Kushan Empire

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 9/16/21

Kushan Empire

30–375

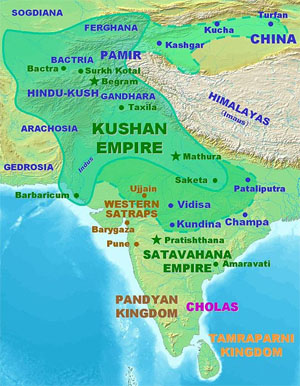

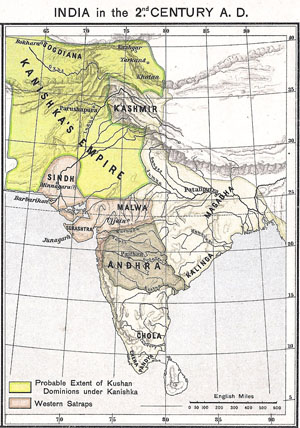

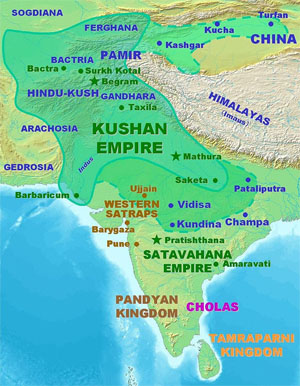

A map of India in the 2nd century AD showing the extent of the Kushan Empire (in yellow) during the reign of Kanishka. Most historians consider the empire to have variously extended as far east as the middle Ganges plain,[1] to Varanasi on the confluence of the Ganges and the Jumna,[2][3] or probably even Pataliputra.[4][5]

Status: Nomadic empire

Capital: Bagram (Kapiśi); Peshawar (Puruṣapura); Taxila (Takṣaśilā); Mathura (Mathurā)

Common languages: Greek (official until ca. 127)[note 1]; Bactrian[note 1] (official from ca. 127); Sanskrit[note 2]

Religion: Buddhism[8]; Hinduism[9]; Zoroastrianism[10]

Government: Monarchy

Emperor

• 30–80: Kujula Kadphises

• 350–375: Kipunada

Historical era/ Classical Antiquity

• Kujula Kadphises unites Yuezhi tribes into a confederation / 30

• Subjugated by the Sasanians, Guptas, and Hepthalites[11] / 375

Area

200 est.[12]: 2,000,000 km2 (770,000 sq mi)

200 est.[13]: 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi)

Currency: Kushan drachma

Preceded by / Succeeded by

Indo-Greek Kingdom / Sasanian Empire

Indo-Parthian Kingdom / Gupta Empire

Indo-Scythians / Nagas of Padmavati

-- / Kidarites

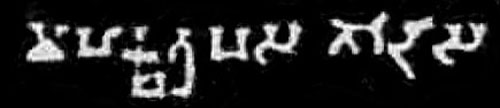

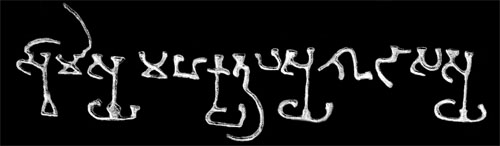

The Kushan Empire (Ancient Greek: Βασιλεία Κοσσανῶν; Bactrian: Κυϸανο, Kushano; Late Brahmi Sanskrit: [x], Ku-ṣā-ṇa, Kuṣāṇa; Devanagari Sanskrit: कुषाण राजवंश, Kuṣāṇa Rājavaṃśa; BHS: Guṣāṇa-vaṃśa; Parthian: [x], Kušan-[x]; Chinese:[x][14]) was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. It spread to encompass much of modern-day territory of Afghanistan, Pakistan and northern India,[15][16][17] at least as far as Saketa and Sarnath near Varanasi (Benares), where inscriptions have been found dating to the era of the Kushan Emperor Kanishka the Great.[note 3]

The Yuezhi (Chinese: 月氏; pinyin: Yuèzhī; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4-chih1, [ɥê ʈʂɻ̩́]) were an ancient people first described in Chinese histories as nomadic pastoralists living in an arid grassland area in the western part of the modern Chinese province of Gansu, during the 1st millennium BC. After a major defeat by the Xiongnu in 176 BC, the Yuezhi split into two groups migrating in different directions: the Greater Yuezhi (Dà Yuèzhī 大月氏) and Lesser Yuezhi (Xiǎo Yuèzhī 小月氏).

The Greater Yuezhi initially migrated northwest into the Ili Valley (on the modern borders of China and Kazakhstan), where they reportedly displaced elements of the Sakas. They were driven from the Ili Valley by the Wusun and migrated southward to Sogdia and later settled in Bactria. The Greater Yuezhi have consequently often been identified with peoples mentioned in classical European sources as having overrun the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, like the Tókharioi (Greek Τοχάριοι; Sanskrit Tukhāra) and Asii (or Asioi). During the 1st century BC, one of the five major Greater Yuezhi tribes in Bactria, the Kushanas (Chinese: 貴霜; pinyin: Guìshuāng), began to subsume the other tribes and neighbouring peoples. The subsequent Kushan Empire, at its peak in the 3rd century AD, stretched from Turfan in the Tarim Basin in the north to Pataliputra on the Gangetic plain of India in the south. The Kushanas played an important role in the development of trade on the Silk Road and the introduction of Buddhism to China.

The Lesser Yuezhi migrated southward to the edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Some are reported to have settled among the Qiang people in Qinghai, and to have been involved in the Liangzhou Rebellion (184–221 AD) against the Chinese Han dynasty. Another group of Yuezhi is said to have founded the city state of Cumuḍa (now known as Kumul and Hami) in the eastern Tarim. A fourth group of Lesser Yuezhi may have become part of the Jie people of Shanxi, who established the Later Zhao state of the 4th century AD (although this remains controversial).

-- Yuezhi, by Wikipedia

The Kushans were most probably one of five branches of the Yuezhi confederation,[21][22] an Indo-European nomadic people of possible Tocharian origin,[23][24][25][26][27] who migrated from northwestern China (Xinjiang and Gansu) and settled in ancient Bactria.[22] The founder of the dynasty, Kujula Kadphises, followed Greek religious ideas and iconography after the Greco-Bactrian tradition, and also followed traditions of Hinduism, being a devotee of the Hindu God Shiva.[28][29] The Kushans in general were also great patrons of Buddhism, and, starting with Emperor Kanishka, they also employed elements of Zoroastrianism in their pantheon.[30] They played an important role in the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and China.

