Devanampiya was the Same as Devadatta

As Seleucus’ daughter had come to the Mauryan household, there is general agreement among scholars that Asoka could have been an Indo-Greek; yet his true face remains veiled because he has been dumped at Patna. Wheeler writes:

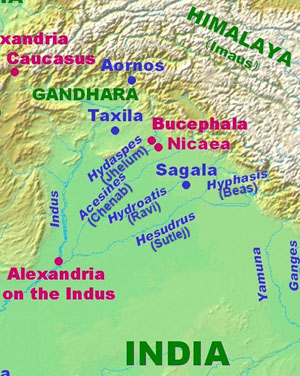

It is just possible that Ashoka had Seleukid blood in his veins; at least his reputed vice-royalty of Taxila in the Punjab during the reign of his father could have introduced him to the living memory of Alexander the Great, and, as king, he himself tells us of proselytizing relations with the Western powers. 49

Wheeler misses that there is not a single archaeological relic that links Asoka with Patna but notes the strong Achaemenian influence on him. Tarn is almost50 awed by the very wide scatter of Diodotus’ coins, but fails to recognise the true bearings of Diodotus. His assertion is at best a hasty oversight:

... coins of Diodotus, for example, have been found in Seistan and in Taxila, places where he never ruled and never even was.51

Narain remarks with greater acuity:

It may be more than coincidence that almost at the same time as Euthydemus established his authority in Bactria Asoka died in India. It is not impossible that he was among those who tried to feed on the carcass of the dead Mauryan empire. 52

Due to Jonesian illusions, Narain cannot even dream that if he had not tried to feed on a carcass, Euthydemus had in fact killed a Maurya—Diodotus II, son of Asoka.53

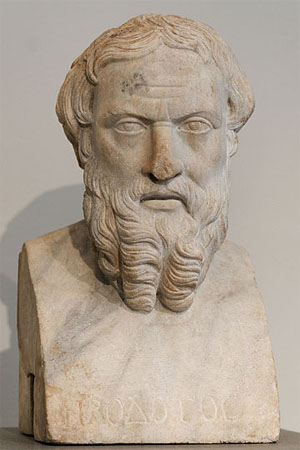

By which name was Asoka known in the West? From the fact that the Greco-Roman writers do not refer to Asoka or his other name Piyadassi, Thapar concludes rather simplistically that he was unknown in the West. This is54 absurd: Asoka was one of the greatest emperors of history, and had sent religious emissaries to the farthest corners of the civilised world. The classical writers must have used a different name—the name Asoka is rare even in his edicts. Only Jones’s blunder obscured that, apart from Piyadassi and Devanampiya, Devadatta was also a name of Asoka. The name dmydty in55 Asoka's famous Taxila pillar Aramaic inscription refers to Devadatta. The line l dmy dty `l’, which Marshall and Andreas translated as ‘for Romedatta’, in fact refers to Damadatta or Devadatta (‘M’ and ‘B’ were often interchanged). Tarn56 notes that Diodorus of the Greeks can be the same as Devadatta of the Indians.57

In fact, Devanampiya, his most common name in the edicts, has the same meaning as Devadatta. Its literal Sanskrit rendering, ‘beloved of the Gods’, is only a secondary sense aimed at his subjects in the sub-continent. Like the Greek word nÒmoj (nomos), the word Nam in Persian means ‘law’, another Persian word for which is Dat. Thus Devanam has the same meaning as Devadat; Piya stands for a redeemer (like Priam of Troy). This clearly shows that Asoka was the same as Diodotus I. After embracing Buddhism, Asoka had to change his name Devadatta as it was the name of Gotama’s hated adversary. In the eighth rock edict he states that his ancestors were also Devanampiyas, which shows that it is a cognomen, not a title—thus even Chandragupta could have been a Devadat or Diodotus (of Erythrae). The term Deva, as known from the Shahnama,(div) the Avesta and Xerxes’ daiva inscription, initially meant a clan, not god. Ignorance of this has led to senseless translations of Asoka's edicts as ‘Gods mingled with men’.

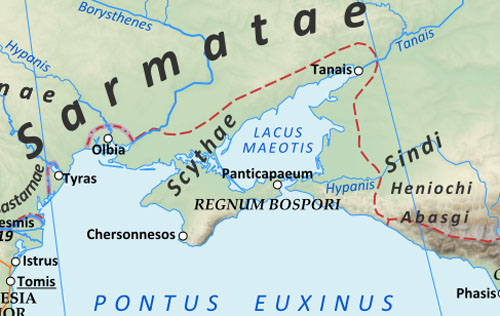

Asoka Ruled Parthia

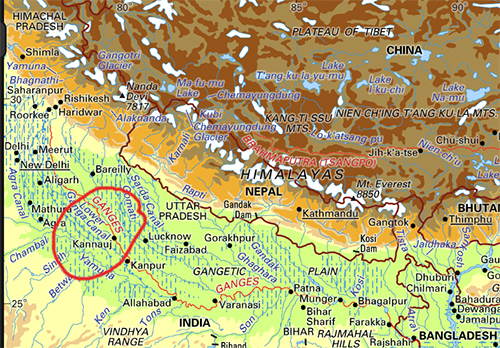

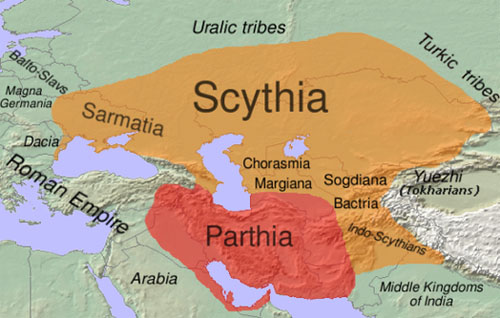

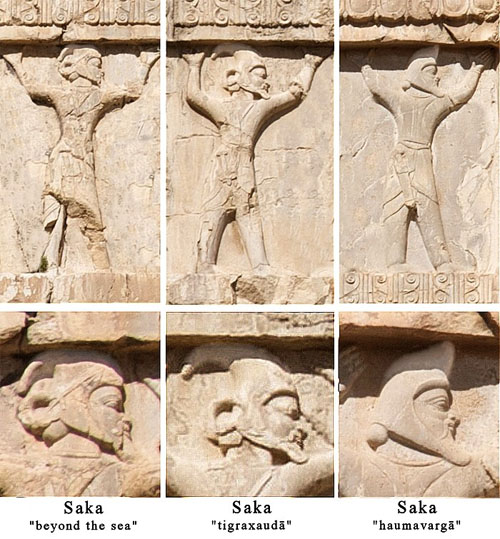

That Diodotus could have ruled Parthia is natural, but it is difficult to place Asoka so far west. Mahalake hi vijitam (‘vast is my empire’), he proclaims majestically in an edict (RE XIV).2: but how vast really was his kingdom? Asoka’s voice reverberates throughout the length and breadth of India, and his edicts usher in a new era in Indian history; but a careful study reveals that his dominion in the West was far more extensive than anyone could imagine. A perplexed Macdonald writes that the first Arsaces

