Part 2 of 2

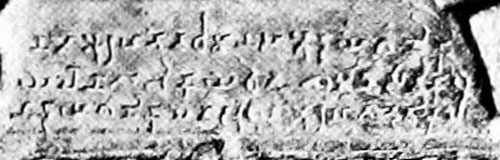

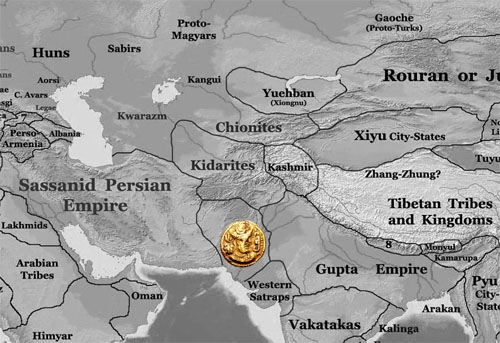

Indo-Scythians in Indian literature[x]File:AzesCamel.jpg

King Azes I on a camel, holding the ankus, and wearing a Phrygian cap. From some of his square coins.[46]

Main article: SakasThe Indo-Scythians were named "Shaka" in India, an extension on the name Saka used by the Persians to designate Scythians. From the time of the Mahabharata wars (1500-500 BCE) Shakas receive numerous mentions in texts like the Puranas, the Manusmriti, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Mahabhasiya of Patanjali, the Brhat Samhita of Vraha Mihira, the Kavyamimamsa, the Brihat-Katha-Manjari, the Katha-Saritsagara and several other old texts. They are described as part of an amalgam of other war-like tribes from the northwest.

"Degraded Kshatriyas" from the northwestThe Manusmriti, written about CE, groups the Shakas with the Yavanas, Kambojas, Paradas, Pahlavas, Kiratas and the Daradas etc..., and addresses them all as degraded warriors, or Kshatriyas (X/43-44). Anushasanaparava of the Mahabharata also views the Shakas, Kambojas, Yavanas etc. in the same light. Patanjali in his Mahabhasya regards the Shakas and Yavanas as pure Shudras (II.4.10).

The Vartika of the Katyayana informs us that the kings of the Shakas and the Yavanas, like those of the Kambojas, may also be addressed by their respective tribal names.

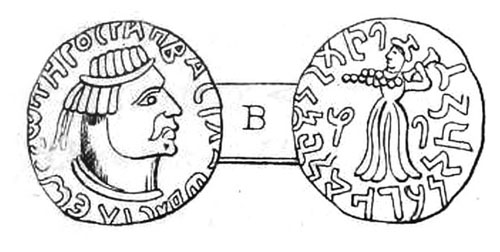

[x]File:Zeionises.jpg

Coin of Zeionises (circa 10 BCE - 10 CE).

Obv: King on horseback holding whip, with bow behind and Buddhist Triratna symbol.

Rev: Standing king, being crowned by the goddess Tyche.The Mahabharata also associates the Shakas with the Yavanas, Gandharas, Kambojas, Pahlavas, Tusharas, Sabaras, Barbaras etc and addresses them all as the Barbaric tribes of Uttarapatha. In another verse, the epic groups the Shakas Kambojas and Khashas and addresses them as the tribes from Udichya i.e. north division (5/169/20). Also, the Kishkindha Kanda of the Ramayana locates the Shakas, Kambojas, Yavanas and Paradas in the extreme north-west beyond the Himavat (i.e. Hindukush) (43/12).

The Udyogaparava of the Mahabharata (5/19/21-23) tells us that the composite army of the Kambojas, Yavanas and Shakas had participated in the Mahabharata war under the supreme command of Sudakshina Kamboja. The epic repeatedly applauds this composite army as being very fierce and wrathful.

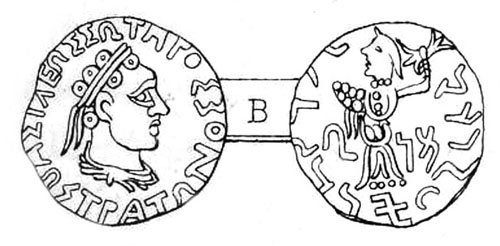

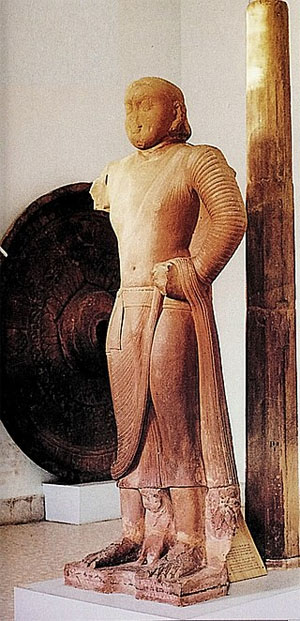

Invasion of India (180 BCE onward)[x]File:SpalirisesStandingInArmour.jpg

King Spalirises standing in armour. From his coins [1] and [2]. He holds the ankus in the right hand.The Vanaparava of the Mahabharata contains verses in the form of prophecy that the kings of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Bahlikas and Abhiras, etc. shall rule unrighteously in Kaliyuga (MBH 3/188/34-36).

This reference apparently alludes to the precarious political scenario following the collapse of Mauryan and Sunga dynasties in northern India and its occupation by foreign hordes of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas and Pahlavas.

Mahabharata referencesUdyoga Parva of Mahabharata groups the Shakas, Pahlavas, Paradas with the ‘’Kamboja-rishikas’’ and attests them as living on sea-shore in western India.[47] Again Udyoga Parava of Mahabharata lists the Shakas, Kambojas and the Khashas together and calls them as tribes of Udichya or Uttarapatha.[48] The Shanti Parva of Mahabharata also associates the Shakas with the Kambojas, Yavanas, Gandharas, Pahlavas, Tusharas, Sabaras, Barbaras, etc. and addresses them all as the Barbaric tribes of Uttarapatha.[49] More importantly, the Shaka army had joined the Kamboja army and together they had participated in the Kurukshetra war under single and supreme command of Sudakshina Kamboja.[50]

Ramayana referencesKishkindha Kanda Sarga 43 of Valmiki Ramayana collocates the Kambojas with the Shakas, Yavanas, Paradas and the Uttarakurus in the extreme northwest. The Yavanas are in (Bactria) and Kambojas in Tajikstan, the Paradas are on river Sailoda in Xinjiang province of China. The Uttarakurus lie beyond the Pamirs. The Shakas of the Ramayana obviously refer to the Shakas of Issyk-kul Lake lying beyond Suguda.[51] Adi-Kanda of the Ramayana,[52] tells us that the Kambojas, Shakas, Pahlavas and some other allied tribes from northwest were 'created' at the request of sage Vasishta by the Divine cow Shavala to defend Vasishta sage from the forces of king Vishwamitra (Dr B. C. Law). All these Ramayanic references seem to closely connect the Kambojas and the Shakas together.