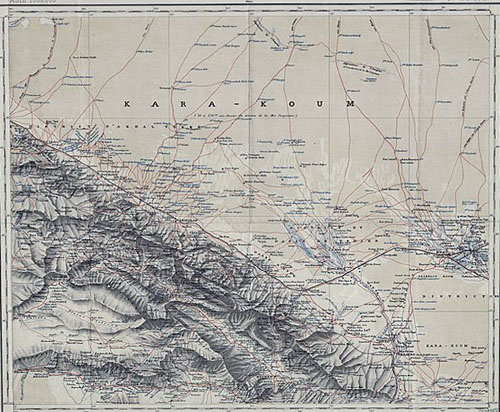

The Kushans possibly used the Greek language initially for administrative purposes, but soon began to use the Bactrian language.[note 1] Kanishka sent his armies north of the Karakoram mountains. A direct road from Gandhara to China remained under Kushan control for more than a century, encouraging travel across the Karakoram and facilitating the spread of Mahayana Buddhism to China. The Kushan dynasty had diplomatic contacts with the Roman Empire, Sasanian Persia, the Aksumite Empire and the Han dynasty of China. The Kushan Empire was at the center of trade relations between the Roman Empire and China: according to Alain Daniélou, "for a time, the Kushana Empire was the centerpoint of the major civilizations".[31] While much philosophy, art, and science was created within its borders, the only textual record of the empire's history today comes from inscriptions and accounts in other languages, particularly Chinese.[32]

The Kushan Empire fragmented into semi-independent kingdoms in the 3rd century AD, which fell to the Sasanians invading from the west, establishing the Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom in the areas of Sogdiana, Bactria and Gandhara. In the 4th century, the Guptas, an Indian dynasty also pressed from the east. The last of the Kushan and Kushano-Sasanian kingdoms were eventually overwhelmed by invaders from the north, known as the Kidarites, and then the Hephthalites.[11]

Origins

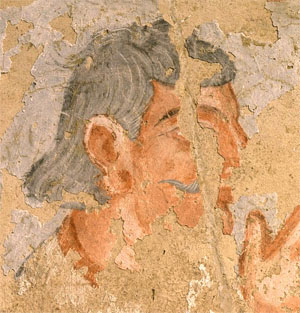

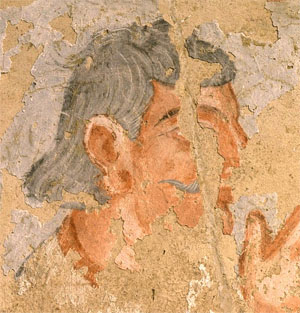

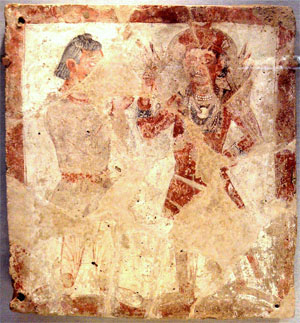

Yuezhi nobleman over a fire altar. Noin-Ula.[33]

Chinese sources describe the Guishuang (貴霜), i.e. the Kushans, as one of the five aristocratic tribes of the Yuezhi.[34] There is scholarly consensus that the Yuezhi were a people of Indo-European origin.[23][35] A specifically Tocharian origin of the Yuezhi is often suggested.[23][24][25][26][27][36] An Iranian, specifically Saka,[37] origin, also has some support among scholars.[38] Others suggest that the Yuezhi might have originally been a nomadic Iranian people, who were then partially assimilated by settled Tocharians, thus containing both Iranian and Tocharian elements.[39]

The Yuezhi were described in the Records of the Great Historian and the Book of Han as living in the grasslands of eastern Xinjiang and northwestern part of Gansu, in the northwest of modern-day China, until their King was beheaded by the Xiongnu (匈奴) who were also at war with China, which eventually forced them to migrate west in 176–160 BC.[40] The five tribes constituting the Yuezhi are known in Chinese history as Xiūmì (休密), Guìshuāng (貴霜), Shuāngmǐ (雙靡), Xìdùn (肸頓), and Dūmì (都密).

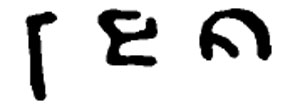

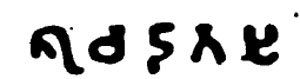

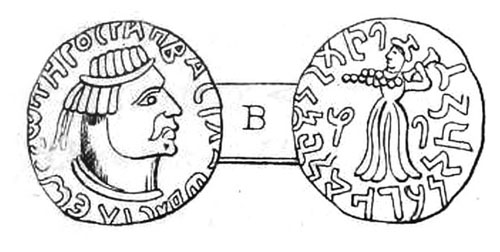

The ethnonym "KOϷϷANOV" (Koshshanoy, "Kushans") in Greek alphabet (with the addition of the letter Ϸ, "Sh") on a coin of the first known Kushan ruler Heraios (1st century AD).

The Yuezhi reached the Hellenic kingdom of Greco-Bactria (in northern Afghanistan and Uzbekistan) around 135 BC. The displaced Greek dynasties resettled to the southeast in areas of the Hindu Kush and the Indus basin (in present-day Afghanistan and Pakistan), occupying the western part of the Indo-Greek Kingdom.

In India, Kushan emperors regularly used the dynastic name ΚΟϷΑΝΟ ("Koshano") on their coinage.[14] Several inscriptions in Sanskrit in the Brahmi script, such as the Mathura inscription of the statue of Vima Kadphises, refer to the Kushan Emperor as [x], Ku-ṣā-ṇa ("Kushana").[14][41] Some later Indian literary sources referred to the Kushans as Turushka, a name which in later Sanskrit sources was confused with Turk, "probably due to the fact that Tukharistan passed into the hands of the western Turks in the seventh century".[42][note 4] Yet, according to Wink, "nowadays no historian considers them to be Turkish-Mongoloid or 'Hun', although there is no doubt about their Central-Asian origin."[42]

Early Kushans

Kushan portraits

Head of a Yuezhi prince (Khalchayan palace, Uzbekistan).[46]

The first king to call himself "Kushan" on his coinage: Heraios (AD 1–30).

Kushan devotee (2nd century AD). Metropolitan Museum of Art (detail)

Portrait of Kushan emperor Vima Kadphises, AD 100-127

Some traces remain of the presence of the Kushans in the area of Bactria and Sogdiana in the 2nd-1st century BC, where they had displaced the Sakas, who moved further south.[47] Archaeological structures are known in Takht-i Sangin, Surkh Kotal (a monumental temple), and in the palace of Khalchayan. On the ruins of ancient Hellenistic cities such as Ai-Khanoum, the Kushans are known to have built fortresses. Various sculptures and friezes from this period are known, representing horse-riding archers,[48] and, significantly, men such as the Kushan prince of Khalchayan with artificially deformed skulls, a practice well attested in nomadic Central Asia.[49][50] Some of the Khalchayan sculptural scenes are also thought to depict the Kushans fighting against the Sakas.[51] In these portrayals, the Yuezhis are shown with a majestic demeanour, whereas the Sakas are typically represented with side-whiskers, and more or less grotesque facial expressions.[51]

The Chinese first referred to these people as the Yuezhi and said they established the Kushan Empire, although the relationship between the Yuezhi and the Kushans is still unclear. Ban Gu's Book of Han tells us the Kushans (Kuei-shuang) divided up Bactria in 128 BC. Fan Ye's Book of Later Han "relates how the chief of the Kushans, Ch'iu-shiu-ch'ueh (the Kujula Kadphises of coins), founded by means of the submission of the other Yueh-chih clans the Kushan Empire."[47]

The earliest documented ruler, and the first one to proclaim himself as a Kushan ruler, was Heraios. He calls himself a "tyrant" in Greek on his coins, and also exhibits skull deformation. He may have been an ally of the Greeks, and he shared the same style of coinage. Heraios may have been the father of the first Kushan emperor Kujula Kadphises.[citation needed]

The Chinese Book of Later Han chronicles then gives an account of the formation of the Kushan empire based on a report made by the Chinese general Ban Yong to the Chinese Emperor c. AD 125:

More than a hundred years later [than the conquest of Bactria by the Yuezhi], the prince [xihou] of Guishuang (Badakhshan) established himself as king, and his dynasty was called that of the Guishuang (Kushan) King. He invaded Anxi (Indo-Parthia), and took the Gaofu (Kabul) region. He also defeated the whole of the kingdoms of Puda (Paktiya) and Jibin (Kapisha and Gandhara). Qiujiuque (Kujula Kadphises) was more than eighty years old when he died. His son, Yangaozhen [probably Vema Tahk (tu) or, possibly, his brother Sadaṣkaṇa ], became king in his place. He defeated Tianzhu [North-western India] and installed Generals to supervise and lead it. The Yuezhi then became extremely rich. All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang [Kushan] king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi.