... is sometimes a Parthian, sometimes a Bactrian, sometimes even a descendant of the Achaemenids.58

Significantly, Asoka is also sometimes a Parthian, sometimes a Bactrian, and sometimes even a descendant of the Achaemenids. Many Parthian Kings assumed the title Arsaces, which was also written as Assak. The similarity of Assak with Asoka may appear fortuitous, but it is not so. Another Parthian royal title, Priapati(us) also resembles Piadassi, Asoka’s title. Asoka’s hold on Bactria is beyond dispute, and great scholars like Wheeler note the strong Achaemenian imprint on his architecture. Furthermore, in the Indian texts the Mauryas are said to be descendants of the Nandas. Due to Jones’ blunder, no59 one realised that the Nandas were great Indo-Iranian kings. Darius II whose title was Nonthos, and Artaxerexes III who is cited in the Babylonian records as Nindin, were Nanda kings. Ignoring the bleak archaeological scenario, Thapar60 places Asoka at faraway Patna but, rummaging among the heap of Jonesian absurdum, she wonders why there are no edicts at his so-called capital. She61 also has no difficulty in asserting that the king of Patna could have been a second cousin of the Syrian king Antiochus II. Was Diodotus a descendant of the great Vedic hero Divodasa the Parthava? Indeed, Hillebrandt asserts that Parthia was once within the sphere of greater India. Rostovtzeff’s suggestion62 of Parthian influence on Buddhist art has been greeted with quiet disbelief in academic circles, but this scepticism is groundless. Another great art critic,63 Yazdani, also makes no mistake to identify the characteristic Parthian dress of some women in Ajanta paintings. Busagli writes:64

It should be borne in mind that at the time of its maximum expansion the Parthian kingdom covered an area far greater than that of Iran proper and included the Indian subcontinent [emphasis added], Mesopotamia, Armenia and some of the regions where Indian and Iranian influences overlap.65

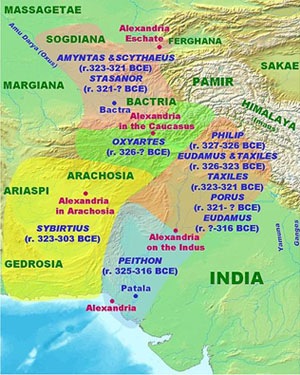

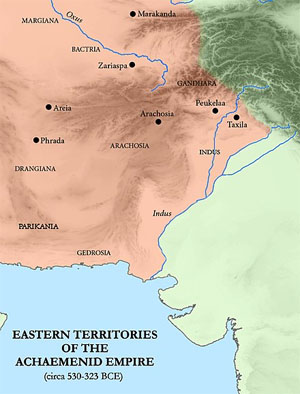

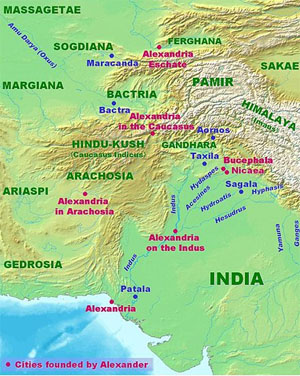

Armed with this definition of Parthia, one can turn to an invaluable clue in Asoka’s edicts on the Mauryas and the Bactrian Greeks. In the Minor Rock Edict I, Asoka explicitly calls himself the ‘king of Pathavi’—an unmistakable allusion to Parthia (Parthava of the Achaemenian records). The word Pathavi66 has been confused by uninformed writers with Prithvi, the Sanskrit word for the Earth, and the statement has been dismissed as just another instance of royal vainglory. This, however, is disproved comprehensively by the fact that his name, Asoka Vardhana, links him with Parthian Kings like Vardanes. Rostovtzeff’s suggestion of Parthian influence becomes only natural if one notes that the king of Pathavi was Asoka. Smith is certain that Seleucus surrendered to Chandragupta the districts of Aria (Herat area), Gedrosia (Baluchistan area), Arachosia (Kandahar region) and Paropamisadae (Kabul region). But, despite his great erudition, Tarn maintained rashly that Asoka67 received no part even of the Paropamisadae. Tarn’s view became untenable in the light of the discovery of Asoka’s Kandahar edict, and even he had to concede that Asoka ‘established some sort of suzerainty over Paropamisadae’.68 Asoka’s own claim of being the king of Pathavi in a way lays the controversy to rest. The Parthian Prince An-shih-kao, who dedicated his life to the spread of Buddhism, is clearly Diodotus. Tsung Ping (AD 375-443) writes in his69 Ming-fo-lun that Buddhism was first brought to China by Asoka. The great70 Indologist F. W. Thomas notes that in his edicts Asoka does not mention his neighbour Diodotus Theos. Thomas tries to explain this within the Jonesian71 framework; but it is strange that the man whose religious overtures won the heart of the entire civilised world failed to impress upon his god-like neighbour. Asoka also does not mention Iran in his edicts; the nearest foreign king that he mentions is Antiochus. This shows that the Syrian King stationed at Selucia72 near Babylon was indeed his neighbour. Asoka does not refer to Diodotus because he was Diodotus himself. According to Wheeler, the first edicts were inscribed ‘in and after 257 BC’. Narain holds that Diodotus proclaimed73 himself as king by about 256 BC. Macdonald points out that Chaldaean74 records indicate that by about 273 BC, Diodotus sent twenty elephants to assist Antiochus I in his war against Ptolemy Philadelphus. The elephants remind75 one of the gift of five hundred elephants by Chandragupta to Seleucus in return for suzerainty over Aria, Arachosia, Paropamisadae and Gedrosia. It is judicious to assume that Diodotus also extracted some favours from Antiochus I in return, and this may correspond to Smith’s view that Asoka became king in 273 BC.76