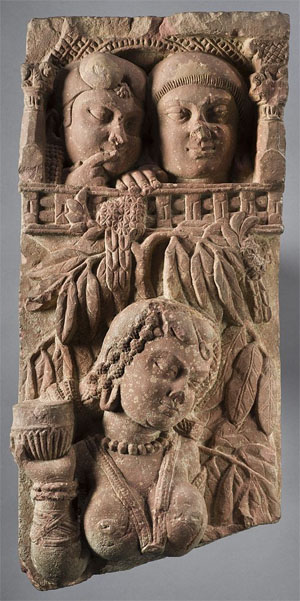

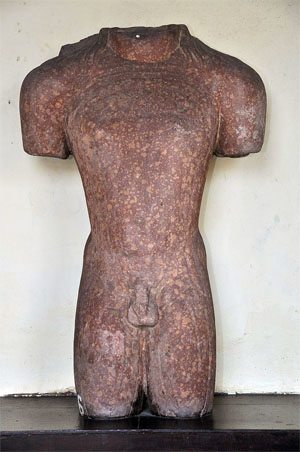

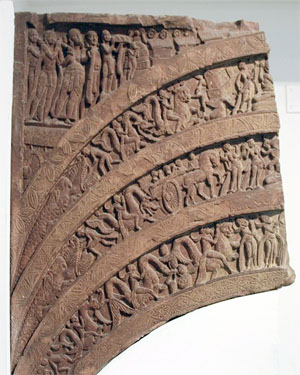

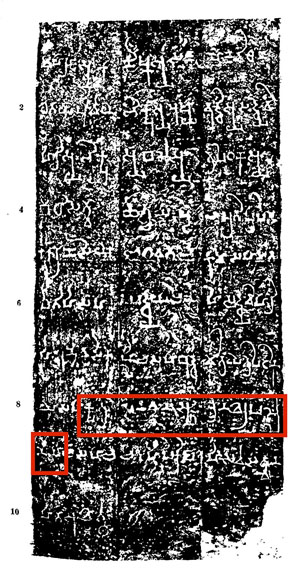

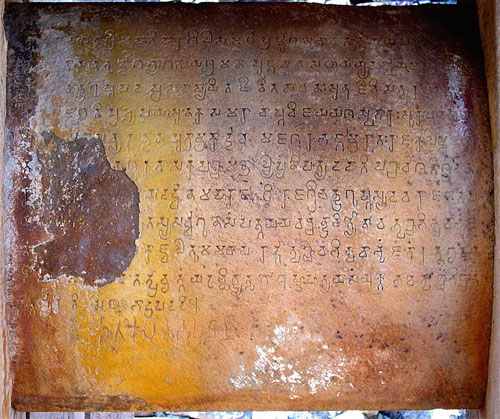

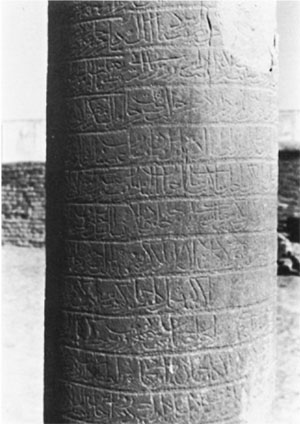

Puranic references[x]File:CastanaMathura.jpg

Statue of Chastana, found at the Temple of Mat, Mathura, together with statues of Kushan rulers. This statue suggests that the Western Satraps were vassals to the Kushans.Harivamsa Purana[53] and other Puranic literature[54] attest that Iksvaku king Bahu of Ayodhya was driven out of his dominions by Haihayas and Talajanghas with the assistance of Shakas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Pahlavas and Paradas Ayudhajivin Kshatriyas from Uttarapatha, popularly known as "five hordes" (ganah pāñca).[55]

Kalika Purana, one of the Upa-Puranas of the Hindus, refers to a war between Brahmanical king Kalika (supposed to be Pusyamitra Sunga) and Buddhist king Kali (supposed to be Maurya king Brihadratha (187-180 BCE)) and states the Shakas, Kambojas, Khasas, etc together as a powerful military allies of king Kali. The Purana further states that these Barbarians take the orders from their women.[56]

The Bhuvanakosha section of Puranic texts also lists the Kambojas with the Shakas, Paradas, Yavanas, Bahlikas, Sindhus, Soviras, Madrakas, Kekayas etc and place then all in the Udychya or northwest division.

Manusmiriti referenceManusmriti places the Shakas with the Kambojas, Yavanas, Pahlavas, Paradas and labels them all as degraded Kshatriyas defying the Brahmanical codes and rituals.[57]

Mahabharata, too similarly groups the Shakas with the Kambojas and Yavanas and states that they were originally noble Kshatriyas but got degraded to vrishala status on account of their non-observance of the sacred Brahmanical codes.[58]

Mudrarakshas referenceThe Buddhist drama Mudrarakshas by Visakhadutta and the Jaina works Parisishtaparvan refer to Chandragupta's alliance with Himalayan king Parvatka. This Himalayan alliance gave Chandragupta a powerful composite army made up of the north western tribes including the Shakas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Parasikas, Bahlikas etc.[59]

Other referencesIn the Brihat Katha of Pt. Kshmendra, Vedic king Vikramaditya had fought with the joint mlechcha forces of the Shakas, Kambojas, Hunas, Sabaras, Tusharas, Parasikas and had destroyed them completely.[60]

The Vartika of the Katyayana on Panini's Ashtadhyayi informs us that the kings of the Shakas and the Yavanas, like those of the Kambojas may similarly be addressed by their respective tribal names.[61]

There are numerous more similar references in ancient Sanskrit literature where the Kambojas and Shakas are listed together. All these references amply prove that the Shakas were closely allied to the Kambojas and both were living as close neighbors in the extreme of northwest division of ancient India.