— Book of Later Han.[52][53]

Diverse cultural influences

In the 1st century BC, the Guishuang (Ch: 貴霜) gained prominence over the other Yuezhi tribes, and welded them into a tight confederation under yabgu (Commander) Kujula Kadphises.[54] The name Guishuang was adopted in the West and modified into Kushan to designate the confederation, although the Chinese continued to call them Yuezhi.

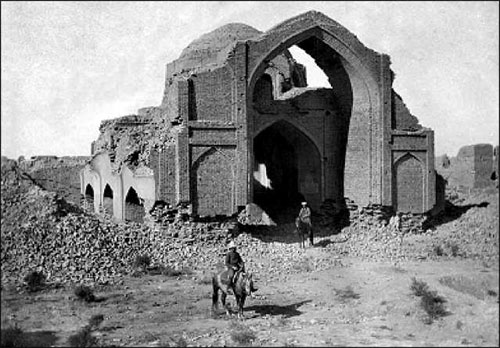

Gradually wresting control of the area from the Scythian tribes, the Kushans expanded south into the region traditionally known as Gandhara (an area primarily in Pakistan's Pothowar and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region) and established twin capitals in Begram.[55] and Charsadda, then known as Kapisa and Pushklavati respectively.[54]

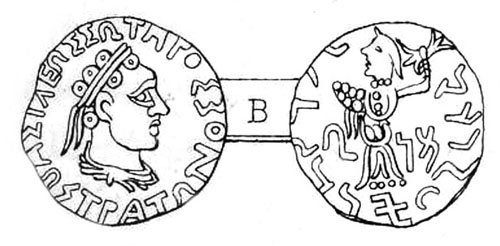

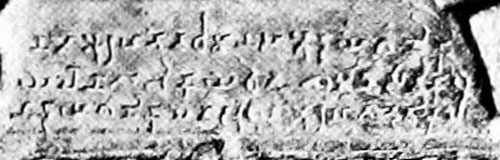

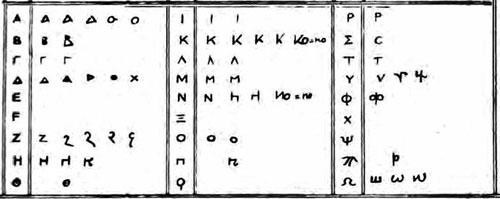

Greek alphabet (narrow columns) with Kushan script (wide columns)

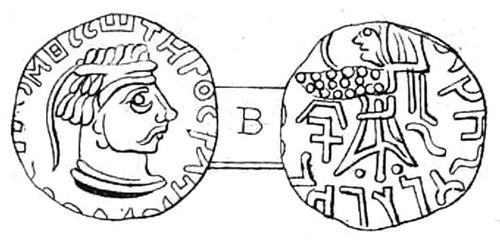

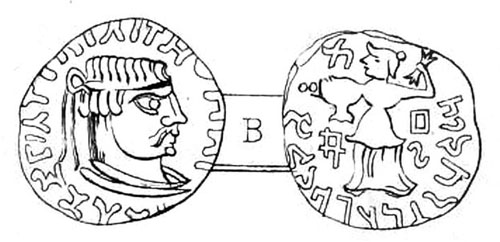

The Kushans adopted elements of the Hellenistic culture of Bactria. They adopted the Greek alphabet to suit their own language (with the additional development of the letter Þ "sh", as in "Kushan") and soon began minting coinage on the Greek model. On their coins they used Greek language legends combined with Pali legends (in the Kharoshthi script), until the first few years of the reign of Kanishka. After the middle of Kanishka's reign, they used Kushan language legends (in an adapted Greek script), combined with legends in Greek (Greek script) and legends in Prakrit (Kharoshthi script).

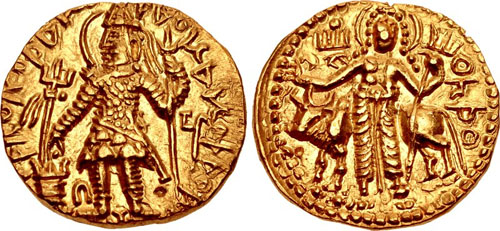

Early gold coin of Kanishka I with Greek language legend and Hellenistic divinity Helios. (c. AD 120).

Obverse: Kanishka standing, clad in heavy Kushan coat and long boots, flames emanating from shoulders, holding a standard in his left hand, and making a sacrifice over an altar. Greek legend:

ΒΑΣΙΛΕΥΣ ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΝ ΚΑΝΗϷΚΟΥ

Basileus Basileon Kanishkoy

"[Coin] of Kanishka, king of kings".

Reverse: Standing Helios in Hellenistic style, forming a benediction gesture with the right hand. Legend in Greek script:

ΗΛΙΟΣ Helios

Kanishka monogram (tamgha) to the left.

The Kushans "adopted many local beliefs and customs, including Zoroastrianism and the two rising religions in the region, the Greek cults and Buddhism".[55] From the time of Vima Takto, many Kushans started adopting aspects of Buddhist culture, and like the Egyptians, they absorbed the strong remnants of the Greek culture of the Hellenistic Kingdoms, becoming at least partly Hellenised. The great Kushan emperor Vima Kadphises may have embraced Shaivism (a sect of Hinduism), as surmised by coins minted during the period.[9] The following Kushan emperors represented a wide variety of faiths including Buddhism, Zoroastrianism and Shaivism.

The rule of the Kushans linked the seagoing trade of the Indian Ocean with the commerce of the Silk Road through the long-civilized Indus Valley. At the height of the dynasty, the Kushans loosely ruled a territory that extended to the Aral Sea through present-day Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan into northern India.[54]

The loose unity and comparative peace of such a vast expanse encouraged long-distance trade, brought Chinese silks to Rome, and created strings of flourishing urban centers.[54]

Territorial expansion

Kushan territories (full line) and maximum extent of Kushan control under Kanishka the Great.[56] The extent of Kushan control is notably documented in the Rabatak inscription.[5][57][note 5][58] The northern expansion into the Tarim Basin is mainly suggested by coin finds and Chinese chronicles.[59][60]

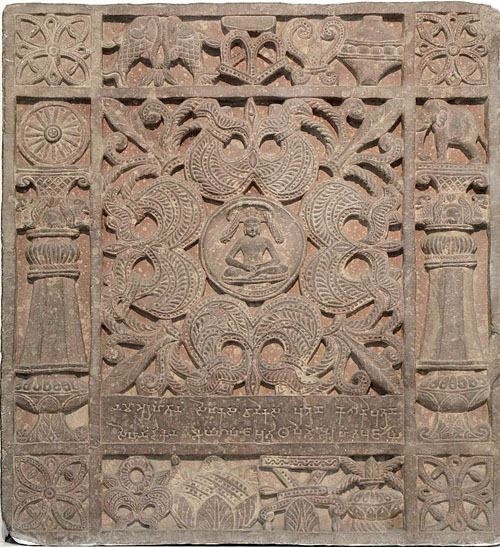

Rosenfield notes that archaeological evidence of a Kushan rule of long duration is present in an area stretching from Surkh Kotal, Begram, the summer capital of the Kushans, Peshawar, the capital under Kanishka I, Taxila, and Mathura, the winter capital of the Kushans.[61] The Kushans introduced for the first time a form of governance which consisted of Kshatrapas (Brahmi:[x], Kṣatrapa, "Satraps") and Mahakshatrapa (Brahmi:[x], Mahakṣatrapa, "Great Satraps").[62]