Asoka seems to have died when Diodotus died. His edicts stopped appearing by about 245 BC. Thapar writes:

The issuing of the pillar edicts was the next known event of Asoka’s reign, and these are dated to the twenty-seventh and twenty-eighth year... It is indeed strange that for the next years until his death in 232 B.C. there were no major edicts. For a man so prolific in issuing edicts this silence of ten years is difficult to explain.77

Significantly, according to most scholars, Diodotus died in 245 BC, and this may be the reason why the edicts stopped appearing. The year of Asoka’s death given by Thapar and others is 232 B.C. but this may be a mistake. Diodotus’78 son, who was also a Diodotus, died in 232 B.C. However, an alternative scenario is also possible: some writers give 232 B.C. as Diodotus’ death, which agrees79 with the Indian texts, but the Indian accounts of Asoka after the death of his wife Asandhimitta (ca. 245 B.C.) are so fanciful that it is more sensible to infer that he had died by ca. 245 B.C. The Indian sources blame Asoka’s Queen Tissarakshita for ordering the death of his son Kunala, which may be an echo80 of the alleged marriage of Diodotus with a Seleucid princess.

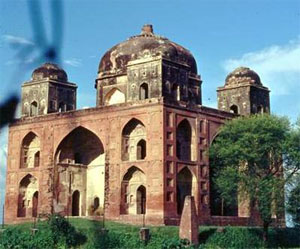

Lion of Chaeronea and Lions on Asokan Pillars

The vanishing of the altars and the true bearings of Sasigupta and Diodotus cast a flood of light on a vexing problem of art history. When the Sarnath pillar with a lion-capital was discovered, it created a flutter all over the world. Marshall,81 an able and unprejudiced writer on Indian art, writes that ‘the Sarnath capital, on the other hand, though by no means a masterpiece, is the product of the most developed art of which the world was cognisant in the third century B.C’.82 However, despite its Indian symbolism, it bespeaks a strange fusion of Hellenic as well as Achaemenian traditions which has baffled all. At first sight there seems to be nothing unnatural for Asoka, alleged by Thapar to be a native of Bihar, to appoint Greek or Persian artisans; but a little circumspection shows83 the absurdity of the proposition. Apart from Jones’s assertion, nothing links84 Asoka to Patna. Wheeler notes the strong Achaemenian influence on Asoka, and recognises the double-lion capitals at Persepolis as the precursors of Asoka’s lions, yet misses the crux of the problem. Ray, another learned critic, writes85 that the Mauryan artists owed much to the Achaemenians, but attributes the stylistic impetus to Hellenistic art. Marshall points out that Asoka’s lion86 capitals represent a totally new era in Indian art; their fixed expression, authentic spirit, canon-based form and stylisation all betray a strong Hellenistic influence. Foucher is also at a loss to explain how the lion symbol sprang up in87 Sarnath. Both Marshall and Smith hold that the finest of the Asokan pillars88,89 were the work of foreign artists. In retrospect, one must pay tribute to scholars like Marshall, Foucher and Ray who were not aware of the true identity of Diodotus I yet made no mistake in recognising the Hellenistic content of Mauryan art.

Surprisingly, no one seems to remember that Alexander had come to Punjab. After the Middle Ages, the first Westerner to notice the Asokan pillars was the Englishman Thomas Coryat who, in AD 1616, was greatly impressed by the superbly polished forty feet-high monolithic column, and presumed that it must have been erected by Alexander the Great ‘in token of his victorie’ over Porus. Moreover, although the lion is an intrusive symbol in India, it was90 common in Macedonia. Not many years before Alexander’s arrival in India, his father Philip had erected a famous lion statue after the historic victory at Chaeronea. Even though we know nothing about the artistic pedigree of the altars, it is sensible to assume that the son had also erected lion capitals in India. It is known that Alexander’s sword had a golden lion head. Were the inscriptions in Greek? This may explain why all of them were summarily reinscribed. The history of the altars throws a flood of light on not only Mauryan and Gandhara art but also the nature of the Hellenistic phenomenon spearheaded by Alexander—a world-citizen. Herzfeld, the famous Orientalist, writes with great insight:

There is no deeper Caesura in the 5000 years of history of the Ancient East than the conquest of Alexander the Great, and there is no archaeological object produced after that period that does not bear its stamp.91

An Altar of Alexander from the Beas Area

It turns out that Coryat was right—truth may be indestructible but at times it is stranger than fiction—as it was Asoka who had re-inscribed the much sought-after pillars of Alexander. In Coryat’s time, the inscriptions on the pillar were unreadable. But today, thanks to Prinsep, we know that it contains an inscription of Asoka. Yet there is more to it than meets the eye—it is known92 that many of Asoka’s pillars were not erected by him. One has to recall that after the Hyphasis mutiny, Alexander gave up his plans to march further east, and to commemorate his Indian expedition he erected twelve massive altars of dressed stone. Arrian writes:

Ο ἱ δ ὲ ἐ βόων τε ο ἷ α ἂ ν ὄ χλος ξυμμιγ ὴ ς χαίρων

βοήσειε κα ὶ ἐ δάκρυον ο ἱ πολλο ὶ α ὐ τ ῶ ν· ο ἱ δ ὲ κα ὶ τ ῇ

σκην ῇ τ ῇ βασιλικ ῇ πελάζοντες η ὔ χοντο

Ἀ λεξάνδρ ῳ πολλ ὰ κα ὶ ἀ γαθά, ὅ τι πρ ὸ ς σφ ῶ ν μόνων

νικηθ ῆ ναι ἠ νέσχετο. ἔ νθα δ ὴ διελ ὼ ν κατ ὰ

τάξεις τ ὴ ν στρατι ὰ ν (5)

δώδεκα βωμο ὺ ς κατασκευάζειν προστάττει, ὕ ψος

μ ὲ ν κατ ὰ το ὺ ς μεγίστους πύργους, ε ὖ ρος δ ὲ

μείζονας ἔ τι ἢ κατ ὰ πύργους, χαριστήρια το ῖ ς

θεο ῖ ς το ῖ ς ἐ ς τοσόνδε ἀ γαγο ῦ σιν α ὐ τ ὸ ν νικ ῶ ντα

κα ὶ μνημε ῖ α τ ῶ ν α ὑ το ῦ (2.) πόνων. ὡ ς δ ὲ

κατεσκευασμένοι α ὐ τ ῷ ο ἱ βωμο ὶ ἦ σαν, θύει δ ὴ ἐ π’

α ὐ τ ῶ ν ὡ ς νόμος κα ὶ ἀ γ ῶ να ποιε ῖ γυμ-νικόν τε κα ὶ

ἱ ππικόν.