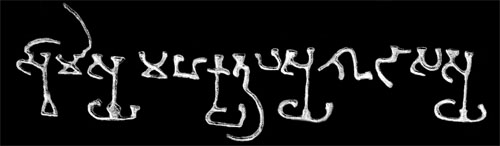

Sai-Wang Scythian hordes of Chipin or Kipin[x]File:AzesI.JPG

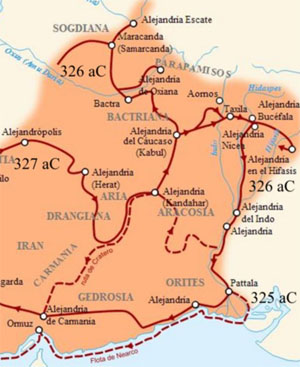

Coin of Azes II, with king seated, holding a drawn sword and a whip.A section of the Central Asian Scythians (under Sai-Wang) is said to have taken southerly direction and after passing through the Pamirs it entered the Chipin or Kipin after crossing the Hasuna-tu (Hanging Pass) located above the valley of Kanda in Swat country.[62] Chipin has been identified by Dr Pelliot, Dr Bagchi, Dr Raychaudhury and some others with Kashmir[63] while other scholars identify it with Kapisha (Kafirstan).[64][65] The Sai-Wang had established his kingdom in Kipin. Dr S. Konow interprets the Sai-Wang as Saka Murunda of Indian literature, Murunda being equal to Wang i.e. king, master or lord,[66] but prof Bagchi who takes the word Wang in the sense of the king of the Scythians but he distinguishes the Sai Sakas from the Murunda Sakas.[67] There are reasons to believe that Sai Scythians were Kamboja Scythians and therefore Sai-Wang belonged to the Scythianised Kambojas (i.e. Parama-Kambojas) of the Transoxiana region and came back to settle among his own stock after being evicted from his ancestral land located in Scythia or Shakadvipa. King Moga or Maues could have belonged to this group of Scythians who had migrated from the Sai country (Central Asia) to Chipin.[68] The Mathura Lion Capital inscriptions attest that the members of the family of king Moga (q.v.) had last name Kamuia or Kamuio (q.v) which Khroshthi term has been identified by scholars with Sanskrit Kamboja or Kambojaka.[69] Thus, Sai-Wang and his migrant hordes which came to settle in Kabol valley in Kapisha may indeed have been from the transoxian Parama Kambojas living in Shakadvipa or Scythian land.[70]

Establishment of Mlechcha Kingdoms in Northern India[x]File:BalaramaMauesCoin1stCenturyBCE.jpg

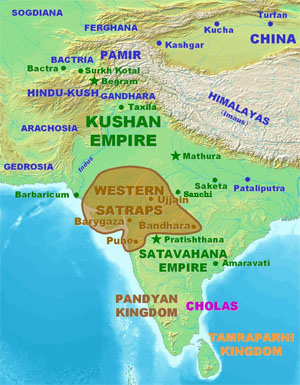

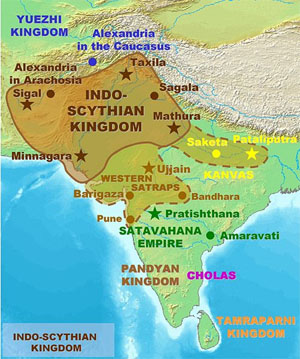

Coin of Maues depicting Balarama, 1st century BCE. British Museum.The mixed Scythian hordes that migrated to Drangiana and surrounding regions, later spread further into north and south-west India via the lower Indus valley. Their migration spread into Sovira, Gujarat, Rajasthan and northern India, including kingdoms in the Indian mainland.

There are important references to the warring Mleccha hordes of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas and Pahlavas in the Bala Kanda of the Valmiki Ramayana also[71].

Leading Indologists like Dr H. C. Raychadhury glimpses in these verses the struggles between the Hindus and the invading hordes of Mlechcha barbarians from the northwest. The time frame for these struggles is the second century BCE onwards. Dr Raychadhury fixes the date of the present version of the Valmiki Ramayana around or after the second century CE.[72]

This picture presented by the Ramayana probably refers to the political scenario that emerged when the mixed hordes descended from Sakasthan and advanced into the lower Indus valley via Bolan Pass and beyond into the Indian mainland. It refers to the hordes' struggle to seize political control of Sovira, Gujarat, Rajasthan, Punjab, Malwa, Maharashtra and further areas of eastern, central and southern India.

Mahabharata too furnishes a veiled hint about the invasion of the mixed hordes from the northwest. Vanaparava by Mahabharata contains verses in the form of prophecy deploring that "......the Mlechha (barbaric) kings of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Bahlikas, etc shall rule the earth (i.e India) un-rightously in Kaliyuga..".[73]

According to Dr H. C. Ray Chaudhury, this is too clear a statement to be ignored or explained away.

Mahabharata's epic reference apparently alludes to the chaotic politics which followed the collapse of the Mauryan and Sunga dynasties in northern India and the area's subsequent occupation by foreign hordes of the Saka, Yavana, Kamboja, Pahlavas, Bahlika, Shudra and Rishika tribes from the northwest.

See also: Migration of Kambojas

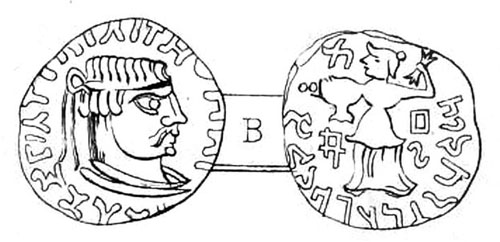

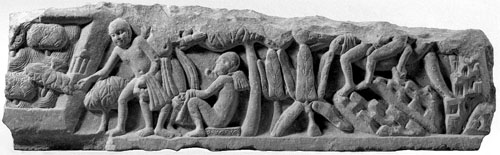

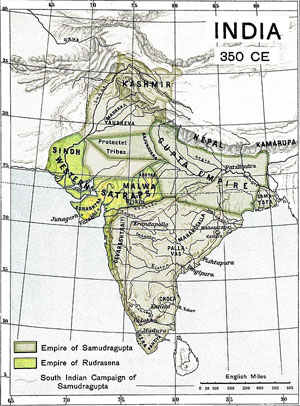

Evidence about joint invasions[x]File:AzesIIDepiction.jpg

Equipment of the Indo-Scythian king Azes II (r.35-12 BCE), as shown on his clearest coins.[74] He wears a type of Phrygian cap with flaps, and a web-like armour (a cataphract), on top of a thick tunic. He holds a whip in the right hand. The two threads behind his back are probably a sign of his royalty. The upper end of a recurve bow appears from the left side of the saddle (click image for reference).The clans of the Shakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Pahlavas, Paradas, etc had been invading India from Central Asia many years before the Christian era. These peoples were all absorbed into the community of Kshatriyas of mainstream Indian society.[75]

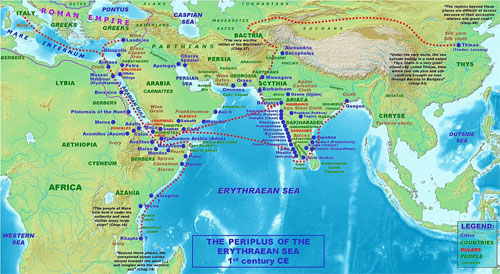

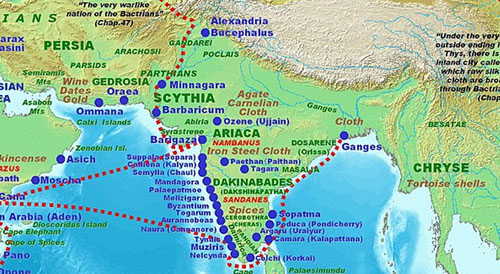

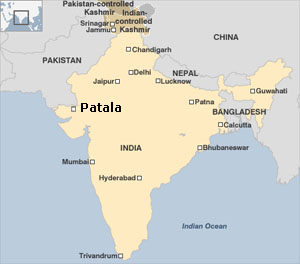

The Shakas were formerly a people of trans-Hemodos region---the Shakadvipa of the Puranas or the Scythia of the classical writings. Isidor of Charax (beginning of first c AD) attests them in Sakastana (modern Seistan). First century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (c AD 70-80) also attests a Scythian district in lower Indus with Minnagra as its capital. Ptolemy (c AD 140) also attests Indo-Scythia in south-western India which comprised Patalene, Abhira and the Surastrene (Saurashtra) territories.