Other areas of probable rule include Khwarezm and its capital city of Toprak-Kala,[61][63] Kausambi (excavations of Allahabad University),[61] Sanchi and Sarnath (inscriptions with names and dates of Kushan kings),[61] Malwa and Maharashtra,[64] and Odisha (imitation of Kushan coins, and large Kushan hoards).[61]

Map showing the four empires of Eurasia in the 2nd century AD. "For a time, the Kushan Empire was the centerpoint of the major civilizations".[31]

Kushan invasions in the 1st century AD had been given as an explanation for the migration of Indians from the Indian Subcontinent toward Southeast Asia according to proponents of a Greater India theory by 20th-century Indian nationalists. However, there is no evidence to support this hypothesis.[65]

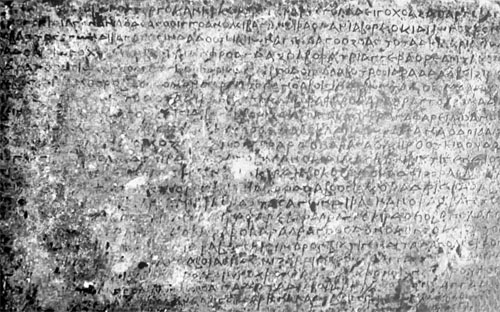

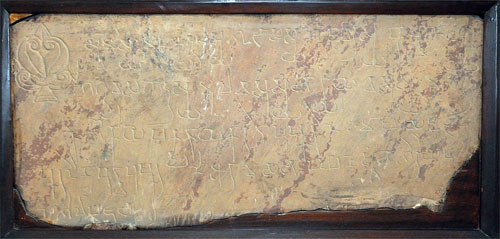

The recently discovered Rabatak inscription confirms the account of the Hou Hanshu, Weilüe, and inscriptions dated early in the Kanishka era (incept probably AD 127), that large Kushan dominions expanded into the heartland of northern India in the early 2nd century AD.[clarify] Lines 4 to 7 of the inscription describe the cities which were under the rule of Kanishka,[note 6] among which six names are identifiable: Ujjain, Kundina, Saketa, Kausambi, Pataliputra [PALIBOTRA!], and Champa (although the text is not clear whether Champa was a possession of Kanishka or just beyond it).[66][note 5][67][68] The Buddhist text Śrīdharmapiṭakanidānasūtra—known via a Chinese translation made in AD 472—refers to the conquest of Pataliputra by Kanishka.[69] A 2nd century stone inscription by a Great Satrap named Rupiamma was discovered in Pauni, south of the Narmada river, suggesting that Kushan control extended this far south, although this could alternatively have been controlled by the Western Satraps.[70]

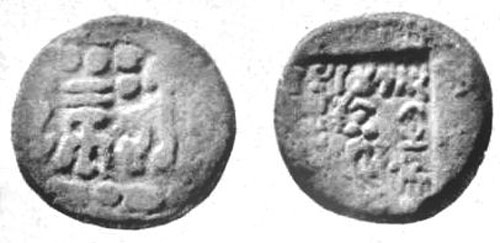

Eastern reach as far as Bengal: Samatata coinage of king Vira Jadamarah, in imitation of the Kushan coinage of Kanishka I. The text of the legend is a meaningless imitation. Bengal, circa 2nd-3rd century AD.[???!!!][71]

In the East, as late as the 3rd century AD, decorated coins of Huvishka were dedicated at Bodh Gaya together with other gold offerings under the "Enlightenment Throne" of the Buddha, suggesting direct Kushan influence in the area during that period.[72] Coins of the Kushans are found in abundance as far as Bengal, and the ancient Bengali state of Samatata issued coins copied from the coinage of Kanishka I, although probably only as a result of commercial influence.[73][71][74] Coins in imitation of Kushan coinage have also been found abundantly in the eastern state of Orissa.[75]

In the West, the Kushan state covered the Pārata state of Balochistan, western Pakistan, Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan was known for the Kushan Buddhist city of Merv.[61]

Northward, in the 1st century AD, the Kujula Kadphises sent an army to the Tarim Basin to support the city-state of Kucha, which had been resisting the Chinese invasion of the region, but they retreated after minor encounters.[76] In the 2nd century AD, the Kushans under Kanishka made various forays into the Tarim Basin, where they had various contacts with the Chinese. Kanishka held areas of the Tarim Basin apparently corresponding to the ancient regions held by the Yüeh-zhi, the possible ancestors of the Kushan. There was Kushan influence on coinage in Kashgar, Yarkand, and Khotan.[59] According to Chinese chronicles, the Kushans (referred to as Da Yuezhi in Chinese sources) requested, but were denied, a Han princess, even though they had sent presents to the Chinese court. In retaliation, they marched on Ban Chao in AD 90 with a force of 70,000 but were defeated by the smaller Chinese force. Chinese chronicles relate battles between the Kushans and the Chinese general Ban Chao.[68] The Yuezhi retreated and paid tribute to the Chinese Empire. The regions of the Tarim Basin were all ultimately conquered by Ban Chao. Later, during the Yuánchū period (AD 114–120), the Kushans sent a military force to install Chenpan, who had been a hostage among them, as king of Kashgar.[77]

Main Kushan rulers

Kushan rulers are recorded for a period of about three centuries, from circa AD 30 to circa 375, until the invasions of the Kidarites. They ruled around the same time as the Western Satraps, the Satavahanas, and the first Gupta Empire rulers.[citation needed]

Kujula Kadphises (c. 30 – c. 80)

Main article: Kujula Kadphises

Kushan Empire

30 CE–350 CE

Heraios / 1-30 CE

Kujula Kadphises / 50–90 CE

Vima Takto / 90-113 CE

Vima Kadphises / 113-127 CE

Kanishka I / 127-151 CE

Huvishka / 151-190 CE

Vasudeva I / 190-230 CE

Kanishka II / 230-247 CE

Vāsishka / 247-267 CE

Kanishka III / 267-270 CE

Vasudeva II / 270-300 CE

Mahi / 300-305 CE

Shaka / 305-335 CE

Kipunada / 335-350 CE

...the prince [elavoor] of Guishuang, named thilac [Kujula Kadphises], attacked and exterminated the four other xihou. He established himself as king, and his dynasty was called that of the Guishuang [Kushan] King. He invaded Anxi [Indo-Parthia] and took the Gaofu [Kabul] region. He also defeated the whole of the kingdoms of Puda [Paktiya] and Jibin [Kapisha and Gandhara]. Qiujiuque [Kujula Kadphises] was more than eighty years old when he died."

— Hou Hanshu[52]

These conquests by Kujula Kadphises probably took place sometime between AD 45 and 60 and laid the basis for the Kushan Empire which was rapidly expanded by his descendants.[citation needed]

Kujula issued an extensive series of coins and fathered at least two sons, Sadaṣkaṇa (who is known from only two inscriptions, especially the Rabatak inscription, and apparently never ruled), and seemingly Vima Takto.[citation needed]

Kujula Kadphises was the great-grandfather of Kanishka.[citation needed]

Vima Taktu or Sadashkana (c. 80 – c. 95)

Main article: Vima Takto

Vima Takto (Ancient Chinese: 閻膏珍 Yangaozhen) is mentioned in the Rabatak inscription (another son, Sadashkana, is mentioned in an inscription of Senavarman, the King of Odi). He was the predecessor of Vima Kadphises, and Kanishka I. He expanded the Kushan Empire into the northwest of South Asia. The Hou Hanshu says:

"His son, Yangaozhen [probably Vema Tahk (tu) or, possibly, his brother Sadaṣkaṇa], became king in his place. He defeated Tianzhu [North-western India] and installed Generals to supervise and lead it. The Yuezhi then became extremely rich. All the kingdoms call [their king] the Guishuang [Kushan] king, but the Han call them by their original name, Da Yuezhi."

