicted as a bearded man in a long coat and trousers gathered at the ankle, with flames emanating from his shoulders. He wears large rounded boots, and is armed with a long sword as well as a lance. He is frequently seen to be making a sacrifice on a small altar. The lower halfIranian and Indic of a lifesize limestone relief of Kanishka similarly attired, with a stiff embroidered surplice beneath his coat and spurs attached to his boots under the light gathered folds of his trousers, survived in the Kabul Museum until it was destroyed by the Taliban.[15]

Hellenistic phase

Gold coin of Kanishka I with Greek legend and Hellenistic divinity Helios. (c. 120 AD).

Obverse: Kanishka standing, clad in heavy Kushan coat and long boots, flames emanating from shoulders, holding a standard in his left hand, and making a sacrifice over an altar. Greek legend [x]"[coin] of Kanishka, king of kings".

Reverse: Standing Helios in Hellenistic style, forming a benediction gesture with the right hand. Legend in Greek script: [x] Helios. Kanishka monogram (tamgha) to the left.

A few coins at the beginning of his reign have a legend in the Greek language and script: [x], basileus basileon kaneshkou "[coin] of Kanishka, king of kings."

Greek deities, with Greek names are represented on these early coins:

• [x] (ēlios, Hēlios), [x] (ēphaēstos, Hephaistos), [x] (salēnē, Selene), [x] (anēmos, Anemos)

The inscriptions in Greek are full of spelling and syntactical errors.

Iranian / Indic phase

Following the transition to the Bactrian language on coins, Iranian and Indic divinities replace the Greek ones:

• [x] (ardoxsho, Ashi Vanghuhi)

• [x] (lrooaspo, Drvaspa)

• [x] (adsho, Atar)

• [x] (pharro, personified khwarenah)

• ΜΑΟ (mao, Mah)

• [x], (mithro, miiro, mioro, miuro, variants of Mithra)

• [x] (mozdaooano, "Mazda the victorious?")

• ΝΑΝΑ, ΝΑΝΑΙΑ, [x] (variants of pan-Asiatic Nana, Sogdian nny, in a Zoroastrian context Aredvi Sura Anahita)

• [x] (manaobago, Vohu Manah )

• [x] (oado, Vata)

• [x] (orlagno, Verethragna)

Only a few Buddhist divinities were used as well:

• [x] (boddo, Buddha),

• [x] (shakamano boddho, Shakyamuni Buddha)

• [x] (metrago boddo, the bodhisattava Maitreya)

Only a few Hindu divinities were used as well:

[x] (oesho, Shiva). A recent study indicate that oesho may be Avestan Vayu conflated with Shiva.[16][17]

Kanishka and Buddhism

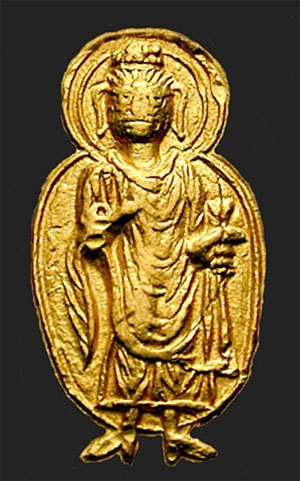

Gold coin of Kanishka I with a representation of the Buddha (c.120 AD).

Obv: Kanishka standing.., clad in heavy Kushan coat and long boots, flames emanating from shoulders, holding standard in his left hand, and making a sacrifice over an altar. Kushan-language legend in Greek script (with the addition of the Kushan [x] "sh" letter): [x] ("Shaonanoshao Kanishki Koshano"): "King of Kings, Kanishka the Kushan".

Rev: Standing Buddha in Hellenistic style, forming the gesture of "no fear" (abhaya mudra) with his right hand, and holding a pleat of his robe in his left hand. Legend in Greek script: [x] "Boddo", for the Buddha. Kanishka monogram (tamgha) to the right.

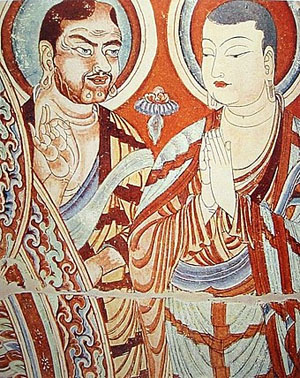

Kanishka's reputation in Buddhist tradition regarded with utmost importance as he not only believed in Buddhism but also encouraged its teachings as well. As a proof of it, he administered the 4th Buddhist Council in Kashmir as the head of the council. It was presided by Vasumitra and Ashwaghosha. Images of the Buddha based on 32 physical signs were made during his time.