The second century BCE Scythian invasion of India, was in all probability carried out jointly by the Sakas, Pahlavas, Kambojas, Paradas, Rishikas and other allied tribes from the northwest.[76] As a result, groups of these people who had originally lived in the northwest before the Christian era, were also found to have lived in southwest India in post-Christian times. All these groups of north-western peoples apparently entered Indian mainland following the Scythian invasion of India.

Main Indo-Scythian rulers

Northwestern India:• Maues, c. 90-60 BCE

• Vonones, c. 75-65 BCE

• Spalahores, c. 75-65 BCE, satrap and brother of king Vonones, and probably the later king Spalirises.

• Spalirises, c. 60-57 BCE, king and brother of king Vonones.

• Spalagadames c.50 BCE, satrap, and son of Spalahores.

• Azes I, c. 57-35 BCE

• Azilises, c. 57-35 BCE

• Azes II, c. 35-12 BCE

• Zeionises, c.10 BCE-10 CE

• Kharahostes, c.10 BCE- 10 CE

• Indravarman

• Hajatria

Kshaharatas:Main article: Kshaharatas

• Liaka Kusuluka, satrap of Chuksa

• Kusulaka Patika, satrap of Chuksa and son of Liaka Kusulaka

• Abhiraka

• Bhumaka

• Nahapana (founder of the Western Satraps)

Apracarajas (Bajaur area):Main article: Apracarajas

• Vijayamitra (12 BCE - 15 CE)

• Itravasu (c.20 CE)

• Aspavarma (15 - 45 CE)

Paratarajas:Main article: Paratarajas

• Kuvhusuvhume

• Spajhana

• Spajhayam

• Bhimajhuna

• Yolamira, son of Bagavera (2nd century)

• Arjuna, son of Yolamira (2nd century)

• Karyyanapa

• Hvaramira, another son of Yolamira(2nd century)

• Mirahvara, son of Hvaramira (2nd century)

• Miratakhma, another son of Hvaramira (2nd century)

"Northern Satraps" (Mathura area):• Hagamasha (satrap, 1st century BCE)

• Hagana (satrap, 1st century BCE)

• Rajuvula, c.10 CE (Great Satrap)

• Sodasa, son of Rajuvula

• "Great Satrap" Kharapallana (circa 130 CE)

• "Satrap" Vanaspara (circa 130 CE)

Minor local rulers:• Bhadayasa

• Mamvadi

• Arsakes

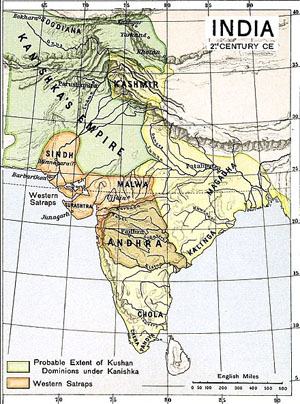

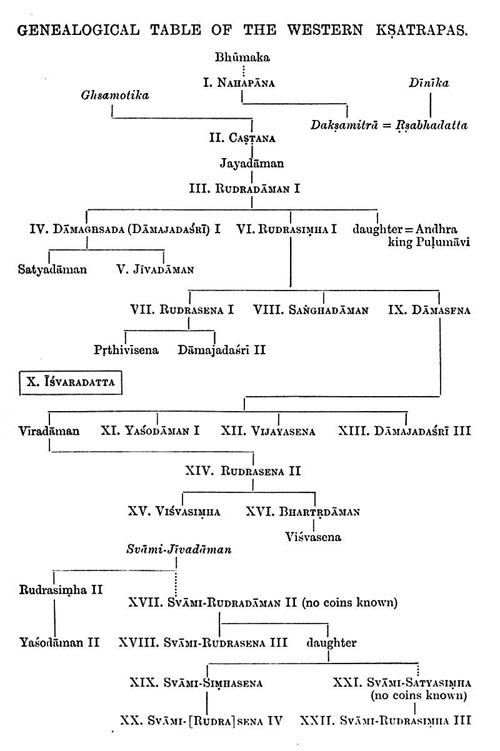

Western SatrapsMain article: Western Satraps

• Nahapana (119-124) 50px

• Chastana (c 120), son of Ghsamotika 50px

• Jayadaman, son of Chastana

• Rudradaman I (c 130-150), son of Jayadaman 50px

• Damajadasri I (170-175)

• Jivadaman (175 d 199)

• Rudrasimha I (175-188 d 197)

• Isvaradatta (188-191)

• Rudrasimha I (restored) (191-197)

• Jivadaman (restored) (197-199)

• Rudrasena I (200-222)

• Samghadaman (222-223)

• Damasena (223-232)

• Damajadasri II (232-239) with

• Viradaman (234-238)

• Yasodaman I (239)

• Vijayasena (239-250)

• Damajadasri III (251-255)

• Rudrasena II (255-277)

• Visvasimha (277-282)

• Bhratadarman (282-295)50px with

• Visvasena (293-304)

• Rudrasimha II, son of Lord (Svami) Jivadaman (304-348) with

• Yasodaman II (317-332)

• Rudradaman II (332-348)

• Rudrasena III (348-380)

• Simhasena (380- ?)

• Rudrasena IV (382-388)

• Rudrasimha III (388-395)50px

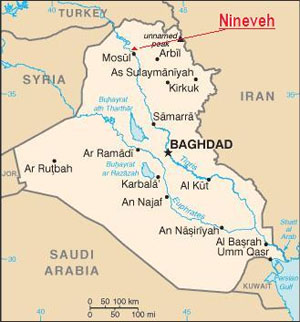

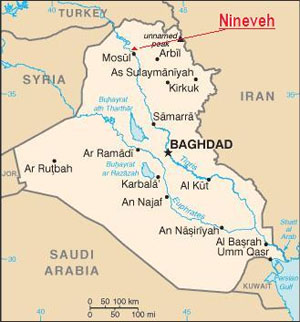

Ch.8 Description of Darius-III's Army at Arbela against Alexander  Map - Location of Arbīl

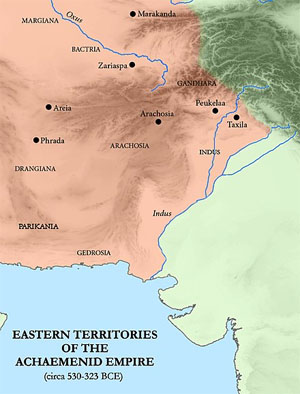

Map - Location of ArbīlThey come to the aid of Darius-III (the last king of the Achaemenid Empire of Persia) and were part of alliance in the battle of Gaugamela (331 BC) formed by Darius-III in war against Alexander the Great at Arbela, now known as Arbil, which is the capital of Kurdistan Region in northern Iraq.