He then divided the army into brigades, which he ordered to prepare twelve altars to equal in height the highest military towers, and to exceed them in point of breadth, to serve as thank offerings to the gods who had led him so far as a conqueror, and also as a memorial of his own labours. After erecting the altars he offered sacrifice upon them with the customary rites, and celebrated a gymnastic and equestrian contest. (V.29.1-2)

The Hypanisis also there, a very noble river, which formed the limit of Alexander's march, as the altars erected on its banks prove. See Arrian's Anab. V. 29, where we read that Alexander having arranged his troops in separate divisions ordered them to build on the banks of the Hyphasis twelve altars to be of equal height with the loftiest towers, while exceeding them in breadth. From Curtius we learn that they were formed of square blocks of stone. There has been much controversy regarding their site, but it must have been near the capital of Sopithes, whose name Lassen has identified with the Sanskrit Akapati, 'lord of horses.' These Asvapati were a line of princes whose territory, according to the 12th book of the Ramayana, lay on the right or north bank of the Vipasa (Hyphasis or Bias), in the mountainous part of the Doab comprised between that river and the Upper Iravati. Their capital is called in the poem of Valmiki Rajagriha, which still exists under the name of Rajagiri. At some distance from this there is a chain of heights called Sekandar-giri, or 'Alexander's mountain.'— See St. Martin's E'tude, &c. pp. 108-111.]

-- Ancient India as Described by Megasthenes and Arrian; Being a Translation of the Fragments of the Indika of Megasthenes Collected by Dr. Schwanbeck, and of the First Part of the Indika of Arrian, by J.W. McCrindle

Curiously, unlike most writers who place the altars on the right bank of the river, Pliny places them on the left or the eastern bank:

The Hyphasis was the limit of the marches of Alexander, who, however, crossed [emphasis added] it, and dedicated altars on the further bank. (Plin. HN 6.21)

Pliny’s crucial hint suggests a reappraisal of the riddle of the altars. Precisely how far east had Alexander and his men come? Although Bunbury holds that93 the location of the altars cannot be regarded as known even approximately, the Indian evidence sheds new light. Masson places the altars at the united stream of the Hyphasis and Sutlez. McCrindle also writes that the Sutlez marked the94 limit of Alexander’s march eastward; and this is precisely the locality from95 where Feroze Shah brought the pillar to Delhi.

Thapar ignores Alexander’s voyage and writes heedlessly that, although at present there is no archaeological evidence, Topra must have been an important stopping place on the road from Pataliputra to the north. This not96 only skirts the central issue but also exposes the poverty of Jonesian Indology. There can be little doubt that the Delhi-Topra pillar at Firozabad near Delhi, which bears Asoka’s seventh edict, is a missing altar of Alexander the Great. The very name Chandigarh (Chandragarh) may be an echo of Alakh Chandra, Alexander’s Indian name. In the thirteenth Rock Edict of Asoka, the name Alexander is given as Alika Su(n)dalo.

Alexander and Asoka

Only misjudgment of historians has denied Diodotus his true place in world history. If almost no words seem to be commensurate for the description of Alexander, the same is true of Asoka who swept away all, as it were. His impact on the civilisations of both the East and the West is immense. As Droysen holds, Christianity grew out of an intercourse between Hellenism and the Eastern97 cultures. There can be no doubt that the chief architect of the great expansion of Hellenism and Buddhism, which ultimately paved the way to the rise of Christianity and Islam, was Diodotus. Toynbee writes:

At its maximum extent, Hellenism had expanded in Latin dress as far westward as Britain and Morocco, and in Buddhist dress, as far eastwards as Japan.98

Smith is more specific:

Finally, the central religious literature of both traditions—the Jewish Talmud (an authoritative compendium of law, lore, and interpretation), the New Testament, and the later patristic literature of the Early Church Fathers—are characteristic Hellenistic documents both in form and content. 99

If Alexander was the harbinger of this Hellenistic revolution, Diodotus was its greatest champion. In the thirteenth edict, after declaring that he had himself100 found pleasure rather in conquests by the Dhamma than in conquests by the sword, he says that he had already made such conquests in the realms of the kings of Syria, Egypt, Macedonia, Epirus, and Kyrene, among the Cholas and Pandyas in South India, in Ceylon and among a number of peoples dwelling in the borders of his empire. This was, as Asoka saw it, the Kingdom of God:

… devāṃpiyasā dhaṃmānuṣathi anuvataṃti. Yata pi dutā devāṃpiyasā no yaṃti – te pi sutu devāṃpiyasā dhaṃma-vutaṃ vidhanaṃ dhaṃmānusathi dhaṃmam anuvidhiyaṃti anuvidhiyisaṃti cā. Ye se ladhe etakenā hoti savatā vijaye, piti-lase se.

Everywhere are followed the instructions of the Devānaṃpiya. Even where the envoys of the Devānaṃpiya do not go they (the people of those countries) too, having heard of the Dharma practices, the (Dharma) prescriptions and the Dharma instructions of the Devānaṃpiya follow the Dharma and will continue to follow (it). That conquest which has been won everywhere by this, generates the feeling of satisfaction.101

Diodotus not only utilised Alexander’s monuments, but in many other respects he trod in the latter’s footsteps. In the Rumminidei edict, Asoka reduced taxes102 for the local people as this was the birthplace of Gotama. This has a very distant echo linked with Alexander and Gomata. Impressed by their way of life and civic administration, Alexander extended the boundary of the Ariaspians of Prophthasia and conferred nominal freedom (Arrian III.27). Waiving part of103 the taxes may have been a part of his decree. In the prelude to his famous seventh pillar edict, Asoka states:

Devānaṃpiye Piyadasi lājā hevaṃ āhā: ye atikaṃtaṃ aṃtalaṃ lājāne husu, hevaṃ ichisu - kathaṃ jane dhaṃma-vaḍhiyā vaḍheyā. No cu jane anulupāyā dhaṃma-vaḍhiyā vaḍhithā.