He encouraged both Gandhara school of Greco-Buddhist Art and the Mathura school of Hindu art (an inescapable religious syncretism pervades Kushana rule). Kanishka personally seems to have embraced both Buddhism and the Persian attributes but he favored Buddhism more as it can be proven by his devotion to the Buddhist teachings and prayer styles depicted in various books related to kushan empire.

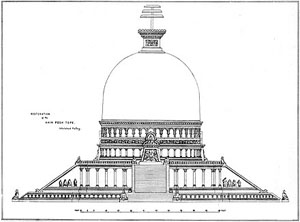

His greatest contribution to Buddhist architecture was the Kanishka stupa at Purushapura, modern day Peshawar. Archaeologists who rediscovered the base of it in 1908–1909 estimated that this stupa had a diameter of 286 feet (87 metres). Reports of Chinese pilgrims such as Xuanzang indicate that its height was 600 to 700 (Chinese) "feet" (= roughly 180–210 metres or 591–689 ft.) and was covered with jewels.[18] Certainly this immense multi-storied building ranks among the wonders of the ancient world.

Kanishka is said to have been particularly close to the Buddhist scholar Ashvaghosha, who became his religious advisor in his later years.

Buddhist coinage

The Buddhist coins of Kanishka are comparatively rare (well under one percent of all known coins of Kanishka). Several show Kanishka on the obverse and the Buddha standing on the reverse. A few also show the Shakyamuni Buddha and Maitreya. Like all coins of Kanishka, the design is rather rough and proportions tend to be imprecise; the image of the Buddha is often slightly overdone, with oversize ears and feet spread apart in the same fashion as the Kushan king.

Three types of Kanishka's Buddhist coins are known:

Standing Buddha

Depiction of the Buddha enveloped in a mandala in Kanishka's coinage. The mandorla is normally considered as a late evolution in Gandhara art.[19]

Only six Kushan coins of the Buddha are known in gold (the sixth one is the centerpiece of an ancient piece of jewellery, consisting of a Kanishka Buddha coin decorated with a ring of heart-shaped ruby stones). All these coins were minted in gold under Kanishka I, and are in two different denominations: a dinar of about 8 gm, roughly similar to a Roman aureus, and a quarter dinar of about 2 gm. (about the size of an obol).

The Buddha is represented wearing the monastic robe, the antaravasaka, the uttarasanga, and the overcoat sanghati.

The ears are extremely large and long, a symbolic exaggeration possibly rendered necessary by the small size of the coins, but otherwise visible in some later Gandharan statues of the Buddha typically dated to the 3rd–4th century CE (illustration, left). He has an abundant topknot covering the usnisha, often highly stylised in a curly or often globular manner, also visible on later Buddha statues of Gandhara.

In general, the representation of the Buddha on these coins is already highly symbolic, and quite distinct from the more naturalistic and Hellenistic images seen in early Gandhara sculptures. On several designs a mustache is apparent. The palm of his right hand bears the Chakra mark, and his brow bear the urna. An aureola, formed by one, two or three lines, surrounds him.

The full gown worn by the Buddha on the coins, covering both shoulders, suggests a Gandharan model rather than a Mathuran one.

"Shakyamuni Buddha"

Depictions of the "Shakyamuni Buddha" (with legend [x] "Shakamano Boddo") in Kanishka's coinage.

The Shakyamuni Buddha (with the legend "Sakamano Boudo", i.e. Shakamuni Buddha, another name for the historic Buddha Siddharta Gautama), standing to front, with left hand on hip and forming the abhaya mudra with the right hand. All these coins are in copper only, and usually rather worn.

The gown of the Shakyamuni Buddha is quite light compared to that on the coins in the name of Buddha, clearly showing the outline of the body, in a nearly transparent way. These are probably the first two layers of monastic clothing the antaravasaka and the uttarasanga. Also, his gown is folded over the left arm (rather than being held in the left hand as above), a feature only otherwise known in the Bimaran casket and suggestive of a scarf-like uttariya. He has an abundant topknot covering the ushnisha, and a simple or double halo, sometimes radiating, surrounds his head.

"Maitreya Buddha"

Depictions of "Maitreya" (with legend [x] "Metrago Boddo") in Kanishka's coinage.