Arrian[77] writes....Alexander therefore took the royal squadron of cavalry, and one squadron of the Companions, together with the Paeonian scouts, and marched with all speed; having ordered the rest of his army to follow at leisure. The Persian cavalry, seeing Alexander, advancing quickly, began to flee with all their might. Though he pressed close upon them in pursuit, most of them escaped; but a few, whose horses were fatigued by the flight, were slain, others were taken prisoners, horses and all. From these they ascertained that Darius with a large force was not far off. For the Indians who were conterminous with the Bactrians, as also the Bactrians themselves and the Sogdianians had come to the aid of Darius, all being under the command of Bessus, the viceroy of the land of Bactria. They were accompanied by the Sacians, a Scythian tribe belonging to the Scythians who dwell in Asia.[1] These were not subject to Bessus, but were in alliance with Darius. They were commanded by Mavaces, and were horse-bowmen. Barsaentes, the viceroy of Arachotia, led the Arachotians[2] and the men who were called mountaineer Indians. Satibarzanes, the viceroy of Areia, led the Areians,[3] as did Phrataphernes the Parthians, Hyrcanians, and Tapurians,[4] all of whom were horsemen. Atropates commanded the Medes, with whom were arrayed the Cadusians, Albanians, and Sacesinians.[5] The men who dwelt near the Red Sea[6] were marshalled by Ocondobates, Ariobarzanes, and Otanes. The Uxians and Susianians[7] acknowledged Oxathres son of Aboulites as their leader, and the Babylonians were commanded by Boupares. The Carians who had been deported into central Asia, and the Sitacenians[8] had been placed in the same ranks as the Babylonians. The Armenians were commanded by Orontes and Mithraustes, and the Cappadocians by Ariaoes. The Syrians from the vale between Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon (i.e. Coele-Syria) and the men of Syria which lies between the rivers[9] were led by Mazaeus. The whole army of Darius was said to contain 40,000 cavalry, 1,000,000 infantry, and 200 scythe-bearing chariots.[10] There were only a few elephants, about fifteen in number, belonging to the Indians who live this side of the Indus.[11] With these forces Darius had encamped at Gaugamela, near the river Bumodus, about 600 stades distant from the city of Arbela, in a district everywhere level;[12] for whatever ground thereabouts was unlevel and unfit for the evolutions of cavalry, had long before been levelled by the Persians, and made fit for the easy rolling of chariots and for the galloping of horses. For there were some who persuaded Darius that he had forsooth got the worst of it in the battle fought at Issus, from the narrowness of the battle-field; and this he was easily induced to believe.

________________________________________

1. Cf. Aelian (Varia Historia, xii. 38).

2. Arachosia comprised what is now the south-east part of Afghanistan and the north-east part of Beloochistan.

3. Aria comprised the west and north-west part of Afghanistan and the east part of Khorasan.

4. Parthia is the modern Khorasan. Hyrcania was the country south and south-east of the Caspian Sea. The Tapurians dwelt in the north of Media, on the borders of Parthia between the Caspian passes. Cf. Ammianus, xxiii. 6.

5. The Cadusians lived south-west of the Caspian, the Albanians on the west of the same sea, in the south-east part of Georgia, and the Sacesinians in the north-east of Armenia, on the river Kur.

6. "The Red Sea was the name originally given to the whole expanse of sea to the west of India as far as Africa. The name was subsequently given to the Arabian Gulf exclusively. In Hebrew it is called Yam-Suph (Sea of Sedge, or a seaweed resembling wool). The Egyptians called it the Sea of Weeds.

7. The Uxians occupied the north-west of Persis, and Susiana was the country to the north and west of Persis.

8. The Sitacenians lived in the south of Assyria. ἐτετάχατο. is the Ionic form for τεταγμἑνοι ἦσαν.

9. The Greeks called this country Mesopotamia because it lies between the rivers Euphrates and Tigris. In the Bible it is called Paddan-Aram (the plain of Aram, which is the Hebrew name of Syria). In Gen. xlviii. 7 it is called merely Paddan, the plain. In Hos. xii. 12, it is called the field of Aram, or, as our Bible has it, the country of Syria. Elsewhere in the Bible it is called Aram-naharaim, Aram of the two rivers, which the Greeks translated Mesopotamia. It is called "the Island," by Arabian geographers.

10. Curtius (iv. 35 and 45) states that Darius had 200,000 infantry, 45,000 cavalry, and 200 scythed chariots; Diodorus (xvii. 53) says, 800,000 infantry, 200,000 cavalry, and 200 scythed chariots; Justin (xi. 12) gives 400,000 foot and 100,000 horse; and Plutarch (Alex., 31) speaks of a million of men. For the chariots cf. Xenophon (Anab., i 8, 10); Livy, xxxvii. 41.

11. This is the first instance on record of the employment of elephants in battle.

12. This river is now called Ghasir, a tributary of the Great Zab. The village Gaugamela was in the district of Assyria called Aturia, about 69 miles from the city of Arbela, now called Erbil.

p.154-157

In PuranasVishnu Purana[78] gives list of Kings who ruled Magadha. ...After these, various races will reign, as seven Ábhíras, ten Garddhabas, sixteen Śakas, eight Yavanas, fourteen Tusháras, thirteen Mundas, eleven Maunas, altogether seventy-nine princes , who will be sovereigns of the earth for one thousand three hundred and ninety years.

• Ábhíras, 7, M.; 10, V;

• Avabhriti, 7, Bhág.

• Garddabhins, 10, M. V. Bhág.

• Śakas, 18, M. V.;

• Kankas, 16, Bhág.

• Yavanas, 8, M. V. Bhág.

• Tusháras, 14, M. V.;

• Tushkaras, 14, Bhág.

• Marúńdas, 13, V.;

• Purúńd́as, 13, M.;

• Surúńdas, 10, Bhág.

• Maunas, 18, V.;

• Húńas, 19, M.;

• Maulas, 11, Bhág.

Total--85 kings, Váyu; 89, Matsya; 76, and 1399 years, Bhág.