King devānaṃpiya piyadasi spoke thus: The kings who were in times past, desired thus, (viz.) that the people might progress by the promotion of Dharma. But the people did not progress by the adequate progress of Dharma.104

Who are these kings? Despite Asoka’s measured silence on Alexander, it is possible that he is referring to him. Asoka not only used Alexander’s pillars,105 but also undertook to spread the message of homonoia championed by Alexander with a greater resolve.

The Mission of Alexander the Great

In so far as it failed to rout the Prasii, and in view of the great losses in human lives that it caused, Alexander’s Gedrosian operation cannot be called an all-round success. Nevertheless, this unique expedition achieved its goals and marks a high point in world history having no parallel in any other age. That it greatly augmented world trade and ushered in a new era of East-West intercourse cannot be denied. No one could have combined a scientific and a military expedition in the manner Alexander did. It is here that one can recognise the student of Aristotle. His Titanic voyage across so many continents and seas to mingle with the exotic peoples of Africa and Asia appears truly mind-boggling. Nothing could deter him, not the huge Prasiian army or the elephants, not the desert heat, not even the lack of water and food. His emergence from the desert inferno of Gedrosia was a superhuman feat. It is said that he had wept after seeing Nearchus in Carmania (Arrian, Indica xxxv).

When the Macedonians and Greeks first set out with the mandate of the Corinthian League, they were probably guided by simple nationalist motives. But after Alexander was declared a Son of Amon at Siwa, and also under the affectionate guidance of the great Buddhist philosopher Asvaghosa (Calanus)106, this changed into something far more pregnant. More than just a lure for Persian gold or a yearning for the unknown (pÒqoj), Alexander and his followers were driven by a mission to usher in a new world. Russell, one of the towering minds of the last century, squarely reproved Aristotle for his shallow outlook in his Politics:

There is no mention of Alexander, and not even the faintest awareness of the complete transformation that he was effecting in the world.107

Like Cambyses, Alexander got a very bad press. Writers like Badian and Green stress the need for demythologizing, but this demands a precise knowledge of history and geography. It necessary to carefully analyse history to perceive108 Alexander’s greatness, which has been acknowledged through the ages. Like109 many Eastern gods, he was not above sin; his role in his father’s death is far from clear, and his killing of Cleitus and his treatment of Callisthenes were unfortunate yet not inhuman acts. He was certainly less prone to violence than Diodotus in his youth. It is important to consider the possibility that his alienation from his compatriots may have been due to his reinterpretation of Hellenic religion.

For about a century after the voyage, the Orient was witness to momentous events that altered human destiny. It was here that Hellenistic culture and religion were born. It is needless to say that no study of the Hellenistic phenomenon can be complete without reference to Diodotus/Asoka. His edicts indicate that apart from recording his achievements, Alexander’s messages in the altars were also meant for the propagation of homonoia. This is the goal that Asoka took up with a greater zeal. Bevan writes with insight:

One may notice first that nothing was further from Alexander’s own thoughts than that his invasion of India was a mere raid.110

Material evidence for Buddhism in India starts appearing from the fourth century B.C., and this is the era of Alexander. It is impossible to deny Alexander’s role in this renaissance in Indian culture. Only Tarn can see a link between Alexander and Asoka:

For when all is said, we come back at the end to his personality; not the soldier or the statesman, but the man. Whatever Asia did or did not get from him she felt him as she scarcely felt any other; she knew that one of the greatest of the earth had passed. Though his direct influence vanished from India within a generation, and her literature does not know him, he affected Indian history for centuries; for Chandragupta saw him and deduced the possibility of realising in actual fact the conception, handed down from Vedic times, of a comprehensive monarchy in India; hence Alexander indirectly created Asoka’s empire and enabled the spread of Buddhism.111

The influence of Alexander’s pillars, which were later modified by Asoka, on world history is inestimable. Although it cannot be proven conclusively, from considerations of art history, it is not impossible that the Sarnath pillar is also a timeless relic of Alexander the Great modified by Asoka. Due to Jones’s112 error, great scholars like Tarn and Rostovtzeff underrate Alexander’s role. Yet the staggering possibility that the four-lion emblem of India may in fact be a work of Alexander calls for a drastic reassessment of his true legacy. Alexander’s direct influence did not vanish from India. It was due to his vision that East and West first met, and the myriad effects of this fraternisation are beyond any estimate. If homonoia is still a living creed, the credit for part of it must be ascribed to Alexander’s wisdom and tireless energy. His dream of a Brotherhood of Man may forever remain unfulfilled, yet he remains the finest symbol of our vision of a United Nations.

_______________

Notes:

1* In the preparation of this article, the author gratefully remembers the kind encouragement of the late Prof. N. G. L. Hammond.

2 R.E.M. Wheeler, Flames Over Persepolis, Wiedenfeld & Nicholson (London 1968) 129.

3 J. Keay, India Discovered: The Achievement of the British Raj (London 1988) 55.

4 H. Kulke and D. Rothermund, A History of India (London 1990) 86.

5 F. J. Monahan, The Early History of Bengal (Delhi 1974) 225. Monahan (like Vincent Smith, to whom I refer later) was a distinguished British Indologist who was a Civil Servant.

6 Mudrarakshasa, Act vi. Piadamsana is a colloquial error for of Priyadarshana.

7 H.C. Raychaudhuri, Political History of Ancient India (Calcutta 1972) 240.

8 A. C. Sen, Asoka’s Edicts (Calcutta 1956) 168.

9 Archaeologists have found little in India or Iran that can be directly linked to Alexander, and reference to him in Indian literature is scanty though not non-existent. There were about twenty contemporary accounts of Alexander but these are not extant. Aristoboulos and Ptolemy wrote many years later. Historians have been forced to use the later accounts of Arrian, Plutarch and other secondary sources.