The Bodhisattva Maitreya (with the legend "Metrago Boudo") cross-legged on a throne, holding a water pot, and also forming the Abhaya mudra. These coins are only known in copper and are quite worn out . On the clearest coins, Maitreya seems to be wearing the armbands of an Indian prince, a feature often seen on the statuary of Maitreya. The throne is decorated with small columns, suggesting that the coin representation of Maitreya was directly copied from pre-existing statuary with such well-known features.

The qualification of "Buddha" for Maitreya is inaccurate, as he is instead a Bodhisattva (he is the Buddha of the future).

The iconography of these three types is very different from that of the other deities depicted in Kanishka's coinage. Whether Kanishka's deities are all shown from the side, the Buddhas only are shown frontally, indicating that they were copied from contemporary frontal representations of the standing and seated Buddhas in statuary.[20] Both representations of the Buddha and Shakyamuni have both shoulders covered by their monastic gown, indicating that the statues used as models were from the Gandhara school of art, rather than Mathura.

Buddhist statuary under Kanishka

See also: Kushan art

Several Buddhist statues are directly connected to the reign of Kanishka, such as several Bodhisattva statues from the Art of Mathura, while a few other from Gandhara are inscribed with a date in an era which is now thought to be the Yavana era, starting in 186 to 175 BCE.[21]

Dated statuary under Kanishka

Kosambi Bodhisattva, inscribed "Year 2 of Kanishka".[22]

Bala Bodhisattva, Sarnath, inscribed "Year 3 of Kanishka".[23]

"Kimbell seated Buddha", with inscription "year 4 of Kanishka" (131 CE).[24][25] Another similar statue has "Year 32 of Kanishka".[26]

Gandhara Buddhist Triad from Sahr-i-Bahlol, circa 132 CE, similar to the dated Brussels Buddha.[27] Peshawar Museum.[28][29]

Image of a Nāga between two Nāgīs, inscribed in "the year 8 of Emperor Kanishka". 135 CE.[30][31][32]

Buddha from Loriyan Tangai with inscription mentionning the "year 318", thought to be 143 CE.[21]

A Buddha from Loriyan Tangai from the same period.[21]

Kanishka stupa

Main articles: Kanishka stupa and Kanishka casket

Kanishka casket

Remnants of the Kanishka stupa.

Kanishka, surrounded by the Iranian Sun-God and Moon-God (detail)

Relics from Kanishka's stupa in Peshawar, sent by the British to Mandalay, Burma in 1910.

The "Kanishka casket", dated to 127 CE, with the Buddha surrounded by Brahma and Indra, and Kanishka standing at the center of the lower part, British Museum.

The "Kanishka casket" or "Kanishka reliquary", dated to the first year of Kanishka's reign in 127 CE, was discovered in a deposit chamber under Kanishka stupa, during the archaeological excavations in 1908–1909 in Shah-Ji-Ki-Dheri, just outside the present-day Ganj Gate of the old city of Peshawar.[33][34] It is today at the Peshawar Museum, and a copy is in the British Museum. It is said to have contained three bone fragments of the Buddha, which are now housed in Mandalay, Burma.

The casket is dedicated in Kharoshthi. The inscription reads:

"(*mahara)jasa kanishkasa kanishka-pure nagare aya gadha-karae deya-dharme sarva-satvana hita-suhartha bhavatu mahasenasa sagharaki dasa agisala nava-karmi ana*kanishkasa vihare mahasenasa sangharame"

The text is signed by the maker, a Greek artist named Agesilas, who oversaw work at Kanishka's stupas (caitya), confirming the direct involvement of Greeks with Buddhist realisations at such a late date: "The servant Agisalaos, the superintendent of works at the vihara of Kanishka in the monastery of Mahasena" ("dasa agisala nava-karmi ana*kaniskasa vihara mahasenasa sangharame").

The lid of the casket shows the Buddha on a lotus pedestal, and worshipped by Brahma and Indra. The edge of the lid is decorated by a frieze of flying geese. The body of the casket represents a Kushan monarch, probably Kanishka in person, with the Iranian sun and moon gods on his side. On the sides are two images of a seated Buddha, worshiped by royal figures, can be assumed as Kanishka. A garland, supported by cherubs goes around the scene in typical Hellenistic style.

The attribution of the casket to Kanishka has been recently disputed, essentially on stylistic ground (for example the ruler shown on the casket is not bearded, to the contrary of Kanishka). Instead, the casket is often attributed to Kanishka's successor Huvishka.