Footnotes1. Jat History Dalip Singh Ahlawat/Chapter IV, p.341

2. Origin of the Saka Races - Collapse of the Brahminist Empire (Chapter 3) | by Khshatrapa Gandasa

3. Trevaskis (p. 40.)

4. Archaeological Survey Report of India, Vol II, Vanaras, p. 193.

5. Kumar, Raj (2008). Encyclopaedia Of Untouchables Ancient, Medieval And Modern. Gyan Publishing House. p. 144. ISBN 8178356643, 9788178356648

6. Przyluski

7. Tarn

8. An Inquiry Into the Ethnography of Afghanistan By H. W. Bellew, The Oriental University Institute, Woking, 1891, p.185

9. An Inquiry Into the Ethnography of Afghanistan By H. W. Bellew, The Oriental University Institute, Woking, 1891, p.161

10. Scythians - Who Were the Scythians

11. Scythians - Who Were the Scythians

12. Scythians - Livius

13. Scythian (Skythian) : Etymology

14. Ma-Twan-Lin's Chinese Encyclopedia of the 13th century AD states: "In ancient times, the Hiung-nu having defeated the Yue-chi, the latter went to the west and dwelt among the Ta-hia and the king of Sai went to southwards to live in Kipin. The tribes of Sai divided and dispersed so as to form here and there different kingdoms." Shin-chi, Chapter 123; Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 691; History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, p 122.

15. Ch'ien Han-Shu's History of the first Han Dynasty says: “Formerly when the Hiung-nu conquered the Ta Yue-chi (Great Yue-chi), the latter migrated to the west and subjugated the Ta-hia whereupon the Sai-Wang went to South and ruled over Kipin” (Ch'ien Han-shu, Chapter 96A). The territory of the Wu-sun was originally the country of the Sai (Ch'ien Han-shu, Chapter 96B). The name of the Sai-Wang ruler is not given. Some scholars identify the Ta-hia in these records as Bactria(Cambridge History of India, Vol I, p 511, E. J. Rapson (Ed)).

16. The Age of Imperial Unity, History and Culture of Indian People, p122, (Ed.) Dr R. C. Majumdar, Dr A. D. Pusalkar.

17. Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, pp 296-309, Dr J. L. Kamboj.

18. The joint resistance of the Saka, Kamboja Parama-Kamboja), Rishika, Loha, Parada and Bahlikas tribes to the Yue-chi and migration south-west together reflected the strong ties between the neighbouring tribes since remote antiquity. Early Indian literature records military alliances between the Sakas, Kambojas, Pahlavas and Paradas. The ancient Puranic traditions mentions several joint invasions of India by the Scythians. The conflict between the Bahu-Sagara of India and the Haihaya-Kamboja-Saka-Pahlava-Yavana-Parada is well known as the war fought by "five hordes" (pāňca-ganha). The Sakas, Yavanas, Tusharas and Kambojas also fought the Kurukshetra war under the command of Sudakshina Kamboja. The Valmiki Ramayana also attests that the Sakas, Kambojas, Pahlavas and Yavanas fought together against the Vedic, Hindu king Vishwamitra of Kanauj.

19. Y-STR Haplogroup Diversity in the Jat Population Reveals Several Different Ancient Origins

20. The Jats:Their Origin, Antiquity and Migrations/The identification of the Jats,pp. 325-326

21. Justin XL.II.2

22. Isodor of Charax, Sathmoi Parthikoi, 18.

23. Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 693.

24. The Sakas in India, p 14, Dr S. Chattopadhyaya; The Development of Khroshthi Script, p 77, Dr C. C. Dasgupta; Hellenism in Ancient India, p 120, Dr G. N. Banerjee; Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, p 308, Dr J. L. Kamboj; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p 169, S Kirpal Singh etc

25. Journal of Bohar and Orissa Research Society, Vol XVI, Parts III and IV, 1930, p 229; Hindu Polity, 1943, p 144, Dr K. P. Jayswal

26. Parthian stations

27. V. S. Agrawala: India as Known to Panini, 1953, p.68-69

28. Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, 38

29. "The dynastic art of the Kushans", John Rosenfield, p.130

30. Kshatrapasa pra Kharaostasa Artasa putrasa. See: Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 398, Dr H. C. Raychaudhury, Dr B. N. Mukerjee; Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, p 307, Dr J. L. Kamboj; Ancient India, 1956, p 220-221, Dr R. K. Mukerjee; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p 168, S Kirpal Singh.

31. Ancient India, pp 220-221, Dr R. k. Mukerjee; Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, pp 168-169, S Kirpal Singh; Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, p p 306-09, Dr J. L. Kamboj; Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol II, Part 1, p 36, D S Konow

32. Dr Jayaswal writes:“Mathura was under outlandish people like the Yavanas and Kambojas... who had a special mode of fighting" (Manu and Yajnavalkya, Dr K. P. Jayswal); See also: Indian Historical Quarterly, XXVI-2, p 124. Prof Shashi Asthana comments: "Epic Mahabharata refers to the siege of Mathura by the Yavanas and Kambojas (see: History and Archaeology of India's Contacts with Other Countries, from Earliest Times to 300 B.C., 1976, p 153, Shashi Asthana). Dr Buddha Prakash observes: "Along with the Sakas, the Kambojas had also entered Indian mainland and spread into whole of North India, especially in Panjab and Uttar Pradesh. Mahabharata contains references to Yavanas and Kambojas having conquered Mathura (12/105/5)....There is also a reference to the Kambojas in the Mathura Lion Capital inscriptions of SakaSatrap (Kshatrapa) Rajuvula found in Mathura " (India and the World, p 154, Dr Buddha Parkash); cf: Ancient India, 1956, p 220, Dr R. K. Mukerjee

33. Mahabharata 12.101.5.

34. Source: "A Catalogue of the Indian Coins in the British Museum. Andhras etc..." Rapson, p ciii

35. A gap in Puranic history

36. Francine Tissot "Gandhara", p74

37. Wilcox and McBride (1986), p. 12.

38. Photographic reference here.

39. "Let us remind that in Sirkap, stone palettes were found at all excavated levels. On the contrary, neither Bhir-Mound, the Maurya city preceding Sirkap on the Taxila site, nor Sirsukh, the Kushan city succeeding her, did deliver any stone palettes during their excavations", in "Les palettes du Gandhara", p89. "The terminal point after which such palettes are not manufactured anymore is probably located during the Kushan period. In effect, neither Mathura nor Taxila (although the Sirsukh had only been little excavated), nor Begram, nor Surkh Kotal, neither the great Kushan archaeological sites of Soviet Central Asia or Afghanistan have yielded such objects. Only four palettes have been found in Kushan-period archaeological sites. They come from secondary sites, such as Garav Kala and Ajvadz in Soviet Tajikistan and Jhukar, in the Indus Valley, and Dalverzin Tepe. They are rather roughly made." In "Les Palettes du Gandhara", Henri-Paul Francfort, p91. (in French in the original)

40. Source:"Butkara I", Faccena

41. "Gandhara" Francine Tissot

42. The Turin City Museum of Ancient Art Text and photographic reference: Terre Lontane > O2

43. For the pilaster showing a man in Greek dress Image:ButkaraPilaster.jpg.

44. Facenna, "Sculptures from the sacred area of Butkara I", plate CCCLXXI. The relief is this one, showing Indo-Scythians dancing and reveling, with on the back side a relief of a standing Buddha (not shown).