— Hou Hanshu[52]

Vima Kadphises (c. 95 – c. 127)

Main article: Vima Kadphises

Vima Kadphises (Kushan language: Οοημο Καδφισης) was a Kushan emperor from around AD 95–127, the son of Sadashkana and the grandson of Kujula Kadphises, and the father of Kanishka I, as detailed by the Rabatak inscription.[citation needed]

Vima Kadphises added to the Kushan territory by his conquests in Bactria. He issued an extensive series of coins and inscriptions. He issued gold coins in addition to the existing copper and silver coinage.[citation needed]

Kanishka I (c. 127 – c. 150)

Main article: Kanishka

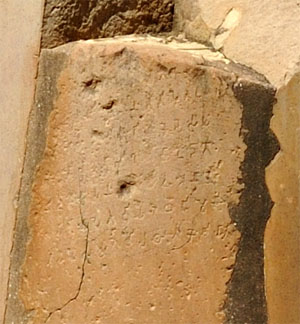

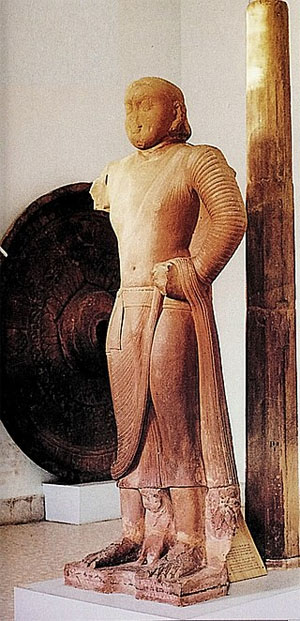

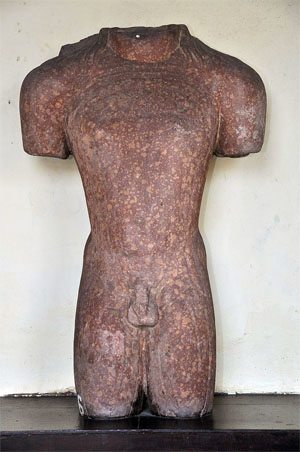

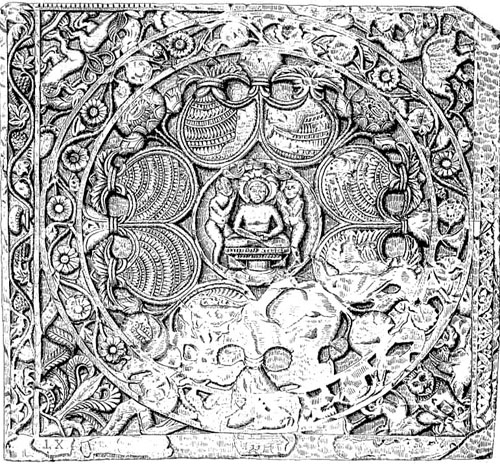

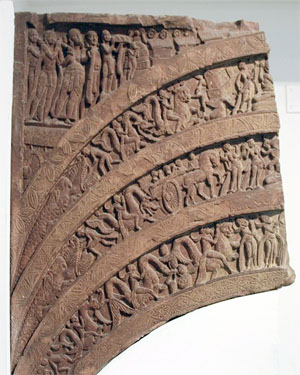

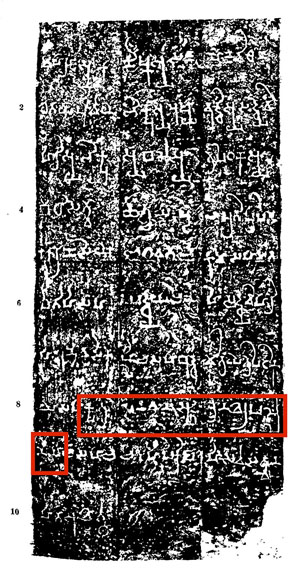

Mathura statue of Kanishka

Statue of Kanishka in long coat and boots, holding a mace and a sword, in the Mathura Museum. An inscription runs along the bottom of the coat.

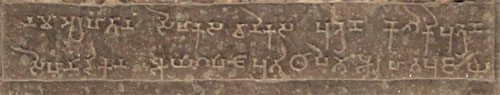

The inscription is in middle Brahmi script:

Mahārāja Rājadhirāja Devaputra Kāṇiṣka

"The Great King, King of Kings, Son of God, Kanishka".[78]

Mathura art, Mathura Museum

The rule of Kanishka the Great, fourth Kushan king, lasted for about 23 years from c. AD 127.[79] Upon his accession, Kanishka ruled a huge territory (virtually all of northern India), south to Ujjain and Kundina and east beyond Pataliputra, according to the Rabatak inscription:

In the year one, it has been proclaimed unto India, unto the whole realm of the governing class, including Koonadeano (Kaundiny, Kundina) and the city of Ozeno (Ozene, Ujjain) and the city of Zageda (Saketa) and the city of Kozambo (Kausambi) and the city of Palabotro (Pataliputra) and as far as the city of Ziri-tambo (Sri-Champa), whatever rulers and other important persons (they might have) he had submitted to (his) will, and he had submitted all India to (his) will.

— Rabatak inscription, Lines 4–8

His territory was administered from two capitals: Purushapura (now Peshawar in northwestern Pakistan) and Mathura, in northern India. He is also credited (along with Raja Dab) for building the massive, ancient Fort at Bathinda (Qila Mubarak), in the modern city of Bathinda, Indian Punjab. [Patiala!] [citation needed]

The Kushans also had a summer capital in Bagram (then known as Kapisa), where the "Begram Treasure", comprising works of art from Greece to China, has been found.

Female standing on a mythological creature, 1st-2nd century AD. Discovered at Begram during the 1930s. Ivory; Height: 18 inches. Collection: National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul. Excavated in the 1930s, the city of Begram contained two large rooms filled with an amazing array of goods, including Roman glass and metalwork, Chinese lacquer, and ivory plaques and sculptures that show strong parallels to Indian art. This sculpture is one of three that were next to one another when unearthed. All three show a young, voluptuous woman standing on the back of a makara, a creature derived from Indian mythology that has the tail of a fish and the body and face of a crocodile. Symbolic of the powers of water, makara are often associated with a river goddess in India. However, this sculpture and the other two similar works were probably used as the legs of a table, making it unlikely that they were intended as representations of river goddesses. Photo: © Thierry Ollivier / Musee Guimet. Text © Fred Hiebert / National Geographic Society.

Statuette of the god Harpocrates, 1st-2nd century AD. Discovered at Begram. Bronze; Height 9-1/2 inches. Collection: National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul. This superb bronze statuette belongs to a group of bronze objects bearing classical subjects that was imported from the Roman Mediterranean, probably Egypt and Italy. The child shown here with his finger to his mouth represents Harpocrates, the Hellenized form of the Egyptian god Horus, son of Isis and Osiris. The soft modeling and the curve of the body derive from the style of the fourth-century-BC Greek sculptor Praxiteles. Together with glassware from Alexandria, the bronzes are evidence of an active long-distance maritime trade. Sea routes connected the Mediterranean to the Far East through the Indian Ocean when Afghanistan, under the Kushan dynasty, was one of the major powers of the ancient world. Photo: © Thierry Ollivier / Musee Guimet. Text © Fred Hiebert / National Geographic Society.