Kanishka in Buddhist tradition

Kanishka inaugurates Mahayana Buddhism

In Buddhist tradition, Kanishka is often described as an aggressive, hot tempered, rigid, strict, and a bit harsh kind of King before he got converted to Buddhism of which he was very fond, and after his conversion to Buddhism, he became an openhearted, benevolent, and faithful ruler. As in the Sri-dharma-pitaka-nidana sutra:

"At this time the King of Ngan-si (Pahlava) was very aggressive and of a violent nature....There was a bhikshu (monk) arhat who seeing the harsh deeds done by the king wished to make him repent. So by his supernatural force he caused the king to see the torments of hell. The king was terrified and repented and cried terribly and hence dissolved all his negatives within him and got self realised for the first time in life ." Śri-dharma-piṭaka-nidāna sūtra[35]

Additionally, the arrival of Kanishka was reportedly foretold or was predicted by the Buddha, as well as the construction of his stupa:

". . . the Buddha, pointing to a small boy making a mud tope....[said] that on that spot Kaṇiṣka would erect a tope by his name." Vinaya sutra[36]

Coin of Kanishka with the Bodhisattva Maitreya "Metrago Boudo".

The Ahin Posh stupa was dedicated in the 2nd century CE and contained coins of Kaniska

The same story is repeated in a Khotanese scroll found at Dunhuang, which first described how Kanishka would arrive 400 years after the death of the Buddha. The account also describes how Kanishka came to raise his stupa:

"A desire thus arose in [Kanishka to build a vast stupa]....at that time the four world-regents learnt the mind of the king. So for his sake they took the form of young boys....[and] began a stūpa of mud....the boys said to [Kanishka] 'We are making the Kaṇiṣka-stūpa.'....At that time the boys changed their form....[and] said to him, 'Great king, by you according to the Buddha's prophecy is a Saṅghārāma to be built wholly (?) with a large stūpa and hither relics must be invited which the meritorious good beings...will bring."[37]

Chinese pilgrims to India, such as Xuanzang, who travelled there around 630 CE also relays the story:

"Kaṇiṣka became sovereign of all Jambudvīpa (Indian subcontinent) but he did not believe in Karma, but he treated Buddhism with honor and respect as he himself converted to Buddhism intrigued by the teachings and scriptures of it. When he was hunting in the wild country a white hare appeared; the king gave a chase and the hare suddenly disappeared at [the site of the future stupa]....[when the construction of the stūpa was not going as planned] the king lost his patience and took the matter in his own hands and started resurrecting the plans precisely, thus completing the stupas with utmost perfection and perseverance. These two stupas are still in existence and were resorted to for cures by people afflicted with diseases."

King Kanishka because of his deeds was highly respected, regarded, honored by all the people he ruled and governed and was regarded the greatest king who ever lived because of his kindness, humbleness and sense of equality and self-righteousness among all aspects. Thus such great deeds and character of the king Kanishka made his name immortal and thus he was regarded "THE KING OF KINGS"[38]

Transmission of Buddhism to China

Main article: Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

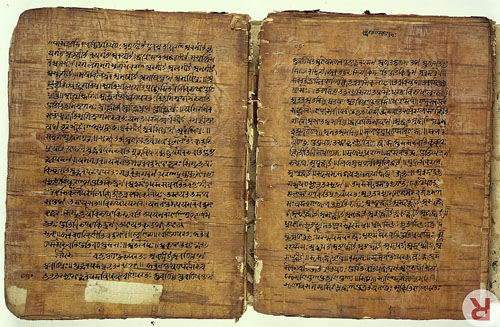

Buddhist monks from the region of Gandhara played a key role in the development and the transmission of Buddhist ideas in the direction of northern Asia from the middle of the 2nd century CE. The Kushan monk, Lokaksema (c. 178 CE), became the first translator of Mahayana Buddhist scriptures into Chinese and established a translation bureau at the Chinese capital Loyang. Central Asian and East Asian Buddhist monks appear to have maintained strong exchanges for the following centuries.

Kanishka was probably succeeded by Huvishka. How and when this came about is still uncertain. It is a fact that there was only one king named Kanishka in the whole Kushan legacy. The inscription on The Sacred Rock of Hunza also shows the signs of Kanishka.

See also

• Menander I

• Greco-Buddhism

Footnotes

1. B.N. Mukhjerjee, Shāh-jī-kī-ḍherī Casket Inscription, The British Museum Quarterly, Vol. 28, No. 1/2 (Summer, 1964), pp. 39-46

2. Bracey, Robert (2017). "The Date of Kanishka since 1960 (Indian Historical Review, 2017, 44(1), 1-41)". Indian Historical Review. 44: 1–41.