10 William Jones, On Asiatick History, Civil and Natural, The Tenth Anniversary Discourse, delivered 28 th February, 1793, by the President at the Asiatick Society of Bengal.

11 Jones’s mistake misled such erudite scholars as Rostovtzeff and Tarn into believing that Alexander is not mentioned in Indian literature and had little impact on Indian civilisation: see D. Musti, The Cambridge Ancient History, vol vii pt.1, ed. F. W. Walbank, A. E. Astin, M. W. Frederiksen and R. M. Ogilvie (Cambridge 1984) 217.; W. W. Tarn, Alexander the Great (Cambridge 1948) 1.142

12 E. Badian, ’Alexander in Iran’, in I. Gershevitch (ed.) The Cambridge History of Iran 2: The Median and Achaemenian Periods (Cambridge 1985) 467. Ptolemy also reported that the omens were unfavourable (Arr., Anab., v. 29). But that may not have been the reason why he turned westwards.

13 ibid.

14 I am indebted to Prof. Hammond for this private communication to me.

15 A. Ghosh, The City in Early Historical India (Simla 1973) 66: ‘... of Pataliputra which is mainly known from non-archaeological sources’. For a more detailed discussion, see R. Pal, Non-Jonesian Indology and Alexander (New Delhi 2002).

16 Kulke and Rothermund [3] 61.

17 V.A. Smith, Ashoka, The Buddhist Emperor of India, (Jaipur 1988) 75.

18 V. Elisseeff, ‘Asiatic Prehistory’, in Encyclopedia of World Art (New York 1960) 3. ‘The Iranian region, with its affinity for the Orient, permitted the development of two different cultural areas: the northwestern one, more properly Iranian, with the localities of Tepe Giyan, Tepe Sialk, Tepe Hissar, and Anau; and the southeastern one, which can be considered Indian, of Baluchistan and the centers of the valley of the Zhob and of Quetta and Amri’. R. N. Frye, on the other hand, stresses only the linguistic diversity of Indo-Iranians, not their common heritage: ‘To the south the Persians and other Iranian invaders found the land occupied by Elamites and related non-Indo-European speakers. Further east were probably Dravidian peoples in Makran, Seistan and Sind, represented today by their descendants, the Brahuis’. R. N. Frye, The Heritage of Persia (London 1962) 27.

19 R.T. Hallock, Persepolis Fortification Tablets, (Chicago 1969). See laso M. B. Garrison and M. C. Root, Seals on the Persepolis Fortification Tablets. I: Images of Heroic Encounter, vol.1 (Chicago 2001). In a private communication to the present writer Prof. Garisson writes, “Too often one feels as if one is working in a vacuum. Good luck on your research”.

20 See the online resource http://www.lumkap.org.uk.

21 A. D. H. Bivar, ‘The Indus Lands’, in The Cambridge Ancient History, ed. I. E. S. Edwards, J. Boardman, N. G. L. Hammond, D. M. Lewis, (Cambridge 1988) 205.

22 E. C. Sachau, Alberuni’s India, vol. 1(London 1910) 40, 380. Apart from his father Suddhodana, Siddhartha’s uncles all had dana-names - Amitodana, Dhotodana, Sukkodana and Sukkhodana. See E. J. Thomas, The Life of Buddha (Delhi 1993) 24.

23 Badian [11] 2.462. Herodotus writes:.. oƒ d ¢pÕ ¹l…ou ¢natolšwn A„q…opej (dixoˆ g¦r d¾ ™strateÚonto) prosetet£cato to‹si 'Indo‹si... oátoi d oƒ ™k tÁj 'As…hj A„q…opej t¦ m n plšw kat£ per 'Indoˆ ™ses£cato... (‘The eastern Ethiopeans—for two nations of this name served in the army—were marshalled with the Indians... Their equipment was in most points like that of the Indians’, Hdt. 7.70.1-7).

24 A. J. Toynbee, A Study Of History 7, Universal States; Universal Churches (Oxford 1979) 650. Toynbee remarks that Herodotus’ India did not include Panjab and Gandhara.

25 W. W. Tarn, Alexander The Great, vol. 2, (Cambridge, 2003) 281. Despite some errors, Tarn’s wide knowledge of both European and Asiatic history gave him a deep insight which remains unmatched.

26 This can be inferred from the Sanskrit drama Mudrarakshasa which recounts the rise of Chandragupta. The fabulous strength of the Nanda army disagrees with the archaeological scenario of fourth century Bihar, and reminds one of the powerful Prasiian army. A century later the Jats and other fierce fighters of Seistan under the Surens humbled the Roman army.

27 R. Lane Fox, Alexander The Great, (London 1974) 372.

28 Asoka's Edicts hint that ritual slaughter of the bird (Mayura) was practised by the Mauryas.

29 A. B. Bosworth, Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great (Cambridge 1988) 150, who gives the name Khanu (maps usually give the name Kohnouj or Kahnuj). Nearby Patali may have been Palibothra. http://www.chnpress.com/news/?section=2&id=6623.

30 V. Smith, Early History of India (Oxford 1961) 181.

31 A. Dow, The History of Hindostan (London 1772). The famous geographer Rennel was the first to identify Patna as Palibothra but later opted for Kanauj. J. Rennel, Memoir of a Map of Hindoostan (London 1778) 49. William Francklin disagreed with Jones and placed Palibothra at Bhagalpur. W. Francklin, Inquiry concerning the site of ancient Palibothra (London 1815) 47. See also S. N. Mukherjee, Sir William Jones: A Study in Eighteenth Century British Attitudes to India 2 (London 1987) 97.

32 J. W. McCrindle (ed. and tr.), The Invasion of India by Alexander the Great as Described by Arrian, Q. Curtius, Diodorus, Plutarch and Justin (New Delhi 1973) 396.

33 Pattala is said to have been a great city and could have been another Mauryan capital.

34 M. Wood, In the Footsteps of Alexander the Great: A Journey from Greece to Asia (Berkeley 1997) 214 discards the Dionysius-Semiramis stories, and proposes that Alexander may have been exploring whether cities could be founded along the coast for trade with India.