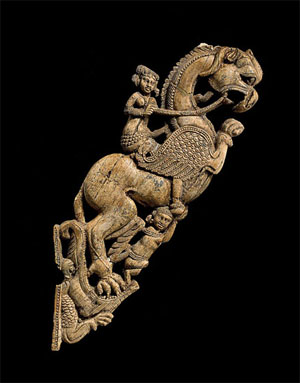

Bracket with a female riding a fantastic creature, 1st-2nd century AD. Discovered at Begram during the 1930s. Ivory; 11-7/8 inches high. Collection: National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul. Rearing dramatically, the composite creature that forms this bracket has the body of a lion, the wings of an eagle, and the beak of a bird of prey. Known as sardula in Indian art, this beast may be derived from the griffin of Greek and Roman art. While either tradition could have contributed this powerful animal to the repertory of the Begram ivories, the treatment of the female rider clearly points to India. Artistic traditions from India are also seen in the small figure supporting the front paws of the beast, one of the earth spirits known as yakshas, while the crocodile-like figure with the yawning mouth is the makara, which is symbolic of the powers of water. Photo: © Thierry Ollivier / Musee Guimet. Text © Fred Hiebert / National Geographic Society.

Flask in the shape of a fish, 1st-2nd century AD. Discovered at Begram during the 1930s. Blown glass; 3-3/8 x 4-1/4 x 7-7/8 inches. Collection: National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul. No less important than the extraordinary collection of Indian ivories -- and found in the same "treasure chamber" -- is a group of classical objects that include glassware, stucco medallions, and bronze statuettes. The collection of glassware is of outstanding quality scarcely equaled by that of any museum in the Western world. The glass objects display different techniques, shapes, and decoration, but all seem to originate in workshops of Roman Alexandria. This bottle in the shape of a fish is an exquisite example of a type of perfume container that was very popular in the Greco-Roman world. Photo: © Thierry Ollivier / Musee Guimet. Text © Fred Hiebert / National Geographic Society.

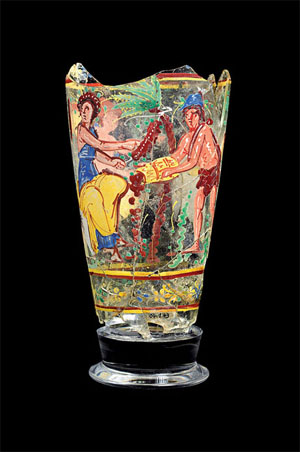

Goblet depicting a scene of date harvesting, 1st-2nd century AD. Discovered at Begram during the 1930s. Colorless glass, antimony and iron oxides; Height: 9-3/4 x Diameter: 4-5/8 inches. Collection: National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul. The enameled goblets from Begram are a unique document of ancient glassmaking, previously known from only a handful of fragments of glassware found in various sites scattered within the Roman Empire, from the late first to the third century A.D. The favorite subjects were combat between gladiators or heroes and genre scenes, such as hunting and fishing, set in exotic landscapes evocative of Egypt. This goblet shows four figures, surrounded by a grove of palm trees, who seem to be engaged in harvesting dates. The strong sense of color and the sketchy freedom of this and other miniature paintings give them an extraordinary vivacity that places them in the ranks of pictorial masterpieces of the ancient world. Photo: © Thierry Ollivier / Musee Guimet. Text © Fred Hiebert / National Geographic Society.

Medallion with a bust of a youth, 1st-2nd century AD. Discovered at Begram. Plaster; Diameter 8-3/4 inches. Collection: National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul. The bust depicts a youth of idealized beauty -- perhaps a poet or a young hero. It belongs to a distinctive group found at Begram of fifty plaster casts depicting mythological subjects and other images typical of the classical world. Plaster casts similar to this one have been found in various sites from Egypt to Ukraine, but the Begram group is unmatched in the highly refined delicacy of the modeling. These casts were most probably taken from the central medallions (emblemata) of Greek silver plates of the third century BC. They may have been taken at Begram, although it is also possible that they reached the city through the Silk Road trade route as models for use by local metalworkers or samples for their clients. Photo: © Thierry Ollivier / Musee Guimet. Text © Fred Hiebert / National Geographic Society.

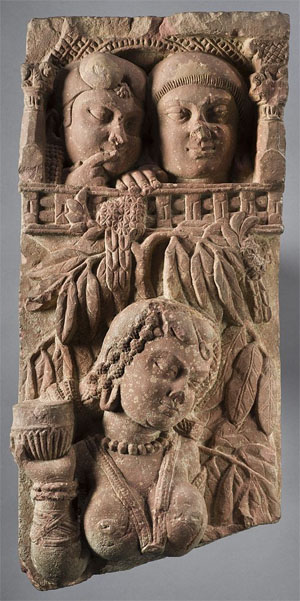

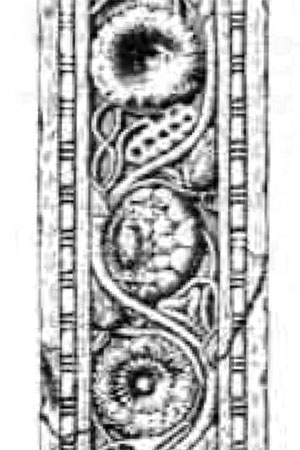

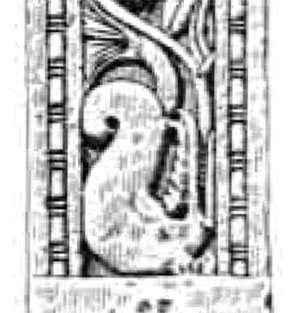

Plaque with women under gateways, 1st-2nd century AD. Discovered at Begram during the 1930s. Ivory; 5-3/8 x 9-3/4 inches. Collection: National Museum of Afghanistan, Kabul. The fact that women and their activities predominate in the imagery of the Begram ivories has led some scholars to suggest that the ivories were intended for use in women's quarters. This densely carved plaque shows four women, one of whom is holding a child. The voluptuous bodies, diaphanous clothing, and lush jewelry parallel traditional Indian representations, which also focus on the beauty and fertility of young women. The figures are shown standing underneath gateways that derive from Indian architectural traditions and are lushly decorated with floral and geometric motifs. Photo: © Thierry Ollivier / Musee Guimet. Text © Fred Hiebert / National Geographic Society.

-- 023. Begram, by Cultural Property Training Resource Afghanistan

According to the Rabatak inscription, Kanishka was the son of Vima Kadphises, the grandson of Sadashkana, and the great-grandson of Kujula Kadphises. Kanishka's era is now generally accepted to have begun in 127 on the basis of Harry Falk's ground-breaking research.[18][19] Kanishka's era was used as a calendar reference by the Kushans for about a century, until the decline of the Kushan realm.[citation needed]

Huvishka (c. 150 – c. 180)

Main article: Huvishka

Huvishka (Kushan: Οοηϸκι, "Ooishki") was a Kushan emperor from the death of Kanishka (assumed on the best evidence available to be in 150) until the succession of Vasudeva I about thirty years later. His rule was a period of retrenchment and consolidation for the Empire. In particular he devoted time and effort early in his reign to the exertion of greater control over the city of Mathura.[citation needed]

Mathura is a city and the administrative headquarters of Mathura district in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It is located approximately 57.6 kilometres (35.8 mi) north of Agra, and 166 kilometres (103 mi) south-east of Delhi; about 14.5 kilometres (9.0 mi) from the town of Vrindavan, and 22 kilometres (14 mi) from Govardhan. In ancient times, Mathura was an economic hub, located at the junction of important caravan routes.