3. The Kushans at first retained the Greek language for administrative purposes but soon began to use Bactrian. The Bactrian Rabatak inscription (discovered in 1993 and deciphered in 2000) records that the Kushan king Kanishka the Great (c. 127 AD), discarded Greek (Ionian) as the language of administration and adopted Bactrian ("Arya language"), from Falk (2001): "The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuṣâṇas." Harry Falk. Silk Road Art and Archaeology VII, p. 133.

4. Falk (2001), pp. 121–136. Falk (2004), pp. 167–176.

5. Puri, Baij Nath (1965). India under the Kushāṇas. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

6. Findeisen, Raoul David; Isay, Gad C.; Katz-Goehr, Amira (2009). At Home in Many Worlds: Reading, Writing and Translating from Chinese and Jewish Cultures : Essays in Honour of Irene Eber. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 138. ISBN 9783447061353.

7. Gnoli (2002), pp. 84–90.

8. Sims-Williams and Cribb (1995/6), pp.75–142.

9. Sims-Williams (1998), pp. 79–83.

10. Sims-Williams and Cribb (1995/6), p. 80.

11. Hill (2009), p. 11.

12. "The Rabatak inscription claims that in the year 1 Kanishka I's authority was proclaimed in India, in all the satrapies and in different cities like Koonadeano (Kundina), Ozeno (Ujjain), Kozambo (Kausambi), Zagedo (Saketa), Palabotro (Pataliputra) and Ziri-Tambo (Janjgir-Champa). These cities lay to the east and south of Mathura, up to which locality Wima had already carried his victorious arm. Therefore they must have been captured or subdued by Kanishka I himself." Ancient Indian Inscriptions, S. R. Goyal, p. 93. See also the analysis of Sims-Williams and J. Cribb, who had a central role in the decipherment: "A new Bactrian inscription of Kanishka the Great", in Silk Road Art and Archaeology No. 4, 1995–1996. Also see, Mukherjee, B. N. "The Great Kushanan Testament", Indian Museum Bulletin.

13. Lo Muzio, Ciro (2012). "Remarks on the Paintings from the Buddhist Monastery of Fayaz Tepe (Southern Uzbekistan)". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 22: 189–206.

14. "Samatata coin". British Museum.

15. Wood (2002), illus. p. 39.

16. Sims-Williams (online) Encyclopedia Iranica.

17. H. Humbach, 1975, p.402-408. K. Tanabe, 1997, p.277, M. Carter, 1995, p. 152. J. Cribb, 1997, p. 40. References cited in De l'Indus à l'Oxus.

18. Dobbins (1971).

19. "In Gandhara the appearance of a halo surrounding an entire figure occurs only in the latest phases of artistic production, in the fifth and sixth centuries. By this time in Afghanistan the halo/mandorla had become quite common and is the format that took hold at Central Asian Buddhist sites." in "Metropolitan Museum of Art". http://www.metmuseum.org.

20. The Crossroads of Asia, p. 201. (Full[citation needed] here.)

21. Rhi, Juhyung (2017). Problems of Chronology in Gandharan. Positionning Gandharan Buddhas in Chronology (PDF). Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology. pp. 35–51.

22. Early History of Kausambi p.xxi

23. Epigraphia Indica 8 p.179

24. Seated Buddha with inscription starting with [x] Maharajasya Kanishkasya Sam 4 "Year 4 of the Great King Kanishka" in "Seated Buddha with Two Attendants". http://www.kimbellart.org. Kimbell Art Museum.

25. "The Buddhist Triad, from Haryana or Mathura, Year 4 of Kaniska (ad 82). Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth." in Museum (Singapore), Asian Civilisations; Krishnan, Gauri Parimoo (2007). The Divine Within: Art & Living Culture of India & South Asia. World Scientific Pub. p. 113. ISBN 9789810567057.

26. Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007). The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 48, Fig. 18. ISBN 9781588392244.

27. FUSSMAN, Gérard (1974). "Documents Epigraphiques Kouchans". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 61: 54–57. doi:10.3406/befeo.1974.5193. ISSN 0336-1519. JSTOR 43732476.

28. Rhi, Juhyung. Identifying Several Visual Types of Gandharan Buddha Images. Archives of Asian Art 58 (2008). pp. 53–56.

29. The Classical Art Research Centre, University of Oxford (2018). Problems of Chronology in Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the First International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 23rd-24th March, 2017. Archaeopress. p. 45, notes 28, 29.