35 There may have been a smear campaign launched by the generals who took over after Alexander. The very existence of the junta depended on an extensive falsification and defamation campaign. That Ptolemy had to defend Alexander only shows the extent of such a campaign. Needless to say, Sasigupta could justify his role only by blackening Alexander. The expedition did not immediately bring economic prosperity in Greece, and some Athenians led by the Peripatetics and Demosthenes spared no effort to belittle Alexander.

36 D. B. Lenat, ‘Computer Software for Intelligent Systems’, Scientific American 251 (1984) 157.

37 G. Macdonald, The Hellenic Kingdoms of Syria, Bactria and Parthia in The Cambridge History of India, ed. E. J. Rapson, (New Delhi 1962) 398.

38 Many aspects of Asoka’s life are obscure. Although some punch-marked coins have been associated with his name, this has been disputed. Apart from the edicts, archaeology has unearthed few inscriptions. Palaces unearthed near Patna have been said to be his, but in the absence of inscriptions this is uncertain. Even Taxila, so often associated with his name in the texts, has proved disappointing. Recently inscribed relics of Asoka have been found from Kanganhalli in Karnataka which are said to belong to a later period.

39 While Diodotus-I has numerous coins but no inscriptions, Asoka has many inscriptions but no coins. H.P Ray’s satisfaction about Asoka’s coins is bizzare. H. P. Ray, Ancient India (N. Delhi 2001), 55. Kulke and Rothermund [3] 75, on the other hand, write, “Whereas the Maurya emperors had only produced simple punch-marked coins, even petty Indo-Greek kings issued splendid coins with their image”.

40 E. J. Thomas, The History of Buddhist Thought (London 1933) 154.

41 Coins of Abd Susim, probably a relative of Asoka, have been found at Persepolis. This again hints that Asoka belongs to the northwest.

42 T. W. Rhys Davids, Buddhist India (London 1903) 298.

43 Macdonald [36] 393.

44 P. Gardner, Catalogue of Indian Coins in the British Museum: Greek and Scythic Kings of Bactria and India (London 1886). See also A. von Sallet, ‘Die Nachfolger Alexanders des Grossen in Baktrien und Indien’, Zeitschrift für Numismatik (1879).

45 W. W. Tarn Greeks of Bactria and India (Cambridge 1951) 73.

46 A. K. Narain, The Indo-Greeks (Oxford 1957) 18.

47 Narain ibid, 12.

48 F. L. Holt, Thundering Zeus: The Making of Hellenistic Bacteria (Berkeley 1999), writes much on the Bactrian Greeks but fails to recognise the true Diodotus. Tarn was also an able commentator on the Indian scene, yet he did not recognise Diodotus.

49 R. E. M. Wheeler, Early India and Pakistan to Ashoka (London 1959) 170. See also R. Thapar, Aśoka and the Decline of the Mauryas (Oxford 1961) 20.

50 Ibid, p. 174.

51 Tarn [44] 216.

52 Narain, [45] 20.

53 That cats and dogs fed on the carcass of Artaxerxes III was reported by the Greek sources. It is uncanny that this is also confirmed by the Mudrarakshasa.

54 R. Thapar’s remark that ‘Greek sources mention Sandrocottus and Amitrochates but do not mention Ašoka’ presupposes that the Greeks would also use the name Ašoka current among the Indians. See Thapar [48] 20.

55 B. N. Mukherjee, Studies in the Aramaic Edicts of Asoka (Calcutta 1984) 26.

56 J. H. Marshall A Guide to Taxila (Delhi 1936) 90.

57 Tarn [44] 392.

58 Macdonald [36] 394. Although nearly all scholars reject the Achaemenian link as a fabrication, this is unwarranted. The name Arsaces or Assak could also have been used by Chandragupta who may be Ashkh of the Shahnama; the eldest son of Darius II was Arsaces.

59 Smith [16] 13

60 A. L. Oppenheim, The Babylonian Evidence for Achaemenian Rule in Mesopotamia, in Gershevitch [11] 533.

61 Thapar [48] 233, writes, without any warrant, that the identification of Pataliputra is certain but remains silent on the fact that not a single relic of the Mauryas or the Nandas has been found at Patna. She fails to realise that the wooden palace unearthed at Patna cannot have belonged to Asoka whose architecture lays such stress on stone.

62 A. Hillebrandt, Vedische Mythologie, I (Breslau 1929) 96.

63 M. Busagli, ‘Parthian Art’, in Encyclopedia of World Art.114.

64 M. K. Dhavalikar, in D. C. Sircar (ed.) Foreigners in Ancient India and Lakshmi and Sarasvati in Art and Literature (Calcutta 1970).

65 Busagli [62]106.

66 In this edict, Asoka describes his dominion as Jambudvipa, which is usually assumed to be the same as modern India. In the version of the edict found at Nittur in Tumkur district of Karnataka, the emperor calls it Pathavi. Some scholars have suggested that Jambudvipa was a much wider territory covering nearly the whole of civilised Asia.

67 Smith [16] 75.

68 Tarn [44] 101.

69 R. N. Frye [19] 172 writes that An-hsi is the same as Arshak. As Ghirshman notes, the name is also given as Assak. R. Ghirshman, Iran (Harmondsworth 1954) 243.

70 W. Lai, The Three Jewels in China, in T. Yoshinori (ed.), Buddhist Spirituality (Delhi 1995) 275.

71 F. W. Thomas, ‘Ashoka’, in E. J. Rapson (ed.), Cambridge History of India 1: Ancient India (Cambridge 1922) 453.

72 From Asoka’s references to Antiochus, the relation between the two appears to be cordial. It is not impossible that he also took a favourable view of Asoka’s Dharmavijaya.

73 Wheeler [48], 176.

74 Narain [45] 16.

75 Macdonald [36] 393.

76 Smith [16] 19.

77 Thapar [48] 51.

78 Ibid.

79

80 Thapar [48] 52.

81 It can be argued that Asoka’s lions were borrowed from Nebuchadrezzar’s Babylon—lions guarded the famous E-Sagila—or from the Sumerians who also preferred the lion symbol. As Cumont notes, the lion was a symbol of ancient Lydia; See A. H. Krappe, The Anatolian Lion God, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 65, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1945), pp. 144-154. Four lions also guarded the Meghazil tomb near Amrit, but Gudea’s double lion mace-head is well known. See R. Pal, ‘Gotama Buddha in West Asia’, Annals of the Bhandarkar Research Institute 77 (1996); R. Pal and T. Sato, Gotama Buddha in West Asia (Osaka 1995) 69.