-- Mathura, by Wikipedia

Vasudeva I (c. 190 – c. 230)

Main article: Vasudeva I

Vasudeva I (Kushan: Βαζοδηο "Bazodeo", Chinese: 波調 "Bodiao") was the last of the "Great Kushans". Named inscriptions dating from year 64 to 98 of Kanishka's era suggest his reign extended from at least AD 191 to 225. He was the last great Kushan emperor, and the end of his rule coincides with the invasion of the Sasanians as far as northwestern India, and the establishment of the Indo-Sasanians or Kushanshahs in what is nowadays Afghanistan, Pakistan and northwestern India from around AD 240.[citation needed]

The Sasanian or Sassanid Empire, officially known as the Empire of Iranians, and also called the Neo-Persian Empire by historians, was the last Persian imperial dynasty before the Muslim conquest in the mid seventh century AD. Named after the House of Sasan, it endured for over four centuries, from 224 to 651 AD, making it the longest-lived Persian dynasty. The Sasanian Empire succeeded the Parthian Empire, and reestablished the Iranians as a superpower in late antiquity, alongside its neighbouring arch-rival, the Roman-Byzantine Empire.

The Sasanian Empire was founded by Ardashir I, a local Iranian ruler who rose to power as Parthia weakened from internal strife and wars with Rome. After defeating the last Parthian shahanshah, Artabanus IV, in the battle of Hormozdgan in 224, he established the Sasanian dynasty and set out to restore the legacy of the Achaemenid Empire by expanding Iran's dominions. At its greatest extent, the Sasanian Empire encompassed all of present-day Iran and Iraq and stretched from the eastern Mediterranean (including Anatolia and Egypt) to Pakistan, and from parts of southern Arabia to the Caucasus and Central Asia. According to legend, the vexilloid of the Empire was the Derafsh Kaviani.

The period of Sasanian rule is considered a high point in Iranian history, and in many ways was the peak of ancient Iranian culture before the Muslim conquest and subsequent Islamisation. The Sasanians tolerated the varied faiths and cultures of their subjects, developed a complex, centralised government bureaucracy and revitalized Zoroastrianism as a legitimising and unifying force of their rule. They also built grand monuments and public works and patronised cultural and educational institutions. The empire's cultural influence extended far beyond its territorial borders—including Western Europe, Africa, China and India—and helped shape European and Asian medieval art. Persian culture became the basis for much of Islamic culture, influencing art, architecture, music, literature, and philosophy throughout the Muslim world.

-- Sasanian Empire, by Wikipedia

Vāsishka (c. 247 – c. 267)

Main article: Vāsishka

Coin of Kushan ruler Huvishka diademed, with deity Pharro. Circa AD 152-192

Vāsishka was a Kushan emperor who seems to have had a 20-year reign following Kanishka II. His rule is recorded at Mathura, in Gandhara and as far south as Sanchi (near Vidisa), where several inscriptions in his name have been found, dated to the year 22 (the Sanchi inscription of "Vaksushana" – i.e., Vasishka Kushana) and year 28 (the Sanchi inscription of Vasaska – i.e., Vasishka) of a possible second Kanishka era.[80][81]

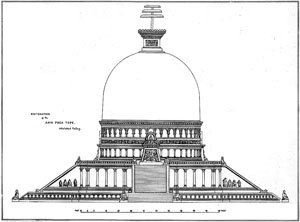

Sanchi is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located in 46 kilometres (29 mi) north-east of Bhopal, capital of Madhya Pradesh.

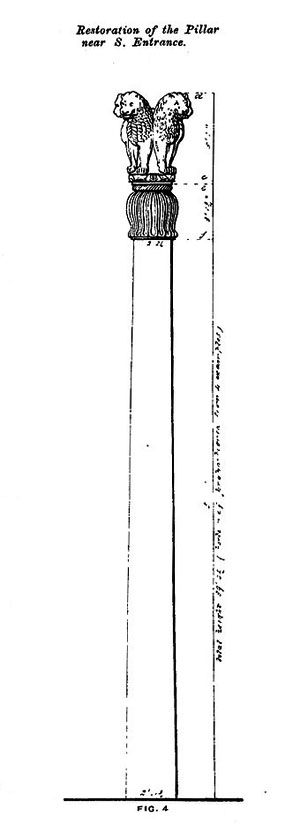

The Great Stupa at Sanchi is one of the oldest stone structures in India, and an important monument of Indian Architecture. It was originally commissioned by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka the Great in the 3rd century BCE. Its nucleus was a simple hemispherical brick structure built over the relics of the Buddha. It was crowned by the chhatri, a parasol-like structure symbolising high rank, which was intended to honour and shelter the relics. The original construction work of this stupa was overseen by Ashoka, whose wife Devi was the daughter of a merchant of nearby Vidisha. Sanchi was also her birthplace as well as the venue of her and Ashoka's wedding. In the 1st century BCE, four elaborately carved toranas (ornamental gateways) and a balustrade encircling the entire structure were added. The Sanchi Stupa built during Mauryan period was made of bricks. The composite flourished until the 11th century.

Sanchi is the center of a region with a number of stupas, all within a few miles of Sanchi, including Satdhara (9 km to the W of Sanchi, 40 stupas, the Relics of Sariputra and Mahamoggallana, now enshrined in the new Vihara, were unearthed there), Bhojpur (also called Morel Khurd, a fortified hilltop with 60 stupas) and Andher (respectively 11 km and 17 km SE of Sanchi), as well as Sonari (10 km SW of Sanchi). Further south, about 100 km away, is Saru Maru. Bharhut is 300 km to the northeast.

-- Sanchi, by Wikipedia

History of archaeological research in the Sanchi area

[x]

-- Buddhist Landscapes in Central India: Sanchi Hill and Archaeologies of Religious and Social Change, c. Third Century BC to Fifth Century AD, by Julia Shaw

Little Kushans (AD 270-350)

Following territory losses in the west (Bactria lost to the Kushano-Sasanians), and in the east (loss of Mathura to the Gupta Empire), several "Little Kushans" are known, who ruled locally in the area of Punjab with their capital at Taxila: Vasudeva II (270-300), Mahi (300-305), Shaka (305-335) and Kipunada (335-350).[80] They probably were vassals of the Gupta Empire, until the invasion of the Kidarites destroyed the last remains of Kushan rule.[80]

Kushan deities

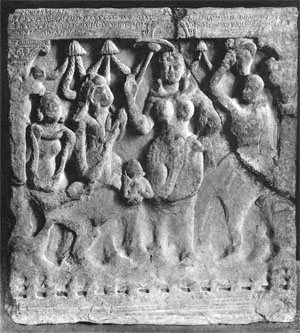

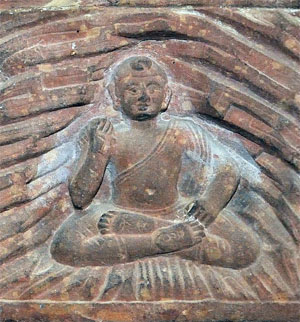

Kumara/Kartikeya with a Kushan devotee, 2nd century AD

Kushan prince, said to be Huvishka, making a donation to a Boddhisattva.[82]