30. Sircar, Dineschandra (1971). Studies in the Religious Life of Ancient and Medieval India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-2790-5.

31. Sastri, H. krishna (1923). Epigraphia Indica Vol-17. pp. 11–15.

32. Luders, Heinrich (1961). Mathura Inscriptions. pp. 148–149.

33. Hargreaves (1910–11), pp. 25–32.

34. Spooner, (1908–9), pp. 38–59.

35. Kumar (1973), p. 95.

36. Kumar (1973), p. 91.

37. Kumar (1973). p. 89.

38. Xuanzang, quoted in: Kumar (1973), p. 93.

References

• Bopearachchi, Osmund (2003). De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale (in French). Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes. ISBN 978-2-9516679-2-1.

• Chavannes, Édouard. (1906) "Trois Généraux Chinois de la dynastie des Han Orientaux. Pan Tch'ao (32–102 p. C.); – son fils Pan Yong; – Leang K'in (112 p. C.). Chapitre LXXVII du Heou Han chou." T'oung pao 7, (1906) p. 232 and note 3.

• Dobbins, K. Walton. (1971). The Stūpa and Vihāra of Kanishka I. The Asiatic Society of Bengal Monograph Series, Vol. XVIII. Calcutta.

• Falk, Harry (2001): "The yuga of Sphujiddhvaja and the era of the Kuṣâṇas." In: Silk Road Art and Archaeology VII, pp. 121–136.

• Falk, Harry (2004): "The Kaniṣka era in Gupta records." In: Silk Road Art and Archaeology X (2004), pp. 167–176.

• Foucher, M. A. 1901. "Notes sur la geographie ancienne du Gandhâra (commentaire à un chapitre de Hiuen-Tsang)." BEFEO No. 4, Oct. 1901, pp. 322–369.

• Gnoli, Gherardo (2002). "The "Aryan" Language." JSAI 26 (2002).

• Hargreaves, H. (1910–11): "Excavations at Shāh-jī-kī Dhērī"; Archaeological Survey of India, 1910–11.

• Hill, John E. (2009) Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE. BookSurge, Charleston, South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

• Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (1998). A history of India. London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15481-9.

• Kumar, Baldev. 1973. The Early Kuṣāṇas. New Delhi, Sterling Publishers.

• Sims-Williams, Nicholas and Joe Cribb (1995/6): "A New Bactrian Inscription of Kanishka the Great." Silk Road Art and Archaeology 4 (1996), pp. 75–142.

• Sims-Williams, Nicholas (1998): "Further notes on the Bactrian inscription of Rabatak, with an Appendix on the names of Kujula Kadphises and Vima Taktu in Chinese." Proceedings of the Third European Conference of Iranian Studies Part 1: Old and Middle Iranian Studies. Edited by Nicholas Sims-Williams. Wiesbaden. 1998, pp. 79–93.

• Sims-Williams, Nicholas. Sims-Williams, Nicolas. "Bactrian Language". Encyclopaedia Iranica. 3. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. Accessed: 20/12/2010

• Spooner, D. B. (1908–9): "Excavations at Shāh-jī-kī Dhērī."; Archaeological Survey of India, 1908-9.

• Wood, Frances (2003). The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. University of California Press. Hbk (2003), ISBN 978-0-520-23786-5; pbk. (2004) ISBN 978-0-520-24340-8

External links

• Media related to Kanishka I at Wikimedia Commons

• A rough guide to Kushana history.

• Online Catalogue of Kanishka's Coins

• Coins of Kanishka

• Controversy regarding the beginning of the Kanishka Era.

• Kanishka Buddhist coins

• Photograph of the Kanishka casket

1. From the dated inscription on the Rukhana reliquary

2. Richard Salomon (July–September 1996). "An Inscribed Silver Buddhist Reliquary of the Time of King Kharaosta and Prince Indravarman". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 116 (3): 418–452 [442]. JSTOR 605147.

3. Richard Salomon (1995) [Published online: 9 Aug 2010]. "A Kharosthī Reliquary Inscription of the Time of the Apraca Prince Visnuvarma". South Asian Studies. 11 (1): 27–32. doi:10.1080/02666030.1995.9628492.

4. Jongeward, David; Cribb, Joe (2014). Kushan, Kushano-Sasanian, and Kidarite Coins A Catalogue of Coins From the American Numismatic Society by David Jongeward and Joe Cribb with Peter Donovan. p. 4.