82 J. H. Marshall, ‘The Monuments of Ancient India’, in Rapson [70] 562.

83 Thapar [48].

84 B. M. Barua, Indian Culture, vol.X, p. 34 sees no link between Chandragupta, Asoka’s grandfather, and Bihar. He writes that the language of Asoka’s stone masons was the West Asian Kharosthi. Only two names of Asoka’s governors are known, and by no stretch of imagination can they be linked to Patna: Tushaspa was surely from the northwest. Smith [29]103, writes that the elaborate hair-washing ceremony of the Mauryas is a Persian custom.

85 R. E. M. Wheeler [48] 174: ‘It has long been recognised that these columns, without precedent in Indian architectural forms, represent in partibus the craftmanship of Persia. Actually, the name ‘Persepolitan’ which is commonly given to them by writers on Indian architecture is not altogether happy, since the innumerable columns of Persepolis are invariably fluted, whereas those of Ashoka are unfluted, as indeed was the normal Persian custom. But if for ‘Persepolitan’ we substitute ‘Persian’ or, better still ‘Achaemenid’, there can be no dispute’.

86 N. Ray, Mauryan Art in Age of the Nandas and Mauryas, ed. N. Sastri (Delhi 1967) 346, indirectly hints, with uncommon boldness, at Jones’s error: ‘The fact remains therefore that we have no examples extant of either sculpture or architecture that can definitely be labelled chronologically as pre-Mauryan or perhaps even as pre-Asokan’. He adds later (376) that: ‘Compared with later figural sculptures in the round of Yakshas and their female counterparts or the reliefs of Bharhut, Sanchi and Bodhgaya, the art represented by these crowning lions belongs to an altogether different world of conception and execution, of style and technique, altogether much more complex, urban and civilised. They have nothing archaic or primitive about them, and the presumption is irresistible that the impetus and inspiration of this art must have come from outside’.

87 Marshall [81]

88 A. Foucher, The Beginnings of Buddhist Art

89 V. Smith, A History of Fine Art in India and Ceylon (Oxford 1930) 16. Marshall [81] 564

90 R. E. Pritchard, Odd Tom Coryate: The English Marco Polo. (Stroud 2004). Philostratos’ statement that Apollonius of Tyana, on his journey into India in the second century AD, found the altars still intact and their inscriptions still legible probably indicates that they were in places where Alexander had erected them. See E. H. Bunbury, A History of Ancient Geography Among the Greeks and Romans (London 1883) 503.

91 E. Herzfeld, Iran in The Ancient East (New York 1941) 303.

92 J. Prinsep, Essays on Indian Antiquities: Historic, Numismatic and Palaeographic, (London 1858).

93 E. H. Bunbury, A History of Ancient Geography among the Greeks and Romans from the Earliest Ages till the Fall of the Roman Empire, (London 1883) 444.

94 McCrindle [32] 120

95 ibid.

96 Thapar [48] 230. Authors like Raychaudhuri and Thapar do not treat Alexander’s voyage in detail and hold that Alexander does not belong to Indian history proper.

97 R. Southard, Droysen and the Prussian School of History (Kentucky 1995), 24.

98 A. J. Toynbee, The Greeks and Their Heritage (Oxford 1981) 44.

99 J. Z. Smith, Hellenistic Religions, in P. W. Goetz et al. (edd.), Encyclopedia Britannica (Chicago 1979) 8.751.

100 Wheeler, writes: ‘This book is not a History, but in its last chapter the impersonal disjecta of prehistory may fittingly be assembled in the likeness of a man. Ashoka came to the throne about 268 B.C. and died about 232 B.C. Spiritually and materially his reign marks the first coherent expression of the Indian mind, and, for centuries after the political fabric of his empire had crumbled, his work was implicit in the thought and art of the subcontinent, it is not dead today’. Wheeler [48] 170.

101 Sen [7] 102.

102 This edict has to be examined in view of the widespread frauds in Nepalese archaeology as pointed by T. A. Phelps. See the online resource http://www.lumkap.org.uk. It is more than likely that this pillar was brought from the northwest. A careful study shows that Gomata of the Behistun inscriptions was the true Gotama. See Pal [14]

103 The Ariaspians are the Hariasvas of the Indian texts, who were a lost tribe. The Mahabharata says that King Haryasva never ate flesh in his life (Anusasana Parva 11.67). See V. Mani (ed.), Puranic Encyclopedia (New Delhi 1975) 57. Alexander noted the similarity of their system of justice with that of the Greeks. It is said that the Ariaspians enjoyed special privileges as they had given succour to the starving army of Cyrus, but this cannot be the full story as the holiness of Seistan is well recorded in the Shahnama.

104 Sen [7] 160.

105 The corpus of Asoka’s inscriptions is vast, but one is mystified by what he did not say. He never names his father or his illustrious grandfather. Was he a nephew of Bindusara? See Taranatha’s History of Buddhism in India (Delhi, 1990) 50. Was Asoka’s proscription of samajas (revelling parties) due to his horror of Alexander’s poisoning in such a party?

106 The name given as Sphines by Plutarch is the same as Aspines or Asvaghosa (Plut. Alexander, 65). Asvaghosa may have been an Ariaspian.

107 B. Russell, History of Western Philosophy (London 1969) 196.

108 Badian [11]3.420; See also P. Green, Alexander of Macedon 356-323 B.C.: A Historical Biography (California 1992).

109 I. Worthington, How ‘Great’ was Alexander the Great?, AHB 13.2 (1999) 39-55, attempts, relying almost exclusively on the Greek and Roman sources, to analyse why Alexander was called ‘Great’ even in ancient sources.

110 E. R. Bevan, Alexander The Great, in Rapson [70] 343.

111 Tarn, [10] 1.142

112 Wheeler writes: ‘Equally Persian are the famous lions which crowned the Ashokan column at Sarnath, near Benaras, and have been assumed as the republican badge of India’. Wheeler [48] 174.