Shiva Linga worshipped by Kushan devotees, circa 2nd century AD

The Kushan religious pantheon is extremely varied, as revealed by their coins that were made in gold, silver, and copper. These coins contained more than thirty different gods, belonging mainly to their own Iranian, as well as Greek and Indian worlds as well. Kushan coins had images of Kushan Kings, Buddha, and figures from the Indo-Aryan and Iranian pantheons.[83] Greek deities, with Greek names are represented on early coins. During Kanishka's reign, the language of the coinage changes to Bactrian (though it remained in Greek script for all kings). After Huvishka, only two divinities appear on the coins: Ardoxsho and Oesho (see details below).[84][85]

The Iranian entities depicted on coinage include:

• Ardoxsho (Αρδοχþο): Ashi Vanghuhi

• Ashaeixsho (Aþαειχþo, "Best righteousness"): Asha Vahishta

• Athsho (Αθþο, "The Royal fire"): Atar[84]

• Pharro (Φαρρο, "Royal splendour"): Khwarenah

• Lrooaspa (Λροοασπο): Drvaspa

• Manaobago (Μαναοβαγο): Vohu Manah[86]

• Mao (Μαο, the Lunar deity): Mah

• Mithro and variants (Μιθρο, Μιιρο, Μιορο, Μιυρο): Mithra

• Mozdooano (Μοζδοοανο, "Mazda the victorious?"): Mazda *vana[84][87]

• Nana (Νανα, Ναναια, Ναναϸαο): variations of pan-Asiatic Nana, Sogdian Nny, Anahita[84]

• Oado (Οαδο): Vata

• Oaxsho (Oαxþo): "Oxus"

• Ooromozdo (Ooρoμoζδο): Ahura Mazda

• Ořlagno (Οραλαγνο): Verethragna, the Iranian god of war

• Rishti (ΡΙϷΤΙ, "Uprightness"): Arshtat[84]

• Shaoreoro (ϷΑΟΡΗΟΡΟ, "Best royal power", Archetypal ruler): Khshathra Vairya[84]

• Tiero (Τιερο): Tir

Representation of entities from Greek mythology and Hellenistic syncretism are:

• Zeus (ZAOOY)[88]

• Helios (Ηλιος)

• Hephaistos (Ηφαηστος)

• Nike (Οα νηνδο)

• Selene (ϹΑΛΗΝΗ)

• Anemos (Ανημος)

• Erakilo (ΗΡΑΚΙΛΟ): Heracles

• Sarapo (ϹΑΡΑΠΟ): the Greco-Egyptian god Sarapis

The Indic entities represented on coinage include:[89]

• Boddo (Βοδδο): the Buddha

• Shakamano boddho (þακαμανο Βοδδο): Shakyamuni Buddha

• Metrago boddo (Μετραγο Βοδδο): the bodhisattava Maitreya

• Maaseno (Mαασηνo): Mahāsena

• Skando-Komaro (Σκανδo-koμαρo): Skanda-Kumara

• Bizago: Viśākha[89]

• Ommo: Umā, the consort of Siva.[89]

• Oesho (Οηϸο): long considered to represent Indic Shiva,[90][91][92] but also identified as Avestan Vayu conflated with Shiva.[93][94]

• Two copper coins of Huvishka bear a 'Ganesa' legend, but instead of depicting the typical theriomorphic figure of Ganesha, have a figure of an archer holding a full-length bow with string inwards and an arrow. This is typically a depiction of Rudra, but in the case of these two coins is generally assumed to represent Shiva.

Images of Kushan worshippers

Kushan worshipper with Zeus/Serapis/Ohrmazd, Bactria, 3rd century AD.[95]

Kushan worshipper with Pharro, Bactria, 3rd century AD.[95]

Kushan worshipper with Shiva/Oesho, Bactria, 3rd century AD.[95]

Shiva-Oesho wall painting with fragment of a worshipper, Bactria, 3rd century AD.[96]

Deities on Kushan coinage and seals

Mahasena on a coin of Huvishka

Four-faced Oesho

Rishti or Riom [97][98]

Manaobago

Pharro

Ardochsho

Oesho or Shiva

Oesho or Shiva with bull

Skanda and Visakha

Kushan Carnelian seal representing the "ΑΔϷΟ" (adsho Atar), with triratana symbol left, and Kanishka the Great's dynastic mark right

Coin of Kanishka I, with a depiction of the Buddha and legend "Boddo" in Greek script

Herakles.

Buddha

Coin of Vima Kadphises. Deity Oesho on the reverse, thought to be Shiva,[91][92][99] or the Zoroastrian Vayu.[100]

Kushans and Buddhism

The Ahin Posh stupa was dedicated in the 2nd century AD under the Kushans, and contained coins of Kushan and Roman Emperors.

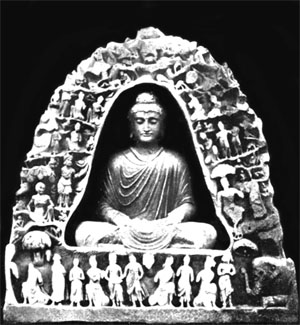

Early Mahayana Buddhist triad. From left to right, a Kushan devotee, Maitreya, the Buddha, Avalokitesvara, and a Buddhist monk. 2nd–3rd century, Gandhara

The Kushans inherited the Greco-Buddhist traditions of the Indo-Greek Kingdom they replaced, and their patronage of Buddhist institutions allowed them to grow as a commercial power.[101] Between the mid-1st century and the mid-3rd century, Buddhism, patronized by the Kushans, extended to China and other Asian countries through the Silk Road.[citation needed]

Kanishka is renowned in Buddhist tradition for having convened a great Buddhist council in Kashmir. Along with his predecessors in the region, the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Milinda) and the Indian emperors Ashoka and Harsha Vardhana, Kanishka is considered by Buddhism as one of its greatest benefactors.[citation needed]

During the 1st century AD, Buddhist books were being produced and carried by monks, and their trader patrons. Also, monasteries were being established along these land routes that went from China and other parts of Asia. With the development of Buddhist books, it caused a new written language called Gandhara. Gandhara consists of eastern Afghanistan and northern Pakistan. Scholars are said to have found many Buddhist scrolls that contained the Gandhari language.[102]

The reign of Huvishka corresponds to the first known epigraphic evidence of the Buddha Amitabha, on the bottom part of a 2nd-century statue which has been found in Govindo-Nagar, and now at the Mathura Museum. The statue is dated to "the 28th year of the reign of Huvishka", and dedicated to "Amitabha Buddha" by a family of merchants. There is also some evidence that Huvishka himself was a follower of Mahayana Buddhism. A Sanskrit manuscript fragment in the Schøyen Collection describes Huvishka as one who has "set forth in the Mahāyāna."[103]

The 12th century historical chronicle Rajatarangini mentions in detail the rule of the Kushan kings and their benevolence towards Buddhism:[104][105]

Then there ruled in this very land the founders of cities called after their own appellations the three kings named Huska, Juska and Kaniska (...) These kings albeit belonging to the Turkish race found refuge in acts of piety; they constructed in Suskaletra and other places monasteries, Caityas and similar edificies. During the glorious period of their regime the kingdom of Kashmir was for the most part an appanage of the Buddhists who had acquired lustre by renunciation. At this time since the Nirvana of the blessed Sakya Simha in this terrestrial world one hundred fifty years, it is said, had elapsed. And a Bodhisattva was in this country the sole supreme ruler of the land; he was the illustrious Nagarjuna who dwelt in Sadarhadvana.

— Rajatarangini (I168-I173)[105][106]