45. Faccenna, "Sculptures from the sacred area of Butkara I", plate CCCLXXII

46. Coin reference, also, also, also.

47. .

Shakanam pahlavana.n cha daradanam cha ye nripah

Kambojarishika ye cha pashchimanupakash cha ye

(MBH 5/5/15.)

48. Udichya Kamboja Shakaih Khashaish cha (MBH 5/159/20) .

49. Mahabharata 12.65.13-14

50.

vibhuuamana vatena bahurupa ivambudah/

Sudakshinashcha Kambojo yavanaishcha shakaistatha|| 21

upajagama kauravyamakshauhinya visham pate |

tasya sena samavayah shalabhanamivababhau ||22

(MBH 5/19/21-22).

51.

Kaamboja Yavanaan caiva Shakaan pattanaani ca |

Anvikshya Varadaan caiva Himavantam vicinvatha || 12 ||

(Ramayana 4.43.12).

52. Ramayana 1/55/2-3

53. 14.01-19

54. e.g Vayu Purana 88.127-43; Brahma Purana (8.35-51); Brahamanda Purana (3.63.123-141); Shiva Purana (7.61.23); Vishnu Purana (5.3.15-21), Padama Purana (6.21.16-33) etc etc.

55. Ete hyapi 'ganah pancha' haihayarthe parakraman... (Brahama Purana 8.36).

56. Ref: Kalika Purana, III(6), 22-40).

57. Manusmiriti X.43-44

58. Mahabharata 13/33/20-2.

59. Mudrarakshas, II.

60. Brhatkatha 10.1.285-86

61. J Kambojadhybya iti vachyam Vartika (Katyayana); See: Some Kshatriya Tribes of Ancient India, 1924, p 234, Dr B. C. Law

62. Serindia, Vol I, 1980 Edition, p 8, M. A. Stein

63. Op cit p 693, Dr H. C. Raychaudhury, Dr B. N. Mukerjee; Early History of North India, p 3, Dr S. Chattopadhyava; India and Central Asia, p 126, Dr P. C. Bagchi

64. Epigraphia Indiaca XIV, p 291 Dr S Konow; Greeks in Bactria and India, p 473, fn, Dr W. W. Taran; Yuan Chwang I, p 259-60, Watters; Comprehensive History of India, Vol I, p 189, Dr N. K. Sastri; History and Culture of Indian People, The Age of Imperial Unity, 122; History and Culture of Indian People, Classical Age, p 617, Dr R. C. Majumdar, Dr A. D. Pusalkar.

65. Scholars like Dr E. J. Rapson, Dr L. Petech etc also connect Kipin with Kapisha. Dr Levi holds that prior to 600 AD, Kipin denoted Kashmir, but after this it implied Kapisha See Discussion in The Classical Age, p 671.

66. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, II. 1. XX f; cf: Early History of North India, pp 54, Dr S Chattopadhyaya.

67. India and Central Asia, 1955, p 124, Dr P. C. Bagch; Geographical Data in Early Puranas, 1972, p 47, Dr M. R. Singh.

68. See: Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p fn 13, Dr B. N. Mukerjee; Chilas, Islamabad, 1983, no 72, 78, 85, pp 98, 102, A. H. Dani

69. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol II, Part 1, p xxxvi, see also p 36; Bihar and Orisaa Research Society, Vol XVI, 1930, part III and IV, p 229 etc

70. J Dr Buddha Prakash has identified some of the modern castesof the Punjab with ancient tribes which came from Central Asiaand settled in India. Dr Prakash has correctly related the modern Kamboj/Kamboh to the Iranian Kambojas who belonged to the domain of Kumuda-dvipa of the Puranas or the Komdei of Ptolemy’s Geography (Political and Social Movements in Ancient Punjab, Dr. Buddha Prakash; See: Studies in Indian History and Civilization, Agra, p 351; India and the World, 1964, p 71, Dr Buddha Prakash; The Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p 92, 59/159, S. Kirpal Singh). This was the habitat of the Parama Kambojas referred to in Mahabharata (MBH 2.27.25) and were located in Transoxianaterritory in Shakadvipa (Ibid, S Kirpal Singh). Dr Buddha Prakash further states that the people of Soi clan of Punjab are descended from the Sai-Wang (Saka). It is not mere coincidence that modern Kamboj of Punjab have prominent clan names like Soi, Asoi and Sahi/Shahi: See link for Kamboj clan names: [[[kamboj#List of Kamboj Gotras .28clans.29|http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kamboj#List of Kamboj Gotras .28clans.29]]]. Clan name Soi can be linked to Sai-Wang as Dr Buddh Prakash has shown. Similarly, Asoi clan of Kamboj can also be very well related to or connected with Asii or Asio of Strabo (See: Strabo XI.8,2.) which clan name undoubtedly represents people connected with horse-culture, which the ancient Kambojas pre-eminently were. The above evidence thus again points to a connection of the Sai/Sai-wangmentioned in Chinese chronicles and the Asii/Asio clan mentioned in Strabo’s accounts with the Scythian Kambojas i.e.Parama Kambojas.

71.

taih asit samvrita bhuumih Shakaih-Yavana mishritaih || 1.54-21 ||

taih taih Yavana-Kamboja barbarah ca akulii kritaah || 1-54-23 ||

tasya humkaarato jatah Kamboja ravi sannibhah |

udhasah tu atha sanjatah Pahlavah shastra panayah || 1-55-2 ||

yoni deshaat ca Yavanah Shakri deshat Shakah tathaa |

roma kupesu Mlecchah ca Haritah sa Kiratakah || 1-55-3 ||.

72. Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 3-4.

73.

viparite tada loke purvarupa.n kshayasya tat || 34 ||

bahavo mechchha rajanah prithivyam manujadhipa |

mithyanushasinah papa mrishavadaparayanah || 35 ||

Andhrah Shakah Pulindashcha Yavanashcha naradhipah |

Kamboja Bahlikah Shudrastathabhira narottama || 36 ||

— (MBH 3.188.34-36).

74. Coin source

75. History and Culture of Indian People, The Vedic Age, pp 286-87, 313-14.

76. cf: Interaction Between India and Western World, pp 75-93, H. G. Rawlinson; Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, p 306; cf: India and the World, p 154, Dr Buddha Parkash; cf: Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, p 159-60, 168-69, S Kirpal Singh.

77. The Anabasis of Alexander/3a, Ch.8

78. Vishnu Purana/Book IV:Chapter XXIV pp.474-476

References• Bailey, H. W. 1958. "Languages of the Saka." Handbuch der Orientalistik, I. Abt., 4. Bd., I. Absch., Leiden-Köln. 1958.

• Faccenna D., "Sculptures from the sacred area of Butkara I", Istituto Poligrafico Dello Stato, Libreria Dello Stato, Rome, 1964.

• Foucher, M. A. 1901. "Notes sur la geographie ancienne du Gandhâra (commentaire à un chaptaire de Hiuen-Tsang)." BEFEO No. 4, Oct. 1901, pp. 322–369.

• Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Paris, UNESCO Publishing.

• Hill, John E. 2004. The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu. Draft annotated English translation.[3]

• Hill, John E. 2004. The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 CE. Draft annotated English translation. [4]

• Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

• Konow, Sten. Editor. 1929. Kharoshthī Inscriptions with Exception of those of Asoka. Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol. II, Part I. Reprint: Indological Book House, Varanasi, 1969.

• Litvinsky, B. A., ed., 1996. History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume III. The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Paris, UNESCO Publishing.

• Liu, Xinru 2001 “Migration and Settlement of the Yuezhi-Kushan: Interaction and Interdependence of Nomadic and Sedentary Societies.” Journal of World History, Volume 12, No. 2, Fall 2001. University of Hawaii Press, pp. 261–292. [5].

• Bulletin of the Asia Institute: The Archaeology and Art of Central Asia. Studies From the Former Soviet Union. New Series. Edited by B. A. Litvinskii and Carol Altman Bromberg. Translation directed by Mary Fleming Zirin. Vol. 8, (1994), pp. 37-46.

• Pulleyblank, Edwin G. 1970. "The Wu-sun and Sakas and the Yüeh-chih Migration." Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 33 (1970), pp. 154-160.

• Puri, B. N. 1994. "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians." In: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Volume II. The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 B.C. to A.D. 250. Harmatta, János, ed., 1994. Paris: UNESCO Publishing, pp. 191-207.

• Thomas, F. W. 1906. "Sakastana." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1906), pp. 181-216.

• Watson, Burton. Trans. 1961. Records of the Grand Historian of China: Translated from the Shih chi of Ssu-ma Ch'ien. Chapter 123: The Account of Ta-yüan, p. 265. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08167-7

• Yu, Taishan. 1998. A Study of Saka History. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 80. July, 1998. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

• Yu, Taishan. 2000. A Hypothesis about the Source of the Sai Tribes. Sino-Platonic Papers No. 106. September, 2000. Dept. of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Pennsylvania.

• Political History of ancient India, 1996, Dr H. C. raychaudhury

• Hindu Polity, A Constitutional history of India in Hindu Times, 1978, Dr K. P. Jayswal

• Geographical Data in Early Puranas, 1972, Dr M. R. Singh

• Ancient Kamboja, People and the Country, 1981, Dr J. L. Kamboj

• Kambojas Through the Ages, 2005, S Kipal Singh

• India and Central Asia, 1955, Dr P. C. Bagchi

• Geography of Puranas, 1973, Dr S. M. Ali

• Greeks in Bactria and India, Dr W. W. Tarn

• Early History of North India, Dr S. Chattopadhyava

• Sakas in Ancient India, Dr S. Chattopadhyava

• Development of Kharoshthi script, C. C. Dasgupta

• Ancient India, 1956, Dr R. K. Mukerjee

• India and the World, p 154, Dr Buddha Parkash

• These Kamboj People, 1979, K. S. Dardi

• Ancient India, Vol III, Dr T. L. Shah

• Hellenism in Ancient India, Dr G. N. Banerjee

• Journal of Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol XLIII, Part I, 1884

• Journal of Bihar and Orissa Research Society, Vol XVI, Part III, & IV, 1930

• Manu and Yajnavalkya, Dr K. P. Jayswal

• Anabaseeos Alexanddrou, Arrian

• Geography, by Ptolemy

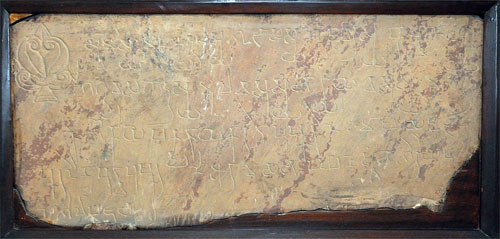

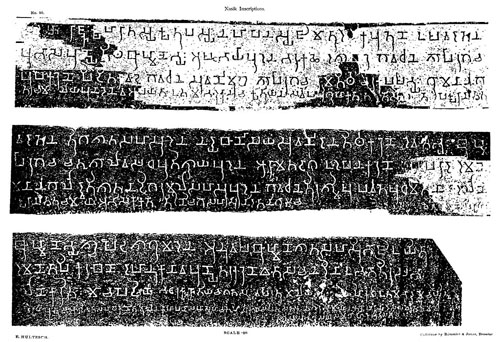

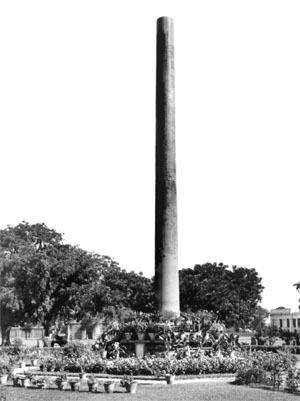

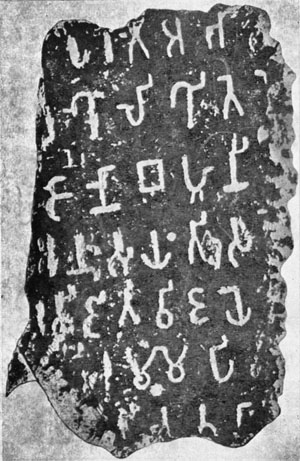

• Mathura Lion Capital Inscriptions

• Corpus Inscriptionium Indicarum, Vol II, Part I, Dr S Konow

See also• Russia

• Siberia

• Ukraine

• Scythians

• Getae

• Massagetaeans

• Thyssagetae

• Goths

• Gutium

• Jutes

• Yuezhi

• Tillia tepe

• Greco-Bactrian Kingdom

• Indo-Greek Kingdom

• Indo-Parthian Kingdom

• Kushan Empire

• Kambojas

• Tarkhan (Punjab)

External links• Y-STR Haplogroup Diversity in the Jat Population Reveals Several Different Ancient Origins David G. Mahal and Ianis G. Matsoukas

• Ancestral Scythian migration of Jatt people (or Jat people)

• "Indo-Scythian dynasties", RC Senior

• Coins of the Indo-Scythians

• Burner relief

• Scythians - Who Were the Scythians

• Scythian Gold From Siberia Said to Predate the Greeks - New York Times | By JOHN VAROLI - Published: January 09, 2002

• Frozen Siberian Mummies Reveal a Lost Civilization | Archaeology | DISCOVER Magazine - by Andrew Curry | From the July 2008 issue; published online June 25, 2008

• The place where Europe began: Spiral cities built on remote Russian plains by swastika-painting Aryans | Mail Online

• Bhim Singh Dahiya: "The Mauryas: Their Identity", Vishveshvaranand Indological Journal, Vol. 17 (1979), p.112-133.

• Origin of the Saka Races - Collapse of the Brahminist Empire (Chapter 3) | by Khshatrapa Gandasa